Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Effect of English Learning Motivation on Academic Performance Among English Majors in China: The Moderating Role of Certain Personality Traits

Received 23 March 2023

Accepted for publication 20 May 2023

Published 14 June 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2187—2199

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S407486

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Yongjun Zhang,1– 3 Huijun Wang1,4

1School of Foreign Languages, Anhui Jianzhu University, Hefei, Anhui, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, People’s Republic of China; 3Institute of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics, Anhui Jianzhu University, Hefei, Anhui, People’s Republic of China; 4School of Education, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Correspondence: Huijun Wang, Email [email protected]

Background: Previous studies have explored the interrelationship among learning motivation, personality traits, and academic performance, but little is known about the role of personality traits in the relationship between foreign language learners’ motivation and academic performance, especially in the Chinese setting, where English is taken as a compulsory course in universities.

Purpose: This study aimed to fill the gap by investigating the relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance among English majors in China and identifying the moderating role of certain personality traits, sequentially providing some implications for improving college English teaching strategies in China.

Methods: English majors (N=273) from different types of universities in China were recruited to complete the revised version of the English learning motivation scale and big five personality traits scales via an online survey platform. Descriptive statistics, correlation analyses and hierarchical regression analyses were performed to explore the relationships among the three variables.

Results: Results demonstrated that English learning motivation and openness both significantly influenced academic performance and significant interaction effects were found between English learning motivation and agreeableness. Specifically, agreeableness partially moderated the relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance, and English learning motivation had a positive effect on academic performance only for learners with lower levels of agreeableness.

Conclusion: These findings not only addressed the gap of the moderating role of personality traits in the motivation-performance relationship but also extended our knowledge of the roles of English learning motivation and certain personality traits in English learning within the context of China, where English is taken as a foreign language, thus providing practical suggestions for college English teachers and researchers in China to improve students academic performance.

Keywords: English learning motivation, personality traits, academic performance, agreeableness, moderation effect

Introduction

Being a global language, English is more widely used than any other languages.1 In China, a developing country where English is regarded as an essential instrument for economic growth, modernization, and globalization,2 learning English well is generally acknowledged as an effective way to promote cross-cultural communication. Motivation is recognized as a key determinant in foreign language learning as it has an impact on how well language learners achieve.3,4 Previously, the motivation-achievement relationship has been investigated and studies have demonstrated the positive effect of motivation on students’ achievement.5,6 Furthermore, it was discovered that students with high motivation believe language learning could extend their future educational and career opportunities in the rapidly-changed globalization times.7 These studies would suggest that motivation can influence the process and the result of language learning.

Moving beyond this, Poropat assumed that students with different personality features have different learning behaviors and outcomes, and students’ personality traits could be predictive of their academic success.8 Based on the framework of the Big Five model put forward by Costa and McCrae,9 many studies have revealed the impact of personality traits on academic achievement. It was indicated that neuroticism negatively predicted foreign language achievement,10 while agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and extraversion positively predicted academic performance.11–13 Obviously, different personality traits have different effects on students’ learning outcomes.

Although existing studies have found the association between learning motivation and academic performance or the relation between certain personality traits and learning outcomes, research involving the complex relationship among the three variables is relatively sparse. Specifically, it was found that motivation played either a moderating role,6,11 or a mediating role in the personality-performance relationship,14 and personality traits only played a mediating role in the motivation-performance relationship.15 In addition, relevant research on the interrelationship among the three variables has been conducted within European and North American settings,16,17 but the role of certain personality traits in the relation between learning motivation and academic performance remains unknown in Asian settings such as China, where English is taken as a foreign language. However, it has been validated that there are strong relationships between certain personality traits and performance motivation,18,19 together with the well-documented effect of motivation on academic achievement which is further examined in a recent study,20 so it is likely that certain personality traits might moderate the relationship between motivation and academic performance. As described above, the objective of the current study is to examine the relationships between English learning motivation, personality traits, and academic performance, and disentangle the moderating role of certain personality traits in the motivation-performance relationship among English majors in China.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

English Learning Motivation

According to Bomia et al, motivation in the field of education is identified as students’ willingness, need, desire, and obligation to participate in and succeed in the learning process.21 Generally speaking, it is the driving force based on emotions and achievement-related goals behind an individual’s behaviors.22 Therefore, English learning motivation can be viewed as a determining factor in terms of English learning achievement. Typically, students with high motivation levels are capable of responding to the learning environment, seeking out and making use of the opportunities to learn English, and leading to effective learning outcomes, which in turn promotes motivation. Oxford and Shearin also claimed that motivation is crucial in foreign language learning in that it provides the primary drive for learners to initiate and persist in mastering the target language.23 It also contributes to facilitating learners’ needs and obtaining learning objectives. Thus, concentrating on students’ English learning motivation can be beneficial for interpreting their success in learning English.

