Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 15

Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Etiology of Altered Level of Consciousness Among Patients Attending the Emergency Department at a Tertiary Hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia

Authors Adan Ali H , Farah Yusuf Mohamud M

Received 2 March 2022

Accepted for publication 20 May 2022

Published 30 May 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 5297—5306

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S364202

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Hassan Adan Ali, Mohamed Farah Yusuf Mohamud

Emergency Department, Mogadishu Somali Turkey Training and Research Hospital, Mogadishu, Somalia

Correspondence: Hassan Adan Ali, Emergency Department, Mogadishu Somali Turkey Training and Research Hospital, Mogadishu, Somalia, Tel +252615386228, Email [email protected] Mohamed Farah Yusuf Mohamud, Mogadishu Somali Turkey Training and Research Hospital, Digfer Road, Hodon, Mogadishu, Somalia, Email [email protected]

Introduction: An altered level of consciousness (ALOC) means that the patient is not as awake, alert, or able to understand or react to the surrounding environment. The main purpose of this study was to investigate the epidemiology, risk factors, and etiology of altered levels of consciousness among patients attending the Emergency Department.

Methods: The study was conducted in the Mogadishu-Somali-Turkey Training and Research Hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia, as a prospective observational study. A total of 155 adult patients with a GCS ≤ 12 were admitted to the emergency room for traumatic and non-traumatic ALOC between March and June 2021.

Results: Our study enrolled 155 (2.6%) of the 6000 patients hospitalized in the emergency room. 60% (n = 93) were males and 40% (n = 62) were females. The mean age of the participants was 46.7 ± 22.4 years. The most common presenting features were dyspnea (21.9%), injuries (20%), hemiplegia (16.8%), convulsion (16.8%), and oliguria (12.3%). 119 (77%) cases had a GCS = 3– 8, while 36 (23%) had a GCS = 9– 12. Most of the participants with ALOC had a history of hypertension (27.7%, n = 43), 34 (21.9%) had diabetes, 6 (3.9%) had epilepsy, and 4 (2.6%) had chronic renal disease. Cerebro-vascular-accidents (24.5%) were the most common cause of ALOC, followed by organ failure and traumatic brain injury (22% each), infections (12.2%), diabetic emergencies, hypoglycemia (11.6%), shock, and status epilepticus (4% each).

Conclusion: Male sex, older age, hypertension, and diabetes were the main risk factors for our study participants, while uremic encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, sepsis syndrome, and subdural hematoma were the most common causes of ALOC.

Keywords: altered level of consciousness, renal failure, cerebrovascular accident, traumatic brain injury, emergency department

Introduction

An altered level of consciousness (ALOC) is a state of reduced alertness or inability to arouse due to low awareness of the environment.1 Coma is defined as a complete lack of recognition with no response to the surroundings but intact eye-opening and no eye movement.2 Other descriptions of coma are a score of eight on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) or a score of U on the AVPU (Alert, responsive to Voice, responsive to Pain, Unresponsive) scale.3 The predisposing factors of ALOC include hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and chronic organ failure.4 The causes of ALOC were sub-divided into two categories: traumatic (such as a brain injury) and non-traumatic (such as neurological disorders, metabolic diseases, diffuse physiological malfunction of the brain (such as epilepsy or drugs), and psychiatric or functional disorders).5 Emergency room (ER) admissions for ALOC patients represent 6% of all new patients.6 A study performed in Nigeria showed that medical coma accounted for 9.8% (200/2033) of emergency room visits and 3.1% (200/6548) of total hospital admissions.7 The mortality of altered level of consciousness patients in ER is high and strongly related to the underlying cause.8 To our knowledge, there is no study about the epidemiological characteristics, risk factors, and etiology of ALOC in Somalia. The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the epidemiology, risk factors, and etiology of altered levels of consciousness among patients attending the Emergency Department at a Tertiary Hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia.

Method

The study was a prospective observational study done in Mogadishu Somali Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdogan Training and Research Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia. Consecutive adults admitted as the traumatic and non-traumatic ALOC patients who arrived at the emergency room between March 2021 and June 2021 with a GCS 12 or below were prospectively included.9 Young patients (<15 years of age), pregnant women, acute confusion states (delirium), and patients with no definitive diagnosis were excluded from our study.

