Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 10

Explaining professionalism in moral reasoning: a qualitative study

Authors Kamali F, Yousefy A , Yamani N

Received 13 August 2018

Accepted for publication 23 January 2019

Published 26 June 2019 Volume 2019:10 Pages 447—456

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S183690

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Farahnaz Kamali, Alireza Yousefy, Nikoo Yamani

Department of Medical Education, Medical Education Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Purpose: Professionalism is one of the most fundamental elements in judgment and moral reasoning and also an essential skill accompanied by other technical and scientific skills in the medical staff. Awareness of ethical aspects involves the clinical decision-making for patients. Therefore, this study aimed at explaining the role of professionalism in moral reasoning.

Patients and methods: This qualitative study was conducted on 17 faculty members and clinical students of medicine department. The participants were selected through purposive sampling method, and the data were collected via semistructured interviews after getting informed consent. Then, data were analyzed using conventional content analysis method.

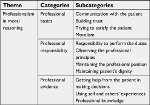

Results: Three main categories and eleven subcategories were classified as follows: professionalism principles with four subscales such as communication with patients, trust building, satisfying the patients, and moralism; professional responsibility with four subscales such as fulfillment of duties, commitment to professional rules, maintaining professional position, and dignity of the patient; professional evidence with three subscales based on data analysis such as patient’s participation in decision-making, personal and other’s experiences, and professional knowledge.

Conclusion: Training qualified people in medicine is one of the important missions of the professors. Improving the professionalism in students enables them in moral reasoning. Training professional principles, responsibility, and using professional evidence are the strategies used for job commitment in moral reasoning, and emphasis on how to train medical ethics will support graduates.

Keywords: moral reasoning, professionalism, medicine, qualitative study, ethical decision making, clinical practice

Introduction

Medical ethics and cultural sensitivities have recently attracted the attention of nations and are essential elements in medical education.1 Significant developments in medical sciences and modern biotechnology promoted an ever-increasing need for discussing ethical issues and decision-making process.2 In the competitive and developing society of the current century, moral judgment and critical thinking skills play a key role in shaping and promoting the society.3

Paul and Elder believe that moral judgment and decision-making are the vital skills relied on ethical principles and are essential to build an ethical-oriented community; such skills are directly related to the level of moral evolution in the community members.4 Although observance of ethical codes is necessary in all occupations, it is of great importance in the medicine due to its effect on patients’ recovery.5 Kollemorten et al also believe that moral reasoning is the main art of clinical decision-making; they stated that value judgments are made based on ethical decision-making, in which the acceptable actions should be taken based on the ethical norms and rules of decision-making by assessing the consequences of a decision and the duties of a decision maker.6–10

Although technological developments contribute to clinical judgment, the promotion of moral aspects and professionalism require specific technical knowledge and competence and are the necessary skills along with other scientific and technical capabilities to make the appropriate decision in a medical team.11 The essential requirements in medical education11–13 include promoting behaviors and positive attitudes in physicians toward the community and patients and also prioritizing the patient’s interest by developing the infrastructures to fulfill the professionalism in clinical practices11–13 that is naturally the basis of medical ethics and professionalism, which involves the patient in the decision-making process.14

Nowadays, observing the ethics code in patient care becomes a complicated and difficult task, and other traditional and guideline-oriented approaches are inefficient in this field. Meanwhile, those who cannot integrate such norms with personal values will become morally stressful and inadequate to the patient care and make them uncertain, which puts them in an uncertain status.9,14 Of course, such uncertain status is due to inadequate knowledge and training in ethics and the specific conditions of the workplace.15 Dierckx de Casterlé et al believe that promoting the ethical behaviors in complex workplaces is less likely, and studies show that such circumstances make nurses involve indirectly or even rarely in moral reasoning.16 Therefore, the need to educate, revive, and promote professional ethics is a fundamental requirement, and providing ethical guidelines for proper decision-making is inevitable.17,18 Nevertheless, it is important to consider the ethical reasoning as one of the most important element in professionalism.

The required conditions to convert moral reasoning into ethical behavior are also important, and merely high level of moral reasoning does not always guarantee the moral and professional care.14 Hence, training qualified people in medicine with analytical skills in solving problems and ethical dilemma seems essential.19 Studies have also indicated that students with higher scores in medical ethics show more commitment to clinical decisions.20 It is emphasized that the promotion of ethical and professional skills needs their recognition and interaction with other variables, and professors play an important role in achieving higher levels of thinking and giving opportunities to discuss to the students.3 This is definitely impossible via teaching a series of ethical codes but can be achieved through empowering the students to analyze, rethink their personal feelings and experiences, and train ethical standards and professional development.21 Glick also believes that the ultimate goal of teaching medical ethics is to enable the students to solve ethical issues, create moral sensitivity and ethical performance, and prevent damage to patients.22 Since the students’ ethical and professional development usually happens in the classroom and training the ethical codes is not sufficient, thus to fill this gap, teachers should assess students’ capabilities and moral reasoning approaches before the graduation because physicians cannot solve medical problems without benefitting from problem-solving skills.23 Since ethical decision-making strategies are completely personal processes and defined as black boxes, there are a lot of disagreements among experts on issues such as the objectives emphasized in medical ethics, the proper methods of teaching and learning, the assessable implications in evaluation, and the moral reasoning status.24 But focusing on accessible factors is highlighted by everyone.25

