Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 15

Gender-Based Violence – Magnitude and Types in Northwest Ethiopia

Authors Gebresilassie KY , Melesse AW , Birhan TY, Taddese AA

Received 28 February 2023

Accepted for publication 11 July 2023

Published 18 July 2023 Volume 2023:15 Pages 1083—1091

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S409172

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

Keflie Yohannes Gebresilassie,1 Alemakef Wagnew Melesse,2 Tilahun Yemanu Birhan,2 Asefa Adimasu Taddese3

1Midwifery Directorate, College of Medicine and Health Science, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia; 2Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Medicine and Health Science, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia; 3Department of Health Informatics /Biostatistics/, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Keflie Yohannes Gebresilassie, Email [email protected]

Background: Violence Against Women (VAW) becomes a serious public health issue as unnecessary morbidity and mortalities affect women and girls. Women who experience violence had the possibility of another of violence. Although gender-based violence (GBV) is a common problem in Ethiopia, the burden is not well studied.

Objective: This study determines the magnitude of Gender-Based Violence among women receiving Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in a Specialized Hospital.

Methods: Institution-based retrospective follow-up study was conducted at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital among gender-based violence (GBV) service users from January 2017 to January 2022. Data were collected from register logbooks and also medical records for some variables, using a tool prepared by refereeing literature and adapting locally available resources and researchers experiences. Epi-info 7 was used to enter the data and exported it to SPSS V-23 for analysis. Descriptive statistics like frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations are computed for all variables.

Results: The lifetime proportion of sexual and physical violence was found to be 81% and 5%, respectively, while 3% of women experienced both sexual and physical violence. One hundred seventy (29.4%) of the incidents were done by an intimate-partners (boyfriend/husband). The majority (86%) had extra genital injuries. After genital examination, about one-fourth (25%) of survivors had fresh hymenal tears. About three-fourths (75.1%) of the survivors visit the health facility within threes day after the incident.

Conclusion: The study found that GBV is common in Northwest Ethiopia. Future research should involve sensitive methods and grounded approaches to explore survivors’ experiences and views on local gender cultures and other contextual factors. Establishing One-stop-center could improve the quality of the services provided to the women.

Keywords: Gender, Sexual, Physical, Violence, Women, Health, Ethiopia

Introduction

Gender-Based Violence (GBV) refers to a broad category of unconsented actions (physical, sexual, or mental injury, threats, coercion, and abuse) motivated by distinctions between genders as male and female.1 Most communities accept violent acts and perpetrators did not feel accountable for their crimes and kept violating other women. These practices also prevent women to use available services that she needs.2

The lifetime prevalence of GBV varies, from 11% to 47% in high-income countries and 16–47% in Africa. More than one-third (37%) of Ethiopian women experience the problem.3 Other studies also estimated that nearly 1 in 3 women experience physical/sexual intimate violence or non-partner sexual assault in their lifetime.4 Violence against Women (VAW) becomes a serious public health issue5 as it seriously affects survivors in the short- and long-term periods.6 WHO multi-country study found that VAW is more common in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC)7 and they face difficulties to provide the necessary care for survivors.8

GBV has psychological (post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and suicide);9 reproductive health-related (sexually transmitted infections, unplanned pregnancies, poor maternal health outcomes); and physical consequences.10 Women who experience violence have the possibility of experiencing it again and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) survivors were more vulnerable. Individuals, families, communities, and the bigger socioeconomic and political circumstances contribute to VAW.11 Risky sexual behaviors, homelessness, and having an orphaned teenager were characteristics associated with an individual or family.12 Housemaids encounter various neglected health ailments from their employers other than the common forms of violence.13 Survivors had mental health problems like depression (44.9%) and anxiety (41.9%)14 as a result of sexual and physical abuse.14 Disruption of family relationships,15 peer pressure,16 family history of violence, and limited access to basic needs exacerbate GBV. In many societies, domestic violence has been accepted. Women were compelled to marry their abusers; forced to leave their home country, and endure other physical and sexual abuses along the way.17 VAW could also result from conflict and have an impact on the survivors’ overall health.18

