Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Influence of Narcissistic CEOs on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Choices: The Moderating Role of the Legal Environment

Authors Gao Q , Gao L, Long D , Wang Y

Received 9 April 2023

Accepted for publication 2 August 2023

Published 11 August 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 3199—3217

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S414685

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Qingzhu Gao,1 Liangmou Gao,1 Dengjie Long,2 Yuege Wang3

1School of Business Administration, Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, Dalian, Liaoning, People’s Republic of China; 2Marxism College, Party School of Chongqing Committee of C.P.C, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China; 3Faculty of Agribusiness and Commerce, Lincoln University, Lincoln, New Zealand

Correspondence: Dengjie Long, Marxism College, Party School of Chongqing Committee of C.P.C, 160 Yuzhou Road, Jiulongpo District, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 13036373662, Email [email protected]

Purpose: During recent years, there has been a growing interest in CSR across disciplines. Various scholars document that Chief Executive Officer (CEO) narcissism is an important factor that should not be overlooked when analyzing CSR. Research on the relationship between CEO narcissism and CSR has treated CSR as a whole construct. However, little attention has been paid to its effect on different dimensions of CSR, especially the same psychological trait may have effects on charitable donations and employee welfare. The purpose of the study is to explore the relationship between CEO narcissism and charitable donations and employee welfare, while taking into account the moderating role of the legal environment.

Methods: This study used the video survey method to measure CEO narcissism, the video information was obtained from Baidu.com and hao.360.com search engines. Other data were collected from Chinese Stock Market Research (CSMAR) database. We used OLS regression for data analysis and also used Tobit regression model to check the robustness of the estimation results. Meanwhile, all analyses will be performed with Stata 16.0 software.

Results: Empirical analysis reveals that CEO narcissism has a positive and significant impact on charitable donations and has a negative and significant impact on employee welfare. Moreover, the legal environment will reduce the effect of CEO narcissism on charitable donations and employee welfare, indicating that a stronger legal environment could attenuate the effect of CEO personality traits, especially narcissism on charity donations and employee welfare.

Conclusion: This study contributes to the behavioral finance theory and stakeholder theory to better understand the relationship between CEO narcissism and charitable donations and employee welfare. Meanwhile, this study is one of the few studies to investigate the patterns of CSR activities in China, an important emerging economy.

Keywords: CSR, CEO, legal environment, charitable donation, employee welfare, personality traits

Introduction

Research on corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been paying increasing attention to the antecedents, drivers, and motives of CSR. Much of the research could be classified into two major types: “outside-in” and “inside-out”. The “outside-in” perspective focuses on the incentives and constraints of the external institutional environment and the value drivers of external stakeholders. The former focuses on the regulation of CSR behavior from the formal system, which reflects the government’s facilitation approach to CSR through the formulation of rules and regulations (such as legal system, incentive system, evaluation system, and punishment system), and plays the governance function of the institutional entities in promoting CSR.1 The latter emphasizes the effect of the constraints of industry associations among external stakeholders,2 and the monitoring by the public on CSR behavior.3 The “inside-out” perspective focuses on the impact of entrepreneurship and top management team heterogeneity on CSR. The former emphasizes the role of social entrepreneurship in driving organizations to create economic and social value.4 The latter focuses on the impact of top management team characteristics, such as managerial compensation,5 marital status,6 political connection,7 poverty experience,8 and the CEOs’ psychological traits9 on CSR.

The personal characteristics of the firm’s top management team are specifically diverse, one of which is narcissism. Narcissism refers to a psychological construct involving personality traits, such as excessive egoism, self-superiority, lack of empathy, demands for admiration, control and power and self-image reinforcement that comes from external praise. Narcissism can be found among many groups of people, including CEOs.10 The intersection of CEO narcissism and CSR has also received limited attention. Evidence suggests that narcissistic CEOs are more likely to devote implementing CSR activities. For example, Petrenko confirmed that narcissistic CEOs will be more likely to undertake CSR activities to win admiration and applause.11 Evidence also shows that narcissistic CEOs will decrease CSR activities. For example, Lin found that CEO narcissism is negatively and significantly related to CSR in megaprojects.12 This study shows that the relationship between CEO narcissism and CSR is inconsistent and contradictory. This research will force us to think. Why does CEO narcissism influence CSR differently? What boundary conditions may influence this relationship?

Two reasons link the inconsistency of CEO narcissism and CSR choices. One reason is that narcissistic CEOs may make different behaviors when faced by different stakeholders.13 Behavioral finance theory argues that irrational personality characteristics of CEO could lead them to irrational choices. Stakeholder theory emphasizes that internal and external stakeholders have different impacts on firm’s behavior. Therefore, we believe that driven by their narcissistic traits, narcissistic CEOs may have differential impacts on internal and external stakeholders. By disentangling CSR activities into different types, a nuanced understanding of CEO narcissism and CSR choice may be achieved. Scholars have divided CSR activities into Internal CSR and External CSR activities.14 Internal CSR refers to Internal CSR practices that are related to internal stakeholders. Employee welfare can be regarded as a typical form of Internal CSR. External CSR refers to External CSR practices that are related to External stakeholders. External CSR typically includes activities such as cause-related charitable donations. On this basis, we tried to select charitable donations and employee welfare as the proxy variables of external and internal CSR, and then examine the impact of CEO narcissism on charitable donations and employee welfare. Another reason is that the relationship between CEO narcissism and CSR may be influenced by external factors. The legal environment is an important and distinct governance mechanism that affects the behavior of micro-enterprises.15 Stronger legal environment usually indicates well-developed legal systems, effective supervision and monitoring mechanisms, effective corporate governance mechanism and less self-interest behavior.16 In the analysis, we selected the legal environment as a moderator variable.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the influence of CEO narcissism on CSR-related choices and the moderating role of the legal environment. To test our ideas, first, we identified the target of CSR as the firm’s stakeholders and distinguished internal and external stakeholders based on whether there is a formal market transaction contractual relationship between the enterprise and its stakeholders,17 and then identified particular types of internal and external CSR practices (charitable donations and employee welfare). This is particularly important in the context of CEO narcissism affecting charitable donations and employee welfare. Second, the legal environment may be an effective external governance factor affecting the relationship between CEO Narcissism and CSR choices (charitable donations and employee welfare). China provides an appropriate setting for this study. In 2020, China received 225.313 billion yuan in charitable donations, social philanthropy grew steadily, however, firms often encroach on workers’ interests and rights. As China has experienced rapid economic growth, narcissistic tendencies which are growing and narcissistic CEOs are apt to emerge and flourish. Narcissistic tendencies which are growing and narcissistic CEOs are apt to emerge and flourish.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents our literature review and hypothesis development. Section 3 explains the sample and data, variables, and econometric model. Section 4 covers the descriptive statistics, regression results and robustness tests. Section 5 discusses the theoretical contribution, management enlightenment, limitations and future research of this paper. Section 6 present our findings.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

CEO Narcissism and Disentangling CSR

Narcissism stems from people’s inflated and fragile self-concept,18 characterized by self-worship, self-superiority, lack of empathy, exploitation.19 Unlike overconfidence and self-esteem, individuals with narcissistic personality desire for extreme amounts of attention and admiration.20 As a stable psychological and personality trait, narcissism is more common in business managers. Buchholz points out that many managers’ behaviors are driven by narcissistic traits.21 Brummelman argued that individuals with relatively high narcissism levels tend to emerge as managers.22 As the most powerful and influential individuals in top management team, narcissism is common among CEOs, such as Steve Jobs, former CEO of Apple Inc, Jack Ma, former CEO of Alibaba Corporation. Narcissistic CEOs contain both cognitive and motivational factors.23 Specifically, narcissistic CEOs have a higher inflated self-concept. Such inflated self-concept make them particularly confident in their judgment and abilities.24 Besides, narcissistic CEOs focus on realizing personal interests and are strongly motivated to attract attention and praise.

