Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Evaluation of a Career Resiliency Intervention for Special Education Teachers in China: Effects of Healthy Teachers Program

Authors Tian J , Zhou Y , Yu S

Received 4 December 2022

Accepted for publication 7 April 2023

Published 24 April 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1425—1437

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S400175

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Jinlai Tian,1 Yun Zhou,1,2 Shenggang Yu1

1School of Educational Science, Beihua University, Jilin City, People’s Republic of China; 2Jilin Agricultural Science and Technology University, Jilin City, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Shenggang Yu, School of Educational Science, Beihua University, Jilin Street 15, Jilin City, Jilin Province, 132013, People’s Republic of China, Tel/Fax +86-432-64602516, Email [email protected]

Background/Objective: This mixed-methods research aimed to examine the impact of the Healthy Teachers Program (HTP) on special education teacher career resilience.

Methods: Forty special education teachers recruited from Jilin, China, were randomly assigned to the intervention group (n =20) and the control (n =20) group. Data were collected using self-report questionnaires. The intervention group was taught eight program lessons by a school psychology teacher, which covered topics related to understanding career resilience, supporting self-awareness, changing career goals, and establishing interpersonal relationships. The researchers statistically analyzed the data collected at three-time points with repeated-measures analysis of variance and also conducted the focus group method to collect qualitative data for the social validity of HTP.

Results: The HTP positively influences the career resilience of special education teachers and has a high degree of social validity in the social significance of the goals and the social importance of the effects but an insufficient degree in the social appropriateness of the procedures. The findings of this study indicate the feasibility and applicability of the HTP to enhance the career resilience of teachers and its limitations in Chinese special school settings.

Conclusion: The health teachers program can effectively improve the career resilience of special education teachers and has a high degree of social validity.

Keywords: career resilience, intervention program, Chinese special education school teachers, social validity

Introduction

Previous research has indicated that Chinese special education teachers are vulnerable to mental health issues like depression, anxiety, and job burnout.1–3 Special education teachers were at a higher risk for mental health issues than the national norm.4 Compared with ordinary teachers, special education teachers who serve special children with physical and mental disabilities are more likely to suffer from greater pressure and burnout.5,6 As a result, it is hard for them to obtain a sense of career achievement and satisfaction from students, and it is also easy to overconsume emotional resources excessively.7–9

Several international programs exist to improve special education teachers’ mental health. Based on Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) and mindfulness training (MT), these programs are efficacious in preventing mental health problems among teachers in special education schools.10–13 However, it is difficult to systematically implement such programs within the school system because of the stigmatization of mental health problems in mainland China.14 In addition, due to the lack of supportive resources and policies and the heavy workload of teachers, few teachers can attend the whole process of mental health intervention programs.

London defined career resilience (CR) as person’s resistance to career disruption in a less than optimal environment “(p. 621).15 It emphasizes that individuals can also be positive when dealing with work difficulties, overcoming difficulties, and going out of adversity.16 CR is negatively associated with individuals’ mental health issues, and it is helpful to individuals who release work pressure and adapt to the working environment flexibly.17–19 Researchers regarded career resilience as a changeable, extensible, expandable psychological ability or advantage that can be cultivated or developed.20,21 They mainly use career counseling methods such as Career Stories,22 Career Construction Interview,23,24 Active Listening,25 the cognitive reappraisal of stress situations26,27 and other psychological and behavioral strategies based on positive psychology28 to improve career resilience. However, CR is a complex phenomenon involving individual characteristics and context interaction.29 These interventions focus on individuals and do not provide specific information about the interaction between individuals, families, and communities.30

The Career Resilience Framework (CRF) is a belief system for career development practitioners. In the context of CRF, they can help clients with career development obstacles by focusing on four main themes: (a) theme acceptance, (b) support for self-awareness, (c) conversion, and (d) connection.31 Theme acceptance denotes actively promoting resiliency theory throughout the organization by establishing policy and staff professional development strategies around the resiliency theme. Through these policies and professional development opportunities, employees can better deal with stress and any career-inherent change processes. Support for self-awareness refers to selecting or modifying career counseling processes or tools that improve the clients’ deep inner understanding of their core “values and interests”. Values and interests are fundamental components that must be considered when seeking to cultivate resilience. Conversion denotes helping clients identify and overcome barriers to convert their dreams into career realities—action planning through intrinsic motivation. Achieving this goal requires enhancing individuals’ intrinsic motivation, which encourages the development of action plans that enable them to overcome obstacles that may hinder their career goals. Connectedness refers to fostering a sense of community within a work environment and encouraging meaningful interactions among individuals.32 Through this connection, clients can better cope with daily sources of stress related to employment conditions, are more likely to develop strong problem-solving skills and grow professionally.31

The CRF can guide career development practitioners to select career counseling models and intervention methods and create environments in which clients can be truly motivated, build relationships, explore work possibilities, make decisions, set goals, and create action plans.31 Because of the complex working environment and working requirements that special education teachers often face, CRF may be particularly useful in studying the career development of special education teachers.33 Although many career development centers have successfully applied some themes of the CRF model, there needs to be empirical research to systematically explore the application of CRF in the special education teacher population.

