Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Exploring the Relationship Between Work–Family Conflict, Family–Work Conflict and Job Embeddedness: Examining the Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion

Authors Dukhaykh S

Received 29 September 2023

Accepted for publication 16 November 2023

Published 30 November 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 4859—4868

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S429283

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Suad Dukhaykh

Management Department, College of Business, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11451, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Suad Dukhaykh, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to examine the relationships between family–work conflicts, work–family conflicts, emotional exhaustion, and job embeddedness. Emotional exhaustion was hypothesized to mediate relations between family–work conflicts, work–family conflicts and job embeddedness.

Methods: An online questionnaire was distributed to collect the data. The sample consisted of 264 women aged 18 years and older who work in private sector in Saudi Arabia. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), common method bias (CMB), and structural equation modeling (SEM) were conducted using AMOS (Version 28).

Results: The results show that emotional exhaustion functions as a full meditator of the relationship between work–family conflicts, family–work conflicts and job embeddedness. Specifically, women who experience work and family conflicts are unable to balance heavy workloads are emotionally exhausted which in turn affects their job embeddedness.

Conclusion: The study emphasizes the negative effects of both work-to-family and family-to-work-life spillover that result in unfavorable psychological states for female employees. Therefore, it is essential for organizations to have interventions that support balancing the demands of family and work. Organizations need to consider how much control an employee has over the time and location of their job. Organizations must also provide clear procedures for handling flexible work schedules and part-time employment.

Keywords: family–work conflict, emotional exhaustion, work–family conflict, job embeddedness, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Work–family and family–work conflicts are the main source of stress for many employees.1,2 The two most important domains of life for most individuals are family and work, and making a balance between the two domains has been recognized as a significant social issue. The issue of conflicts between work and family domains has stressed the importance for many researchers to investigate the conflicts.1,3 The family role is expected to suffer if an employee dedicates more time in work and energy to the work role.

Heavy workload has several consequences on the workers’ overall physical and mental health, especially women who face many challenges in both work and family. Work and family conflict can be defined as a challenging situations caused by heavy workloads that spell over non-work domains such as family, health, and education.4 These demanding and stressful situations engender emotional exhaustion.5

A plethora of research studies have examined the work–family conflict and family–work conflict over the past couple of decades, and the findings illustrate that the work–family conflict and family–work conflict have contributed to various adverse health effects such as fatigue, emotional exhaustion, stress, work and life dissatisfaction.6–11 Surprisingly, despite this, little is known about work-related outcomes such as job embeddedness and the mediating role of emotional exhaustion.

Grounded in this backdrop, the aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between family–work conflict and work–family conflict on job embeddedness mediated by emotional exhaustion among Saudi working women. The rights of Saudi women have expanded under the current leadership in Saudi Arabia. Saudi women are more involved in many fields and their participation in society, government, and business have been increased. Vision 2030 aims to create one million jobs for women.12 In 2021, Saudi women’s participation rate in the workforce has grown from 20 percent in 2018 and reached 33 percent by the end of 2020, according to the General Authority for Statistics. This indicates that the share of working Saudi women increased by 65 percent in only two years.

Considering the above, this study has several contributions. First, work–family conflict and family–work conflict are frequently experienced by working women in a very traditional gender-role-oriented culture where women assume to peruse double jobs. Historically, Saudi women’s education and employment opportunities have been restricted to primarily female-associated, sex-segregated occupations and short working hours, such as teaching and nursing.13 Saudi women’s entry into many professions, such as engineering, technology, and business, is a relatively recent. Therefore, the results of this research would stress the importance of providing structural interventions in organizations that target working women in order to reduce work–family conflict.

