Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Internet Addiction and Academic Anxiety Among Chinese College Students During COVID-19: The Mediating Role of Psychological Contract

Received 27 July 2023

Accepted for publication 16 September 2023

Published 3 October 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 3949—3962

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S428599

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Shengchen Chen,1 Weihua Wang2

1School of Business Administration, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, South Korea; 2School of Business Administration, Anhui University of Finance and Economics, Bengbu, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Weihua Wang, School of Business Administration, Anhui University of Finance and Economics, Bengbu, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86-552-3171001, Fax +86-552-3175978, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The objective of this study is to investigate the underlying mechanism connecting internet addiction and academic anxiety, with the aim of assisting higher education professionals and administrators in developing comprehensive solutions to effectively mitigate the systemic risks associated with these issues.

Patients and Methods: This study utilizes the smart data collection instrument of Wenjuanxing to gather data from 270 Chinese college students through an online questionnaire survey. Through building and analyzing a structural equation model that consists of four latent variables, such as internet addiction, relational psychological contract, transactional psychological contract, and academic anxiety. The study analyzed the fundamental characteristics of the transformation mechanism of Internet addiction and academic anxiety. It specifically focused on conducting a mediating effects test of the psychological contract variable to validate the significant role of both relational psychological contract and transactional psychological contract in this transformation mechanism.

Results: First, the study found that internet addiction (β=0.094; p=0.179) cannot directly impact academic anxiety. It can only influence academic anxiety through the mediating effects of the relational psychological contract (β=0.088; p=0.022) and the transactional psychological contract (β=0.123; p=0.003), with the latter having a more significant impact. Second, the destructive effect of Internet addiction on relational psychological contracts (β=− 0.496; p< 0.001) is greater than that on transactional psychological contracts (β=− 0.476; p< 0.001). Third, compared to the weakening of the relational psychological contract (β=− 0.177; p=0.017), the weakening of the transactional psychological contract (β=− 0.258; p=0.001) has a more significant impact on college students’ academic anxiety.

Conclusion: This study shows that the weakening of the corresponding psychological contract is the key link for the development of Internet addiction into academic anxiety. Stabilizing the psychological contracts at the psychological level of college students can help suppress the vicious transformation process from internet addiction to academic anxiety, ensuring students’ mental health and reducing systemic risks in educational work.

Keywords: internet addiction, academic anxiety, customer satisfaction, relational psychological contract, transactional psychological contract

Introduction

For a considerable period of time, the intertwined relationship between internet addiction and academic anxiety has been closely linked to various detrimental behaviors and negative outcomes.1–4 These consequences include reduced engagement in learning,1 ineffective time management,3 academic underperformance,2 heightened stress levels,2 and even the development of certain mental disorders.5,6 Consequently, the risks associated with educational endeavors have witnessed a significant escalation.3,7 Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of online learning,8 especially within higher education institutions in China.9,10 This shift has placed a greater reliance on the internet for academic activities,11 thereby exacerbating the problem of internet addiction and compounding the issue of academic anxiety.8,9 Consequently, there exists an immediate imperative to undertake a comprehensive and systematic study aimed at addressing these two challenges. The concerns surrounding these issues are particularly prominent among professionals in higher education, who are actively seeking solutions while mitigating associated risks.6,8,9

However, previous studies have predominantly treated internet addiction and academic anxiety as separate phenomena.12–14 These studies primarily focused on identifying,12,13 measuring,13,14 and describing specific aspects of each issue,14 without fully exploring their potential correlations. Consequently, the interconnections between these two problems have largely been overlooked. Although these studies have provided valuable insights,12–14 they have not made significant contributions to addressing the systemic risks associated with internet addiction and academic anxiety, impeding the development of comprehensive strategies to effectively manage them.

To bridge this gap, the present study aims to investigate the underlying mechanism behind the transition from internet addiction to academic anxiety. Its primary objective is to aid higher education professionals and administrators in devising comprehensive solutions that effectively manage the systemic risks associated with these issues and promote the academic success of college students. To achieve this objective, the study focuses on examining the mediating effect of the psychological contract between students and their schools. The psychological contract, recognized as a classic measure of relationship closeness between employees and organizations,15–18 can also serve as an effective indicator of the intangible relationship quality between students and schools.19–21 Furthermore, it is closely linked to individual psychological changes and behavioral tendencies in students.21,22 Drawing upon the psychological contract theory,15,23,24 the study proposes a theoretical framework with corresponding hypotheses. This framework incorporates internet addiction as the independent variable and academic anxiety as the dependent variable, thereby establishing a model of psychological mechanisms. The explanatory power of this model is validated through data analysis conducted on Chinese college students. Based on the findings, the study further engages in an in-depth discussion and provides recommendations.