Behavioral finance theory emphasizes that individuals behave and their decisions are biased in situations of uncertainty, especially psychological characteristics, such as overconfidence, mental accounting, and narcissism, which will lead to irrational choices of individuals.25 Personality psychology research found that, driven by the irrational nature of narcissistic traits, CEOs often make irrational decisions.26 For example, narcissistic CEOs have been found to favor size over quantity when they make corporate acquisitions,27 pursue excessive R&D,28 pursue disruptive innovation.29 Such irrational behavior may be associated with more media coverage. In terms of CSR, Al-Shammari found that narcissistic CEOs tend to take actions to draw people’s attention.29 This finding is consistent with other studies that narcissistic CEOs often place a lot of emphasis on CSR to maintain or improve their personal reputation and gain social attention and applause. Recently, however, Gao went further and found that highly narcissistic leaders are motivated primarily by egoism and will satisfy personal needs results at the expense of employees.13 We can observe that the relationship between CEO narcissism and social responsibility is inconsistent. Such inconsistencies quite likely are due to narcissistic CEOs may hold varying attitudes toward different stakeholders.

Stakeholder theory emphasizes that the firm is a collection of stakeholders and realizes their interests.30 Stakeholder support contributes to the survival and growth of the firm, and it is the firm’s responsibility to create value for its stakeholders.31 A firm’s major stakeholders include institutions or individuals that affect the firm’s development goals, such as shareholders, employees, consumers, communities, governments. The firm has various stakeholders, and different stakeholders may have different interests, preferences, value expectations and impacts on firms’ development. Therefore, distinguishing among different stakeholder groups is an essential area in the stakeholder literature. Scholars have made many attempts to classify stakeholders. For example, based on whether the contract was signed, Esposito divided the selected key stakeholders into contractual stakeholders, community stakeholders.32 Based on three attributes: legitimacy, power and urgency, Marcon divided the selected key stakeholders into definitive stakeholders, expectant stakeholders and latent stakeholders.33 Based on the close ties between business organizations and firms, Ahinful divided the stakeholders into primary and secondary stakeholders.34 Although different scholars have different classifications of stakeholders, the measurement standard is essentially the same. That is, whether stakeholders affect a firm’s operational, and the basis of impact is whether stakeholders have a market transaction contract relationship with the firm.

Stakeholder theory suggests that a firm is a contractual collection of stakeholders.35 Stakeholders who entered into marketing contracts with the firm, such as shareholders, managers and employees, are defined as “internal stakeholders”. Stakeholders who do not have any contractual relationships with the firm are defined as “external stakeholders”, such as the government, social media, community and the public. Internal and external stakeholders have a differential effect on firm outcomes and may have different expectations in a firm’s CSR activities. Internal stakeholders put forward CSR requirements by self-interest; external stakeholders emphasized that CSR should be ethically based on norms. CSR practices are also aimed at internal and external stakeholders. Firm’s CSR activities related to external stakeholders are often defined as external CSR activities, which are more outward activities oriented. In comparison, firm’s CSR activities related to internal stakeholders is often defined as internal CSR activities, which are more inward activities oriented.36 Previous studies argue that the main form of external CSR was and remains charitable donations,37 and employee welfare as the typical proxy variables for internal CSR activities.38 Charity donations help to improve a firm’s prestige, prosocial image, and allow greater public endorsement. Employee welfare is deeply embedded in a firm’s human capital and regulations, which received far less attention from external stakeholders. In this analysis, driven by narcissistic irrational traits, narcissistic CEOs usually show different behavioral logics when considering what kind of CSR to undertake, that is, engaging in employee welfare based on the consideration of maximizing self-interests; and engaging in charitable donations based on the consideration of gaining attention and praise from external stakeholders.

CEO Narcissism and External Charitable Donations

Behavioral finance research suggests that CEO’s psychological traits are essential for the firms’ charitable donations. Narcissism is a crucial personality dimension of CEOs, characterized by desiring for power, attention, applause and praise. Driven by the irrational nature of narcissistic traits, narcissistic CEOs will influence organizational decisions and charitable giving. Based on the shareholder perspective, external stakeholders emphasize that CSR requires ethical norms. Charitable donations attract positive external attention and praise and help a firm obtain strong resources and support. We theorize that highly narcissistic CEOs are more likely to engage in donation activities to gain attention, praise, and resources from external stakeholders.

First, highly narcissistic CEOs will engage in donation activities to gain praise and attention from external stakeholders. Narcissistic CEOs are motivated to win the appreciation and praise of external stakeholders and must constantly search for the “external sources of narcissistic supply”.11 Affirmations and praise from external stakeholders are essential source of “narcissistic supply” for narcissistic CEOs.39 Charitable donation presents a substantial opportunity to garner the attention of external stakeholders. Therefore, narcissistic CEOs are likelier to engage in external donation activities to gain praise from external stakeholders, such as the media, consumers, and the government. Studies have found that narcissistic CEOs reputation-seeking drives them enthusiastic about public welfare.40

Second, highly narcissistic CEOs will engage in donation activities to demonstrate their ability and obtain the resources. Driven by the better-than-average effect, narcissistic CEOs are more willing to “grasp the nettle” to prove their ability.41 Relieving financing dilemma and improving operating performance is an effective way to demonstrate the ability of narcissistic CEOs. The charitable donation may convey credible corporate signals, and such signals would strengthen investor confidence and gain support from local banks and governments. Therefore, narcissistic CEOs will increase their donation behavior to gain stakeholders’ support and help firms better deal with financing issues. Narcissistic CEOs are more dominant and controlling.42 In particular, narcissistic CEOs prefer to be “market leaders” rather than “market followers”.43 As an effective channel for firms to obtain resources, charitable donations can obtain political, social and commercial resources, thereby improving market competitive advantage. Thus, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1: CEO narcissism positively influences charitable donations.

CEO Narcissism and Internal Employee Welfare

Stakeholder theory states that a firm is a collection of internal stakeholders with contractual relationships,35 whose growth depends on the collective contribution of internal stakeholders. Employees are the most critical internal stakeholders of the firm and have an essential impact on firm growth. Theoretically, the CEO is also an internal stakeholder. However, a CEO can be directly or indirectly contracted with employees on behalf of the firm and play a crucial role in corporate decision-making, so the CEO will affect the firm’s CSR commitment to employees. Some scholars consider narcissistic CEOs as “destructive leader”,29 believing they have negative traits, such as egoism and intellectual inhibition. Driven by negative traits, narcissistic CEOs may treat internal employees negatively and even reduce the employee’s welfare.

