Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 16

How Nurses’ Person-Organization Fit Influences Organizational Loyalty

Received 6 July 2023

Accepted for publication 17 September 2023

Published 29 September 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2019—2036

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S425025

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Gulsum Kubra Kaya

Miaomiao Sun,1,2 Fahad Alam,3 Cunxiao Ma4

1School of Ethnology and Historiography, Ningxia University, Yinchuan, People’s Republic of China; 2The Party School of the CPC, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Party Committee, Ningxia Administration Institute, Yinchuan, People’s Republic of China; 3School of Economics and Management, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 4School of Marxism, Shandong Yingcai University, Jinan, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Fahad Alam, School of Economics and Management, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, Email [email protected]

Background: High turnover rates among nurses are a global concern due to the shortage of skilled professionals and increasing demand for high-quality healthcare. This study aims to enhance understanding of organizational fit by examining the impact of Person-organization fit (P-O fit) on organizational loyalty through the mediating role of organizational support and service quality, and the moderating impact of role ambiguity.

Methods: Using a convenience sampling technique, we employed a survey methodology by developing a questionnaire. Data were collected from a sample of 614 nurses in five different healthcare sectors in China. Employing SmartPLS 3.3, we conducted a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis to examine the relationships among the specified variables.

Results: The findings of the structural analysis suggest that the P-O fit influences organizational loyalty in the healthcare sector. Organizational support and service quality were identified as partial mediators of the P-O fit-organizational loyalty link. Additionally, the role of ambiguity represented a negative moderating impact between service quality and organizational loyalty.

Discussion: Overall, the study’s findings extend the understanding of person-organization fit, organizational support, service quality, role ambiguity, and organizational loyalty in the context of healthcare sectors and offer implications for medical authorities. Discussions, limitations, practical implications, and suggestions for further research are also provided.

Keywords: person-organization fit, organizational support, service quality, role ambiguity, organizational loyalty

Introduction

The rapid challenges and enormous work environment stress have put nurses under high psychological pressure. The current COVID-19 crisis accelerates these challenges in the healthcare sector. Evidence from 1257 samples reported symptoms of anxiety, depression, stress, and burnout by 44.6%, 50.4%, 71.5%, and 34.0% among healthcare personnel.1 Similar findings were explicitly reported in developing countries (see Table 1). In line with the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s economy has suffered in various sectors, including healthcare. The country’s healthcare system has been overwhelmed by the increase in cases of COVID-19,2 which has put a strain on front-line nurses, who are at risk of contracting the virus. In China, nurses have experienced both physical and psychological stress, including a high risk of infection, weariness, lack of family contact, and lack of skills.3 This severity caused additional mental health problems, which not only affect workers’ decision-making ability but could also have a long-term detrimental effect on their overall well-being, job performance, and organizational loyalty.4 The global turnout rate among nurses significantly from 18.7% to 27.1% in 2020.5 In the context of China’s healthcare sectors, nurses’ turnout intentions are widely high compared to other developed countries,3 which directly indicates low organizational loyalty.

|

Table 1 Nurses’ Psychological Problems |

The term good fit has become an essential and prevalent approach practiced by organizations for their rapid development and prosperity. Employees have an impact, and hiring the best person for the precise work task in the right organization can contribute to progressive work results.9 Many scholars believe that individuals whose values and personality traits align better with the objectives and goals of their organizations can display high organizational commitment.10 Since organizational loyalty is purely related to employee work behaviors that are not expected of nurses in their formal job descriptions and responsibilities,11 therefore, the influence of person-organization fit (P-O fit) on organizational loyalty is worth exploring. However, limited scientific evidence has been explored supporting the link between individual characteristics and organizational goals on organizational loyalty among nurses. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no research has investigated the impact of P-O fit on organizational loyalty in the healthcare context in China. Kristof-Brown (2000) defined P-O fit as an alignment of employee personality traits, knowledge, and skills with the demands of a specific task.12 P-O fit increases employee confidence and takes actions that favorably contribute to organizational development.13

Previous research suggests that the P-O fit is a significant construct that provides a potential foundation for positive work behavior,14 but its mere existence does not guarantee its high effectiveness. Accordingly, to understand how the P-O fit enhances organizational loyalty among nurses, Jaiswal and Dhar suggested that some influential factors deserve attention. Therefore, this research chose organizational support and service quality as powerful dynamics of healthcare sectors.15 Nurses who perceive support from their organization are more likely to engage in their work, have greater job satisfaction, and have low turnout.6 Nurses often work in a specific team, medical department, or organization; therefore, their cognition of OS is a significant antecedent.16 In addition, Alami et al have stated that organizational support helps contribute to discretionary behaviors such as stress management, overtime, and consistency in the nursing profession.17 Hence, incorporating organizational support with the P-O fit in healthcare sectors may influence nurses’ work engagement and loyalty.

Organizational loyalty among nurses is considered a decisive factor as it affects many aspects of healthcare care delivery (eg, high-quality care)18 and beyond significant outcomes;19 therefore, managers must focus on service quality among nurses to strengthen the link between job fit and organizational loyalty.18 In the healthcare context, service quality has positively impacted organizational loyalty among nurses. For example, a study by Abdullah et al found that service quality dimensions, such as empathy, reliability, and responsiveness, were positively related to organizational loyalty among nurses.18 Similarly, Suhail and Srinivasulu found that service quality had a significant positive impact on organizational loyalty among nurses.20 Here, it is worth considering the role of service quality and organizational support in the healthcare sectors in China.

Furthermore, this study considered role ambiguity a crucial stress factor in the healthcare industry. Cenzig et al defined role ambiguity as a lack of information and clarity on the job task and responsibilities associated with the position.21 Recently, Alblihed and Alzghaibi conducted a study in Saudi Arabia that revealed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses experienced high role ambiguity, which was significantly associated with an increased intention to quit their job.22 Nurses’ job tasks and responsibilities have risen and become more complicated, leading to an unclear and confusing situation in healthcare sectors. The lack of job roles can adversely affect the quality of service in the nursing profession.23 Furthermore, Chênevert et al highlighted that role ambiguity creates delusion, disappointment, and psychological withdrawal from quality services, which negatively affect job performance and cause high turnout.24 Therefore, role ambiguity is considered one of the destructive indicators of organizational loyalty.23

The healthcare sector in China has started to invest enormous resources in different technologies to increase the accuracy of patient care and performance.3 However, the construct of P-O fit has been neglected. A few pieces of research have analyzed the effect of technology on job performance and some of them analyzed the relationship between technology and patient care and satisfaction. However, the study gap remains; the P-T fit on organizational loyalty along with the mediating role of organizational support and service quality. In addition, it incorporates the moderating impact of role ambiguity between service quality and organizational loyalty.

