Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 11

Factors associated with the risk of relapse in schizophrenic patients after a response to electroconvulsive therapy: a retrospective study

Authors Shibasaki C, Takebayashi M, Fujita Y, Yamawaki S

Received 14 September 2014

Accepted for publication 22 October 2014

Published 5 January 2015 Volume 2015:11 Pages 67—73

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S74303

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Chiyo Shibasaki,1 Minoru Takebayashi,1,2 Yasutaka Fujita,1 Shigeto Yamawaki3

1Division of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, Institute for Clinical Research, National Hospital Organization (NHO) Kure Medical Center and Chugoku Cancer Center, Kure, Hiroshima, Japan; 2Department of Psychiatry, NHO Kure Medical Center and Chugoku Cancer Center, Kure, Hiroshima, Japan; 3Department of Psychiatry and Neurosciences, Division of Frontier Medical Science, Programs for Biomedical Research, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Hiroshima University, Minami-ku, Hiroshima, Japan

Purpose: Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective treatment for depression and schizophrenia. However, there is a high rate of relapse after an initial response to ECT, even with antidepressant or antipsychotic maintenance therapy. This study was carried out to examine the factors that influence the risk of relapse in schizophrenic patients after a response to ECT.

Patients and methods: We retrospectively reviewed the records of 43 patients with schizophrenia who received and responded to an acute ECT course. We analyzed the associated clinical variables and relapse after response to the acute ECT. Relapse was defined as a Clinical Global Impressions Improvement score ≥6 or a psychiatric rehospitalization.

Results: All patients were treated with neuroleptic medication after the acute ECT course. The relapse-free rate of all 43 patients at 1 year was 57.3%, and the median relapse-free period was 21.5 months. Multivariate analysis showed that the number of ECT sessions was associated with a significant increase in the risk of relapse (hazard ratio: 1.159; P=0.033). Patients who were treated with adjunctive mood stabilizers as maintenance pharmacotherapy after the response to the acute ECT course were at a lower risk of relapse than were those treated without mood stabilizers (hazard ratio: 0.257; P=0.047).

Conclusion: Our study on the recurrence of schizophrenia after a response to an acute ECT course suggests that the number of ECT sessions might be related to the risk of relapse and that adjunctive mood stabilizers might be effective in preventing relapse.

Keywords: electroconvulsive therapy, relapse, risk factors, schizophrenia

Introduction

Since the first successful electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) treatment course in 1938, ECT been used for a variety of psychiatric disorders, and its use for the treatment of schizophrenia spread from the 1940s through the 1950s. When antipsychotic medication was introduced in the 1950s, the use of ECT for schizophrenia declined.1 However, due to resistance and intolerance to pharmacotherapy in some patients, ECT can be beneficial2 and therefore ECT for schizophrenia is still being performed worldwide.3,4 Several national guidelines suggest the use of ECT for schizophrenia in particular circumstances.5 The American Psychiatric Association (APA)6 suggests that “ECT is effective for psychotic exacerbations in schizophrenic patients, when illness is of the catatonic type, when the psychotic symptoms are abrupt or recent in onset, or when there is a past history of favorable response to ECT” and “ECT is effective for psychotic disorders related to schizophrenia, that is, schizophreniform disorders and schizoaffective disorders”.

Although ECT is an effective acute treatment for patients with severe symptoms, one important problem is the high relapse rate. Even with antipsychotic therapy, relapse rates were >60% at 1 year after ECT in schizophrenic patients.7,8 There are only a few studies reporting the factors that predict a relapse after an initial response to ECT in schizophrenia. A high neuroleptic dose before acute ECT8 and the observation of self-harming behaviors at baseline7 seem to enhance the risk of relapse. Therefore, additional information on the factors associated with relapse is needed in order to determine the optimal prophylaxis for such cases during the stable phase. We investigated the factors that influence the risk of relapse in schizophrenic patients after demonstrating a response to ECT.