Through the undertaking of this study, the proposed model of psychological mechanisms aims to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the transition from internet addiction to academic anxiety. The findings hold the potential to be particularly relevant to risk management in the field of education, offering practical insights and guidance for the development of comprehensive strategies that enhance college students’ mental health and academic success.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Psychological contract theory has been widely used in management and organization studies literature,16,18,25 but the use of this theory in the context of higher education is much sparser.22 In light of this, the present study aims to bridge this gap by establishing a theoretical framework that specifically delves into the formation and influence processes of the psychological contract within educational settings. The primary objective is to verify the applicability of this theory in the context of higher education. By doing so, the study seeks to shed light on the dynamics of the psychological contract and its potential impact on the relationship between internet addiction and academic anxiety. Existing research suggests that internet addiction can lead individuals to become overly reliant on the virtual online environment,3,14,26 resulting in a sense of disconnection from real-life experiences.3,27,28 Specifically for college students, as internet addiction intensifies, individuals may become psychologically detached from their real-life and learning environments.6,29 Consequently, this detachment weakens the psychological contract between college students and their affiliated organizations (universities), eroding their sense of belonging, achievement, and confidence in the long-term benefits from these organizations.30 As a result, it can lead to varying degrees of academic anxiety. In this chapter, the study focuses on exploring the potential connections between the following concepts, aiming to initiate a comprehensive and systematic discussion of the problem.

Internet Addiction

In recent years, the rapid development of technology has led to the pervasive use of the internet, making it an indispensable part of modern life.12,14,27 While the internet has undoubtedly brought numerous benefits, it has also given rise to a concerning phenomenon known as internet addiction.12 Internet addiction refers to an excessive and compulsive use of the internet that interferes with daily activities and negatively impacts various aspects of an individual’s life,12,29 including their academic performance,29 social interactions,3,27 12 and mental health.3,27,31,32 Among the various groups affected by internet addiction, college students are particularly vulnerable.6,27 With easy access to the internet and the increasing reliance on digital platforms for academic and social purposes,33 college students often find themselves spending excessive amounts of time online, engaging in activities such as gaming, social media, and online shopping,14 which have a number of negative effects on their studies and personal lives.6,34

This study argues that one of the most significant negative impacts of internet addiction on students is the manifestation of academic anxiety.3,27 As students become increasingly engrossed in their online activities, they may neglect their academic responsibilities,35 leading to poor time management, decreased concentration, and a decline in overall academic performance.27,29 Moreover, the constant distractions and instant gratification provided by the internet can impair students’ ability to focus and engage in effective studying, further exacerbating their academic anxiety.3,29 The pressure to meet academic expectations combined with the addictive nature of the internet can create a vicious cycle, where increased anxiety leads to increased internet use, perpetuating the problem.3 Particularly in the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic, college students are forced to rely more on the internet to fulfill their academic requirements, exacerbating the aforementioned issues.34,36 In view of this, it is the focus of this paper to discuss the potential linkage mechanism of these two problems, and the core of this linkage mechanism is psychological contract.

Psychological Contract

Psychological contract is a common topic in organizational psychology and a key link between internet addiction and academic anxiety in the framework of this study. In previous research, the concept of psychological contracts has gained significant attention as it pertains to the mutual expectations and obligations between individuals and the organizations to which they belong.16,18,37 Psychological contracts are characterized by the unwritten, implicit agreements that exist between individuals and the organization, encompassing reciprocal expectations, obligations, and perceived fairness in the employment relationship.37–39 When examining the context of higher education, college students also develop their own psychological contracts with their educational institutions.21,22 These psychological contracts can be classified into two main categories: relational psychological contracts and transactional psychological contracts. While the former emphasizes implicit, trust-based expectations and social factors,18,38,39 it represents the students’ commitment and recognition of the stable relationship between themselves and the school. The latter focuses on explicit, exchange-based obligations and tangible rewards,38–40 which means that students expect to receive benefits from the school.

The transactional psychological contract elucidates the explicit expectations and obligations between individuals and their affiliated organization.37,38 Grounded in an social exchange theory perspective,18,39,41 the transactional psychological contract centers on the notion of a quid pro quo relationship where organizational members contribute their skills, time, and effort in exchange for tangible rewards and invisible benefits, such as job security.37 It encompasses the formal agreements, policies, and explicit obligations outlined in employment contracts, job descriptions, and performance expectations. This conceptualization clarifies the transactional nature of the contractual relationship between individuals and organizations, emphasizing the stability of this implicit contract based on explicit benefits.24,38 Employees expect fair treatment, equitable compensation, and adherence to agreed-upon terms.37 Similarly, students expect certain explicit gains or rewards, such as grades, certifications, and improved employability. The transactional psychological contract highlights the importance of clarity, communication, and the fulfillment of contractual obligations to maintain organizational member satisfaction, trust, and commitment.23,37 Moreover, it underscores the significance of organizational justice and the fulfillment of promised rewards in shaping organizational members’ perceptions of the psychological contract.15,18

