Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Does My Humor Touch You? Effect of Leader Self-Deprecating Humour on Employee Silence: The Mediating Role of Leader-Member Exchange

Authors An J , Di H, Yang Z, Yao M

Received 21 March 2023

Accepted for publication 2 May 2023

Published 4 May 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1677—1689

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S411800

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Jiaji An,1 He Di,2 Zixuan Yang,3 Meifang Yao2

1School of Finance, Jilin University of Finance and Economics, Changchun, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Business and Management, Jilin University, Changchun, People’s Republic of China; 3Shenzhen Finance Institute, School of Management and Economics, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: He Di, School of Business and Management, Jilin University, 2699 Qianjin Ave, Changchun, 130012, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Silence is a typical negative behaviour exhibited by employees when they are faced with tension and stress and is influenced by a number of factors. Leaders have an important influence on employees’ emotions and behaviour, but the research is not yet clear enough. In this paper, we focus on the research frontier of self-deprecating humour of leaders, aiming to analyse its effect on employee silence and discuss the mechanism of the role of leader-member exchange (LMX) in it, based on social exchange theory.

Methods: We conducted a regression analysis and bootstrap test for mediating effects based on 2531 data from 151 financial institutions in mainland China. A simple random sampling was taken of the target population to ensure an unbiased sample. Using Harman’s single-factor test to check the data for common method bias. Regression analysis and Bootstrap test were used to analyze the correlation between variables and mediating effect models.

Findings: (a) Leader self-deprecating humour significantly reduces employee silence and effectively improves the quality of LMX; (b) There is a significant negative relationship between LMX and employee silence; (c) LMX plays a mediating role in the process of self-deprecating humour influencing employee silence and this mediating effect is complete; (d) Affective exchange between leaders and employees appears to be an essential factor in reducing stress from leaders and reducing employee silence.

Originality/Value: We attempt to open the black box of the mechanism of action between leader self-deprecating humour and employee silence, enrich and expand the application of social exchange theory to negative employee behavior, and provide new theoretical knowledge and empirical evidence from developing countries.

Practical Implications: The results of the study indicated that self-deprecating humor of leaders can significantly inhibit employee silence through high levels of LMX. Moreover, the mediating role played by LMX was complete. Therefore, organizations should not only focus on the role of leadership humor, but also to achieve mutual respect and trust between leaders and subordinates, and an emotional exchange that goes beyond economic relationships.

Keywords: leader self-deprecating humour, employee silence, leader-member exchange, mediating effect

Introduction

Technological advances, the competitive environment and the increasing demands of work have become real challenges for employees; very often they have to take on more responsibility, maintain a high work pace and face constant change. All these factors have a negative impact on mental health and lead to a decrease in the potential of human capital. These negative effects often lead employees to withdrawing behaviour, of which silent behaviour is a typical one.1 Employee silence is a negative and detrimental behavior to the organization.2 The advice given by employees who are familiar with the organisation’s operational processes should not be ignored. Employees who identify discrepancies between plans and reality in their operations, make sensible suggestions and give feedback will provide decision makers with first-hand data. But if employees choose to remain silent, it can be costly to the organisation and damage the proper functioning of business activities. For example, Lehman Brothers, once the fourth largest investment bank in the US, went bankrupt after 158 years of operation due to the subprime mortgage crisis, and one of the key reasons for this was the failure of internal staff to provide timely feedback to the firm’s decision makers on issues identified.3 There are of course other examples including the Enron financial scandal.4 It has been noted that many times employees choose to keep or conceal their thoughts and exhibit silent behaviour even though they are clearly aware of these specific issues.5 Hassan et al6 found a rising trend in employee silence within organisations and found that up to 85% of employees did not speak up about issues in the organisation. This is due to the fact that employees’ public suggestions put great psychological pressure on employees and increase the likelihood of damaging relationships between superiors and subordinates and authoritative leadership.

Humour is a common phenomenon in the workplace and has a unique impact on interpersonal relationships in organisations and on the mood of individuals at work. Leader humour is often cited as one of the key elements of a successful leader, as it is often impressive in public and has many spillover effects. In a survey of 329 CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, 97% of CEOs agreed that humour is important in business and that CEOs should develop their sense of humour more often.7 In recent years, leader humour has attracted the attention of management scholars as an emerging area of leadership research. Several studies have found that leader humour contributes to employee performance,8 emotional commitment,9 organisational citizenship behaviour10 and innovative behaviour,11 among others. Although existing research has explored and found that leader humour plays an important role in promoting positive employee behaviours, there is still less focus on negative employee behaviours.12 Particularly in today’s increasingly uncertain and competitive business environment, studying such negative behaviours within organisations, such as employee silence, has important implications for human resource management in companies. Similarly, research on self-deprecating leader humour is still in its infancy compared to other types of humour, and further research is needed to explore the results and mechanisms of its effects in organisations.