First, highly narcissistic CEOs are motivated to satisfy self-interest by exploiting others and are likelier to violate employees’ welfare. Highly narcissistic CEOs possess higher exploiting motivation at work, such as harshly criticizing employees, insulting employees, stealing employees’ achievements, and ultimately violating the interests of employees.44 Moreover, highly narcissistic CEOs are more deceptive and falsely concerned about employees. Such deceptive behavior will reduce employees’ trust and sense of belonging and increase employees’ tendency to leave. Our theory is consistent with the research of some scholars. For example, O’Reilly argued that narcissistic leaders give negative feedback to others when they perceive threats to their authority.45 Asad emphasized that narcissistic leaders have a significant indifference and inhibitory impact on subordinates.46

Second, highly narcissistic CEOs reduce employees’ welfare to maximize their firm’s market value. Based on the perspective of obtaining residual claims, employees’ welfare is usually considered as a short-term cost. Narcissistic CEOs often reduce internal transaction costs and employees’ welfare to obtain residual claims. Based on the perspective of attention-based view, employee responsibility is more closely related to the company’s rules, regulations and business operations. However, it needs long construction times and high operating costs. It is difficult for external stakeholders to identify the efforts of narcissistic CEOs in CSR. In contrast, charitable donations are more visible to the public and have the advantage of a short and sustainable implementation cycle.47 Narcissistic CEOs would focus more attention on charitable donations and reduce employee welfare benefits. Finally, given limited capital resources, there is no way to balance the resource investment of internal and external CSR. Specifically, excessive investment in charitable donations will crowd out employee welfare investment, and may result in lower investment in human capital. Thus, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2: CEO narcissism negatively influences employee welfare.

The Moderating Effect of the Legal Environment

As an important external governance mechanism, the legal environment is the environmental guarantee for the smooth operation of enterprises. The legal environment reflects the quality of legislation, administrative law enforcement, and enterprises’ compliance. A stronger legal environment could improve information disclosure quality, reduce encroachment, and restrain rent-seeking behavior.48 Charitable donations and employee welfare are social activities and will inevitably be guided and regulated by the legal environment. Especially in the context of “the rule of law” in China, the legal environment will profoundly affect the irrational CSR behavior of narcissistic CEOs.

First, a stronger legal environment could improve the quality of corporate information disclosure and constrain the narcissistic CEO’s manipulation of charitable donation and employee welfare. The legal environment provides a vital link between internal and external information. The interior information is conveyed to the exterior, regulators, analysts, and investors can quickly identify the inappropriate CSR behavior of narcissistic CEOs. When external stakeholders highly identify the irrational CSR behavior of narcissistic CEOs, the principal–agent problem might be reduced, and the destructive behavior of narcissistic CEOs will be suppressed.49 The exterior information is conveyed to the interior, narcissistic CEOs may obtain more valuable information on CSR duties and make more rational decisions.

Second, a stronger legal environment could raise the illegal cost of narcissistic CEOs, especially the illegal cost of encroaching upon employee rights and interests. Motivated by a strong desire for external praise and attention, narcissistic CEOs will focus more on external donations and make “excessive” charitable donation decisions. Although excessive charitable donations will attract public attention, they can also cover up violations (such as fictitious billing fraud, squeezing employee wages), divert the public’s attention, and escape merited punishment.50 At this juncture, a stronger legal environment could monitor narcissistic CEOs’ decision-making processes and constrain their illegal activities. In addition, a stronger legal environment could improve the protection of employees’ residual claims,51 reduce the probability of employees’ rights and interests being encroached upon,52 improve narcissistic CEOs’ supportive behavior and ultimately improve employee well-being. Thus, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3a: Legal environment weakens the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and charitable donations.

Hypothesis 3b: Legal environment weakens the negative relationship between CEO narcissism and employee welfare.

As mentioned above, we proposed a conceptual model of the study as shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Research model. |

Methodology

Sample and Data

The sample for our study started with all Chinese listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock from 2010 to 2019. We excluded companies in the following categories: (1) excluded banks, securities companies, and insurance companies; (2) excluded “ST” and “PT” companies; (3) excluded the company whose asset–liability ratio>1; (4) excluded companies with serious missing data; (5) excluded companies listed on the exchange less than 3 years; (5) excluded companies CEO’s less than 3 years. It is worth noting that, banks, securities companies, and insurance companies are dominated by intangible assets and capital structure different from other industries, which tends to affect the regression results. Therefore, they were deleted. Our final sample contains 605 observations. Data on charitable donation, employee welfare, CEO characteristics and firm characteristics were collected from Chinese Stock Market Research (CSMAR) database. Data on CEO narcissism were collected from a video survey methodology, and the video information was obtained from Baidu.com and hao.360.com search engines. Following prior research, we winsorize continuous at the 1% and 99% levels. Meanwhile, Stata is one of the most widely used statistical software, all studies in this analysis were conducted with Stata 16.0 software.

Variables

Independent Variables

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) is the prevailing instrument for measuring narcissism.53 However, the Narcissistic Personality Inventory has many question options, and CEOs in Chinese listed firms are unlikely to answer these questions about sensitive traits such as narcissism.54 The ratings of video samples provide valid access to measure CEO narcissism. The video approach has been used to assess CEO narcissism, which requires trained raters to watch the video of CEOs and give a numerical score on a set of items that measures CEO narcissism.55 The higher the average score given by the raters, the higher the narcissism of the CEO. Following prior research,11,40 we used the ratings of video samples to measure CEO narcissism (Nar).

First, drawing on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory developed by Raskin,56 and the narcissistic dimensions delineated by Emmons,57 we compiled the Narcissism Personality inventory (NPI-16) for Chinese CEOs (Table 1). The professors and managers were asked to evaluate and revise the Narcissism Personality Inventory, a modified CEO narcissism personality inventory that consists of 16 items spanning 4 dimensions. The 4 dimensions, namely: (1) entitlement/exploitativeness; (2) authority/leadership; (3) superiority/arrogance; (4) self-admiration/self-absorption. The NPI-16 uses a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 7 (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). Table 1 presents the details of the 16-item measure.

|

Table 1 Narcissistic Personality Index of CEO |

Second, followed Petrenko,11 we obtained CEO’s videos from Baidu.com and hao.360.com search engines. We classified the videos into 5 groups by length (1–3 minutes, 3–5 minutes, 5–10 minutes, 10–30 minutes, and more than 30 minutes). To ensure the validity and credibility of the CEO’s narcissism measurement, we set up a “pre-measuring method”. Specifically, we created a random subsample of CEOs (n = 30) to analyze mean differences between different videos for the same CEO. We found no significant differences in the narcissism measure between different videos for the same CEO (p>0.1). To avoid the effect of rater exhaustion on the evaluation work, we evaluated CEO’s video for 5–10 minutes.