Source: Developed by Authors

The organized structure of this paper is as follows: the introduction and theoretical background are covered in the first section. The second part addresses a theoretical framework and hypothesis development, and the next section explains the research methodology. Finally, the last section provides data analysis, results, research contribution, limitations, and future direction.

Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

Person-Organization fit, also known as value congruence, is a degree of perceived alignment between an individual’s values and the values advocated by their potential employer within the workplace.25 When employees’ traits and values are consistent with organizational goals, their work behavior and attitude will be favorably impacted.26 Scholars and practitioners are paying close attention to understanding the implications of fit theory on employee work behavior and organizational commitment.27 The fit perception between work behavior and organizational loyalty was explained by Lewin’s field theory, which states that “the person and organization must be viewed as a single constellation of interrelated components to comprehend or predict behavior”.25 This suggests that positive work attitudes, such as organizational commitment, are encountered when employees perceive their organization positively. When a P-O fit exists, the employee feels more committed to the job task and loyal to the organization.13 This perception has been confirmed and extended by several empirical studies in the context of healthcare sectors. Yan et al found that the P-O fit significantly influences job satisfaction.19 The P-O fit is found to be a predictor of positive outcomes such as quality performance, service quality, creative behavior, and less absenteeism.28

This study addresses a gap in the literature on healthcare sectors by applying fit theory (Bui et al) to understand better how P-O fit affects nurses’ work commitment.27 This study seeks to define the underlying engagement mechanisms by utilizing the construct of a P-O fit in fit theory. In the context of this theory, Bakker and Demerouti explain that job fit and organization demands are the two indicators directly linked with employee psychology and work behavior.29 Furthermore, Chênevert et al revealed that a lack of work fit could lead to ambiguity, dissatisfaction, burnout, work conflicts, and deterioration in employee health.24 Relevant empirical research indicates that in the context of nurses, the P-O fit is associated with their emotional behavior toward work attitude.29–31 They found a statistically significant inverse correlation between the P-O fit and the turnover rate. Recent organizational literature explored that job fit and organizational loyalty can be enhanced by other constructs, such as organizational support and service quality,14 particularly in healthcare sectors. In a quantitative review of the healthcare sector, Dirican and Erdil suggested that organizational support in medical occupations acts as a mediator in the relationship between P-O fit and organizational loyalty.32 This insight has been further extended by Abdullah et al, who claimed that service quality constructs among nurses can increase their organizational efficiency, which in turn enhances their job fit traits and work engagement.18 Therefore, according to these arguments, the theoretical framework of this study has been extended by adding organizational support and service quality construct to measure the mediating impact between P-O fit and organizational loyalty among nurses.

Moreover, the most critical concern is the moderating role of role ambiguity on the relationship between service quality and organizational loyalty. Role theory (Solomon et al) suggests that service quality aligns with role congruence, while incongruity triggers issues.33 In healthcare, nurses face service quality demands beyond their capabilities,21 leading to role ambiguity and turnover intentions.34 Kim and Byon reported that role ambiguity is associated with psychological extraction, such as job dissatisfaction and low organizational loyalty; however, it negatively influences prosocial behaviors.35 Therefore, based on the prior literature, the impact of the role ambiguity construct has been considered to analyze its moderating impact between service quality and organizational loyalty. Figure 1 represents the theoretical model of this study.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical framework. |

The Relationship Between P-O Fit and Nurses’ Loyalty

The P-O P-O fit has been categorized in various directions, such as goal congruence, value congruence, matching an employee’s needs and available resources in the workplace, and the best fit between individual personalities to the traits of the organization.36 According to the research, organizations and employees with good fit are more successful and competitive. The P-O fit between employees and the organization significantly affects work-attitude outcomes, such as low work stress, low turnout intention, psychological satisfaction, organizational commitment, work performance, and organizational loyalty.37

Seong and Choi argued that the P-O fit becomes high when the individual’s perspectives, values, norms, goals, traits, knowledge, and skills match with organizational resources, culture, standards, and task-related needs.38 Moreover, Dhir and Dutta claimed that the P-O fit is generated when the required resources are available to address employees’ demands, which enhances collaborative cooperation.39 An excellent organizational fit results in high employee adaptability, job participation, and accurate results with high performance, and therefore, organizational loyalty increases.38 Nolan and Morley tested the P-O fit theory in the healthcare sector, revealing that the organization fit concept helps medical employees adapt to stressful environments more efficiently.40

Employees with a good match for the P-O fit are content with their work and intrinsically inspired, consequently displaying a loyal attitude more consistently,28 Specifically, in healthcare sectors, where nurses face high levels of psychological stress. For instance, Cha et al analyzed Korean healthcare nurses, revealing that alignment between nurses’ traits and organizational needs predicts positive work behavior and loyalty.41 Yan et al indicated that P-O fit molded nurses’ turnout decisions either to stay in or quit a job.19 A good match of the P-O fit generates a strong favorable impact on the workplace environment, leading to innovative behavior in healthcare sectors. 11 Nurses intend to remain in the healthcare sector once their personality traits parallel organizational objectives.19

Previous research points out that the P-O fit can meet individual preferences and ultimate needs,14 which encourages positive feelings and work behavior among nurses, such as innovative behavior, commitment, and organizational loyalty. Consequently, it supports nurses in executing their tasks appropriately based on organizational needs.9 Lu et al implemented the organization fit theory in their study, which suggested that individuals exhibit high work engagement, intriguing, and energetic at work when their personality traits meet with the organizations.26 Similarly, Huang et al revealed that greater organizational fit reduces work stress,42 diminishes role ambiguity,9 decreases turnout rate,37 and increases job satisfaction in healthcare sectors.42 Therefore, based on the above arguments, it is hypothesized that:

H1: The person-organization fit shows a positive impact on organizational loyalty among nurses.

Mediating Role of Service Quality

In the healthcare industry, organizations prioritize the quality of the services that nurses offer patients because they play an integral role in job satisfaction, leading to organizational loyalty.43 In the healthcare sector, organizational loyalty is necessary to provide quality services to patients consistently.;41 although service quality is likely to play an influential role between good job fit and organizational commitment.43 Gutierrez et al surveyed 1030 nursing faculty in the USA to explore the effect of service quality and work values between the P-O fit and organizational loyalty.44 They found that well-equipped nursing faculty develop a strong bond with their organization, which can increase job performance, effectiveness, satisfaction, and organizational loyalty. Risman et al found that nurses’ quality was highly dependent on origination fit and organizational loyalty, indicating that nurses who deliver higher quality services are more loyal to their organization.25

The Grönroos service quality model covered three dominant dimensions: technical skills, functional quality, and psychological image. That model suggested the direct link of service quality between job fit and organizational function. Consequently, the model indicated that service quality could enhance organizational loyalty.45 Furthermore, low service quality can severely damage organizational loyalty. In healthcare, nurses offering high-quality services can achieve their goals more efficiently and successfully.18 A similar perspective was stated by Cha et al arguing that P-O fit and organizational behavior, such as quality service and loyalty, are correlated in the healthcare sectors.41 They highlighted that poor services are linked with the misfits of organizations that cause a high turn overrate.31 In other words, nurses with quality service are more likely to be favorable when their personal characteristics match the organizational goal, and consequently, it increases their organizational commitment.31,41

Service quality has been found to mediate between P-O fit and organizational loyalty.9,26 According to the theory of social exchange, fit and organization loyalty can be improved when employees believe that their quality of service can meet the organizational values and goals, which are more closely aligned.46 Nurses who provide high-quality service would feel obligated and would focus more on organizational goals. Given the above, it is proposed that:

H2: SQ mediates the relationship between P-O fit and organizational loyalty.