In the field of foreign language acquisition, there are two fundamental theoretical frameworks for learning motivation. One was proposed by Gardner and Lambert who concluded two basic types of motivation: instrumental motivation and integrative motivation.24 The former reflects learners’ potential specific purposes for learning a foreign language, such as gaining a better job, and the latter on the other hand, demonstrates a sincere interest in foreign cultures and a strong desire to interact with the target language community. The other framework was put forward by Brown who categorized learners’ orientation of motivation as intrinsic and extrinsic.25 Intrinsic individuals are motivated for the sake of enjoyment, while extrinsic individuals are motivated by achieving rewards or goals beyond an activity. Although the instrumental/integrative and intrinsic/extrinsic motivation scales have been examined in contexts that are different from China where English is taken as a foreign language (EFL),26 these may not be the optimal instruments for measuring EFL learners’ motivation in the Chinese context. Therefore, an instrument27 of English learning motivation for Chinese learners developed by Gao et al could be more appropriate for the current study. In Gao et al’s study, seven types of English learning motivation were summarized and defined: intrinsic interest is reflected in an individual’s appreciation or fondness for the target language and its culture; immediate achievement relates to a requirement for satisfactory results in exams; learning situation is linked to the learning environment, such as the quality of textbooks, teachers, and the learning group; going abroad is associated with the pursuit of studying or working overseas; learners with social responsibility are oriented to take English learning as a way to fulfill social expectations and strengthen national power; individual development refers to the purpose of increasing personal ability and social status for future development; information medium focuses on utilizing English as a medium to obtain information and learn other subjects.27 All these orientations contribute to the success of foreign language learning, and they are not mutually exclusive, which means learners generally have a mixture of motivational orientations in most learning situations.

The Influence of English Learning Motivation on Academic Performance

Although lines of research on the associations between English learning motivation and academic performance has been conducted,11,28,29 the results seem to be inconsistent across studies. A positive relationship between learning motivation and English achievement was found among Chinese university students11 and Iranian high school students29 respectively. Moreover, Mendoza et al also reported an association between students’ autonomous motivation and high achievement in English language learning.20 In contrast, Binalet and Guerra demonstrated that motivation is not highly correlated with English achievement in a selected group of Philippines university students and stated that the success or failure to acquire English is not related to learners’ English learning motivation,28 and a non-significant relationship between the two variables in senior high school samples was also discovered in Ghana.30 So this study hereby further validates the relationship between the two variables, especially among English majors in the context of China. Based on the aforementioned reasoning, the first hypothesis is that English learning motivation has a positive impact on academic performance among English majors in China (H1).

Personality Traits

Personality is defined as “an individual’s characteristic patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior, together with the psychological mechanisms - hidden or not - behind those patterns”.31 It describes stable patterns of an individual’s behavior lasting for long periods of time.32 In the long term, it can influence an individual’s options and help determine the boundaries of success and life fulfillment. Being a well-accepted theory, the Big Five model9 classified individual personalities into five types: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. As stated by Komarraju et al, neuroticism is featured with emotional instability, impulse control, and anxiety; extraversion is characterized by a high degree of sociability, assertiveness, and talkativeness; openness is associated with strong intellectual curiosity, divergent thinking, and a preference for novelty and variety; agreeableness encompasses qualities of altruism, friendliness, modesty, generosity, and cooperation; conscientiousness features self-discipline and persistence.33 The Big Five personality traits provide a comprehensive summary of people’s emotions and their interpersonal, experiential, attitudinal, and motivational traits.34 It should be noted that the five trait scores are relatively independent, so a person’s scoring on one trait reveals virtually nothing about their scoring on the other traits.35

The Influence of Personality Traits on Academic Performance

A study conducted by Vedel et al observed significant group differences in the Big Five personality traits in different academic majors and it was found that arts/humanities students such as English majors score higher on agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness.36 Therefore, the current study specifically examines the influences of the three personality traits on academic performance among English majors in China, and further explores their moderating effects on the relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance.

Agreeable students are normally helpful, cooperative, trusting, and sympathetic toward others. Empirical studies found that those agreeable students are more perseverant and have a stronger desire for self-improvement,37 and they tend to be motivated to acquire knowledge intrinsically.26 Although there are studies reporting no associations between agreeableness and academic performance,6,38 relevant research has revealed that agreeableness is a positive predictor of academic achievement.33 Additionally, Shirdel and Naeini also reported a positive relationship between agreeableness and English achievement in a sample of undergraduate English learners.13 Therefore, this study hypothesizes that agreeableness has a positive impact on academic performance among English majors in China (H2).

