Back to Journals » International Journal of Nanomedicine » Volume 15

Cyanobacteria – A Promising Platform in Green Nanotechnology: A Review on Nanoparticles Fabrication and Their Prospective Applications

Authors Hamida RS , Ali MA, Redhwan A, Bin-Meferij MM

Received 19 May 2020

Accepted for publication 20 July 2020

Published 13 August 2020 Volume 2020:15 Pages 6033—6066

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S256134

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Anderson Oliveira Lobo

Reham Samir Hamida,1 Mohamed Abdelaal Ali,2 Alya Redhwan,3 Mashael Mohammed Bin-Meferij4

1Molecular Biology Unit, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt; 2Biotechnology Unit, Department of Plant Production, College of Food and Agriculture Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 3Department of Health, College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 4Department of Biology, College of Science, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Mashael Mohammed Bin-Meferij; Reham Samir Hamida Tel +966 554477376

; +20 1156298937

Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Abstract: Green synthesis of nanoparticles (NPs) is a global ecofriendly method to develop and produce nanomaterials with unique biological, physical, and chemical properties. Recently, attention has shifted toward biological synthesis, owing to the disadvantages of physical and chemical synthesis, which include toxic yields, time and energy consumption, and high cost. Many natural sources are used in green fabrication processes, including yeasts, plants, fungi, actinomycetes, algae, and cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria are among the most beneficial natural candidates used in the biosynthesis of NPs, due to their ability to accumulate heavy metals from their environment. They also contain a variety of bioactive compounds, such as pigments and enzymes, that may act as reducing and stabilizing agents. Cyanobacteria-mediated NPs have potential antibacterial, antifungal, antialgal, anticancer, and photocatalytic activities. The present review paper highlights the characteristics and applications in various fields of NPs produced by cyanobacteria-mediated synthesis.

Keywords: nanoparticles, nanomaterials, cyanobacteria, green synthesis, physicochemical properties

Introduction

Nanotechnology is an emerging field that includes synthesis, characterization, and development of various nanomaterials,1,2 that have significant roles in daily life, providing valuable products that improve industrial production, agriculture, communication, and medicine.3 Currently, around 1000 commercial nanoproducts are available in world markets.4,5 The term “nano” denotes any particles or materials with at least one nanosized (1–100 nm) dimension. Nanoparticles (NPs) differ significantly from their bulk materials in terms of physical, chemical, and biological properties.6 These differences are mainly due to their high surface area to volume ratio, which results in considerable differences in catalytic and thermal activities, melting point, conductivity, mechanical properties, and optical absorption. These properties make NPs applicable in almost all fields.7

NPs have significant roles in bio-diagnostic and optical biosensing, nanophotonics, and imaging and treatment of many diseases affecting human health.8 Silver NPs (Ag-NPs) can interact effectively with microbe surfaces due to their small size and large surface area and are thus used as antimicrobial agents.9 Ag-NPs synthesized using Fusarium Keratoplasticum and embedded in cotton fiber showed significant antibacterial activity against pathogenic bacteria.10 Carbon nanotubes have a key role in drug delivery, because of their capacity to carry drugs and control their release into target cells.11 Quantum dot NPs have been used to detect the location of malignant cells inside the body.12 Iron oxide NPs are used in resonance imaging and diagnosis of tumors.13 Gold NPs (Au-NPs) are in high demand for various applications in multiple fields owing to their low toxicity.14 In addition, Au-NPs have high photothermal and photoacoustic activity, making them suitable for use in photothermal therapy for cancer. Other biogenic NPs such as copper oxide NPs,15 zinc oxide NPs,16 selenium NPs,17 acted as potent anticancer agents. The variation in NP shapes, including spherical, cubic, needles, triangular, rod, etc., enables them to be used in diverse areas such as device manufacture, electronics, optics, and biofuel cells (Figure 1).18

|

Figure 1 Various shape of nanoparticles. |

The physicochemical routes used to produce NPs are often unwieldy, expensive, and result in liberation of toxic byproducts that threaten ecological systems.19 To avoid these drawbacks, green synthesis of NPs using biogenic agents has become an alternative to chemical and physical synthesis.20 Diatoms, mushrooms, algae, plants, fungi, bacteria, actinomycetes, lichen, cyanobacteria, and microalgae have been shown to successfully reduce metal precursors to their corresponding NPs.21 Intra- and extracellular green synthesis techniques have been developed to reduce bulk materials to nanoforms using biological extracts.22 These nanomaterials can be synthesized in the presence of biocompounds such as flavanones, amides, enzymes, proteins, pigments, polysaccharides, phenolics, terpenoids, or alkaloids, to aid the reduction and stabilization of NPs.21 A high surface area to volume ratio is the target physical feature of NPs, as it confers their versatile applicability and ability to withstand harsh conditions.23 The shape and size of NPs synthesize by microorganisms, can be controlled by various abiotic and biotic factors, including pH, temperature, the nature of the microorganisms, their biochemical activity, and interactions with heavy metals.24–26

In the past few years, the synthesis of NPs using cyanobacteria has become an active research field.24,27 Cyanobacteria are a diverse group of photoautotrophic prokaryotes that exist in a wide range of ecosystems.28 They are distinguished by their ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen (N2) by reducing nitrogen gas to ammonia using nitrogen reductase enzymes. This is a significant advantage in their role in biotransformation of metals to NPs,19 as they possess the ability to eliminate heavy metal ions from their surrounding environment. Furthermore, they contain various biomolecules including secondary metabolites, proteins, enzymes, and pigments that confer important biological properties such as antimicrobial and anticancer activity.27,29,30 In addition to these features, cyanobacteria have a high growth rate that facilitates high biomass production. Thus, they represent important nanotechnology-mediated microorganisms that can act as nanobiofactories for NPs.31,32 Although there have been several detailed reviews of biological synthesis using microorganisms, few studies have focused on synthesis of NPs using cyanobacteria.

The current paper comprehensively reviews work on cyanobacteria-mediated fabrication of NPs, their abiotic and biotic conditions used during biosynthesis process including illumination, pH, temperature, type of synthesis process (extracellular and intracellular), followed with the factors influence on the synthesis process of NPs, the corresponding mechanisms of the biological synthesis, applications of NPs in various areas as well as the toxicity strategies of NPs against living cells.