Social exchange theory believes that avoiding harm is a basic principle of human behaviour and that rational people should try to avoid competing in conflicts of interest and instead achieve win-win or multi-win through mutual social exchange.13 From the existing literature, leader-member exchange (LMX) based on social exchange theory is an important factor in revealing the spillover effects of leadership behaviour.14,15 The way leaders behave influences the quality of their relationship with their subordinates, and the quality of the relationship between the two acts on employees’ ability to perceive the constructive situation, which in turn reduces silent behaviour.

Social exchange theory gives new explanatory power to LMX as a mediating variable. This study used simple random sampling method to randomly sample the target population and obtained sufficient survey data. The unbiasedness and reliability of these data were ensured with the help of Harman’s single-factor test and validated factor analysis. We introduced LMX as a mediating variable into the model of leader self-deprecating humour and employee silence to empirically investigate the relationship and theoretical mechanisms at play between the three variables. The gap between this study and the existing literature is that, firstly, we respond to theoretical concerns about negative employee behaviour. While existing research has explored and found that leader humour has an important role in promoting positive employee behaviours, there is still less attention paid to negative employee behaviours. Secondly, we have identified a number of new organisational factors and the mechanisms by which they work together. Currently, there is limited literature that includes leader self-deprecating humour, leader-member exchange and employee silence under the same framework, and our study could enrich the existing set of theoretical variables. Thirdly, we have identified a number of new factors affecting employee mental health and new ways to enhance mental health, and these findings may shed light on the human resource management practices of organisations.

Theoretical Analysis and Hypotheses

The Relationship Between Leader Self-Deprecating Humour and Employee Silence

Employee silence is when employees who would otherwise be able to make suggestions and initiatives based on their work experience and skills to improve and refine the work processes of their organisation or departmental unit, choose to retain their views for multiple reasons.16 Harlos17 defines silence as when employees have the ability to improve current organisational performance but retain behavioural, cognitive or emotional evaluations of, for example, the organisational environment. The silent behavior of employees is often a negative impact from emotional tension at work.18 On the one hand, employees are often under social pressure to give work advice or interact with colleagues in formal or informal settings.19 On the other hand, employees’ opinions can often be misconstrued by leaders as a challenge to their own competence or position of authority, especially in organizations that have a more rigid culture.20 Employee silence can be detrimental to the organization, such as the act of hiding knowledge and avoiding talking about identified problems such as reduced productivity, operational risks, and deviations from target plans.21 Kumar et al22 argued that the psychological expectation of rational people to “prioritise loss” means that the impact of resource loss is far more important than resource gain, and that its impact is faster and longer lasting. Silent behavior is appearing with increasing frequency as a symptom of employee psychological subhealth, stress and burnout, and deserves attention.23 Li and Xing24 argued that employee silence is mainly caused by managers and is rooted in employees’ fear that speaking up will lead to their leaders’ anger, which is detrimental to their career development, and is the main motivation for employee silence.

Leader humour seems to be a very effective informal stress-reliever within organisations.25 Humour in organisations as a form of greeting refers to the sender sharing an event to the receiver with the intention of entertaining others and the receiver feeling that this is intentional.26 Pundt and Herrmann27 defined leader humour as a communicative behaviour where the leader intends to entertain a particular subordinate, or team, through acts such as sharing funny things or team. Martin et al28 proposed a 2×2 model of humour styles, which divided the dimensions of affectionate, aggressive, self-empowering and self-deprecating humour according to the object and nature of the humour used. The first three dimensions are more direct humour behaviours, while self-deprecating humour is relatively indirect. Self-deprecating humour has been less studied and is more challenging.29 Self-deprecating humour in leadership is a manifestation of a leader making benign jokes or witty comments about their own shortcomings and mistakes that are non-hostile, supportive and induce positive emotions in the team.30 This humour shows that leaders dare to gently make fun of their own mistakes and shortcomings, without taking themselves too seriously, but maintaining a sense of self-acceptance and tolerance for others.31 Hoption et al32 distinguished the self-deprecating humor and deprecating humor. They believed that self-deprecating humor is an important method that speakers use in conversation to level with each other and become of “one mind”. Compared to deprecating humor, self-deprecating humor is rather friendly than offensive.

This paper argues that self-deprecating humour can positively influence employees and reduce their silent behaviour for the following reasons: firstly, self-deprecating humour is a unique kind of positive humour that is friendly, tolerant and affirming of self and others. In the process of interacting with subordinates, self-deprecating humour can demonstrate the leader’s approachability and bring subordinates closer to each other, making employees more willing to share their ideas and new perspectives with the leader and to actively communicate with him/her.33 This kind of humour gives employees a sense of trust, which encourages them to question, think independently and actively voice their suggestions, thus effectively reducing the motivation for silence and contributing to organisational democracy.34 Secondly, self-deprecating humour by leaders conveys honesty, frankness and humility in looking at themselves, and a willingness to make themselves potentially vulnerable by pointing out their weaknesses and revealing the truth.29 Employees’ non-silent behaviours can often be challenging, and self-deprecating humour from leaders allows leaders to be more open and patient in their interactions with subordinates, breaking down established organisational norms and sending a benign and violable signal.35 Self-deprecating humour can create a relaxed, inclusive and open atmosphere in the organisation, allowing employees to think in a relaxed environment, which can increase their courage and confidence to actively contribute, thus reducing their silent behaviour.

