Back to Journals » Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dentistry » Volume 13

Evaluation of Dental Program for Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Facilities

Authors Rao S, Shenoy R , Karat D, Poojary D, D'Souza V

Received 17 March 2021

Accepted for publication 20 May 2021

Published 29 June 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 275—281

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CCIDE.S311019

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Christopher E. Okunseri

Shushma Rao,1,2 Ramya Shenoy,2,3 Dolphin Karat,4 Dharnappa Poojary,2,5 Violet D’Souza6

1Department of Prosthodontics and Crown and Bridge, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore, Karnataka, India; 2Affiliated to Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India; 3Department of Public Health Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore, Karnataka, India; 4Department of Medicine, Fr.Muller Homoeopathic Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India; 5Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore, Karnataka, India; 6Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Correspondence: Ramya Shenoy

Department of Public Health Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore, Email [email protected]

Dharnappa Poojary

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Compared to the general population, older adults living in long-term care facilities have poorer oral health. Also, they seldom have access to dental care services. Given that, a dental health program was initiated by Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore (MCODSM), to deliver dental care to the residents of St. Antony Home (SAH), a long-term care facility in Mangalore, India. This study aimed to evaluate the dental program by investigating the views and recommendations toward the program through its stakeholders.

Methodology: The stakeholders were divided into three groups: Group 1, transport personnel; Group 2, coordinator and administrators of the program from both the sites; and Group 3, the residents of SAH who received dental care at the MCODSM. Data were collected through a structured questionnaire to measure satisfaction levels of the participants. Data analyses included calculating the frequencies required to describe the evaluation outcomes narrative.

Results: A total of 19 stakeholders participated in the study, of them 12 were SAH residents (Group 3). These Group 3 participants received various kinds of dental care. Almost all stakeholders were satisfied with the program and reported that the program was beneficial to the SAH residents. The stakeholders of the program were satisfied with transportation, the time allotted for the treatment, and the attitude of the dentists who delivered the program.

Conclusion: The dental program was successful in delivering the most needed dental care to SAH residents. It provided an opportunity to provide treatment to SAH residents, and the stakeholders were highly satisfied with the program. That said, there are opportunities to improve the program, especially in relation to transporting the SAH residents to the program site, having a single window to deliver the dental treatment, and acquiring more supporting staff. Future evaluations are warranted using well-designed evaluation procedures and larger samples.

Keywords: dental program, long-term care facility, older adults

Introduction

Most countries have a rising life expectancy and an aging population. This trend was initially seen in developed countries, but is now seen in all developing countries.1 Those who cannot live at home are being cared for in a range of residences based on their degree of dependency. Long-term care facilities, also known as nursing homes or old age homes, are alternative homes for the physically and mentally disabled elderly, including those who are financially deprived.2

Nursing home residents often have multimorbidities and thus take multiple medications, also known as polypharmacy. These residents often experience xerostomia.3 Xerostomia alters the oral microbiome, decreases self-cleaning and buffering actions in the oral cavity, and thus puts these individuals at a higher risk for oral diseases.4 Many older adults living in long-term care residencies experience cognitive decline.5 Due to multimorbidities, decreased manual dexterity, low self-efficacy, and cognitive decline, long-term care residents are less likely to perform optimum oral hygiene care. Thus, they may remain dependent on caregivers to perform their activities of daily living,6 including oral hygiene practices.

Studies have shown that caregivers may not perform oral hygiene practices for their care-dependent elderly.7 Also, these individuals have less access to dental care for various reasons and seldom receive the most necessary dental care.8 When they do receive dental care, it is limited to palliative dental care, meaning symptomatic treatment to relieve dental pain and discomfort. Often, they are referred to hospitals to receive dental care in emergency departments.9,10 Numerous studies have investigated the oral health status of older adults living in long-term care facilities in terms of the DMFT (Decayed, Missing or Filled Teeth) index. According to these studies, when compared to the general population, older adults living in long-term care facilities have a poor oral health status.11

Measuring the oral health status of older adults is complex because of their intricate illnesses and cognitive declines. To overcome these challenges, caregivers often serve as proxies in clinical care and research.12 Given that older adults are at a higher risk for poor oral health, the World Health Organization recommends that certain strategies be adopted to improve the oral health of the elderly.13 Even though there is a fast-growing elderly population, there are very limited dental programs available to serve them, especially for those living in long-term care facilities. There is also limited literature concerning the oral health of older adults living in long-term care facilities in India.