Unlike the transactional psychological contract, which focuses on explicit and tangible obligations,23,37 the relational psychological contract places emphasis on the implicit, often unwritten obligations that arise from the employment relationship.19,42 This conceptualization acknowledges the critical role of trust, fairness, and mutual respect in promoting enduring employment relationships.23 The relational psychological contract recognizes that employees form a set of beliefs and expectations about how their investments in their employing organizations will be reciprocated.15 These investments may include loyalty, commitment, and discretionary effort.15,38 Additionally, it acknowledges the influence of social and interpersonal factors, such as supervisor support and coworker relationships, on shaping individuals’ perceptions of their psychological contract.23 In the educational environment, the relational psychological contract focuses on developing long-term, trusting relationships between students and their educational institutions.19,21 This contract emphasizes aspects such as invisible support, mentoring, and opportunities for personal growth. Understanding and managing the relational psychological contract have implications for fostering student satisfaction and creating a conducive learning environment.21,22

However, under the influence of internet addiction, these psychological contracts may undergo changes. Firstly, excessive internet use and addiction can weaken an individual’s sense of belonging to the real world, and thus disrupt the individual-institution trusting relationships.3 In an educational environment, students may have doubts about their ability to maintain a long-term relationship with the school and, as a result, miss out on opportunities for growth.34 This means that internet addiction has a significant destructive effect on relational psychological contracts. As the sense of belonging to the school weakens, students may also decrease their expectations of obtaining relevant resources from the institution.27,29 This implies that internet addiction can significantly impact transactional psychological contracts. Based on this information, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1. Internet addiction has a negative impact on relational psychological contract. H2. Internet addiction has a negative impact on transactional psychological contract.

Understanding the changes in psychological contracts under the influence of internet addiction is crucial for higher education practitioners and policymakers. By recognizing the shifts in these contracts, interventions can be developed to restore a healthy balance and promote holistic student development.

Academic Anxiety

Academic anxiety, characterized by feelings of apprehension, worry, and stress related to academic tasks, evaluations, and achievements,1,2,4 has been recognized as a significant concern in educational risk research,4,7 along with internet addiction.3,6 Among college students, academic anxiety is a prevalent psychological condition that can have profound effects on their academic performance,43 mental health,44 and overall educational experience.3,7 The numerous academic demands faced by students, such as coursework, exams, presentations, and deadlines, along with the high expectations placed upon them, contribute to the development of academic anxiety.1 Consequently, students may exhibit symptoms such as excessive worry, difficulty concentrating, perfectionism, fear of failure, and self-doubt, significantly hindering their ability to perform at their best.45,46

Previous research suggests that the causes of academic anxiety in college students are multifaceted. Factors such as fear of failure, self-imposed high standards, excessive workload, time management challenges, and the competitive academic environment all contribute to the development and exacerbation of academic anxiety.4,7,46 Furthermore, the recent shift to online learning and the disruptive effects of the pandemic have introduced additional stressors,47 such as isolation, lack of face-to-face interaction,9,10 and the resulting deep internet addiction,48,49 which further amplify academic anxiety among college students.46,50 This study aims to illuminate the complex relationship between internet addiction and academic anxiety in college students. The basic premise is to determine whether there is a direct connection between these two variables. Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3. Internet addiction has a significant impact on academic anxiety.

It is worth noting that, against the backdrop of the pandemic, the learning environment for college students has rapidly transitioned to an online setting, often forcing them to leave the campus and engage in academic activities from their homes.9,10 This abrupt shift can have detrimental effects on the psychological contract between students and their educational institutions, specifically within the realm of the relational psychological contract. The corresponding weakening of the psychological contract implies that college students have lower expectations for the long-term relationship between themselves and the school.21,22 Consequently, they may have reduced confidence in receiving invisible support, guidance, and other growth opportunities from the institution. These additional pressures are a significant cause of academic anxiety.51 To test this proposition, the study presents the following hypothesis.

H4. Relational psychological contract has a negative impact on academic anxiety.

Moreover, the weakening of the transactional psychological contract has implications for college students. It undermines their explicit commitments and expectations regarding tangible benefits they anticipate from the educational institution,19 such as academic achievements, graduation credentials, and employability skills.24 When these anticipated benefits are hard to fulfill as expected, it inevitably results in increased psychological pressure and heightened academic anxiety among individual students.1,2 The disparity between what students had hoped to achieve and the actual outcomes creates a sense of disappointment and added stress, negatively impacting their overall well-being and academic performance.4,44 In view of this, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H5. Transactional psychological contract has a negative impact on academic anxiety.

The aforementioned discussion highlights the detrimental impact of internet addiction on the psychological contract between college students and their educational institutions, ultimately leading to the development of academic anxiety. This implies that the psychological contract, as an intangible set of expectations and commitments,37,52 is significantly influenced by behavior characters in the virtual environment,53,54 such as internet addiction. Conversely, it also has a direct influence on behavior characters in the real environment,30,55 such as academic anxiety. Therefore, the psychological contract can be viewed as an important mediating factor between internet addiction and academic anxiety. It serves as a bridge between these two phenomena, demonstrating the intricate relationship between virtual behaviors and real-world consequences. Understanding the role of the psychological contract in this context is essential for comprehending the underlying dynamics and developing strategies to address the adverse effects of internet addiction on students’ well-being and academic performance. In view of this, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H6. Relational psychological contract plays a mediating role in the relationship between internet addiction and academic anxiety. H7. Transactional psychological contract plays a mediating role in the relationship between internet addiction and academic anxiety.