GBV is now a common occurrence in Ethiopia, where the Amhara Region is home to many survivors and internally dsplaced populatons due to humanitarian crises. Women are exposed to violence and life-threatening situations daily due to human-made (political instability and ethnic- and religion-based conflict and war) and natural disasters, such as drought and flooding. The war impacted more than 10.6 million people and women children and the elderly were vulnerable health both directly (sexual violence massacre of civilians and displacement) and indirectly (lack of legal protection interruption of access to health care mental and psychological problems) are among the few. Unpublished regional reports showed that thirteen of the twenty-one zones were affected. Health facilities (50 hospitals 453 health centers and 150 health posts) were extensively damaged More than 720224 internally displaced persons are living in the region. Despite these circumstances, the burden, types, and effects of GBV are not well understood in the area. Our study sought to fill this knowledge vacuum and suggest strategies for the local GBV response and prevention actors and ensure the provision of quality survivors-centered care.

Methodology

Study Design and Setting,

Gondar Zone is bordered by neighboring countries and there is conflict due to ethnic, religious, land dominance, and border issues. The University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital is located 735 km from the Northwest of the capital city, Addis Ababa. The hospital was established in 1954 to address locally available communicable diseases during the time. It serves for more than 13 million people and provides specialized and referral health services in all health disciplines including reproductive health, such as Gender-Based Violence in the catchment area. Currently, there are more than 960 beds and 30 wards/service delivery areas. In the hospital GBV services provided at Michu Clinic (Sexual and Reproductive Health service unit established in January 2017) under midwifery coordination offices. The service is provided by trained gynecologists and midwives. An institution-based retrospective study was conducted among women who visited the Hospital for GBV services.

Study Population and Sampling

All women who received GBV services during the study period were included, whereas those who had incomplete registration and lost medical records were excluded from our study.

Data Collection and Quality Control

A five-year of data (from January 2017 to January 2022- these periods were selected as the hospital started the services in an organized manner having separate dedicated rooms, register books and service providers) were collected from written GBV register logbooks and medical record books for some variables. The data was collected using a tool prepared by refereeing literature and adapting locally available resources and researchers’ experiences. A two-day training was given to two data collectors and one supervisor on the objective of the study, the confidentiality of participant records, and other issues. The collected data were assessed for accuracy and incomplete data were filled in by referring medical records of the participants. The tool was prepared in English and has socio-demographic variables, sexual characteristics, and questions on the type, consequences, and management of GBV services provided to the participants.

Data Management and Analysis

Data were entered into Epi-info 7 and exported to SPSS 23 for analysis. Descriptive statistics like frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations are computed for all variables. The data was presented using tables and graphs.

Result

Socio-Economic and Obstetric Characteristics

In our study, out of 612 eligible women on the logbooks, 578 had complete and accurate data and the remaining were excluded due to incomplete data. More than two-fifths (43.8%) were between the ages 15–19 years, while sixty-one (10.6%) were below nine years old. About three-fifths (60.4%) were urban dwellers. Regarding their relationship, 529 (91.3%) were single, and nineteen (3.2%) were married. The majority of the survivors were students (89.8%), while fourteen (2.1%) were daily-laborer. Three hundred ninety-four (66.2%) had a regular menstrual pattern and were nulliparous (98.2%) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Economic and Obstetric Characteristics of Study Participants in Northwest Ethiopia, 2022 |

Sexual Characteristics of the Respondents

About three-fifths (60.4%) were sexually active and forty-seven (8.1%) had experienced prior GBV. More than one-third (35.6%) of the incidents were performed in hotels/pensions and were performed by an intimate-partners (boyfriend/husband) (29.4%). More than one-third of the perpetrators (37.4%) were strangers and use (29.1%) alcohol, drugs, and knives at the time of the incident to threaten and/or weaken the survivors. Regarding sexual intercourse, almost all (98.8%) were through the vaginal route, and about three fourth (75.1%) of the survivors visited the health facility within threes day after the incident (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Sexual Characteristics Study Participants in Northwest Ethiopia, 2022 |