Classification of NPs

NPs can be classified according to various factors, such as shape and dimension, phase compositions, nature, and origin (Figure 2).33 For instance, natural NPs include those that exist in the biosphere as a result of fabrication from heavy metals by living organisms, as well as those generated incidentally by forest fires, volcanic eruptions, weathering of rocks, explosion of clay minerals, soil erosions, and sandstorms.34 By contrast, engineered NPs are produced using chemical and physical routes. NPs can also be classified according to their chemical nature. Inorganic NPs include metal and metal oxide NPs such as silver, gold, platinum, titanium oxide, iron oxide, copper oxide, and zinc oxide NPs. Organic NPs include carbon NPs, N-halamine compounds, and chitosan NPs.21

|

Figure 2 Nanoparticles classifications.Note: ©2019. Dove Medical Press. Adapted from Ahmad S, Munir S, Zeb N, et al. Green nanotechnology: a review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles–an ecofriendly approach. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:508733 and adapted from J Microbiol Methods, 163, Khanna P, Kaur A, Goyal D. Algae-based metallic nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and applications, page number:105656, Copyright (2019), with permission from Elsevier.19 |

Synthesis and Characterization of NPs

There are several methodologies for NP synthesis, including conventional methods such as chemical and physical approaches as well as modern methods such as biological synthesis using natural living organisms,25 enzymes,35 vitamins,36 etc.6 The chemical routes are a type of bottom-up fabrication method, in which the atom assembled to nuclei and then grown to NPs.37 In chemical methods, the main components are the precursor metals and the stabilizing and reducing agents. Reducing agents include sodium citrate, ascorbate, and sodium borohydride;38 stabilizing agents include polyvinyl pyrrolidone, starch, and sodium carboxyl methylcellulose.39 Physical synthesis strategies belong to top-down route, in which, the metals are converted to their nanoforms using physical approaches such as laser ablation,40 mechanical milling,41 and sputtering.37,42

The drawbacks of the physicochemical approaches include power consumption, high cost, and a slow production rate, and, most importantly, these processes are not more eco-friendly due to their toxic yields that threaten ecological systems.6,18 Thus, there are global efforts towards development and usage of eco-friendly methods to synthesize NPs.

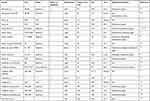

Green chemistry represents an advanced version of bottom-up nanotechnology approaches used to fabricate NPs.19 But still now, biological synthesis process fights many obstacles to compete physicochemical synthesis such as obtaining uniform shape and size of NPs.43 The aim of the biological synthesis methodology is to utilize natural sources to convert bulk material into nanoscaled particles with unique properties.32 The natural sources used in biofabrication of NPs vary from unicellular to multicellular organisms, moreover; this process can be carried out in the presence of single proteins, enzymes, pigments, etc.21 The unicellular organisms include bacteria,44 cyanobacteria,31 and diatoms,45 while multicellular organisms include algae and plant.46,47 The variety of potential natural sources and biomolecules facilitate the production of NPs with different unique properties. NPs are also subjected to various characterization analyses to assess their physical and chemical properties, including size, distribution, dispersion, stability, charge, and surface morphology.48,49 These analyses use spectroscopic techniques such as ultraviolet (UV)-visible spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), zeta potential, dynamic light scattering, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to determine wavelength ranges,27 and the chemical composition of biocoats surrounding biogenic NPs,31 and to confirm the formation of NPs, as well as characterizing their charge and hydrodynamic diameter.50 X-ray based analyses such as X-ray diffraction (XRD),49 X-ray photo-electron spectroscopy (XPS),23 and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDAX or EDS) are employed to evaluate composition, structure and crystal phase, structure and crystal phase.49 Microscopic techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high-resolution TEM, and atomic force microscopy are used to determine the size and morphological appearance of NPs.43,51 Also, there are several techniques perform to estimate the magnetic properties of NPs such as ferromagnetic resonance (FMR), vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM), etc. (Table 1).52,53

|

Table 1 Techniques Performed to Characterize Nanoparticles |

Potential Mechanisms of Green Synthesis Methods

The method of biofabrication of NPs differs from organism to another.54 Moreover, differences are found among different strains of the same species.55,56 Naturally, NPs are synthesized when microorganisms are exposed to toxic substances, in response to which they secrete extracellular substances to capture the material, or mediated through electrostatic interactions.54,57 Mukherjee et al showed that attraction electrostatic forces were among the factors aiding the reduction process of NPs in fungal cells.57 The biotransformation of NPs follows a general pattern wherein metal ions are trapped in the microbial cells or on the microbial surface in the presence of enzymes, and then reduced to form NPs.54 Furthermore, the reduction of NPs by microorganisms can be classified into intracellular and extracellular synthesis (Figure 3).

Intracellular Synthesis of NPs

Intracellular formation of NPs refers to cases where the reduction of bulk material into NPs is performed inside host cells under the control of various biological factors.20 Methods for in vivo synthesis of NPs in the laboratory involve three general steps: i) culturing the target microorganisms; ii) the interaction between the precursor solution and living cells; and iii) the separation and purification of NPs from cells for characterization using physicochemical techniques.24 In the latter step, the mixture of living microorganisms and precipitated NPs is centrifuged at 12,000 g. The pellets are then washed multiple times with distilled water for direct examination, and/or the cells are lysed using methods such as sonication to extract NPs for analysis (Figure 4).58

Intracellular interactions between bulk materials and microorganisms can be achieved by two different protocols. The first involves collecting cellular biomass of target microorganisms in the logarithmic phase by centrifugation, then washing this biomass to remove any traces of salts from the medium.59 The cleaned biomass is dissolved in water and mixed with a suitable concentration of precursor material solution. In the second method, microorganisms are individually cultured along with the bulk material solution and kept under culture conditions for 2 weeks.60

In cyanobacteria, ions are intracellularly reduced by electrons produced via the electron transport system, including energy-generating reactions in photosynthesis and, to some extent, in the respiratory electron transport system as a result of the existence of enzymes such as NADH-dependent reductases and redox reactions occur in the cytoplasm, thylakoid membranes, and cell membranes.22,61,62

Lengke et al showed that after reaction between Plectonema boryanum UTEX 485 system and silver nitrate, spherical, octahedral, and anhedral Ag-NPs were precipitated inside cells and in the culture solution.24 They suggested that the silver ions were reduced by an intracellular electron donor or exported by a membrane transporter system. This indicates that the metabolic status (eg, respiration or photosynthesis) and the growth phase of an organism determine its ability to synthesize NPs. Remarkably, P. boryanum was shown to reduce gold(III)-chloride solutions to Au-NPs intracellularly.63 The authors attributed the biorecovery mechanism of P. boryanum strains to either the gold(III)-chloride solution or the acidic medium, which killed cyanobacteria and liberated more organic sulfur, leading to further precipitation of gold particles. The interactions of cyanobacteria or organic material released through the cyanobacterial membrane with gold(III)-chloride enhanced the growth of metallic Au-NPs.

Kalishwaralal et al suggested that nitrate reductase enzymes may help to induce the enzyme responsible for synthesis of Ag-NPs in Bacillus licheniformis.64 Another study showed that nitrogenases (nitrogen-fixing enzymes) may be potent reducing agents for fabrication of gold ions into Au-NPs.65 Shabnam and Pardha-Saradhi reported that thylakoids extracted from Potamogeton nodosus (an aquatic plant) and Spinacia oleracea (a terrestrial plant) may have been responsible for the fabrication of gold ions into Au-NPs during photochemical reactions.66 Dahoumane et al suggested that polysaccharides and other macromolecules may be responsible for internal reduction and stabilization of NPs.67 Other reports have suggested that cyanobacterial pigments act as potent bioreductant molecules that intracellularly reduce bulk material into NPs.68,69

Extracellular Synthesis of NPs

Extracellular synthesis takes place outside the cell, with exuded biological molecules such as pigments, ions, proteins, enzymes, hormones, and antioxidants having a significant role in the reduction process of NPs.70,71 These biomolecules act as reducing and capping agents during the biofabrication process. Various methods exist for extracellular synthesis of NPs, including use of cell-free culture media, cell biomass extracts, and biomolecules (Figure 5).