Guided by the CRF and the actual working environment of Chinese school settings, the researchers promoted Healthy Teachers Program (HTP) to improve the career resilience of special education teachers. The researchers first translated the relevant materials into Chinese to better understand the four themes of CRF. Then, the researchers integrated the CRF with the specific content of previous intervention studies,34 flexibly adjusted and implemented the intervention plan based on the working environment of Chinese special teachers, and prepared the intervention content of HTP. For example, due to the frequent raids by relevant government departments on school safety, teaching, catering, and other work, some school leaders or teachers must participate in the entire process. As a result, HTP courses need to be adjusted or delayed. The program aims to improve special education teachers’ career resilience, self-consciousness, and interpersonal communication ability. Moreover, encourage them to have a strong awareness of their career goal, obtain more social support, and establish more harmonious interpersonal relationships.

The researchers used the HTP’s courses on career resilience (see Table 1) and intended to examine the impact of the HTP on special education teacher resilience in this study. We adopted a total of eight sessions as the intervention program. Each section was approximately 45 minutes long and was taught once per week. Researchers hypothesized that special education teachers who completed HTP would show (1) increased career resilience and its maintenance effect, (2) a high degree of the social validity of HTP.

|

Table 1 Career Resilience Lessons of HTP for Special Education Teachers |

Methods

A pretest, posttest, and follow-up test randomized control group design was used to determine whether completing the HTP would increase special education teachers’ career resilience and whether the effects would last over time. Researchers collected the three-time test data in November 2020, January 2021, and March 2021. In addition, one week after finishing the intervention, focus group interviews were conducted to collect the experience and feelings of teachers from the intervention group to obtain qualitative data on the social validity of HTP.

Statements of Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beihua University (No: 20200928) on September 28th, 2020. All study procedures involving human participants followed the ethical standards of institutions and the national research committee, the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, and its subsequent amendments or similar ethical standards. In addition, all participants in the study provided written informed consent before participating. All the participants were given a capital letter (eg, A, B, C, etc.) during the interview, and their confidential data will be published using the letter to protect their identity.

Participants

The participants were 46 special education teachers (7 males, 39 females) aged 26–55 years from special education schools in Jilin Province, China. They had previously participated in an extensive sample survey on the career resilience of special education teachers.

However, six teachers withdrew from the study due to work or family changes (such as business trips, sick leave, and the need to pick up their children from school in advance).

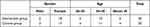

After excluding these incomplete data from analyses, a total of 40 teachers (5 males, 35 females) were included as participants, of whom 20 were randomly allocated to the intervention group (2 males, 18 females) and 20 to the control (waitlist) group (3 males,17 females). All teachers had complete data at three time points (see Table 2).

|

Table 2 Distribution of Basic Demographic Variables in Intervention and Control Group |

Measures

Career Resilience Scale (CRS)

The Career resilience scale (CRS), a 21-item scale developed by Chinese researchers, comprises six subscales that relate to different aspects of career resilience: (1) career initiative- exploring the development trend of the field and seeking better task assignments in work, (2) career vision- A clear career goal, clear direction, and clear understanding of what skills you have and how much value you can bring to the company, (3) learning ability- the ability to continuously learn new knowledge and professional skills by participating in professional meetings, reading books, etc., (4) achievement motivation- undertaking challenging work, (5) psychological resilience- controlling emotions, facing difficulties and not being easily defeated by setbacks, and (6) flexibility- welcoming changes in work or organization and being willing to work with a wide range of people.35,36 Teachers rate each item on a Likert 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The total score of the CRS represents the “career resilience” variable. The higher the total score of CRS, the better the individual’s career resilience. In this study, the CRS scale displayed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.80, 0.90, and 0.89 at the pretest, the post-test, and the short-term follow-up test, respectively).