Second, the outcomes of job embeddedness have been examined by a substantial amount of research, such as voluntary turnover, turnover intentions, and performances.14–17 However, the antecedents of job embeddedness have not been sufficiently studied.18,19 Limited empirical research has investigated organizational and/or individual factors that influence employees’ job embeddedness. For example, Bergiel et al20 found that opportunity for growth, compensation, and supportive supervisor influenced job embeddedness. Ng and Feldman18 demonstrated that social networking behaviors and contract non-replicability fully mediate the association between locus of control and job embeddedness. Sun et al17 found that psychosocial capital affected job embeddedness in China among nurses. The abovementioned research delineates variables improving job embeddedness.However, few empirical studies pertaining to health and social related factors reducing employees’ job embeddedness.19

Conceptual Background and Hypotheses Development

Work–Family Conflict, Family-Work Conflict and Emotional Exhaustion

Work–family conflict defines as “a form of interrole conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to, and strain created by the job interfere with performing family-related responsibilities”.3 Family–work conflict has been defined as “a form of interrole conflict in which the general demands of, time devoted to, and strain created by the family interfere with performing work-related responsibilities”3. With time, a person’s effort to meet the demands of work role depletes personal resources, creating emotional exhaustion.21–24 Excessive work and family demands elevate emotional exhaustion since emotional exhaustion is a response to heavy workloads or excessive demand. Employees may experience emotional exhaustion when they are trying to manage issues related to work and family.

Working women are more vulnerable to work–family conflicts; women have double roles to play in their lives by performing full-time jobs and their role in the home as a housewife or a homemaker, which causes immense stress and strain in terms of balancing time and energy.25 Furthermore, besides balancing home and workplace, women also encounter conflicts between personal and social requirements; thus, they are more at risk of emotional exhaustion and fatigue than men.26 Hence, the following hypotheses have been developed in line with the existing literature.

H1. Work-family conflict (Ha1) and family to work conflict (Ha2) are positively related to emotional exhaustion.

Emotional Exhaustion and Job Embeddedness

Job embeddedness can be defined as several factors or forces that affect an employee’s decision to leave or stay the job.27 Job embeddedness refers to individuals’ attachment to the organization or job and employees’ perception of person–job fit, and it can be linked to the sacrifice related to the social and financial costs of leaving the job or organization.14 Hence, it can be expressed as a positive state for both individual and organizations since employees with high levels of job embeddedness are expected to perform better in their jobs, tend to exhibit more positive attitudes, and are not prone to absenteeism or turnover intention.28 Many researchers have investigated more in the antecedents of job embeddedness due to its importance as a workplace variable but with limited individual factors.

Affective force is considered one of the attachment and withdrawal motivational forces.29 Affective responses represent employees’ psychological discomfort or comfort with respect to their organization or job. When an employee experiences the state of discomfort, he/she is more likely to have turnover intentions to leave or display quitting intentions, while others who experience comfort are more likely to stay in the job or organization.29 Mitchell et al30 and Schaufeli and Bakker31 suggest that intention to leave the organization can be affected by low job embeddedness as well as a disengaged workforce. Therefore, when employees are emotionally exhausted, feel that their emotional resources are depleted, and are devoid of energy, they appear to have intentions to quit as a result of the discomfort in the organization or the job due to high levels of emotional exhaustion. These circumstances lead to lower job embeddedness, and therefore, the employees will be more likely to display tardiness, absenteeism, or intention to quit c.f,16,19 Based on the above, the following hypothesis is developed:

H2. Emotional exhaustion is negatively related to job embeddedness.

Mediating Effect

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model has been widely applied in occupational stress research to show how the condition of work environment affect employees’ mental health and several job-related outcomes, such as organizational engagement, commitment and overall job performance.32–34 The JD-R model postulates that job resources as well as job demands are the most important work related characteristics, despite the fact that every work environment has unique characteristics associated with the work domain.33 Work–family conflict, family-work conflict, perceptions of organizational politics, and emotional dissonance are examples of job demands. On the other hand, rewards, supervisor support, feedback, opportunity for training and development are job resources’ examples.