Cell-Free Media

NPs can be synthesized using the culture media of microorganisms after removal of biomass by centrifugation. The filtrated extracellular culture media are mixed with metal precursor solutions under certain conditions to synthesis NPs. Keskin et al tested five cyanobacterial strains and showed that cell-free culture media of Synechococcus sp. were able to synthesis Ag-NPs under light conditions.72 Ag-NPs were also extracellularly synthesized using the supernatant of Pseudomonas sp. THG-LS1.4 strain.73 Many studies have demonstrated the vital role of biocontents such as enzymes, antioxidants, and phenolic and alkaloid compounds present in the cell-free culture in controlling the bioreduction process of NPs. Shivaji et al suggested that biomolecules such as NADH-reductases and sulfur-containing proteins in the cell-free supernatant are involved in biofabrication of metallic NPs.74

Cell Biomass Filtrate

Several reports describe the cell biomass filtrate synthesis approach, in which microorganism cultures are centrifuged and the pellets washed at least three times with distilled water to eliminate any excess metal from the medium.31,32,75 Then, the cleaned pellets are freeze-dried using a lyophilizer or dried in an oven almost at 40 °C, then crushed using a mortar and pestle. The resulting fine powder is mixed with distilled water then filtrated using Whatman filter paper. Finally, the filtrate is mixed with a metal precursor solution and incubated under suitable conditions. In this method, active biomoieties such as proteins and enzymes in the cells filtrate have significant roles in the biofabrication and stabilization of NPs.31 Other route mentioned by Hassan et al in which cell biomass collected at mid-exponential phase and wash several times to exclude any trace elements then soaked in distilled water for specific time. Afterward, the mixture is centrifuged, and the supernatant is used for NPs synthesis.15

Biomolecule-Based NP Synthesis

Cyanobacteria, microalgae, actinomycete, algae, etc. are distinguished by the predominance of pigments in their cells, such as carotenoid,76 C-phycocyanin,69 and R-phycoerythrin,77 that are able to synthesis NPs. C-phycocyanin is a blue photosynthetic accessory pigment that forms part of phycobilisomes, structures attached to thylakoids involved in light harvesting and transferring electrons toward photosystem II reaction centers.78,79 It has been shown that C-phycocyanin controls electron transfer and has the ability to bind to heavy metals.80,81 Recent studies have demonstrated the role of C-phycocyanin in fabrication of NPs; Pate et al showed that utilizing C-phycocyanin extracted from two different cyanobacteria species (Spirulina and Limnothrix species) resulted in production of Ag-NPs with different shapes and sizes.55 The authors attributed these differences in morphological features to the fact that the two C-phycocyanin preparations differed in purity and molecular weight. Also, they showed that there was a relationship between the ability of C-phycocyanin to synthesis NPs and the presence of light, as the pigment failed to reduce silver nitrate into Ag-NPs under dark conditions. Wei et al demonstrated the importance of C-phycocyanin extracted from Spirulina as a protective (capping) agent during the reduction process of silver nitrate into Ag-NPs.82 El Naggar et al reported that a proteinaceous pigment phycocyanin isolated from Nostoc linckia reduced silver nitrate into Ag-NPs under direct illumination (2400–2600 Lux) for 24 h at room temperature.69 In another study, phycoerythrin was extracted from Nostoc carneum and used as a reducing agent to synthesize Ag-NPs.83 Mubarak Ali et al successfully synthesized cadmium sulfide (CdS) NPs using C-phycoerythrin extracted from cyanobacteria species Phormidium tenue NTDM05.27 The mechanism by which C-phycocyanin mediates Ag-NPs synthesis is not clear; however, Patel et al suggest that it is similar to the mechanism of the red pigment R-phycoerythrin extracted from red algae, which can synthesize Ag-NPs without the addition of any reductant materials.55

Many studies have considered the role of proteins in stabilization and reduction of NPs.20,31,69 Bharde et al showed that cationic proteins secreted by Verticillium sp. and Fusarium oxysporum had hydrolytic activity, which enabled them to reduce and/or cap magnetite NPs.84 Reddy et al found that a bacterial protein of molecular weight between 25 and 66 kDa contributed to the reduction process of Au-NPs, whereas a protein of molecular weight between 66 and 116 kDa was responsible for SNP fabrication.85 Khalifa et al suggested that amino acids and proteins acted as stabilizing and reducing agents in the biofabrication process of metal nanoparticles (MNPs).86 Mubarak Ali et al showed that the presence of amino, carboxyl, sulfate, etc. groups in the amino acid sequence of cyanobacterial proteins facilitates the bioreduction process of extremely small NPs with uniform particle size distribution.87 Govindaraju et al performed extracellular synthesis of silver-gold core shell NPs, in addition to Ag-NPs and Au-NPs, using a single cell protein Spirulina plantensis.8 They identified the FTIR bands at 1653, 1541, and 1242 cm−1 as amide I–III bands of polypeptides/proteins, and suggested that algal proteins played a crucial part in the stabilization process of these NPs. Rahman et al reported that under metal stress, new or modified proteins were expressed to perform dual functions, fabricating precursor materials into CuO NPs and acting as stabilizing agents.88 They showed that a 22 kDa protein of Phormidium was responsible for the reduction of copper sulfate into copper oxide NPs. Rosken et al first detected Au-NPs in the extracellular polymeric material of vegetative cells and the heterocyst polysaccharide layer of Anabaena cylindrica.89

Many studies have investigated the roles of various enzymes, including nitrate reductases and NADH-dependent enzymes in the bioreduction process of NPs.65 Furthermore, Yin et al reported that superoxide dismutase has a vital role in the extracellular production of Ag-NPs using F. oxysporum.54 Mostly, assimilatory type of nitrate reductases is metalloproteins having molybdenum ions as cofactor and catalyzes several reactions in nitrogen, carbon and sulfur cycle. Many studies have demonstrated the importance of these enzymes as a potent reducing agent in the biofabrication process of MNPs.90

Oza et al suggested that nitrate reductase aided the NADH-dependent extracellular synthesis of Au-NPs by Chlorella pyrenoidosa.65 Brayner et al synthesized Au-NPs, Ag-NPs, Pt NPs, and Pd NPs in the presence of cyanobacteria using nitrogenases as reducing agents.91 They chose three strains, Calothrix pulvinate, Anabaena flos-aquae, and Leptolyngbya foveolarum, to form the NPs. C. pulvinate synthesized Pd and Pt NPs after 30 min and 15 days, respectively, Au-NPs after a few hours, and Ag-NPs after 24 h. By contrast, when the same precursor materials and strains were incubated with nitrogenases, Pd and Pt, Au, and Ag NPs were formed after 2 h, 72 h, and 10 min, respectively.