Based on the above theoretical analysis, this study proposes hypothesis 1.

H1: Leader self-deprecating humour has a significant negative effect on employees’ silence.

The Mediating Role of Leader-Member Exchange

Social exchange theory suggests that because leaders have limited time and energy, they invest different amounts and quality of resources in dealing with different employees, thus creating varying levels of exchange quality in their interactions with employees.36 The leader-member exchange (LMX) concept, developed from social exchange theory, characterises the quality of exchange relationships between leaders and their subordinates.37 In a low-quality exchange relationship, the leader-member relationship is limited to an economic exchange as defined by the labour contract; in a high-quality exchange relationship, the leader-member relationship is characterised by mutual respect and trust, going beyond the economic exchange to an emotional exchange.38 High-quality LMX is characterised by bilateralism, reciprocity and trust, and can lead to interpersonal relationships of mutual respect and appreciation between subordinates and superiors, while low-quality LMX is more about economic exchange between subordinates and superiors.39 According to social exchange theory, the formation of high quality LMX relationships requires continuous positive interactions between leaders and subordinates.40 It has been shown that LMX is an important mediating mechanism through which leadership style influences employee behaviour.41 We suggest that leader self-deprecating humour, as a positive leadership style, can have a significant impact on employee silence through LMX.

Firstly, leader self-deprecating humour can lead to high quality LMX. Cooper26 proposed a relational process model and suggested that when leaders use affectionate humour, the positive emotional experience for employees not only makes the leader more attractive, but also deepens the emotional exchange between them. A shared response to a point of laughter implies similar interests between the leader and the subordinate, and the perception of being “like minded” brings them closer together, reducing the distance due to hierarchical differences.42 As a result, positive interactions between leaders and subordinates can develop into high-quality LMX.43 In addition, leader self-deprecating humour is emotionally reinforcing and helps to break down interpersonal barriers created by formal hierarchies and positions of power in the organisation, helping to alleviate status differences between subordinates and superiors, bringing them closer together, increasing their emotional intimacy, and forming high quality subordinate exchange relationships.44 Accordingly, we propose research hypothesis 2.

H2: Leader self-deprecating humour has a significant positive effect on leader-member exchange.

Secondly, LMX is effective in reducing employee silence. LMX is one of the most important influences on employee motivation.45 In a high-quality relationship, employees receive more resources and emotional support from their leaders, and in return, they are more likely to give back to the organisation the resources they have, including advice.46 At the same time, high-quality LMX provides employees with a sense of psychological security and emotional commitment, enhances their sense of belonging and self-efficacy, reduces their concerns about uncertainty and risk in the process of positive suggestion, increases their initiative, and reduces silent behaviour. Accordingly, we propose hypothesis 3.

H3: LMX plays a mediating role in the process by which leader self-deprecating humour acts on employee silence.

Based on the above assumptions, the hypothesized mediation model was drawn in this study, as shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 The hypothesized mediation model. |

Methods

Data Sources

This paper uses the Wenjuanxing, which is the most popular questionnaire platform in China, relying on university alumni associations and graduates in finance to conduct online research on questionnaire data. A total of 151 financial institutions in China were selected for the research, including banks, trusts, security traders, funds, insurance companies, financial leasing companies, finance companies and internet finance companies, and etc. The sample distribution is roughly the same as the structure of China’s financial industry. To reduce the impact of data bias, simple random sampling was used to randomly sample 52,713 employees of the research population. This study collected data from employees and leaders at two time points. At time point 1, employees were asked to fill in the basic personal information and leader self-deprecating humour awareness questionnaire. At time point 2 (one month later), employees who completed the questionnaire at time point 1 were asked to complete the perceptions of LMX and silent behaviour questionnaire. This was to avoid indiscriminate completion, missing data and unsuccessful matching.47 After eight months of research, a total of 3777 questionnaires were distributed and 2531 questionnaires were validly returned. In the final valid sample set, the gender of the employees was predominantly male, with 1605 (63.4%); the age was predominantly 26–35 years old, with 1010 (39.9%); and the education level was predominantly undergraduate, with 1288 (50.9%).

Data Processing

We screened and processed the questionnaire data. Firstly, the Interquartile Range (IQR) method was used to mark outliers. We used 1.5 times the IQR as a criterion, specifying that points exceeding the upper quartile + 1.5 times the IQR distance, or the lower quartile - 1.5 times the IQR distance, were outliers. Outliers were treated by placing them as vacant, for a total of 168. Secondly, we processed the missing values, identifying null values, spaces and the string “None”. Following Royston,48 these missing values were statistically filled, converted to triple standard deviations of values and new variables were generated.