An altered level of consciousness (ALOC) means that the patient is not as awake, alert, or able to understand or react to the surrounding environment.10 One hundred and fifty-five patients had met the criteria of ALOC. We used a questionnaire-based formula to collect data, and we categorized it into 1) socio-demographic factors including age, gender, and previously known chronic diseases. 2) Clinical presentations included dyspnea, convulsion, fever, oliguria, hemiplegia, diarrhea/vomiting, and injuries. 3) Laboratory investigations included serum blood glucose, arterial blood gases, complete blood count, liver function tests, renal function testing, serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and chloride), urine analysis, serum procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein for every ALOC patient admitted to the emergency department. 4) We also evaluated imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) of the head first for every unconscious patient with neurological findings to exclude brain hemorrhage. If the brain CT and laboratory data are unremarkable, we concluded brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the possibility of ischemic stroke. We performed a whole-body CT scan of the head, cervical, thoracic, and abdominopelvic regions for patients with trauma-induced unconsciousness. 4) We performed a chest x-ray, echocardiogram, abdomen, and blood vessels (Doppler) ultrasound as required. 5) The last question of our questionnaire was the etiology of ALOC based on the Glasgow coma scale (GCS), while the diagnostic criteria of ALOC are summarized in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Common Etiologies of ALOC and Their Diagnostic Criteria |

The study was approved by the local ethical committee board of Mogadishu Somali Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdogan Training and Research Hospital with a reference number of MSTH/5198, and written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s relatives.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences application was used to conduct statistical analyses (SPSS version 23.0). The mean and standard deviation of numeric variables had presented. Percentages had used to represent nominal variables. Cross tabulation had utilized to examine differences across groups and determine the cause of ALOC. Fisher's exact test was utilized for categorical variables to compare patient characteristics between groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

155 (2.6%) out of 6000 patients admitted to the emergency unit had enrolled in our study. 60% (n = 93) were males and 40% (n = 62) were females. The mean age of the participants was 46.7 (SD± 22.4) years with the minimum and the maximum age was 15–91 years. According to the age group, 39 (25.2%) patients were in between 15 and 25 years, 36 (23.2%) patients were 26–45 years, 29 (18.7%) patients were 46–60 years, while 51 (32.9%) patients were >60 years with male predominance 31 out of 51 cases and this age group constitutes the most respondents of this study.

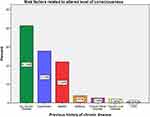

Figure 1 summarizes the risk factors of ALOC among participants. Most (27.7%, n = 43) of participants with ALOC had a history of hypertension. 34 (21.9%) had diabetes, 6 (3.9%) had epilepsy, 4 (2.6%) chronic renal disease (CRD), 3 (1.9%) chronic liver disease (CLD), and 1 (0.6%) had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Nearly half of the participants (41.3%, n = 64) had no risk factor.

|

Figure 1 Risk factors of ALOC among participants. |

The most common presenting features were dyspnea 34 (21.9%), injuries 31 (20%), hemiplegia 26 (16.8%), convulsion 26 (16.8%), oliguria 19 (12.3%), fever 17 (11%), and diarrhea/vomiting 2(1.3%). Among the 155 participants, their Glasgow coma scale (GCS) had distributed as follows: 26 (16.8%) respondents had a GCS = 3, 93 (60%) respondents had a GCS 4–8, this constituted the most frequency group, and 36 (23.2%) respondents had moderate GCS 9–12.

In our diagnostic method, 112 (72.3%) cases had a chest x-ray, 94 (60.6%) cases had a brain CT, 32 (20.6%) cases had a neck CT, 38 (24.5%) cases had thorax CT, 40 (25.8%) cases had abdominopelvic CT, 19 (12.3%) cases had brain MRI, 15 (9.4%) cases had echocardiography, 50 (32.3%) cases had abdominal USG, and 13 (8.4%) cases had Doppler USG (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Distribution of Age, Gender, Risk Factors, Clinical Features, GCS, Radiology and Etiology |

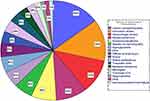

A total of 13 non-traumatic (medical) and 5 traumatic causes of ALOC are summarized in Figure 2; these include 23 (14.8%) with uremic encephalopathy, 21 (13.5%) with ischemic stroke, 17 (10.9%) with hemorrhagic stroke, 15 (9.7%) with sepsis syndrome, 12 (7.7%) subdural hematoma, 10 (6.5%) with diabetic emergencies (DKA & HHS), 9 (5.8%) with hepatic encephalopathy, 8 (5.2%) with hypoglycemia, 7 (4.5%) with diffuse axonal injury, 6 (3.9%) with status epileptics, 6 (3.9%) with shock, 6 (3.9%) with traumatic SAH, 4 (2.6) % with epidural hematoma, 4 (2.6%) with meningitis, 3 (1.9%) traumatic ICH, 2 (1.3%) with hyponatremia, and 2 (1.3%) with decompensated heart failure (DHF).