Morsy et al used extracellular polysaccharides (EPSs) from Nostoc commune to reduce silver nitrate to Ag-NPs.92 Briefly, they mixed 10 g of dried cyanobacteria with water, suspended the mixture in 100 mL of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7), and homogenized it in a blender at medium velocity for 10 s, followed by stirring overnight at ambient temperature. The suspension was then homogenized again at least three times for 10 s and left to stand at ambient temperature for 10 min. The upper layer (polysaccharides) was removed using a spatula, and the lower aqueous layer was centrifuged at 6000 x g for 10 min at 20 °C. The pellets were discarded, and the supernatant containing the water-soluble fraction of the EPSs was dialyzed overnight against distilled water and freeze-dried using a lyophilizer. Then, 50 mL of the aqueous EPS solution (10 mg/mL) was added to 30 mM of silver nitrate solution. The reaction was autoclaved at 15 psi and 121 °C for 5 min. To precipitate biogenic Ag-NPs the mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 x g for 30 min at 20 °C. They reported that the EPSs functioned as potent reducing and capping agents, and showed that coating Ag-NPs with EPSs prevented the particles from coming into contacting with oxygen and increased their stability.

Factors Influencing Biofabrication of NPs Using Microorganisms

Many factors should be considered during biological synthesis, including illumination, time of exposure, pH, temperature, and concentration. Control of these factors can facilitate the production of NPs with suitable physicochemical properties.22,67

Illumination

The presence or absence of light has an important role in the biosynthesis of NPs. Some researchers report that light is needed at least to accelerate the bioreduction process for synthesis of NPs.93 Patel et al suggested that illumination conditions are significant factors controlling the intracellular and extracellular synthesis of Ag-NPs using phototrophic cyanobacteria.55 They found that some cyanobacteria could not produce NPs under dark conditions. However, under the same conditions but after exposure to light, the same strains were able to fabricate Ag-NPs from silver nitrate. On the other hand, other strains including Anabaena sp., Limnothrix sp., and Synechocystis sp. were able to produce NPs under both light and dark conditions. This can be explained by the fact that different strains produce different compounds capable of NPs synthesis, only some of which require light activation.55 Another important point related to illumination is the light intensity. Mankad et al reported complete extracellular reduction of silver ions to Ag-NPs after exposure of a mixture of Azadirachta indica leaf extract and silver nitrate solution to sunlight for only 5 min.93

Time of Exposure

The time of reaction varies among different microorganisms, with some able to synthesize NPs within minutes whereas others require weeks. Lengke et al reported that P. boryanum UTEX 485 took 28 days to synthesize Ag-NPs, whereas Zada et al showed that Leptolyngbya sp. JSC-1 fabricated Ag-NPs extracellularly from silver nitrate after 20 min.94,95 A recent study showed that the dispersivity and stability of silver-NPs synthesized using Oscillatoria limnetica changed with increasing time. After 48 h of synthesis, the UV spectrum wavelength value was constant, and after 9 months of incubation, the optical intensity had shifted from 0.71 to 0.599 nm, indicating about the stability of Ag-NPs with low agglomeration.26 The stability of Anabaena-mediated Ag-NPs was evaluated after 6 months of storage by Singh et al.96 The results showed that the Ag-NPs were stable with no change in spectral absorbance, at least in the first 3 months.

pH

El Naggar et al reported that pH significantly affected the size and distribution of Ag-NPs.83 They reported that silver-NPs extracellular synthesis using phycoerythrin was inhibited in acidic media (pH), whereas the reaction was enhanced under alkaline conditions (pH 10). In addition, smaller and more highly dispersed NPs were observed at pH 10, whereas, larger and more aggregated NPs were observed at pH 12.

Temperature

Lengke et al reported the first successful alternative to abiotic chemical approaches for fabricating NPs.97 They screened the ability of P. boryanum UTEX 485 to form extra-, intracellular platinum NPs. The results demonstrated the effects of a variable range of temperatures on NP formation, showing that crystallization and recrystallization of NPs depend on temperature. Decreasing temperature resulted in amorphous distribution, while a crystalline structure was dominant at higher temperatures.

Concentration of Precursors and Natural Reducing Agents

The concentration of bioreductant materials has an important influence on the features of NPs, including shape and size.26 The synthesis of NPs is dose dependent and is also related to the type of algae used.65,67 Hamouda et al showed that increasing the concentration of cyanobacteria Oscillatoria limnetica increased the absorbance of the resulting peaks.26 Moreover, they reported that peaks shifted in position from 420 to 430 nm, accompanied by broadening of peaks, indicating an increase in the size of particles. They also found that the extracellular biofabrication reaction of Ag-NPs was dependent on the dose of silver nitrate. Overall, increasing the concentration of precursor materials resulted in an increased optical intensity recorded by UV spectrophotometry.

Nature of Microorganisms

The nature of microorganisms is related to their biomolecular contents and the types of these molecules, such as polysaccharides, peptides, and pigments.21,87 Thus, different microorganisms vary in their ability to form NPs. Brayner et al screened the reduction activity of three cyanobacteria cultures and observed that the size and shape of NPs varied according to the genus of cyanobacteria used.91 Moreover, different strains from the same species were found to produce NPs with different physicochemical and biological characteristics. Recent studies used different strains from the same Nostoc species, including Nostoc sp. Bahar M,32 Nostoc HKAR-2,98 and Nostoc muscorum NCCU-442,56 resulting in different nanosize ranges (8.5–26.44, 51–100, and 42 nm, respectively) of the resulting Ag-NPs.

