Back to Journals » Infection and Drug Resistance » Volume 13

Is Echocardiography Mandatory for All Streptococcus gallolyticus Subsp. pasteurianus Bacteremia?

Authors Nasomsong W , Vasikasin V , Traipattanakul J, Changpradub D

Received 2 June 2020

Accepted for publication 9 July 2020

Published 20 July 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 2425—2432

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S265722

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Suresh Antony

Worapong Nasomsong, Vasin Vasikasin, Jantima Traipattanakul, Dhitiwat Changpradub

Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Phramongkutklao Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

Correspondence: Dhitiwat Changpradub

Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Phramongkutklao Hospital and College of Medicine, 317 Ratchavithi Road, Ratchadhevi, Bangkok 10400, Thailand

Tel +6627639337

Email [email protected]

Background: Streptococcus gallolyticus, formerly known as one of the Streptococcus bovis group, is frequently associated with endocarditis. Current guidelines recommended diagnostic work-up for endocarditis among patients with S. gallolyticus bacteremia. However, S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus, was found to be associated with neonatal sepsis and liver diseases and is less commonly associated with endocarditis compared with S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus. Our study aimed to identify the risk factors for S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus endocarditis to help select the patients for echocardiography.

Methods: In this retrospective cohort study, medical records from all adult patients with S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus isolated from blood cultures at Phramongkutklao Hospital from 2009 to 2015 were reviewed. Patients who had mixed bacteremia or missing records were excluded from the study.

Results: During the study period, S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus was isolated among 106 individuals. Mean age was 66.9± 15.6 years. Most patients (61.3%) were male, with cirrhosis as the most common underlying diseases (46.2%), followed by malignancy and chronic kidney disease. Most common manifestations included primary bacteremia (44.3%), followed by spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (23.6%). Infective endocarditis was found among 9 patients. No patients with cirrhosis or single blood specimen of bacteremia had endocarditis (RR 0; p-value 0.003, and RR 1.35; p-value 0.079). The common complications associated with endocarditis were acute respiratory failure (RR 4.32; p-value 0.05), whereas acute kidney injury was a protective factor (RR 0; p-value 0.01). Among 76 patients who had records of 2-year follow-up, no new diagnosis of endocarditis or malignancy was observed.

Conclusion: Among patients with S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus bacteremia, echocardiography might not be needed among patients with cirrhosis and without sustained bacteremia.

Keywords: Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies pasteurianus, endocarditis, cirrhosis, bacteremia

Background

Formerly, Streptococcus bovis was known as a common pathogen for infective endocarditis, usually associated with colorectal neoplasia.1,2 However, taxonomy and nomenclature of S. bovis were distinguished using a molecular method, such as 16s rRNA gene and sodA gene, in six different DNA groups. Common human pathogenic subspecies include S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (formerly S. bovis biotype I), S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus (formerly S. bovis biotype II/2), S. infantarius subsp. infantarius and S. infantarius subsp. coli.2–6

Since the introduction of the new taxonomic classification, the disparity of clinical syndromes and patient’s underlying diseases between the two subspecies were observed. S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus bacteremia was strongly associated with endocarditis and colorectal neoplasia.7,8 Nevertheless, S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus was found to be associated with neonatal sepsis, liver diseases and malignancies of the digestive tract, ie, gastric, pancreatic, hepatobiliary and colorectal cancer and is less commonly associated with endocarditis (14–23%) compared with S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (50–53%).9–15 Nevertheless, many guidelines still recommend diagnostic work-up for endocarditis in all S. gallolyticus bacteremia cases, which may result in unnecessary procedures and higher costs of hospitalization.16,17

Because of the lack of large-scale studies investigating the association between S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus and endocarditis, we aimed to find the risk factors for S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus endocarditis to help select appropriate patients for echocardiography, expected to minimize the unnecessary investigation.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to determine the risk factors for developing endocarditis among patients with S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus bacteremia and secondary objective was to determine the 30-day mortality rate of S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus bacteremia.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted. We collected all blood isolates of S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus obtained from patients from April 2009 to May 2015 at Phramongkutklao Hospital, a 1200 bed teaching hospital of Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Royal Thai Army, Bangkok, Thailand. The inclusion criteria were participants aged over 18 years with monomicrobial S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus bacteremia. Participants referred to other hospitals within the first seven days were excluded. Demographic data, patient characteristics, comorbidities, immunosuppressive status, microbiological data and patient outcomes were recorded. The site of infection was defined according to definitions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.18 Patients whose foci of infection were unidentified were classified as primary bacteremia. Results from echocardiography, ultrasonography, computed tomography and endoscopic examinations searching for endocarditis, hepatobiliary pathology and colonic lesions were collected. All-cause-30-day crude mortality after the onset of bacteremia was recorded. Participants’ medical records were followed up to two years focusing on the finding of new malignancy or endocarditis. The study protocol followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, Royal Thai army Department.