|

Figure 2 Etiology of altered level of consciousness among participants. |

According to the laboratory results, the majority of ALOC patients showed respiratory alkalosis, increased serum creatinine, urea, AST, ALT, CRP, and Procalcitonin. PH, HCO3, Creatinine, Urea, AST, ALT, CRP, and Procalcitonin mean 7.630.41, 17.640.55, 13.570.34, 97.678.80, 167.4929.98, 166.6632.92, 88.998.21, and 3.630.67, respectively, as shown in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Laboratory Findings of the Respondents |

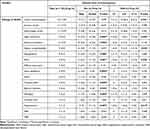

As indicated in Table 4, uremic encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, subdural hematoma, status epilepticus, DKA, diffuse axonal damage, traumatic SAH, epidural hematoma, and meningitis were all more common in men, while sepsis syndrome, shock, traumatic ICH, and hyponatremia were female predominant. Hypoglycemia, HHS, and decompensated HF had distributed equally.

|

Table 4 Etiological Correlation of ALOC by Sex and GCS |

Sepsis syndrome, subdural hematoma, hypoglycemia, DKA, status epilepticus, traumatic SAH, epidural hematoma, meningitis and hyponatremia were showed significant association with gender (p < 0.000**, p < 0.050*, p < 0.008*, p < 0.001*, p < 0.000*, p < 0.000**, p < 0.016*, p < 0.004*, and p < 0.007*), respectively.

For GCS = 3, the association between an ALOC and GCS showed that 5 (3.2%) patients had sepsis syndrome, 5 (3.2%) cases had an ischemic stroke, 3 (1.9%) cases had a hemorrhagic stroke, 2 (1.2%) cases had uremic encephalopathy, and 2 (1.2%) had hypoglycemia. A GCS of 4–8, on the other hand, indicated that 13 (8.4) patients had uremic encephalopathy, 13 (8.4) patients had a hemorrhagic stroke, 9 (5.8) patients had an ischemic stroke, 9 (5.8) patients had sepsis, 6 (3.9) patients had a subdural hematoma, and 6 (3.9) patients had a diffuse axonal injury. While those with GCS = 9–12 were 5.2% (n = 8), 4.5% (n = 7), 3.2% (n = 5), 3.2% (n = 5), and 1.9% (n = 3), uremic encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, subdural hematoma, DKA, and hepatic encephalopathy, respectively (Table 4).

Uremic encephalopathy, sepsis syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, DKA, and hyponatremia were significantly associated with GCS (p < 0.04*, p < 0.05*, p < 0.022*, p < 0.026*, and p < 0.014*), respectively.

Table 5 shows that the majority of the study respondents (n = 91, 58.7%) had a one or more comorbidities. Most of the respondent (n = 43, 27.7%) had hypertension, followed by diabetes (n = 34, 22%), and epilepsy (n = 6, 3.9%). 27 (17.4%) patients with hypertension were predominant in the age older than 60 years, followed by the age group of 26–45 and 46–60 (n = 7, 4.5% each). On the other hand, diabetes was more common in patients with age of 60 years and 46–60, 11% and 10.7%, respectively.

|

Table 5 Correlation Between Risk Factors and Age Group Among Patients with ALOC |

A strong significant association was found between risk factor of hypertension and age group (P = 0.000**) and also diabetes and age group (P = 0.000**).

Discussion

There are several admissions for ALOC to the emergency room (ER) due to trauma-related unconsciousness such as subdural hematoma and non-trauma (medical coma) cases like uremic encephalopathy, Cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and sepsis syndrome. The diagnosis of ALOC had reached using family history, physical examinations including GCS, medical pictures (brain CT scan, brain MRI, USG, and chest x-ray), and the results of laboratory tests.

In the present study, we found that 2.6% of ALOC patients had been admitted to the emergency department during a four-month study period. Similar to our report, William et al reported that approximately 5% of unconscious patients visited the emergency room within four months.27 Our study excluded all unconscious patients with their GCS >12 and acute confusional state, in contrast to William and his colleagues’ study.27

The mean age of our study participants was 46.7 ± 22.4 years, while >60 years of the age group constituted the uppermost and most cases were male sex (60%), specifically older males. A study with the same focus performed by Nasution et al showed that the mean age was 41.65 ± 19.5 years old, 57.8% were males, and most study participants were older males.6

Data carried out in Nigeria showed that male sex, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and substance abuse, positive hepatitis B virus (HBV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were the most common risk factors among ALOC patients.7 In the current study, sixty percent of ALOC patients had at least one risk disease involving hypertension, diabetes, epilepsy, chronic renal disease, chronic liver disease, and COPD. There are a few differences between the two studies, substance abuse (alcohol) and HIV were not common in our study population. In the current study, there is a significant link between ALOC and hypertension and also ALOC and diabetes (P < 000** each) as shown in Table 5.