Other factors may control NP features, including the microorganisms’ habitats and their ability to eliminate metals from their environment.21 Blue-green algae are distinguished by their ability to accumulate heavy metals from the surrounding environment and degrade these metals into NPs.20 Husain et al showed that 30 cyanobacteria strains isolated from a marine habitat had significant potential to extracellularly reduce silver nitrate to Ag-NPs.56 By contrast, other Eubacteria known to be resistant to heavy metals such as Aphanizomenon sp. could not fabricate Ag-NPs from silver metal under laboratory conditions.55

Cyanobacteria as Biomachinery for NPs Synthesis

The blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) are the only known oxygen-producing prokaryotes. All cyanobacteria are microscopic and widespread in aquatic environments, with some terrestrial species. The aquatic forms mostly occur in fresh water and few are marine.99 Cyanobacteria contain non-membrane-bound organelles including chloroplasts, unstacked thylakoids, phycobiliprotein pigments, and cyanophycean starch and peptidoglycan matrices or walls. In addition, they are a rich source of biomolecules such as proteins, enzymes, antioxidants, vitamins, and polysaccharides.27 Although there have been many reports of biological synthesis with different micro- or macro-organisms, using plants, algae, bacteria, and fungi to obtain NPs of various sizes and shapes, few studies have used cyanobacteria as the biological machinery for NP fabrication.12 Cyanobacteria are considered to be important biofactories that can be used to synthesize NPs by either extracellular or intracellular methods, owing to their ease of culture at ambient temperature and under atmospheric pressure, their high growth rate, the variable biocompounds inside their cells, their capacity to take up heavy metal ions, and the environmental safety of their products.20 Different studies have demonstrated the capacity of different cyanobacterial strains to form different types of NPs, including metallic NPs such as Ag-NPs and Au-NPs, and metal oxide NPs such as ZnO NPs and CuO NPs, as well as other nanomaterials such as Ag-Au nanoalloys and semiconductor NPs such as CdS NPs (Figure 6).2,63,99,100

Silver Nanoparticles (Ag-NPs)

Silver-NPs are the most commonly used MNPs in various fields and can be found in many industrial and medical products including dressings, surgical instruments and masks, detergents, and care products.101,102 Conventionally, Ag-NPs have been fabricated by chemical and physical approaches. Due to the drawbacks of these routes include their high cost, high energy requirements, and toxic byproducts, green synthesis methods have been developed to produce clean NPs and avoid the harmful effects of physicochemical techniques.6,12 For instances, Kim et al mentioned that the injection rate and reaction temperature are crucial factors to synthesize Ag-NPs using polyol process and a modified precursor injection approach.103 They generated spherical Ag-NPs with nanosize of 17 nm at 100 °C. In contrast, many studies using neutral organisms could synthesis Ag-NPs with smallest size ranged from 10, 10–15, 14.9 nm at room temperature.32,91,104 Also, Jin et al synthesized Ag-NPs utilizing photoinduced route.105 They found that Ag-NPs have triangular shape with size range between 30 and 120 nm. The scholars used chemically stabilizing agents such as citrate and poly (styrene sulfonate) to obtain stable Ag-NPs. While Arthrospira maxima SAE and Arthrospira platensis were able to generate triangular Ag-NPs (61 and 46 nm, respectively) at 30 °C for 24 h without needing to any stabilizing agents.56

Ecofriendly synthesis research has expanded rapidly to discover new microbes with hydrolytic capacity to synthesize NPs. Among these biological entities, blue-green algae provide a straightforward route for producing the desired Ag-NPs. Desertifilum IPPAS B-1220 was explored for the fabrication of Ag-NPs for the first time by Hamida et al,31 who extracellularly synthesized Ag-NPs using a cell biomass extract under direct illumination for 24 h at room temperature. The formation of D-SNPs confirmed by UV-absorption peak at 421 nm. XRD diffraction pattern exhibited five 2 θ degree at 29.7, 38.4, 44.6, 64.7and 77.7 indicates the nanocrystallinity of D-SNPs. FTIR data demonstrated different IR peaks at 601.81 cm−1, 1042.35 cm−1, 1626.05 cm−1, 2353.23 cm−1, and 3453.72 cm−1 for D-SNPs. According to dominant FTIR spectra, the scholars reported the main biomolecules responsible for the bioreduction and stabilization processes were proteins and polysaccharides. Also, they found that Desertifilum IPPAS B-1220 sp. could produce spherical silver-NPs with sizes ranging from 4.5 to 26 nm.

Lengke et al used P. boryanum UTEX 485 for the first time for both intracellular and extracellular synthesis of Ag-NPs.106 They found that Ag-NPs have octahedral and spherical shapes with nanosize ranged from 1 to 200 and 10 nm, respectively. EDS and XPS indicated the association of trace of iron, phosphorus, and sulfur with silver nanoparticles. They reported that the biofabrication process of silver nitrate could be linked with metabolic process using nitrate by reducing nitrate to nitrite and ammonium which is fixed as glutamine before cyanobacterial death. However, liberating of organic materials after bacterial death resulted in precipitation of Ag-NPs in solution. A recent study investigated the hydrolytic activity of a new strain of cyanobacteria, Nostoc sp. Bahar M, to extracellularly fabricate silver-NPs from silver nitrate.32 The authors mentioned that the plasmon resonance of Nostoc-mediated silver-NPs was at 403 nm, indicating about the smaller size of these NPs. Also, XRD pattern confirmed the face-centered cubic crystalline structure of silver-NPs. TEM and SEM showed that silver-NP produced by Nostoc sp. Bahar M was uniformly distributed and spherical in shape, with average nanosize of 14.9 nm. Also, FTIR data exhibited that protein molecules play important role in the biofabrication process of Ag-NPs. Recently, an aqueous extract of Oscillatoria limnetica biomass was also used to synthesize Ag-NPs at room temperature for 18 h.26 The Ag-NPs were spherical in shape and have diverse size ranged between 3.30 and 17.97 nm. Also, the authors studied variable abiotic factors such as pH, time, and concentration of natural reducing materials and silver nitrate to determine the optimal conditions for silver-NP synthesis. They found that the most suitable conditions to produce Ag-NPs from Oscillatoria limnetica are at pH of 6.7 and for 18 h as well as the synthesis process is dose-dependent manner for both silver nitrate and cyanobacterial extract concentrations.

Thirty cyanobacterial species were screened for extracellular synthesis of Ag-NPs.56 The results showed that all 30 cyanobacteria were able to form Ag-NPs from their precursor materials, with variable size ranges. Cylindrospermum stagnale performed the best, producing the smallest Ag-NPs with nanosizes of 38–40 nm. Similarly, Sudha et al screened the Ag-NP fabrication ability of several cyanobacteria species isolated from Muthupet mangroves, including Aphanothece, Oscillatoria, Microcoleus, Aphanocapsa, Phormidium, Lyngbya, Gloeocapsa, Spirulina, and Synechococcus.68 Of all the tested microorganisms, only Microcoleus sp. could reduce silver nitrate and form spherical Ag-NPs, with an average diameter of 55 nm.