Qualitative Measures of Teacher’s Focus Groups

Social validity studies analyze the social relevance of public health intervention goals, the appropriateness of their strategies, and the social significance of their impact, as perceived by the target audience, including the participants and the facilitators of the intervention.35 One quality indicator of intervention research is the extent to which the intervention has a high degree of social validity or practicality.37 In 1978, Wolf proposed a three-part framework for validating the social importance of interventions. In the framework, Wolf posited that intervention goals must be what society wants; procedures must be considered acceptable and feasible, and consumers should be satisfied with the intended and unintended effects.38 Qualitative designs are well-suited for examining social validity as they are based on ascertaining consumers’ perceptions in authentic contexts and also help researchers uncover unanticipated findings or further exploration.37,39

In this study, the researchers drew on Wolf’s framework for social validity. They used qualitative data to ascertain intervention group teachers’ perceptions and experience of attending the program to obtain the social validity of the HTP. Based on previous research on social validity,37,40 we designed the content of focus group interviews. The questions of which are listed in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Teacher Focus Group Interview Content |

Procedures

Intervention Procedures

After obtaining ethical approval from the ethics committee of the researchers’ university, the researchers contacted principals from five special education schools and explained the program. Then, the researchers invited these schools to participate in the study and received replies from the principals. Ultimately, all special education schools took part in the study. Researchers explained the purpose of the HTP to the research assistants and asked them to assist special education teachers in completing the tasks in the whole process of HTP. After the participants understand the purpose of the study and respond to their informed consent, researchers implement HTP formally.

In addition, the researchers adapted the materials of CRF to improve their applicability to Chinese culture and special education schools.

Career-resilient characters denote some psychological traits, including coping with problems and changes, social skills, interest in novelty, optimism about the future, and willingness to help others cope with risks and facilitate career development.41 The researchers incorporated these psychological traits into the intervention program to help teachers understand the concept of career resilience. To provide HTP content to special education teachers, the research implementers should encourage them to share their professional development experiences. The second author (a school psychology teacher) and two research assistants completed all courses during the weekly teacher’s group activity time (the sixth and seventh classes). Two research assistants were both graduate students of mental health education. The lessons covered eight units from the Healthy Teachers Program Achieve Career resilience lessons for special education teachers.

Data Collection Procedures

Owing to the school’s schedule, we administered the pretest questionnaire to the intervention and control groups in November 2020, one week before the program began (Table 3; Time 1). One week after the program ended in December 2020, all special education teachers participating in this study completed the post-test questionnaire (Table 3; Time 2). Finally, two months after the end of this program, in March 2021, they completed the short-term follow-up questionnaire task (Table 3; Time 3).

To obtain the social validity of HTP, most teachers (3 males, 9 females) in the intervention group accepted the invitation and agreed to participate in a one-hour focus group. Due to the teachers’ daily schedule inconsistency, focus groups were conducted with teachers in small groups (three focus groups; four teachers per group) to obtain information about their opinions about the HTP. All discussion of focus groups was recorded and transcribed into electronic text.

Data Analysis

Researchers carried out all quantitative data analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0. First, the researchers conducted preliminary analyses to ensure the groups were homogeneous at the pretest. The standard of homogeneity was that there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding gender, age, and career resilience. Next, repeated measure ANOVA was used to compare changes in the two groups’ career resilience at three-time points.

Researchers evaluated the social effectiveness of HTP by analyzing the experience and beliefs of special education teachers, following the six steps recommended by Braun and Clark for qualitative analysis:

- Read and become familiarized with the data;

- Generate initial codes in a systematic method;

- Identify themes based on available codes;

- Review codes and themes for accurate data representation;

- Define and name themes;

- Select vivid examples to illustrate the findings.42

Two research assistants transcribed verbal data into a written format and conducted a thematic analysis. Any information about the participant’s identity, such as their name and location, was deleted to ensure respondents’ privacy and the coding team members’ objectivity.

Results

Preliminary Results

A chi-square analysis revealed no significant differences in gender distribution between groups, χ2 (1, n=40) = 0.229, p=0.633, and there were no significant differences in age distribution between groups, χ2 (1, n=40) = 0.159, p=0.924. Furthermore, the t-test for analyzing group differences in the pretest indicated there were significant differences between the two groups in all but one subscale of CRS (career initiative: t (38) =0.952, p =0.347; career vision: t (38) =0.670, p =0.507; learning ability: t (38) =0.269, p =0.790; achievement motivation: t (38) =1.250, p =0.219; psychological resilience: t (38) =1.288, p =0.125; flexibility: t (38) =−3.953, p =0.0347; career resilience: t (38) =0.511, p =0.612). These results showed that the intervention and control groups were homogeneous in CRS in the pretest.

