Back to Journals » HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care » Volume 12

Herbal Medicine Use and Determinant Factors Among HIV/AIDS Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy in Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Authors Shiferaw A, Baye AM , Amogne W, Feyissa M

Received 24 September 2020

Accepted for publication 3 December 2020

Published 15 December 2020 Volume 2020:12 Pages 941—949

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S283810

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Bassel Sawaya

Abebe Shiferaw,1 Assefa Mulu Baye,2 Wondwossen Amogne,3 Mamo Feyissa2

1Department of Pharmacy, Metu University, Metu, Oromia Region, Ethiopia; 2Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 3Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, College of Health Science, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Mamo Feyissa

Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Tel +251-913-423498

Email [email protected]

Background: The use of herbal medicine is common among HIV/AIDS patients due to chronic nature of the disease. However, the data are scarce on the extent of herbal medicine use and associated factors among HIV/AIDS patients while on antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Ethiopia.

Purpose: To assess the extent of herbal medicine use and associated factors among people living with HIV/AIDS on ART in Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Methods: A cross-sectional study design was conducted from February to June 2019. Patients were interviewed face to face using a structured questionnaire. Binary analysis using a chi-square test was used to determine the independent association of herbal medicine use to demographic and clinical characteristics, and multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression was done to identify predictability of herbal medicine use adjusted for other factors.

Results: A total of 318 participants were included in this study of which 26.1% of patients have used herbal medicines while on ART. The common herbal medicines used by participants were garlic (Allium stadium) 37.35% and Damakase (Ocimum lumiifolium) 22.9%. Most participants (60%) used herbal medicine for the treatment of opportunistic infections. The independent predictors for herbal medicine use were female gender (P=0.04; AOR 1.99, 95% CI 1.02– 3.88), age above 60 (P=0.046; AOR 2.79, 95% CI 1.02– 7.65), history of experiencing OIs (p=0.02; AOR 2.02, 95% CI 1.12– 3.65) and developing side effects from ART (p=0.001; AOR 2.80, 95% CI 1.55– 5.10).

Conclusion: A considerable proportion of HIV/AIDS patients used herbal medicine concomitantly with ART at TASH, Ethiopia. The determinant factors for use of herbal medicine were female gender, age above 60, experiencing OIs and developing side effects from ART.

Keywords: herbal medicine, HIV/AIDS, PLWH, Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a chronic infection causing enormous socio-economic challenges by affecting the young and economically productive population in Africa.1 Globally, there were approximately 37.9 million people living with HIV (PLWH) and 32.0 million people have died from AIDS-related illnesses since the start of the pandemic. The Eastern and Southern Africa region carries more than 50% (20.6 million) PLWH.2 Ethiopia is among the highly affected countries with 1.0% national HIV prevalence.2 Also, HIV/AIDS is among the top 10 killer diseases in Ethiopia.3

The introduction and early initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has resulted in a significant reduction of mortality and morbidity, and improvement in the quality of life of HIV/AIDS patients.4 However, the majority of HIV patients still use herbal medicines concomitantly with ART. The chronic nature of the disease and associated psychological and physical illnesses forces patients to try both conventional and traditional therapies to improve their quality of life and longevity.5 Herbal medicine is defined as herbs, herbal materials, herbal preparations, and finished herbal products, that contain active ingredient parts of plants, or plant materials, or combinations thereof6 is the most commonly used type of traditional medicine among PLWH.

Although the findings on the extent of herbal use by PLWH widely vary between studies, many studies reported a prevalence of herbal use that ranges from 50% to 95%.7–9 This rate is around three times higher than the rate of herbal utilization among uninfected people.10 The likely reason for differences in finding may be differences in study populations, and unstandardized definitions, and the inclusion/exclusion of specific types of therapies included in the study.

Herbal medicines are commonly used among PLWH for the management of ART side effects, treatment of opportunistic infections, other primary health care needs, and HIV itself.7,11–14 Besides, herbal medicines are used for general wellbeing, relaxation, pain, stress, spiritualism, and healing, improve energy level, as a dietary supplement.11,15,16

Among the factors associated with the increased use of herbal medicine among PLWH were shorter duration on ART (<4 years) and experienced ART side effects whereas, older age and optimally adherent patients were less likely to use herbal medicine.12 A similar study in South Africa reported, higher utilization of herbal medicine among HIV patients from a rural province, female, older, unmarried, employed, had limited education, or were HIV-positive for less than 5 years.17

Despite the increasing use of herbal medicines by PLWH,12,18 it is difficult to accurately estimate the prevalence of concomitant use of herbal medicine and conventional medicine, since patients using herbal medicine rarely inform their health care providers. Among patients who used herbal medicine 53% of the patients did not report herbal use to their treating physicians.5 Onifade et al also reported that 73.4% of the herbal medicine users denied use when asked by a medical practitioner.19 Similarly, Haile et al revealed that 61.2% of the HIV/AIDS patients who use herbal medicine did not disclose their use to their health care providers.8 Therefore, this may complicate the care and treatment of HIV as it may affect the outcome of ART.

