Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 12

Depression and pain: testing of serial multiple mediators

Authors Wongpakaran T , Wongpakaran N , Tanchakvaranont S, Bookkamana P , Pinyopornpanish M , Wannarit K, Satthapisit S, Nakawiro D, Hiranyatheb T, Thongpibul K

Received 12 April 2016

Accepted for publication 9 May 2016

Published 25 July 2016 Volume 2016:12 Pages 1849—1860

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S110383

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Wai Kwong Tang

Tinakon Wongpakaran,1 Nahathai Wongpakaran,1 Sitthinant Tanchakvaranont,2 Putipong Bookkamana,3 Manee Pinyopornpanish,1 Kamonporn Wannarit,4 Sirina Satthapisit,5 Daochompu Nakawiro,6 Thanita Hiranyatheb,6 Kulvadee Thongpibul7

1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Kingdom of Thailand; 2Department of Psychiatry, Queen Savang Vadhana Memorial Hospital, Chonburi, Kingdom of Thailand; 3Department of Statistics, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Kingdom of Thailand; 4Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand; 5Department of Psychiatry, Khon Kaen Regional Hospital, Khon Kaen, Kingdom of Thailand; 6Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand; 7Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Kingdom of Thailand

Purpose: Despite the fact that pain is related to depression, few studies have been conducted to investigate the variables that mediate between the two conditions. In this study, the authors explored the following mediators: cognitive function, self-sacrificing interpersonal problems, and perception of stress, and the effects they had on pain symptoms among patients with depressive disorders.

Participants and methods: An analysis was performed on the data of 346 participants with unipolar depressive disorders. The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Mini-Mental State Examination, the pain subscale of the health-related quality of life (SF-36), the self-sacrificing subscale of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, and the Perceived Stress Scale were used. Parallel multiple mediator and serial multiple mediator models were used. An alternative model regarding the effect of self-sacrificing on pain was also proposed.

Results: Perceived stress, self-sacrificing interpersonal style, and cognitive function were found to significantly mediate the relationship between depression and pain, while controlling for demographic variables. The total effect of depression on pain was significant. This model, with an additional three mediators, accounted for 15% of the explained variance in pain compared to 9% without mediators. For the alternative model, after controlling for the mediators, a nonsignificant total direct effect level of self-sacrificing was found, suggesting that the effect of self-sacrificing on pain was based only on an indirect effect and that perceived stress was found to be the strongest mediator.

Conclusion: Serial mediation may help us to see how depression and pain are linked and what the fundamental mediators are in the chain. No significant, indirect effect of self-sacrificing on pain was observed, if perceived stress was not part of the depression and/or cognitive function mediational chain. The results shown here have implications for future research, both in terms of testing the model and in clinical application.

Keywords: depressive disorder, mediator, serial mediation, multiple mediation

Introduction

It has long been recognized that pain and depression are closely related.1–5 Banks and Kerns6 introduced the diathesis-stress model for pain and depression, suggesting that patients suffering from chronic pain who become depressed may have had a certain premorbid psychological predisposition toward developing depression. Multiple factors are involved in the depression–pain linkage, including neurobiological, genetic, and precipitating environmental factors, as well as psychological, social, and cognitive influences.7–12 Another important model in medical and psychiatric contexts is Engel’s biopsychosocial model.13 Even though the term “biopsychosocial” is rather broad, its name helps remind clinicians of the components involved in the relationship between depression and pain.14–17 On the basis of this approach, cognitive abilities, which are the brain-based skills and mental processes required to accomplish any task and are part of biological and social factors commonly used in clinical practice, have been shown to be related to pain.18–22 Regarding psychosocial factors, psychological stress (which is presented as perceived stress, ie, the extent to which individuals perceive that the demands placed on them exceed their ability to cope) has also been shown to have a significant correlation with pain and depression.23–27 Other psychological factors that have been shown to be related to pain include self-efficacy,28 mastery,29 personal control,30,31 catastrophizing, hopelessness and helplessness,32 and mental defeatism.33 In addition, a person’s attachment style also plays a role in the relationship between depression and pain,34–38 and certain interpersonal problems are also correlated with a high prevalence of both pain and depression: in particular submissiveness and nonassertiveness, and self-sacrificing and friendly submissive behavior.39–41

It is well established that pain can cause depression, and depression can also lead to pain. Pain is even considered as a somatic symptom of depression.42–44 Symptoms of depression increase the risk of future episodes of pain, such as neck pain, low back pain, and cutaneous pain,45–47 and the greater the severity of depression, the higher the risk of pain.45 Moreover, a systemic review reported that symptoms of depression worsen the course of pain.48 Carroll et al46 showed that depression was a robust and independent predictor for the onset of an episode of neck and low back pain. Similarly, Schieir et al49 found that symptoms of depression predicted the trajectory of pain for up to 6 months. Using a structural equation model, Trudel-Fitzgerald et al50 notably stated that depression came before pain in cancer patients. The biological explanation for this extensive evidence of correlation is that depression and pain are thought to be mediated by the neurotransmitters serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine by means of different but overlapping neuroanatomical pathways.51