Patients and methods

Patients

The inclusion criteria for the study were patients who 1) were diagnosed with schizophrenia based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 guideline by at least two trained psychiatrists, 2) received an acute ECT course between October 2005 and September 2011, regardless of having received an acute course of ECT prior to October 2005, at the National Hospital Organization (NHO) Kure Medical Center, and 3) responded to the acute ECT course.

The exclusion criteria were patients who 1) were diagnosed with schizoaffective disorders or persistent delusional disorders, 2) did not respond to the acute ECT course, and 3) received continuous or maintenance (c/m) ECT, as the purpose of this study was to identify risk factors of relapse after acute ECT, not after c/m ECT.

In the current study, we evaluated the responsiveness to acute ECT using the Clinical Global Impressions Improvement (CGI-I) Scale score, as follows: 0= Not assessed; 1= Very much improved; 2= Much improved; 3= Minimally improved; 4= No change; 5= Minimally worse; 6= Much worse; and 7= Very much worse. Responders to the acute ECT course were defined as patients with a CGI-I Scale score ≤3 after acute ECT, and nonresponders were defined as those with a CGI-I score ≥4. If two or more acute ECT courses were received by the same patient during the study period (2005–2011), the observation period was defined as the time since completing the first acute ECT course.

Data source

The data used for the study were obtained from medical records. The data collected included demographic variables, clinical variables, and maintenance psychotropic-related variables. The demographic and clinical variables included the age, sex, subtype of schizophrenia, age of onset of illness, number of psychotic episodes (including current episode), number of ECT sessions, score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) before and after ECT, and chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalence before ECT. In this study, the evaluation of the symptom was carried out by a trained psychiatrist, different from those who diagnosed schizophrenia. The maintenance psychotropic-related variables included the classification of antipsychotics, CPZ equivalence, and use of additional medication (mood stabilizers [lithium carbonate, sodium valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine], antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and anticholinergics). The daily doses were calculated by converting the antidepressant, benzodiazepine, and anticholinergic doses to imipramine, diazepam, and biperiden equivalents, respectively. The kind of antipsychotic or the daily doses in some patients were changed because of worsening of their condition, but we calculated the kind and CPZ equivalence at the time of discharge, not at the time of relapse, because there were many cases that met the criteria of relapse just after the change of medication.

When two or more antipsychotic drugs were used for a single patient, the main antipsychotic drug was defined as the one with the highest CPZ-equivalent dose. The classification of antipsychotics into the first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) or second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) category was conducted according to the literature.9

We adhered to ethical considerations when gathering data so that individuals could not be identified. The ethics committees of our centers approved this retrospective study.

ECT treatment procedures

Only modified ECT with the cooperation of an anesthesiologist was used. Without premedication, patients received intravenous thiamylal sodium (2–3 mg/kg) and suxamethonium chloride (0.5–1.0 mg/kg) for anesthesia. The ECT device used was the Thymatron System IV® brief-pulse square-wave apparatus (Somatics Inc., Lake Bluff, IL, USA). Electrodes were positioned in the bilateral fronto-temporal region. Only one adequate seizure was required for each session, which was defined as an electroencephalographic seizure lasting >25 seconds with a high-amplitude, slow-wave and postictal suppression. The initial stimulus dose was determined using the half-age method.10 If an adequate electroencephalographic seizure occurred in one session, the stimulus energy of the next session remained the same. When a missed or an inadequate seizure occurred, the patient was restimulated with 1.5–2 times the stimulus energy. The maximum number of stimulations for each treatment session was two. ECT was administered at a maximum of three times per week. If any adverse effects (eg, cognitive dysfunction, delirium) occurred, the frequency of the ECT schedule was reduced to once or twice per week, or the ECT was stopped. On the basis of the APA guidelines, ECT was continued until the patient was asymptomatic or when the psychiatrist judged that the patient had benefited as much as possible.6 All patients were treated with antipsychotics during the ECT course. After the purpose and procedure of ECT was fully explained, written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their family members prior to acute ECT.

