Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 11

Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole once-monthly in obese and nonobese patients with schizophrenia: a post hoc analysis

Authors De Hert M, Eramo A, Landsberg W, Kostic D, Tsai L, Baker RA

Received 7 January 2015

Accepted for publication 12 March 2015

Published 27 May 2015 Volume 2015:11 Pages 1299—1306

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S80479

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Marc De Hert,1 Anna Eramo,2 Wally Landsberg,3 Dusan Kostic,4 Lan-Feng Tsai,5 Ross A Baker4

1Department of Neurosciences, KU Leuven, Belgium; 2Lundbeck LLC, Deerfield, IL, USA; 3Otsuka Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd., Wexham, UK; 4Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA; 5Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA

Purpose: To assess the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (AOM 400), an extended-release injectable suspension of aripiprazole, in obese and nonobese patients.

Patients and methods: This post hoc analysis of a 38-week randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, noninferiority study (NCT00706654) compared the clinical profile of AOM 400 in obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥30 kg/m2) and nonobese (BMI <30 kg/m2) patients with schizophrenia for ≥3 years. Patients were randomized 2:2:1 to AOM 400, oral aripiprazole 10–30 mg/d, or aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (AOM 50 mg) (subtherapeutic dose). Within obese and nonobese patient subgroups, treatment-group differences in Kaplan–Meier estimated relapse rates at week 26 (z-test) and in observed rates of impending relapse through week 38 (chi-square test) were analyzed. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) (>10% in any treatment group) were summarized.

Results: At baseline of the randomized phase, obesity rates were similar among patients randomized to AOM 400 (n=95/265, 36%), oral aripiprazole (n=95/266, 36%), and AOM 50 mg (n=43/131, 33%). In both obese and nonobese patients, relapse rates through week 38 for patients randomized to AOM 400 (obese, 7.4%; nonobese, 8.8%) were similar to those in patients on oral aripiprazole (obese, 8.4%; nonobese, 7.6%), whereas relapse rates were significantly lower with AOM 400 versus AOM 50 mg (obese, 27.9% [P=0.0012]; nonobese, 19.3% [P=0.0153]). The most common TEAEs with AOM 400 in obese and nonobese patients were insomnia (12.6% and 11.2%), headache (12.6% and 8.2%), injection site pain (11.6% and 5.3%), akathisia (10.5% and 10.6%), upper respiratory tract infection (10.5% and 4.7%), weight increase (10.5% and 8.2%), and weight decrease (6.3% and 11.8%). Within the AOM 400 group, 7.6% of patients who were nonobese at baseline became obese, and 17.9% of obese patients became nonobese during randomized treatment.

Conclusion: The clinical profile of AOM 400 was similar in obese and nonobese patients.

Keywords: antipsychotic, long-acting injectable, schizophrenia, obesity, aripiprazole once-monthly

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic psychiatric disorder in which long-term antipsychotic treatment is recommended to reduce the risk of relapse.1,2 Many second-generation antipsychotics are associated with metabolic side effects such as weight gain.1,3–7 Patients with schizophrenia often have comorbid medical conditions that may require continuous monitoring in addition to being observed for potential medication side effects.1,6,8,9 In a national survey of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition discharge codes for patients hospitalized for schizophrenia, 63% of patients who had schizophrenia as their primary diagnosis had ≥1 comorbid condition.10 Metabolic risk factors, such as obesity, are also prevalent among patients with schizophrenia. A national, voluntary, cardiometabolic screening program of >10,000 patients in US public mental health clinics found that 53% of patients with schizophrenia were obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥30.0 kg/m2).11

Aripiprazole is an atypical antipsychotic with partial agonist activity at dopamine D2 receptors12 and a potentially less burdensome metabolic profile compared with other atypical antipsychotics.4,13,14 A once-monthly, long-acting injectable (LAI) formulation, aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (AOM 400), is approved for the treatment of schizophrenia,15–17 making it the first dopamine D2 receptor partial agonist available in a long-acting formulation. Given the prevalence of obesity in patients with schizophrenia, it is important to consider the need for dose adjustments or special consideration in obese patients. Other LAI antipsychotics, such as paliperidone palmitate, may require dose increases for overweight or obese patients with schizophrenia.18 This brief communication reports results from a post hoc analysis that evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of AOM 400 in obese and nonobese patients with schizophrenia to provide guidance on whether dose adjustments may be needed.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