Third, we developed the samples and procedures for rating and trained the raters. Specifically, we recruited 12 graduate students in psychology with experience in personality assessment as raters. Raters received training and offered a monetary incentive to participate. Raters were told that the focus of the study was to get their perceptions of the CEOs’ psychological traits in the video sample. Their answers were kept strictly confidential. After the training, raters were given an individual password to login the system which was embedded in video sample surveys. Password updated in each login. For each CEO, two raters were selected and assigned randomly. Raters were required to watch the videos independently and rated each CEO’s narcissism tendencies using a 7-point Likert scale in each sample video. We also created an Excel spreadsheet that consists of the NPI-16 scale, for the raters to rate each CEO’s narcissism tendencies and give justifications for their rating. The justifications indicate the reasons why raters give narcissistic CEOs a particular score. All ratings were performed within 2 weeks, and each subject in the video was limited to not more than an hour.

Fourth, we compared the difference in the rating scores to derive the CEO narcissism index. We followed Fung, and if the difference in the rating of the CEO scores between two raters was bigger than one standard deviation of the total sample, we selected another two raters to reassess the CEO’s narcissism.58 If only one rater had a score significantly different from others (bigger than one standard deviation), the rater’s score was excluded, and we selected the average of the other three raters’ scores to derive the narcissism index for CEO. If the scores of the four raters differed, we found additional videos and asked the raters to re-assess.

Dependent Variables

Charitable donations can be broadly considered a particular external CSR. Scholars define charitable donation as the voluntary donation of money and time to an organization or individual.59 The absolute value of charitable donation can reflect the objective level of corporate charitable donation. We followed Brown, charitable donation (Don) = Ln (Total annual charitable donation + 1).60 Employee welfare is a significant predictor of internal CSR. The internal CSR described in our research focuses on employee welfare, and the social insurance benefits can measure internal welfare. We followed Zhu, employee welfare (Welf) = total annual employees’ social insurance/operating income.61

Moderator Variables

We followed Wang's method and used “the development of market intermediary organizations and the legal environment” to measure the legal environment (Legal).62 The legal environment consists of the development of legal intermediary organizations, the protection of legitimate rights and interests of producers, the protection of intellectual property rights and consumer rights. The legal environment index has been recognized by scholars and used to measure the legal environment in China, such as Chen.63 The higher the legal environment index, the stronger the legal environment.

Control Variables

We accounted for several control variables, including firm, the CEO, industry and year. First, firm characteristic variables include firm size, firm age, firm leverage, R&D investment, government subsidies, independent directors and board size. Large firms have more resources and invest in CSR than small firms. We measured Size (firm size) using the natural logarithm of the number of employees. Firm age affects firm’s CSR initiative. We measured Age (firm age) using the number of years the firm has been in business. Asset–liability ratio is an important indicator to measure a firm’s financial performance and a fundamental factor influencing CSR engagement. We defined Lev (firm leverage) as total liabilities scaled by total assets. R&D investment improves the firm’s CSR performance. Rdi (R&D investment) was measured as R&D expenditures to total sales. Government subsidy provides a positive signal about firm’s quality that facilitates attracting venture capital. We measured Sub (Government subsidy) using the natural logarithm of the amount of annual government subsidies. Independent directors may guide and monitor business activities, including oversight of CSR activities. Dudb (independent directors) was measured as the ratio of independent directors to the total number of board members. Board size reflects the board’s ability to participate in major CSR decisions and supervise managers. We measured Board (Board size) using the natural logarithm of the total number of board members. Second, we also control for CEO gender, CEO age, CEO shareholdings. We operationalized Gend (CEO gender) as a dummy variable, where 1 indicates males, 0 indicates females. Lage (CEO age) is the age of the CEO in years. Hold (CEO shareholdings) was measured as the percentage of the firm’s total shares owned by the CEO. Finally, we also controlled for industry-effect and year-effect in all our models.

Econometric Model

To test our hypotheses, we established the following models.

Where Don means the charitable donations, Welf means the employee welfare, Nar means the estimated narcissism of CEO, ε stands for error terms, i and t mean firms and years, respectively. The coefficient of primary interest is α1, which should be positive and statistically significant if the CEO’s narcissism affects charitable donations, consistent with hypothesis 1. Another coefficient of primary interest is β1, which should be negative and statistically significant if the CEO’s narcissism affects the employee welfare, consistent with hypothesis 2.

Nar x Legal means the interaction between CEO narcissism and the legal environment. The interaction coefficient is μ2 which should be negative and statistically significant if the legal environment weakens the relationship between CEO narcissism and charitable donation, consistent with hypothesis 3a. Another interaction coefficient is μ2, which should be positive and statistically significant if the legal environment weakens the relationship between CEO narcissism and employee welfare, consistent with hypothesis 3b.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

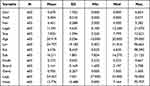

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for all variables. Several points are worth nothing. First, our standardized measure of narcissism ranges from a minimum of 3.500 and a maximum of 5.282, indicating that most Chinese CEOs in the sample tend to be more narcissistic. Second, the mean of our dependent variable “Don” is 0.670, the standard error is 1.762, indicating that the sample firms make more charitable contributions. The mean of “Welf” is 0.004, the standard error is 0.010, and the maximum value is 0.077, indicating that the sample firms have poorer performance in employee welfare. Third, the mean value of our moderating variable “Legal” is 11.591, the standard error is 4.635, indicating that there is wide variation under legal environment for firms. Fourth, the mean value of Size, Age, Sub and Board is larger than the standard errors, indicating that there is wide variation among firms Size, Age, Sub and Board. Fifth, the mean of Lev is 34.757, and the maximum value is 96.662, indicating that the sample firms have relatively higher asset-liability ratios. The mean of Dudb is 0.372, which is consistent with the board should consist of one-third of independent directors. The mean of Gend is 0.955, which implies nearly 96% of CEOs are men. Finally, the other control variables are consistent with earlier theoretical expectations.

