Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 17

Effects of a Multi-Component Psychological Intervention to Cultivate Mental Health in Older Adults

Authors Sarrionandia S , Gorbeña S, Gómez I , Penas P , Macía P , Iraurgi I

Received 31 May 2022

Accepted for publication 26 August 2022

Published 11 October 2022 Volume 2022:17 Pages 1493—1502

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S376894

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Nandu Goswami

Sare Sarrionandia, Susana Gorbeña, Ignacio Gómez, Patricia Penas, Patricia Macía, Ioseba Iraurgi

University of Deusto, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Psychology, Bilbao, Spain

Correspondence: Sare Sarrionandia, Tel +34 944139000 ext 3122, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Psychological interventions to cultivate mental health in older adults are scarce and tend to focus on and use a limited number of activities.

Objective: The aim of this study was to test the effects of an intervention based on Keyes’ concept of positive mental health.

Methods: The intervention was conducted with 24 self-selected participants, while 34 were part of the control group. Positive mental health and distress outcomes were measured at baseline and at the end of the intervention. ANCOVA analysis and effect sizes were calculated.

Results: Results showed that the intervention increased mental health (F= 18.22, p< 0.001, η2= 0.334, d= 1.45, power 0.986) and decreased psychiatric symptomatology in the experimental group versus the control group (F= 7.07, p= 0.011, η2= 0.16, d= 0.87, power= 0.736), which showed no change.

Discussion: Despite study limitations, the intervention effectively promoted older people’s well-being. Future research, should evaluate the long-term effects of the intervention with varied older adult populations.

Keywords: psychological interventions, positive mental health, older adults, effectiveness

Introduction

The conceptualization of aging has undergone significant changes in the past two decades. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined active aging as “the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age”.1 Due to the increase of life expectancy and the improvement of life quality, people over 60 years are rapidly increasing their numbers. Research on aging has pointed out the differences between pathological and non-pathological aging, and has also defined successful aging.2 This process includes, not only preventing physical diseases, but also promoting positive attitudes and life engagement as individuals and as a part of society.3

Some studies remarked how positive psychology can be used to improve this population’s aging conditions.4 In particular, some positive interventions had been applied to old adults and elders. According to Diener & Chan, the interventions targeting later adulthood are now trying to promote personal, physical and psychological strengths, instead of working on pathologies and illnesses.5 Positive interventions have gained much relevance by promoting the importance of well-being. However, most interventions focused on a single activity such as reminiscence, life review, gratitude and meaning6,7 In fact, Sutipan et al reviewed eight studies with elders and found that the reminiscence intervention was the most widely used.8 Our literature review found only three studies that have investigated the effect of a multidimensional intervention. Ho and colleagues developed a multicomponent intervention covering topics such as happiness, gratitude, optimism and meaning, among others, and tested it in a sample of 74 older adults from Hong Kong.9 They found significant decreases in depression and increases in life satisfaction, gratitude and subjective happiness. In addition, Ortega et al tested an intervention that worked on happiness, autobiographical memories, gratitude, forgiveness and humor.10 Their results showed increases in subjective happiness, life satisfaction, purpose in life, and gratitude and decreases in depressive symptoms. Finally, Jiménez et al also developed a multicomponent program with nine sessions that produced changes in happiness but not in positive affect or optimism.11

In a similar vein, most studies have chosen, as outcome variables, specific psychological constructs like life satisfaction, happiness, subjective well-being, positive affect and optimism, and not an overarching construct of well-being. As Araujo et al pointed out in a scoping review of 44 articles, non-used a comprehensive measure of well-being.12 They pointed out the need to ‘develop empirically validated interventions aimed to promote flourishing in older adults’12 (p. 575).