Measurement Tools and Reliability Analysis

The independent variable (leader self-deprecating humour) was measured using a well-established questionnaire developed by Cooper et al10 and adapted around “self-deprecating”, containing 3 items including My leader uses self-deprecating humour to make colleagues laugh and etc., with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.871. Leader self-deprecating humour was recorded as SDH. LMX, as the mediating variable was measured using a questionnaire developed by Liden et al49 with 9 items, including “I am willing to do things for the leader that are beyond my job responsibilities”, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.824. The dependent variable (employee silence) was measured using the scale developed by Tangirala et al50 which contains five questions, with a typical question such as “I do not express an opinion on the phenomenon that affects my work efficiency in the organisation”, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.807. Employee silence is recorded as ES. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each of the above variables is greater than 0.8, indicating that the data obtained from the questionnaire is reliable and meets the measurement requirements. Previous research has shown that demographic characteristics often have an impact on individual behaviour,51,52 so this paper set gender, age and educational attainment as control variable. The main variables were scored on a Likert 5-point scale, with the exception of leader self-deprecating humour, which was scored on a Likert 6-point scale. The data processing and statistical computing software used in this study was SPSS 27.0, and the definitions and measures of each of these variables are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Definition of Variables |

Validity of Constructs

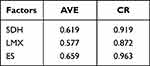

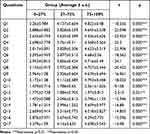

In order to examine the validity of the data constructs, a convergent validity analysis and a discriminant validity analysis were conducted. Firstly, for convergent validity, we used the validating factor analysis function of SPSS to conduct Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Construct Reliability (CR) tests on the three factors consisting of 17 items. The results are shown in Table 2. The results show that the AVE values for all three factors are greater than 0.5, which indicates that the internal consistency of the structure of the factors is high, with good construct reliability and high convergent validity. In addition, we also found that the CR values for each factor were greater than 0.7, which implies that all topics in the variable explained the variable consistently and that the internal convergent validity of the factors was high.53 Secondly, in terms of discriminant validity, this study was analysed using the more mainstream 27/73 quantile method and the results are shown in Table 3. The results of the discriminant validity analysis showed that the p-value for the differentiation of the three main variables in this study was 0.000*** which showed significance at the level and rejected the null hypothesis, indicating that the scale items were designed with a high degree of differentiation and a more reasonable design. The main research variables and data of this paper passed the validity analysis. To further test the data for common method bias (CMB), we analyzed the amount of variance explained by the first common factor by using Harman’s single-factor test. The results showed that the percent of equations explained by the first common factor is 34.64%. This value is less than 50%, and according to Podsakoff et al54 we confirmed that the data is free from CMB.

|

Table 2 Convergent Validity |

|

Table 3 Discriminant Validity |

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

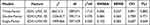

As the variables involved in the study were all filled in by employees on their evaluations, the discriminant validity of the variables needed to be examined before conducting subsequent analyses. We examined the discriminant validity of the variables for leader self-deprecating humour, leader-member exchange, and employee silence using confirmatory factor analysis, and the results are shown in Table 4. It can be seen that the three-factor model was the best fit (χ2 /df = 1.710, RMSEA = 0.046, SRMR = 0.037, CFI = 0.891) compared to the other models. Therefore, the variables discussed in this paper have relatively good discriminant validity between them.

|

Table 4 Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results |

Descriptive Statistics and Tests for Autocorrelation of Variables

Table 5 presents the means, standard deviations and correlation coefficients for SDH, LMX, ES and each of the control variables. According to Table 5, LMH was significantly negatively correlated with ES (r = −0.432, p < 0.01), which provided initial support for subsequent hypothesis testing. The results of the correlation analysis indicated that employees’ age may influence their silent behaviour, which needs to be verified in the subsequent main regression model. In addition, there were no significant correlations between the control, independent and mediating variables, demonstrating that there was no autocorrelation between the variables and no measurement bias.

|

Table 5 Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Variables |

Analysis of Main and Mediating Effects

In terms of testing for mediating effects, this study adopted the Bootstrapping algorithm for 1000 replicate sample draws.55 The results are shown in Table 6 and Table 7. To test for main effects, the control variables and SDH were entered simultaneously into a regression equation with ES as the dependent variable. According to model 2, it is evident that leader self-deprecating humour has a significant negative effect on employee silence (γ = −0.255, p < 0.01) and the hypothesis H1 is supported by the data. This is similar to the findings of Lingard,56 Lanfranco.57 This suggests that the better the humour displayed by the team leader, the more employees tend to voice their opinions rather than remain silent. Model 1 was developed to examine the relationship between SDH and LMX (the mediating variable), and we entered both the control variables and SDH into the regression equation with LMX as the dependent variable. According to Model 1, it can be seen that SDH significantly and positively affects LMX (γ = 0.536, p < 0.01). The hypothesis H2 of this paper was also tested. Currently, few scholars have studied the correlation between leadership self-deprecating humour and leader-member exchange. However, Pundt and Venz,27 Tremblay and Gibson58 tested the positive impact of SDH from similar concepts such as organisational affective commitment. In terms of LMX and employee silence, we produce empirical results (Model 3) that show a significant negative correlation between the two. At this point, LMX negatively affects ES (γ = −0.498, p < 0.01), while the negative effect of SDH on ES is no longer significant (γ = −0.318, p > 0.05).