Research Design

Conceptual Model

As depicted in Figure 1, this study utilizes the psychological contract theory to establish a conceptual model that examines the relationships among internet addiction, relational psychological contract, transactional psychological contract, and academic anxiety. In this model, internet addiction is considered the independent variable, academic anxiety as the dependent variable, and relational/transactional psychological contracts as the mediating variables.

|

Figure 1 Conceptual Model and Hypothesis. |

Survey Samples

The study began with a pre-test to establish the validity and reliability of the questionnaire.56 A group of 30 respondents provided feedback on the questionnaire’s wording, relevance, and suggested corrections. Confirmatory factor analysis and Cronbach’s reliability were employed to assess the pre-test results. As a result, one item from the internet addiction and two items from the transactional psychological contract were removed. As presented in Table 1 and Table 2, the final questionnaire comprised 3 demographic questions and 17 concept measurement items. To minimize common method bias and enhance the survey’s reliability, certain measures were implemented. These included using antisense inquiry questions, incorporating temporal and psychological distance when measuring target variables,38 and eliminating ambiguities in item meanings.57,58 This study utilizes the smart data collection instrument of Wenjuanxing to gather data through an online questionnaire survey. The primary data for the survey was collected in September 2022 from students at eleven universities and colleges in China. A total of 292 students participated, and after excluding 22 invalid questionnaires, 270 valid questionnaires were accepted and used for subsequent analysis.

|

Table 1 Measurement Instruments |

|

Table 2 Demographic Description of Sample |

Constructs Measures

Drawing upon prior research, slight modifications were made to the measurement items in order to accommodate the target population.58 Respondents were required to provide responses using a five-level Likert scale, where 5 indicated full approval and 1 represented full disagreement. As illustrated in Table 1, we utilized 7 items to measure internet addiction, 4 items to assess relational psychological contract, 3 items to gauge transactional psychological contract, and 3 items to evaluate academic anxiety.

Sample Description

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are outlined in Table 2. Among the participants, 128 individuals (47.1%) identify as female, while 142 individuals (52.6%) identify as male. The majority of respondents (68.9%) are science majors. The total sample for the survey includes 91 (33.7%) freshmen, 51 (18.9%) sophomores, 67 (24.8%) juniors, and 61 (22.6%) seniors or above.

Data Analyses

Firstly, the SmartPLS 3.3 was used to analyze the collected data for this research, with the aim of evaluating the reliability and validity of the measurements. Moreover, SmartPLS 3.3 utilizes the Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach to enable the simultaneous estimation of both predictive and explanatory models.59 This methodology helps to avoid unacceptable solutions and indeterminate factors.60 Meanwhile, PLS is well-suited for examining complex relationships within the research framework,61,62 as is the case in this study.

Convergent Validity and Reliability

To evaluate these measures, the study utilized composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE), as shown in Table 3. The CR values for all latent variables exceeded 0.70, while the AVE values were above 0.50. This suggests that the variables under consideration account for over 50% of the observed variances in the items.62 Furthermore, the constructs in the model demonstrated high internal consistency and reproducibility, as evidenced by Cronbach’s alpha (CA) coefficients exceeding 0.7 for each variable. Moreover, the factor loadings for all items ranged from 0.723 to 0.870, indicating strong convergent validity. This ensures the convergent validity and reliability of all constructs within the measurement model.57

|

Table 3 Test Results of Internal Reliability and Convergent Validity |

Common Method Bias Test

The study acknowledges the potential presence of common-method variance due to the use of self-reported data.63 To assess the extent of this bias, Harman’s single-factor test, a widely adopted method for addressing common method bias, was conducted. The results revealed that the cumulative extraction sums of squared loadings for the single factor accounted for only 38.8% of the variance. The impact of common method bias is found to be insignificant.

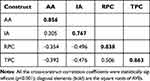

Discriminant Validity of Constructs

This study conducted an analysis to assess the discriminant validity of the measurement constructs. The examination involved calculating the correlations between the constructs and comparing them with the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct. The results, as presented in Table 4, confirm the presence of discriminant validity. Specifically, the square root of the AVE for each construct was found to be greater than the correlation coefficients between that construct and other constructs. This indicates that the measurement constructs are distinct and not highly correlated with each other.47,62 Consequently, the study’s findings support the discriminant validity of the measurement model, indicating that the constructs are measuring unique aspects of the research variables.

|

Table 4 Correlations (Squared Correlations), Reliability, and AVE |

Structural Model Results

The study initially checked the potential collinearity problems in samples, and found that all variance inflation factor (VIF) values were below the threshold of 5.00. This indicates that collinearity did not impact the structural model.64 Additionally, SmartPLS provided the R2 values for each dependent variable.61 The R2 for relational psychological contracts (RPC) was 0.468, explaining 46.8% of the observed variation. For transactional psychological contracts (TPC), the R2 was 0.434, explaining 43.4% of the variation. Lastly, the R2 for academic anxieties (AA) was 0.384, explaining 38.4% of the variation. These findings indicate that the structural model had satisfactory explanatory power.