Neurotic students are prone to experience self-doubt and negative emotions in day-to-day situations and regularly feel anxiety in the face of exams and pressures.38 These effects would naturally make them exhibit an undirected learning style and have trouble identifying and processing the important materials, which ultimately leads to poor academic performance.37 Furthermore, students with these personality characteristics are more likely to avoid many aspects of their learning and consider education just as a means to an end rather than an activity driven by intrinsic motivation.37 Given that neuroticism is related to low emotional stability and high anxiety, its negative effect on students’ overall grade point average (GPA) has been yielded.15,39 A similar negative influence of neuroticism on EFL achievement was also discovered in a sample of 164 university students in Taiwan, China by Kao and Craigie.10 Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that neuroticism has a negative impact on academic performance among English majors in China (H3).

Individuals high in openness tend to think independently and unconventionally. Openness also seems to facilitate cognitive exploration,40 which could increase the likelihood of experiencing learning situations.41 Students with this personality trait enjoy exposure to new ideas, favor engaging in the learning experience, and thus may benefit from discussion and interactive learning.37 It is also believed that open individuals prefer a deep approach in learning which concentrates on the meaning of the learning materials.42 In the field of foreign language learning, existing studies have detected a positive relationship between openness and foreign language achievement in participants across a wide range of ages.12,43 Hence, the fourth hypothesis is that openness has a positive impact on academic performance among English majors in China (H4).

The Moderating Role of Personality Traits Between English Learning Motivation and Academic Performance

Although motivation can directly influence academic performance, its effect on performance may be different due to learners’ different personality traits, and some empirical studies have shed some light on personality traits’ potential moderating roles underlying the relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance.

Individuals with agreeableness are generally kind, considerate, and altruistic. Since some studies have reported that agreeableness is positively associated with academic achievement among university undergraduates,13,33 it seems that agreeableness is also likely to be positively related to approval and affiliation motivation.37 As for learners with a high level of agreeableness, they will be more inclined to be intrinsically motivated to gain knowledge and accomplish things, making them feel obligated to attend classes, and this could help them achieve satisfactory results in their studies.26 On the contrary, it was revealed that disagreeable students have difficulty in perceiving any reward for their behaviors and thereafter lack motivation from time to time.26 As such, those students can hardly make progress, let alone fulfill academic goals. Thus, this study hypothesizes that agreeableness has a moderating effect between English learning motivation and academic performance among English majors in China (H5).

By contrast, people who are neurotic tend to experience unstable emotions and feel unable to handle challenges and setbacks. Some studies have verified its negative impact on foreign language achievement.10,15 Komarraju and Karau found that compared to students with a low level of neuroticism, those high on neuroticism demonstrated the features of avoidance, one of the academic motivations, which incorporates anxiety, discouragement, and withdrawal during the learning process.37 These disadvantageous feelings and behaviors weaken students’ motivation and make them fail to process the important learning materials effectively, which potentially affects neurotic students’ school performance negatively. Consequently, this research proposes the following hypothesis: neuroticism has a moderating effect between English learning motivation and academic performance among English majors in China (H6).

Students with openness appear to think independently and often enjoy discussion and interactive learning.37 Studies have detected a positive association between openness and foreign language achievement.12,43 A study conducted by Bakke et al also believed that open learners are capable of profiting from the weekly resources in their study environment, and therefore foster enthusiasm and motivation in their studies.44 It was indicated that students who are high in openness have a strong desire to gain a deep understanding of learning materials, and thus perform better than their peers with low levels of openness.14 Conversely, students with a low level of openness are less likely to be intrinsically motivated to know and to experience stimulation,26 and thus engage few in intellectual activities, which leads to poor learning outcomes. Therefore, the last hypothesis of this study is that openness has a moderating effect between English learning motivation and academic performance among English majors in China (H7).

Based on the series of hypotheses above, the theoretical model of the current study is shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical model. |

Methods

Participants and Procedure

This survey was conducted from November 2021 to March 2022 in seven different types of Chinese universities located in different cities. A random sampling method was adopted to select participants for the questionnaire survey, and convenience sampling was also used as a supplement to expand the samples. After obtaining informed consent from the office of educational administration, an online questionnaire hosted by Wenjuanxing (https://www.wjx.cn/) was distributed to the targeted students, who were English majors in their junior or senior years at the time of the survey. All the participants gave electronic informed consent to participate in the study and they were informed about the research purpose, the possible time needed, and the confidentiality of responses. Initially, 303 students voluntarily filled out the questionnaire, but after eliminating invalid responses such as blankness and inconsistency, the final sample was comprised of 273 English majors (39 males and 234 females).

Measures

English Learning Motivation

The English learning motivation was measured by the scale catered to Chinese college students.45 The scale included 21 items (eg, “I study English in order to let the world get to know China”) and had a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”. Higher scores denoted higher motivation for English learning. The measure has demonstrated good reliability and validity among Chinese undergraduates.45,46 In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.830.

Big Five Personality

The personality traits were measured by a brief Chinese version of the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI),47 which was compiled by Costa and McCrae.48 The scale is a 60-item questionnaire consisting of five subscales: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Each of the five traits is comprised of 12 items, such as “I seldom feel blue”. It was scored on a five-point scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”. This scale has been used in the Chinese population with sound reliability and validity.49,50 In the current study, three subscales of agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness were selected for the above-mentioned reasons. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.663 for agreeableness, 0.821 for neuroticism, and 0.713 for openness.