Finally, several voices13,14 have warned about the lack of a unifying conceptual framework in the arena of positive interventions, and the fact that many interventions were designed without a background theory. However, in recent years, some proposals have been advanced. Keyes’15,16 theory of complete mental health seems especially suitable to inform positive interventions. He described positive mental health or flourishing as something different from the mere absence of mental illness, and operationalized it as a syndrome of symptoms of positive feelings and positive functioning. Subjective or emotional well-being (positive emotions and life satisfaction), psychological well-being (self-acceptance, positive relations with others, personal growth, purpose in life, environmental mastery and autonomy) and social well-being (coherence, actualization, integration, acceptance and contribution) are the three components of mental health. Keyes defined flourishing as a state characterized by high levels of well-being, “a state in which an individual feels positive emotion toward life and is functioning well psychologically and socially”16 (p. 294) and its opposite as languishing. His research has tested the theory with ample samples in different countries, including older adults.17 Keyes argues that positive mental health is susceptible of change throughout the life cycle and that programs should be developed to protect and promote health.18–21

In an attempt to remedy this lack of theoretical foundation, Gorbeña et al developed a multi-component intervention based on this construct and results with young adults indicated that the intervention was effective.22 The intervention, described in the next section, is, to the best of our knowledge, unique in that it addresses subjective, psychological and social well-being and avoids a focus on changing maladaptive behavioral patterns as other multi-component interventions do. For instance, Friedman et al focused only in psychological well-being, and used CBT to work on cognitive restructuring.23

In sum, the goal of this study was to test the intervention in a sample of older adults. The first hypothesis stated that participants would improve their scores in positive mental health after the intervention compared to controls. The second hypothesis proposed that participants would reduce their scores in psychological distress after the intervention compared to controls.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited at a medium-size university in the Adult Continuing Education Program. It is a convenience sample of 58 individuals. Ages ranged from 45 to 75 years old (M= 64.3; SD= 6.67), 69% were females, 53% were married, 41% had some chronic health condition, and 5% reported a disability. Twenty-four participants registered in the well-being and personal development workshop, and 18 completed the intervention and the posttest. The control group included 34 participants who enrolled in a course on culture and humanities in the same program; of those, seven cases were lost in the posttest. An analysis of differences at baseline between the two groups in the sociodemographic and health variables showed no statistical significant differences (Age: t= 0.86, p= 0.392, M(SD)Intervention= 65.26(6.93) vs M(SD)Control= 63.71(6.51); Gender: χ2(2)= 0.07, p= 0.796, Female 70.8% vs 67.6%; Civil status: χ2(2)= 1.35, p= 0.246, Married status 62.5% vs 47.1%; Chronic health condition: χ2(2)= 0.01, p= 0.970, 41.7% vs 41.2%; Disability: χ2(2)= 2.23; p= 0.135, 0.0% vs 8.7%).

Instruments

Participants completed, at pre and posttest, five standardized instruments to obtain a measure of subjective, psychological and social well-being, and of psychological distress. Time lapse between measurement times was 10 weeks. A brief description of the instruments follows.

Satisfaction with life scale-SWLS24 adapted to Spanish by Vázquez et al.25 The scale consists of five items with a seven-point response format, from zero “strongly agree” to six “strongly disagree”, and an overall score ranging from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 30 points is obtained. It is a sound and widely used measure; the internal consistency in the Spanish adaptation was 0.88, and the convergent validity was assessed by performing Pearson bivariate correlations, obtaining r=0.44, p<0.01 with a measure of subjective happiness; and r=0.31, p<0.01 with a social support measure. In this study, the alpha was 0.82.

Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) developed by Diener and colleagues26 as a measure of the amount of time positive and negative emotions are experienced in the past four weeks. The scale consists of 12 items, with a response format ranging from one (very rarely or never) to five (very often or always), and an overall score ranging from a minimum of six to a maximum of 30 points is obtained for each of the affect scales. It yields three scores: positive, negative, and balance affect, but only the positive affect score was used in this study. Cronbach Alpha for the positive affect scale was 0.87 in the original study, 0.86 in the Spanish adaptation27 and 0.88 in this study. The convergent validity showed a significant correlation with satisfaction with life (r= 0.711, p< 0.001) and positive affects in the PANAS positive affects scale (r=0.684, p<0.001).27

Psychological Well-Being Scales developed by Ryff28 and adapted to Spanish.29 The scales measure six dimensions of psychological well-being: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. This version consists of 39 items with a 6-point Likert scale response, from zero “strongly agree” to five “strongly disagree”, and an overall score ranging from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 195 points is obtained. The scales are considered a sound measure of positive functioning in the eudaimonic tradition of well-being research.20,30 As an indicator of psychological well-being, the score resulting from the average sum of the items was used. The original scales showed a test-retest reliability between 0.81 and 0.85 and the adaptation showed an internal consistency between 0.68 and 0.83 in the sub scales. The alpha in the present study was 0.90.

Social Well-Being Scales by Keyes.31 This instrument was adapted to Spanish in 2005 by Blanco and Diaz.32 It measures five dimensions of social well-being: integration, acceptance, contribution, coherence and actualization. The scale includes 33 items, with a 5-point response format, from zero “strongly agree” to four “strongly disagree”, and an overall score ranging from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 132 points is obtained. The Spanish version eliminated eight items of the original scale, but given that the adaptation utilized a small non-representative sample, all the items of Keyes’ original scale were included. In the Spanish adaptation, all sub scales showed a negative and significant correlation with the factor of anomia (between −0.18 and −0.38, p<0.01) and a positive and significant correlation with social action (between 0.15 and 0.44, p<0.01). The original scale showed an internal consistency between 0.57 and 0.81 in the sub scales, and the alpha for the total scale in this study was 0.88.

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). It is a short screening instrument for common mental disorders developed by Goldberg and Hillier.33 Participants have to report how often they have experienced a series of symptoms in the last few weeks. The 12 items present a Likert type response format with a range of responses from zero (better than usual) to three (much worse than usual), and an overall score ranging from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 36 points is obtained. The Spanish adaptation34,35 showed an adequate internal consistency with a Cronbach´s alpha of 0.76, and a correlation with the ISRA inventory for anxiety of r=0.57, p<0.001. In this study, the alpha obtained was 0.86.

Procedure

The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study secured the approval of the Board of Research Ethics of the University of Deusto and all participants signed an informed consent, received a numerical code to anonymize the data, and did not obtain any credit for their collaboration. Two facilitators (female and male, one a certified clinical psychologist) simultaneously conducted the intervention with two groups of 12 participants each.

The Personal Development and Well-Being Program22 is an intervention developed after Keyes’ concept of positive mental health and thus it attempts to cultivate subjective, psychological and social well-being. A detailed manual describes the program and the materials used. It includes a section on facilitators’ training and supervision. Facilitators should have a minimum of a master’s level training in psychology and should complete an eight-week experiential training module that requires the completion of all the activities presented in the program. Two-hour supervision session takes place after each session to review the work done and prepare the forthcoming session.

The intervention consists of eight weekly sessions of two hours of duration. Each session presents a different topic using a combination of group or dyadic dialog, brief presentations, audiovisual material, exercises and tests, and testimonies. One third of the sessions were devoted to reviewing the homework assignment of the previous week. Participants received a folder to keep all the materials and a Well-being Notebook to use throughout the experience. A brief outline of the sessions appears in Table 1. Upon completion of the program, all participants completed the posttest measures described.

|

Table 1 Personal Development and Well-Being Program: Summary of Sessions |

Given the mean age of the group, the original program was adapted and the session on future life goals eliminated. This session, based on King’s work,36 asks participants to envision and write about the best possible self in ten years, in different life domains. The activity has been mainly used with young adults and students37 and some authors13 have pointed out uneasiness of participants faced with this challenge and others have underscore the need to validate the exercise with older adults.38 We assumed that this exercise, for people of an average age of 65, might not be adequate and thus precaution and participants’ well-being were favored.