Magnitude of GBV

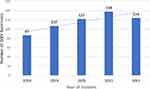

Nearly three-fourth (122) of the incidents occurred in the year 2020 (Figure 1). The lifetime proportion of sexual and physical violence was 81% and 5%, respectively, while 3% of women experienced both forms. The majority (86%) had extra-genital injuries and experienced painful examinations (68%). After genital examination, about one-fourth (25%) had fresh hymenal tears, and overall positive laboratory results (including HIV/AIDS, sperm analysis, and pregnancy tests) were found in 4% of the survivors (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Consequences of GBV on Survivors in Northwest Ethiopia, 2022 |

|

Figure 1 Number of GBV survivors disaggregated by year of Incident in Northwest Ethiopia 2023. |

Management/Treatments Provided for GBV Survivors

GBV management includes interventions for immediate emergencies and wound care; provision of prophylaxis for prevention of pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and wound infections (if occurred); and vaccination for Hepatitis B and other locally available vaccines. In our study, 54 (9.3%) of the survivors received wound care and broad-spectrum antibiotics. More than half (52.8%) received contraceptives, majorly (62%) emergency pills, for the prevention of pregnancy.

Regarding Sexually Transmitted Infections, three hundred seventy (64%) received prophylaxis. Three hundred forty-seven (60%) were eligible for post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV/AIDS and provided with 1E Regimen- TDF-3TC-EFV, while eight (1.4%) received the Hepatitis B virus vaccine after checking their negative status.

All the survivors got psychological counseling from a clinical psychologist and about one-fourth (25.6%) were linked to legal and economic support (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Management and/or Treatments Provided for GBV Survivors in Northwest Ethiopia, 2022 |

Discussion

Nowadays GBV becomes common to everyone and everywhere irrespective of their differences in terms of multiple aspects. The magnitude of the problem is the a hidden iceberg and conducting studies assessing the magnitude of the different forms could have an input on all the efforts of prevention and responses. The Ethiopian government also prepared a Standard Operating Procedure for the response and prevention of sexual violence in Ethiopia and our study investigated the burden of the problem and comprehensive responses to the psychological, medical, social, and legal needs of GBV survivors after the launching of this guideline19 and purposed to deliver evidence for policy input.

The percentage of sexual violence and physical violence was 81% and 5%, respectively. Our finding was higher than other studies conducted in different areas of Ethiopia20 and other countries.21 This implies how prevalent the problem is and still women are at risk of sexual and physical assault, as well as having limited political and social sway. Additionally, in the region most of the community accepts male dominance over females as a cultural norm/practice, creating an unfavorable environment and devaluing women’s preferences, and exposed to different reproductive health problems.22 Furthermore, early marriage, the low educational status of women and men, and a lack of community awareness regarding earlier prevention of violence might contribute to the observed findings in our study area.23 In this study, the majority (86%) of survivors of violence reported extra genital injuries, and 68% of survivors had painful examinations. After genital inspection, one-fourth (25%) of the survivors had recent/fresh hymenal tears. The occurrence of such additional injuries may have further effects, and an individual’s sense of self and self-esteem can be seriously damaged, which may have a further psychological impact. According to reports, young people who experience psychological abuse “feel worthless, broken, rejected, undesired, or in danger”.24,25 Conflict, post-conflict, and displacement scenarios now in Ethiopia could increase current violence and introduce new types of VAW.

WHO recommends the provision of care and support as early as possible, including prophylaxis within 72 hours for prevention of pregnancy and HIV/AIDS and the provision of locally available vaccines for Hepatitis B Virus and Tetanus Toxoid.26 In our study, about one-fourth (24.9%) of the survivors were not able to visit the health facility within threes day after the incident and miss the aforementioned prophylaxis. This will have an impact on the women’s reproductive health life’s and necessitate to have a strong referral and linkage between the different healthcare levels and community networks. Moreover, only eight (1.4%) received vaccines for Tetanus Toxoid and Hepatitis B Virus. This indicates the existence of disorganized and disintegrated service delivery and a gap in vaccination coverage for GBV survivors and has to be accessible and affordable to break the afterward sequel and violates the guiding principles.19

More than one-third (35.6%) of the incidents were performed in hotels/pensions by an intimate-partners (boyfriend/husband) (29.4%). This indicates the need to identify stakeholders for GBV response and prevent locally available means of committing violence against women, which include police, social welfare, women and children affairs, justice, community representatives, professional associations, and GBV actors. These stakes need to intervene on supportive laws and regulations, places, times/seasons, and other circumstances, which have contributed factors to the occurrence of violence.