Not only does depression have a direct effect on the development of pain, some studies have also shown indirect effects (mediation) of depression on pain, while others showed depression as an intervening variable (between some variable and pain) in path analysis. For example, in the fear-avoidance model,52 depression appears as a mediator of prospective links between the fear-avoidance model and pain variables, which achieves a better prediction of model variables.53 In the communal coping model of catastrophizing,54 catastrophizing thought has a direct effect on pain intensity, and it also predicted the affective component of pain via depression. Self-sacrificing tendencies were found to moderate the relationship between pain and the physical symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis,55,56 which is associated with depression.57 Another study supporting a pathway from depression to pain was conducted by Saariaho et al.58 They revealed that the group of maladaptive schemas called “endangered” role (eg, disconnection rejection) showed pathways to depression, and from depression to pain disability in the pain patients, while the other group of maladaptive schemas, defined as the “encumbered” role (eg, self-sacrificing), exhibited a direct pathway to pain disability.

The models mentioned thus far illustrate depression as the only mediator or intervening variable. What is lacking in the current research is the role of other possible mediators, which should be included and tested in terms of elucidating the depression–pain linkage in depressed patients. Adding more justifiable variables strengthens the explanatory power of the proposed model. Therefore, other possible mediators operating in the biopsychosocial realm should also be included. This means considering other variables that may exist between depression and pain, or what may precede them if depression is an intervening or a mediating variable with respect to pain.

The primary aim of this study was to look for possible mediators of depression and pain, and to explore the proposed model that depression is a mediator or an intervening variable. All factors were tested simultaneously in a multiple (serial) mediation model to understand the causal order of the related mediators of the two conditions. To our knowledge, this has not yet been previously studied.

Participants and methods

Study design

This study was a secondary analysis of data taken from the Thai Study of Affective Disorders (THAISAD), a 12-month observational study of treatment outcomes among outpatients diagnosed with major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, and double depressive disorder.59 The study’s protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University. All participants provided written informed consent to be included in this study. The participants were assessed for their severity of depression and quality of life at baseline and then every 3 months for five visits. THAISAD was carried out between March 2011 and August 2012. Only data from baseline of THAISAD were used in this analysis.

THAISAD, although observational in nature, was designed to examine the roles psychosocial variables play with regard to depression outcomes. The predetermined psychosocial variables included in the study were as follows: attachment style, interpersonal problems, perceived social support, and perceived stress. This study describes the cross-sectional analysis carried out to establish any association between pain and depression, including the associated factors.

Participants

Three hundred and forty-six individuals, aged 18 years and older, participated in the study. Participants were diagnosed with major depressive disorder and/or dysthymic disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, by trained clinicians and psychiatrists, using the Thai version of Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory.60,61 Participants were receiving standard treatment from a multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers at eleven tertiary hospitals across Thailand.

Individuals excluded from the study were 1) those demonstrating comorbidity, or those who were pregnant, or lactating; 2) those suffering from severe substance abuse; 3) those with cognitive impairment based on their performances on the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE); 4) those with a history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; and/or 5) those who did not provide written, informed consent.

Measurements

Demographic data as well as psychosocial variables, as recorded by the participants, were collected by the research assistants. Other measurements used are as follows:

Pain assessment

The level of bodily pain experienced by the participants – one of eight components measured by the 36-item health-related quality of life scale (SF-36 version 2, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA)62 – was used as the main outcome in this study. The Thai version has already demonstrated good reliability.63 Two questions from the pain subscale are: 1) “How much bodily pain have you experienced during the past four weeks?” and 2) “During the past four weeks, how much has pained interfered with your normal work (including work outside the home and housework)?” The responses to these questions ranged from “not at all” to “a lot”. A composite score was used combining pain intensity and pain interference ratings into a single score, as it appeared to have greater validity and reliability when compared to a single item.64

Severity of depression

The severity of depression was assessed using the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17).65 The Thai versions of HAMD have demonstrated good reliability and validity in previous studies.66

Cognitive function

The MMSE-Thai 2002,67 which was modified from the original version by Folstein et al,68 was used. Information concerning participants’ level of education is required to interpret cognitive impairment or dementia using this version of MMSE. In this study, the total score for participants who completed at least elementary school was 30, and the cutoff score for cognitive impairment or dementia was 22. For those who had not completed elementary school, the cutoff score for cognitive impairment was 17. The total score for participants who were illiterate was 23, and the cutoff score for cognitive impairment for these participants was 14. Those whose scores were below the cutoff were excluded from the study.