On the contrary, despite the importance of observing the professionalism in clinical practices, current efforts to help students manage ethical riddles are not enough and do not enable them to manage the coming ethical issues,20 and it is the time to train the students widely to fulfill our duty for empowering the next generation.

Since the sociocultural and individual differences in various communities play a pivotal role in the development of decision-making process,28–30 it is expected that the Iranian society, as a religious community bound to the ethical principles, make all decisions based on the Islamic rules; because in Islamic trainings, adoring the human beings with moral virtues is one of the fundamental goals. Thus, this study aimed at clarifying the personal experiences of professionalism in Iranian society to make the patients deeply understand the professional ethics in moral reasoning, although in qualitative studies and not in quantitative ones.31

Patients and methods

In this study, to access the participants’ experiences in moral reasoning, a contractual content analysis obtained from a qualitative study was employed.

Participants

According to the qualitative design of this study, the samples were selected based on the objectives, and the purposive sampling method was done. Nursing, midwifery, medical, and clinical assistance students as well as the faculty members (gynecology, pediatric, oncology, rheumatology, emergency, infectious diseases, and nephrology) with different demographic information (gender, age, experiences, and specialty) were selected. Seventeen personal interviews were done from Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Bushehr University of Medical Sciences. At the beginning of the study, the objectives, mode of interview, types of questions, and the authority to exclude from the interview were explained to the participants. After obtaining the informed consent from the participants, the time and place of interview were determined unanimously. They were assured about the confidentiality of their information as well as anonymity of their datasheets.

Data collection

Data were collected through deep semistructured interviews after the approval of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. It is a proper method due to the complexity of the study topic.32 The study was done in participants’ workplace or universities. After signing the informed consent, the participants answered the questions and recorded their voice. The questions were interviewee-guided based on the comments of research team. They were not sequential and just raised based on the progress of interview. The interview took 40–90 minutes. All the interviews were done by the first author. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. They continued until data saturation.33 The data saturation was confirmed when the codes were replica of the registered ones, and the process of data collection was completed through 17 deep interviews (12 faculty members and 5 students), which took 6 months.

Data analysis

To analyze the data, the contractual content analysis method was used. This method is used to explain an event, the viewpoints, or the review of subject-limited studies. In this mode, the items of data were extracted inductively and the researcher obtained a huge amount of data for perfect cognition.34 In this study, the data analysis was performed from the first interview based on the recommendations of Graneheim and Lundman.35 For this purpose, the recordings were transcribed. The entire interview was considered as a unit of analysis; then, the codes were extracted through the identification of the semantic units. Two other authors checked the sample of coded text and also the process of data analysis. Finally, 401 primary codes, 10 subclasses, and 3 classes were provided.

Rigor

To ensure the accuracy and trustworthiness of qualitative data, the Lincoln and Guba criteria and four constituents of credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability were used.26,27 In order to be satisfied with the long-term involvement of the researcher, a variety of sampling and data collection methods were used, and the results were finally checked with the help of participants,36 so they were given two interview scripts in order to clarify their perception about the given codes.

To increase the homogeneity of the study, the peer-checking method was used to such an extent that handwritten interviews were held confidential.

To provide transferability, all the study procedures (ie, introduction of participants, sampling, place and time of data collection, and data analysis) were recorded precisely. To increase the reliability, the researcher tried to not involve her assumptions into the data collection and analysis as much as possible. Data were collected and analyzed in 2018.

In terms of ethical consideration, the study was approved by ethical committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The study objectives and research methodology were explained to the subjects; they were also asked to sign the informed consent. They were also free to quit from the study at any stage and were assured about the confidentiality of their information including audio files.

Data were analyzed with MAXQDA 10. Also, the participants remained anonymous and were only identifiable by their phone numbers.