|

Table 6 Results of Multi-Layer Linear Model Analysis |

|

Table 7 Bootstrap Test |

To examine the mediating effect, we used the bootstrapping method and entered the control variables, SDH and LMX, into the regression equation with the dependent variable of ES at the same time. The results of the mediating effect analysis (Table 7) showed that the mediating variables played a full mediating role. While LMX negatively influenced ES (γ = −0.498, p < 0.01), the negative effect of SDH on ES was no longer significant (γ = −0.318, p > 0.05). Firstly, the 95% BootCI for a*b is (−0.187 ~ −0.347) excluding the number 0, which indicates that the mediating effect is significant. Secondly, in model 2, the negative effect of SDH on ES is significant. However, after the inclusion of the mediating variable, this effect changed from significant in model 2 to insignificant according to model 3. The correlation between the independent variable and the dependent variable changed from significant to insignificant due to the inclusion of mediating variable. This indicates that the mediating variable plays a full mediating role.59 In addition, a*b has a mediating effect value of −0.267 and a*b/c has a value greater than 100% and the same sign as c’, which also proves that LMX plays a full mediating role.60 Our hypothesis H3 was approved. Furthermore, we found that the age variable in employee personal traits was significantly and positively related to employees’ silent behaviour (Model 2 and Model 3 in Table 6). The correlation coefficients between employees’ age and their silent behavior were all positive with 95% confidence intervals. This suggests that employees become increasingly silent in the workplace as they age. This is consistent with some existing research findings as follows. On the one hand, employees’ creativity and motivation tend to diminish with age, and older employees may have developed their own set of working and acting styles over the long years of their careers. They are more inclined to stick to the rules and adapt to existing work habits and therefore do not express their opinions as much.61,62 On the other hand, older employees are more familiar with the work and social rules of the workplace and are less likely to make socially pressured suggestions to their leaders in formal situations.63

Conclusion and Discussion

Conclusion

This paper explores the relationship between leader self-deprecating humour, leader-member exchange and employee silence based on social exchange theory and proposes corresponding hypotheses. Based on a study of 2531 employees in Chinese financial institutions, we conducted an empirical test and analysed the mediating effects using the bootstrap method. It was found that (1) the results of our empirical study showed that leader self-deprecating humor and employee silence are significantly and negatively related which means that leader self-deprecating humour significantly reduces employee silence. This may be due to the fact that self-deprecating humour is passed down and influences subordinates, facilitating interpersonal interactions within the team.64 Moreover, this humour creates a harmonious and democratic communication atmosphere in the team, which means that employees’ suggestions are more likely to be taken on board and employees are less inclined to remain silent.65,66 (2) In all models, there was a significant positive correlation between leader self-deprecating humour and LMX. Therefore, we believe that leader self-deprecating humour is effective in enhancing leader-member exchange. A study by Liao et al67 concluded that positive humor by leaders can effectively help employees break the constraints of social adjustment, which in turn enhances the intensity of emotional exchange between leaders and employees. In addition, this paper constructs a theoretical model of the mediating role of leader-member exchange. The empirical results validate our new findings: (3) The correlation between LMX and employee silence at the 95% confidence interval was negative. There is a significant negative relationship between LMX and employee silence which is consistent with the study of Khassawneh and Elrehail.68 High-quality LMX can bring employees a sense of psychological security and emotional commitment, enhance their sense of belonging and self-efficacy, reduce their worries about uncertainty and risks in the process of active voice, increase their initiative, and thus reduce silent behavior.69 (4) With the help of bootstrap tests, we found that leader-member exchange mediates the effect of leader self-deprecating humour on silent behaviour and this effect is complete. It means that simply raising the level of self-deprecating humor in leaders does not directly affect employee silence. Companies also need to focus on the quality of LMX. It is worth noting in particular that some studies have concluded that the relationship between the use of leader humour and negative employee behaviour is not significant.70 This may be due to not observing the role of fully mediating variables,71 such as the change in model 2 compared to model 3 in this paper. In addition, we found that employee age as a control variable positively affects employee silence. Employees become more reticent in the workplace as they age.

Contribution

Our research is innovative and has the potential to make the following theoretical and practical contributions.

Firstly, we highlight the focus on negative employee behaviours. Although existing research has explored and found that leader humour has an important role in promoting positive employee behaviours, attention to negative employee behaviours remains relatively low.12 This paper examines the direct association between leader self-deprecating humour and employee silence. The findings on the one hand extend the theoretical research on leader humour and employee silence and on the other hand respond to Cooper et al’s10 suggestion that the examination of leader humour influencing employees’ more negative behaviours should be strengthened.

Secondly, this paper proposes a new logical path for research. Based on social exchange theory, we innovatively sort out the theoretical path of the mediating role of leader-member exchange and test the hypothesis with empirical analysis. There is limited literature that includes leader self-deprecating humour, leader-member and employee silence in the same theoretical framework, and our study can enrich the existing set of theoretical variables.