The JD-R model represents two divergent processes: the first one is the health impairment process, and the second one is the motivational process.33,34 The health impairment process is associated with the chronic job demands that may reduce employees’ emotional and physical resources, leading to emotional exhaustion, burnout, and negative health and job outcomes.33,34 The motivational process, on the other hand, explains the motivational role of job resources, which has a positive influence in terms of reducing job demands and fostering learning, growth and development of employees.33,34 To be more specific, employees who are frequently faced with work–family conflict and family-work conflict feel emotionally exhausted due to heavy work demand, which, in turn, influences employees level of job embeddedness. When employees feel that they are unable to overcome immense job demands and unable to manage family and work roles due to excessive work and family conflicts, they are more likely to experience a psychological response to the heightened level of stress which called emotional exhaustion. Employees are less likely to overcome issues arising from strain and stressors without links between them and other people, such as managers and colleagues inside the organization. Employees who struggle with strain and stressors recognize that their career goals, skills and personal values do not fit with the excessive demands. Thus, the elevated levels of stressors and strain cause employees to sacrifice opportunities and benefits in the organization. As a result, they will less embedded due to negative experiences and unfavorable work situations by reducing their work effort, paying less attention, or considering leaving the organization.19 Therefore, this study uses JD-R model as the theoretical framework to propose that emotional exhaustion is a mediator of the effects of conflict in the work–family interface on job embeddedness. Hence the following hypotheses is developed:

H3. The negative relation between (work-to-family, H3a; and family-to-work, H3b) and job embeddedness is mediated by emotional exhaustion.

Methodology

Sample and Data Collection

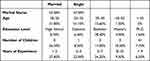

A Saudi Arabian native was invited to translate the English version of the questionnaire to Arabic using forward translation. For back translation, we have selected two bilingual researchers to perform the back translation to ensure that there are no errors in meaning cf.,35 The accuracy of the survey was tested in a pilot study with 65 participants, all of whom understood the questions; this sample was left out of the study’s actual survey participants. Sample for the current study was women who work in the private sector specifically female employees belonging to Information Technology, Bank and Retail sector located in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The researcher contacted HR managers of nine organizations, and informed them about purpose of the research. Three IT organizations, two retail companies, three banks agreed to distribute the online survey to their full-time female employees only. Out of the 312-email sent to respondents with the link of the questionnaire, 264 were returned (response rate of 85). The data were collected between March and May 2022. The respondents consisted of only women aged 18 years and older who work in the private sector in Saudi Arabia. The demographics of the research sample are illustrated in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Demographics of Research Sample (N = 264) |

Measures

A structured online survey was used to gather data, and the following variables were measured via the survey’s questions. Work–family conflict and family–work conflict was measured using the ten-item scales ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5), developed by Netemeyer et al.3 A sample item of the work–family conflict scale includes “The demand of my work interferes with my family life”. A sample item of family–work conflict consists of “family related strain interferes with my ability to perform job related duties”. For emotional exhaustion, a subscale of the General Burnout Questionnaire was used. It was measured and assessed by the five-item work exhaustion frequency scale ranging from “never” (0) to “daily” (5).36 Participants were asked to report their experiences “in the past month.” A sample item of emotional exhaustion consists of “because of my job, I feel emotionally drained”. Job embeddedness we assessed using seven items scale developed by Crossley et al.37 Respondents were asked to report their level of agreement on a five-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). A sample item of job embeddedness includes “I feel connected to my organization”.

Measurement Model Result

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

AMOS (Version 28.0), a covariance-based SEM method that performs the maximum likelihood approach, was used to create the measurement model. No unidirectional path between any latent was specified in the CFA model. However, a covariance model was assessed in which each latent variable was correlated with all other latent variable.