Results

The study participants included 17 faculty members and clinical students of medicine, nursing, and midwifery selected from Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Bushehr University of Medical Sciences. In data analysis, after the removal of the repeated codes, 401 primary codes were extracted, which were classified as the professionalism principles, professional responsibility, and professional evidence (Table 1).

| Table 1 Themes and categories that emerged from Interviews with participants |

Professionalism principles

Communication with the patient

Communication with the patient was an ethical commitment and participants found it important in moral reasoning. Having the communication skills and considering the differences in communicating with patients were efficient, so unfamiliarity with communication principles was a major obstacle. Also, the communication with the patient and participation of the patient in decision-making create empathy and sympathy between the patient and the treatment team, build trust in the patient, and provide an opportunity to explore his/her mental challenges. Regarding the importance of familiarity with communication skills, one of the participants stated:

We need to have strong counseling skills. Listen to them carefully and make a conclusion based on their own words in order to analyze the issue and give them important information [Participant No. 16].

The participants believed that such amount of skills is not enough and emphasized the importance of using different styles in making communication with patients. He added:

But in my opinion, many of us are not familiar with communication skills; although we are really in the community, dealing with patients is considerably different [Participant No. 2].

Participants emphasized paying attention to mental challenges of patients and their solutions; one in this regard said:

Speaking to the patient means that I talk every day to patients and their relatives about their mental issues in order to solve them as much as possible [Participant No. 6].

Understanding emotions and sympathy with the patient and his family facilitates communications and makes the therapist more committed to taking care of the patient.

It is very important to be able to understand the patient and have sympathy with him/her [Participant No. 2].

But those emotions are important. Actually, if you have sympathy with the patient, surely you have more commitment with your job [Participant No. 17].

Participation sayings suggest that effective communication with the patient is highlighted in people with different experiences.

Trust building

The participants found trust building affects decision-making.

Witnessing the physician’s efforts in treatment, talking to patient’s family, giving the patient complete information, ensuring the patient about the adequacy and competence of the treatment team, having sufficient knowledge and skills in decision-making, having no doubt in the diagnosis, and counseling other physicians for better management are the factors that affect building trust. Participants believed that such kind of trust creates a greater sense of responsibility in the therapist to better accept unintended errors. Having the communication skills and not leaving things unsaid can strengthen this trust. According to the participants:

We need to do something to build trust between the patient and his/her family, and the physician and the treatment team, since the lack of trust does not make good sense; blaming others does not make us popular. We have to do our best to make the patient satisfied with the treatment team and trust them, not matter if he is the physician, midwife, nurse, or physiotherapist, etc. [Participant No. 4].

A Physician spends 10 minutes to give sufficient information about the disease process, the patient’s health state, and prognosis to the patient’s family. Under such circumstances, I think no patient or his/her companions complain against the doctor; I really do not think so. I have always tried to build a sense of trust in the patient [Participant No. 6].

Trying to satisfy the patient

The participants noted that trying to satisfy patients is another professional principle in moral reasoning.

Participants believed that patients are eager to receive information about their illness from the treatment team and found it their efforts to treat the disease; in addition, such satisfaction makes the patient ready to use cheaper and available drugs. According to the participants, the patients’ companions pay attention to the treatment team efforts and their companionship, although alleviating the patient’s pain and discomfort is also an important factor in creating the satisfaction. In this regard, a participant said:

Just for the physician’ convenience, it is better to tell everything to patient; if the prognosis of the disease is bad, tell them, of course, I do not like to make him hopeless by informing about his bad health status. He and his family would like to be informed of everything [Participant No. 6].

Explaining the reason of choosing the best treatment method makes the patient satisfied:

I highlight the treatment method and tell the patient that the current method is good, it has been used for a long time, but nowadays, the latest drugs come to the market so do the high-end cars, all of us get going to the newest and latest cars but the older ones do their jobs well, too. In fact, we are prescribing that drug. Although the latest drugs come, I am satisfied with the older ones, too. It is OK [Participant No. 11]. If the patient feel that his treatment is taken into consideration and the therapist is patient to do his job, he will be happy with it [Participant No. 12].

Moralism

Observing ethics in moral reasoning was one of the issues that participants highlighted in dealing with patients. Participants stated that the things such as being honest with the patient, resistance against invalid orders of authorities, being tolerant in dealing with patients, observing moral standards in imposing medical expenses on the patient, being conscientious, observing the ethical standards acquired from the family, the impact of positive attitudes, and the integrity of mind and practice in observing the ethical principles are other examples of ethics in decision-making.

In this regard, a participant added:

I do not lie to the patient, if I cannot do the surgery, I do not tell it at the last moment. I cannot ditch them and leave them hanging. I tell them immediately to refer someone who can handle it [Participant No. 3].

If I (the physician) brought up in a family that was not indifferent to others; for example, the family that did not just focus on philanthropy and materialism, while spirituality, morality, and help others were also institutionalized in it, well, I understand my real position, which is the most important profession in medicine; and both patient and his/her companions trust in me; I think all of them back to that underlying teaching guiding me to act based on them [Participant No. 4].