Given that, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore (MCODSM) initiated a dental program in 2016 to lessen the oral health-related burden of older adults living in St. Antony Home (SAH), a long-term care facility situated in the southwest coastal region of India. SAH was established in 1898 to take care of the poor, destitute, and orphans, rendering its services to the neglected section of society, irrespective of caste and creed, for over a century. Currently, it serves 400 residents. This study aimed to evaluate the dental program by investigating the views and recommendations toward the program through its stakeholders.

Objectives

- Administering the structured questionnaire to the stakeholders of the dental program, ie, two transport personnel, two coordinators (one from each site), three administrators (two from MCODSM and one from SAH), and the SAH residents.

- Gathering information from hospital records on dental treatment availed by the SAH residents.

Methodology

Description of the Dental Program at SAH

This dental program was implemented following a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between SAH and MCODSM on September 7, 2016. As per the MoU, one day a week was allotted for the dental program. On the allotted day, the residents were provided with transportation to the dental institution. Here their initial dental evaluation was done, and they were referred to different departments according to their treatment needs, such as scaling, extraction, prosthetic rehabilitation, and the treatment of mucosal lesions and candidiasis. This process was overseen by the coordinator from MCODSM. The residents were then dropped back to SAH. Those residents needing multiple visits were recalled the following week. Among the 400 residents, 75 have availed dental treatment through this program.

Study Design

An evaluation of the dental program was conducted at MCODSM and SAH with various types of stakeholders, including transportation staff (bus driver and an assistant), program coordinators and administrators, and the SAH residents who received dental care. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of MCODSM (Protocol no 0.17068, dated June 24, 2017) and all participants were required to provide informed consent before they participated in the study.

Study Participants

Study participants were key stakeholders of the program, along with three groups of participants. Group 1 participants were individuals involved in transporting SAH residents to and from MCODSM, and Group 2 participants were administrators and coordinators from SAH and MCODSM. Participants in Groups 1 and 2 had no specific eligibility criteria to take part in the evaluation, except for their willingness to do so. Group 3 participants were SAH residents who received any kind of dental care at MCODSM, age 60 years or older with no history or diagnosis of severe psychotic disorders or physical impairment.

Instrument

Using past literature, we developed a structured questionnaire required for evaluating our dental program through various types of stakeholders.14,15 It included questions about understanding the status of the dental program, the impact of the program on the residents, transportation-related issues, the time allotted for treatment, the attitude of the dentists, other challenges in conducting the program, and recommended changes to the program. The questionnaire was pretested with ten individuals directly involved in the program and adjusted as needed. Since most SAH residents speak the regional language Kannada, the questionnaire was translated to the standard procedure of back-and-forth translation.16 The translated version was reviewed by five potential participants of Group 3 who were excluded from the analyses.

Participants’ Recruitment and Data Collection

Potential participants were identified in person and were informed of the study. Those who agreed to participate were recruited into the study by obtaining written informed consent. All recruited participants were scheduled for an appointment for data collection in person either at MCODSM or SAH. Data collection included obtaining sociodemographic information and completing the above-mentioned questionnaire. All participants were assigned a unique participant identification code to maintain their privacy and confidentiality throughout the study, data analyses, and reporting processes.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL) using a statistical significance set at P < 0.05. Descriptive statistics were calculated using mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Given the small sample size and heterogeneity of the participants in the evaluation, only frequencies were calculated as required for the narrative description of the study findings.