Herbal medicines and faith healing is widely practiced for HIV/AIDS patients in Ethiopia.20 However, the extent and factors associated with herbal medicine use among HIV/AIDs patients on ART are not well documented although two studies were conducted in Gondar teaching hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Endale et al reported that 43.7% of the patients use herbal medicines while on ART.21 Another study in the same facility by Haile et al revealed that 70.8% of the HIV patients on ART have used herbal medicine. The most common herbal preparations used by people living with HIV/AIDS were Ginger (Zingiber officinale) (47%), Garlic (Allium sativum L.) (40.8%), and Moringa (Moringa stenopetala) (31.4%).8

With little evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of herbal use for HIV/AIDS management, the potential of herbal medicines to interfere with the effectiveness of ART is a pressing concern.22 Indeed, the use of certain types of herbs may compromise the efficacy of ART as a result of an unanticipated drug interaction or side effects from herbs.23 The potential for adverse outcomes may be amplified when HIV-positive patients do not disclose their herbal medicine use to their HIV care providers or when patients’ preferences for herbs interfere with the uptake of conventional HIV treatments. Hence, research determining the extent and the determinant factors for using herbal medicine is paramount important to recognize at the implication of herbal use in HIV/AIDS care, and anticipate patients with higher potential to use herbal medicine concomitantly with ART and provide counseling accordingly. Therefore, this study aims to assess the prevalence of herbal medicine use, reasons for use and associated factors among PLWH on ART attending of Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia.

Methodology

Study Area

This research was conducted in Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital (TASH), the largest referral and teaching hospital in Ethiopia, with around 700 beds and administered under Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences. The TASH is the main teaching hospital for both undergraduate and postgraduate health science students with specialized clinical services provided to the public. HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment services are given in the HIV clinic, which is one of the ambulatory care services delivered at TASH. The PLWH access ARV and related medicines from ART pharmacy of the hospital.

Study Design

A cross-sectional study design using structured questionnaires was conducted from February to June 2019.

Source and Study Population

The source population includes all PLWH attending HIV care and treatment at TASH whereas the study populations were all PLWH on ART who fulfill inclusion criteria and those who visited ART pharmacy for a refill of ARVs during the study period.

Inclusion Criteria

All HIV/AIDS patients who were greater than 18 years old and willing to participate were included in the study.

Study Variables

The dependent variable was concomitant use of herbal medicine with ART whereas independent variables included sociodemographic characteristics of participants such as age, gender, religion, marital status, educational status, and occupation; and clinical characteristics of participants such as duration since diagnosed, duration on ART, ART regimen, WHO staging, recent CD4 count and viral load, presence of opportunistic infection, presence of comorbidity, and occurrence of ART side effects.

Sample Size and Sampling

In this study, the sample size was calculated by using single population proportion formula with the following assumptions: 95% confidence interval, 5% margin of error, 70.8% prevalence of herbal use,8 which determine a final sample size of 318. A convenient sampling technique in which all participants who voluntarily give verbal consent were interviewed until the final sample size was reached.

Data Collection Methods

Data were collected by four graduating clinical pharmacy students after being trained by principal investigators on how to approach participants and appropriately fill the required data using the questionnaire. Data were collected by using a structured and pilot-tested questionnaire which was first prepared in English and then translated to the Amharic language (the official language of Ethiopia). The questionnaire contains questions on sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, monthly income, employment status, and educational level); Clinical characteristics (duration since diagnosis and ART, current use of ART, CD4 count, and symptoms experienced and any side effect encountered during treatment); and the practice of herbal medicine use (commonly used herbs, reasons for use, disclosure to treating physicians).

To maintain the quality data collected the questionnaire was pretested and ambiguous statements were rephrased to make clear. The completeness and accuracy of data were checked daily by principal investigators.