Thirdly, some new practical insights can be drawn from the empirical findings of this paper. Companies should make a conscious effort to develop and select humorous leaders who are willing to laugh at themselves. For example, companies can design and develop training programmes to enhance leaders’ sense of humour and encourage them to adapt their leadership style to use self-deprecating humour appropriately in the leadership process to enhance the quality of their relationships with their subordinates. Subordinate suggestion behaviour may also be increased by building a good leader-subordinate interaction. We have identified some new factors affecting employees’ psychological well-being and new ways to enhance it, and these findings may shed light on organisational human resource management practices.

Limitations and Prospect

There are also limitations in our study. This study only considered the mediating role of leader-member exchange in the relationship between humorous leadership and employee creativity from the perspective of social exchange, but there may be other paths of action. Future research could explore the role of mediating variables (eg emotions, psychological empowerment, work engagement, etc.) in the relationship from emotional and cognitive perspectives, and gain insight into how different styles of humorous leadership will impact on employee creativity. This study is based on companies from China due to the availability of data. However, there are inconsistencies in employees’ understanding of leader humour in different cultural contexts between China and the West. Some studies have shown differences in humour measures and the impact of humour on mental health between Chinese and Canadian employees.72 As globalisation accelerates and many business activities are conducted in different cultural contexts, cross-cultural leadership is becoming increasingly common. It is therefore important to explore the cross-cultural universality and differences in the connotations, triggers and consequences of leader humour and to advance cross-cultural comparative research. Future research could consider using a sample of Western cultural contexts to further validate the reliability of this paper’s findings. Alternatively, a cross-cultural comparative analysis of Eastern and Western cultures could be conducted to bring more references to the academic and practical community.

Declaration of Helsinki

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethical Considerations

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jilin University. All subjects read informed consent before participating this study and voluntarily made their decision to complete surveys.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participant(s) to publish this paper.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72091313).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Morrison EW. Employee voice and silence. J Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2014;1:173–197. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

2. Nechanska E, Hughes E, Dundon T. Towards an integration of employee voice and silence. Hum Resour Manage R. 2020;30(1):100674. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.11.002

3. Stein M. When does narcissistic leadership become problematic? Dick fuld at lehman brothers. J Manage Inquiry. 2013;22(3):282–293. doi:10.1177/1056492613478664

4. Memon AR, Jivraj S. Trust courage and silence: carving out decolonial spaces in higher education through student-staff partnerships. Law Teach. 2020;54(4):475–488. doi:10.1080/03069400.2020.1827777

5. Wijma B, Zbikowski A, Bruggemann AJ. Silence shame and abuse in health care: theoretical development on basis of an intervention project among staff. Bmc Med Educ. 2016;16:107–128. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0595-3

6. Hassan S, DeHart-Davis L, Jiang ZN. How empowering leadership reduces employee silence in public organizations. Public Admin. 2019;97(1):116–131. doi:10.1111/padm.12571

7. Kong DT, Cooper CD, Sosik JJ. The state of research on leader humor. Organ Psychol Rev. 2019;9(1):3–40. doi:10.1177/2041386619846948

8. Pundt A. The relationship between humorous leadership and innovative behavior. J Manage Psychol. 2015;30(8):878–893. doi:10.1108/JMP-03-2013-0082

9. Yam KC, Christian MS, Wei W, et al. The mixed blessing of leader sense of humor: examining costs and benefits. Acad Manage J. 2018;61(1):348–369. doi:10.5465/amj.2015.1088

10. Cooper CD, Kong DT, Crossley CD. Leader humor as an interpersonal resource: integrating three theoretical perspectives. Acad Manage J. 2018;61(2):769–796. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0358

11. Liu F, Chow IHS, Gong YY, et al. Affiliative and aggressive humor in leadership and their effects on employee voice: a serial mediation model. Rev Manag Sci. 2020;14(6):1321–1339. doi:10.1007/s11846-019-00334-7

12. Jing BF, Zhou X. A literature review of leadership humor and prospects. For Econ Manag. 2019;41(3):70–82. doi:10.16538/j.cnki.fem.2019.03.005

13. Goswami A, Nair PK, Grossenbacher MA. Impact of aggressive humor on dysfunctional resistance. Pers Indiv Differ. 2015;74:265–269. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.037

14. Martin R, Guillaume Y, Thomas G, et al. Leader–member exchange (LMX) and performance: a meta–analytic review. Pers Psychol. 2016;69(1):67–121. doi:10.1111/peps.12100

15. Mulligan R, Ramos J, Martín P, Zornoza A. Inspiriting innovation: the effects of leader-member exchange (LMX) on innovative behavior as mediated by mindfulness and work engagement. Sustainability-Basel. 2021;13(10):5409. doi:10.3390/su13105409

16. Tangirala S, Ramanujam R. Employee silence on critical work issues: the cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Pers Psychol. 2008;61(1):37–68. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00105.x

17. Harlos K. Employee silence in the context of unethical behavior at work: a commentary. Ger J Hum Resour Man. 2016;30(3):345–355. doi:10.1177/2397002216649856