I think the most important thing that we hardly try to be is honesty. This is a rule for me. As far as all my colleagues and friends know, I am highly honest in my job [Participant No. 3].

Professional responsibility

One of the levels derived from participants’ experiences is to observe the professionalism in moral reasoning associated with meanings like observing professional principle, preserving the professional position, responsibility, and patients’ dignity.

Responsibility to perform the duties

The participants believed that checking and ensuring the accuracy of measures taken for patients, disregarding the nonscientific requests of patients, undoing the practices that are not scientifically qualified, avoiding assignment of affairs to nonskilled people, and having enough scientific knowledge in making decision for patients are the examples of responsibility in health care practices. They also emphasized that the passion for work makes the patients pleasant to recovery, so that some measures such as detaching ventilator is difficult for them and makes them more responsible to do their best for patients’ recovery. According to the participants, observing the principles of honesty and truth, not following emotions, and making decisions in case of error possibility are of great importance and following these principles is an example of professional responsibility.

I always say that when I get back home from work, I know better than everyone that how I was today for the patients. I really tried to do what was morally correct because conscience does not tell lies; it is a criterion for myself [Participant No. 8].

I love my work very much; when I see the good results I feel very good. Unlike when I do not get a good result, I’m very upset, which makes me try to do a good job [Participant No. 6].

Compliance with professional principle

One of the manifestations of job commitment in moral reasoning in the current study was observance of professional rules in which participants emphasized expression of facts at the time of weakening of the patient’s rights, considering the legal consequences in dealing with nonscientific requests, and having sufficient knowledge and skills to make decisions.

I often try to understand the limits not to put myself in danger. For example, if the patient is an addict, I do not fulfill his needs just based on his request [Participant No. 7].

Maintaining the professional position

From the viewpoint of participants’ moral reasoning, if the therapists do not fulfill their duties with great responsibility, they may lose their position.

Paying attention to professional virtue, avoiding reputation damage from the viewpoint of colleagues and the health system, and doing practices in the best manner can maintain the professional position from the viewpoint of the participants. One of the participants said:

The trust that personnel have in the quality of my work is important. Such things, in any case, affect my decision and I can deal with my job easier [Participant No. 15].

Medicine is recognized as the sacred profession of the community. So, the keystrokes in my mind are important, however, some professions are sacred [Participant No. 15].

Patients’ dignity

The participants considered the respect to the dignity and altruism an important issue in professional principles for ethical decision-making. In this regard, having respectful behavior with patient, being honest, having a lot of respect for their wishes, and keeping their secrets are efficient.

In participants’ opinion, sometimes, telling the patients the truth about their malignant disease may disappoint him and make him to cease the treatment; under such circumstances, explaining the disease in a simple way has a good effect on life expectancy and boosts the morale in patients.

A participant said:

Paying attention to human dignity is very important to me. I think we are human beings and we have to respect humanitarian principles [Participant No. 8].

What always matters to me is that the person sitting in front of me is a human being. First of all, my words are not based on a stereotype; maybe my behavior reflects it; after all, everyone here knows what I’m doing. In fact, their financial status does not matter. I’m looking at him as a human being [Participant No. 6].

“It is important to me that all of us are human beings; in other words, humans are very important to me and they should be treated properly [reproductive health specialist with 23 years of experience].”

Professional evidence

Professional evidence is another class extracted from the participants’ experiences. According to one of the participants, getting help from the patient in making decisions as well as personal and others’ experiences and applying the professional knowledge are the evidences used in moral reasoning.

Getting help from the patient in decision-making

From the participants’ points of view, regarding the mental challenges of patients, talking to them about a right treatment method, revealing the realities of treatment, considering his socioeconomic and cultural status, and getting help from patient about revealing the reality to his accompanists are examples that can be helpful in reasoning and decision-making.

Sometimes when I get stuck in dilemma, I tell my patient I do not know what to do now. If you prefer to talk to other physicians, OK! Go on. Otherwise we do as we decided [Participant No. 2].

It is the patient’s right to make the final decision if there are several therapies for him. I tell him that there are some options; I can explain all the complications. If he answered, it will be logical to do it, if not, I ask his/her companions. Finally, if they all cannot decide, I will eventually decide [Participant No. 6].

I always do need analysis in order to know my patient to some extent; if I know him a little bit, I can decide better [Participant No. 7].

Self and others’ experiences

Consultation with experienced colleagues and using experiences, knowing their decision-making methods, benefitting from previous mistakes in managing new situations, and relying on counselors’ strategies are of ethical guidelines that lead to better decision-making. According to this, it promotes the ability and self-confidence in decision-making, along with a change in the type of decision-making over time.