Data Analysis

The data was entered and analyzed using SPSS version 23. The descriptive statistics like frequency distribution and percentages were determined. Binary analysis using a chi-square test was used to determine the independent association of herbal medicine use to demographic and clinical characteristics. The variables with P<0.25 in the model were kept in multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression to identify predictability of herbal medicine use adjusted for other factors. The p-value of <0.05 is considered as significant.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Pharmacy, College of Health Science, Addis Ababa University. This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Also, permission was secured from the Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, ART clinic before the data collection. The research objective was explained to participants, and verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant as approved by the Ethical Review Committee. Furthermore, the confidentiality of participants was maintained by removing patient identifiers from the questionnaire and keeping the filled data secure.

Result

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

A total number of 318 HIV/AIDS patients on ART were included in this study. The majority of the participants were females, 197 (61.9%), married 141 (44.3%), within 30–45 age group 146 (45.9%), and have a mean age of 43.8 (±11.4) years. Regarding literacy among the participants 109 (34.3%) have completed secondary school, followed by 71 (22.3%) who completed primary school. The majority of the participant were followers of Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity 202 (63.5%) and Muslims 67 (21.1%).

Regarding the clinical characteristics; most of the study participant were on TDF/3TC/EFV 76 (55.3%) regimen, with recent CD4 count above 350 cells/dl 240 (75.5%) and undetectable viral load 267 (84.0%). Among the study participants, 127 (39.9%) patients were taking ART for 10–14 years. A total of 177 (55.7%) of the study participants had a history of opportunistic infection and 107 (33.65%) of patients encountered side effects from ART they are taking. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study participants are described in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participant, TASH, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (n=318) |

Herbal Medicine Use Among Patients

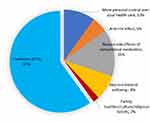

Among the study participants, a total of 83 (26.1%) used herbal medicine while on ART. The major reasons for using herbal medicine were to treat opportunistic infections 50 (60%) and reduce side effects from ART 48 (15.1%) (Figure 1). Majority (48 (56.47%)) of participants who used herbal medicine obtained information about herbs from their family members followed by friends/relatives 26 (32.9%). Among concomitant herbal medicine users, 7 (8.4%) visited traditional healers for management of HIV, and 5 (6.0%) believe that herbal medicine can cure HIV/AIDS.

|

Figure 1 The reason for use herbal medicine among PLWH in TASH, Ethiopia, 2019. |

Among herbal medicine users, only 7 (8.4%) disclosed use to their health care providers while most users 76 (91.6%) did not report it. The major reasons for not disclosing their herbal use to health care providers were the belief that they do not need the doctor’s approval 43 (51.8%), fear of not being understood/accepted by their health care provider 17 (20.5%) and they did not encounter their health care providers since herbal use 16 (19.3%).

Herbal Medicines Used

The most commonly consumed herbal medicines were Allium sativum 31 (37.35%) followed by Ocimum lamiifolium 19 (16.2%) and Linum usitatissimum 15 (12.75%). Herbal medicines were commonly consumed for the management of gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort, respiratory diseases and herpes zoster (Table 2).

|

Table 2 The Herbal Medicines Used Among PLWH in TASH, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (n=83) |

Factors Associated with Herbal Medicine Use

Based on the bivariate analysis of herbal medicine use with each sociodemographic and clinical variable using the Pearson’s chi-square test, age (p=0.001), gender (p=0.01), marital status (p=0.001), educational level (p=0.00), experiencing OIs (p=0.01) and encountering side effects from ART (p=0.00) have shown significant association. However, with multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression, the independent predictors of herbal medicine use were gender, age >60, experiencing OIs, and encountering side effects from the ART regimen. Female patients on ART use herbal medicine twice more than males (P=0.04; AOR 1.99, 95% CI 1.018–3.877). The odds of using herbal medicine among participants with age of 60 years and above is about 2.8 times higher than participants with age lower than 30 years (P=0.046; AOR 2.79, 95% CI 1.02–7.65). Patients with a history of OIs are twice more likely to use herbal medicine than those who did not encounter OIs (p=0.02; AOR 2.02, 95% CI 1.12–3.65). The participants who developed ART side effects were more likely to use herbal medicine than those who did not (p=0.001; AOR 2.80, 95% CI 1.55–5.10). Tables 3 and 4 show the association and determinant factors of herbal use with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study participants, respectively.

|

Table 3 The Association and Determinant Sociodemographic Factors for Herbal Medicine Use Among PLWH, TASH, Addis Ababa (N=318) |

|

Table 4 The Association and Determinant Clinical Factors for Herbal Medicine Use Among PLWH, TASH, Addis Ababa (n=318) |

Discussion

The extent of herbal medicine use among PLWH while on ART at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia is found to be 26.1%. This prevalence is relatively low as compared with similar studies conducted in Ethiopia and other African countries. A study conducted in the University of Gondar Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia reported 70.8% of herbal medicine use among PLWH while on ART.8 Similar studies reported higher prevalence of herbal medicine use among PLWH; 58% in Nigeria,24 and 63.5% and 46.4% in Uganda.7,25 The possible reason for the lower prevalence of herbal use in our study could be the fact that majority (91.5%) of participants of our study were urban residents of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia.