18. Knoll M, Van DR. Authenticity employee silence prohibitive voice and the moderating effect of organizational identification. J Posit Psychol. 2013;8(4):346–360. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.804113

19. Lam LW, Xu AJ. Power imbalance and employee silence: the role of abusive leadership power distance orientation and perceived organisational politics. J Appl Psychol. 2019;68(3):513–546. doi:10.1111/apps.12170

20. Madrid HP, Patterson MG, Leiva PI. Negative core affect and employee silence: how differences in activation cognitive rumination and problem-solving demands matte. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100(6):1887–1898. doi:10.1037/a0039380

21. Bari MW, Ghaffar M, Ahmad B. Knowledge-hiding behaviors and employees’ silence: mediating role of psychological contract breach. J Knowl Manag. 2020;24(9):2171–2194. doi:10.1108/JKM-02-2020-0149

22. Kumar N, Liu ZQ, Jin YH. Evaluation of employee empowerment on taking charge behaviour: an application of perceived organizational support as a moderator. Psychol Res Behav Ma. 2022;15:1055–1066. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S355326

23. Emelifeonwu JC, Valk R. Employee voice and silence in multinational corporations in the mobile telecommunications industry in Nigeria. Empl Relat. 2019;41(1):228–252. doi:10.1108/ER-04-2017-0073

24. Li X, Xing L. When does benevolent leadership inhibit silence? The joint moderating roles of perceived employee agreement and cultural value orientations. J Manage Psychol. 2021;36(7):562–575. doi:10.1108/JMP-07-2020-0412

25. Poethke U, Klasmeier KN, Diebig M. Exploring systematic and unsystematic change of dynamic leader behaviours: a weekly diary study on the relation between instrumental leadership stress and health change. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2022;31(4):537–549. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2021.2012458

26. Cooper CD. Elucidating the bonds of workplace humor: a relational process model. Hum Relat. 2008;61(8):1087–1115. doi:10.1177/0018726708094861

27. Pundt A, Herrmann F. Affiliative and aggressive humour in leadership and their relationship to leader-member exchange. Occup Organ Psych. 2015;88(1):108–125. doi:10.1111/joop.12081

28. Martin RA, Puhlik-Doris P, Larsen G, et al. Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: development of the humor styles questionnaire. J Res Pers. 2003;37(1):48–75. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00534-2

29. Ali H, Mahmood A, Ahmad A, Ikram A. Humor of the leader: a source of creativity of employees through psychological empowerment or unethical behavior through perceived power? The role of self-deprecating behavior. Front Psychol. 2021;12:635300. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635300

30. Gkorezis P, Bellou V. The relationship between leader self-deprecating humor and perceived effectiveness: trust in leader as a mediator. Leadership Quart. 2016;37(7):882–898. doi:10.1108/LODJ-11-2014-0231

31. Tang L, Sun S. How does leader self-deprecating humor affect creative performance? The role of creative self-efficacy and power distance. Financ Res Lett. 2021;42:102344. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2021.102344

32. Hoption C, Barling J, Turner N. “It’s not you, it’s me”: transformational leadership and self-deprecating humor. Leadership Quart. 2013;34:4–19. doi:10.1108/01437731311289947

33. Feng XY. Calm down and enjoy it: influence of leader-employee mindfulness on flow experience. Psychol Res Behav Ma. 2022;15:839–854. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S360880

34. Wei H, Shan D, Wang L, Zhu S. Research on the mechanism of leader aggressive humor on employee silence: a conditional process model. J Vocat Behav. 2022;135:103717. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103717

35. Potipiroon W, Ford MT. Does leader humor influence employee voice? The mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of team humor. J Leadersh Org Stud. 2021;28(4):415–428. doi:10.1177/15480518211036464

36. Graen GB, Uhl-Bien M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quart. 1995;6(2):219–247. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5

37. Dinh JE, Lord RG, Gardner WL, et al. Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. Leadership Quart. 2014;25(1):451–465. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.005

38. Qu R, Janssen O, Shi K. Leader-member exchange and follower creativity: the moderating roles of leader and follower expectations for creativity. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2017;28(4):603–626. doi:10.1080/09585192.2015.1105843

39. Troster C, Van Quaquebeke N. When victims help their abusive supervisors: the role of LMX self-blame and guilt. Acad Manage J. 2021;64(6):1793–1815. doi:10.5465/amj.2019.0559

40. Maslyn JM, Uhl-Bien M. Leader-member exchange and its dimensions: effects of self-effort and other’s effort on relationship quality. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(4):697–708. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.4.697

41. Ionescu AF, Iliescu D. LMX organizational justice and performance: curvilinear relationships. J Manage Psychol. 2021;36(2):197–211. doi:10.1108/JMP-03-2020-0154

42. Tremblay M. Understanding the effects of (dis) similarity in affiliative and aggressive humor styles between supervisor and subordinate on LMX and energy. Humor. 2021;34(3):411–435. doi:10.1515/humor-2020-0082