I myself talk and consult with my experienced colleagues when I doubt my diagnosis on a case [Participant No. 4].

If I think there is something wrong with my diagnosis, I involve an experienced person. I do not decide alone. I always try to consult [Participant No. 3].

If I have no knowledge about a certain disease, I tell the patient, let me study on it and see what decision my colleagues and I can make in order to reach a consensus [Participant No. 2].

You’ve heard of a very prominent professor, and let him make a decision for you, because you know that his knowledge in this area is enough to protect you [Participant No. 2].

Professional knowledge

The participants found that choosing a right method for treatment based on the latest studies, applying the most updated sciences, not imposing the nonscientific costs, and learning the lessons from the mistakes are the professional principles; also, decision-making based on the scientific evidence is of ethical commitment in their job.

It’s a priority for me to decide based on what I’ve read or learned, and it is important to me to do a scientific work properly [Participant No. 12].

Discussion

The results of this study showed that professionalism manifests its role in the moral reasoning through professional principles, professional responsibility, and professional knowledge.

Participants in this study stated that communication with patient, trust building, trying to create satisfaction, and dignity of the patient are important ethical principles in professionalism in moral reasoning.

This relationship should be such that, in accordance with the four principles of medical ethics, the rights of the patient are not undermined; for example, the patient’s contribution in decision-making, the usefulness of the physician practices, the safety of decisions made for the patient, and the observance of justice in all things related to the patient should be preserved.28

Williams and Stickley believed that empathic interaction with patients, including a proper understanding of patients’ experiences, concerns, and viewpoints, has positive outcomes such as greater compatibility with the disease.29 It also plays a critical role in the physician’s clinical practice to perform the best care and build trust and satisfaction in the patient.30 Communicating effectively and empathy with the patient helps the physician to get information from him/her, and those who have more active strategies to accomplish are more successful in patients’ self-management and prognosis.31,32 On the contrary, this patient-centered approach is more effective in diagnosis, better prognosis, patient satisfaction, reduced medical costs, and compliance with the principle of considering patient’s benefit and preventing the damage to the patient, which is one of the most important ethical principles in moral reasoning.33–35 In contrast, poor communication with the patient leads to losing dependence and trust in the physician.34 Of course, patient characteristics, their health conditions, and communication skills are influential.

In fact, moral reasoning followed by ethical decision-making, in which the patient’s needs and care are taken into account, affects the quality of communication between the patient and the treatment team.9 Studies show that using effective educational methods, constructive feedback, and students’ interaction with patients lead to the development of communication skills and the improvement of medical outcomes, health, and patient satisfaction,36–38 and without such skills, doctors do not learn the professionalism and skills. The results of the study also indicated that communicating with the patient through building trust, creating satisfaction, and observing the professionalism are effective in moral reasoning.

Participants in this study also considered professional responsibility as an aspect of professionalism in moral reasoning. Responsibility, observance of professional rules, and preserving professional position and patient dignity are the themes effective in this regard. Since the respect for human dignity is fundamentally different from the other rights that God has granted to human and human is not deprived of it under any circumstances,39,40 telling the truth to the patient is essential to respect him/her and maintain his dignity, which leads to strengthening the sense of independence and empowerment in the patient and his involvement in decision-making.32

Getting information from a patient in a judgment-free environment and communicating with the patient are also a kind of respect for the patient. In the educational model, which is a suitable method to interview and communicate with the patient, it is also important to be patient and reliable in knowing the patient’s beliefs.32 Sadeghi and Ashktorab believe that poor communication with the patient leads to violating the patient’s rights.41 Therefore, the physicians and the treatment team are aware of patients’ rights and the principle of autonomy in the patient.42 In this study, the participants also considered the observance of professional rules to prevent legal consequences in the work. Of course, most people believed that using the past mistakes and consulting with experienced people can raise the awareness of the legal aspects of work. Özdemir et al also stated that 40% of doctors do not know the legal aspects of their work, and 63% of them have never read anything about patient rights.43,44 In a study to assess the physicians’ knowledge and attitudes toward legal issues in medicine, they emphasized the acquisition of legal information in clinical practices and considered it effective in making decisions.45 Awareness of ethical contexts in clinical practices results in the contribution of ethical aspects to the process of clinical decision-making and failing to be aware of that affects legal consequences for both the physicians and the students.46 Keeping the patients’ secrets was another item that the participants noted in professional responsibilities. The patient’s desire to know the truth is one of the most important factors in revealing his/her secrets.47 In all societies, it is important to observe keeping secrets and maintaining the patient’s privacy.48 Not respecting the patient’s privacy leads to dissatisfaction, the development of patient health problems, defects in the process of recovery, and increased complaints against the medical staff.48 Studies show that young patients and their families are more inclined to reveal the facts of the disease,40 while 53%–64% of patients with cancer do not receive enough information about their diagnosis or treatment.49 In a study conducted by Grassi et al, 45% of doctors believed that the patient should legally be in a state of illness, but only 25% revealed the facts to the patient; however, specialists are more interested in it compared with experienced physicians and general practitioners. And one-third of them did not tell the truth to the patient, while evidence suggests that expressing the facts and giving accurate and complete information to the patient affect the compliance of patients with the illness and their satisfaction.49 Training on time, place, and the way of revealing the patient’s secrets lead to the professional responsibilities in the treatment team. Developing the skills of secrecy and accountability in students can be achieved through teaching theoretical and practical subjects in the clinical field and the development of mental skills.50 Such skills can be trained in a variety of ways, such as lectures, but teachers can institutionalize it using some methods such as the reverse classroom action.38 The results of a qualitative study showed that the most successful programs in teaching decision-making skills are learning based on a problem in the real situation, which is helpful in implementing methods such as inverted classes (flip classroom).51 On the contrary, the teaching of ethics and the features of professionalism in medicine lead to the training of virtuous physicians, so that they have the ability to recognize difficult moral situations and find practical and ethical solutions.19