Treatment during the follow-up period after the acute ECT course

All patients were treated with neuroleptic medication to prevent relapse after the acute ECT course. The attending psychiatrist selected the type and dosage of antipsychotics and additional medication on a case-by-case basis. For antipsychotics, SGAs were mainly used, while an FGA was selected when the effects of SGAs were insufficient.

Outcomes

In the current study, the time to relapse was defined as the time between ECT and the date of an evaluation at which patients had a CGI-I score ≥6 or if they required psychiatric rehospitalization. The starting point was the last day of the acute ECT course during the period, and the end point was the day of relapse. Follow-up data were collected until September 2012. The patients were censored if they moved out of the hospital’s recruitment area, died, or had not been readmitted as of September 2012.

Statistical analyses

The cumulative probability of surviving without relapse was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier technique. Cox regression analyses were used to identify factors associated with relapse via univariate and multivariate analyses. Sex (male, female), the schizophrenia subtype (catatonic, noncatatonic), number of antipsychotic drugs after ECT (one, two, or more), main antipsychotics (FGA, SGA), and additional medication use (no, yes) were analyzed as categorical variables. The age at ECT, age at onset of illness, number of psychotic episodes, number of ECT sessions, CPZ equivalence, and BPRS score were analyzed as continuous variables. Univariate analyses were conducted, and factors with a trend toward statistical significance (P<0.10) were subsequently examined by a multivariate analysis. Two-tailed P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analyses were carried out on a personal computer using SPSS version 22.0 for Windows (IBM Japan Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Participants

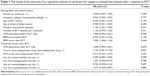

Fifty patients received acute ECT during the study period. Of these, 43 were responders and seven were nonresponders to the acute ECT course. The seven nonresponders included five patients with the paranoid, one patient with the catatonic, and one patient with the hebephrenic types of schizophrenia. There were significant differences in the response rate among the subtypes (responders/nonresponders: catatonic: 22/1, paranoid: 6/5, hebephrenic: 6/1, undifferentiated: 7/0, and residual: 2/0; P=0.013). However, there were no differences in the number of ECT sessions between the responders and nonresponders (P=0.673). A total of 43 responders were subsequently analyzed in this study. The patients’ characteristics are summarized in ( Table 1). There were no patients with a first episode; all of the patients had experienced two or more episodes.

Relapse-free rate

The mean follow-up period for all 43 patients was 15.8±20.3 months. During the follow-up, one patient died because of cancer. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve for the time to relapse is presented in (Figure 1). The relapse-free rates of the 43 patients at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years were 70.7%, 57.3%, and 48.4%, respectively. The median relapse-free period was 21.5 months.

Demographic and clinical factors

The factors that were significantly associated with relapse were the number of psychotic episodes (P=0.021) and the BPRS score after ECT (P=0.048) (Table 2). The number of ECT sessions tended to increase the risk of the relapse (P=0.091) (Table 2). The sex, subtype, age at ECT, age of onset of illness, CPZ equivalence before the acute ECT course, and the BPRS score before the acute ECT course were not significantly related to relapse.

Treatment factors

The use of a mood stabilizer tended to reduce the risk of relapse (P=0.058) (Table 2). Mood stabilizers were used mainly for drug-resistant, electroencephalographic abnormalities or for symptoms such as emotional instability. Among the 16 (37.2%) patients who used mood stabilizers, nine patients used lithium carbonate, six used sodium valproate, and one used carbamazepine. None of the evaluated patients took lamotrigine. No patients used a combination of mood stabilizers. The mean dose and blood levels of lithium carbonate were 500.0±200.0 mg/day and 0.49±0.16 mEq/L, respectively. The mean dose and blood levels of valproic acid were 833.3±196.6 mg/day and 59.0±18.1 μg/mL, respectively. The dose and blood levels of carbamazepine were 400 mg/day and 3.0 μg/mL, respectively. However, the patients were not randomized for the mood stabilizer treatment. The patients who received mood stabilizers had high BPRS scores before ECT (54.4±11.1 versus 46.9±9.9; P=0.028) and low BPRS scores after ECT (24.5±4.8 versus 30.9±10.3; P=0.009). The frequency of use of mood stabilizers was not significantly different between the catatonic and noncatatonic subtypes (22/21) (40.9% versus 33.3%; P=0.607).