Data are from a 38-week double-blind, multicenter, international, active-controlled study that examined the clinical profile of AOM 400 as maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia. The study was conducted from September 2008 through August 2012 and recruited patients from Austria, Belgium, Chile, Croatia, Estonia, France, Hungary, Italy, Poland, South Africa, South Korea, Thailand, and the United States. Study design and patient inclusion/exclusion criteria were previously described in detail.13 Briefly, adult patients aged 18–60 years with a diagnosis of schizophrenia based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision criteria for ≥3 years and a history of symptom exacerbation when not receiving antipsychotic treatment were eligible for study inclusion. The study had three treatment phases, including an oral conversion phase (phase 1, cross-titration to oral aripiprazole and discontinuation of other antipsychotic) and an oral aripiprazole stabilization phase (phase 2). Patients who met the stability criteria with oral aripiprazole for 8 consecutive weeks entered the double-blind, active-controlled phase (phase 3, up to 38 weeks) in which patients were randomized 2:2:1 to AOM 400; oral aripiprazole (10–30 mg/d); or aripiprazole once-monthly 50 mg (AOM 50 mg), a subtherapeutic dose included for assay sensitivity. Using a double-dummy design, patients in all treatment groups (including oral aripiprazole) received an injection into the gluteal muscle. Per protocol, patients whose BMI was ≤28 kg/m2 received injections with a 21-gauge, 1.5-inch needle, and patients whose BMI was >28 kg/m2 received injections with a 21-gauge, 2-inch needle.16 Patients were able to reduce their AOM dose to 300 mg (or 25 mg in the AOM 50 mg group) for tolerability reasons and then subsequently increase their dose to 400 mg (or 50 mg in the AOM 50 mg group) on one occasion, if considered appropriate.13

Assessments and statistical analyses

The primary endpoint – the noninferiority of AOM 400 to oral aripiprazole based on the Kaplan–Meier estimate of impending relapse rate at week 26 – was met, and results were previously described in detail.13 The current report is based on an exploratory post hoc analysis that was conducted in the subpopulations of obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and nonobese (BMI <30 kg/m2) patients, as determined at baseline of the double-blind phase. Estimated impending relapse rates at week 26 and the observed rate of impending relapse at week 38 were assessed. Impending relapse was defined as meeting ≥1 of the following criteria: (1) Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale score of ≥5 (minimally worse) and either an increase on any of four individual Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) items (conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, suspiciousness, or unusual thought content) to a score >4 with an absolute increase of ≥2 on that specific item since randomization, or an increase to >4 on one of those PANSS items and an absolute increase of ≥4 on the combined score of those items; (2) hospitalization due to worsening of psychotic symptoms; (3) Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Suicidality score of four (severely suicidal) or five (attempted suicide) on part 1 and/or six (much worse) or seven (very much worse) on part 2; or (4) violent behavior resulting in clinically relevant self-injury, injury to another person, or property damage.13

Estimated impending relapse rate at week 26 was calculated using Kaplan–Meier estimates, calculated as one – proportion of patients free of impending relapse events, using the intent-to-treat population, which included all patients randomized to double-blind treatment. Standard errors were calculated using Greenwood’s formula. Within obese and nonobese subgroups, treatment-group differences in estimated relapse rates at week 26 and in observed rates of impending relapse through week 38 were analyzed using z-tests and chi-square tests, respectively.