Next, the researchers tested whether the sample met the assumptions for repeated measure ANOVA and found that the findings met the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of the variance. Thus, researchers performed all subsequent analyses requiring a repeated measure ANOVA.

Intervention Effects

The Increased Career Resilience and Its Maintenance Effect

Table 4 presents the means, standard deviations, and significance testing for the intervention and control groups across time. In addition, a repeated measures ANOVA was carried out to examine the pretest, post-test with short-term follow-test changes in the performance of both groups on all dependent measures.

|

Table 4 Means, Standard Deviations, and Significance Tests for the Intervention and Control Groups Across Time |

This analysis confirmed that there were significant differences in all but one subscale score of CRS between the intervention group and the control group (career initiative: F (1,38) =2.738, p =0.069; career vision: F (1,38) =10.341, p =0.003; learning ability: F (1,38) =5.329, p =0.027; achievement motivation: F (1,38) =18.102, p <0.001; psychological resilience: F (1,38) =21.112, p <0.001; flexibility: F (1,38) =11.338, p<0.001; career resilience: F (1,38) =14.721, p <0.001). However, these results showed that in terms of career vision, learning ability, achievement motivation, psychological resilience, flexibility, and career resilience, the intervention group scored significantly higher than the control group.

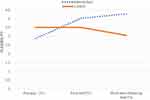

The results of repeated measures ANOVA showed that the main effect of test time on flexibility was significant, F (2,76) = 10.014, p < 0.01. The post hoc test showed that the flexibility of T1 was significantly lower than those of T2 (mean diff: 0.575, p=0.001) and T3 (mean diff: 0.475, p=0.005), but the difference between the two post-tests was not significant. The result showed that the intervention could improve the flexibility of the participants, and this change can be maintained until about two months after the intervention.

The interaction effect between test time and groups was significant, F (2,76) =23.114, p < 0.001. A simple effect analysis was further conducted, and the results showed that the flexibility of the intervention group on T2 (t=−6.296, p < 0.001) and T3 (t=−8.342, p < 0.001) were significantly higher than T1, and the flexibility scores between T2 and T3 were not significant. The flexibility of the control group was similar at the three-time points. Although the flexibility of the control group scored significantly higher on T1 than the intervention group (t=−3.947, p< 0.001), the flexibility of the intervention group scored higher on T2 (t=−2.686, p=0.008) and T3 (t=−6.323, p < 0.001) than the control group, as shown in Figure 1. These results showed that the improvement of flexibility in the intervention group mainly caused positive changes in flexibility.

|

Figure 1 The change of flexibility across time. |

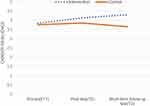

The results of repeated measures ANOVA showed that the main effect of test time on career resilience was insignificant. The interaction effect between test time and groups was significant, F (2,76) =3.440, p =0.037. Simple effect analysis showed that the intervention group scored significantly higher on the total score of career resilience in T3 than T1, t(38)=−2.884, p=0.006, and there was no significant difference between the career resilience score in T2 and T3. There was no significant difference in the total score of career resilience in the control group at the three-time points. The average total score of career resilience in T3 of the intervention group was significantly higher than that of the control group (t=−4.212, p< 0.0005), as shown in Figure 2. The results indicated that HTP could significantly improve the career resilience of the intervention group, and this maintenance effect can last until two months after the intervention.

|

Figure 2 The change of career resilience across time. |

The Social Validity of HTP

A summary of qualitative results regarding the social validity of HTP was displayed in Table 5, including themes about the social significance of the goals, the social appropriateness of the procedures, and the social importance of the effects.

|

Table 5 Summary of Qualitative Results About the Social Validity of HTP |

The Social Significance of the Goals

Most teachers expressed their high acceptance and satisfaction with HTP. They believed that the program had broadened their horizons and increased their understanding of and ability to cope with problems in their career development. “The objectives and contents of the program are clear and professional”. (Teacher F). “I was lucky to insist on participating in this program. The content was exciting and meaningful, so there was a high attendance rate. If there is such an opportunity the next time, my other colleagues also want to participate” (Teacher H). “I heard about the concept of career resilience for the first time through a program. It is of great importance for our special education teachers to cultivate the ability of career resilience”. (Teacher D). “The curriculum design is very reasonable. The problems teachers encountered in the examples are my problems in my daily work”. (Teacher A). “This is the first time I have participated in a program related to career confusion, and I think it is very beneficial for me”. (Teacher K). “It is necessary to deal with some related issues in the early stage of career development in the future, such as career vision, work pressure, and interpersonal relationship between colleagues”. (Teacher E).