Academic Performance

Test for English Majors-Band 4 (TEM-4) is an exam for English majors administrated by the National Advisory Committee for Foreign Language Teaching (NACFLT) on behalf of the Higher Education Department, Ministry of Education, China. It is demonstrated that TEM tests are reasonably reliable and valid in the context of China.51 In this study, the students’ exam scores in TEM-4 were adopted as their academic performance. Therefore, all the respondents were asked to provide their TEM-4 test scores in numerical form.

Control Variables

Previous studies have shown that grade and gender would affect students’ English performance.6,52 Accordingly, the two demographic characteristics variables above were statistically controlled in all subsequent analyses.

Common Methods Bias Test

Common method variance, which also refers to general method bias or same source bias, may occur when using self-report measures from the same sample during a survey.53 It describes the value of spurious correlation among variables that can be generated by measuring variables with the same method (eg, survey). Harman’s one-factor test is utilized to examine the common method bias. Generally, it exists if there is a single factor or a general factor that accounts for most of the variance. In the present study, after all the items were loaded on a single unrotated factor, the analysis indicated that the first principal factor explained only 13.13% of the variance, which was well below the value of 50%.54 Therefore, common method variance did not exist in the present study.

Statistical Analysis

All the analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 23.0. The bivariate correlations were used to establish the relationships between the study variables. The hierarchical regression analysis was then utilized to explore the influence of each personality trait on academic performance. After that, another hierarchical multiple regression procedure was conducted to test the moderating role of the three personality traits.55 English learning motivation and the three personality traits were also centered on the means to reduce multicollinearity effects.56 Simple slopes analysis was conducted to further specify the significant interaction patterns.57

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were performed for all variables in the current study (see Table 1). As shown in the table, English learning motivation is significantly positively correlated with academic performance (r = 0.266, p < 0.01) and openness (r = 0.351, p < 0.01). Openness is positively correlated with academic performance (r = 0.137, p < 0.05), while neuroticism is significantly negatively related to agreeableness (r = −0.191, p < 0.01). Among control variables, gender is significantly positively correlated with agreeableness (r = 0.242, p < 0.01) and openness (r = 0.160, p < 0.01), while negatively correlated with neuroticism (r = −0.177, p < 0.01).

|

Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of the Variables (N = 273) |

Hypotheses Testing

Table 2 includes results for the regression analysis used to estimate the prediction of agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness on academic performance respectively, with grade and gender as control variables. Of the three personality traits, only openness was a significant positive predictor of academic performance (β = 0.133, p = 0.031). Therefore, hypothesis 4 was supported while hypothesis 2 and hypothesis 3 were not verified.

|

Table 2 Effects of Personality Traits on Academic Performance |

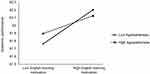

Furthermore, another hierarchical regression analysis demonstrating the moderating results was shown in Table 3. In model 2, it can be seen that English learning motivation has a significant and positive impact on English academic performance (β = 0.263, p < 0.01). Therefore, hypothesis 1 was supported. In models 3 to 5, English learning motivation and each moderating variable (agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness) were entered respectively to validate their effects on academic performance. Models 6 to 8 introduced the product term of mean-centered English learning motivation with each personality trait on the basis of models 3 to 5. For agreeableness, compared with model 3, model 6 improved significantly (ΔF = 3.970, p < 0.05), ΔR2 was 0.014, and the product term between English learning motivation and agreeableness on academic performance yielded a significant equation (β = −0.118, p = 0.047), indicating agreeableness and English learning motivation interacted to influence academic performance. Following Aiken and West,57 we plotted an interaction graph at +/− 1 SD from the mean of agreeableness (see Figure 2). The interaction graph showed that, compared with English majors with high agreeableness, the regression slope between English learning motivation and academic performance was greater for English majors with low agreeableness. Specifically, in the case of low agreeableness, English learning motivation has a greater positive impact on academic performance (β = 0.313, p < 0.001). However, in the case of high agreeableness, the relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance is non-significant (β = 0.124, p > 0.05). The results partly verified hypothesis 5. Regarding neuroticism, compared with model 4, model 7 did not improve, and the interaction term between English learning motivation and neuroticism was not significant (β = −0.093, p = 0.135), indicating that neuroticism did not have any moderating effect on the relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance, so hypothesis 6 was not supported. With respect to openness, compared with model 5, model 8 also did not improve, and the product term between English learning motivation and openness was insignificant (β = 0.101, p = 0.091), so hypothesis 7 was also rejected.

|

Table 3 Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis |

|

Figure 2 The moderating effect of agreeableness between English learning motivation and academic performance. |

Discussion

Through an empirical analysis of the data of 273 English majors in China, this study examined the complex relationships among English learning motivation, three personality traits, and academic achievement by employing some scales especially applicable to Chinese undergraduates. Several key findings can be listed as follows:

First, in line with the findings of existing studies,5,6 it was shown that English majors in China who have higher English learning motivation were more likely to have better academic performance. For those with high motivation, they generally have a strong drive to work diligently and energetically, stay focused on academic goals, outperform other students, and exceed high standards of excellence.58 These features could drive them to perform better academically than their peers who lack English learning motivation. Nevertheless, as can be seen in the result, there is a relatively low relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance. This may well suggest that other influential factors may mediate or moderate the relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance.