Microbiological Analysis

Bacterial isolates were collected by the clinical microbiological laboratory at the study hospital. Species were identified using the BACTEC system (Becton Dickson, Sparks, MD). The VITEK 2 automated system (bio-Merieux, Hazelwood, MO) was used to identify bacterial species and subspecies. Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined using the disk diffusion test of various antimicrobial agents including penicillin, gentamicin, clindamycin, ceftriaxone, erythromycin, azithromycin, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, tigecycline, linezolid, daptomycin and vancomycin. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the isolates to penicillin and ceftriaxone were performed using the E-test. Disk diffusion and MICs were interpreted using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines.19

Statistical Analysis

For categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test and the Chi-square test were used. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables. For all analyses, a two-sided p-value of 0.05 was considered significant. Potentially significant predictors in the univariate analyses (p- value <0.10) were included in a forward, stepwise multiple logistic regression model to identify the most important factors related to developing endocarditis. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 Software (StataCorp, USA).

Results

During the study period, S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus was isolated in 106 individuals, in whom 191 specimens (88%) blood culture specimens were positive among the overall of 217 specimens taken. The mean age was 66.9±15.6 years. Most patients were male (61.3%), with cirrhosis as the most common underlying disease, followed by diabetes mellitus, malignancy, and chronic kidney disease. Nearly 20% of participants had experienced a malignancy before bacteremic episodes. The most common malignancies included hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer and hematologic malignancy. The most common clinical manifestations comprised primary bacteremia, followed by spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and endocarditis. Acute kidney injury, septic shock, and respiratory failure were the three most common complications. Almost all participants had bacteria isolated in two blood culture specimens. The 30-day crude mortality rate was 21.7%, and baseline characteristics of all participants are shown in the Table 1.

|

Table 1 Baseline Characteristics of All S. gallolyticus Subsp. pasteurianus Bacteremic Participants |

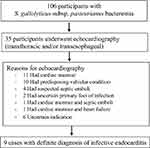

Thirty-five patients underwent echocardiography based on clinical presentation and physician decision as Figure 1. Nine patients were diagnosed with infective endocarditis as described in Table 2. All of whom had positive blood culture in more than two specimens (RR 1.35; p-value 0.079). None of the cirrhosis patients had endocarditis (RR 0; p-value 0.003). The common complication associated with endocarditis was acute respiratory failure (RR 4.32; p-value 0.05), whereas acute kidney injury served as a protective factor (RR 0; p-value 0.01) as shown in Table 3. Because of the small number of patients with endocarditis, multivariate analysis was not performed.

|

Figure 1 Patients underwent echocardiography. |

|

Table 2 Characteristics of Nine Patients with Endocarditis |

|

Table 3 Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Infective Endocarditis in S. gallolyticus Subsp. pasteurianus Bacteremia |

Among 76 patients with records of two-year follow-up, no new diagnosis of endocarditis or malignancy was observed.

The majority of S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus was susceptible to antimicrobial agents, with penicillin susceptibility at 97%. However, a high rate of erythromycin resistance (24.5%) was observed as shown in the Table 4.

|

Table 4 Susceptibility Data of 106 Isolates of S. gallolyticus Subsp. pasteurianus |

Discussion

In this cohort study, nearly one half of the patients with S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus bacteremia presented cirrhosis. This finding was consistent with those of related studies reporting that 15 to 39% of patients had liver diseases or cirrhosis.8,14,15

Regarding the clinical presentations, this study was consistent with others reporting primary bacteremia as the most common clinical presentation, followed by spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and infective endocarditis.8,14,15 About 20% of participants were diagnosed with malignancy before the onset of bacteremia. As in other studies, a correlation between gastrointestinal and other organ malignancies with the bacteremia could not be demonstrated.14 Although colonoscopy was performed in only 10% of patients, which might have underestimated the true prevalence of precancerous colorectal lesions, no new malignancy was observed after two years among 76 participants.