The Mediating Role of Organizational Support

The social exchange theory explains how P-O fit affects loyalty via organizational support. Based on this theory, individuals feel compelled to contribute more to the organization than expected in their job roles due to goodwill and organizational support for employees. Therefore, Employees are more likely to participate in the organization because of organizational support, and employees will consider each other’s needs when necessary.47 Employees display high levels of loyalty to the organization when they identify their traits and ambitions to fit their organization’s values. They believe that organizational support can improve their values and beliefs, leading them to a high level of commitment.9 Moreover, employees are more likely to initiate innovative ideas, discover possible opportunities, problem-solving skills, providing authentic feedback about their job tasks when they perceive their organization cares about them,48 specifically in the healthcare sector.

Employees can understand the organization’s treatment of them favorably or unfavorably as a sign of how much the organization values their contributions and is concerned with their well-being.49 Following social exchange theory, fair treatment and value from employers lead to increased employee emotional attachment, commitment, and heightened engagement in the organization. When employees perceive fit in the organization, they observe a high level of organizational support. In the healthcare sector, organizational support encourages nurses at work, creating a reciprocal relationship that contributes to the organization’s success by getting people to adopt new ideas.32 Gupta elaborated on organizational support theory; When employees believe their employer will care for them in times of need, they show more enthusiasm and put more effort into accomplishing their job tasks.30 Similarly, in the provision of this notion, Modaresnezhad et al surveyed Indonesian healthcare nurses, revealing that strong organizational support fosters commitment to tasks, and loyalty emerges when nurses’ traits align with the organization’s goals.50 An organization’s ability to stick employees devoted to achieving organizational goals also varies on the degree of P-O fit,19 which can be enhanced by high organizational support.50

Ultimately, strong organizational support helps nurses cope with stress, reducing anxiety. Consequently, organizational support factors are predicted to help nurses’ enduring commitment to the organization, and are likely to increase the link between job fit and organizational loyalty.13 Therefore, based on the above literature, it has been postulated:

H3: OS mediates the relationship between P-O fit and organizational loyalty.

The Moderating Position of Role Ambiguity

Previous studies investigated factors (eg work stress, poor leadership, and organizational conflicts) that may cause a high turnover rate among nurses.51 Role ambiguity is one of the critical factors among them that lead nurses to quit their job. McCauley et al stated that nurses experience fatigue, exhaustion, and depression in a workplace environment.52 As a result, there is role ambiguity, which directly impacts their overall performance. Task awareness in nursing practice plays an important role in determining organizational and employee outcomes of distress, job satisfaction, and organizational loyalty.53 Nurses who face ambiguity in their role show a lack of service quality and organizational loyalty.54 Furthermore, role ambiguity can lead to work burnout, causing physical and psychological strain, reduced commitment, and service quality.53

The moderating impact of role ambiguity among nurses is destructive, such as psychological stress, low self-esteem, or dysfunction in dealing with others;5 Consequently, it reduces the level of service quality and satisfaction among nurses. Cengiz et al endorsed this assertion; they revealed that role ambiguity was adversely correlated with nurses’ willingness to show work behavior that contributes to the well-being of the healthcare organization.21 According to Yu et al, in the present era, assigning additional roles is a frequent practice in healthcare sectors which is directly linked with role ambiguity.55 This implies that when employees are vague about their expected tasks, they exert less effort, significantly affecting their service quality and work commitment.21 Previous studies have attempted to understand employee service quality associated with organizational commitment.5 This presumes job roles have related factors that affect employee work attitudes, such as definite job roles. In healthcare sectors, clear job roles are a significant predictor that improves service quality and diminishes work conflict, associated with positive outcomes for the organization.21,24 However, unclear roles have a strong moderating impact on service quality and organizational loyalty.

Yu et al examined how nurses react when they experience unclear job tasks, highlighting that erroneous job information results in non-serious behaviors like absenteeism, tardiness, low effort, and high turnover.55 Additionally, role ambiguity is characterized by a lack of clear direction for a person’s job role within the organization.56 A lack of knowledge or inadequate information causes ambiguity. Hoboubi et al noticed that insufficient training, ineffective communication, or the distortion of information by a peer, supervisor, or employer could cause role ambiguity, which significantly affects their service quality and organizational goals.56,57 In line with the prior theoretical job-demand and resources model, it is suggested that role ambiguity breaks the social bond among employees and decreases work engagement.28 Orgambídez et al revealed that role ambiguity moderated the impacts of employee contribution from favorable to unfavorable outcomes, specifically in healthcare sectors.58 Nurses always face additional challenges due to work overload, uncertain situations, and high psychological and emotional stress. Due to this, their overall service quality significantly decreases, and that causes low organizational loyalty among them. On the basis of the above arguments, propose the following hypothesis:

H4: RE will moderate the relationship between service quality and organizational loyalty among nurses.

Research Methodology

Pilot Study

A pilot study was conducted to evaluate the factor in a condensed version of the 10-item developed by Cable and DeRue, to obtain an adequate measure of the P-O fit.59 On a scale from 1 to 5 (strongly disagree-strongly agree), participants indicated their limitations with each statement. The three primary dimensions of P-O fit include job fit, organizational value, and personality traits. The fit was measured with four items applicable to knowledge, skills, and ability within the organization’s criteria, such as whether my skills and abilities match my job obligations. Organizational value was considered with three items regarding job tasks, eg, employee knowledge significantly meets the criteria of organizational objectives. Three elements were used to evaluate personality traits relevant to the level of awareness in the organization, including emotional intelligence, conflict management, and enthusiasm, such as “I display positive emotions when I perform my job task.” The questionnaire was completed by 117 nurses from five hospitals in China to confirm the factor structure of this condensed version. SPSS 20.1 results for exploratory factor analysis revealed the anticipated three-factor solution. However, two items did not meet the fit criteria and were eliminated. An element of organizational value was removed because it did not load onto its relevant factor. The other item was eliminated from the personality traits because it did not display an acceptable loading of (0.50).