Second, in the personality-achievement relationship, it was indicated that openness has a positive effect on academic performance, which accorded with the existing literature.6,12 The finding to a large extent also matches the characteristics of students with openness. English majors who are curious and imaginative seem to be willing to spend more time dealing with new problems and receiving new information so as to grasp more learning opportunities,41 and this potentially helps them do well in academic performance. Besides, it was also highlighted that both neuroticism and agreeableness were found to have no significant influence on academic performance. This finding supported the work of Zhou,6 which concluded that neuroticism and agreeableness do not predict Chinese primary students’ academic performance. Nevertheless, it was out of accord with the results from two other studies conducted in different culture settings,13,15 which both indicated neuroticism and agreeableness are predictors for undergraduates’ academic achievement. The inconsistent results may arise from different teaching models in different cultures. As mentioned before, one of the features of neuroticism is associated with anxiety problems, especially when the learners are facing exams. Chinese students, however, have rich exam experiences in the Chinese educational context,59 and this may relieve those neurotic students from anxiety. Hence, a non-significant relationship between neuroticism and academic achievement was found among English majors in China. According to the meta-analysis conducted by Poropat, it was reported that the higher the educational level was, the weaker relationship between agreeableness and academic achievement existed.8 Concretely, the correlation coefficient declined from 0.30 at the primary education level to 0.06 at the tertiary education level. And this could well explain why the insignificant association existed among these college students in the current study.

Finally, by analyzing the moderating effects of different personality traits, the result revealed that in China, where English is reckoned as a foreign language, agreeableness could exert a buffering effect on academic performance, such that English learning motivation was relevant only for low agreeable students and not for their high agreeable counterparts. This suggests that at a low level of agreeableness, the positive impact of English learning motivation on academic achievement would be strengthened. The features of agreeableness can shed some light on interpreting the moderating effect. It is acknowledged that high agreeable individuals tend to be highly cooperative and supportive, have the willingness to work or study effectively with their peers, and are inclined to have low levels of ambition at the same time. Particularly in the academic field, it was shown that agreeableness was negatively related to an achieving style emphasizing high grades,37 which indicated that English majors who have a lower level of agreeableness are likely to have stronger ambition in their academic outcomes. In addition, it was found that agreeableness was negatively correlated to competing among undergraduates, indicating low agreeable students want to do better than their peers with high agreeableness,37 thus they may prefer to increase engagement in learning and thereby outperform their peers. The relatively higher levels of ambition, competition, and engagement among students with low agreeableness relate closely to the features of English learning motivation, such as immediate achievement, which is characterized by the desire to gain satisfactory results or high scores in exams.27 Therefore, low agreeableness can enhance the effect of English learning motivation on academic achievement among English majors in China generally. Apart from the moderating effect of agreeableness, it was noteworthy that the p-value of the interaction term between openness and academic performance was 0.091, which was marginally significant. It is likely that the influence of English learning motivation on academic performance may be stronger for students with higher levels of openness. It is demonstrated that high open students display a strong intellectual curiosity about the study resources and trigger their intrinsic motivation in the process of learning English,15 and can achieve relatively better learning outcomes. In contrast, students with a lower level of openness may have less enthusiasm and passion for discussions or interactions involved in or after class, and this eventually results in their relatively poor performance in the long run. Finally, as for the role of neuroticism in the relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance, no moderation effect was found. This result may suggest that the effect of English motivation on academic performance would not be influenced by the trait of neuroticism, and it is likely due to the fact that neuroticism has no effect on students’ engagement and motivation in English learning, which was also corroborated by Komarraju and Karau.37

Theoretical Contributions

This study examined the influence of English learning motivation on academic performance under the condition of controlling for grade and gender in the Chinese EFL context. This result lends support to the findings of studies on the positive relationship between English learning motivation and academic performance.11,29 In the meantime, it further validates the influence of English learning motivation on academic performance in the Chinese EFL context. In addition, this study introduced three different personality traits into the theoretical framework and found that openness positively predicted academic performance. This also accords with prior empirical studies revealing that openness is positively related to foreign language achievement.12,43 The difference is that the present study shows its positive impact on English achievement and clearly suggests that Chinese EFL learners who are intellectually curious and enjoy variety and novelty can produce positive learning outcomes.