Data Analysis

Scores for subjective, psychological, and social well-being were created from the specific questionnaires of each construct and following the indications of the authors. The variables were transformed into a decimal scale using the following algorithm: ([∑xi – min] * [10/max-min]), being ∑xi the sum of the scores of the items that compose the instruments, and min and max are the minimum and maximum values of the possible range. A higher score expressed a greater presence of the assessed construct. For example, a score of “100” on the Ryff scale would be equivalent to a score of “5.12” on the decimal scale: ([100–0] * [10/195-0] = 100 * 0.0512 = 5.12).

Following Keyes,15 subjective well-being was the mean average of the Positive Affect subscale of the SPANE instrument, and the Life Satisfaction measure. Psychological well-being was the sum of the items of Ryff’s instrument. Social well-being resulted from the addition of the items of Keyes’ scale. The positive mental health variable was created calculating the average sum of the three well-being indicators. The same procedure was used to obtain the mental distress variable using the GHQ-12.

To describe data, means (M) and standard deviations (SD) were used for the scale variables, and percentages (%) for the nominal variables. The normality of the distributions was verified with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the spherical assumption of the variance-covariance matrix was checked with the Mauchly’s W-test. t test for independent samples was used to analyze differences in base line between the intervention and control group, and to determine differences between present and lost cases. Subsequently, t test for paired samples for the pre post-test comparisons was conducted, with robust corrections in case the assumption of homoscedasticity was not met. To estimate effect sizes of mean differences, Cohen’s d coefficient was calculated, as suggested by Lakens.39 A commonly used interpretation is to refer to effect sizes as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8) based on benchmarks suggested by Cohen.40 In order to compare proportions, Chi squares were used.

Finally, the effects of the design utilized (comparison of two groups with pre-post-facto measures) were jointly analyzed using ANCOVA and calculating intergroup, intragroup and interaction effects (F-test), taking as an estimate of the effect size the eta square coefficients (η2). Sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, chronic health condition and disability) have been introduced into the ANCOVA models as covariates in order to control the effect over the treatment outcomes. The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Preliminary analyses aimed at checking whether there were differences between cases included in the study and participants lost to follow-up, both in the intervention and control groups (Table 2). The comparison showed no statistical significant differences in any of the five outcome variables, a finding that allowed for the elimination of one possible source of bias in the study.

|

Table 2 Comparisons at Base Line of Present and Lost Cases: Outcome Variables on a Decimal Scale |

Table 3 summarizes descriptive results of both groups at base line, and the contrast of means and effect sizes of the differences. There are no statistical significant differences in social well-being (t= −1.52, p= 0.134). However, differences were found for subjective well-being, psychological well-being, positive mental health, and the GHQ, with effect sizes ranging from moderately high (d= 0.66 and 0.69 for the GHQ and psychological well-being, respectively) to high (d= 0.94 and 0.98 for positive mental health and subjective well-being). Base line scores in the control group were higher for positive mental health and lower for psychological distress, an outcome expected due to the self-selected nature of the recruitment procedure.

|

Table 3 Comparisons in Base Line of Intervention and Control Groups: Outcome Variables on a Decimal Scale |

Table 4 presents change scores (MDif) between post-test and base line for each group. In general, scores show a change in the direction of an improvement, compared with base line, but none is significant in the control group, indicating stability in well-being, positive mental health and psychological distress. However, differences are significant in the intervention group in all variables, with notable (d= 0.83 for positive mental health) and moderate to high (d values between 0.41 and 0.74) effect sizes. It should be noted that the GHQ shows a reduction in the intervention group (MDif= −0.76, p= 0.004, d= 0.60) compared with a non-significant increase in the control group (MDif= 0.17, p= 0.471, d= 0.14).

|

Table 4 Pre Post Test Change in Intervention and Control Groups: Mean Differences and Effect Sizes |