The Social Appropriateness of the Procedures

Most teachers expressed their high acceptance and satisfaction with the procedure of HTP. They believed that HTP is a feasible and well-designed program that can be implemented in China’s special education schools. “This is a structured program. Every theme and activity are related, which I like very much”. (Teacher F). Teacher H said:

Unlike ordinary teachers, as special education teachers, we have to face students with various disabilities every day, and sometimes we cannot communicate with students or appropriately guide students. Therefore, We need to participate in more professional programs like HTP.

“I feel that I can completely relax in the relaxing setting and methods in HTP and establish a relationship of mutual trust and support with other unfamiliar colleagues”. (Teacher H). “My greatest gain is the learning process to support the development of self-consciousness, in which we can re-recognize ourselves and understand our potential in the interaction process”. (Teacher E). “In the process of label tearing, I can truly feel the negative emotions in my work, explore my own internal need, and re-establish my personal, professional attitude”. (Teacher A).

In addition, teachers mentioned some issues that affect the procedures or implementations, such as the time conflict, the complexities of program implementation, and other factors that restrict the program’s effectiveness. For example, “the eight-week long timeline (one lesson per week) or the schedule posed some challenges”. (Teacher H). “Teachers usually participate in the program after finishing class, so we had to manage the time to address overlapping school activities”. (Teacher B). “There are too many tasks to do, and I am sorry for always being late”. (Teacher N). “Because of our heavy work task and limited time, if the school fails to provide support, it may be rare to participate in the future. Whether some activities in this program can be carried out online?” (Teacher M). “The program duration is too short, which is not conducive to teacher’s understanding and experience. Can HTP add more class hours in the future?” (Teacher D).

The Social Importance of the Effects

Teachers provided positive feedback about the effects of HTP, perceiving it to be a valuable and effective program that can help teachers understand and cope with difficulties encountered in their professional development. “By building a mutual aid platform in HTP, we can discuss with each other when encountering difficulties, which has strengthened my confidence and social support in daily work”. (Teacher G). “We can get more strength and new guidance from the program”. (Teacher I). “My experience with HTP was very positive, which helped me cope with stress and negative emotion”. (Teacher B). “Teachers perceived changes in their work, such as improving their skills for connecting with the students, colleagues, and leaders”. (Teacher J). “The program was a decisive experience for me in my life. Because it was the first time unfamiliar colleagues put forward some objective suggestions face to face, I feel warm from the bottom of my heart so that my relationship in the school environment has been significantly improved”. (Teacher H). “I found my problems by learning interpersonal communication theory in HTP. The program helped people to learn how to establish good interpersonal relationships”. (Teacher F).

Some teachers reported future applications of HTP. For example, there were statements such as “The program should be implemented for all teachers at their start of career development” (Teacher H) and “I would like to learn more about career resilience in the future”. (Teacher K). “The experience of participating in HTP has helped me to establish a good friendship with my leader and colleagues. I hope this course will continue”. (Teacher B). Through learning in HTP, I recognized that I only cultivated my children’s ability and ignored their resilience at work or in daily life”. (Teacher L). “The emotional regulation strategies in HTP made me understand that it is normal to generate emotions in teaching, which is not a problem. What is important is my opinion and evaluation of my teaching and how I should properly adjust my emotions”. (Teacher F).

Discussion

This study evaluated the effect of an intervention program designed based on Rickwood’s career resilience framework on improving the career resilience of special education teachers. The intervention results showed that: compared with the control group, the career resilience of special education teachers participating in the HTP was significantly improved, and the intervention effect of the two indicators of flexibility and total score of career resilience could be maintained for two months after the end of the intervention. In addition, HTP has a high degree of social validity.

The Increased Career Resilience and Its Maintenance Effect

The researchers found that HTP can significantly improve the career resilience of teachers in special education schools, and its maintenance effect, including the total score of CRS and flexibility, can last for two months at least. This finding is not surprising. Although the intervention strategies adopted in this study are slightly different, this intervention plan also involves several essential characteristics of career resilience like other similar studies:43–45 (a) ability to cope with problems and changes, (b) social skills, (c) interest in new things, (d) optimism about the future, and (e) willingness to help others.46

Improving flexibility and social skills can be enhanced through internal and external resources and continuous reflection related to participation and personal practice. It can be considered one of the most effective strategies to prevent changes in work life from hindering career development.46,47 The intervention content of this study fully mobilized internal (individual motivation, desire, growth background, and experience) and external resources (school environment, interpersonal support). It guided teachers to reflect on the whole process continuously. Therefore, the intervention group had more significant changes in the dimension of flexibility. In addition, we found significant differences in the flexibility dimension between the two groups in the pretest. The reason may be that we did not control demographic variables such as school and major when randomly assigning subjects. To ensure a sufficient sample size for the two groups, we did not consider the inter-group difference in flexibility in the pre-test”.