This study further enriches motivation-personality-achievement-related theory by highlighting the indispensable role of certain personality traits between learning motivation and academic achievement. Specifically, this study disentangles the moderating role of agreeableness in the motivation-achievement relationship. Notably, the finding of the moderating role of agreeableness is somewhat surprising. Foreign language learning is generally viewed as a process that involves active communication and cooperation with others, so the qualities of cooperation and kindness that agreeable students possess can benefit their learning process, increase their motivation and assist them to outperform their classmates. Our finding, however, reveals that a low level of agreeableness can strengthen the influence of English learning motivation on academic performance, whereas a high level of agreeableness does not influence the effect of English learning motivation on academic performance. This unexpected finding provided us with a new perspective to reflect upon the role of agreeableness in academic achievement among English majors in China.

Practical Contributions

Since English learning motivation significantly influences students’ academic performance in the Chinese EFL context, college English teachers should increase their efforts to motivate students in order to make them achieve higher outcomes possibly by employing appropriate and innovative teaching approaches. Despite the ability to communicate is crucial in second language learning,60 studies showed that Chinese university students are unwilling to communicate in English in EFL classrooms.61,62 This is mainly due to the Chinese traditional values of harmony and humbleness, the habit of staying silent developed in previous school experiences, personal and psychological reasons for shyness and fears of losing face, and large class sizes. Accordingly, English teachers are supposed to learn more about knowledge on educational psychology so as to help students break those social and psychological barriers, and move around in the classroom or stand in the middle in the case of a large class size. An option for a motivated pedagogical method could be the flipped classroom, which emphasizes an expansion of the curriculum, rather than a mere rearrangement of activities.63 It may allow students to increase engagement in studies, cultivate critical thinking frequently, and improve learning outcomes effectively. According to Wang and Zhou’s review of the application of flipped classrooms in Chinese college English teaching, flipped teaching is confirmed to allow students to be more expressive in English conversational activities and keep motivating them to practice oral English.64

Moreover, educators should be aware of the effects of certain personality traits on students’ learning outcomes. Therefore, it makes sense to utilize appropriate teaching strategies for students with different personality characteristics. For example, now that low agreeableness enhances the positive effects of English learning motivation on academic performance, it is suggested that teachers should leave enough space for students with a low level of agreeableness to fully develop their engagement in autonomous learning rather than force them to work in group activities in in-class teaching. As for students with openness, for instance, teaching strategies involving interesting cultural exposures can be devised to nurture students’ qualities of openness.11

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although it is common that there are always far more female students than males in the foreign language departments in China, it should be noted that the conclusions drawn from this study may not be completely generalized to the whole group of English learners in China due to the uneven male-to-female ratio. Besides, participants’ English achievement data were collected in a self-reported way, as such, it may include some errors due to memory constraints or inflated estimates,65 which might cause the marginally significant result of the moderating effect of openness. Therefore, future research could attempt to obtain objective data from college official records with students’ permission.

In conclusion, this study reported some significant relationships between English learning motivation, personality traits, and academic performance. In detail, it demonstrated that both English learning motivation and the trait of openness can positively predict English majors’ academic performance when grade and gender were set as control variables. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that agreeableness can weaken the positive predictive effect of English learning motivation on academic performance. The current work is an important step in understanding the fundamental role of English learning motivation and certain personality traits in explaining English majors’ academic performance in China, and meanwhile it sheds some light on teaching strategies for foreign language teachers in the context of China. Future research is also encouraged to take other potential variables such as learners’ emotional intelligence into consideration when interpreting or predicting foreign language achievement.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Science and Technology Ethics Committee of Anhui Jianzhu University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the General Project of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Education Department in Anhui Province (SK2019A0661), the Research Project of Industry-University-Institute Cooperation (HYB20210164) and the College Innovation Training Program in Anhui Jianzhu University (2021xj311).

Disclosure

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

1. Rao PS. The role of English as a global language. Res J English. 2019;4(1):65–79.

2. Gao YH, Zhao Y, Cheng Y, Zhou Y. Relationship between English learning motivation types and self-identity changes among Chinese students. TESOL Q. 2007;41(1):133–155. doi:10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00043.x

3. Cocca M, Cocca A. Affective variables and motivation as predictors of proficiency in English as a foreign language. J Effic Responsib Educ Sci. 2019;12(3):75–83. doi:10.7160/eriesj.2019.120302

4. Gardner RC. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation. London: Edward Arnold; 1985.

5. Chalak A, Kassaian Z. Motivation and attitudes of Iranian undergraduate EFL students towards learning English. GEMA Online J Lang Stud. 2010;10(2):37–56.

6. Zhou MM. Moderating effect of self-determination in the relationship between big five personality and academic performance. Pers Individ Differ. 2015;86:385–389. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.005

7. Kitjaroonchai N. Motivation toward English language learning of students in secondary and high schools in education service area office 4, Saraburi province, Thailand. Int J Lang Linguist. 2012;1(1):22–23. doi:10.11648/j.ijll.20130101.14

8. Poropat AE. A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(2):322–338. doi:10.1037/a0014996

9. Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992.