In this study, the majority (62%) of the survivors received emergency medications, and prophylaxis to prevent pregnancy (52.8%). Clinical psychologists provided psychological therapy and support to all survivors, and about one-fourth (25.6%) were connected with other psychosocial supports like legal and financial aid. However, a lack of resources frequently led to people being placed on lengthy waiting times, making prompt early intervention particularly challenging. As a result, women received care when they were in immediate danger and life-threatening conditions. The short-term nature of funding was also detrimental to establishing and preserving relationships with survivors and hindered organizations’ ability to expand and continue to create successful programs. This was evident in that vaccination coverage for Hepatitis B Virus and Tetanus Toxoid was very low (1.4%) due to frequent interruptions of supplies.

Conclusion and Recommendations

GBV is prevalent in North West Ethiopia, and it is a public health and human rights problem. We suggest that research may be most fruitful where it involves sensitive methods and grounded approaches that listen to survivors’ accounts of their experiences and views on local gender cultures and other relevant contextual factors. In addition, effective community networks served as both enablers and barriers to support survivors, demonstrating the importance of strong linkages between health facilities and communities. Establishing fully equipped and supplemented One-Stop-Centers (OSC) for GBV survivors in the hospital could help to provide survivor-centered care and solve unnecessary delays in receiving timely care - to meet the recommended standards - and facilitate the legal process as they are integrated and provided under one roof. Regional Health Bureaus also better to work with the community and other stakeholders working in the area to tackle GBV facilitators in the society at regional level.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The study shares the limitations of cross-sectional study design and secondary data collection and under-reporting of data might exist. The study also did not explore survivors’ experiences in the facility. Manual register logbooks also lack data on other forms of GBV. The unavailability of an Electronic version of data registration was a challenge during the data collection process and the reasons were not assessed by the authors. The study also did not assess the legal aspects of the services.

Abbreviations

GBV,Gender-Based Violence; IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; STI, Sexually Transmitted Infection; VAW, violence against women; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

Our study fully complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Support letter was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Public Health (IPH), College of Medicine and Health Sciences, the University of Gondar, Letter of Permission was obtained from the Chief Clinical Director (CCD) of the Comprehensive Specialized Hospital and submitted to Midwifery coordination office. During GBV service provision, all the survivors consented to their willingness to the service procedures and use of the data to generate evidence for program improvements and policy input. We collected our data from GBV register logbooks (not from the clients/survivors) and hospital patent cards, after getting informed oral consent from respective hospital ward and card room heads. The confidentiality of study participants was maintained by removing personal identifiers on the data collection tool and limiting very sensitive data. Moreover, at all stages, methods were carried out by relevant guidelines and regulations.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our gratitude to the Amhara Regional Health Bureau and the University of Gondar for supporting this investigation and the data collection process. We appreciate the support of the hospital personnel, data collectors, and supervisors.

Author Contributions

All the authors had significant contributions to conception, study design, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

There is no funding received for conducting this study.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

1. Raftery P. Gender-Based Violence (GBV) coordination in humanitarian and public health emergencies: a scoping review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2022;16(1):37.

2. Committee I-AS. Guidelines for Integrating Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action: Reducing Risk, Promoting Resilience and Aiding Recovery. Inter-Agency Standing Committee; 2015.

3. Fulu E, Miedema S, Roselli T, et al. Pathways between childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, and harsh parenting: findings from The UN multi-country study on men and violence in Asia and the pacific. Glob Public Health. 2017;5(5):E512–E22.

4. Kaufman MR, Grilo G, Williams AM, et al. The intersection of gender-based violence and risky sexual behaviour among university students in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. Psychol Sex. 2020;11(3):198–211. doi:10.1080/19419899.2019.1667418

5. Global database on the prevalence of violence against women; 2021. Available From: Https://Srhr.Org/Vaw-Data/Data?Region=South-Eastern+Asia&Region_Class=SDG&Violence_Type=Ipv&Violence_Time=Lifetime&Age_Group=15_49.

6. Sikder SS, Ghoshal R, Bhate-Deosthali P, Jaishwal C, Roy N. Mapping the health systems response to violence against women: key learnings from five LMIC settings (2015–2020). BMC Women’s Health. 2021;21(1):360. doi:10.1186/s12905-021-01499-8

7. García-Moreno C, Pallitto C, Devries K, Stöckl H, Watts C, Abrahams N. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. World Health Organization; 2013.