The results of the study aimed at influencing the course of medical ethics training on students’ ethical sensitivity showed that ethical observance in the medical profession is more affected by the profession and is not related to the nationality, gender, and age. This shows that teaching medical ethics in different countries has the same goals.52 This suggests that maintaining the patient’s respect and discipline in medical ethics is a concern.

Participants in this study considered the passing of time and the experience of others and professional knowledge as good guide to argue with patients. Today, global participation in the decision-making process is a fundamental necessity. Studies show that the participation of patients in decision-making on treatment is effective in recovery.35 Getting help from patients in decision-making can develop patient’s information, reduce conflicts regarding the decisions, and inform them about their right to choose the treatment and self-care practices, although the experience of the physician and the patient’s viewpoint affect this conclusion.53,54 Varcoe et al also emphasize the important role of knowledge, experience, risk taking, and problem-solving ability to solve ethical problems.55

Scientific findings also indicate that an increase in experience boosts the capacity for moral reasoning,56 because this cognitive ability evolves through the repetition of exposure and experience in trying to improve the patient.57 People who learn from experiences and mistakes make better decisions and actions and have higher social accountability.58

Practical commitment and deep satisfaction in experienced people make them more committed to fulfilling their duties without any monitoring system, so they act more ethically in gaining further skills.

The power of sharing increased the experience of others.52 In the current study, participants emphasized the importance of acquiring knowledge and making decisions based on the scientific principles. Murrell believes that adherence to professional principles, along with the knowledge and skills, reflects the ability of physician in decision-making.57 According to Ducas,59 using the patient’s clinical evidence and his scientific skills and abilities in clinical judgment, an experienced physician reflects his activities, which in turn develops professionalism in moral reasoning and transfers such capability to future physicians.52,60,61 While medicine, as a valuable profession, is effective when the physician pays deep attention to the patient as a human being, this profound understanding is accompanied by a sense of sympathy and sufficient knowledge.28 Insufficient knowledge of physicians in the estimation of prognosis and lack of sufficient knowledge about the legal aspects of the work lead to ineffective communication and care for patients.62 Therefore, the observance of ethical aspects aiming at serving the community and responding to the needs of society require the acquisition of extensive academic knowledge.63

Conclusion

Moral dilemmas are the most important medical ethics that happen frequently during the professional activities and sometimes make the treatment team up in the air. If there are not enough skills facing these events, immoral behaviors are inevitable.

Moral reasoning is one of the essential skills to provide complex medical services to patients, and inability in this area leads to inadequate care for the patient.

Being more familiar with the ethical concepts and applying the professional ethics based on the cultural trainings in each society can play a key role in developing and promoting the moral reasoning ability.

Professional principles, professional responsibility, and professional knowledge are important aspects of professionalism in moral reasoning. The training of these aspects affects students in their compliance with clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgments

This study is a part of thesis written by Dr Farahnaz Kamali supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The authors appreciate the faculty members and students for their participations.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Tsai TC, Harasym PH, Coderre S, McLaughlin K, Donnon T. Assessing ethical problem solving by reasoning rather than decision making. Med Educ. 2009;43(12):1188–1197. | ||

Vahedian Azimi A, Alhani F. Educational challenges in nursing ethical decision making. Med Ethics Hist Med. 2008;1:21–30. | ||

Keskin-Samancı N. A study on the link between moral judgment competences and critical thinking skills. Int J Environ Sci Educ. 2015;10(2):135–143. | ||

Paul R, Elder L. Critical thinking: ethical reasoning and fairminded thinking, Part I. J Dev Educ. 2009;33:36. | ||