10. Kao PC, Craigie P. Effects of English usage on Facebook and personality traits on achievement of students learning English as a foreign language. Soc Behav Pers. 2014;42(1):17–24. doi:10.2224/sbp.2014.42.1.17

11. Cao C, Meng Q. Exploring personality traits as predictors of English achievement and global competence among Chinese university students: English learning motivation as the moderator. Learn Individ Differ. 2020;77:101814. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2019.101814

12. Rosander P, Bäckström M, Stenberg G. Personality traits and general intelligence as predictors of academic performance: a structural equation modeling approach. Learn Individ Differ. 2011;21(5):590–596. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2011.04.004

13. Shirdel T, Naeini MASB. The relationship between the big five personality traits, crystallized intelligence, and foreign language achievement. N Am J Psychol. 2018;20(3):519–528.

14. Hazrati-Viari A, Rad AT, Torabi SS. The effect of personality traits on academic performance: the mediating role of academic motivation. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;32:367–371. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.055

15. Komarraju M, Karau SJ, Schmeck RR. Role of the big five personality traits in predicting college students’ academic motivation and achievement. Learn Individ Differ. 2009;19(1):47–52. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.07.001

16. De Feyter T, Caers R, Vigna C, Berings D. Unraveling the impact of the big five personality traits on academic performance: the moderating and mediating effects of self-efficacy and academic motivation. Learn Individ Differ. 2012;22(4):439–448. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2012.03.013

17. Di Domenico SI, Fournier MA. Able, ready, and willing: examining the additive and interactive effects of intelligence, conscientiousness, and autonomous motivation on undergraduate academic performance. Learn Individ Differ. 2015;40:156–162. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2015.03.016

18. Judge TA, Ilies R. Relationship of personality to performance motivation: a meta-analytic review. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(4):797. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.87.4.797

19. Fuertes AMDC, Blanco Fernández J, García Mata MDLÁ, Rebaque Gómez A, Pascual RG. Relationship between personality and academic motivation in education degrees students. Educ Sci. 2020;10(11):327. doi:10.3390/educsci10110327

20. Mendoza NB, Yan Z, King RB. Domain-specific motivation and self-assessment practice as mechanisms linking perceived need-supportive teaching to student achievement. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2022;1–24. doi:10.1007/s10212-022-00620-1

21. Bomia L, Beluzo L, Demeester D, Elander K, Johnson M, Sheldon B. The Impact of Teaching Strategies on Intrinsic Motivation (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 418 925). Champaign, IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education; 1997.

22. Rabideau ST. Effects of achievement motivation on behavior; 2005. Available from: http://www.personalityresearch.org/papers/rabideau.html.

23. Oxford R, Shearin J. Language learning motivation: expanding the theoretical framework. Mod Lang J. 1994;78(1):12–28. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02011.x

24. Gardner RC, Lambert WE. Attitudes and Motivation in Second Language Learning. Rowley, Mass: Newbury House; 1972.

25. Brown DH. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching.

26. Clark MH, Schroth CA. Examining relationships between academic motivation and personality among college students. Learn Individ Differ. 2010;20(1):19–24. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2009.10.002

27. Gao YH, Zhao Y, Cheng Y, Zhou Y. Motivation types of Chinese university undergraduates. Mod Foreign Lang. 2003;26(1):28–38.

28. Binalet CB, Guerra JM. A study on the relationship between motivation and language learning achievement among tertiary students. Int J Appl Linguist English Lit. 2014;3(5):251–260. doi:10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.3n.5p.251

29. Dashtizadeh P, Farvardin MT. The relationship between language learning motivation and foreign language achievement as mediated by perfectionism: the case of high school EFL learners. J Lang Cult Educ. 2016;4(3):86–102. doi:10.1515/jolace-2016-0027

30. Emmanuel AO, Adom EA, Josephine B, Solomon FK. Achievement motivation, academic self-concept and academic achievement among high school students. Eur J Res Reflection Educ Sci. 2014;2(2):24–37.

31. Funder DC. The Personality Puzzle. NY: Norton; 1997.

32. Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: stability and change. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:453–484. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913

33. Komarraju M, Karau SJ, Schmeck RR, Avdic A. The big five personality traits, learning styles, and academic achievement. Pers Individ Differ. 2011;51(4):472–477. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.019

34. Chamorro-Premuzic T, Furnham A. Personality predicts academic performance: evidence from two longitudinal university samples. J Res Pers. 2003;37(4):319–338. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00578-0

35. Diener E, Lucas RE. Personality traits. In: Biswas-Diener R, Diener E, editors. General Psychology: Required Reading. Champaign, IL: DEF Publishers; 2019:278–295.