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics |

Table 3 reports the correlations among relevant variables. First, the correlation coefficient is less than 0.700, indicating that no strong bivariate correlation exists between these variables. Second, the average variance inflation factors (VIF) for all regression models are smaller than 3, indicating that there are no serious multicollinearity issues in our regression analyses. Finally, we find a positive correlation between CEO narcissism and charitable donations, which, in light of the first hypothesis, indicates that firms with narcissistic CEOs may donate more. We also find a significant and negative correlation between CEO narcissism and employee welfare, which, in light of the second hypothesis, indicates that firms with narcissistic CEOs tend to undertake less employee welfare. The above results show that our research topic is feasible.

|

Table 3 Main Variables Correlation Matrix |

Regression Results

Table 4 presents the results of the OLS model to investigate the effect of CEO narcissism on charitable donations and employee welfare, and the moderating role of Legal (the legal environment). Model 1 is the baseline model that includes only control variables. Model 2 adds CEO narcissism as an independent variable to examine the direct effect of CEO narcissism on charitable donations. Model 3 adds the interaction of CEO narcissism and Legal to examine the moderating effect of Legal on the link between CEO narcissism and charity donations. Meanwhile, model 4 includes control variables only. Model 5 adds CEO narcissism to examine the direct effect of CEO narcissism on employee welfare. Model 6 adds the interaction of CEO narcissism and Legal to examine the moderating effect of Legal on the relationship between CEO narcissism and employee welfare.

|

Table 4 Regression Results |

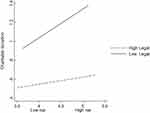

As shown in model 2, CEO narcissism is significantly and positively associated with the charity donations (β = 0.284, ρ< 0.05), supporting hypothesis 1. In model 5, CEO narcissism is significantly and negatively associated with the employee welfare (β = −0.006, ρ < 0.01), supporting hypothesis 2. As shown in model 3, CEO narcissism is significantly and positively (β = 1.247, ρ< 0.01), the interaction of CEO narcissism and Legal is negatively and significantly (β = −0.083, ρ< 0.05) (Figure 2), which largely indicates that the legal environment will weaken the positive effect of CEO narcissism on charitable donations, supporting hypothesis 3a. In model 6, CEO narcissism is negatively and significantly (β = −0.014, ρ< 0.01), the interaction of CEO narcissism and Legal is positively and significantly (β = 0.001, ρ< 0.01) (Figure 3). These results clearly imply that the legal environment will weaken the negative effect of CEO narcissism on employee welfare, supporting hypothesis 3b.

|

Figure 2 The Moderating effect of the legal environment on the relationship between CEO narcissism and charitable donations. |

|

Figure 3 The Moderating effect of the legal environment on the relationship between CEO narcissism and employee welfare. |

Robustness Tests

To ensure the robustness of our results, we took several steps. First, a potential issue of endogeneity between CEO narcissism and charity donations and employee welfare may arise. To address this problem to some extent, we use the Tobit model because our dependent variables had many zero values. The Tobit regression model assumes that the range of a dependent variable is limited, eg, the minimum value of the variable is zero. For our study, charitable donations and employee welfare contained many observations with a zero value. Thus, the dependent variables fit well with Tobit estimation. Models 1–4 in Table 5 shows the results of the Tobit model. Models 1–2 show the regression result for the charity donation as a dependent variable. The result shows the effect of the estimated CEO narcissism on charity donation, which is positive and significant at the 10% level (β = 0.284, p < 0.1), supporting H1. Model 2 shows the positive and significant effect of CEO narcissism at the 1% level (β = 1.247, p < 0.01), and the coefficient of the interaction of CEO narcissism and Legal is negative and significant (β = −0.083, p < 0.05), supporting H3a. Similarly, models 3–4 show the regression result for the employee welfare as a dependent variable. The result shows the effect of the CEO narcissism on employee welfare, which is negative and significant at the 1% level (β = −0.006, p < 0.01), supporting H2. Model 4 shows that CEO narcissism has a negative and significant coefficient (β = −0.014, ρ< 0.01), the coefficient of the interaction of CEO narcissism and Legal is positive and significant (β = 0.001, ρ< 0.01), supporting H3b.

|

Table 5 Robustness Tests |

Second, we reran the analysis using an alternate measure for charity donation, namely, operationalized charity donation as a dummy variable, where 1 indicates donations greater than 0 and 0 indicates no donations. Meanwhile, we used the natural logarithm of employees’ social insurance to operating income as a substitute measure of Welf. Model 5 shows that the coefficient estimate of CEO narcissism is positive (β = 0.055, p <0.1), supporting Hypothesis 1. Model 7 shows that the coefficient estimate of CEO narcissism is negative (β = −0.625, p <0.1), supporting Hypothesis 2. Model 6 shows that the coefficient estimate of CEO narcissism is positive (β = 0.226, p <0.05), and the coefficient estimate of interaction is negative (β = −0.015, p <0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 3a is supported. Model 8 shows that the coefficient estimate of CEO narcissism is negative (β = −2.995, p <0.01), and the coefficient estimate of interaction is positive (β = 0.240, p <0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 3b is supported.

Discussion

Current research on narcissistic CEOs and CSR has yielded inconsistent results. Some studies have shown that highly narcissistic CEOs engage their firms in more CSR initiatives as a way to attract attention and praise.64 Other studies have suggested that highly narcissistic CEOs might be negatively related to CSR.12 These inconsistent results may occur because narcissistic CEOs selectively focus on and engage in CSR activities. If so, how CEO narcissism affects CSR choice? What factors may influence the relationship? However, few studies have examined the relationship between CEO narcissism and specific CSR activities, especially different dimensions of CSR. To address this research gap, we developed a model of the relationship between CEO narcissism and CSR based on the behavioral finance theory and the stakeholder theory. Then we defined External CSR activities and Internal CSR activities and tried to select charitable donations and employee welfare as the proxy variables of external and internal CSR. On this basis, we investigated how CEO narcissism influences CSR choices (charitable donations and employee welfare), and how legal environment moderates the effect of CEO narcissism on CSR choices.

The findings of our research indicate that CEO narcissism has a direct positive impact on charitable donations. This result is consistent with the research of Yang.65 From the motivational perspective, narcissistic CEOs are motivated to enhance their image and self-esteem, reinforce their views and win the praise of external stakeholders.10 From the behavioral perspective, narcissistic tendency drives CEOs to pursue continuous and chronic praise, attention and approbation. Meanwhile, narcissistic CEOs must regularly perform tasks that are visible to the public. Charitable donations take a relatively short period, incurs low cost and are easy to implement, pretty transparent and visible for external stakeholders to recognize.9 This suggests that charitable donations are an important “narcissistic supply tool” for narcissistic CEOs to seek attention and praise from external stakeholders.29 Therefore, narcissistic CEOs will be more inclined to engage in charitable activities. In contrast, we also found that CEO narcissism has a direct negative impact on employee welfare. That is, CEOs with high levels of the narcissistic triad might maximize the effects of self-interest on employee welfare, which would reduce the employee welfare. This is not completely surprising. Previously, Tang emphasized that hubristic CEOs, who share some of its features with narcissistic CEOs, negatively affect CSR initiatives.66 Reasons for this may be that narcissistic CEOs do not consider employee welfare as their approach to gain praise, attention and admiration, and it is difficult to implement. This finding successfully addressed the inconsistent relationship between CEO narcissism and CSR, and also highlights the impact of CEO narcissism on charitable donations and employee welfare.