Sample Design and Data Collection

Data were collected from nurses and their supervisors from five health sectors in two provinces in China. The researcher asked permission from the head of the healthcare department to discuss the research topic and an appropriate procedure to collect the data before distributing the surveys. The primary goal, made clear to managers, was to gather the thoughts, perceptions, and beliefs of nurses and their leaders. It was decided that the scholar would have contact with the healthcare departments to distribute the questionnaire, and the data would be kept private.

Using a convenience sampling technique, we employed a survey methodology by developing a questionnaire. This method was used due to its established credibility and reliable research technique commonly used by scholars. This method is appropriate when obtaining a complete sampling frame. This sampling approach is well-suited for enabling theoretical generalization of the outcomes. The questionnaire survey method is cost-effective and suitable for contacting small and large groups, allowing the quick collection of data samples for statistical analysis.60 Only on-duty nurses willing to participate in the research were approached. A total of 650 nurses (130 in each of the five hospitals selected) received the questionnaire, which included the measurements of P-O fit, OS, SQ, RA, and OL. The survey was distributed by three research assistants to nurses and their supervisors, respectively. Participants were requested to deliver their questionnaire feedback at a receptionist counter, where the research assistants would collect it after four weeks.

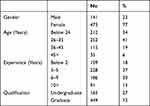

In total, 621 feedbacks were returned; 614 were judged suitable, 141 were male (23%), and 473 were female (77%) for additional analytical processes after the incomplete questionnaires were discarded. Furthermore, the average age was 22.87, with a standard deviation of 0.402. Moreover, the absolute minimum sample size determined by Westland’s statistical software technique is 250 cases, which is the lower constraint for the sample size for the SEM model.61 Therefore, with 614 participants, our study meets the standard sample size for sampling acceptability.61 The demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Respondent’s Profile |

Measures

The study instrument consisted of 37 items split into five construct categories that examined P-O fit, organizational support, service quality, role ambiguity, and organizational loyalty. The scales used to measure each variable were adapted from previous studies and modified to align with the specific context of the present study. The overall construct comprised in this research was assessed by multiple items drawn from previous studies. This method was employed because multiple-item measures might be more reflective of and connected to the constructs compared with a single item.62 The target participants were asked to rate how much they agreed and disagreed with the statement. The language of instruction was Urdu and English, followed by standard protocols. The questionnaire was based on a Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

Organizational Support

A six-item scale was adapted from (Rhoades et al) study and modified to fit the specific context of our study to assess organizational support.63 Sample items: “The things that I value in life are very similar to the things that my organization values.” The value of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.847.

Service Quality

Service quality was measured with a six-item scale adopted by (Sjetne et al)64 The item scales were slightly changed to fit our study perceptions. The factor loadings for each item are given in Table 3, together with the AVE. Nurses were asked to score, on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 strongly disagree, to 5 strongly agree), how much they agree or disagree with the effect of service quality on organizational behavior. Service quality had a Cronbach alpha value of 0.921.

|

Table 3 Validity and Reliability |

Role Ambiguity Scale

Chang and Hancock scale, consisting of seven items, was used to measure the level of how well nurses understand their goals, obligations, and the degree of vagueness in their job instructions (ie, “I need to skip some rules to do the assigned tasks”).65 The role ambiguity of the Cronbach alpha value was 0.846.

Organizational Loyalty

Measurements of organizational loyalty were taken from a previous study (Yoon & Suh Wu).46 The seven-item scales adopted were slightly modified according to the present study. The items scale includes “I really care about the fate of this hospital.” The value of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.872.

Data Analysis and Results

Adhering to the two-stage analytical techniques, we used SPSS 20 to examine the measurement model to investigate the questionnaires’ validity and reliability. Subsequently, we run the structural model by using SmartPLS 3.3 to analyze the relationships between the targeted variables.66

Common Method Bias (CMB)

Common method bias should be tested when data samples are collected through questionnaires and, specifically, when independent and dependent variables are collected from the same respondents.67 Harman’s single-factor test was adopted to check the common method bias. The test explained 37.628% of the variance, suggesting that it falls under the threshold criteria of 50%. Consequently, there is no method bias issue in this research.

Measurement Model

Initially, the convergence validity of the measurement model was examined. This was measured by factor loadings, Composite Reliability, and average variance extracted. All scale loadings meet the criteria of 0.6,68 as shown in Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha α and CR values exceeded the 0.70 thresholds, indicating that all study constructs showed internal consistency. Similarly, AVE and CR were higher than the recommended criteria of 0.5 and 0.7, respectively, as given in Table 3. Table 4 demonstrates that every construct’s square root of the Average Variance Extracted exceeds its intercorrelations with other constructs.69 However, the Fornell and Larcker criteria have recently been criticized, with some claims that they cannot consistently identify the lack of discriminant validity in typical research scenarios.70 Consequently, the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations, proposed by Henseler et al,70 is an alternate method and was considered to assess the discriminant validity, as shown in Table 5. The findings revealed a positive correlation between the P-O fit and OL (0.559, 0.000). Similarly, the correlation analysis between OS and OL (0.670, P= 0.000) and SQ and OL (0.620, P= 0.001) shows a significant positive relationship. The ambiguity of the role shows a negative correlation with OL (−0.23, p=0.001).

|

Table 4 Discriminant Validity |

|

Table 5 Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) |

Structural Model

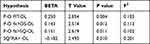

First, we looked at how much of the variance in the different outcome variables was explained by the independent variable. Organizational loyalty was expected by the P-O fit, organizational support and service quality, while role ambiguity predicted its significant influence on organizational loyalty; together, these variables explained 45.4% of the variance in organizational loyalty (R2= 0.454). This can be described as moderate.68 Cohen recommends that an R2 value greater than 0.26 demonstrates a substantial model.71 Then we evaluated effect sizes (f2). The p-value in the results indicates significance but does not indicate the size of an effect. Therefore, it is necessary to report both substantive significance (f2) and statistical significance (p). Cohen’s recommended criteria were considered to assess the effect size, which indicates 0.02 for weak, 0.15 for medium, and 0.35 for large effects.71 The results revealed that there is a medium effect, as given in Table 6. A Q2 illustrates how the fit of the data can be empirically reconstructed using the research model and the PLS parameters based on the blindfolding technique. Cross-validated redundancy methodologies were used to determine Q2 for this investigation. If Q2 is greater than 0, the model is predictively relevant; however, Q2 less than 0 indicates that the model is not predictively relevant. Figure 2 shows adequate predictive relevance.

|

Table 6 Structural Estimates |

|

Figure 2 Structural Model. |

We used a bootstrapping approach with 5000 samples to analyze R2, beta (β), and the accompanying t-values to analyze the direct and indirect relationship between the fit and organizational loyalty, organizational support, service quality, and role ambiguity.66 The research involved five variables in general. The predictor variable was P O fit; organizational support and service quality were mediating variables, and the outcome variable was organizational loyalty. At the same time, the ambiguity of the role shows the moderating impact between service quality and organizational loyalty. Initially, we ran the direct effect to examine the hypothesis that measures the P-O fit impact on organizational loyalty. Subsequently, the indirect impact was observed to determine whether organizational support and service quality mediate the relationship between OP fit and organizational loyalty. Finally, we run the moderating impact of role ambiguity between service quality and organizational support (Figure 2).