To assess tolerability, the most common (>10% incidence in any treatment group) treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were summarized within treatment groups in obese and nonobese patients; no formal statistical analyses were conducted. Within treatment groups (AOM 400, AOM 50 mg, and oral aripiprazole 10–30 mg) the number and percentage of patients who went from obese to nonobese, and from nonobese to obese, from baseline of the double-blind phase to the end of the study were calculated. Mean change from baseline to study end on total scores of extrapyramidal symptom scales (EPS), including the Simpson–Angus Scale19 total score, Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale20 global score, and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale21 rating score, were assessed among treatment groups for obese and nonobese patients. Metabolic parameters (ie, fasting total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol, fasting triglycerides, and fasting glucose) were monitored, and descriptive statistics, including mean change from baseline to study end, were calculated for obese and nonobese subgroups. For mean weight change from baseline to study end, treatment group comparisons within obese and nonobese subgroups were analyzed using an analysis of a covariate model with baseline as a covariate.

Results

Patient disposition and characteristics

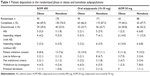

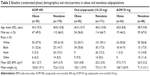

Patient disposition was previously described in detail (Table 1). Briefly, 662 patients were randomized to phase 3 double-blind treatment; 233 (35.2%) patients were obese at randomization. Sixty-four percent of randomized obese patients completed the study, and 67% of nonobese patients completed the study. Within the AOM 400 treatment group, a numerically larger percentage of obese patients discontinued from the study compared with nonobese patients (30.5% vs 23.5%, respectively; Table 1), although rates of discontinuation due to impending relapse (with or without an adverse event) were numerically comparable between obese and nonobese patients (Table 1). In both obese and nonobese subpopulations, baseline and demographic characteristics were comparable among treatment groups (Table 2). Obese patients were slightly older than nonobese patients. Across treatment groups, Asian patients and men were overrepresented in the nonobese subpopulations, and more black participants were in the obese subpopulations compared with other races.

Efficacy

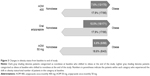

At week 26, the estimated relapse rate with AOM 400 was comparable to that of oral aripiprazole in obese patients (6.5% vs 7.9%, respectively; difference, −1.4; 95% CI, −8.93 to 6.21; P=0.7253) and significantly lower with AOM 400 versus AOM 50 mg (6.5% vs 30.2%, respectively; difference, −23.7; 95% CI, −39.60 to −7.80; P=0.0035) in obese patients. In nonobese patients, the estimated relapse rate at week 26 with AOM 400 was also comparable to that of oral aripiprazole (7.4% vs 7.7%, respectively; difference, −0.2; 95% CI, −6.04 to 5.60; P=0.9412) and significantly lower with AOM 400 versus AOM 50 mg (7.4% vs 17.2%, respectively; difference, −9.8; 95% CI, −19.29 to −0.33; P=0.0426). At week 38, the observed rate of impending relapse with AOM 400 was similar to that observed with oral aripiprazole and significantly lower compared with AOM 50 mg in obese and nonobese patients (P=0.0012 and P=0.0153, respectively; Figure 1).

Safety

The tolerability profile of AOM 400 was similar in obese and nonobese patients with schizophrenia. Most TEAEs (>10% incidence in any treatment group) were comparable between obese and nonobese patients within and between treatment groups (Figure 2). Rates of injection site pain, reported as a TEAE, were higher in obese versus nonobese patients who received AOM 400 (11.6% vs 5.3%, respectively); however, no patient discontinued because of injection site pain. EPS scales showed no differences between obese and nonobese patients (data not shown) and were consistent with the results from the full study.13 The incidence of potentially clinically relevant weight changes, defined a priori as a ≥7% increase or decrease in weight, and mean weight changes from baseline to study end are listed by treatment group for obese versus nonobese patients in Table 3. At week 38, mean weight change was comparable in nonobese patients treated with AOM 400 versus oral aripiprazole. However, the difference in mean (SD) weight change between nonobese patients treated with AOM 400 compared with AOM 50 mg was statistically significant (0.7 [4.2] vs −1.0 [0.4] kg, respectively; P<0.05; Table 3). In obese patients, mean weight change at week 38 was comparable between AOM 400 and oral aripiprazole and between AOM 400 and AOM 50 mg (Table 3).