Patel et al performed both extracellular and intracellular synthesis of Ag-NPs with light and dark incubation using different cyanobacterial isolates, including Anabaena sp., Aphanizomenon sp., Cylindrospermospsis sp. 121–1, Cylindrospermopsis sp. USC CRB3, Lyngbya sp., Limnothrix sp., Synechocystis sp., and Synechococcus sp. With the exception of Aphanizomenon sp., all tested cyanobacteria reduced silver nitrate into Ag-NPs under direct light exposure using either cell-free culture liquids or cell biomass extracts. In addition, only the cell biomass extracts of Anabaena sp., Limnothrix sp., and Synechocystis sp. were able to synthesis Ag-NPs under dark incubation. Only Aphanizomenon sp. failed to tailor the bulk material into its nanoform (Table 2).55

|  |  |  |

Table 2 Cyanobacteria-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) |

Gold Nanoparticles

Au-NPs are known to be good heat conductors and low toxicity NPs against normal cells that are suitable for use in photothermal therapy to treat cancer.107 As well as physiochemical methods, biological synthesis can be used to synthesize Au-NPs in an ecofriendly manner. The first investigation of the ability of Anabaena laxa to catalyze the conversion of hydrogen tetrachloroaurate (III) into Au-NPs was performed by Lenartowicz et al.108 They reported that A. laxa were able to intracellularly fabricate Au-NPs with diverse morphologies and sizes using three different concentrations of auric chloride (HAuCl4; 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mM). The authors reported that the maximum UV spectra peak was formed at 545 and 560 nm for 0.5 and 1 mM of HAuCl4. Three 2θ degree (38.2°, 44.3° and 64.6°) were detected by X-ray diffraction analysis indicating the crystallinity of Au-NPs. Also, TEM micrographs showed that the Au-NPs appearing at 0.5 mM were spherical, however, few NPs with other shapes (triangular, hexagonal, and irregular) were observed. The size of these NPs ranged from 0 to 30 nm; however, the largest particles have size range from 30 to 100 nm. At higher concentration (1 mM of HAuCl4), triangular, hexagonal, and irregular shapes of Au-NPs appeared with nanosize range from 20 to 50 nm. In addition, living cyanobacteria cultures were able to form Au-NPs more efficiently than dead ones, indicating a role of metabolic activity in the bioreduction process of Au-NPs.

Similarly, Dahoumane et al and Brayner et al demonstrated the bioreduction ability of A. flos-aquae to intracellularly synthesize Au-NPs.22,91 Rosken et al showed that A. cylindrica and other Anabaena sp. reduced gold ions to Au-NPs without releasing toxic anatoxin-a.89,109 They mentioned that A. cylindrica were able to intracellularly produce Au-NPs after 4 h under direct illumination incubation. XRD pattern of Au-NPs showed that these NPs have ellipsoidal shape with an aspect ratio of 1.15. The biosynthesized Au-NPs were spherical, and their average size was 10 nm. Moreover, TEM micrographs showed that the Au-NPs mainly distributed in vegetative cells (50%) in comparing with heterocysts and found to be located along the thylakoid membranes. The scholars suggested that heterocysts are not as important for NPs fabrication, due to their results showed that more than 10 vegetative cells contained Au-NPs while only one heterocysts contained NPs. The bioreduction activities of three species of cyanobacteria, Phormidium valderianum, P. tenue, and Microcoleus chthonoplastes, were screened against HAuCl4 solution at different pH values by Parial et al.14 They reported that all three tested cyanobacterial strains were able to synthesis Au-NPs; however, only P. valderianum was able to produce Au-NPs of different shapes and sizes, including nanospheres (15 nm) and triangular (24 nm) and hexagonal (25 nm) NPs, in response to variations in pH. Gloeocapasa sp. were exploited for intracellular synthesis of Au-NPs using cleaned whole cells;110 90 mL of 10−3 HAuCl4 solution was mixed with 10 mL of Gloeocapasa culture and incubated with stirring at ambient temperature. After a few hours, Au-NPs had formed, and their UV absorbance was 547 nm. Moreover, FTIR results showed that algal proteins were responsible for the bioreduction process that formed these NPs, as strong peaks were observed at 3424.96 cm−1, corresponding to N-H stretching, and at 1640.16 cm−1, corresponding to amide I. In addition, SEM and TEM micrographs showed that the Au-NPs had spherical shape and diameters of less than 100 nm (Table 3).

|  |  |

Table 3 Cyanobacteria-Mediated Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles (Au-NPs) |

Other Nanomaterials

The ability of cyanobacteria to reduce metallic NPs is not limited to Ag-NPs and Au-NPs, but extends to other metals including platinum, palladium, and cadmium, as well as metal oxides including copper oxide and zinc oxide. Lengke et al screened the ability of P. boryanum UTEX 485 to form platinum and palladium NPs under variable temperatures.96,111 The scholars mentioned that Pd NPs formed after incubation with P. boryanum for 28 days at 25–100 °C. TEM micrographs of Pd NPs showed that these particles have spherical and elongated shapes, but at 100 °C only spherical palladium hydride appeared. XRD analysis of Pd NPs synthesized at 100°C and 60°C showed different peaks at a Bragg angle (2θ) of 46.9, 54.5, and 81.2 indicates the nanocrystalline of Pd NPs, however, at 25 °C there no diffraction peaks detected. Similarly, different physicochemical analysis of Pt NPs synthesized by P. boryanum UTEX 485 at 25–100 °C for 28 days and at 180 °C for 1 day were performed by Lengke et al XPS results showed the association of sulfur, phosphorus and nitrogen with platinum(II), and EDX analysis indicated the present of sulfur with platinum. So, the authors speculated that these organic elements play significant role in the reduction process of platinum ions into Pt NPs. Brayner et al intracellularly synthesized Au-NPs, Ag-NPs, Pt NPs, and Pd NPs utilizing the biomass of C. pulvinata, A. flos-aquae, and L. foveolarum.91 They suggested that polysaccharides were responsible for NP stabilization.

CdS NPs are well-known and widely studied semiconductors. They have been synthesized using various microorganisms, including yeasts, algae, and fungi.112–114 C-phycoerythrin (CPE) pigment extracted from P. tenue was also used to synthesis 5 nm CdS NPs from their precursors, using an aqueous mixture of CdCl2 and Na2S (Table 4).27 The CdS NPs were formed after incubation with C-phycoerythrin pigment for 24 h at 37 °C. The formation of CdS NPs was confirmed by the absorption peak at 470 nm. FTIR analysis demonstrated new bands at 1543, 1364, 1223 cm−1 appeared only in CPE-coated CdS NPs indicates a new vibration due to C\S band. Other bands seen at 1364 and 1034 cm–1 was related to the C-N stretching vibrations of the aromatic amino amines. Furthermore, EDAX analysis confirmed the existence of both Cd and S in biosynthesized CdS NPs.

|

Table 4 Cyanobacteria-Mediated Synthesis of Other Nanomaterials (NMs) |

Metal Oxides and Akaganéite NPs

Nostoc sp.99 and Anabaena sp.95 have been used to generate ZnO NPs, whereas copper oxide (CuO) NPs were produced by Phormidium cyanobacterium and S. plantensis respectively (Table 4).88,100 Brayner et al synthesized beta-iron oxyhydroxide (β-FeOOH) NPs using A. flos-aquae, C. pulvinata, and Klebsormidium sp.115 They found that there were two basic mechanisms by which iron was acquired higher plants, denoted strategy I and strategy II. Strategy I involves soil acidification and formation of lateral roots and specific transfer cells in the rhizodermis, as well as induction of an Fe3+-chelate reductase and of Fe2+ transporters. This strategy was used in all plants except grasses. Grasses followed strategy II, in which iron is taken up as a Fe3+-siderophore complex. Based on these observations, the authors proposed that the mechanism of iron oxide fabrication by cyanobacteria followed strategy II (siderophore-based iron acquisition). Owing to limited availability of iron, the cells released organic Fe3+ metal-chelating molecules (siderophores) that could solubilize and scavenge iron ions from the environment and internalize them into the cells. Similarly, Dahmoune et al biologically generated akaganeite NPs using A. flos-aquae.116 They showed that XRD analysis of freeze-dried cyanobacteria after reaction with iron salts exhibited the existence of tetragonal akaganeite NPs with some amorphous phase related to the cyanobacteria biomass. TEM ultrathin sections of treated cyanobacteria with iron precursors showed distribution of dark β-FeOOH akaganeite nanorods inside the bacterial cells. However, HR-TEM provided more information about the distribution pattern of akaganeite NPs inside the cells, in which the nanorods appeared as a complex arrangement of pores forming a spongelike structure.