The PLS algorithm analysis revealed a significant positive path coefficient between internet addiction (IA) and relational psychological contracts (RPC). Additionally, a bootstrapping procedure was employed to further validate the significance of the path coefficient. The results presented in Table 5 display the path coefficient, significance level, p-value, t-value, and the corresponding 95% bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence interval. The direct effect (β=−0.496; p<0.001) was found to be significant, providing support for hypothesis H1. Conversely, hypothesis H2 is rejected. This is because the path coefficient (β=0.094; p=0.179) corresponding to this hypothesis is not significant. Similarly, hypothesis H2, H4 and H5 are supported.

|

Table 5 Effect Coefficient and Hypothesis Testing |

In addition, Table 5 reveals that internet addiction (IA) has a relatively significant indirect effect on academic anxieties (AA) via relational psychological contracts (RPC), Hypothesis H6 is supported. Similarly, hypothesis H7 is supported. In this study, the mediating role of reveals that relational psychological contracts (RPC) and transactional psychological contracts (TPC) is confirmed, and the role of transactional psychological contracts (TPC) (β=0.123; p=0.003) is greater than that of relational psychological contracts (RPC) (β=0.088; p=0.022).

Discussion

On the whole, this study analyzed in detail the mechanism of influence of internet addiction on academic anxiety of college students under the mediation of two different psychological contracts. At the same time, the potential relationship between different variables was explored in depth and the following conclusions were drawn.

Firstly, this study finds that internet addiction has a significant negative impact on the psychological contract between college students and their schools. The results of this study once again verified the destructive effect of internet addiction on the existing relationship between individuals and affiliated organizations in the real environment.3,34 And the psychological mechanism of destruction is further clarified. This study believes that under the background of frequent quarantine, college students’ campus feelings have suffered great damage.34,36 The campus environment, which used to be the social foundation and spiritual sustenance, is easily replaced by the virtual network environment.27,48 This is the inevitable consequence of overusing the internet.26 Because the Internet can provide enough or even excessive social and entertainment resources,3 it is easier to attract the attention of people, especially young people, and become an effective spiritual place for them,6,35 thus weakening their existing ties with the affiliated organizations. This finding should attract the attention of higher education practitioners and relevant researchers, and can be used as the theoretical basis for the formulation of corresponding risk control strategies.

Secondly, this study reveals that internet addiction has a greater impact on relational psychological contracts than on transactional psychological contracts. The findings indicate that individuals’ expectations and commitments of establishing a stable relationship with the organization are more susceptible to the influence of internet addiction compared to their psychological expectations of long-term benefits derived from organizational affiliation. It can be argued that, within the context of the pandemic, the detrimental effects of internet addiction on the psychological contract between college students and their school primarily manifest as a weakening of expectations for a long-term relationship, rather than expectations of benefits derived from this relationship. To a certain extent, this also illustrates that agreements based on self-interest exchange between individuals and their affiliated organizations are more stable and less susceptible to external factors.24,38 Even though these unwritten, implicit agreements are only manifested at the psychological level.37–39 This conclusion not only reaffirms the stability of the social exchange relationship as found in previous research,38,41 but it also makes a significant contribution to the comparative study of different psychological contracts.

Thirdly, the research findings indicate that both relational and transactional psychological contracts have a significant negative impact on academic anxiety. Notably, the impact of transactional psychological contracts exceeds that of relational psychological contracts by a significant margin. This indicates that a breakdown in a secure psychological connection with the educational institution can lead to academic anxiety.4 But the feelings of disillusionment and a sense of loss, stemming from the perception that the promised long-term benefits of attending school are not being realized,4,44 have a more significant impact on college students’ academic anxiety.1 These factors are the primary catalysts behind the heightened levels of anxiety experienced by students. In contrast, students’ long-term expectations and commitments of their relationship with the school have only a lesser impact. This result, once again, reinforces the significance of transactional psychological contracts based on long-term interests from the opposite perspective, as compared to the second conclusion above.

Finally, this study confirms two pathways that link Internet addiction and academic anxiety by analyzing the mediating role of the psychological contract. The findings indicate that internet addiction cannot directly impact academic anxiety. Instead, it can only influence academic anxiety through the mediating effects of the relational psychological contract and the transactional psychological contract, with the latter having a more significant impact. The findings provide a summary for the discussion of the potential relationship between Internet addiction and academic anxiety in previous studies.3,4 It can be argued that internet addiction can worsen academic anxiety by diminishing students’ commitment to individual-school relationships and their expectations of benefits from school. Ultimately, this can have a negative impact on their mental health and academic performance.6,34 In this process, the weakening of the expectation of shared interests plays a more important intermediary role. This finding not only systematically elucidates the mechanism connecting internet addiction and academic anxiety but also provides a theoretical breakthrough for effectively preventing the transition from internet addiction to academic anxiety.