Self-sacrificing

This subscale was selected from the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems scale, which assesses eight interpersonal problems, including dominance, vindictiveness, coldness, social inhibition, nonassertiveness, overaccommodation, self-sacrificing, and intrusion.69 An example of the “self-sacrificing state” is “I try to please other people too much”. The Thai version of 32-item Inventory of Interpersonal Problems has demonstrated good reliability and validity levels.70

The perceived stress scale

This ten-item, 5-point Likert scale instrument records how frequently people feel stressed.71 The Thai versions of perceived stress scale (PSS) have demonstrated good reliability and validity.72

Procedure

The authors hypothesized that depression (X) would indirectly influence pain (Y) intensity through causally linked multiple mediators of the cognitive function (M1), perception of stress (M2), and self-sacrificing factors (M3; Figure 1). Depression, pain, perceived stress, self-sacrificing, and cognitive function should have the same direction of association. As the relationship can be bidirectional, the causes and effects may not be precisely determined; nonetheless, the relationship between them, as shown in the multiple mediator model, cannot be ignored. Hence, the model was also tested for serial multiple mediation (SMM) by switching the mediator sequences to see how they would impact upon each other.

Correlations among pain intensity, proposed mediators, and severity of depression within the total sample were calculated using Pearson’s correlation. Then, the ability of the variables to account for variances within the HAMD due to pain association was analyzed with a statistical technique called a multiple mediation model.73 Both the parallel multiple mediation model (no relationship between mediators) and the SMM model (appear to be relationships between mediators) were used.

A multiple mediation model allows for a test of the combined effects of all proposed mediators to be carried out (ie, the total indirect effect) and can control for both collinearity among variables and mediation effects, meaning any significant mediation effects are unique.

To identify the direct and indirect effects of depression on pain, ordinary least-square path analysis was employed to estimate coefficients in the model.74 These models were tested using regression (to calculate statistics for specific paths) and bootstrapping (to generate a confidence interval [CI] for the mediation effects). These analyses yielded significance tests of specific paths and CIs for mediation effects.

The authors also tested the model in an alternative analysis base, based on what has been found in clinical practice. Since the results of statistical analyses may not always align with the theoretical background, clinically a slow-to-change variable such as inherent personality trait (or in this case self-sacrificing interpersonal style) should be regarded as a predisposing factor (or predictor),75 while other mediators function as precipitating or perpetuating factors. On the basis of this view, for this study, personality or self-sacrificing traits were considered the first variable (predictor, X), while pain served as the final variable (outcome, Y). Perceived stress (M1), cognitive function (M2), and depression (M3) were then considered to be the mediator variables. This model was tested to determine to what extent these mediators indirectly affect self-sacrificing interpersonal style’s influence on pain, in hope that the results might add something new or confirm previous ideas.

Multiple mediation analysis allows multiple mediators to be examined and reports the individual effects of each mediator while controlling for the others. Furthermore, covariates can be included in the model. If the upper and lower bounds of the 95% bias-corrected CIs do not contain zero, the indirect effect is considered significant. Beta weights provide an index of the magnitude of the indirect effect size. Similar to the basic idea of traditional mediation methods (Figure 1), “A” paths represent the association between the predictor of HAMD and mediator variables, in this case a1–a3. The “B” paths, meanwhile, represent the association between mediator variables and the pain outcome variable controlling for “A”, in this case b1–b3. Finally, the “C” path represents the total effect of HAMD on the pain outcome variable, having controlled for indirect effects. Indirect effects (ie, mediation effects) are defined as “a” × “b”. The total indirect effect is represented by the sum of “a1b1 + a2b2 + a3b3”.

As recommended by Preacher and Hayes,73 we used a bootstrapping method as it is considered the most powerful, most effective method to use with small samples, and the least vulnerable to Type I errors. In addition, bootstrapping does not assume normal distributions for any variable, and it is also a nonparametric resampling procedure. We resampled the data 10,000 times as recommended by Hayes;74 while we used a new method described by Preacher and Hayes73 to simultaneously test multiple mediators. Moreover, we considered bootstrapping to be the most powerful and appropriate method to obtain confidence limits for specific indirect effects under most conditions. In particular, bias-corrected bootstrapping was used whenever possible.

Covariates

Some factors can produce spurious associations, particularly in a nonexperimental study such as this one. Therefore, demographic data, including sex, age, education, marital status, employment status, and income levels, were statistically accounted for.

Statistical analyses

All analyses in this study were conducted using IBM SPSS 22 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). An examination of the raw data carried out prior to data analysis revealed that less than 4.3% of the data were missing. To ensure that data of all participants were included, a multiple imputation was used to estimate values for the missing data.

For the continuous variables, mean ± standard deviations and medians with ranges were used, whereas categorical data were presented as numbers and percentages. The statistical significance level for all the tests was set at a P-value of below 0.05.

For multiple mediation analysis, the SPSS macro PROCESS (model 4) was applied with three significant mediators. In SMM, a causal chain links the mediators with a specified direction of causal flow, leading to the creation of paths between mediators. For the serial analysis, SPSS macro PROCESS (model 6) was used, applying three significant mediators for each single analysis. As recommended by Hayes,74 the regression/path coefficients are all in unstandardized form as standardized coefficients generally have no useful substantive interpretation.