Dehghani A, Dastpak M, Gharib A. Barriers to respect professional ethics standards in clinical care viewpoints of nurses. Iran J Med Educ. 2013;13:421–430. | ||

Cerit B, Dinç L. Ethical decision-making and professional behaviour among nurses: a correlational study. Nurs Ethics. 2013;20(2):200–212. | ||

Swisher LL, van Kessel G, Jones M, Beckstead J, Edwards I. Evaluating moral Reasoning outcomes in physical therapy ethics education: stage, schema, phase, and type. Phys Ther Rev. 2012;17(3):167–175. | ||

Ebrahimi H, Nikravesh M, Oskouie F, Ahmadi F. Stress: major reaction of nurses to the context of ethical decision making. Razi J Med Sci. 2007;14:7–15. | ||

Goethals S, Gastmans C, de Casterlé BD. Nurses’ ethical reasoning and behaviour: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(5):635–650. | ||

Kollemorten I, Strandberg C, Thomsen BM, et al. Ethical aspects of clinical decision-making. J Med Ethics. 1981;7(2):67–69. | ||

Brody H, Doukas D. Professionalism: a framework to guide medical education. Med Educ. 2014;48(10):980–987. | ||

Howe A. Professional development in undergraduate medical curricula--the key to the door of a new culture? Med Educ. 2002;36(4):353–359. | ||

Al-Eraky MM, Donkers J, Wajid G, Van Merrienboer JJ. Faculty development for learning and teaching of medical professionalism. Med Teach. 2015;37(Suppl 1):S40–S46. | ||

Madani M, Saeedi Tehrani S. Evaluation and comparison of conventional ethical decision-making models in medicine. Iranian J Med Ethics His Med. 2016;9:11–25. | ||

Han SS, Kim J, Kim YS, Ahn S. Validation of a Korean version of the moral sensitivity questionnaire. Nurs Ethics. 2010;17(1):99–105. | ||

Dierckx de Casterlé B, Izumi S, Godfrey NS, Denhaerynck K. Nurses’ responses to ethical dilemmas in nursing practice: meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63(6):540–549. | ||

Safaeian L, Alavi S, Abed A. The components of ethical decision making in Nahj al-Balagha. Iranian J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2013;6:30–41. | ||

Freeman SJ, Engels DW, Altekruse MK. Foundations for ethical standards and codes: the role of moral philosophy and theory in ethics. Counsel Val. 2004;48(3):163–173. | ||

Eckles RE, Meslin EM, Gaffney M, Helft PR. Medical ethics education: where are we? Where should we be going? A review. Acad Med. 2005;80(12):1143–1152. | ||

Prescott J, Becket G, Wilson SE. Moral development of first-year pharmacy students in the United Kingdom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(2):36. | ||

McLeod-Sordjan R. Evaluating moral reasoning in nursing education. Nurs Ethics. 2014;21(4):473–483. | ||

Glick SM. The teaching of medical ethics to medical students. J Med Ethics. 1994;20(4):239–243. | ||

Koohi A, Khaghanizade M, Ebadi A. The relationship between ethical reasoning and demographic characteristics of nurses. Iranian J Med Ethics Histor Med. 2016;9:26–36. | ||

Tsai TC, Harasym PH. A medical ethical reasoning model and its contributions to medical education. Med Educ. 2010;44(9):864–873. | ||

Omidi N, Asgari H, Omidi MR. The relationship between professional ethics and the efficiency of the nurses employed in Imam Hospital and Mostafa Khomeini Hospital in Ilam. Iranian J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2016;9:65–73. | ||

Anfara VA, Brown KM, Mangione TL. Qualitative analysis on stage: making the research process more public. Educ Res. 2002;31(7):28–38. | ||

Patton MQ. Qualitive Evaluation and Reaserch Methods. (2nd ed). Thousands oaks, CA, US: sage publication, Inc; 1990. | ||

Khadem Alhosseini Z, Khadem Alhosseini M, Mahmoudian F. Investigating the ethical and behavioral role of the physician in respect of medical instructions by the patient in the treatment process. Med Ethics J. 2009;3:91–101. | ||

Williams J, Stickley T. Empathy and nurse education. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(8):752–755. | ||

Symons AB, Swanson A, McGuigan D, Orrange S, Akl EA. A tool for self-assessment of communication skills and professionalism in residents. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9(1):1. | ||

Jha V, Bekker HL, Duffy SRG, Roberts TE. A systematic review of studies assessing and facilitating attitudes towards professionalism in medicine. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):822–829. | ||

Flickinger TE, Saha S, Roter D, et al. Clinician empathy is associated with differences in patient-clinician communication behaviors and higher medication self-efficacy in HIV care. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(2):220–226. | ||