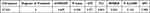

In a single confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the psychometric properties of the six latent constructs were simultaneously assessed. Multiple indices should typically be taken into account at once when assessing the model fit. The outcomes showed that the model has a decent model fit. Standard errors and residuals showed no issues. Table 2 demonstrates that a good model fit was reached.38

|

Table 2 Model Fit |

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

The measuring model has been evaluated for convergent validity using the following three criteria: (1) the factor loadings of the CFA must be greater than 0.5;39 (2) CR must be greater than 0.7; and (3) each construct’s average variance extracted (AVE) must be above 0.5.40 These criteria were suggested by Bagozzi and Yi.41 The convergent validity for the hypothesized constructs of this model is sufficient, as demonstrated in Table 3. Fornell and Larcker40 suggest that the AVE of the construct should exceed the correlation coefficients of the construct to have adequate discriminant validity.

|

Table 3 Reliability, Convergent Validity, and Discriminant Validity |

The matrix of correlations between the constructs used in this study is displayed in Table 3. All of the constructs in this study’s measurement model differ from one another, which suggests that they all have sufficient discriminant validity. The discriminating validity of the measurement model has also been measured by looking at correlations between latent constructs. As a sign of inter-correlated constructs, high-value correlations over 0.9 or over 0.85 should be taken care of.39,42 Because of this, the measurement model used in this study has acceptable reliability as well as convergent and discriminant validity.38

Common Method Bias

When only one data collection is used, research is particularly prone to common method bias.43 Three nested models—the unconstrained model, the equal loadings model, and the equal to zero loadings model—were established after a common latent factor (CLF) was added. According to the level of significant in the p-values, the unrestricted model fits the data better than the nested models. These results therefore imply that common method bias is significant. The unconstrained model was the one that fit the data the best among the three models. Hence, the CLF was retained when perfuming the structural model and the composites were imputed from factor scores.44

Structural Model Result

Descriptive Statistics

Table 4 illustrates the means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlation between the study variables. The reliabilities of all variables have were above.7.39

|

Table 4 Means, Standard Deviations, Cronbach’s Alphas, and Intercorrelations Among Study Variables |

Direct Effects Within the Structural Equation Model

Figure 1 illustrates that Hypotheses (H1a), (H1b), and (H2) are supported. Work–family conflict is positively related to emotional exhaustion (β = 0.712, p < 0.001). Family–work conflict is positively related to emotional exhaustion (β = 0.172, p < 0.05). Emotional exhaustion has a negative effect on job embeddedness (β = −0.233, p < 0. 01). The direct affect from work–family conflict to job embeddedness is positive and supported (β = 0.403, p < 0. 001). The relationship between family–work conflict and job embeddedness is not statistically significant (β = −0.041, p > 0. 05). Table 5 demonstrates that a good model fit was reached.38

|

Table 5 Model Fit |

|

Figure 1 Hypothesized model results. Notes: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. |

MediationTtesting

Bootstrapping method suggested by Hayes was used.45 In order to avoid the non-normal distribution, two thousand bootstrapping was performed.The results are considered significant at 95 percent CI. As illustrated in Table 6, the indirect effect of work–family conflict to job embeddedness via emotional exhaustion is β = −0.166, p < 0.05 (H3a). Furthermore, the indirect effect of family–work conflict to job embeddedness via emotional exhaustion is β = −0.040, p < 0.05. (H3b)

|

Table 6 Mediation Testing Results |

Discussion

Theoretically driven hypotheses were examined on how emotional exhaustion mediate the relations between work–family conflicts, family–work conflicts, and job embeddedness. Consistent with the hypotheses and in line with the previous research,16,19,26,28,31–34 the results show that work–family conflict and family–work conflicts have a significant effect on emotional exhaustion, emotional exhaustion is negatively related to job embeddedness, and the conditional indirect effect of work–family conflict and family–work conflicts to job embeddedness via emotional exhaustion are negative and significant. Therefore, the rise in work-family and family-work conflicts may not directly result in a decrease in job embeddedness. Instead, it can cause an increment in emotional exhaustion and the increase level of emotional exhaustion caused by family-work and work-family conflicts would indirectly result in reducing women’ job embeddedness.