Model fit was also examined using the following criteria: a chi-square/df of ≤2, a P-value of >0.05, a comparative fit index of ≥0.95, and a root mean square error approximation of <0.06.76

Results

Among 346 participants, 264 were women, and 82 were men. An average age was 46.6 years (standard deviation [SD] =15.9). Forty-four percent were married, 23% were widowed, divorced, or separated, and 33% were single. In terms of education level, 23% completed high school and 34% completed a bachelor’s degree or higher. Seventy-six percent of the participants were employed, and 24% were unemployed.

Initial analyses

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations

Table 1 lists the mean values, standard deviations, and ranges for the sociodemographic and clinical variables. There was a significant correlation between HAMD scores, pain scores, and the proposed mediators, ie, PSS, cognitive function, and self-sacrificing. The correlation coefficients for the HAMD scores ranged from r=−0.15, P<0.01 to r=0.31, P<0.01, while the correlation coefficients for the pain scores ranged from r=−0.18, P<0.01 to r=−0.27, P<0.01. HAMD, as a predictor and independent variable, was also found to be significantly related to pain, as a dependent variable (r=−0.25, P<0.01).

| Table 1 Participants’ characteristics |

As recommended by Baron and Kenny,77 mediators have to be significantly correlated with both the predictors and outcome variables. All the proposed mediators here, including demographic, clinical, and psychosocial variables, were analyzed with predictor and criterion variables (pain), to establish their significance and to assess whether to include them in the path model. The analysis found that only perceived stress, cognitive function, and self-sacrificing could be included in the path model; therefore, they were submitted for multiple mediational analysis.

Test of the models

The parallel multiple model

This model evaluated whether perceived stress, cognitive function, and self-sacrificing would mediate the relationship between pain and depression. In the first regression, depression accounted for 9.7% of the unique variance in pain (R2=0.0968, t=4.4009, P<0.0001). After removing the effects of demographic variables, which are sex, age, education, marital status, employment status, and income, depression on its own accounted for 6.3% of the variance in pain scores (R2=0.0632, t=4.7992, P<0.0001).

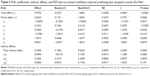

From the values given in Table 2, we see that perceived stress, self-sacrificing, and cognitive function significantly mediated the relationship between depression and pain, because the bootstrap CI was above zero while controlling for demographic variables. The total effect of depression on pain was significant (c=0.9720, CI =0.5375–1.4062, t=4.4009, P<0.001). Meanwhile, the regression coefficient estimates – based on the use of 95% bias-corrected CI as evidence of the mediation of total indirect and indirect effects for perceived stress, cognitive function, and self-sacrificing – were calculated as follows: total indirect =0.3496, CI =0.1830–0.5643, a2b2 =0.2430, CI =0.1015–0.4400, a1b1 =0.0460, CI =−0.0133–0.1552, and a3b3 =0.0606, CI =0.0010–0.1736, respectively. The total amount of variance accounted for by the overall model, which included depression and three proposed mediators, was 15.46%.

SMM analysis

This model uses the assumption that no mediator causally influences another. The authors tested each mediator’s impact on the others in terms of the whole indirect depression effect created by these three mediators.

Since three mediators were used, six different causal order models were produced (Table 3). All six models were compared in terms of the significant path created by each different causal order of the mediators. SMM 1 and SMM 2 yielded only two significant indirect paths, whereas most SMMs yielded five significant indirect paths (Table 4).

| Table 3 Possible serial models, according to different causal orders |

The causal order impacted upon the strength of the relationship between mediators, for example, the regression path coefficient for perceived stress to cognitive function in SMM 1 was −0.0563 (CI =−0.1101 to −0.0026), while the coefficient for cognitive function to perceived stress was −0.2202 (CI =−0.4304 to −0.0100) in SMM 3, denoting the latter had larger effect (Figure 2).The role of indirect effect cognitive function was found to be insignificant in parallel with multiple mediation, as the 95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI straddled zero (a1b1 =0.0460, CI =−0.0133−0.1552, t=1.1084, P=0.2684; Table 2), but became a significantly indirect effect when perceived stress was the next mediator (so: depression–cognitive function–perceived stress–pain) in SMMs 3, 4, and 6.

Similarly, for self-sacrificing, even though it had no indirect effect on its own but influenced perceived stress, the final pain score (depression–self-sacrificing–perceived stress–pain) was 0.0317, CI =0.0088–0.0790. This underlines the importance perceived stress plays as a mediator for depression.

It is interesting to note that SMM 3 – where cognitive function served as the first mediator (M1), perceived stress as the second (M2), and self-sacrificing as the third (M3) – was the only causal chain that yielded a significant indirect path for all three mediators.

As a whole, perceived stress, cognitive function, and the interpersonal problem of self-sacrificing did mediate the link between depression and pain, but only partially.

This study found that the worse the depression was, the more it would contribute to a perception of stress, a greater level of self-sacrificing, and reduced cognitive function, which in turn would together lead to greater pain being experienced.