Research Implications

From a theoretical standpoint, this study presents a model that establishes a mechanism for the psychological transformation from internet addiction to academic anxiety, with the psychological contract as the central component. This model aims to provide a more comprehensive and systematic understanding of how internet addiction influences the experience of academic anxiety among college students. It helps to delve deeper into the potential characteristics of internet addiction and academic anxiety. In contrast to traditional studies that examine these two issues in isolation,12–14 this study highlights their correlation, allowing for a better understanding of the systemic risk associated with them,3,7 particularly in the context of the epidemic. Furthermore, this research expands the application of psychological contract theory and offers novel perspectives on resolving inherent issues within the field of higher education by confirming the mediating role of the psychological contract.

In terms of practical management, this study clarifies two distinct paths through which internet addiction influences academic anxiety and outlined a complete framework of psychological contract. These findings provide a deeper understanding of the negative impact of internet addiction and certain factors contributing to academic anxiety among college students. Meanwhile, they are also helpful for higher education practitioners to comprehensively monitor the potential link between internet addiction and academic anxiety, enhancing their ability to manage related systemic risks. Particularly, considering the key role emphasized in the research results regarding two types of psychological contracts, relevant decision makers should use them as a starting point to implement effective intervention measures. Stabilizing the implicit psychological contracts at the psychological level of college students can help suppress the vicious transformation process from internet addiction to academic anxiety,3 ensuring students’ mental health, and reducing systemic risks in educational work.

Limitations and Further Research

Although this study has yielded meaningful results, there are certain limitations that need to be addressed in future research. Firstly, the data used in this study were collected solely during the period of the epidemic, lacking a comparison with data from non-epidemic environments. Consequently, there are unknown limitations in the corresponding analytical results. Secondly, the survey target of this study was focused on students from Chinese universities, lacking support from sample data from other regions, which restricts the generalizability of the conclusions. In light of this, our future research could involve exploring potential cultural variations in the relationship between internet addiction, psychological contracts, and academic anxiety by including samples from diverse geographical regions. Additionally, expanding the study to consider other demographic factors, such as socioeconomic backgrounds or academic performance, might provide further insights into the intricate interplay of these variables.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the School of Business Administration, Anhui University of Finance and Economics, Bengbu, Anhui Province, China. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants followed the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Respondents’ participation was completely consensual, anonymous, and voluntary.

Funding

This study was supported by the Innovation Fund of Anhui Province (Grant No. 2019LCX025).

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1. Macher D, Paechter M, Papousek I, Ruggeri K. Statistics anxiety, trait anxiety, learning behavior, and academic performance. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2012;27(4):483–498. doi:10.1007/s10212-011-0090-5

2. Soares S, Boyes ME, Parrila R, Badcock NA. Does reading anxiety impact on academic achievement in higher education students? Dyslexia. 2023;29(3):179–198. doi:10.1002/dys.1738

3. Olawade DB, Olorunfemi OJ, Wada OZ, Afolalu TD, Enahoro MA. Internet addiction among university students during COVID-19 lockdown: case study of institutions in Nigeria. J Educ Hum Dev. 2020;9(4):165–173. doi:10.15640/jehd.v9n4a17

4. Cassady JC. Anxiety in Schools: The Causes, Consequences, and Solutions for Academic Anxieties. Vol. 2. Peter Lang; 2010.

5. Nail JE, Christofferson J, Ginsburg GS, et al. Academic impairment and impact of treatments among youth with anxiety disorders. Child Youth Care Forum. 2015;44(3):327–342. doi:10.1007/s10566-014-9290-x

6. Kurt DG. Suicide risk in college students: the effects of internet addiction and drug use. Educ Sci Theory Pract. 2015;15(4):841–848.

7. Hasty LM, Malanchini M, Shakeshaft N, Schofield K, Malanchini M, Wang Z. When anxiety becomes my propeller: mental toughness moderates the relation between academic anxiety and academic avoidance. Br J Educ Psychol. 2021;91(1):368–390.

8. Al-Nasa’h M, Al-Tarawneh L, Abu Awwad FM, Ahmad I. Estimating students’ online learning satisfaction during COVID-19: a discriminant analysis. Heliyon. 2021;7(12):e08544.

9. Guo C, Wan B. The digital divide in online learning in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technol Soc. 2022;71:102122.