This study revealed that herbal medicines were used for the treatment of opportunistic infections (60%), to reduce ART side effects (15%), and improve wellbeing (8%). Similarly, a study by Lubinga et al found that 71.6% of the patients used herbal medicine to treat OIs in Uganda.25 Our study finding is also in line with a study by Littlewood and Vanable that reported major reasons for herbal medicine use were to alleviate HIV-symptoms and ART side-effects and to improve quality of life.26 However, dissatisfaction with conventional therapy (39.6%) and belief in advantages of herbal medicines (31%) were the major reasons for herbal medicine according to Haile et al.8 These differences could be the result of variation in beliefs towards ART and herbal medicines use among study participants.

The most commonly consumed herbal remedies by our study participants were Allium sativum and Ociumum lamiifolium in 37.4% and 22.6% of herbal medicine users, respectively. A study by Haile et al reported Zingier officinale (47%), Allium sativum (40.8%), and Moringa stenopetala (31.4%) as the most common herbal preparations used by PLWH.8 Another study also stated that the most frequently used herbal products, along with ART were Nigella sativa (22.92%), and Moringa oleifera (20.83%).21 The variations in the type of herbal medicines used could be related to differences in the culture of participants and the local availability of the herbs.

In the present study, significant determinants of herbal medicine use were being female gender, elderly age, experiencing OIs, and occurrence of side effects from ART. Similarly, herbal use is common among patients with HIV-related symptoms to alleviate such symptoms according to the study by Littlewood and Vanable.26 In contrast, only the educational level was a significant determinant of herbal medicine use as reported by Langlois-klassen et al7 and Haile et al.8 Besides, another study by Limsatchapanich et al reported that age, perceptions towards complementary and alternative medicine, and product accessibility were associated with the use of herbal medicine among PLWH.10

The majority of herbal medicine users rarely disclose their use of herbal medicines to their health care providers despite the importance of disclosure for effective management, counseling, and monitoring treatment outcomes. Our study revealed that only 8.4% of the herbal medicine users informed their health care providers about their herbal use. This finding is consistent with the findings of 7.7% reporting of herbal medicine used to health care practitioners in Uganda25 but lower than finding of 38.8% reporting herbal use to health care providers in Gondar, Ethiopia.8 The patient’s belief about herbal medicines as they are safe and lack of understanding about the benefit of informing health care providers might influence their communication about herbal use.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Despite the improved accessibility and early initiation of ART, a substantial proportion of patients use herbal medicine concomitantly with ART at TASH, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The major reasons for patients to use herbal medicines were treatment of OIs and ART side effects, and improve general wellbeing. The most commonly consumed herbal remedies were Allium sativum and Ocimum lumiifolium. Gender, elderly age, history of OIs, and occurrence of ART side effects are determinant factors that are significantly associated with herbal medicine use among PLWH on ART at TASH. Large-scale, multicenter studies are required to explore the extent and determinants for herbal use among PLWH to develop interventions that ensure optimal care for patients at the national level.

The Strengths and Limitation of the Study

This study was conducted in the largest teaching and referral hospital in Ethiopia. The sample size is large and representative of the total PLWH on ART in TASH. However, as it is a single-site study, the finding cannot represent the whole PLWH on ART in Addis Ababa. This study is based on a cross-sectional study design; hence, causal inference between independent factors and herbal medicine use cannot be made.

Abbreviations

ART, anti-retroviral therapy; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OI, opportunistic infections; PLWH, people living with human immunodeficiency virus; WHO, World Health Organization; TASH, Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital; UNAIDS, United Nation Agency for International Development.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of the study will be available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all study participants and Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital for allowing us to conduct our study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by Addis Ababa University.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Dixon S, Mcdonald S, Roberts J. The impact of HIV and AIDS on Africa’s economic development. BMJ. 2002;324:232–234. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7331.232

2. UNAIDS. UNAIDS DATA 2019. 2019.

3. FMOH. Health and Health Related Indicators 2008 EFY (2015/2016); 2016.

4. WHO. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach.

5. Orisatoki RO, Oguntibeju OO. The role of herbal medicine use in HIV/AIDS treatment. Arch Clin Microbiol. 2010;1(3):1–4.