More importantly, our research discovered that the level environment moderated the effect of CEO narcissism on charitable donations and employee welfare. Under the influence of the legal environment, the irrational behavior of narcissistic CEOs will be suppressed. Previous empirical studies have primarily focused on the effect of board gender diversity,10 outside board of directors67 and corporate governance68 on the relationship between CEO narcissism and CSR, leaving limited research on the legal environment. As evidenced by the results of this study, the legal environment is an important external governance mechanism, which will force companies to improve their operating efficiency by strengthening the quality of information disclosure, restraining interest embezzlement and misuse power behaviors, and weakening the opportunism of managers.69 More specifically, a stronger legal environment could monitor narcissistic CEOs’ decision-making processes and constrain their illegal activities. Meanwhile, a stronger legal environment could improve the protection of employees’ residual claims, reduce the probability of employees’ rights and interests being encroached upon. Taken together, our research fills the theoretical gap between CEO narcissism and CSR choices (charitable donations and employee welfare). We enrich the behavioral finance theory and the stakeholder theory, innovatively introduce these theories into the relationship between CEO narcissism and CSR choices, expand the research perspective of these theories, and provide empirical evidence for these theories and their effectiveness.

Theoretical Contribution

Drawing on behavioral finance theory and stakeholder theory, this study provides insights into listed firms’ charitable donations and employee welfare in China by examining the effect of CEO narcissism, a relatively unexplored area in psychology and organizational behavior. We make three contributions to the extant literature. First, our study is a modest contribution to the CSR literature by establishing a precise relationship between CEO narcissism and two types of CSR choices (charitable donations and employee welfare). Researchers have previously focused on general CSR activities and examined the antecedents of CSR aggregately, whereas only a few studies have focus on a typology of CSR.13,66 By elaborating how a CEO’s narcissism can affect a firm’s CSR choices (charitable donations and employee welfare), we respond to the call on how managers prioritize and balance aspects of CSR activities. In particular, our research verified that highly narcissistic CEOs tend to increase charitable donations and reduce employee welfare, indicating that narcissistic CEOs may be a crucial force in causing the gap between external and internal CSR investments. Second, deepening the dialogue between CEO narcissism and CSR (charitable donations and employee welfare). Building on the stakeholder theory, we distinguished between external and internal CSR activities and carefully selected charitable donations and employee welfare to examine the impact of CEO narcissism. This study shows that the irrational narcissism traits will drive the willingness of narcissistic CEOs to invest in CSR. We found that increasing firm donations and reducing employee welfare is a manifestation of the irrational behavior of narcissistic CEOs. Our results clarify the relationship between CEO narcissism and CSR choices and provide a new perspective for scholars to discuss relevant issues. Third, our study expands the boundary conditions under which the influence of narcissistic CEOs on CSR choices. This study shows that under strong legal environment, narcissistic CEOs will be willing to reduce excessive charitable donations and improve employee welfare benefits. Thus, our results enhance the understanding of the boundary conditions of the legal environment on CSR in emerging economies and enrich the research on the CEO’s narcissistic right change perspective. Moreover, our findings support the view that CEO’s narcissistic personality influences CEO’s strategy and decision-making, contributing to the literature on the behavioral finance theory by connecting the CEO’s psychological characteristics to charitable donations and employee welfare.

Management Enlightenment

Our findings have important practical implications for selecting CEOs, disciplining a firm’s CSR behavior and balancing stakeholder interests. First, recognize the CSR behavior of narcissistic CEOs. When electing and appointing the CEO, the firm should not just pay special attention to CEO’s working experience, ability structure, and social relationships but also explore the CEO’s personality and psychological characteristics. Firms should identify the high-profile CSR activities of narcissistic CEOs and protect the employee’s legitimate interests. There is a “bright side” to narcissistic CEOs. Especially for companies facing intense competition, seeking a change in strategy and focusing on open innovation, narcissistic CEOs can benefit firms. Second, this study provides evidence for forming firm-specific external governance mechanisms. A stronger legal environment could improve the quality of corporate governance practices and weaken CEO narcissism’s direct effect on excessive investments in charitable donation and poor investments in employee welfare. Government needs to transform its functions, ensure the power is rationally allocated, and thus help to improve the legal environment. Government should establish communication mechanisms among enterprises to understand corporate charitable contributions and employee welfare by organizing symposiums and surveying firms. Government should strengthen the establishment of judicial mechanisms to resolve the potential conflicts of interest between a firm’s CEO and its stakeholders, and then provide an institutional guarantee for CSR activities. Third, our results provide a crucial basis for balancing the internal and external CSR. Investing in CSR activities should strike a balance between both internal and external CSR. On the one hand, charitable donations can be an effective tool for firms to gain political and social capital resources. Therefore, companies engaging in donation activities should do so in the right way. On the other hand, employees can be valuable assets to an enterprise. The business should create a win–win situation where narcissistic CEOs should voluntarily implement policies to promote workers’ health.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study is not without limitations. First, we used the video survey method to measure CEO narcissism. The video approach is a method rapidly gaining acceptance in the literature. This method requires trained raters to watch a video of the CEO and give a numerical score on a set of items that measure the narcissistic CEOs. However, raters’ expertise levels and attitudes may affect the assessments, resulting in bias when measuring narcissistic CEOs. Future research may focus on reasonable and comprehensive indicators to measure CEO narcissism and find more comprehensive and precise measures for charitable donations and employee welfare. Second, we examined the moderating effect of the legal environment on CEO narcissism and charitable donations and employee welfare. Future research should examine the moderating effect of internal corporate governance mechanisms. Third, as the top leaders of the company, the CEO and board chair might affect a company’s CSR actions. Our study only examined the effect of narcissistic CEOs on charitable donations and employee welfare, and future research can benefit from other theories, such as the upper echelons and the attention-based view, which may affect corporate decisions on CSR. Besides, our study only focused on the Chinese firms, and future research could extend these predictions to other developed countries.

Conclusion

Guided by behavioral finance theory and stakeholder theory, this study explored how a CEO’s narcissism can affect a firm’s CSR choices and then explored the boundary conditions of CEO narcissism effects. The results showed that: (1) narcissistic CEOs have different behavioral logics and manifestations when undertaking CSR and will engage selectively in CSR activities. Specifically, narcissistic CEOs are likelier to increase firms’ charity donations and may cut employee welfare benefits. Narcissistic CEOs tend to increase charitable donations by gaining desire, attention, recognition, and acclaim from external stakeholders. Moreover, the egoistic, distrustful, and oppositionality nature of narcissistic traits will inhibit employees’ welfare. (2) The legal environment would attenuate the positive effect of CEO narcissism on charity donations and attenuate the negative effect of CEO narcissism on employee welfare. Our results showed that a stronger legal environment could improve the quality of corporate information disclosure, raise the illegal cost of encroaching upon employee rights and interests, and attenuate the effect of CEO personality traits, especially narcissism, on charity donations and employee welfare.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request [email protected].