10. He W, Zhao L, Su YS. Effects of online self-regulated learning on learning ineffectiveness in the context of COVID-19. Int Rev Open Dis. 2022;23(2):25–43. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v23i2.5775

11. Jackson KM, Szombathelyi MK. Holistic Online Learning, in a Post COVID-19 World. Acta Polytech. 2022;19(11):125–144. doi:10.12700/APH.19.11.2022.11.7

12. Weinstein A, Lejoyeux M. Internet addiction or excessive internet use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):277–283. doi:10.3109/00952990.2010.491880

13. Kuss DJ, Shorter GW, van Rooij AJ, Griffiths MD, Schoenmakers TM. Assessing internet addiction using the parsimonious internet addiction components model-a preliminary study. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2014;12(3):351–366.

14. Prochazka R, Sucha J, Dostal D, et al. Internet addiction among Czech adolescents. Psych J. 2021;10(5):679–687. doi:10.1002/pchj.454

15. Zhang LA, Zeng QY, Yang L, Han Y, Xu YX. Can psychological contracts decrease opportunistic behaviors? Front Psychol. 2022;13:911389.

16. Braganza A, Chen W, Canhoto A, Sap S. Productive employment and decent work: the impact of AI adoption on psychological contracts, job engagement and employee trust. J Bus Res. 2021;131:485–494. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.018

17. Gresse WG, Linde BJ. The anticipatory psychological contract of management graduates: validating a psychological contract expectations questionnaire. S Afr J Econ Manag Sci. 2020;23(1). doi:10.4102/sajems.v23i1.3285

18. Topa G, Aranda-Carmena M, De-Maria B. Psychological contract breach and outcomes: a systematic review of reviews. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15527. doi:10.3390/ijerph192315527

19. Itzkovich Y. Constructing and validating students’ psychological contract violation scale. Front Psychol. 2021;12:685468. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.685468

20. Spies AR, Wilkin NE, Bentley JP, Bouldin AS, Wilson MC, Holmes ER. Instrument to measure psychological contract violation in pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(6):107. doi:10.5688/aj7406107

21. Bordia S, Bordia P, Milkovitz M, Shen Y, Restubog SLD. What do international students really want? An exploration of the content of international students’ psychological contract in business education. Stud High Educ. 2019;44(8):1488–1502. doi:10.1080/03075079.2018.1450853

22. O’Toole P, Prince N. The psychological contract of science students: social exchange with universities and university staff from the students’ perspective. High Educ Res Dev. 2015;34(1):160–172. doi:10.1080/07294360.2014.934326

23. Kutaula S, Gillani A, Budhwar PS. An analysis of employment relationships in Asia using psychological contract theory: a review and research agenda. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2020;30(4):100707. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100707

24. Koskina A. What does the student psychological contract mean? Evidence from a UK business school. Stud High Educ. 2013;38(7):1020–1036. doi:10.1080/03075079.2011.618945

25. Liu M, Liu X, Muskat B, Leung XY, Liu SS, Employees’ self-esteem in psychological contract: workplace ostracism and counterproductive behavior. Tour Rev. 2023. doi:10.1108/TR-11-2022-0535

26. Zhao M, Huang YL, Wang JY, Feng J, Zhou B. Internet addiction and depression among Chinese adolescents: anxiety as a mediator and social support as a moderator. Psychol Health Med. 2023;28(8):2315–2328. doi:10.1080/13548506.2023.2224041

27. Qian D, Yongxin Z, Hua W, Wei H. Zhongyong thinking style and internet addiction of college students: serial mediating effect of social support and loneliness. Studi Psychol Behavior. 2019;17(4):553.

28. Qin Y, Liu SJ, Xu XL. The causalities between learning burnout and internet addiction risk: a moderated-mediation model. Soc Psychol Educ. 2023. doi:10.1007/s11218-023-09799-7

29. Lin YJ, Hsiao RC, Liu TL, Yen CF. Bidirectional relationships of psychiatric symptoms with internet addiction in college students: a prospective study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119(6):1093–1100. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2019.10.006

30. Dai WJ, Kaifa Z. An analysis of students’ work values education strategies and environment based on psychological contract. J Environ Public Health. 2022;2022:1–9. doi:10.1155/2022/4798768

31. Zhou R, Xiao XY, Huang WJ, et al. Video game addiction in psychiatric adolescent population: a hospital-based study on the role of individualism from South China. Brain Behav. 2023;13(9). doi:10.1002/brb3.3119.

32. Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Online social networking and addiction-a review of the psychological literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(9):3528–3552. doi:10.3390/ijerph8093528

33. Roberts JA, Yaya LHP, Manolis C. The invisible addiction: cell-phone activities and addiction among male and female college students. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(4):254–265. doi:10.1556/JBA.3.2014.015

34. Shehata WM, Abdeldaim DE. Internet addiction among medical and non-medical students during COVID-19 pandemic, Tanta University, Egypt. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28(42):59945–59952. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-14961-9

35. Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Binder JF. Internet addiction in students: prevalence and risk factors. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(3):959–966. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.024

36. Chang BR, Hou JH. The association between perceived risk of COVID-19, psychological distress, and internet addiction in college students: an application of stress process model. Front Psychol. 2022;13:898203.