Alternative analysis

To further examine the hypothesized causal chain mediation, the authors ran the data through an alternative analysis based on case formulation taken from the clinical practice mentioned in the “Introduction” section. In this alternative analysis, the authors tested why patients with self-sacrificing interpersonal style (as a predisposing factor) subsequently developed pain. In these cases, self-sacrificing served as the first (or independent) variable, with perception of stress, cognitive function, and depression serving as the mediators in that order. Pain served as the final (or dependent) variable (Figure 3). Initially, the total direct (c) for self-sacrificing was significant (1.450, 95% CI =0.601–2.300, t=3.3582, P=0.009), but after this alternative serial mediation analysis was used, its direct effect (c′) was reduced to a nonsignificant level (coefficient =0.8021, 95% CI =−0.0571–1.6613, t=1.8363, P=0.0672). It appeared that the effect of self-sacrificing on pain was fully mediated by these three mediators. The total indirect effect of self-sacrificing was still notably significant (coefficient =0.6483, 95% CI =0.2977–1.0643).

Three specific indirect paths where perceived stress was the first mediator (M1) were found to be significant, except for the chain in which cognitive function served as the second mediator (M2) (so: self-sacrificing–perceived stress–cognitive function–pain).

Discussion

In our alternative analysis, the model used and tested was based on clinical observation and the psychodynamic theory/approach, and was carried out within a real clinical practice. The analysis involved a test of the indirect effect of personality roots (eg, being self-sacrificing) on pain for individuals with depression. It helped to explain how self-sacrificing behavior leads to pain, primarily because it is mediated by perceived stress, poor cognitive function, and depression. This model is supported by the communal coping model, as explained by Sullivan et al,78 which suggests that catastrophizing functions as an interpersonal coping strategy are used “to maximize proximity or to solicit assistance or empathic responses from others”. Self-sacrificing interpersonal behavior significantly predicts catastrophizing, beyond the contribution of general distress. When perceived stress was added, leading to a negative cognitive function (implying a worsening ability to cope with problems), depression would ensue, which then led to pain, the level of which was in accordance with the person’s underlying characteristics of nonassertiveness.79 In fact, this should not be viewed as a causal relationship, like those in cross-sectional analyses.

It is interesting to note the role of perceived stress in the model. In the model, all three mediators played a role in the chain, even though cognitive function was first found to be insignificant in the parallel multiple model. However, cognitive function appeared as the first mediator, followed by perceived stress, in the three-serial model, where it played a more significant role. This also emphasizes the vital role played by perceived stress with respect to depression and pain.80 As found in the serial mediation model of depression and pain, this alternative model showed that perceived stress has the strongest indirect effect and is the most important link between the two mediators.

It is not common to test more than two mediators, even though a clinician may find many more variables that are related to the outcome. To our knowledge, this study might be the first test of a three-serial-mediator model for depression and pain. As claimed by Hayes,74 using three-serial mediators together forms a highly complex model, particularly for interpretation purposes, as the model can create up to eight distinct effects that depression has on pain: seven indirect effects and one direct effect. Discovering chains of causality is not only important for confirming theory and giving a basic understanding of the processes in question, but it also represents a first step toward reducing depression and pain, as it provides possible targets for intervention.

Serial mediation also made the data fit the model perfectly, more so than a parallel multiple mediator model. Even though SMM produced the same total indirect effects as parallel multiple mediation, the sequence of mediators yielded different results for the indirect chain of mediators. SMM 3, in which cognitive function served as the first mediator (M1), provided a significant chain that covered all three mediators, whereas using parallel multiple mediation did not give cognitive function a role as a mediator, as it did not have a significant, indirect effect.

Even though cross-sectional results preclude us from making a robust conclusion, using the multiple mediator approach does open the door to more interesting analytical tests of the complex causal model surrounding pain and depression. In other words, the cross-sectional design used here sets the stage for further analysis to be undertaken, using other interesting mediators.

The far higher computer performance that is available to us today opens up more opportunities for clinicians to test their assumptions concerning clinical problems that they are facing in real practice, as well as to gain greater understanding and to achieve better ways of helping patients. However, it remains a challenge to use relevant variables in a model and to interpret the results.

Strengths and limitations

This study has many strengths, including that it was the first test of the theoretical predictions made concerning depression patients based on the use of multiple variables within a biopsychosocial framework. This study, therefore, provided us with the opportunity to compare mechanisms and theories within a single, integrated model. In addition, using serial mediation gave us the opportunity to identify how one mediator impacts upon others in a chain of indirect effects.

One limitation of this study is its use of a cross-sectional design, as this prevented us from clearly defining the relationship between depression and pain. This means our model’s causal pathways need to be interpreted with care.

The study is also susceptible to confounding or epiphenomenal associations, for even though statistical control was applied, there was an absence of randomness. Further analysis as part of a prospective study should therefore be carried out in such a way that includes randomness. As claimed by Hayes,74 experimental, random assignment cannot by itself guarantee the presence of a causal order; however, a longitudinal study might provide stronger evidence. Finally, a questionnaire specifically designed to assess pain should be used to elaborate more upon the outcomes with regard to this symptom. Finally, since all the variables in this study were assessed using a self-reporting mechanism, a common method bias may have played a part in generating the results.