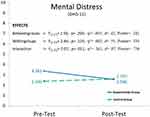

Subsequently, a repeated measures analysis of variance was conducted, as depicted in Figure 1 and Figure 2, along with the statistical tests. Positive mental health showed more improvement in the intervention group than in the control group, with statistically significant (p< 0.001) interaction effects (η2= 0.334, d= 1.45, power 0.986). A similar effect can be observed in psychological well-being and social well-being, even though the difference is small. The strongest effect of the intervention can be seen in subjective well-being, where all the comparison effects are significant (inter group: F= 5.72, p= 0.022, η2= 0.14, d= 0.81; intra group: F= 10.28, p= 0.003, η2= 0.198, d= 0.99; interaction: F= 13.82, p< 0.001, η2= 0.283, d= 1.26, power= 0.951). These results indicated increased improvement in the intervention group, even though scores are still below the control group.

|

Figure 1 Evolution of outcomes in well-being indicators and positive mental health. Blue continuous line: experimental group. Green dotted line: control group. |

|

Figure 2 Evolution of outcomes in mental distress. Blue continuous line: experimental group. Green dotted line: control group. |

As it regards the GHQ (Figure 2), both groups had scores below 3.5, indicating a low presence of symptoms of emotional distress. There are not inter or intra group differences, but there is an interaction effect (F= 7.07, p= 0.011, η2= 0.16, d= 0.87, power= 0.736), showing a bigger deceleration slope of distress in the intervention group at post-test.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to test the effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention, based on the construct of positive mental health with older adults. This framework considered positive mental health as a state composed by three different types of well-being (subjective, psychological and social), and it also considered mental distress as a factor that hinders mental health.15,16

The outcomes of the study show an important improvement in all self-reported measures for the experimental group: subjective, psychological and social well-being outcomes were higher after the intervention, and the level of mental distress reported was lower. Those differences were not found in control group, whose mental health level remained the same after eight weeks. The results for subjective and psychological well-being are consistent with previous interventions in mental health with older adults.9,10,41

The reduction of mental distress symptoms observed is also in accordance with some previous studies that tested the reduction of depression, anxiety or stress in elder population after a positive psychological intervention.23,42 The main effects sized found for mental health and reduction of mental distress were medium and big effects.

A remarkable contribution of the intervention is to include and evaluate social well-being as part of positive mental health in older adults. The results on the post-test show that the experimental group increased significantly its reported social well-being, while control group suffered no variation. This outcome measure was also used in Friedman et al23 with some significant improvements that are in line with the results of this study. However, they only evaluated the subscales of social integration and social contribution, which are only two of the five Keyes’ scales used in the current study.

Although these preliminary results suggest that the intervention designed could be a resource to promote mental health in older adults, some consideration must be taken into account. As far as this is the first application to this age group, some issues should be considered. The session concerning future-self and life goals was omitted because of the characteristic of the group. Instead, a session about reminiscence exercises or life-review could be included, following Sutipan et al’s8 suggestion about the effect of those activities in this age group. Similarly, other validated activities could be included. For instance, act of kindness can affect the three dimensions of well-being, given that it has been proved that it produces increases in subjective well-being and might have an impact in some dimensions of psychological well-being (ie self-acceptance, positive relationships and purpose in life). Cultivating kindness can also foster social well-being and could impact in social contribution and social integration.43,44

Other limitations in this study include the differences that control and experimental groups showed at baseline. Even if there were not differences in sociodemographic variables and social well-being, the control group reported higher scores in subjective and psychological well-being. This could be because participants on the experimental group were self-selected. Besides, this self-selection could also affect experimental group’s expectations about the intervention and its success. The motivation to improve that the group had may have affected their improvement in the post-test, as suggested by Sin and Lyubomirsky.45 Future research should include a larger randomized sample, 6-month follow up measures, and the analysis and control of other variables that might be affecting group’s improvement.