Direct Effects

The findings revealed that the P O fit shows a significant positive relationship with organizational loyalty (β = 0.251, t = 2.854, p < 0.004), indicating that a higher P O fit can increase work commitment and lead to organizational loyalty among nurses in healthcare sectors. Therefore, H1 is accepted.

Indirect Effects

The mediating variable shows a significant relationship between P-O fit and organizational loyalty. The results show a partially mediating effect of organizational support between the independent variable and the dependent variable (β = 0.143, t = 2.514, p = 0.012) and a partially mediating effect of service quality between the independent variable and the dependent variable (β = 0.151, t = 2.619, p = 0.011), suggesting that a strong perception of organizational support and service quality was linked with increased organizational loyalty. Consequently, H2 and H3 were accepted.

Moderating Effect

This research hypothesized that role ambiguity moderates the relationship between service quality and organizational loyalty. Using the PLS product indicator technique, moderation analysis is evaluated. According to Chin et al, by considering the inaccuracy that weakens the estimated correlations and enhances the validity of theories,68 PLS can provide more precise estimates of moderator effects.70 The results provide a significant negative moderating impact of role ambiguity between service quality and organizational loyalty (β = −0.182, t = 2.493, p = 0.010), as shown in Table 6. Therefore, the study accepted H4.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study aimed to identify the factors that contribute to increased organizational loyalty among nurses in the healthcare sector in China. The study was conducted due to concerns about the negative impact of psychological stress in healthcare work environments due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to understand the relationship between an individual nurse’s values and traits (P-O fit) and their level of organizational loyalty.

The study used a conceptual framework of “fit theory” to examine the relationship between P-O fit and organizational loyalty, the role of organizational support and service quality as a mediating variable and the impact of role ambiguity as a moderator variable.

The findings of this study suggest that the P-O fit directly affects organizational loyalty. Specifically, when nurses believe that their values and traits align with those of the organization, they are more likely to be devoted to their job tasks. However, regarding P-O fit, there is a critical disconnect between organizational research and practice, as practitioners persistently believe that fit is crucial for evaluating employee success, yet the results from past research have demonstrated mixed or weak effects.12

This study does not intend to contradict the previous argument; however, it provides a constructive perspective that reinforces the substantial impact of the P-O fit depending on organizational nature. For example, a study by Yan et al found that nurses who felt a strong P-O fit were likelier to have a positive attitude toward their organization.19 Another study by Jehanzeb and Naz et al found a positive correlation between P-O fit and organizational commitment among nurses.13,14 The findings are consistent with Risman et al, who showed that a strong P-O fit can reduce role ambiguity and conflict.25 When nurses clearly understand their role within the organization and how their work contributes to the larger goals, they are more likely to develop a high level of organizational commitment. Our discussion supports previous research by highlighting the importance of this relationship and the key aspects that contribute to it. This information may be useful for healthcare organizations looking to improve employee retention and satisfaction among their nursing staff.

The finding provides a significant perspective and sheds light on the importance of considering the fit between the individual and the organization in healthcare care. Highlighting the P-O fit perspective is important because it moves beyond the traditional focus on factors such as job duties and salary to include the intangible aspects of work, such as the fit between the individual and the organization. Healthcare organizations can create a supportive and fulfilling work environment by considering the fit between individual values and organizational goals. By emphasizing shared values and goals, organizations can promote employee engagement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment among nurses. This can lead to a more motivated, productive workforce committed to delivering high-quality care. In turn, this can result in better patient outcomes and a stronger reputation for the organization.

Second, the hypothesis is tested to analyze whether the perceptions of organizational support and service quality predicted the relationship between P-O fit and organizational loyalty. The findings satisfy our expectations about the mediating effect on organizational loyalty. This finding proposes that nurses’ positive assessments about the extent of OS they receive drive them to remain in the organization. Based on the P-O fit theory,72 these findings highlight that nurses respond to high job commitment when they perceive strong OS. The literature has revealed that employees with high organizational support tend to react to the organization in several favorable ways.73 Our findings proved this argument and precisely indicated organizational loyalty as a favorable repayment.

Moreover, Dirican and Erdil’s study has highlighted that social support may positively or indirectly impact employee work behavior.32 They argued that the support obtained from colleagues or peers is more significant compared to the organizations’ support. Evidence from Jehanzeb validated this argument that when employees perceive that their organization supports them, they are more likely to develop a sense of loyalty and commitment to the organization.14 In other words, the impact of P-O fit on employee loyalty may be strengthened or weakened depending on the level of organizational support perceived by the employee. However, our results emphasize the significance of OS in the relationship between P-O fit and organizational loyalty.

The findings showed that service quality partially mediates the relationship between P-O fit and organizational loyalty. Our study results are consistent with Abdullah et al study, which found that when nurses perceive a strong fit between themselves and their organization, they are more likely to provide high-quality services to patients, which can lead to greater organizational commitment and loyalty.18 This implies that the impact of the P-O fit on organizational loyalty is indirect and can be strengthened if combined with high levels of service quality. One possible explanation for these findings is that when employees, such as nurses, experience a good IO fit with their organization, they are more likely to be satisfied with their work environment. High-quality service can further enhance this satisfaction, leading to greater commitment to work and, ultimately, higher levels of organizational loyalty.

Hence, this research covers the most critical research gap in healthcare by considering service quality and its mediating impact on nurse organizational loyalty. Furthermore, it is important to consider nurses’ work attitudes as part of any conceptual model while studying the behavior of nurses work, particularly in the service sector. These findings indicated that organizational loyalty has a link with service quality. It is important to note that other factors can also enhance nurses’ work behavior. For example, Fernandes and Rinaldo showed that the relationship between P-O fit and work commitment was mediated by behavioral loyalty.74 Similarly, previous research in the service sector focused on other mediating factors such as well-being, knowledge-sharing behavior, and emotional intelligence to evaluate the nurses’ work behavior and attitude of nurses toward the organization, which shows interesting results concerning individual work behavior.11 Our findings acknowledge the importance of SQ and suggest that it is essential to build strong mechanisms in the healthcare sectors that can analyze, measure, and improve SQ among nurses, as their work pressure is enormous compared to other professions.