The CPZ equivalence after ECT, the use of two or more antipsychotic drugs, and the use of SGA as the main antipsychotic were not associated with relapse. Fourteen (32.5%) patients received SGA monotherapy, three (7.0%) received FGA monotherapy, and 26 (60.5%) received multiple antipsychotic therapy. As the main antipsychotic after the acute ECT course, 35 (81.4%) patients used SGA and 8 (18.6%) patients used FGA. These included olanzapine (16; 37.2%), risperidone (13; 30.2%), aripiprazole (4; 9.3%), quetiapine (1; 2.3%), zotepine (1; 2.3%), haloperidol (5; 11.6%), and CPZ (3; 7.0%). Olanzapine and risperidone were compared with other antipsychotics, and no significant differences in the relapse rates were noted.

The use of an antidepressant, use of benzodiazepine, and the use of an anticholinergic were not associated with relapse (Table 2). A total of 35 (81.4%) patients received benzodiazepines, 19 (44.2%) received anticholinergics, and six (14.0%) received antidepressants.

As additional analysis, because 51% of patients constituted the catatonic subtype of schizophrenia, we tried to perform a similar analysis only by the type. However, it was not possible to perform the analysis for this small sample size.

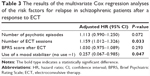

Multivariate analysis

The four factors with a trend toward statistical significance in the univariate analysis were examined by a multivariate analysis. The multivariate analysis showed that two factors significantly affected relapse: the number of ECT sessions and the use of a mood stabilizer after ECT (Table 3). The number of ECT sessions was associated with a significantly increased risk of relapse (hazard ratio =1.159; P=0.033), and patients who used a mood stabilizer were at a lower risk of relapse than were patients who did not (hazard ratio =0.257; P=0.047).

Discussion

Following a response to the acute ECT course, the relapse rates at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years were 29.3%, 42.7%, and 51.6%, respectively. Suzuki et al8 reported that seven (63.6%) of eleven patients with catatonic schizophrenia who responded to acute ECT relapsed during the 1-year follow-up, despite continuation of antipsychotics, and that all relapses occurred within 6 months. Hustig and Onilov7 reported that 17 (62.9%) of 27 treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients relapsed within 1 year after the application of ECT, and all relapses occurred within 8 months. The relapse rate in our study cannot be simply compared with those in past reports because of the differences in each study concerning factors such as patient subtype and definition of relapse. However, our study also showed that the relapses occurred soon after the ECT course, similar to the past reports, even if antipsychotic therapy was continued. It therefore seems that an intensive treatment strategy is necessary to prevent relapse, especially during the first year after ECT.

The first major finding of our current study was that additional mood stabilizer use was significantly related to a lower risk of relapse. There was a 74% risk reduction when adjunctive mood stabilizer therapy was used, compared to when no mood stabilizer was used. To the best of our knowledge, there have so far been no reports addressing the effect of mood stabilizers for schizophrenia after a response to ECT. Mood stabilizers may be helpful in specific subpopulations of schizophrenic patients, such as those with catatonic symptoms,11 anxiety depression,12 and hostility.13 ECT is also effective for patients with similar features, such as catatonic features, affective symptoms,5 tension, and hostility.14 Therefore, following an improvement of these symptoms by acute ECT, adjunctive mood stabilizer maintenance therapy may be a useful treatment strategy to support remission. Additionally, in a study of mood disorders,15 a combination of lithium and antidepressants had a marked advantage rather than antidepressants alone in terms of the time to relapse for patients with depression after a response to ECT. Mood stabilizers, such as lithium, may have a certain protective effect against relapse of not only depression but also schizophrenia after a response to ECT. However, with regard to the treatment strategies employed during the follow-up period, it is difficult to draw conclusions from retrospective studies, because the patients were not randomized, and different factors related to the selection of treatment might have influenced the results. It is possible that clinicians may choose to use mood stabilizers in schizophrenic patients with mood symptoms, who have been reported to tend to have a better outcome.16 Therefore, it cannot be denied that subpopulations of schizophrenia defined as having used mood stabilizers was less likely to relapse with or without treatment with ECT.