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. | ||

Maatouk-Bürmann B, Ringel N, Spang J, et al. Improving patient-centered communication: results of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(1):117–124. | ||

Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse education today. 2004;24(2):105–12. | ||

Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):755–761. | ||

Branch WT. The road to professionalism: reflective practice and reflective learning. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(3):327–332. | ||

van Mook WN, van Luijk SJ, de Grave W, et al. Teaching and learning professional behavior in practice. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(5): e105–e111. | ||

Avizhgan M, Mirshahjafari E. Dignity in medicine: emphasis on dignity of end stage patients. Iran J Med Educ. 2012;11:1496–1510. | ||

Rosenberg AR, Wolfe J, Wiener L, Lyon M, Feudtner C. Ethics, emotions, and the skills of talking about progressing disease with terminally ill adolescents: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1216–1223. | ||

Sadeghi R, Ashktorab T. Ethical problems observed by nurse students: qualification approach. Med Ethics J. 2016;5:43–62. | ||

Ardeshir Larijani M, Zahedi F. The effect of ethical philosophy on ethical decision making in medicine. Iran J Diabet Metab. 2004;4:25–38. | ||

Yaghobian M, Kaheni S, Danesh M, Rezayi Abhari F. Association between awareness of patient rights and patient’s education, seeing Bill, and age: a cross-sectional study. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6(3):55. | ||

Özdemir MH, Ergönen AT, Sönmez E, Can IO, Salacin S. The approach taken by the physicians working at educational hospitals in Izmir towards patient rights. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(1):87–91. | ||

Parker M, Willmott L, White B, Williams G, Cartwright C. Medical education and law: withholding/withdrawing treatment from adults without capacity. Intern Med J. 2015;45(6):634–640. | ||

Manson HM. The development of the CoRE-Values framework as an aid to ethical decision-making. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):e258–e268. | ||

Asai A. Should physicians tell patients the truth? West J Med. 1995;163(1):36. | ||

Mohammadi M, Diani Tilaki M, Larijani B. Attitude of patients about privacy and confidentiality in selected hospitals in Tehran. Iranian J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2017;9:5–19. | ||

Grassi L, Giraldi T, Messina EG, Magnani K, Valle E, Cartei G. Physicians’ attitudes to and problems with truth-telling to cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8(1):40–45. | ||

Kuiper RA, Pesut DJ. Promoting cognitive and metacognitive reflective reasoning skills in nursing practice: self-regulated learning theory. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(4):381–391. | ||

Cummings CL. Teaching and assessing ethics in the newborn ICU. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40(4):261–269. | ||

Chiapponi C, Dimitriadis K, Özgül G, Siebeck RG, Siebeck M. Awareness of ethical issues in medical education: an interactive teach-the-teacher course. GMS J Med Educ. 2016;33(3):Doc45. | ||

Coylewright M, Branda M, Inselman JW, et al. Impact of sociodemographic patient characteristics on the efficacy of decision aids: a patient-level meta-analysis of 7 randomized trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(3):360–367. | ||

Salloch S, Ritter P, Wäscher S, Vollmann J, Schildmann J. Medical expertise and patient involvement: a multiperspective qualitative observation study of the patient’s role in oncological decision making. Oncologist. 2014;19(6):654–660. | ||

Varcoe C, Doane G, Pauly B, et al. Ethical practice in nursing: working the in-betweens. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(3):316–325. | ||

Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A, Kohan M, Fazael MA. Nurses and nursing student’s’ ethical reasoning in facing with dilemmas: a comparative study. Iranian J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2010;3:71–81. | ||

Murrell VS. The failure of medical education to develop moral reasoning in medical students. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:219–225. | ||

Guraya S, Guraya S, Almaramhy H. The legacy of teaching medical professionalism for promoting professional practice: a systematic review. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2016;9(2):809–817. | ||

Doukas DJ, McCullough LB, Wear S, Lehmann LS, Nixon LL, Carrese JA, et al. The challenge of promoting professionalism through medical ethics and humanities education. Academic Medicine. 2013;88(11):1624–9. | ||

Chalmers P, Dunngalvin A, Shorten G. Reflective ability and moral reasoning in final year medical students: a semi-qualitative cohort study. Med Teach. 2011;33(5):e281–e289. | ||

Carrion C, Soler M, Aymerich M. Professionalism evaluation in medical students. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;116:1880–1884. | ||

Visser M, Deliens L, Houttekier D. Physician-related barriers to communication and patient- and family-centred decision-making towards the end of life in intensive care: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2014;18(6):604. | ||

Yamani N, Changiz T, Adibi P. Professionalism and hidden curriculum in medical education. 1st ed. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. [Persian]. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.