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dongbei University of Finance and Economics and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. We explicitly informed the raters of the objectives of the study and guaranteed their confidentiality and anonymity. Meanwhile, all raters voluntarily made their decision to complete surveys.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by Chongqing Social Science Planning and Cultivation Project (NO.2020PY54), Major Program of the National Social Science Funds of China (11&ZD153), Graduate Research Project of School of Business Administration in Dongbei University of Finance and Economics (GSY202321), China National Annual Fund for Philosophy and Social Sciences in 2019 (NO.19BKS117).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Harasheh M, Provasi R. A need for assurance: do internal control systems integrate environmental, social, and governance factors? Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2023;30(1):384–401. doi:10.1002/csr.2361

2. Gold M, Preuss L, Rees C. Moving out of the comfort zone? Trade union revitalisation and corporate social responsibility. J Ind Relat. 2020;62(1):132–155. doi:10.1177/002218561985447

3. Chu SC, Chen HT, Gan C. Consumers’ engagement with corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication in social media: evidence from China and the United States. J Bus Res. 2020;110:260–271. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.036

4. Crupi A, Liu S, Liu W. The top‐down pattern of social innovation and social entrepreneur-ship. Bricolage and agility in response to COVID‐19: cases from China. R&D Manage. 2022;52(2):313–330. doi:10.1111/radm.12499

5. Velte P. Do CEO incentives and characteristics influence corporate social responsibility (CSR) and vice versa? A literature review. Soc Responsib J. 2019;16(8):1293–1323. doi:10.1108/SRJ-04-2019-0145

6. Shahzadi G, Qadeer F, John A, Jia F. CSR and identification: the contingencies of employees’ personal traits and desire. Soc Responsib J. 2020;16(8):1239–1251. doi:10.1108/SRJ-04-2018-0090

7. Zhou P, Arndt F, Jiang K, Dai W. Looking backward and forward: political links and environmental corporate social responsibility in China. J Bus Ethics. 2021;169:631–649. doi:10.1007/s10551-020-04495-4

8. Zhang Z, Wang X, Jia M. Poverty as a double‐edged sword: how CEOs’ childhood poverty experience affect firms’ risk taking. Brit J Manage. 2022;33(3):1632–1653. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12515

9. Al-Shammari M, Rasheed AA, Banerjee SN. Are all narcissistic CEOs socially responsible? An empirical investigation of an inverted U-shaped relationship between CEO narcissism and corporate social responsibility. Group Organ Manage. 2022;47(3):612–646. doi:10.1177/10596011211040665

10. Lassoued N, Khanchel I. Voluntary CSR disclosure and CEO narcissism: the moderating role of CEO duality and board gender diversity. Rev Manag Sci. 2023;17(3):1075–1123. doi:10.1007/s11846-022-00555-3

11. Petrenko OV, Aime F, Ridge J, et al. Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strategic Manage J. 2016;37(2):262–279. doi:10.1002/smj.2348

12. Lin H, Sui Y, Ma H, et al. CEO narcissism, public concern, and megaproject social responsibility: moderated mediating examination. J Manage Eng. 2018;34(4):04018018. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.000062

13. Gao Q, Gao L, Long D, Wang Y. Chairman Narcissism and Social Responsibility Choices: the Moderating Role of Analyst Coverage. Behav Sci. 2023;13(3):245. doi:10.3390/bs13030245

14. Zhong X, Ren G, Wu X. Not all stakeholders are created equal: executive vertical pay disparity and firms’ choice of internal and external CSR. Rev Manag Sci. 2022;16(8):2495–2525. doi:10.1007/s11846-021-00502-8

15. Bradshaw M, Liao G, Ma MS. Agency costs and tax planning when the government is a major shareholder. J Account Econ. 2019;67(2–3):255–277. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2018.10.002

16. Cumming D, Zhang M. Angel investors around the world. J Int Bus Stud. 2019;50:692–719. doi:10.1057/s41267-018-0178-0

17. Heuer MA, Khalid U, Seuring S. Bottoms up: delivering sustainable value in the base of the pyramid. Bus Strateg Environ. 2020;29(3):1605–1616. doi:10.1002/bse.2465

18. Liu X, Mao JY, Zheng X, Ni D, Harms PD. When and why narcissism leads to taking charge? The roles of coworker narcissism and employee comparative identity. J Occup Organ Psych. 2022;95(4):758–787. doi:10.1111/joop.12401

19. Nie X, Yu M, Zhai Y, Lin H. Explorative and exploitative innovation: a perspective on CEO humility, narcissism, and market dynamism. J Bus Res. 2022;147:71–81. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.061

20. Neave L, Tzemou E, Fastoso F. Seeking attention versus seeking approval: how conspicuous consumption differs between grandiose and vulnerable narcissists. Psychol Market. 2020;37(3):418–427. doi:10.1002/mar.21308

21. Buchholz F, Lopatta K, Maas K. The deliberate engagement of narcissistic CEOs in earnings management. J Bus Ethics. 2020;167:663–686. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04176-x

22. Brummelman E, Nevicka B, O’Brien JM. Narcissism and leadership in children. Psychol Sci. 2021;32(3):354–363. doi:10.1177/0956797620965536

23. Lee JY, Ha YJ, Wei Y, Sarala RM. CEO Narcissism and Global Performance Variance in Multinational Enterprises: the Roles of Foreign Direct Investment Risk‐Taking and Business Group Affiliation. British J Manage. 2023;34(1):512–535. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12592

24. Heavey C, Simsek Z, Fox BC, Hersel MC. Executive confidence: a multidisciplinary review, synthesis, and agenda for future research. J Manage. 2022;48(6):1430–1468. doi:10.1177/01492063211062566

25. Baker HK, Kumar S, Goyal N, Gaur V. How financial literacy and demographic variables relate to behavioral biases. Manag Financ. 2019;45(1):124–146. doi:10.1108/MF-01-2018-0003

26. Holm HJ, Nee V, Opper S. Strategic decisions: behavioral differences between CEOs and others. Exp Econ. 2020;23:154–180. doi:10.1007/s10683-019-09604-3

27. Aabo T, Als M, Thomsen L, Wulff JN. Watch me go big: CEO narcissism and corporate acquisitions. Rev Behav Finance. 2021;13(5):465–485. doi:10.1108/RBF-05-2020-0091

28. Ham C, Seybert N, Wang S. Narcissism is a bad sign: CEO signature size, investment, and performance. Rev Account Stud. 2018;23:234–264. doi:10.1007/s11142-017-9427-x

29. Al-Shammari M, Rasheed A, Al-Shammari HA. CEO narcissism and corporate social responsibility: does CEO narcissism affect CSR focus? J Bus Res. 2019;104:106–117. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.005

30. Freudenreich B, Lüdeke-Freund F, Schaltegger S. A stakeholder theory perspective on business models: value creation for sustainability. J Bus Ethics. 2020;166:3–18. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04112-z

31. Dmytriyev SD, Freeman RE, Hörisch J. The relationship between stakeholder theory and corporate social responsibility: differences, similarities, and implications for social issues in management. J Manage Stud. 2021;58(6):1441–1470. doi:10.1111/joms.12684

32. Esposito De Falco S, Scandurra G, Thomas A. How stakeholders affect the pursuit of the Environmental, Social, and Governance. Evidence from innovative small and medium enterprises. Corp Soc Resp Env Ma. 2021;28(5):1528–1539. doi:10.1002/csr.2183

33. Marcon Nora GA, Alberton A, Ayala DHF. Stakeholder theory and actor‐network theory: the stakeholder engagement in energy transitions. Bus Strateg Environ. 2023;32(1):673–685. doi:10.1002/bse.3168