We were not able to detect an association between antipsychotic therapy (category, number, or daily use) or the use of antidepressants or benzodiazepine after ECT and relapse. In our study, because almost 60% of patients had polypharmacy with antipsychotics, and >80% of patients were taking additional psychotropic agents other than antipsychotics, the possibility of interactions between these drugs cannot be ruled out. A previous study17 comparing sulpiride, risperidone, and olanzapine in combination with c/m ECT revealed that risperidone and olanzapine were superior to sulpiride in terms of the clinical effects. In another study in adolescent subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders,18 the rate of rehospitalization was lower in patients treated with clozapine compared to that of the nonclozapine group (using other antipsychotics or benzodiazepines). Clozapine is used for intractable schizophrenia worldwide; however, it was not approved in Japan until 2009, and no patients received clozapine during the investigation period in the current study. Maintenance pharmacotherapy with clozapine seems to be an alternative strategy that should be examined in future studies.

The second finding of the current study was that the number of ECT sessions was significantly related to risk of relapse. Generally, the number of ECT sessions is not decided in advance of the treatment; rather, it is decided during the course based on the improvement in an individual’s symptoms. The general number of ECT sessions is 6–12; however, this differs by individual. According to a chart review of 79 cases, schizophrenic patients received between 2 and 26 sessions of acute ECT.1 When ECT was ineffective during the early sessions, the number of sessions was necessarily increased during that study, but it was not a control study. When more ECT sessions are necessary to improve symptoms, it may indicate that the patient is more intractable to treatment and may be more prone to relapse. Therefore, it is a compatible result that the patients received a greater number of ECT sessions and seem to easily relapse. When maintenance pharmacological prophylaxis alone is ineffective or not tolerated in the stable phase, the APA guidelines suggest that c/m ECT combined with an antipsychotic may be beneficial in patients who respond to acute ECT.19 Therefore, the number of acute ECT sessions could be one of the indicators for applying c/m ECT.

The findings of this study must be interpreted within the following limitations of this study: 1) this study was a naturalistic and retrospective study, not a randomized controlled trial; 2) the sample size was relatively small, and subjects were enrolled in one hospital; 3) the severity of the disease varied; 4) subjects may have had refractory properties because all of the patients had experienced two or more episodes of psychosis; 5) various maintenance pharmacotherapy was used because the medication was selected based on the attending physicians’ choices, rather than in a systematic manner; and 6) there was insufficient evaluation of some factors regarded as factors potentially related to the relapse of general schizophrenia, such as adherence to medicines, insight into the illness, adverse life events, the level of social support, premorbid psychosocial functioning, or expressed emotion because of the incomplete medical records. In addition, our data showed schizophrenia was of five subtypes, with 51% belonging to the catatonic type. In the past decade, catatonia has increasingly been recognized as a unique syndrome. An earlier review reported a great variation in the efficacy of ECT depending on the type of treatment setting and type of schizophrenia. The efficacy rate in catatonia is high compared to that in other types.2 It was desirable to separate the catatonia group from the other types and analyze the outcome itself, but it was not possible to perform the analysis due to the small sample size. Another concern is whether catatonia had an effect on the prevention of relapse by mood stabilizers after acute ECT in this study. Indeed, the patients who received mood stabilizers had higher BPRS scores before ECT and lower BPRS scores after ECT (see “Treatment factors” under Results section). However, mood stabilizers were used at approximately the same rate in the catatonia and noncatatonia groups (see “Treatment factors” under Results section). Therefore, catatonia may not influence the effects of mood stabilizers after acute courses of ECT.