With the proportion of 8.5%, endocarditis was still an uncommon finding, similar to what had been reported in related studies.8,14 None of the endocarditis patients had cirrhosis, which was demonstrated to be a significantly protective factor. The different clinical syndromes between cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients may be explained by the distinction pathophysiology, host-microbe interaction and bacterial virulence factors. Although, no study to date have compared the adherence potential of S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus and S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus to endothelial cells. The surface adhesins such as pili - and in particular the pilus Pil1- is absent from the S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus sequenced strain, and that this pilus plays a major role in infective endocarditis.20 In addition, the adhesin located at the top of the pilus Pil1 is also able to manipulate the host coagulation system which can further promote endocarditis21 accompanied with the expression of blood group antigen sialyl lewis-X (sLex) on human leukocytes increases the adhesion ability of S. gallolyticus to endothelial cells.22–24 In contrast, the main origin of bacteremia among patients with cirrhosis arise from the fecal microbiome, which might have inferior virulence and less adhesion ability to the endothelium.25

Because S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus, isolated from two or more different blood cultures, is one of the two major Duke criteria raising the suspicion of endocarditis, echocardiography should be performed.16,17 From our findings, because of the lower incidence of endocarditis other than S. bovis, this diagnostic procedure might not be needed in patients with cirrhosis, which will decrease the excessive investigation by one half of patients with the bacteremia.

The mortality rate of the bacteremia was higher than related reports.8,14 This observation may be explained by the higher proportion of patients with cirrhosis, which usually had higher complications and mortality rates.25

Although some isolates were intermediate or resistant to beta-lactams using disk diffusion tests, all isolates were susceptible after the MIC measurement when E-test method was performed. This error is due to the poor discrimination ability of disc diffusion tests between penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-intermediate streptococcal populations.26,27 As a result, MIC measurement should be primarily used to interpret susceptibility results or to confirm resistance in resistant isolates determined by the disk diffusion method.

Although this is the first study to demonstrate a correlation between S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus and infective endocarditis among noncirrhotic patients, it had certain limitations. First, although a large number of participants were enrolled in this study, only 8.5% presented endocarditis, which might have overestimated the true association. This small proportion helps confirm that, unlike S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus, S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus uncommonly causes endocarditis. Second, the ability of species identification using VITEK 2 system to discriminate between the two subspecies of S. gallolyticus is not apparent. Nevertheless, studies comparing between the Vitek 2, conventional biochemistry test and molecular testing methods (sodA sequencing, pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA gene) showed generally acceptable agreement.28–30 Finally, due to the retrospective design, factors influencing the physician’s reason for the decision to perform colonoscopy and echocardiography was unidentified, which might have underestimated the prevalence of endocarditis and cancer. However, this bias was minimized by the long-term follow-up.

Conclusion

Among patients with S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus bacteremia, echocardiography might not be needed among patients with cirrhosis and without sustained bacteremia.

Abbreviations

S. bovis, Streptococcus bovis; S. gallolyticus, Streptococcus gallolyticus; S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus, S. gallolyticus subspecies gallolyticus; S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus, S. gallolyticus subspecies pasteurianus; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentrations; CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study protocol followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, Royal Thai army Department.

The Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board, Royal Thai army Department waived the need to obtain consent for the collection, analysis and publication of the retrospectively obtained and anonymized data for this non-interventional study.

Author Contributions

WN prepared proposal, collected the patient data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript.

VV analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding to factors related to developing endocarditis in S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus bacteremia.

J T assisted in patient data collection.

DC supervised the manuscript writing and managed the funding.

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

References

1. Sharara AI, Abou Hamdan T, Malli A, et al. Association of Streptococcus bovis endocarditis and advanced colorectal neoplasia: a case-control study. J Dig Dis. 2013;14(7):382–387. doi:10.1111/1751-2980.12059

2. L S, Collins MD, Re´gnault B, Grimont PA, Bouvet A. Streptococcus infantarius, Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius and Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli isolated from humans and food. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1425–1434. doi:10.1099/00207713-50-4-1425

3. Facklam RR. Recognition of group D streptococcal species of human origin by biochemical and physiological tests. Appl Microbiol. 1972;23:1131–1139. doi:10.1128/AEM.23.6.1131-1139.1972

4. Farrow JAE, Kruze J, Phillips BA, Bramley AJ, Collins MD. Taxonomic studies on Streptococcus bovis and Streptococcus equinus: description of Streptococcus galactolyticus and Streptococcus saccharolyticus. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1984;5:467–482. doi:10.1016/S0723-2020(84)80004-1

5. Osawa R, Fujisawa T, Sly LI. Streptococcus gallolyticus sp. gallate degrading organisms formerly assigned to Streptococcus bovis. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:74–78. doi:10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80451-0

6. Beck M, Frodl R, Funke G. Comprehensive study of strains previously designated Streptococcus bovis consecutively isolated from human blood cultures and emended description of Streptococcus gallolyticus and Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2966–2972. doi:10.1128/JCM.00078-08