To sum up, research2,46 has pointed that interventions with old adults and elders should not only encompass the avoidance of mental and physical disease, but also promote positive human functioning and growth in later life. In this context, positive psychological interventions seem to be a useful tool,4 though much work is still ahead to empirically validate the interventions and elucidate the processes and mechanism of change involved. The proposal by Gorbeña et al22 merits further work and adaptations to foster the well-being of older adults.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure

The Authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest.

References

1. World Health Organization. Active ageing: a policy framework; 2002. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67215.

2. Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist. 1997;37(4):433–440. doi:10.1093/geront/37.4.433

3. Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging 2.0: conceptual expansions for the 21st century. Gerontol B Psychol Sci Sco. 2015;70(4):593–596. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv025

4. Ranzijn R. Towards a positive psychology of ageing: potentials and barriers. Aust Psychol. 2002;37(2):79–85. doi:10.1080/00050060210001706716

5. Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2011;3(1):1–43. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x

6. Avia MD, Martínez-Martí ML, Rey-Abad M, Má R, Carrasco I. Evaluación de un programa de revisión de vida positivo en dos muestras de personas mayores [Evaluation of a positive life review programme in two samples of older people]. Rev Psicol Soc. 2012;27(2):141–156. doi:10.1174/021347412800337852

7. Davis MC. Life Review Therapy as an intervention to manage depression and enhance life satisfaction in individuals with right hemisphere cerebral vascular accidents. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2004;25(5):503–515. doi:10.1080/01612840490443455

8. Sutipan P, Intarakamhang U, Macaskill A. The impact of positive psychological interventions on well-being in healthy elderly people. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(1):269–291. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9711-z

9. Ho HCY, Yeung DY, Kwok SYCL. Development and evaluation of the positive psychology intervention for older adults. J Posit Psychol. 2014;9(3):187–197. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.888577

10. Ortega AR, Ramírez E, Chamorro A. Una intervención para aumentar el bienestar de los mayores [An intervention to increase the well-being of older people]. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2015;5(1):23–33. doi:10.1989/ejihpe.v1i1.87

11. Jiménez MG, Izal M, Montorio I. Programa para la mejora del bienestar de las personas mayores. Estudio piloto basado en la psicología positiva [Programme to improve the well-being of the elderly. Pilot study based on positive psychology]. Sum Psicol. 2016;23(1):51–59. doi:10.1016/j.sumpsi.2016.03.001

12. Araujo L, Ribeiro O, Paúl C. Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in old age through positive psychology studies: a scoping review. An Psicol. 2017;33(3):568–577. doi:10.6018/analesps.33.2.265621

13. Parks AC, Biswas-Diener R. Positive interventions: past, present, and future. In: Kashdan TB, Ciarrochi J, editors. Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Positive Psychology: The Seven Foundations of Well-Being. Oakland: Context Press; 2013:140–165.

14. Wong PTP, Roy S. Critique of positive psychology and positive interventions. In: Brown NJ, Lomas T, Eiroa-Orosa FJ, editors. The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Positive Psychology. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2018:142–160.

15. Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):207–222. doi:10.2307/3090197

16. Keyes CLM. Complete mental health: an agenda for the 21st century. In: Keyes CLM, Haidt J, editors. Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2003:293–312.

17. Snowden M, Dhingra S, Keyes C, Anderson L. Changes in mental well-being in the transition to late life: findings from MIDUS I and II. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2385–2388. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.193391

18. Grzywacz J, Keyes CLM. Toward health promotion: physical and social behaviors in complete health. Am J Health Behav. 2004;28(2):99–111. doi:10.5993/ajhb.28.2.1

19. Keyes CLM. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing. Am Psychol. 2007;62(2):95–108. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95

20. Keyes CLM. Promotion and protection of positive mental health: towards complete mental health in human development. In: David SA, Boniwell I, Conley Ayers A, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Happiness. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013:915–925. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199557257.001.0001