Clinical implication and future research

As mentioned in the “Introduction” section, with regard to the relationship between depression and pain, we should pay attention not only to specific variables per se, but also to their causal sequence. To simplify the results, it appears that in clinical practice we should notice that those people with self-sacrificing interpersonal problems, who also feel a high level of stress, tend to have higher levels of depression than those who have a lower level of stress. When these people get depressed, they tend to express pain, especially those who are lower in cognitive function.

In addition, the results have implications for future research in terms of testing the model and in terms of clinical application. From a theoretical point of view, these serial mediators of depression and pain support the complex model in a biopsychosocial context, although there may be many groups of mediators in the same biopsychosocial framework. This model, at least, substantiates clinicians’ beliefs about the importance of these variables. Clinicians might be aware of the possible mediators involved in their practices even though such mediators need to be further explored, and a definitive conclusion has not yet been reached. For clinicians, statistical significance of the model may not be as important as the model being clinically sound.

Conclusion

This study aimed to explore how certain variables serve as indirect mediators of depression and pain. It might be difficult to find a full mediation in such cases, since depression itself can be attributed to pain. In addition to the direct effects of depression, it is important to identify the mediators responsible for indirect effects, especially those that can be modified, such as cognitive function, perceived stress, and self-sacrificing behavior. Serial mediation may help us see how this link works and what the key mediators are in the chain. It is interesting to note that no significant indirect effect of self-sacrificing on pain was observed when perceived stress was not involved in the depression and/or cognitive function mediational chain. However, on the basis of the results of this study’s cross-sectional analysis, it is recommended that longitudinal relationships should be examined to confirm the more definitive causality terms over time.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), and was coordinated and supported by the Medical Research Network of the Consortium of Thai Medical School (MedResNet). Additional funding for the research was provided by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University. The authors thank Professor Bruce Weniger for his valuable comments. They also thank the following site-investigators who critically reviewed the study proposal and collected data:

Clinical investigators

Usaree Srisutasanavong (1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Kingdom of Thailand), Nattha Saisavoey (4Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand), Peeraphon Lueboonthavatchai (8Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand), Raviwan Nivataphand (8Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand), Nattaporn Apisiridej (9Trang Hospital, Trang, Kingdom of Thailand), Donruedee Petchsuwan (9Trang Hospital, Trang, Kingdom of Thailand), Thawanrat Srichan (10Lampang Hospital, Lampang, Kingdom of Thailand), Ruk Ruktrakul (10Lampang Hospital, Lampang, Kingdom of Thailand), Anakevich Temboonkiat (11Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Phramongkutklao Hospital, Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand), Namtip Tubtimtong (12Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Pitsanulok, Kingdom of Thailand), Sukanya Rakkhajeekul (12Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Pitsanulok, Kingdom of Thailand), Boonsanong Wongtanoi (13Srisangwal Hospital, Mae Hong Son, Kingdom of Thailand).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Denkinger MD, Lukas A, Nikolaus T, Peter R, Franke S; ActiFE study group. Multisite pain, pain frequency and pain severity are associated with depression in older adults: results from the ActiFE Ulm study. Age Ageing. 2014;43(4):510–514. | ||

Finset A, Wigers SH, Götestam KG. Depressed mood impedes pain treatment response in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(5):976–980. | ||

Moric M, Buvanendran A, Lubenow TR, Mehta A, Kroin JS, Tuman KJ. Response of chronic pain patients to terrorism: the role of underlying depression. Pain Med. 2007;8(5):425–432. | ||

Bonnewyn A, Katona C, Bruffaerts R, et al. Pain and depression in older people: comorbidity and patterns of help seeking. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(3):193–196. | ||

Demyttenaere K, Reed C, Quail D, et al. Presence and predictors of pain in depression: results from the FINDER study. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1–3):53–60. | ||

Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining high rates of depression in chronic pain: a diathesis-stress framework. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(1):95. | ||

Mongini F, Rota E, Evangelista A, et al. Personality profiles and subjective perception of pain in head pain patients. Pain. 2009;144(1–2):125–129. | ||

Bekkouche NS, Wawrzyniak AJ, Whittaker KS, Ketterer MW, Krantz DS. Psychological and physiological predictors of angina during exercise-induced ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(4):413–421. | ||

Pulvers K, Hood A. The role of positive traits and pain catastrophizing in pain perception. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17(5):330. | ||

Gale CR, Deary IJ, Cooper C, Batty GD. Intelligence in childhood and chronic widespread pain in middle age: the National Child Development Survey. Pain. 2012;153(12):2339–2344. | ||

Goesling J, Clauw DJ, Hassett AL. Pain and depression: an integrative review of neurobiological and psychological factors. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(12):421. | ||

Covic T, Adamson B, Spencer D, Howe G. A biopsychosocial model of pain and depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a 12-month longitudinal study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42(11):1287–1294. | ||

Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–136. | ||

Honerlaw KR, Rumble ME, Rose SL, Coe CL, Costanzo ES. Biopsychosocial predictors of pain among women recovering from surgery for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(2):301–306. | ||

Novy DM, Aigner CJ. The biopsychosocial model in cancer pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2014;8(2):117–123. | ||

Anderson RU, Orenberg EK, Chan CA, Morey A, Flores V. Psychometric profiles and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2008;179(3):956–960. | ||

Malt EA, Olafsson S, Lund A, Ursin H. Factors explaining variance in perceived pain in women with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2002;3:12. | ||

Ko HJ, Seo SJ, Youn CH, Kim HM, Chung SE. The association between pain and depression, anxiety, and cognitive function among advanced cancer patients in the hospice ward. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34(5):347–356. | ||

Moriarty O, McGuire BE, Finn DP. The effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93(3):385–404. | ||

Oosterman JM, Derksen LC, van Wijck AJ, Veldhuijzen DS, Kessels RP. Memory functions in chronic pain: examining contributions of attention and age to test performance. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(1):70–75. | ||

Kingma EM, Tak LM, Huisman M, Rosmalen JG. Intelligence is negatively associated with the number of functional somatic symptoms. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(11):900–905. | ||

Wongpakaran T, Wongpakaran N. Personality traits influencing somatization symptoms and social inhibition in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:157–164. | ||

Kuiper NA, Olinger LJ, Lyons LM. Global perceived stress level as a moderator of the relationship between negative life events and depression. J Human Stress. 1986;12(4):149–153. | ||

Candrian M, Farabaugh A, Pizzagalli DA, Baer L, Fava M. Perceived stress and cognitive vulnerability mediate the effects of personality disorder comorbidity on treatment outcome in major depressive disorder: a path analysis study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(9):729–737. | ||

Pizzagalli DA, Bogdan R, Ratner KG, Jahn AL. Increased perceived stress is associated with blunted hedonic capacity: potential implications for depression research. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(11):2742–2753. | ||

Bener A, Al-Kazaz M, Ftouni D, Al-Harthy M, Dafeeah EE. Diagnostic overlap of depressive, anxiety, stress and somatoform disorders in primary care. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2013;5(1):E29–E38. | ||

Menzies V, Lyon DE, Elswick RK, Montpetit AJ, McCain NL. Psychoneuroimmunological relationships in women with fibromyalgia. Biol Res Nurs. 2013;15(2):219–225. | ||

Miró E, Martínez MP, Sánchez AI, Prados G, Medina A. When is pain related to emotional distress and daily functioning in fibromyalgia syndrome? The mediating roles of self-efficacy and sleep quality. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16(4):799–814. | ||

Bierman A. Pain and depression in late life: mastery as mediator and moderator. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(5):595–604. | ||

Wang Q, Jayasuriya R, Man WY, Fu H. Does functional disability mediate the pain-depression relationship in older adults with osteoarthritis? A longitudinal study in China. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP382–NP391. | ||

McIlvane JM, Schiaffino KM, Paget SA. Age differences in the pain-depression link for women with osteoarthritis. Functional impairment and personal control as mediators. Womens Health Issues. 2007;17(1):44–51. | ||

Fahland RA, Kohlmann T, Hasenbring M, Feng YS, Schmidt CO. [Which route leads from chronic back pain to depression? A path analysis on direct and indirect effects using the cognitive mediators catastrophizing and helplessness/hopelessness in a general population sample]. Schmerz. 2012;26(6):685–691. German. | ||

Tang NK, Goodchild CE, Hester J, Salkovskis PM. Mental defeat is linked to interference, distress and disability in chronic pain. Pain. 2010;149(3):547–554. | ||

Tremblay I, Sullivan MJ. Attachment and pain outcomes in adolescents: the mediating role of pain catastrophizing and anxiety. J Pain. 2010;11(2):160–171. | ||

Martínez MP, Miró E, Sánchez AI, Mundo A, Martínez E. Understanding the relationship between attachment style, pain appraisal and illness behavior in women. Scand J Psychol. 2012;53(1):54–63. | ||

Meredith P, Strong J, Feeney JA. Adult attachment, anxiety, and pain self-efficacy as predictors of pain intensity and disability. Pain. 2006;123(1–2):146–154. | ||

Andersen TE. Does attachment insecurity affect the outcomes of a multidisciplinary pain management program? The association between attachment insecurity, pain, disability, distress, and the use of opioids. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(9):1461–1468. | ||

Sockalingam S, Blank D, A Jarad A, Alosaimi F, Hirschfield G, Abbey SE. The role of attachment style and depression in patients with hepatitis C. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20(2):227–233. | ||

Adler G, Gattaz WF. Pain perception threshold in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34(10):687–689. | ||

Lackner JM, Gurtman MB. Pain catastrophizing and interpersonal problems: a circumplex analysis of the communal coping model. Pain. 2004;110(3):597–604. | ||

Lackner J, Gurtman M. Patterns of interpersonal problems in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a circumplex analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(6):523–532. | ||