Result

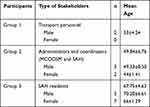

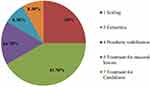

A total of 19 stakeholders participated in the evaluation. They include two transport personnel, two coordinators (one from each site), three administrators (two from MCODSM and one from SAH), and 12 SAH residents. The detailed demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The Group 3 participants were provided various forms of dental care. Of them, five (41.7%) underwent extraction, three (25%) received dental hygiene care (scaling), two underwent prosthetic rehabilitation, and two received treatment for oral mucosal conditions, as described in Figure 1.

|

Table 1 The General Characteristics of the Stakeholders |

|

Figure 1 Treatment provided to SAH residents. |

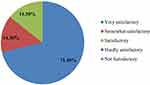

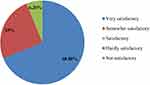

All the participants expressed satisfaction with the program, of whom 71% were very satisfied (Figure 2). Of the 84% of the participants who were satisfied with the transport arrangements, 53% were very satisfied (Figure 3). Most of the participants (68.8%), excluding the transport personnel, were very satisfied with the time allotted for the program (Figure 4). A vast majority (95%) of the participants were satisfied with the dentists’ interest in providing care to SAH residents, of whom one-third (30%) were very satisfied.

|

Figure 2 Stakeholders satisfaction level with the program. |

|

Figure 3 Stakeholders opinion on transport arrangement. |

|

Figure 4 Participants’ opinion on time allotted for program. |

When asked about the difficulties in running the program, three out of five Group 2 participants stated it was “somewhat difficult”. When asked whether they wanted any change in the dental program, all participants were fine with the program the way it was, except for the MCODSM coordinator. The MCODSM coordinator suggested having a single window for treatment and a few more support staff to run the dental program. Both coordinators of SAH and MCODSM agreed that the dental program had improved the resident participants’ oral health.

Discussion

This study describes the outcomes of an evaluation of an ongoing dental program for SAH residents conducted through various stakeholders. The opinion of stakeholders on any program is important as their response can help make a difference in the program and their support is needed to act on the results and recommendations of the program. These stakeholders can also be responsible for the implementation of any changes in the program.17 Our results indicate that the program was running smoothly with minimal challenges. A vast majority of the stakeholders expressed satisfaction with the transportation arrangement, the time allotted for treatment, as well as dentist’s attitudes about providing care to the SAH residents. Most importantly, all participants agreed that the program was beneficial to the SAH residents.

Excluding the transport personnel, most of our study participants (53%) were very satisfied with the transport arrangements. The transport arrangement appeared as an incentive for the SAH residents to utilize the dental care services. If the program did not include transportation, the SAH residents would have had to travel to receive dental care at their own expense. That would have hindered their interest and ability to utilize the most necessary care otherwise available to them. This has been observed in other studies,1 especially in low-income and socially isolated older individuals.7 Thus, providing transport was an excellent addition to the success of the program. Also, the time allotted for treatment was another positive element in running a dental care program smoothly. A reasonable length of designated time allotted for the treatment can help the patients, care providers, program administrators, and transport personnel, which is essential for the program’s success. Except for the transport personnel, all other participants were satisfied with the time allotted for the treatment. Although the satisfaction of the transport personnel is crucial, the factors that negatively affected their satisfaction levels were not assessed in this investigation.

All participants were satisfied with the dentists’ attitudes in providing care to the SAH residents. In our program, each SAH resident had their own dentist to prevent the overburdening of any one dentist. This was arranged so that the dentists would pay enough attention to their patients from SAH. Thus, the high dentist–patient ratio may have contributed to the higher satisfaction levels, which has been observed earlier.18

The following limitations should be considered while interpreting our study results. This investigation was a part of the program evaluation process, with participants being the key stakeholders of the program. Thus, the outcomes observed in this study do not reflect the impact of the program on patients alone. Also, since a very small number of SAH residents participated in the study, we are unable to perform inferential statistical analyses. Also, we collected data only through structured questionnaires that limited our ability to explore the stakeholders’ perceptions of the program beyond the questionnaire used in the study.

Conclusion

The dental program was successful in delivering the most needed dental care to SAH residents. It provided an opportunity to offer treatment to SAH residents, and the stakeholders were highly satisfied with the program. However, there are opportunities to improve the program, especially in relation to the transportation of the SAH residents to the program site, having a single window for the delivery of dental treatment, and acquiring more support staff. Future evaluations are warranted using well-designed evaluation procedures and larger samples.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee with the IEC number: 17068. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the stakeholders of the dental program conducted at the old age home for taking the time to participate in our study.