Finally, this research contributes to the literature by assessing role ambiguity as a moderating variable that may affect the relationship between service quality and organizational loyalty. Our findings confirm that role ambiguity has a negative moderating impact on loyalty among nurses. The results indicate that unclear job tasks have a destructive impact on nurses’ well-being and job satisfaction. When nurses have little information or a lack of knowledge to perform their jobs, it may lead to a work conflict, resulting in increased turnout intentions. This highlights the importance of clarifying job roles and responsibilities to foster organizational loyalty among nurses.

Previous research findings suggest that the detrimental effect of role ambiguity on employee loyalty can be mitigated by the level of support provided by the leader.75 More studies are needed to explore the exact nature of this relationship and to determine the specific types of supportive behaviors that are most effective in buffering against the negative effects of role ambiguity. A recent study by Ahmad et al endorsed that role ambiguity creates a bullying work environment and positively correlates with psychological stress. This means that employees who experience role stress are more prone to exhibit undesirable behavior and to be dissatisfied with their work.

This study contributes significantly to the existing body of research on organizational loyalty by examining the relationships between P-O fit, OS, SQ, and RA within the China healthcare sector, focusing on front-line nurses working in hospitals during an emergency. This study provides empirical evidence of the impact of stress on organizational loyalty in a highly stressful and challenging environment.

Implications

Theoretical Implication

The organizational fit for nursing is an efficient strategy to nurture organizational commitment. This study explored the impact of the P-O fit on organizational loyalty among nurses and the mediating role of organizational support and service quality. Additionally, this study introduced ambiguity in the role as a significant moderator of the relationship between service quality and organizational loyalty. The results revealed a positive link between OP fit and organizational loyalty, and organizational support and service quality show a partial mediation effect between the dependent and independent variables. The findings support the concept that the fit theory in the healthcare sector adds value to nurses and is connected to positive insights into job satisfaction, work commitment, and organizational loyalty. In addition, the P-O Fit Theory suggests that alignment between nurses’ individual characteristics and the organizational culture leads to increased job satisfaction, commitment, and loyalty. Exploring this relationship can enhance our understanding of how organizations can better align their values with nurses’ needs, fostering greater loyalty and retention. Moreover, the Social Exchange Theory emphasizes the reciprocal nature of relationships, suggesting that when nurses perceive a positive fit within the organization, they are more likely to reciprocate with higher levels of loyalty and commitment. Healthcare organizations need to develop strategies to improve P-O fit, leading to increased organizational loyalty among nurses and ultimately enhancing patient care outcomes. The results indicated that organizational support and service quality provide advantages for nurses to display positive work behavior in a stressful work environment. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that role ambiguity has a destructive impact on organizational loyalty. Without a clear understanding of their role in their job, nurses were unable to perform their duties, which caused them to frequent absenteeism and loss of interest in their jobs.

Managerial Implications

Practically, healthcare administrators can use the P-O fit approach to design programs that identify potential candidates whose values and traits align with the organization’s values and goals, ultimately leading to better job fit and favorable outcomes. First, Organizations can focus on recruitment and selection practices that assess the alignment between nurses’ values and goals with the organizational culture. Secondly, fostering a positive and supportive organizational culture that promotes autonomy, recognition, and growth is crucial. Providing opportunities for professional development and training can contribute to nurses’ sense of personal and professional growth within the organization. Additionally, implementing initiatives that promote work-life balance, flexible scheduling, and supportive leadership can enhance nurses’ P-O fit and loyalty. It also focuses on developing its employees, ensuring that they align with the organization’s goals and values. This can lead to improved employee engagement, satisfaction, and retention, which in turn, enhance the quality of care provided to patients. Third, P-O fit tactics can help healthcare organizations create a positive reputation, leading to a greater ability to attract and retain the best candidates. By having a strong culture that values alignment with organizational goals and objectives, healthcare organizations can differentiate themselves from other organizations and attract top talent, ultimately leading to better outcomes for both the organization and its patients. The P-O fit approach can lead to a more efficient and effective recruitment and selection process. By focusing on critical factors such as personality, values, and work style, healthcare administrators can more accurately identify candidates that are a good fit for the organization, reducing the likelihood of high turnover rates and recruitment costs.

The study applies to all organizational sectors (eg, educational, banking, and industrial sectors), where employers seek more for their long-term organizational benefits.

Limitation and Future Direction

Like all research, the present study has a few limitations that could affect its generalizability and provide the potential for further research. First, the P-O fit is incorporated with three dimensions (job fit, organizational value, and personality traits). However, Risman et al recommended that P-O fit perceptions can be measured holistically.25

Second, this study targeted the healthcare sector in China, as behavioral theories suggest that employees’ work behavior depends on the nature of the job and organization. Therefore, future research could build on this study by taking a more comprehensive view of the other organizational environment.

Third, the participants were from five healthcare sectors in China, which operate under a one-tier structure, as opposed to the two-tier system found in many Western nations (eg the USA and the UK). Therefore, additional research is needed to evaluate whether the results can be applied to different healthcare sectors worldwide.

Fourth, this study was based solely on correlational data, which shows that the cause and effect cannot be determined. Consequently, an experimental approach will be required to support the claim that P-O fit will increase nurses’ organizational loyalty.

Finally, this study incorporated organizational support and service quality as a mediator variable and role ambiguity as a moderator variable. Future research may examine how P-O fit can enhance organizational loyalty by applying other relevant mediating and moderating variables such as knowledge-sharing behavior, emotional intelligence, and job embeddedness. This will provide more insight into how P-O fit influences work behavior.

Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Academic Development and Ethics Committee of the University of Science and Technology Beijing (Reference No. 202105/USTB/47) and conducted in line with the Helsinki Declaration principle. We used only standard procedures and measurement instruments. All respondents participated in the survey Willingly and voluntarily. A description of study objectives was given prior to the questionnaire. Those who were comfortable continued answering.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

2. Xiong L, Zhong BL, Cao X, et al. Possible posttraumatic stress disorder in Chinese front-line healthcare workers who survived COVID-19 6 months after the COVID-19 outbreak: prevalence, correlates, and symptoms. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1). doi:10.1038/s41398-021-01503-7

3. Yang Y, Chen J. Related factors of turnover intention among pediatric nurses in Mainland China: a Structural equation modeling analysis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;53:e217–e223. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2020.04.018

4. Shahrour G, Dardas LA. Acute stress disorder, coping self‐efficacy and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID‐19. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(7):1686–1695. doi:10.1111/jonm.13124

5. Poon YSR, Lin YP, Griffiths P, Yong KK, Seah B, Liaw SY. A global overview of healthcare workers’ turnover intention amid COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with future directions. Hum Resour Health. 2022;20(1). doi:10.1186/s12960-022-00764-7

6. Labrague LJ, De Los Santos JAA. COVID‐19 anxiety among front‐line nurses: predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(7):1653–1661. doi:10.1111/jonm.13121