36. Vedel A, Thomsen DK, Larsen L. Personality, academic majors and performance: revealing complex patterns. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;85:69–76. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.030

37. Komarraju M, Karau SJ. The relationship between the big five personality traits and academic motivation. Pers Individ Differ. 2005;39:557–567. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.013

38. Kappe R, van der Flier H. Using multiple and specific criteria to assess the predictive validity of the big five personality factors on academic performance. J Res Pers. 2010;44(1):142–145. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.11.002

39. Laidra K, Pullmann H, Allik J. Personality and intelligence as predictors of academic achievement: a cross-sectional study from elementary to secondary school. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;42(3):441–451. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.08.001

40. DeYoung CG, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Gray JR, Eastman M, Grigorenko EL. Sources of cognitive exploration: genetic variation in the prefrontal dopamine system predicts openness/intellect. J Res Pers. 2011;45(4):364–371. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2011.04.002

41. Ziegler M, Danay E, Heene M, Asendorpf J, Bühner M. Openness, fluid intelligence, and crystallized intelligence: toward an integrative model. J Res Pers. 2012;46(2):173–183. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.002

42. Zhang LF. Does the big five predict learning approaches? Pers Individ Dif. 2003;34(8):1431–1446. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00125-3

43. Rizvanović N. Motivation and personality in language aptitude. In: Reiterer SM, editor. Exploring Language Aptitude: Views from Psychology, the Language Sciences, and Cognitive Neuroscience. Springer; 2018:101–116. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-91917-1_6

44. Bakker AB, Sanz Vergel AI, Kuntze J. Student engagement and performance: a weekly diary study on the role of openness. Motiv Emot. 2015;39(1):49–62. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9422-5

45. Xu HC, Gao YH. The development of English learning motivation and learners’ self-identities: a structural equation modeling analysis of longitudinal data from five universities. Foreign Lang Learn Theory Pract. 2011;3:63–70.

46. Liu L, Gao YH. The development of English learning motivation and learners’ self-identities: a sample report of English majors in their fourth undergraduate year at a comprehensive university in China. Foreign Lang Their Teach. 2012;2:32–35. doi:10.13458/j.cnki.flatt.000480

47. Huang XT. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. Shanghai: East China Normal University Press; 2003.

48. Costa PT, McCrae RR. The NEO Personality Inventory Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1985.

49. Du QN, Zhu SK, Zeng LM, Deng YY, Du YH, Wu NN. The links between personality traits and depression among university students during the epidemic of COVID 19: the mediating role of resilience. Psychologies. 2021;16(13):23–25. doi:10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2021.13.009

50. Hou J, Tian S, Sun XY, et al. The influence of big five personality on the use of social networking sites: the mediating role of narcissism. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2020;28(6):1202–1208. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.06.026

51. Jin Y, Fan J. Test for English majors (TEM) in China. Lang Test. 2011;28(4):589–596. doi:10.1177/0265532211414852

52. Gottardo A, Yan B, Siegel LS, Wade-Woolley L. Factors related to English reading performance in children with Chinese as a first language: more evidence of cross-language transfer of phonological processing. J Educ Psychol. 2001;93(3):530–542. doi:10.1037//0022-0663.93.3.530

53. Podsakoff PM, Todor WD. Relationships between leader reward and punishment behavior and group processes and productivity. J Manage. 1985;11(1):55–73. doi:10.1177/014920638501100106

54. Podsakoff PM, Organ DW. Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manage. 1986;12(4):531–544. doi:10.1177/014920638601200408

55. Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences.

56. Jaccard J, Turrisi R, Wan CK. Interaction Effects in Multiple Regression. Newbury Park: Sage; 1990.

57. Aiken LS, West S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991.

58. Awan R, Noureen G, Naz A. A study of relationship between achievement motivation, self-concept, and achievement in English and mathematics at secondary level. Int Educ Stud. 2011;4:72–79. doi:10.5539/ies.v4n3p72

59. Yin H, Han J, Lu G. Chinese tertiary teachers’ goal orientations for teaching and teaching approaches: the mediation of teacher engagement. Teach High Educ. 2017;22(7):766–784. doi:10.1080/13562517.2017.1301905

60. Kayi H. Teaching speaking: activities to promote speaking in a second language. Int TESL J. 2006;12(11):1–6.

61. Malik MA, Sang G, Li Q. Chinese university students’ lack of oral involvements in the classroom: identifying and breaking the barriers. J Res Reflect Educ. 2017;11(2):162–177.

62. Peng JE, Woodrow L. Willingness to communicate in English: a model in the Chinese EFL classroom context. Lang Learn. 2010;60(4):834–876. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00576.x

63. Bishop J, Verleger MA. The flipped classroom: a survey of the research.

64. Wang Y, Zhou T. A review of application on flipped classroom in Chinese college English teaching.

65. Gramzow RH, Elliot AJ, Asher E, McGregor HA. Self-evaluation bias and academic performance: some ways and some reasons why. J Res Pers. 2003;37:41–61. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00535-4

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.