According to Volk and his friend’s study, the most common clinical symptoms in our report were dyspnea 34 (21.9%), injuries 31 (20%), hemiplegia 26 (16.8%), convulsion 26 (16.8%), oliguria 19 (12.3%), fever 17 (11%), and diarrhea/vomiting 2 (1.3%).28

According to the severity of ALOC patients based on GCS, a Munich study found that 15% had a GCS 3–8 and 23% had a GCS 9–12 but had not been classified as etiology-based GCS.28 In contrast to the previous study, in the present study, 119 (77%) cases had a GCS = 3–8, while the remaining 36 (23%) had a GCS = 9–12. Most of our cases were organ failure-induced ALOC (22%, n = 34), cerebrovascular accident (24.5%, n = 38), and traumatic brain injury (20.6%, n = 32).

In the current study, the most common causes of altered level of consciousness were cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) (24.5%), organ failure (OF) and traumatic brain injury (22% each), infections (12.2%), diabetic emergencies and hypoglycemia (11.6%), and shock and status epilepticus (4% each). To consider a study from Nigeria, four common causes of ALOC were acute stroke, diabetic crises, uremic encephalopathy, and infections; 33%, 12.5%, 11%, and 11%, respectively.7 Another report from Sweden revealed 24% had a focal neurological lesion (stroke), 21% had metabolic disturbance, 12% had epileptic coma.29 A similar study appeared cerebrovascular disorders were the most trusted causes of ALOC (24%), particularly ischemic stroke was uppermost in this group, followed by infections (14%), metabolic and cardiovascular disease (13%), epileptic seizures (12%), and trauma (2%).28 In trauma-related ALOC, there is a considerable difference between our study and other studies from developed countries since our country has high rates of explosions, gunshot, and road traffic accidents, while developed countries (Germany) have no or low rate explosions and gunshots. So our study discovered a high prevalence of trauma-related ALOC which constituted 22% (n = 32) when compared to the study from Germany 2% (n = 4).28

There are two strengths of our study results. First, we measured the association between the GCS and the etiological distribution of ALOC. We demonstrated that patients with a GCS 4–8 had uremic encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, sepsis syndrome, subdural hematoma, and diffuse axonal injury. Second, we looked at the link between ALOC etiological distributions and sex. Uremic encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, subdural hematoma, status epilepticus, diffuse axonal damage, traumatic SAH, epidural hematoma, and meningitis were the most common male cases. Sepsis syndrome, shock, traumatic ICH, and hyponatremia had predominant in females, while diabetic crises and decompensated HF were shown to have equal sex distribution.

Our study has several limitations; first, the study had done in a single tertiary hospital that cannot represent the clear image of ALOC in our target population. Second, the duration of our study was four months which was not enough to reach conclusive results. Third, the sample size of our cases was 155 which is relatively small. Finally, some parameters that did not examine (intoxications, body mass index (BMI), and smoking), as well as pregnancy and acute confusional state or delirium, were excluded.

Conclusion

The current study sheds light on the risk factors and etiology of ALOC. Male sex, older age, hypertension, diabetes, and trauma were the main risk factors for our study participants. The severity of the patients with ALOC based on GCS, 119 (77%) cases had a GCS = 3–8 which constitutes the uppermost level. The most common causes of ALOC in the adult patients admitted to the ER were uremic encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, sepsis syndrome, and subdural hematoma.

Recommendation

Our study suggests that men and older people initiate lifestyle changes and maintain a careful follow-up to their health. Also, we prose to practice preventive measures and attend regular medical checkups among patients with chronic diseases including systemic hypertension, diabetes, epilepsy, and COPD. Finally, we recommend performing original research about predisposing variables, the pathogenesis of renal failure, and renal replacement method in Somalia since renal failure was the most common cause of ALOC.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

We obtained an approval letter from the review board of Mogadishu Somali Turkey Training and Research Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s relatives during the data collection and they signed the consent form. We declare that we have followed the protocols of our work center. Patient data confidentiality was respected.

Disclosure

We declare that we have no competing interests in this work.

References

1. Reichhart MD, Meuli R. Alterations of level of consciousness related to stroke. Behav Cognitive Neurol Stroke. 2013;4:312.