21. Keyes CLM, Dhingra S, Simoes E. Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental Illness. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2366–2371. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.192245

22. Gorbeña S, Govillard L, Gómez I, et al. Design and evaluation of a positive intervention to cultivate mental health: preliminary findings. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2021;34(7):1–10. doi:10.1186/s41155-021-00172-1

23. Friedman EM, Ruini C, Foy CR, Jaros L, Sampson H, Ryff CD. Lighten UP! A community based group intervention to promote psychological well-being in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(2):199–205. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1093605

24. Diener E, Emmons R, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

25. Vázquez C, Duque A, Hervás G. Satisfaction with life scale in a representative sample of Spanish adults: validation and normative data. Span J Psychol. 2013;16(E82):1–15. doi:10.1017/sjp.2013.82

26. Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, et al. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;97(2):143–156. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

27. Espejo B, Checa I, Perales-Puchalt J, Lisón JF. Validation and measurement invariance of the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) in a Spanish general sample. Int J Environ ResPublic Health. 2020;17(22):1–15. doi:10.3390/ijerph1722835993

28. Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(6):1069–1081. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

29. Díaz D, Rodríguez-Carvajal R, Blanco A, et al. Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff [Spanish adaptation of the pychological well-being scales (PWBS)]. Psicothema. 2006;18(3):572–577.

30. McDowell I. Measures of self-perceived well-being. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(1):69–79. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.07.002

31. Keyes CLM. Social well-being. Soc Psychol Q. 1998;61(2):121–140. doi:10.2307/2787065

32. Blanco A, Díaz D. El bienestar social: su concepto y medición [Social Well-being: theoretical structure and measurement]. Psicothema. 2005;17(4):582–589.

33. Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9(1):139–145. doi:10.1017/s0033291700021644

34. Lobo A, Pérez-Echeverría MJ, Artal J. Validity of the scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) in a Spanish population. Psychol Med. 1986;16(1):135–140. doi:10.1017/S0033291700002579

35. Sánchez-López MP, The DV. 12-Item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): reliability, external validity and factor structure in the Spanish population. Psicothema. 2008;20(4):839–843.

36. King LA. The health benefits of writing about life goals. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2001;27(7):798–807. doi:10.1177/0146167201277003

37. Loveday P, Lovell GP, Jones CM. The best possible selves intervention: a review of the literature to evaluate efficacy and guide future research. J Happiness Stud. 2018;19(2):607–628. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9824-z

38. Meevissen YMC, Peters ML, Albets HJ. Become more optimistic by imagining a best possible self: effects of a two-week intervention. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011;42(3):371–378. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.012

39. Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. 2013;4:1–12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

40. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences.

41. Friedman EM, Ruini C, Foy CR, Jaros L, Love G, Ryff CD. Lighten UP! A community-based group intervention to promote eudaimonic well-being in older adults: a multi-site replication with 6 months follow-up. Clin Gerontol. 2019;42(4):387–397. doi:10.1080/07317115.2019.1574944

42. Durgante H, Dell’Aglio DD. Multicomponent positive psychology intervention for health promotion of Brazilian retirees: a quasi-experimental study. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2019;32(6):1–14. doi:10.1186/s41155-019-0119-2

43. Buchanan K, Bardi A. Acts of kindness and acts of novelty affect life satisfaction. J Soc Psychol. 2010;150(3):235–237. doi:10.1080/00224540903365554

44. Fredickson B, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM. Open hearts build lives: positive emotions induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(5):1045–1062. doi:10.1037/a0013262

45. Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well‐being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice‐friendly meta‐analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):467–487. doi:10.1002/jclp.20593

46. Diehl M, Smyer MA, Mehrotra CM. Optimizing aging: a call for a new narrative. Am Psychol. 2020;75(4):577–589. doi:10.1037/amp0000598

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.