37. Rousseau D. Psychological Contracts in Organizations: Understanding Written and Unwritten Agreements. Sage publications; 1995.

38. Liu W, Chen X, Lu X, Fan X. Exploring the relationship between users’ psychological contracts and their knowledge contribution in online health communities. Front Psychol. 2021;12:612030. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.612030

39. Rousseau DM. New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: a study of psychological contracts. J Organ Behav. 1990;11(5):389–400. doi:10.1002/job.4030110506

40. Hui Z. Corporate social responsibilities, psychological contracts and employee turnover intention of SMEs in China. Front Psychol. 2021;12:754183.

41. Foa EB, Foa UG. Resource theory of social exchange. In: Handbook of Social Resource Theory. Springer; 2012:15–32.

42. Bi QQ. Cultivating loyal customers through online customer communities: a psychological contract perspective. J Bus Res. 2019;103:34–44. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.005

43. Zeng Y, Zhang J, Wei J, Li S. The impact of undergraduates’ social isolation on smartphone addiction: the roles of academic anxiety and social media use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15903. doi:10.3390/ijerph192315903

44. Jia J, Wang -L-L, Xu J-B, Lin X-H, Zhang B, Jiang Q. Self-handicapping in Chinese medical students during the covid-19 pandemic: the role of academic anxiety, procrastination and hardiness. Front Psychol. 2021;12:741821. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.741821

45. Deva M, Dallaghan GLB, Howard N, Roman BJB. Faculty bridging individual and organizational resilience: results of a qualitative analysis. Med Educ Online. 2023;28(1). doi:10.1080/10872981.2023.2184744

46. Zeng YL, Zhang JH, Wei JX, Li SY. The impact of undergraduates’ social isolation on smartphone addiction: the roles of academic anxiety and social media use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15903.

47. Taleb OK, Siti-Azrin A, Sarimah A, Abusafia AH, Baharuddin KA, Wan-Nor-Asyikeen WA. Psychometric properties of the environmental factors’ questionnaire for undergraduate medical students taking online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1). doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04314-0

48. Cimsir E, Akdogan R. Inferiority feelings and internet addiction among Turkish University students in the context of COVID-19: the mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Current Psychol. 2023;1–10. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-04661-7

49. Sserunkuuma J, Kaggwa MM, Muwanguzi M, et al. Problematic use of the internet, smartphones, and social media among medical students and relationship with depression: an exploratory study. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0286424. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0286424

50. Zheng Y, Zheng SQ. Exploring educational impacts among pre, during and post COVID-19 lockdowns from students with different personality traits. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2023;20(1). doi:10.1186/s41239-023-00388-4

51. Xu LL, Wang ZH, Tao ZY, Yu CF. English-learning stress and performance in Chinese college students: a serial mediation model of academic anxiety and academic burnout and the protective effect of grit. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1032675.

52. Soares ME, Mosquera P. Fostering work engagement: the role of the psychological contract. J Bus Res. 2019;101:469–476. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.003

53. Jeske D, Axtell CM. The nature of relationships in e-internships: a matter of the psychological contract, communication and relational investment. J Work Organ Rev Psicol Trab y de Las Organ. 2018;34(2):113–121. doi:10.5093/jwop2018a14

54. Gazit L, Zaidman N, Van Dijk D. Career self-management perceptions reflected in the psychological contract of virtual employees: a qualitative and quantitative analysis. Career Dev Int. 2021;26(6):786–805. doi:10.1108/CDI-12-2020-0334

55. Lin CP, Chiu CK, Liu NT. Developing virtual team performance: an integrated perspective of social exchange and social cognitive theories. Rev Manag Sci. 2019;13(4):671–688. doi:10.1007/s11846-017-0261-0

56. Perneger TV, Courvoisier DS, Hudelson PM, Gayet-Ageron A. Sample size for pre-tests of questionnaires. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(1):147–151. doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0752-2

57. Wang W, Zhang Y, Wu H, Zhao J. Expectation and complaint: online consumer complaint behavior in COVID-19 isolation. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;2022:2879–2896.

58. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. In: Fiske ST, Schacter DL, Taylor SE, editors. Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 63. Annual Reviews; 2012:539–569.

59. Wang W, Zhang Y, Wu H, Zhao J. Expectation and complaint: online consumer complaint behavior in COVID-19 isolation. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:2879–2896. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S384021

60. Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Ringle CM. “PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet”–retrospective observations and recent advances. J Mark Theory Pract. 2022;54(4):1–15.

61. Wang W, Yang D, Zheng Y. How to believe? Building trust in food businesses’ consumers based on psychological contracts. Br Food J. 2023. doi:10.1108/BFJ-01-2023-0066

62. Dash G, Paul J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;173:121092.

63. Wang W, Zhang Y, Zhao J. Technological or social? Influencing factors and mechanisms of the psychological digital divide in rural Chinese elderly. Technol Soc. 2023;74:102307.

64. Kim JH. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72(6):558–569.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.