Bimetallic NPs

Bimetallic NPs include a combination of two different metals, the ratio of which can be varied to provide novel physicochemical features derived from the constituting metals (Table 4). 8,12 These NPs are attractive for various applications due to the extra degree of freedom they afford. Govindaraju et al used extracellular synthesis to produce silver-gold core shell NPs, in addition to Ag-NPs and Au-NPs, using single-cell protein S. plantensis.8 The spectral wavelength of silver-gold bimetallic NPs was 509 nm and their size was 17–25 nm. Roychoudhury et al exposed Lyngbya majuscula to an equimolar solution of gold and silver (1 mM, pH 4) for 72 h to produce an Au-Ag nanoalloy.117 They reported that Lyngbya sp. acted as environmentally friendly factories for Au-Ag nanoalloy fabrication. The UV absorbance of the nanoalloy was 481 nm, with a nanosize ranging from 5 to 25 nm.

Applications of NPs Synthesized by Cyanobacteria

Many studies demonstrated the bioactivity of NPs synthesized by different strains of cyanobacteria. These bioactivities are including anticancer, antimicrobial, antioxidant activities (Figure 7).

|

Figure 7 Different applications of NPs synthesized by cyanobacteria. |

Antitumor Activity

Cancer is among the leading causes of death in humans.118 The incidence of cancer is increasing because of various factors, including aging, an increasing population, and lifestyles that predispose to individuals to the disease.118,119 Advances in nanoscience have led to new methods to prevent tumor progression and metastasis.31,32 For example, magnetic iron oxide NPs have improved cellular imaging,13 increasing the quality and speed of diagnostic process. Intravenous injection of Au-NPs can enhance radiotherapy (X-rays), with increased survival of test mice (86%) compared with those treated with X-rays alone (20%).120 There have been many reports of the biological synthesis of NPs using cyanobacteria and their activities against different cancer cell lines (Table 2–4). Green Ag-NPs synthesized by novel Desertifilum sp. induced a drastic loss of viability in HepG2 liver, MCF-7 breast, and Caco-2 colon cancer cell lines, with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 32, 58, and 90 µg/mL, respectively,31 suggested that they may have applications as potent anticancer agents. Bin-Meferij et al reported that Nostoc-mediated silver-NPs (N-SNPs) reduced Caco-2 cell viability by 50%, with an IC50 of 150 µg/mL.32 The authors mentioned that N-SNPs resulted in morphological changes including cell shrinkage, clustering, cell detachment. They speculated that the cytotoxic effect of N-SNPs toward Caco-2 cells resulted from interaction of N-SNPs with different organelles such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum as well as biomolecules such as DNA and proteins. Similarly, a recent study assessed the anticancer activity and biocompatibility of silver-NPs formed by Nostoc sp. against normal and tumor cells.83 Ag-NPs suppressed the proliferation of MCF-7 cancer cells seven-fold compared with normal human lung fibroblast (WI38) and human amnion (WISH) cells. By contrast, the same concentration (13.07 ± 1.1 µg/mL) of a standard antitumor drug, 5-fluorouracil, had a greater cytotoxic effect against WI38 and WISH cells than against malignant cells. Thus, green Ag-NPs appear to be safer to normal cells than 5-fluorouracil. Moreover, the scholars exhibited that after injection of mice bearing Ehrlich ascites carcinoma with 5 mg of Ag-NPs lead to significant reduction in the tumor volume, tumor cells, WBCs count and body weight. Roychoudhury et al found that biosynthesized, ecofriendly, highly stable Ag-NPs showed appreciable antiproliferative effects against leukemic cells, especially the lymphoblastic leukemia (REH) cell line.121 The Ag-NPs (100–1000 µg/mL) showed no effect on peripheral blood mononuclear cells. However, at the same concentrations of Ag-NPs, REH cell line was the most sensitive toward Ag-NPs than other leukemia cell lines including myeloblastic leukemia and lymphoblastic leukemia with IC50 of 620 ± 3.73, 1000 ± 2.79 and 1000 ± 4.38 µg/mL, respectively. Also, the scholars studied the nuclear morphological changes of REH treated with Ag-NPs using DAPI staining assay and observed that Ag-NPs resulted in nuclear damage, shrinkage, chromatin condensation and chromatin margin. A recent publication reported that Anabaena sp. could produce Ag-NPs with strong antitumor activities against Dalton’s lymphoma and colo205 cancer cells.122 They found that low concentration of SNP was able to reduce the proliferation of both cell types via inducting the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and DNA damage led to cell death. The antitumor properties of Ag-NPs biosynthesized by Nostoc sp. HKAR-2 were screened against the MCF-7 cell line.97 The Ag-NPs killed tumor cells effectively as their concentrations increased, suggesting potential applications in the treatment of cancerous cells. Ebadi et al found that a 50 µg/mL concentration of ZnO NPs eliminated 50% of cancerous A549 lung cancer cell line, while the same concentration killed less than 50% of normal (MRC-5) cells.99

Antioxidative Activity

Singh et al tested the toxicity of biogenic ZnO NPs fabricated by cell extracts from Anabaena strain L31 and biogenic ZnO NP–shinorine conjugates in vivo.95 They monitored the formation of ROS using DCFH-DA as a probe. Under a fluorescence microscope, they observed that ROS reached maximum activity 12 h after incubation with ZnO NPs, in contrast to control cells incubated with DCFH-DA alone. By contrast, ROS production decreased in cells spiked with the ZnO NP–shinorine conjugate. The authors suggested that biogenic ZnO NP–shinorine conjugates have antioxidative properties and could be used as non-toxic sunscreen agents. MubarakAli et al showed that Au-NPs synthesized by Phormidium sp. exhibited stronger antioxidant properties than citric acid.2 They also found that increasing the concentration of Au-NPs increase their scavenging activity (Table 3).