Of note, in patients treated with AOM 400, a numerically greater percentage of obese patients had weight loss ≥7% than had weight gain ≥7% (17.9% vs 10.5%, respectively). Within the AOM 400 treatment group, 7.6% of patients went from nonobese at baseline to obese at study end, whereas 17.9% of patients treated with AOM 400 went from obese at baseline to nonobese at study end. In the AOM 50 mg and oral aripiprazole 10–30-mg treatment groups, percentages for patients who went from obese to nonobese and from nonobese to obese were similar to those seen in the AOM 400 treatment arm (Figure 3).

Across all treatment groups, mean changes from baseline were minimal in metabolic parameters, including fasting total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose, although the variation was large within groups (Table 3). In obese and nonobese patients treated with AOM 400, all mean changes were less than 4% of baseline values at week 38, with the exception of triglycerides in nonobese patients (mean ± SD increase 11.0±79.4 mg/dL from baseline mean of 119.6 mg/dL, n=118). In addition, mean ± SD increases in triglycerides (28.4±53.9 mg/dL; baseline 115.9 mg/dL) and glucose (11.4±53.1 mg/dL; baseline 99.4 mg/dL) were observed at week 38 in obese patients who received AOM 50 mg (n=14).

Discussion

The tolerability profile of AOM 400 was comparable between obese and nonobese patients with schizophrenia. Overall, efficacy outcomes were comparable between obese and nonobese patients treated with AOM 400; few patients went from nonobese to obese over the course of the study, and mean metabolic parameters remained relatively stable. The primary efficacy outcome – the noninferiority of Kaplan–Meier estimated impending relapse rate at week 26 – was met in obese and nonobese subpopulations despite the loss of power when dividing the full sample, demonstrating that AOM 400 was efficacious in both subpopulations. Although statistical analyses comparing the primary outcome between obese and nonobese patients were not conducted, and the study was not specifically powered for this post hoc subgroup analysis, estimated impending relapse rates with aripiprazole 400 mg at week 26 were low and numerically comparable between obese and nonobese patients (6.5% and 7.4%, respectively). Similar results were reported in a post hoc analysis of risperidone LAI in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were followed for ≤24 months.22 Specifically, efficacy outcomes (ie, time to hospitalization, PANSS total score, and the Heinrichs–Carpenter Quality of Life Scale) were comparable between risperidone LAI and oral antipsychotics in subgroups of obese (≥30 kg/m2) and nonobese patients.22 In contrast to other LAI antipsychotics that may require dose adjustments for obese patients,18 the comparable efficacy and tolerability profile of AOM 400 in obese and nonobese patients with schizophrenia supports the idea that no weight-based dose adjustments are required for AOM therapy.

Because of the association between antipsychotic use and metabolic changes,1,3–7 patients should be continually monitored for weight gain and obesity-related long-term health problems (eg, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes)6 while receiving maintenance therapy.1,5 Analyses of metabolic changes with olanzapine LAI in patients with schizophrenia found that 5.9% of patients who were obese at baseline of randomization (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) had a clinically significant (≥7%) increase in body weight at 24 weeks (data were not reported separately for nonobese patients).23 In a post hoc analysis of metabolic changes with paliperidone palmitate treatment in patients with schizophrenia, greater percentages of underweight and normal-weight patients shifted toward higher BMI categories than overweight and obese patients who shifted to lower BMI categories.24 From baseline to endpoint of the open-label 52-week extension study, 15% of normal-weight patients (BMI 19–<25 kg/m2), 4% of overweight patients (BMI 25–<30 kg/m2), and 6% of obese patients (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) had a ≥7% increase in body weight. Although weight was categorized differently in the study reported here (ie, nonobese patients were not separated into normal and overweight categories), a similar pattern was observed, in that a higher percentage of nonobese patients had ≥7% weight gain compared with obese patients. Notably, a greater percentage of patients went from obese to nonobese than from nonobese to obese with AOM 400 treatment. The rate of injection site pain, reported as a TEAE, was notably lower in nonobese patients compared with obese patients (5.3% vs 11.6%, respectively). The lower rate in nonobese patients may be secondary to the use of a shorter needle in most nonobese patients (21-gauge, 1.5-inch needle for patients whose BMI was ≤28 kg/m2, and 21-gauge, 2-inch needle for patients whose BMI was >28 kg/m2). Among other TEAEs of interest, changes on EPS rating scales and rates of akathisia reported as TEAEs were comparable between obese and nonobese patients.