We found that the impact of HTP on career initiatives was insignificant. The career initiative subscale is to explore the development trend of the field and seek better task assignments in work. Compared with Western countries, China’s inclusive education is just beginning. So far, the mainstream and special education schools are still in a state of separation. In addition, the probability of most special children continuing their education is very low, and their future development is also very rigid. Therefore, teachers’ daily work schedules and tasks in special education schools are similar, full of challenges and difficulties, and relatively dull. They have feedback on content involving “professional initiative”, but the effect is insignificant. In addition, due to the inability to change the actual issues related to career initiative (heavy workload, many problems with exceptional children, heavy inspection tasks), our HTP plan is more inclined to improve teachers’ cognition and interpersonal relationships. This is also one of the reasons why HTP has no significant impact on career initiatives.

The Social Validity of HTP

The researchers drew on Wolf’s framework for social validity in this study. We used qualitative methods to ascertain 12 special education school teacher’s perceptions of the social validity of HTP who came from the intervention group. Based on the sub-components of social validity in Wolf’s framework,37 special education teachers perceived the goals and outcomes of HTP to have a high degree of social validity. Furthermore, despite the social validity of the procedures having some problems, all teachers expressed a strong desire to continue participating in the program. There may be three reasons. First, teachers believe participating in HTP is more beneficial to them. Most teachers reported that they were more active in their work, had more precise goals, and could deal with work and interpersonal problems more flexibly. Second, teachers believe that the difficulties in the procedure they face are temporary and can be solved in the future, but it may take time. Third, the principals of several special education schools involved in this study attach great importance to teachers’ physical and mental health and encourage teachers to participate in similar mental health promotion plans.

Limitation

This exploratory study has several advantages, including a high participation rate, a clear theoretical framework, and a high degree of social validity. However, this study still has several limitations. Firstly, the assessment tool of this study is relatively simple, and only the Career resilience scale (CRS) is selected to quantitatively assess the changes in the level of professional resilience of special education teachers, lacking more detailed qualitative assessment data support such as later observation or interview. Secondly, all the evaluation data are self-reported, and the results may be influenced by social expectations, with deviation. Thirdly, due to the difficulty in collecting follow-up data caused by the epidemic situation of COVID-19, this study only collected short-term follow-up data 2 months after the end of the intervention course and could not continue to track the long-term maintenance effect. Forth, although the HTP is designed based on the theoretical framework proposed by Rickwood, we cannot guarantee that the intervention content is entirely consistent with the theoretical framework. Although Sotomayor, A. E. compiled the Special Education Career Resilience Scale (SECRS) based on CRF, the psychometric characteristics of the scale could have been better.33 Therefore, we adopted the CRS compiled by Chinese scholars, which is developed based on open-ended interviews with Chinese people with high and low career resilience. Future researchers need to develop tools more suitable for the CR of Chinese special education teachers based on CRF. In this way, verifying the consistency between the intervention plan and CRF may be more beneficial.

Moreover, special education teachers have heavy work tasks, and the intervention group members need more time and energy to share a more profound experience. The frequent occurrence of unexpected events in the school will affect the program’s progress. For example, during the program implementation, the intervention course of this week had to be canceled due to the sudden teaching inspection. Influenced by social approval, special education teachers may be more inclined to give positive feedback when participating in the focus group, thus affecting the social validity of the HTP. Finally, the sample size of this study is small. Of the initial 46 participants, six withdrew from the study. Researchers excluded these incomplete data from the statistical analysis. In order to ensure the implementation of the program, considering the workload and time conflict of special education teachers, it is also impossible to allocate the intervention group and the control group teachers by random sampling. In the future, we will need to expand the sample size, increase the quantitative indicators of the intervention effect and its social validity, and extend them to other schools to enrich further and verify the intervention program.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that implementing HTP in special education schools in China can significantly improve the professional resilience of special education teachers, and this effect can last for two months after the end of the intervention. Therefore, this program has a high degree of social effectiveness, and it is necessary to further promote and verify it in mainstream school environments or other special education school environments in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the researchers and research assistants for their help in implementing the intervention and collecting and coding data. We would also like to thank all the principals and teachers from special education schools who participated in this study.