A prospective and well-designed study with a large sample size is needed to evaluate effective medical treatments for preventing a relapse after acute ECT.

Conclusion

Our study on the relapse of schizophrenia after a response to acute ECT suggested that the number of ECT sessions may be related to the risk of relapse. On the other hand, adjunctive pharmacotherapy with mood stabilizers may be effective in preventing relapse.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Junko Tanaka for advising us about the statistical methods. We also appreciate all clinical contributions by Dr Hideo Kobayakawa, Dr Keigo Nakatsu, Dr Takashi Iwamoto, and Dr Kei Itagaki. Dr Chiyo Shibasaki is now affiliated with Mihara Hospital and is indebted to the hospital for continuing support.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Kristensen D, Bauer J, Hageman I, Jorgensen MB. Electroconvulsive therapy for treating schizophrenia: a chart review of patients from two catchment areas. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261:425–432. | ||

Zervas IM, Theleritis C, Soldatos CR. Using ECT in schizophrenia: a review from a clinical perspective. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13:96–105. | ||

Leiknes KA, Jarosh-von Schweder L, Hoie B. Contemporary use and practice of electroconvulsive therapy worldwide. Brain Behav. 2012;2:283–344. | ||

Takebayashi M. The development of electroconvulsive therapy in Japan. J ECT.2010;26:14–15. | ||

Kristensen D, Jørgensen MB. Treatment of schizophrenia with electroconvulsive therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2011;8:53–56. | ||

American Psychiatric Association. The Practice of Electroconvulsive Therapy: Recommendations for Treatment, Training, and Privileging (A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association).2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2001. | ||

Hustig H, Onilov R. ECT rekindles pharmacological response in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:521–525. | ||

Suzuki K, Awata S, Matsuoka H. One-year outcome after response to ECT in middle-aged and elderly patients with intractable catatonic schizophrenia. J ECT. 2004;20:99–106. | ||

Tandon R, Belmaker RH, Gattaz WF, et al. Section of Pharmacopsychiatry, World Psychiatric Association. World Psychiatric Association pharmacopsychiatry section statement on comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;100:20–38. | ||

Petrides G, Fink M. The “half-age” stimulation strategy for ECT dosing. Convuls Ther. 1996;12:138–146. | ||

Padhy SK, Subodh B, Bharadwaj R, Arun Kumar K, Kumar S, Srivastava M. Recurrent catatonia treated with lithium and carbamazepine: a series of 2 cases. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord.2011;13:CC.10l00992. | ||

Terao T, Oga T, Nozaki S, et al. Lithium addition to neuroleptic treatment in chronic schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Acta Psychiatr Scand.1995;92:220–224. | ||

Citrome L, Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wozniak P, Kochan LD, Tracy KA. Adjunctive divalproex and hostility among patients with schizophrenia receiving olanzapine or risperidone. Psychiatr Serv.2004;55:290–294. | ||

Chanpattana W, Sackeim HA. Electroconvulsive therapy in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: prediction of response and the nature of symptomatic improvement. J ECT. 2010;26:289–298. | ||

Sackeim HA, Haskett RF, Mulsant BH, et al. Continuation pharmacotherapy in the prevention of relapse following electroconvulsive therapy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1299–1307. | ||

Davidson L, McGlashan TH. The varied outcomes of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42:34–43. | ||

Ravanić DB, Pantović MM, Milovanović DR, et al. Long-term efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy combined with different antipsychotic drugs in previously resistant schizophrenia. Psychiatr Danub. 2009;21:179–186. | ||

Flamarique I, Castro-Fornieles J, Garrido JM, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy and clozapine in adolescents with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: is it a safe and effective combination? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:756–766. | ||

Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, McGlashan TH, Miller AL, Perkins DO. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1–56. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.