Conclusion

In obese and nonobese patients with schizophrenia, the tolerability profile of AOM 400 was comparable. AOM 400 also demonstrated comparable efficacy in obese and nonobese patients with schizophrenia. Furthermore, the percentage of patients who went from obese to nonobese was higher than the percentage of patients who went from nonobese to obese. Changes in weight parameters from the safety analyses are consistent with the metabolic profile of oral aripiprazole.3,4 Nevertheless, weight gain is a common side effect of antipsychotic therapy,1 and clinical guidelines recommend continuous monitoring of metabolic changes and other medication side effects in all patients undergoing treatment with atypical antipsychotic therapy.1,5

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., and H Lundbeck A/S. Editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Amy Roth Shaberman, PhD, of C4 MedSolutions, LLC (Yardley, PA, USA), a CHC Group company, with funding from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Commercialization & Development, Inc., and H Lundbeck A/S.

Disclosure

Marc De Hert has been a consultant for, received grant/research support and honoraria from, and been on the speakers/advisory boards of Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck SA, Otsuka, and Takeda. Anna Eramo is an employee of Lundbeck LLC. Wally Landsberg is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd. Lan-Feng Tsai, Dusan Kostic, and Ross Baker are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al; WFSBP Task force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(1):2–44. | ||

Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, Dixon LB; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):94–103. | ||

Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):31–41. | ||

Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;123(2–3):225–233. | ||

Dixon L, Perkins D, Calmes C. Guideline Watch (September 2009): Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia; 2009. Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/schizophrenia-watch.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2015. | ||

De Hert M, Detraux J, van Winkel R, Yu W, Correll CU. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(2):114–126. | ||

De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, Kahl KG, Holt RI, Moller HJ. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(6):412–424. | ||

De Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(2):138–151. | ||

De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52–77. | ||

Weber NS, Cowan DN, Millikan AM, Niebuhr DW. Psychiatric and general medical conditions comorbid with schizophrenia in the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(8):1059–1067. | ||

Correll CU, Druss BG, Lombardo I, et al. Findings of a U.S. national cardiometabolic screening program among 10,084 psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(9):892–898. | ||

Burris KD, Molski TF, Xu C, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302(1):381–389. | ||

Fleischhacker WW, Sanchez R, Perry PP, et al. Aripiprazole once-monthly for treatment of schizophrenia: double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority study. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(2):135–144. | ||

Kane JM, Sanchez R, Perry PP, et al. Aripiprazole intramuscular depot as maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia: a 52-week multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(5):617–624. | ||

Abilify Maintena® US. aripiprazole. Tokyo, Japan: Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; 2013. | ||

Abilify Maintena® EU. aripiprazole. Wexham, UK: Otsuka Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd.; 2013. | ||

Abilify Maintena™ CAN. aripiprazole. Saint-Laurent, QC, Canada: Otsuka Canada Pharmaceutical Inc.; 2014. | ||

Xeplion®. paliperidone palmitate. Beerse, Belgium: Janssen Pharmaceutica N.V.; 2011. | ||

Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–19. | ||

Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672–676. | ||

Guy W. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976:534–537. | ||

Leatherman SM, Liang MH, Krystal JH, et al; CSP 555 Investigators. Differences in treatment effect among clinical subgroups in a randomized clinical trial of long-acting injectable risperidone and oral antipsychotics in unstable chronic schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(1):13–17. | ||

McDonnell DP, Kryzhanovskaya LA, Zhao F, Detke HC, Feldman PD. Comparison of metabolic changes in patients with schizophrenia during randomized treatment with intramuscular olanzapine long-acting injection versus oral olanzapine. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2011; 26(6):422–433. | ||

Sliwa JK, Fu DJ, Bossie CA, Turkoz I, Alphs L. Body mass index and metabolic parameters in patients with schizophrenia during long-term treatment with paliperidone palmitate. BMC Psychiatry. 2014; 14(1):52. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.