The results are similar to the study by Schaufeli and Bakker,31 who found that work–life conflict consumes employees’ physical and mental resources, resulting in increased emotional exhaustion, which leads to decreasing job embeddedness. Similar to this, researchers have postulates that running out of resources (such as energy, time and effort) frequently causes people to have negative perceptions of their jobs, experience a gradual deterioration in workplace well-being, and eventually become less embedded in their jobs.46,47

According to Schaufeli and Bakker,31 demands are “things that have to be done”, whether in the personal or professional sphere, requiring great efforts that may have negative outcomes including anxiety, exhaustion and depression. The effects of a person’s excessive resource dwindling are particularly profound in the case of female employees. Quinn and Smith48 have found that women are more likely to have family–work conflicts and work–family conflicts because of their job conditions; specifically, women have less control/ authority over the job demands, leading to increased stress and frustration. Additionally, a lack of support from spouses in regard to family responsibilities makes it challenging for female employees to balance multiple obligations, responsibilities and time conflicts, leading to mental stress.

The number of working women and dual-career couples in Saudi Arabia is on the rise at an unprecedented rate. In such situations, domestic responsibilities such as childcare may make it harder for female employees to manage dual responsibilities, leading to situations where work-life conflict and family-work conflict occur. Conflicts may require women to choose between continuing their careers or prioritizing family care responsibilities. The rising complexity of work-family conflicts affects women more than men, having a negative impact on their health such as stress and emotional exhaustion.49 This is because traditionally, women’ main role is to take care for the family while men tend to be in charge of the roles related to the work. Consistent with the health impairment process of the JD-R model e.g.,33 working women experience a work-family interface that depletes their physical and emotional resources and causes high levels of emotional tiredness, which in turn affects how embedded they are in their jobs.

Practical and Theoretical Implications

The study emphasizes the negative effects of both work-to-family and family-to-work-life spillover that result in unfavorable psychological states for female employees. Therefore, it is essential for organizations to have interventions that support balancing the demands of family and work. This aspect is critical for female employees. Organizations need to consider how much control an employee has over the time and location of their job. Organizations must also provide clear procedures for handling flexible work schedules and part-time employment. Last but not least, women need to understand that they can balance motherhood with a successful profession. They must have control over their expected role from both work and life spheres.

At a theoretical level, the study makes several contributions to the literature on the JD-R model through the greater understanding of job demand and its association with adverse health and job-related outcomes.33,34 Additionally, the study suggests that job embeddedness is influenced by WFC and FWC indirectly through emotional exhaustion which means that WFC and FWC have no influence on lowering female employee job embeddedness directly. Lastly, exploring the association between the selected variables through mediation analysis further elucidates the pathways contributing to negative health and job-related outcomes for women in Saudi Arabia.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The present study has some limitations. First, inferring causality was not possible due to the cross-sectional research design; thus, future research must use a longitudinal research design to investigate the causal effects of work–life conflict and family–work conflict on employees’ job embeddedness mediated by emotional exhaustion. Second, the research sample was only women; it would be beneficial to take a sample of men and women and compare the results. Third, self-report measure was used to analyze the date; therefore, common method bias is another limitation of this study. Forth, it will be beneficial to examine the role of family support and organizational support as moderating variables. Finally, the sample used in this study has targeted female employees from Saudi Arabia; future studies involving female employees from different countries might be interesting and help in term of generalizing the findings.

Conclusion

The present study examined a research model that investigated the role of emotional exhaustion as a mediator of the impacts of work-family conflict and family-work conflict on job embeddedness. The hypotheses were tested through data gathered from female employees working in the private sector in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The results indicated that all hypotheses received empirical support. Work-family conflict and family-work conflict influenced job embeddedness only via the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. It is crucial for organizations to take into account the establishment of a family-supportive work environment and to offer mentors who can provide professional assistance to female employees.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of King Saud University No.: KSU-HE-21-822, Date 08/12/2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Funding

This research is supported by research supporting program (RSPD2023R1023).

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Rev. 1985;10(1):76–88. doi:10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

2. Kahn RL, Wolfe DM, Quinn RP, Snoek JD, Rosenthal RA. Organizational Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity. Oxford, England: John Wiley; 1964:xii, 470–xii, 470.

3. Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R. Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):400–410. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400

4. Keeney J, Boyd EM, Sinha R, Westring AF, Ryan AM. From “work–family” to “work–life”: broadening our conceptualization and measurement. J Vocational Behavi. 2013;82:221–237. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2013.01.005

5. Cordes CL, Dougherty TW. A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad Manage Rev. 1993;18(4):621–656. doi:10.5465/amr.1993.9402210153

6. Adams GA, King LA, King DW. Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work–family conflict with job and life satisfaction. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):411–420. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.411

7. Calisir F, Gumussoy CA, Iskin I. Factors affecting intention to quit among IT professionals in Turkey. Personnel Rev. 2011;40(4):514–533. doi:10.1108/00483481111133363

8. Hang-yue N, Foley S, Loi R. Work role stressors and turnover intentions: a study of professional clergy in Hong Kong. Int J Human Resource Manage. 2005;16(11):2133–2146. doi:10.1080/09585190500315141

9. Lambert EG, Qureshi H, Frank J, Keena LD, Hogan NL. The relationship of work-family conflict with job stress among Indian police officers: a research note. Police Practice Res. 2017;18(1):37–48. doi:10.1080/15614263.2016.1210010

10. Lingard H, Francis V. The work‐life experiences of office and site‐based employees in the Australian construction industry. Construction Manage Economics. 2004;22(9):991–1002. doi:10.1080/0144619042000241444

11. Mansour S, Tremblay D-G. Work–family conflict/family–work conflict, job stress, burnout and intention to leave in the hotel industry in Quebec (Canada): moderating role of need for family friendly practices as “resource passageways”. Int J Human Resource Manage. 2018;29(16):2399–2430. doi:10.1080/09585192.2016.1239216

12. Vietor RHK, Sheldahl-Thomason H. Saudi Arabia: Vision 2030. Harvard Business Publishing Education. Harvard Business School Case 718-034; 2018.

13. Al Munajjed M. Women’s employment in Saudi Arabia: a major challenge; Booz & Company. Riyadh; 2010. Available from: https://www.arabdevelopmentportal.com/sites/default/files/publication/235.womens_employment_in_saudi_arabia_a_major_challenge.pdf.

14. Halbesleben JRB, Wheeler AR. The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work Stress. 2008;22(3):242–256. doi:10.1080/02678370802383962

15. Karatepe OM, Ngeche RN. Does job embeddedness mediate the effect of work engagement on job outcomes? A study of hotel employees in Cameroon. J Hospitality Marketing Manage. 2012;21(4):440–461. doi:10.1080/19368623.2012.626730

16. Lee TW, Mitchell TR, Sablynski CJ, Burton JP, Holtom BC. The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences, and voluntary turnover. Acad Manage J. 2004;47(5):711–722. doi:10.5465/20159613

17. Sun T, Zhao XW, Yang LB, Fan LH. The impact of psychological capital on job embeddedness and job performance among nurses: a structural equation approach. J Adv Nursing. 2012;68(1):69–79. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05715.x

18. Ng TWH, Feldman DC. Locus of control and organizational embeddedness. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2011;84(1):173–190. doi:10.1348/096317910X494197

19. Holtom BC, Burton JP, Crossley CD. How negative affectivity moderates the relationship between shocks, embeddedness and worker behaviors. J Vocational Behavi. 2012;80(2):434–443. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.12.006

20. Bergiel EB, Nguyen VQ, Clenney BF, Stephen Taylor G. Human resource practices, job embeddedness and intention to quit. Manage Res News. 2009;32(3):205–219. doi:10.1108/01409170910943084

21. Burke RJ, Greenglass ER. Hospital restructuring, work-family conflict and psychological burnout among nursing staff. Psychol Health. 2001;16(5):583–594. doi:10.1080/08870440108405528

22. Kinnunen U, Vermulst A, Gerris J, Mäkikangas A. Work–family conflict and its relations to well-being: the role of personality as a moderating factor. Personality Individual Differences. 2003;35(7):1669–1683. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00389-6