7. Boleij A, van Gelder MM, Swinkels DW, Tjalsma H. Clinical importance of Streptococcus gallolyticus infection among colorectal cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(9):870–878. doi:10.1093/cid/cir609

8. Lazarovitch T, Shango M, Levine M, Brusovansky R, Akins R, Hayakawa K. The relationship between the new taxonomy of Streptococcus bovis and its clonality to colon cancer, endocarditis, and biliary disease. Infection. 2013;41:329–337. doi:10.1007/s15010-012-0314-x

9. Biarc J, Nguyen IS, Pini A, et al. Carcinogenic properties of proteins with pro-inflammatory activity from Streptococcus infantarius (formerly S. bovis). Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1477–1484. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgh091

10. Corredoira J, Alonso MP, García-Garrote F, et al. Streptococcus bovis group and biliary tract infections: an analysis of 51cases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:405–409. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12333

11. McCoy WC. Enterococcal endocarditis associated with carcinoma of the sigmoid: report of a case. J Med Assoc State Ala. 1951;21:162–166.

12. Nopjaroonsri P, Leelaporn A, Chayakulkeeree M Clinical characteristics of group D Streptococcal bacteremia in Siriraj Hospital. In:

13. Romero B, Morosini MI, Loza E, et al. Reidentification of Streptococcus bovis isolates causing bacteremia according to the new taxonomy criteria: still an issue. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(9):3228–3233. doi:10.1128/JCM.00524-11

14. Sheng WH, Chuang YC, Teng LJ, Hsueh PR. Bacteraemia due to Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies pasteurianus is associated with digestive tract malignancies and resistance to macrolides and clindamycin. J Infect. 2014;69(2):145–153. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2014.03.010

15. Tripodi MF, Ragone E, Durante Mangoni E, et al. Streptococcus bovis endocarditis and its association with chronic liver disease: an underestimated risk factor. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(10):1394–1400. doi:10.1086/392503

16. Baddour LM, Bayer AS, Fowler VG, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association. Circulation. 2015;132(15):1435–1486. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296

17. Habib G, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European association of nuclear medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;21(44):3075–3128.

18. Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, Horan TC, Hughes JM. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16(3):128e40. doi:10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3

19. Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 20th Informational supplement. CLSI document M100-MS20. [Internet] 2012. Available from: https://clsi.org.

20. Danne C, Entenza JM, Mallet A, et al. Molecular characterization of a Streptococcus gallolyticus genomic island encoding a pilus involved in endocarditis. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(12):1960–1970. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir666

21. Isenring J, Köhler J, Nakata M, et al. Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus endocarditis isolate interferes with coagulation and activates the contact system. Virulence. 2018;9(1):248–261. doi:10.1080/21505594.2017.1393600

22. Jans C, Boleij A. The road to infection: host-microbe interactions defining the pathogenicity of Streptococcus bovis/Streptococcus equinus complex members. Front Microbiol. 2018;10(9):603. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00603

23. Hirota K, Osawa R, Nemoto K, Ono T, Miyake Y. Highly expressed human sialyl Lewis antigen on cell surface of Streptococcus gallolyticus. Lancet. 1996;347:760. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90109-9

24. Vollmer T, Hinse D, Kleesiek K, Dreier J. Interactions between endocarditis-derived Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus isolates and human endothelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:78. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-10-78

25. Bunchorntavakul C, Chamroonkul N, Chavalitdhamrong D. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: a critical review and practical guidance. World J Hepatol. 2016;8(6):307–321. doi:10.4254/wjh.v8.i6.307

26. National committee for clinical laboratory standards performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Fifteenth information supplement M100-S15. NCCLS [Internet] 2005. Available from: https://clsi.org/.

27. Streit JM, Steenbergen JN, Thorne GM, Alder J, Jones RN. Daptomycin tested against 915 bloodstream isolates of viridans group streptococci (eight species) and Streptococcus bovis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55(4):574–578. doi:10.1093/jac/dki032

28. Dekker JP, Lau AF. An update on the Streptococcus bovis group: classification, identification, and disease associations. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(7):1694–1699. doi:10.1128/JCM.02977-15

29. Funke G, Funke-Kissling P. Performance of the new VITEK 2 GP card for identification of medically relevant gram-positive cocci in a routine clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(1):84–88. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.1.84-88.2005

30. Haanperä M, Jalava J, Huovinen P, Meurman O, Rantakokko-Jalava K. Identification of alpha-hemolytic streptococci by pyrosequencing the 16S rRNA gene and by use of VITEK 2. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(3):762–770. doi:10.1128/JCM.01342-06

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.