Author Information

Dr. Jinlai Tian is an associate professor at Beihua University. Her research interests include social cognition and the social development of people with special needs. M.E. Yun Zhou is a Jilin Agricultural Science and Technology University assistant professor. Her research interests include resilience and the moral development of people with special needs. Dr. Shenggang Yu is a full professor at Beihua University. His research interests include the theory and policy of teacher development and teacher education.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Research Youth Foundation (project number: 21YJC880068) and the Educational Department of Jilin Province of China (project number: JJKH20200084SK).

Disclosure

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

References

1. Li Y, Yu JF. The influence of special education teacher’s healthy behavior and evaluative support on depression tendency: the mediating role of subjective well-being. Chin J Special Educ. 2021;4:27–33.

2. Zhao Y, Liang W, Liu TT, Zhao H. The effect of psychological resilience and burnout on subjective well-being of hearing and speech rehabilitation teachers. Chin Sci J Hear Speech Rehabil. 2021;19(3):219–222. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-4933.2021.03.015

3. Zhou YH, Liu XY. Survey of the mental health of special education teachers in Shandong Province. Chin J Special Educ. 2013;1:62–67.

4. Li X. Comparative study on mental health state between special education and primary school teachers in Sichuan Province. J Suihua Univ. 2018;38(4):120–124.

5. Li YZ. Occupational stress and job burnout among special education teachers: the moderating effect of psychological capital. Chin J Special Educ. 2014;6:78–82.

6. Luo LZ, Ge B, Qiu MY. Work stress and turnover intension of special education teachers: the chain mediating effect of emotion exhaustion and career commitment. Chin J Special Educ. 2023;1:82–89.

7. Li YZ. On the relationship between special education teacher’s emotional intelligence and work engagement. Chin J Special Educ. 2016;1:56–63.

8. Wang T, Wu HD. The effect of occupational stress on special education teacher’s turnover intentions: a moderating model. Chin J Special Educ. 2017;1:12–18.

9. Yang L, Li FF. New advances in the research into the burnout of special education teachers abroad. Chin J Special Educ. 2016;9:65–71.

10. Onuigbo LN, Eseadi C, Ugwoke SC, et al. Effect of rational emotive behavior therapy on stress management and irrational beliefs of special education teachers in Nigerian elementary schools. Medicine. 2018;97(37):1–11. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012191

11. Sharp Donahoo LM, Siegrist B, Garrett-Wright D. Addressing compassion fatigue and stress of special education teachers and professional staff using mindfulness and prayer. J School Nurs. 2018;34(6):442–448. doi:10.1177/1059840517725789

12. Tang JY, Wang Y. An analysis of the hot topics and contents of international research on special education teachers between 2016–2020. Chin J Special Educ. 2021;9:73–81.

13. Ugwoke SC, Eseadi C, Onuigbo LN, et al. A rational-emotive stress management intervention for reducing job burnout and dysfunctional distress among special education teachers: an effect study. Medicine. 2018;97(17):1–8. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010475

14. Xu X, Li XM, Zhang J, Wang W. Mental health-related stigma in China. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018;39(2):126–134. doi:10.1080/01612840.2017.1368749

15. London M. Toward a theory of career motivation. Acad Manage Rev. 1983;8(4):620–630. doi:10.2307/258263

16. Abu-Tineh AM. Exploring the relationship between organizational learning and career resilience among faculty members at Qatar University. Int J Educ Manage. 2011;25(6):635–650. doi:10.1108/09513541111159095

17. Howard F. Managing stress or enhancing wellbeing? Positive psychology’s contributions to clinical supervision. Aust Psychol. 2008;43(2):105–113. doi:10.1080/00050060801978647

18. Kodama M. Functions of career resilience against changes during working life in Japan: focus on health condition changes and task or job changes. Sage Open. 2021;11(1):1–10. doi:10.1177/215824402110021

19. Li X. The Research Structure of Managers’ Career Resilience and Its Cause and Effect. Tianjin: Nankai University; 2010.

20. Li HR, Zeng H. Review and prospect of the research on career resilience. Economic Manage. 2010;32(5):172–179.

21. Näswall K, Kuntz J, Hodliffe M, Malinen S. Employee Resilience Scale (Empres) Measurement Properties. Christchurch, New Zealand: Resilient Organizations Research Programme; 2015.

22. Watson M, McMahon M. Adult career counselling: narratives of adaptability and resilience. In: Psychology of Career Adaptability, Employability and Resilience. Cham: Springer; 2017:189–204.