7. Maqbali MA, Khadhuri JA. Psychological impact of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic on nurses. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2021. doi:10.1111/jjns.12417

8. Maqbali MA, Sinani MA, Al-Lenjawi B. Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2021;141:110343. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110343

9. Afsar B, Badir YF. Workplace spirituality, perceived organizational support and innovative work behavior. J Workplace Learn. 2017;29(2):95–109. doi:10.1108/jwl-11-2015-0086

10. Lau PYY, McLean GN, Hsu YC, Lien BYH. Learning organization, organizational culture, and affective commitment in Malaysia: a person–organization fit theory. Hum Resour Dev Int. 2016;20(2):159–179. doi:10.1080/13678868.2016.1246306

11. Afsar B. The impact of person-organization fit on innovative work behavior. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2016;29(2):104–122. doi:10.1108/ijhcqa-01-2015-0017

12. Kristof-Brown AL. Perceived applicant fit: distinguishing between recruiters’ perceptions of person-job and person-organization fit. Pers Psychol. 2000;53(3):643–671. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2000.tb00217.x

13. Naz S, Li C, Nisar QA, Khan MAS, Ahmad N, Anwar F. A study in the relationship between supportive work environment and employee retention: role of organizational commitment and person–organization fit as mediators. SAGE Open. 2020;10(2):215824402092469. doi:10.1177/2158244020924694

14. Jehanzeb K. Does perceived organizational support and employee development influence organizational citizenship behavior? Eur J Train Dev. 2020;44(6/7):637–657. doi:10.1108/ejtd-02-2020-0032

15. Jaiswal D, Dhar RL. Impact of perceived organizational support, psychological empowerment and leader member exchange on commitment and its subsequent impact on service quality. Int J Product Perform Manag. 2016;65(1):58–79. doi:10.1108/ijppm-03-2014-0043

16. Al-Hussami M, Hammad S, Alsoleihat F. The influence of leadership behavior, organizational commitment, organizational support, subjective career success on organizational readiness for change in healthcare organizations. Leadersh Health Serv. 2018;31(4):354–370. doi:10.1108/lhs-06-2017-0031

17. Alami H, Lehoux P, Denis JL, et al. Organizational readiness for artificial intelligence in health care: insights for decision-making and practice. J Health Organ Manag. 2020;35(1):106–114. doi:10.1108/jhom-03-2020-0074

18. Abdullah MI, Huang D, Sarfraz M, Sadiq MW. Service innovation in human resource management during COVID-19: a study to enhance employee loyalty using intrinsic rewards. Front Psychol. 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627659

19. Yan W, Wu X, Wang H, et al. Employability, organizational commitment and person–organization fit among nurses in China: a correctional cross‐sectional research. Nurs Open. 2022;10(1):316–327. doi:10.1002/nop2.1306

20. Suhail P, Srinivasulu Y. Perception of service quality, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions in Ayurveda healthcare. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2021;12(1):93–101. doi:10.1016/j.jaim.2020.10.011

21. Cengiz A, Yoder LH, Danesh V. A concept analysis of role ambiguity experienced by hospital nurses providing bedside nursing care. Nurs Health Sci. 2021;23(4):807–817. doi:10.1111/nhs.12888

22. Alblihed MA, Alzghaibi HA. The impact of job stress, role ambiguity and work–life imbalance on turnover intention during COVID-19: a case study of front-line health workers in Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(20):13132. doi:10.3390/ijerph192013132

23. Sureda E, Mancho J, Sesé A. Psychosocial risk factors, organizational conflict and job satisfaction in Health professionals: a SEM model. An Psicol. 2018;35(1):106–115. doi:10.6018/analesps.35.1.297711

24. Chênevert D, Kilroy S, Bosak J. The role of change readiness and colleague support in the role stressors and withdrawal behaviors relationship among health care employees. J Organ Change Manag. 2019;32(2):208–223. doi:10.1108/jocm-06-2018-0148

25. Risman KL, Erickson RJ, Diefendorff JM. The impact of person-organization fit on nurse job satisfaction and patient care quality. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;31:121–125. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2016.01.007

26. Lu ACC, Lu L. Drivers of hotel employee’s voice behavior: a moderated mediation model. Int J Hosp Mana. 2020. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102340

27. Bui HT, Zeng Y, Higgs M. The role of person-job fit in the relationship between transformational leadership and job engagement. J Manag Psychol. 2017;32(5):373–386. doi:10.1108/jmp-05-2016-0144

28. Peng JC, Lee YL, Tseng MM. Person-organization fit and turnover intention: exploring the mediating effect of work engagement and the moderating effect of demand-ability fit. J Nurs Res. 2014;22(1):1–11. doi:10.1097/jnr.0000000000000019

29. Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22(3):273–285. doi:10.1037/ocp0000056

30. Gupta V. Impact of perceived organisational support on organisational citizenship behaviour on health care and cure professionals. Manag Dyn. 2022;19(1):35–44. doi:10.57198/2583-4932.1027

31. Cao J, Zhao J, Zhu C, et al. Nurses’ turnover intention and associated factors in general hospitals in China: a cross‐sectional study. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(6):1613–1622. doi:10.1111/jonm.13295

32. Dirican AH, Erdil O. Linking abusive supervision to job embeddedness: the mediating role of perceived organizational support. Curr Psychol. 2020;41(2):990–1005. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-00716-1

33. Solomon MR, Surprenant C, Czepiel JA, Gutman E. A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: the service encounter. J Mark. 1985;49(1):99–111. doi:10.1177/002224298504900110

34. Alam T, Ullah Z, AlDhaen FS, AlDhaen E, Ahmad N, Scholz M. Towards explaining knowledge hiding through relationship conflict, frustration, and irritability: the case of public sector teaching hospitals. Sustainability. 2021;13(22):12598. doi:10.3390/su132212598

35. Kim K, Byon KK. Examining relationships among consumer participative behavior, employee role ambiguity, and employee citizenship behavior: the moderating role of employee self-efficacy. Eur Sport Manag Q. 2018;18(5):633–651. doi:10.1080/16184742.2018.1451906

36. Jehanzeb K, Mohanty J. Impact of employee development on job satisfaction and organizational commitment: person–organization fit as moderator. Int J Train Dev. 2018;22(3):171–191. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12127

37. Aman-Ullah A, Aziz A, Ibrahim H, Mehmood W, Abbas YA. The impact of job security, job satisfaction and job embeddedness on employee retention: an empirical investigation of Pakistan’s healthcare industry. J Asia Bus Stud. 2021;16(6):904–922. doi:10.1108/jabs-12-2020-0480

38. Seong JY, Choi JN. Is person–organization fit beneficial for employee creativity? Moderating roles of leader–member and team–member exchange quality. Hum Perform. 2019;32(3–4):129–144. doi:10.1080/08959285.2019.1639711