34. Ahinful GS, Tauringana V, Essuman D, Boakye JD, Sha’ven WB. Stakeholders pressure, SMEs characteristics and environmental management in Ghana. J Small Bus Entrep. 2022;34(3):241–268. doi:10.1080/08276331.2018.1545890

35. Jensen MC, Meckling WH. Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ. 1976;3(4):305–360. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

36. Chatzopoulou E-C, Manolopoulos D, Agapitou V. Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: interrelations of external and internal orientations with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J Bus Ethics. 2022;179(3):795–817. doi:10.1007/s10551-021-04872-7

37. Virador LB, Chen LF. Does an (in) congruent corporate social responsibility strategy affect employees’ turnover intention? A configurational analysis in an emerging country. Bus Ethics Env Resp. 2023;32(1):57–73. doi:10.1111/beer.12475

38. Macassa G, McGrath C, Tomaselli G, Buttigieg SC. Corporate social responsibility and internal stakeholders’ health and well-being in Europe: a systematic descriptive review. Health Promot Int. 2021;36(3):866–883. doi:10.1093/heapro/daaa071

39. Chen J, Zhang Z, Jia M. How CEO narcissism affects corporate social responsibility choice? Asia Pac J Manag. 2021;38:897–924. doi:10.1007/s10490-019-09698-6

40. Zhu DH, Chen G. CEO narcissism and the impact of prior board experience on corporate strategy. Admin Sci Quart. 2015;60(1):31–65. doi:10.1177/0001839214554989

41. Uppal N. CEO narcissism, CEO duality, TMT agreeableness and firm performance: an empirical investigation in auto industry in India. Eur Bus Rev. 2020;32(4):573–590. doi:10.1108/EBR-06-2019-0121

42. Zengin‐Karaibrahimoglu Y, Emanuels J, Gold A, Wallage P. Audit committee strength and auditors’ risk assessments: the moderating role of CEO narcissism. Int J Audit. 2021;25(3):661–674. doi:10.1111/ijau.12243

43. Kashmiri S, Nicol CD, Arora S. Me, myself, and I: influence of CEO narcissism on firms’ innovation strategy and the likelihood of product-harm crises. J Acad Market Sci. 2017;45(5):633–656. doi:10.1007/s11747-017-0535-8

44. Zhang L, Lou M, Guan H. How and when perceived leader narcissism impacts employee voice behavior: a social exchange perspective. J Manage Organ. 2022;28(1):77–98. doi:10.1017/jmo.2021.29

45. O’Reilly CA, Chatman JA. Transformational leader or narcissist? How grandiose narcissists can create and destroy organizations and institutions. Calif Manage Rev. 2020;62(3):5–27. doi:10.1177/0008125620914989

46. Asad S, Sadler-Smith E. Differentiating leader hubris and narcissism on the basis of power. Leadership-London. 2020;16(1):39–61. doi:10.1177/1742715019885763

47. Sarason Y, Hanley G. Embedded corporate social responsibility: can’t we do better than GE, Intel, and IBM? How about a benefit corporation? Ind Organ Psychol. 2013;6(4):354–358. doi:10.1111/iops.12066

48. Short JL, Toffel MW. Making self-regulation more than merely symbolic: the critical role of the legal environment. Admin Sci Quart. 2010;55(3):361–396. doi:10.2189/asqu.2010.55.3.361

49. Kontesa M, Brahmana R, Tong AHH. Narcissistic CEOs and their earnings management. J Manage Gov. 2021;25:223–249. doi:10.1007/s10997-020-09506-0

50. Wu B, Jin C, Monfort A, et al. Generous charity to preserve green image? Exploring link-age between strategic donations and environmental misconduct. J Bus Res. 2021;131:839–850. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.040

51. Naidu S, Posner EA. Labor Monopsony and the Limits of the Law. J Hum Resour. 2022;57(S):S284–S323. doi:10.3368/jhr.monopsony.0219-10030R1

52. Brinchmann B, Widding‐Havneraas T, Modini M, et al. A meta‐regression of the impact of policy on the efficacy of individual placement and support. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2020;141(3):206–220. doi:10.1111/acps.13129

53. Raskin R, Terry H. A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(5):890–902. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.890

54. Marquez-Illescas G, Zebedee AA, Zhou L. Hear me write: does CEO narcissism affect disclosure? J Bus Ethics. 2019;159:401–417. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-3796-3

55. Qiao P, Fung A, Fung H-G, Ma X. Resilient leadership and outward foreign direct investment: a conceptual and empirical analysis. J Bus Res. 2022;144:729–739. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.02.053

56. Raskin RN, Hall CS. A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychol Rep. 1979;45(2):590. doi:10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590

57. Emmons RA. Factor analysis and construct validity of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. J Pers Assess. 1984;48(3):291–300. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_11

58. Fung HG, Qiao P, Yau J, et al. Leader narcissism and outward foreign direct investment: evidence from Chinese firms. Int Bus Rev. 2020;29(1):101632. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101632

59. Kummer M, Slivko O, Zhang X. Unemployment and digital public goods contribution. Inform Syst Res. 2020;31(3):801–819. doi:10.1287/isre.2019.0916

60. Brown WO, Helland E, Smith JK. Corporate philanthropic practices. J Corp Financ. 2006;12(5):855–877. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2006.02.001

61. Zhu B. The self-centred philanthropist: family involvement and corporate social responsibility in private enterprises. Sociol Stud. 2015;30(2):74–97+243. doi:10.1186/s40711-021-00157-8

62. Wang XL, Fan G, Hu LP. Marketization Index of China’s Provinces: NERI Report 2019. Bei Jing: Social Science Academic Press; 2019.

63. Chen KJ. Media Supervision, Rule of Law and Earnings Management of Listed Companies. Manage Rev. 2017;29(7):3–18. doi:10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2017.07.001

64. Hong JK, Lee JH, Roh T. The effects of CEO narcissism on corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility. Manag Decis Econ. 2022;43(6):1926–1940. doi:10.1002/mde.3500

65. Yang H, Shi X, Wang S. Moderating effect of chief executive officer narcissism in the relationship between corporate social responsibility and green technology innovation. Front Psychol. 2021;12:717491. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.717491

66. Tang Y, Mack DZ, Chen G. The differential effects of CEO narcissism and hubris on corporate social responsibility. Strategic Manage J. 2018;39(5):1370–1387. doi:10.1002/smj.2761

67. Ahn JS, Assaf AG, Josiassen A, et al. Narcissistic CEOs and corporate social responsibility: does the role of an outside board of directors matter? Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;85:102350. doi:10.1002/smj.2761

68. Bouzouitina A, Khaireddine M, Jarboui A. Do CEO overconfidence and narcissism affect corporate social responsibility in the UK listed companies? The moderating role of corporate governance. Soc Bus Rev. 2021;16(2):156–183. doi:10.1108/SBR-07-2020-0091

69. Clayton P, Feldman M, Lowe N. Behind the scenes: intermediary organizations that facilitate science commercialization through entrepreneurship. Acad Manage Perspect. 2018;32(1):104–124. doi:10.5465/amp.2016.0133

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.