Seifsafari S, Firoozabadi A, Ghanizadeh A, Salehi A. A symptom profile analysis of depression in a sample of Iranian patients. Iran J Med Sci. 2013;38(1):22–29. | ||

Wrodycka B, Chmielewski H, Gruszczyński W, Zytkowski A, Chudzik W. [Masked (atypical) depression in patients with back pain syndrome in outpatient neurological care]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2006;21(121):38–40. Polish. | ||

Kroenke K. Patients presenting with somatic complaints: epidemiology, psychiatric comorbidity and management. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(1):34–43. | ||

Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML, Refshauge K, et al. Symptoms of depression and risk of new episodes of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67(11):1591–1603. | ||

Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Côté P. Depression as a risk factor for onset of an episode of troublesome neck and low back pain. Pain. 2004;107(1–2):134–139. | ||

Schieir O, Thombs BD, Hudson M, et al. Prevalence, severity, and clinical correlates of pain in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(3):409–417. | ||

Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML, Refshauge K, et al. Symptoms of depression as a prognostic factor for low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2016;16(1):105–116. | ||

Schieir O, Thombs BD, Hudson M, et al. Symptoms of depression predict the trajectory of pain among patients with early inflammatory arthritis: a path analysis approach to assessing change. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(2):231–239. | ||

Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Savard J, Ivers H. Which symptoms come first? Exploration of temporal relationships between cancer-related symptoms over an 18-month period. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(3):329–337. | ||

Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, Hudson J, Iyengar S, Demitrack MA. Effects of duloxetine on painful physical symptoms associated with depression. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(1):17–28. | ||

Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception – I. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21(4):401–408. | ||

Seekatz B, Meng K, Faller H. [Depressivity as mediator in the fear-avoidance model: a path analysis investigation of patients with chronic back pain]. Schmerz. 2013;27(6):612–618. German. | ||

Thorn BE, Ward LC, Sullivan MJ, Boothby JL. Communal coping model of catastrophizing: conceptual model building. Pain. 2003;106(1–2):1–2. | ||

Hyphantis T, Goulia P, Carvalho AF. Personality traits, defense mechanisms and hostility features associated with somatic symptom severity in both health and disease. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(4):362–369. | ||

Bai M, Tomenson B, Creed F, et al. The role of psychological distress and personality variables in the disablement process in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2009;38(6):419–430. | ||

Chance SE, Reviere SL, Rogers JH, et al. An empirical study of the psychodynamics of suicide: a preliminary report. Depression. 1996;4(2):89–91. | ||

Saariaho T, Saariaho A, Karila I, Joukamaa M. Early maladaptive schema factors, pain intensity, depressiveness and pain disability: an analysis of biopsychosocial models of pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(14):1192–1201. | ||

Wongpakaran T, Wongpakaran N, Pinyopornpanish M, et al. Baseline characteristics of depressive disorders in Thai outpatients: findings from the Thai Study of Affective Disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:217–223. | ||

Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(20):22–23. | ||

Kittirattanapaiboon P, Khamwongpin M. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.)-Thai Version. J Ment Health Thai. 2005;13(3):126–136. | ||

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. | ||

Jirarattanaphochai K, Jung S, Sumananont C, Saengnipanthkul S. Reliability of the medical outcomes study short-form survey version 2.0 (Thai version) for the evaluation of low back pain patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88(10):1355–1361. | ||

Jensen MP. The validity and reliability of pain measures in adults with cancer. J Pain. 2003;4(1):2–21. | ||

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. | ||

Lotrakul M, Sukkhanit P, Sukying C. The development of Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression – Thai version. J Psychiatr Assoc Thai. 1996;41:235–246. | ||

Thai Cognitive Test Development Committee 1999. Mini-Mental State Examination-Thai 2002. Bangkok: Institute of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand; 2002. | ||

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. | ||

Horowitz LM, Alden LE, Wiggins JS, Pincus AL. Inventory of Interpersonal Problems Manual. Odessa, FL: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. | ||

Wongpakaran T, Wongpakaran N, Sirithepthawee U, et al. Interpersonal problems among psychiatric outpatients and non-clinical samples. Singapore Med J. 2012;53(7):481–487. | ||

Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988:31–67. | ||

Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T. The Thai version of the PSS-10: an investigation of its psychometric properties. Biopsychosoc Med. 2010;4:6. | ||

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. | ||

Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. | ||

Schauenburg H, Kuda M, Sammet I, Strack M. The influence of interpersonal problems and symptom severity on the duration and outcome of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychother Res. 2000;10(2):133–146. | ||

Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. | ||

Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. | ||

Sullivan MJL, Thorn B, Keefe FJ, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:52–64. | ||

Pearson KA, Watkins ER, Mullan EG. Submissive interpersonal style mediates the effect of brooding on future depressive symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(10):966–973. | ||

Malin K, Littlejohn GO. Stress modulates key psychological processes and characteristic symptoms in females with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31(6 Suppl 79):S64–S71. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.