6. Robinson MM, Zhang X. Traditional Medicines: Global Situation, Issues and Challenges. The World Medicines Situation. Swizerland, Genena: WHO; 2011.

7. Langlois-klassen D, Kipp W, Jhangri GS, Rubaale T. Use of traditional herbal medicine by AIDS patients in Kabarole District, Western Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77(4):757–763. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.757

8. Haile KT, Ayele AA, Mekuria AB, Demeke CA, Gebresillassie BM, Erku DA. Traditional herbal medicine use among people living with HIV/AIDS in Gondar, Ethiopia: do their health care providers know? Complement Ther Med. 2017;35:14–19. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2017.08.019

9. Kelso-chichetto NE, Okafor CN, Harman JS, Cook CL, Cook RL, Cook RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use for HIV management in the State of Florida: medical monitoring project. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22(11):880–886. doi:10.1089/acm.2016.0190

10. Limsatchapanich S, Sillabutra J, Nicharojana LO, Section CP, Provincial S, Health P. Factors related to the use of complementary and alternative medicine among people living with HIV/AIDS in Bangkok, Thailand. Health Sci J. 2013;7:436–446.

11. CATIE. A Practical Guide to Herbal Therapies for People Living with HIV; 2005.

12. Namuddu B, Kalyango JN, Karamagi C, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with traditional herbal medicine use among patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy in uganda. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:855–863. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-855

13. Gyasi RM, Tagoe-Darko E, Mensah CM. Use of traditional medicine by HIV/AIDS patients in Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana: a cross-sectional survey. Am Int J Contemp Res. 2013;3(4):117–129.

14. Cichello S, Tegegne SM, Yun H. Herbal medicine in the management and treatment of HIV-AIDS - a review of clinical trials. Aust J Herb Med. 2014;26(3):100–114.

15. Orisatoki RO, Oguntibeju OO. The role of herbal medicine use in HIV_AIDS treatment. Insight Med Publ. 2010;1(3):1–4.

16. Maroyi A. Alternative medicines for HIV/AIDS in resource-poor settings: insight from traditional medicines use in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop J Pharm Res. 2014;13(9):1527–1536. doi:10.4314/tjpr.v13i9.21

17. Hughes GD, Puoane TR, Clark BL, Wondwossen TL, Johnson Q, Folk W. Prevalence and predictors of traditional medicine utilization among persons living with aids (PLWA) on antiretroviral (ARV) and prophylaxis treatment in both rural and urban areas in South Africa. Afri J Tradit Complement Alternat Med. 2012;9(4):470–484.

18. Liu JP, Manheimer E, Yang M. Herbal medicines for treating HIV infection and AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2005(3).

19. Onifade AA, Ajeigbe KO, Omotosho IO, Rahamon SK, Oladeinde BH. Attitude of HIV patients to herbal remedy for HIV infection in Nigeria. Niger J Physiol Sci. 2013;28:109–112.

20. Kloos H, Mariam DH, Kaba M, Tadele G. Traditional medicine and HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia: herbal medicine and faith healing: a review. Ethiop J Heal Dev. 2013;27(2):141–155.

21. Endale A, Sebsibe FTW, Tadesse WT. Pattern of traditional medicine utilization among HIV/AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy at a University Hospital in Northwestern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:1–6. doi:10.1155/2017/1724581

22. Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol. 2014;4:1–10. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00177

23. Staines SS. Herbal medicines: adverse effects and drug-herb interactions. J Malta Coll Pharm Pract. 2011;(17):38–42.

24. Idung AU, Abasiubong F. Complementary and alternative medicine use among HIV-infected patient’s on anti-retroviral therapy in the Niger Delta Region, Nigeria. Clin Med Res. 2014;3(5):153–158. doi:10.11648/j.cmr.20140305.19

25. Lubinga SJ, Kintu A, Atuhaire J, Asiimwe S. Concomitant herbal medicine and antiretroviral therapy (ART) use among HIV patients in Western Uganda: a cross-sectional analysis of magnitude and patterns of use, associated factors an. AIDS Care. 2012;24(11):37–41. doi:10.1080/09540121.2011.648600

26. Littlewood RA, Vanable PA. Complementary and alternative medicine use among HIV+ people: research synthesis and implications for HIV Care. AIDS Care. 2008;20(8):1002–1018. doi:10.1080/09540120701767216

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.