2. Kondziella D, Bender A, Diserens K, et al. European Academy of Neurology guideline on the diagnosis of coma and other disorders of consciousness. Eur j Neurol. 2020;27(5):741–756. doi:10.1111/ene.14151

3. McNarry AF, Goldhill DR. Simple bedside assessment of level of consciousness: comparison of two simple assessment scales with the Glasgow Coma scale. Anaesthesia. 2004;59(1):34–37. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03526.x

4. Wang J, Li Z, Yu Y, Li B, Shao G, Wang Q. Risk factors contributing to postoperative delirium in geriatric patients postorthopedic surgery. Asia Pacific Psychiatry. 2015;7(4):375–382. doi:10.1111/appy.12193

5. Cooksley T, Rose S, Holland M. A systematic approach to the unconscious patient. Clin Med. 2018;18(1):88. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.18-1-88

6. Nasution AH, Prima A. Incidence of loss of consciousness in critically ill patients referred to anesthesiologist in emergency department. Asian J Infect Dis. 1979;3(1):41–44.

7. Obiako OR, Oparah S, Ogunniyi A. Causes of medical coma in adult patients at the University College Hospital, Ibadan Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2011;18(1):1–7.

8. Völk S, Koedel U, Pfister HW, Schwankhart R. Impaired consciousness in the emergency department. Eur Neurol. 2018;80(3–4):179–186. doi:10.1159/000495363

9. Hoffmann F, Schmalhofer M, Lehner M, Zimatschek S, Grote V, Reiter K. Comparison of the AVPU scale and the pediatric GCS in prehospital setting. Prehospital em Care. 2016;20(4):493–498. doi:10.3109/10903127.2016.1139216

10. Simon B, Nobay F. 12 altered mental status. An introduction to clinical emergency medicine: guide for practitioners in the emergency department. Clin Emerg Med. 2005;1:179.

11. Rosner MH, Husain-Syed F, Reis T, Ronco C, Vanholder R. Uremic encephalopathy. Kidney Int. 2021;1:58.

12. Hankey GJ. Stroke. Lancet. 2017;389(10069):641–654. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30962-X

13. Shetty A, Macdonald SP, Keijzers G, et al. Sepsis in the emergency department–part 2: investigations and monitoring. Em Med Australasia. 2018;30(1):4–12. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.12924

14. Blei AT. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;14(6):959–974. doi:10.1053/bega.2000.0141

15. Burrows CF, Taboada J. Liver disorders 9. Clin Med Dog Cat. 2009;1:397.

16. Mathew P, Thoppil D. Hypoglycemia. StatPearls; 2021.

17. Yehia BR, Epps KC, Golden SH. Diagnosis and management of diabetic ketoacidosis in adults. Hosp Physician. 2008;35:21–26.

18. Muneer M, Akbar I. Acute metabolic emergencies in diabetes: DKA, HHS and EDKA. In: Diabetes: From Research to Clinical Practice. Cham: Springer; 2020:85–114.

19. Carlson B, Fitzsimmons L. Shock, sepsis, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Priorities Critical Care Nursing-E-Book. 2019;2:474.

20. Brophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17(1):3–23. doi:10.1007/s12028-012-9695-z

21. Lee SK. Diagnosis and treatment of status epilepticus. J Epilepsy Res. 2020;10(2):45. doi:10.14581/jer.20008

22. Bamberger DM. Diagnosis, initial management, and prevention of meningitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(12):1491–1498.

23. Mount HR, Boyle SD. Aseptic and bacterial meningitis: evaluation, treatment, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5):314–322.

24. Greenberg B. Acute decompensated heart failure – treatments and challenges. Circulation J. 2012;76(3):532–543. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0130

25. Alagiakrishnan K, Banach M, Jones LG, Datta S, Ahmed A, Aronow WS. Update on diastolic heart failure or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the older adults. Ann Med. 2013;45(1):37–50. doi:10.3109/07853890.2012.660493

26. Alagic Z, Eriksson A, Drageryd E, Motamed SR, Wick MC. A new low-dose multi-phase trauma CT protocol and its impact on diagnostic assessment and radiation dose in multi-trauma patients. Emerg Radiol. 2017;24(5):509–518. doi:10.1007/s10140-017-1496-4

27. Kanich W, Brady WJ, Huff JS, et al. Altered mental status: evaluation and etiology in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(7):613–617. doi:10.1053/ajem.2002.35464

28. Völk S, Koedel U, Pfister HW, Schwankhart R. Impaired consciousness in the emergency department. Eur Neurol. 2018;80(3–4):179–186.

29. Forsberg S, Höjer J, Enander C, Ludwigs U. Coma and impaired consciousness in the emergency room: characteristics of poisoning versus other causes. Em Med J. 2009;26(2):100–102. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.054536

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.