Funding

There was no funding for this study by any organization.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Nadig RR, Usha G, Kumar V, Rao R, Bugalia A. Geriatric restorative care - the need, the demand and the challenges. J Conserv Dent. 2011;14(3):208–214. doi:10.4103/0972-0707.85788

2. Agrawal R, Gautam NR, Kumar PM, Kadhiresan R, Saxena V, Jain S. Assessment of dental caries and periodontal disease status among elderly residing in old age homes of Madhya Pradesh. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7(8):57–64.

3. Putten G-J, Brand HS, Schols MGA, Baat C. The diagnostic suitability of a xerostomia questionnaire and the association between xerostomia, hyposalivation and medication use in a group of nursing home residents. Clin Oral Invest. 2011;15:185–192. doi:10.1007/s00784-010-0382-1

4. Mardian A, Darwita RR, Adiatman M. Factors contributing to oral health service use by the elderly in Payakumbuh City, West Sumatra. J Intl Dent Med Res. 2019;12(3):1123–1130.

5. Maseda A, Balo A, Lorenzo-López L, Lodeiro–Fernandez L, Rodríguez–Villamil JL, Millán–Calenti JC. Cognitive and affective assessment in day care versus institutionalized elderly patients: a 1-year longitudinal study. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:887–894. doi:10.2147/CIA.S63084

6. Chen S, Zheng J, Chen C, et al. Unmet needs of activities of daily living among a community-based sample of disabled elderly people in eastern china: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:160. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0856-6

7. Chen X, D’Souza V, Comnick CL, et al. How accurate is the assessment of certified nursing assistants on resident’s oral self-care function in three North Carolina assisted-living facilities? Spec Care Dentist. 2020;40(6):580–588. doi:10.1111/scd.12521

8. Omstien KA, DeCherrie L, Gluzman R, et al. Significant unmet oral health needs among the homebound elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):151–157. doi:10.1111/jgs.13181

9. Razak. PA, Richard KMJ, Thankachan RP, Hafiz KA, Nandakumar K, Sameer KM. Geriatric oral health; a review article. J Int Oral Health. 2014;6(6):110–116.

10. Scannapieco FA, Amin S, Salme M, Tezal M. Factors associated with utilization of dental services in a long-term care facility: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Spec Care Dentist. 2017;37(2):78–84.

11. Gaião LR, Almeida MEL, Filho JGB, Leggat P, Heukelbach J. Poor dental status and oral hygiene practices in institutionalized older people in Northeast Brazil. Int J Dent. 2009;2009:846081.

12. Gaszynska E, Szatko F, Godala M, Gaszynski T. Oral health status, dental treatment needs and barriers to dental care of elderly care home residents in Lodz, Poland. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1637–1644. doi:10.2147/CIA.S69790

13. Peterson PE, Yamamoto T. Improving the oral Health of Older people: the approach of the WHO Global Oral health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:81–92. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00219.x

14. Gagliardi DJ, Slade GD, Sander AE. Impact of dental care on oral health related quality of life and treatment goals among elderly adults. Aust Dent J. 2008;53(1):26–33. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.00005.x

15. Hirsch SH, Oakes AM, Schweitzer S, Atchison KA, Lubben JE, DeJong F. Enrolling community physicians and their patients in a study of prevention in the elderly. Public Health Rep. 1992;107(2):142–149.

16. Stewart JF, Spencer AJ Dental satisfaction survey 2002. AIHW Catalogue Number DEN. 141. Adelaide: AIHW Dental Statistics and Research Unit; 2005.

17. U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and prevention, Office of the director. Office of strategy and innovation. Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: a self- study guide. Atlanta, GA: Centers for disease control and prevention; October 13–17, 2011. Availabe from: https://www.cdc.gov/eval/guide/CDCEvalManual.pdf.

18. Lee W, Kim S-J, Albert JM, Nelson S. Contributing factors predicting dental care utilization among older adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(2):150–158. doi:10.14219/jada.2013.22

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.