23. Posig M, Kickul J. Work‐role expectations and work family conflict: gender differences in emotional exhaustion. Women Manage Rev. 2004;19(7):373–386. doi:10.1108/09649420410563430

24. van Daalen G, Willemsen TM, Sanders K, van Veldhoven MJPM. Emotional exhaustion and mental health problems among employees doing “people work”: the impact of job demands, job resources and family-to-work conflict. Int Arch Occupational Environ Health. 2009;82(3):291–303. doi:10.1007/s00420-008-0334-0

25. Kenney JW, Bhattacharjee A. Interactive model of women’s stressors, personality traits and health problems. J Adv Nursing. 2000;32(1):249–258. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01464.x

26. Gyllensten K, Palmer S. The role of gender in workplace stress: a critical literature review. Health Education J. 2005;64(3):271–288. doi:10.1177/001789690506400307

27. Dawley DD, Andrews MC. Staying put: off-The-job embeddedness as a moderator of the relationship between on-The-job embeddedness and turnover intentions. J Leadership Org Studies. 2012;19(4):477–485. doi:10.1177/1548051812448822

28. Kanten P, Kanten S, Gurlek M. The effects of organizational structures and learning organization on job embeddedness and individual adaptive performance. Procedia Economics Finance. 2015;23:1358–1366. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00523-7

29. Maertz CP Jr, Campion MA. Profiles in quitting: integrating process and content turnover theory. Acad Manage J. 2004;47(4):566–582. doi:10.5465/20159602

30. Mitchell TR, Holtom BC, Lee TW, Sablynski CJ, Erez M. Why people stay: using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Acad Manage J. 2001;44(6):1102–1121. doi:10.5465/3069391

31. Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J Organizational Behav. 2004;25(3):293–315. doi:10.1002/job.248

32. Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. The crossover of burnout and work engagement among working couples. Human Relations. 2005;58(5):661–689. doi:10.1177/0018726705055967

33. Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The job demands‐resources model: state of the art. J Manage Psychol. 2007;22(3):309–328. doi:10.1108/02683940710733115

34. Llorens S, Bakker AB, Schaufeli W, Salanova M. Testing the robustness of the job demands-resources model. Int J Stress Manage. 2006;13(3):378–391. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.13.3.378

35. Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cultural Psychol. 1970;1(3):185–216. doi:10.1177/135910457000100301

36. Schaufeli W, Leiter M, Kalimo R. The General Burnout Inventory: a self-report questionnaire to assess burnout at the workplace. In

37. Crossley CD, Bennett RJ, Jex SM, Burnfield JL. Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(4):1031–1042. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1031

38. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

39. Hair JF Jr, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate Data Analysis.

40. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104

41. Bagozzi RP, Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Academy Marketing Sci. 1988;16(1):74–94. doi:10.1007/BF02723327

42. Kline RB. Software review: software programs for structural equation modeling: amos, EQS, and LISREL. J Psychoeducational Assessment. 1998;16(4):343–364. doi:10.1177/073428299801600407

43. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

44. Serrano Archimi C, Reynaud E, Yasin HM, Bhatti ZA. How perceived corporate social responsibility affects employee cynicism: the mediating role of organizational trust. J Business Ethics. 2018;151:907–921. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-3882-6

45. Hayes A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford; 2013.

46. Amstad FT, Meier LL, Fasel U, Elfering A, Semmer NK. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J Occupational Health Psychol. 2011;16(2):151–169. doi:10.1037/a0022170

47. Nohe C, Meier LL, Sonntag K, Michel A. The chicken or the egg? A meta-analysis of panel studies of the relationship between work–family conflict and strain. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100(2):522–536. doi:10.1037/a0038012

48. Quinn MM, Smith PM. Gender, work, and health. Ann. Work Exposures Health. 2018;62:389–392. doi:10.1093/annweh/wxy019

49. Blanch A, Aluja A, Gyllensten K, Palmer S. Social support (family and supervisor), work–family conflict, and burnout: sex differences. Human Relations. 2012;65(7):811–833. doi:10.1177/0018726712440471

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.