23. Glavin KW, Haag RA, Forbes LK. Fostering career adaptability and resilience and promoting employability using life design counseling. In: Psychology of Career Adaptability, Employability and Resilience. Cham: Springer; 2017. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0_25

24. Hartung PJ. The career construction interview. In: Career Assessment. Brill; 2015:115–121.

25. Bimrose J, Hearne L. Resilience and career adaptability: qualitative studies of adult career counseling. J Vocat Behav. 2012;81(3):338–344. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2012.08.002

26. Kim SR, Lee SM. Resilient college students in school-to-work transition. Int J Stress Manag. 2018;25(2):195. doi:10.1037/str0000060

27. Leary KA, DeRosier ME. Factors promoting positive adaptation and resilience during the transition to college. Psychology. 2012;3(12):1215. doi:10.4236/PSYCH.2012.312A180

28. Seibert SE, Kraimer ML, Heslin PA. Developing career resilience and adaptability. Organ Dyn. 2016;45(3):245–257. doi:10.1016/j.orgdyn.2016.07.009

29. Mishra P, McDonald K. Career resilience: an integrated review of the empirical literature. Human Resource Dev Rev. 2017;16(3):207–234. doi:10.1177/153448431771962

30. Rochat S, Masdonati J, Dauwalder JP. Determining career resilience. In: Psychology of Career Adaptability, Employability and Resilience. Cham: Springer; 2017:125–141. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0_8

31. Rickwood RR. Enabling high-risk clients: exploring a career resiliency model. Available from: http://www.contactpoint.ca/natcon-conat/2OO2/pdf/pdf-O2-lO.pdf.2012.

32. Rickwood RR, Roberts J, Batten S, Marshall A, Massie K. Empowering high‐risk clients to attain a better quality of life: a career resiliency framework. J Employ Counsel. 2004;41(3):98–104. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2004.tb00883.x

33. Sotomayor AE. Career Resilience and Continuing Special Education Teachers: The Development and Evaluation of the Special Education Career Resilience Scale. College Park: University of Maryland; 2012.

34. Waddell J, Spalding K, Navarro J, Jancar S, Canizares G. Integrating a career planning and development program into the baccalaureate nursing curriculum. Part II. Outcomes for new graduate nurses 12 months post-graduation. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2015;12(1):175–182. doi:10.1515/ijnes-2015-0028

35. Li X. Research on the structure of occupational resilience and development of measuring tools. Chin J Manage. 2011;8(11):1625–1637.

36. Murta SG, de Almeida Nobre-Sandoval L, Santos Rocha VP, Vilela Miranda AA. Social validity of the strengthening families program in northeastern Brazil: the voices of parents, adolescents, and facilitators. Prev Sci. 2023;22(5):658–669. doi:10.1007/ns11121-020-01173-9

37. Leko MM. The value of qualitative methods in social validity research. Remedial Special Educ. 2014;35(5):275–286. doi:10.1177/0741932514524002

38. Wolf MM. Social validity: the case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. J Appl Behav Anal. 1978;11(2):203–214. doi:10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203

39. McDuffie KA, Scruggs TE. The contributions of qualitative research to discussion of evidence-based practice in special education. Interv Sch Clin. 2008;44:91–97. doi:10.1177/1053451208321564

40. Cutrín O, Fadden IM, Marsiglia FF, Kulis SS. Social validity in Spain of the Mantente REAL prevention program for early adolescents: social validity of mantente real in Spain. J Prev. 2022;1–22. doi:10.1007/s10935-022-00701-3

41. Kodama M. Constructs of career resilience and development of a scale for their assessment. Japan J Psychol. 2015;86(2):150–159. doi:10.4992/jjpsy.86.14204

42. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

43. Akkermans JOS, Brenninkmeijer V, Schaufeli WB, Blonk RW. It’s all about career SKILLS: effectiveness of a career development intervention for young employees. Hum Resour Manage. 2015;54(4):533–551. doi:10.1002/hrm.21633

44. Maree JG. Career construction counselling aimed at enhancing the narratability and career resilience of a young girl with a poor sense of self-worth. Early Child Dev Care. 2020;190(16):2646–2662. doi:10.1080/03004430.2019.1622536

45. Waddell J, Spalding K, Canizares G, et al. Integrating a career planning and development program into the baccalaureate nursing curriculum: part I. Impact on student’s career resilience. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2015;12(1):163–173. doi:10.1515/ijnes-2014-0035

46. Beltman S, Mansfield C, Price A. Thriving not just surviving: a review of research on teacher resilience. Educ Res Rev. 2011;6(3):185–207. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2011.09.001

47. Hodges HF, Keeley AC, Troyan PJ. Professional resilience in baccalaureate-prepared acute care nurses: first steps. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2008;29(2):80–89. doi:10.1097/00024776-200803000-00008

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.