39. Dhir S, Dutta T. Linking supervisor-support, person-job fit and person-organization fit to company value. J Indian Bus Res. 2020;12(4):549–561. doi:10.1108/jibr-04-2019-0124

40. Nolan E, Morley MJ. A test of the relationship between person–environment fit and cross-cultural adjustment among self-initiated expatriates. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2013;25(11):1631–1649. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.845240

41. Cha J, Chang YK, Kim TY. Person–organization fit on prosocial identity: implications on employee outcomes. J Bus Ethics. 2014;123(1):57–69. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1799-7

42. Huang X, Wang L, Dong X, Li B, Wan Q. Effects of nursing work environment on work‐related outcomes among psychiatric nurses: a mediating model. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2020;28(2):186–196. doi:10.1111/jpm.12665

43. Lee SM, Lee D. Effects of healthcare quality management activities and sociotechnical systems on internal customer experience and organizational performance. Serv Bus. 2022;16(1):1–28. doi:10.1007/s11628-022-00478-9

44. Gutierrez AP, Candela L, Carver L. The structural relationships between organizational commitment, global job satisfaction, developmental experiences, work values, organizational support, and person-organization fit among nursing faculty. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(7):1601–1614. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05990.x

45. Kang GD, James J. Service quality dimensions: an examination of Grönroos’s service quality model. Manag Serv Qual. 2004;14(4):266–277. doi:10.1108/09604520410546806

46. Yoon MH, Suh J. Organizational citizenship behaviors and service quality as external effectiveness of contact employees. J Bus Res. 2003;56(8):597–611. doi:10.1016/s0148-2963(01)00290-9

47. Akgündüz Y, Sanli SC. The effect of employee advocacy and perceived organizational support on job embeddedness and turnover intention in hotels. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2017;31:118–125. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.12.002

48. Gregory BT, Albritton MD, Osmonbekov T. The mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relationships between P–O fit, job satisfaction, and in-role performance. J Bus Psychol. 2010;25(4):639–647. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9156-7

49. Chung YW. The role of person–organization fit and perceived organizational support in the relationship between workplace ostracism and behavioral outcomes. Aust J Manag. 2015;42(2):328–349. doi:10.1177/0312896215611190

50. Modaresnezhad M, Andrews MC, Mesmer-Magnus J, Viswesvaran C, Deshpande SP. Anxiety, job satisfaction, supervisor support and turnover intentions of mid‐career nurses: a structural equation model analysis. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(5):931–942. doi:10.1111/jonm.13229

51. Islam I, Alam KMW, Keramat SA, et al. Working conditions and occupational stress among nurses in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional pilot study. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2021;30(9):2211–2219. doi:10.1007/s10389-020-01415-8

52. McCauley L, Kirwan M, Riklikienė O, Hinno S. A SCOPING REVIEW: the role of the nurse manager as represented in the missed care literature. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(8):1770–1782. doi:10.1111/jonm.13011

53. Dawson A, Stasa H, Roche M, Homer C, Duffield C. Nursing churn and turnover in Australian hospitals: nurses perceptions and suggestions for supportive strategies. BMC Nurs. 2014;13(1). doi:10.1186/1472-6955-13-11

54. Kapusuz AG. Explaining stress and depression level of nurses: the effects of role conflict and role ambiguity. Int J Manag Sustain. 2019;8(2):61–66. doi:10.18488/journal.11.2019.82.61.66

55. Yu F, Raphael D, Mackay L, Smith M, King A. Personal and work-related factors associated with nurse resilience: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;93:129–140. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.014

56. Wen B, Zhou X, Hu Y, Zhang X. Role stress and turnover intention of front-line hotel employees: the roles of burnout and service climate. Front Psychol. 2020;11:11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00036

57. Hoboubi N, Choobineh A, Ghanavati FK, Keshavarzi S, Hosseini A. The impact of job stress and job satisfaction on workforce productivity in an Iranian petrochemical industry. Saf Health Work. 2017;8(1):67–71. doi:10.1016/j.shaw.2016.07.002

58. Orgambídez-Ramos A, Almeida H, Borrego Y. Social support and job satisfaction in nursing staff: understanding the link through role ambiguity. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(7):2937–2944. doi:10.1111/jonm.13675

59. Cable DM, DeRue DS. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(5):875–884. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.875

60. Rasool SF, Maqbool R, Samma M, Zhao Y, Anjum A. Positioning depression as a critical factor in creating a toxic workplace environment for diminishing worker productivity. Sustainability. 2019;11(9):2589. doi:10.3390/su11092589

61. Westland JC. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2010;9(6):476–487. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2010.07.003

62. Gardner DG, Cummings LL, Dunham RB, Pierce JL. Single-item versus multiple-item measurement scales: an empirical comparison. Educ Psychol Meas. 1998;58(6):898–915. doi:10.1177/0013164498058006003

63. Rhoades L, Eisenberger R, Armeli S. Affective commitment to the organization: the contribution of perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(5):825–836. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

64. Sjetne IS, Veenstra M, Ellefsen B, Stavem K. Service quality in hospital wards with different nursing organization: nurses’ ratings. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(2):325–336. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04873.x

65. Chang E, Hancock K. Role stress and role ambiguity in new nursing graduates in Australia. Nurs Health Sci. 2003;5(2):155–163. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00147.x

66. Hair JF, Astrachan CB, Moisescu OI, et al. Executing and interpreting applications of PLS-SEM: updates for family business researchers. J Fam Bus Strategy. 2021;12(3):100392. doi:10.1016/j.jfbs.2020.100392

67. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

68. Chin WW, Peterson RA, Brown SP. Structural equation modeling in Marketing: some practical reminders. J Mark Theory Pract. 2008;16(4):287–298. doi:10.2753/mtp1069-6679160402

69. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res. 1981;18(3):382–388. doi:10.1177/002224378101800313

70. Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci. 2014;43(1):115–135. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

71. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic press; 2013.

72. Gouldner AW. The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. Am Sociol Rev. 1960;25(2):161. doi:10.2307/2092623

73. Nguyen VQ, Taylor GD, Bergiel EB. Organizational antecedents of job embeddedness. Manag Res Rev. 2017;40(11):1216–1235. doi:10.1108/mrr-11-2016-0255

74. Fernandes S, Rinaldo AA. The mediating effect of service quality and organizational commitment on the effect of management process alignment on higher education performance in Makassar, Indonesia. J Organ Change Manag. 2018;31(2):410–425. doi:10.1108/jocm-11-2016-0247

75. Eliyana A, Ma’arif S, Muzakki M. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment effect in the transformational leadership towards employee performance. Eur Res Manag Bus Econ. 2019;25(3):144–150. doi:10.1016/j.iedeen.2019.05.001

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.