8. Kwagala B, Galande J. Disability status, partner behavior, and the risk of sexual intimate partner violence in Uganda: an analysis of the demographic and health survey data. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1872. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-14273-8

9. Murray SM, Yount KM, Krause KH, Miedema SS. Preventing gender-based violence victimization in adolescent girls in lower-income countries: systematic review of reviews. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2017;192:1–13.

10. Nöthling J, Simmons C, Suliman S, Seedat S. Trauma type as a conditional risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder in a referred clinic sample of adolescents. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;76:138–146. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.05.001

11. Nunbogu AM, Elliott SJ. towards an integrated theoretical framework for understanding water insecurity and gender-based violence in low-and middle-income countries (LMICS). Health Place. 2021;71:102651. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102651

12. Pachankis JE, Bränström R, Grose RG, et al. Sexual and reproductive health outcomes of violence against women and girls in lower-income countries: a review of reviews. J Interpers Violence. 2021;58(1):1–20.

13. Sommer M, Muñoz-Laboy M, Williams A, et al. How gender norms are reinforced through violence against adolescent girls in two conflict-affected populations. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;79:154–163. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.02.002

14. Spangaro J. The impact of interventions to reduce risk and incidence of intimate partner violence and sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict states and other humanitarian crises in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 2021;15(1):86.

15. Tadesse AW. Prevalence and associated factors of intimate partner violence among married women during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions: a community-based study. Depress Res Treat. 2022;37(11–12):Np8632–Np50.

16. Sharma V, Leight J, Verani F, Tewolde S, Deyessa N. Effectiveness of A culturally appropriate intervention to prevent intimate partner violence and HIV transmission among men, women, and couples in rural Ethiopia: findings from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2020;17(8):E1003274. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003274

17. Tantu T, Wolka S, Gunta M, Teshome M, Mohammed H, Duko B. Prevalence and determinants of gender-based violence among high school female students in wolaita sodo, Ethiopia: an institutionally based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):540. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08593-w

18. Torres-Rueda S, Ferrari G, Orangi S, et al. What will it cost to prevent violence against women and girls in low- and middle-income countries? Evidence from Ghana, Kenya, Pakistan, Rwanda, South Africa, and Zambia. Health Policy and Planning. 2020;35(7):855–866. doi:10.1093/heapol/czaa024

19. Wirtz AL, Glass N, Pham K, et al. Development of A screening tool to identify female survivors of gender-based violence in a humanitarian setting: qualitative evidence from research among refugees in Ethiopia. Confl Health. 2013;7(1):13. doi:10.1186/1752-1505-7-13

20. Wondimu H. Gender-based violence and its socio-cultural implications in south west Ethiopia secondary schools. Heliyon. 2022;8(7):E10006. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10006

21. Muluneh MD, Stulz V, Francis L, Agho K. Gender based violence against women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):903. doi:10.3390/ijerph17030903

22. Reeves A, Steele S, Stuckler D, Mckee M, Amato-Gauci A, Semenza JC. Gender violence, poverty and HIV infection risk among persons engaged in the sex industry: cross-national analysis of the political economy of sex markets in 30 European and central Asian Countries. HIV Med. 2017;18(10):748–755. doi:10.1111/hiv.12520

23. Scheer JR. Gender-based structural stigma and intimate partner violence across 28 countries: a population-based study of women across sexual orientation, immigration status, and socioeconomic status. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2022;37(11–12):Np8941–Np64.

24. St John L, Walmsley R. The latest treatment interventions improving mental health outcomes for women, following gender-based violence in low-and-middle-income countries: a mini review. Front Glob Women’s Health. 2021;2:792399. doi:10.3389/fgwh.2021.792399

25. Stark L, Asghar K, Seff I, et al. How gender- and violence-related norms affect self-esteem among adolescent refugee girls living in Ethiopia. Global Mental Health. 2018;5:E2.

26. Hirpa Y. Sexual Abuse Among Female Street Children: the Case of Lideta Sub City, Addis Ababa [Unpublished Master’s Thesis]. Addis Ababa University; 2007.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.