43. Moin MF, Wei F, Weng Q, Ahmad Bodla A. Leader emotion regulation leader-member exchange (LMX) and followers’ task performance. Scand J Psychol. 2021;62(3):418–425. doi:10.1111/sjop.12709

44. Ouerdian EGB, Mansour N, Gaha K. Linking emotional intelligence to turnover intention: LMX and affective organizational commitment as serial mediators. Leadership Quart. 2021;42(8):1206–1221. doi:10.1108/LODJ-01-2021-0016

45. Tierney P, Farmer SM, Graen GB. An examination of leadership and employee creativity: the relevance of traits and relationships. Pers Psychol. 1999;52:591–620. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00173.x

46. Wulani F, Handoko TH, Purwanto BM. Supervisor-directed OCB and deviant behaviors: the role of LMX and impression management motives. Pers Rev. 2022;51(4):1410–1426. doi:10.1108/PR-06-2020-0406

47. Zhang YJ, Huang YC, Lu L. Influence of leader humoron employee’s voice: a moderated mediation model. Soft Sci. 2022;36:124–129.

48. Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing value. Stata J. 2004;4(3):227–241. doi:10.1142/9789812702142_0037

49. Liden RC, Sparrowe RT, Wayne SJ. Leader-member exchange theory: the past and potential for the future. Res Person Hum Resourc Manag. 1997;15:47–119.

50. Tangirala S, Ramanujam R. Employee silence on critical work issues: the cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Pers Psychol. 2010;61(1):37–68. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00105.x

51. Detert JR, Burris ER. Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad Manage J. 2007;50:869–884. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.26279183

52. Hsiung HH. Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: a multi-level psychological process. J Bus Ethics. 2012;107:349–361. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-1043-2

53. Kramarenko AV, Tan U. Validity of spectral analysis of evoked potentials in brain research. Int J Neurosci. 2002;112:489–499. doi:10.1080/00207450290025608

54. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, et al. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

55. Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr. 2009;76:408–420. doi:10.1080/03637750903310360

56. Lingard L. Language matters: towards an understanding of silence and humour in medical education. Med Educ. 2013;47:40–48. doi:10.1111/medu.12098

57. Lanfranco S. Humor silence and civil society in Nigeria. Voluntas. 2018;29(2):434–435. doi:10.1007/s11266-017-9897-2

58. Tremblay M, Gibson M. The role of humor in the relationship between transactional leadership behavior perceived supervisor support and citizenship behavior. J Leadersh Org Stud. 2016;23(1):39–54. doi:10.1177/1548051815613018

59. Wen ZL, Ye BJ. Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: competitors or backups? Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2014;46:714–725. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.00714

60. Bolin JH. Introduction to mediation moderation and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. J Educ Meas. 2014;51(3):335–337. doi:10.1111/jedm.12050

61. Whiteside DB, Barclay LJ. Echoes of silence: employee silence as a mediator between overall justice and employee outcomes. J Bus Ethics. 2013;116(2):254–266. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1467-3

62. Erkutlu H, Chafra J. Leader’s integrity and employee silence in healthcare organizations. Lead Heal Serv. 2018;32(3):419–434. doi:10.1108/LHS-03-2018-0021

63. Prouska R, Psychogios A. Do not say a word! Conceptualizing employee silence in a long-term crisis context. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2018;29(5):885–914. doi:10.1080/09585192.2016.1212913

64. Khassawneh O, Mohammad T, Ben-Abdallah R, et al. The relationship between emotional intelligence and educators’ performance in higher education sector. Behav Sci. 2022;12(12):511. doi:10.3390/bs12120511

65. O’Donovan R, De Brun A, McAuliffe E. Healthcare professionals experience of psychological safety voice and silence. Front Psychol. 2021;12:626689. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626689

66. Chen SC, Shao J, Liu NT. Reading the wind: impacts of leader negative emotional expression on employee silence. Front Psychol. 2022;13:762920.

67. Liao S, Van der Heijden B, Liu Y, Zhou X, Guo Z. The effects of perceived leader narcissism on employee proactive behavior: examining the moderating roles of LMX quality and leader identification. Sustainability-Basel. 2019;11(23):6597. doi:10.3390/su11236597

68. Khassawneh O, Elrehail H. The effect of participative leadership style on employees’ performance: the contingent role of institutional theory. Adm Sci. 2022;12(4):195. doi:10.3390/admsci12040195

69. Li W, Abdalla AA, Mohammad T, et al. Towards examining the link between green HRM practices and employee green in-role behavior: spiritual leadership as a moderator. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:383–396. doi:10.2147/prbm.s396114

70. Robert C, Dunne TC, Lun J. The impact of leader humor on subordinate job satisfaction: the crucial role of leader-subordinate relationship quality. Group. 2016;41(3):375–406. doi:10.1177/1059601115598719

71. Lee JY, Slater MD, Tchernev J. Self-deprecating humor versus other-deprecating humor in health messages. J Health Commun. 2015;20(10):1185–1195. doi:10.1080/10810730.2015.1018591

72. Chen GH, Martin RA. Humor styles and mental health among Chinese university students. Psychol Sci. 2007;30:219–223.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.