Antimicrobial Activity

Antibacterial Activity

NPs are attractive for medical applications due to their high surface area to volume ratio.12 Smaller NPs have a large surface area that increases the interaction between NPs and target bacterial cells.123 Keskin et al reported that Ag-NPs synthesized by Synechococcus sp. have antibacterial properties against various bacterial strains, including Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli, of which B. subtilis was the most sensitive to biogenic Ag-NPs.72

Hamida et al found that 1.54 mg/mL of silver-NPs synthesized from Desertifilum sp. (D-SNPs) had significant antibacterial activity against five strains of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus cereus, B. subtilis, Shigella flexneri, and Salmonella enterica (clinical isolates).31 S. flexneri showed the greatest response to D-SNPs, with an inhibition zone (IZ) diameter of 22.7 ± 0.3. In another recent study, E. coli, Salmonella typhimurium, drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus mutans, and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (clinical isolates) were treated with 1.5 mg/mL of an aqueous solution of silver-NPs synthesized by Desertifilum sp.123 The D-SNPs were more effectual antibacterial agents than silver nitrate against all tested bacteria; MRSA showed the greatest response to D-SNPs, with an IZ of 23.7 ± 0.08. Treating MRSA with D-SNPs also resulted in ultrastructural changes, including bacterial membrane disruption, cytoplasmic lashing, and atrophy of cells leading to bacterial cell death. Also, the authors suggested that the potential mechanism of D-SNPs against MRSA via direct interaction between NPs and biomolecules such as proteins, enzymes, antioxidants and nucleic acids or/and indirect interaction through enhancing the generation of ROS leading to bacterial death. Ag-NPs (5mM) synthesized by phycocyanin extracted from N. linckia showed significant inhibitory activity against various pathogenic bacterial strains, including S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae.69 The highest IZ diameter (10 mm) was observed in both P. aeruginosa and E. coli, while the IZ diameter of S. aureus and K. pneumoniae was (9 mm). The authors reported that Ag-NPs produced by N. linckia has ability to suppress the Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

In a recent study, the inhibitory activity of silver-NPs synthesized utilizing Nostoc sp. (N-SNPs) was assessed against drug-resistant K. pneumoniae.124 The results demonstrated for the first time the relationship between biogenic silver-NPs and genes related to a bacterial secretion system. N-SNPs resulted in downregulation of the hns, hcp-1, VgrG-1, and VgrG-3 genes responsible for inducing the secretion system. Interactions of Au-NPs with Gram-positive organisms (B. subtilis and S. aureus) were investigated using TEM. The TEM micrographs of B. subtilis showed that the Au-NPs damaged the bacterial cell wall, resulting in pits at the exterior of the cell and deformation of the cell membrane, thereby disrupting bacterial functions such as respiration and permeability.125

The antibacterial activity of Ag-NPs produced by Oscillatoria sp. was observed against pathogens E. coli, Klebsiella sp., Salmonella sp., and Pseudomonas sp. using the disc diffusion method. The maximum antibacterial effects were observed against Pseudomonas sp. (15 mm), and a minor antibacterial effect was recorded against E. coli (10 mm), indicating resistance to Ag-NPs.126 Ag-NPs synthesized from Anabaena sp. showed strong antibacterial activity,122 which was tested against three multidrug-resistant bacteria, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and S. aureus, isolated from foot ulcers of diabetic patients. Sonker et al investigated the inhibitory activities of silver-NPs synthesized using a cyanobacterial extract of Nostoc sp. against two plant-pathogenic bacteria, Ralstonia solanacearum and Xanthomonas campestris.97 The result showed that Ag-NPs (5, 10, 15 µg/mL) lead to suppress the growth of two bacterial strains with IZ ranges of 15 ± 4.5, 25 ± 4, 25 ± 5 and 18 ± 1.5, 23 ± 4, 23 ± 10, respectively.

Patel et al found that Ag-NPs synthesized from different species of cyanobacteria had bactericidal activity against Bacillus megaterium, E. coli, B. subtilis, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and Micrococcus luteus.55 They also reported that all tested bacteria showed resistance to Ag-NPs fabricated by Limnothrix sp., while SNP synthesized by Anabaena sp. was the most significant one, with an IZ of 22 mm. Ahmed et al reported that Ag-NPs synthesized from Spirulina sp. and Nostoc sp. suppressed bacterial growth of the tested bacteria (including S. aureus, Staphylococcus epididymis, K. pneumoniae, E. coli and P. aeruginosa) more strongly than silver nitrate,127 and that P. aeruginosa resisted Ag-NPs synthesized by two isolates.

Roychoudhury et al reported that the synthesized nontoxic, highly stable Ag-NPs synthesized by Lyngbya majuscula exhibited significant biocidal activity against P. aeruginosa.121 The authors subjected the P. aeruginosa with 50 µL of different concentration of Ag-NPs including 1, 0.5, and 0.1 mg/mL for 24 h at 37 °C. The maximum IZ (8 mm) was resulted from treating P. aeruginosa with 0.5 mg/mL of Ag-NPs. Another study found that Ag-NPs synthesized by Nostoc sp., Scytonema sp. and Phormidium sp. were potent antibacterial agents against various pathogens including S. aureus, MRSA, P. aeruginosa, E. coli.75 Seventy microliters of the Ag-NPs synthesized by Nostoc sp., Scytonema sp. and Phormidium sp. inhibited the bacterial growth of all previous tested microbes with IZ diameter of (10, 2, 9, 9 mm), (7, 12, 9, 9.5 mm) and (9, 11.5, 8, 10 mm) respectively. Nostoc-mediated ZnO NPs showed antibiofilm activity against P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus. Atomic force microscopic analysis showed that ZnO NPs destroyed the biofilms of the tested bacteria such that they protruded outward or were sunken inwards (Tables 2–4).99

Antialgal Activity

El-Sheekh et al studied the inhibitory activity of Ag-NPs synthesized by S. platensis, Chlorella vulgaris, and Scenedesmus obliquus against Microcystis aeruginosa.129 M. aeruginosa are well known to be harmful microalgal, which secrete toxins that induce liver cancer. The results of this work encouraged the use of Ag-NPs as antialgal agents to reduce the harmful effect of M. aeruginosa. As the concentration of Ag-NPs increased, the viability of Microcystis cells decreased; at 10 mg/L, Ag-NPs caused a 92% reduction of viable cells, compared with a 30% reduction at 1 mg/L (Table 2).

Antifungal Activity

A recent study showed that Ag-NPs produced by Nostoc sp. HKAR-2 resulted in inhibition of Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma harzianum fungal activity with IZ ranges of 3–5 and 4–5, respectively.97 Morsy et al studied the antifungal activity of Ag-NPs synthesized by EPSs of N. commune against different fungal strains infecting seeds of sorghum, maize, soybean, and sesame.92 They sterilized the grain surface with Ag-NPs then grew the seeds in Dichloran chloramphenicol peptone agar at 25 °C by the direct plate method. Complete inhibition of Fusarium nygamai was observed on sorghum grains and soybean seeds with Ag-NP sterilization, compared with 17.24% and 14.63% of total Fusarium and 7.5% and 8.7% of total fungi with NaOCl sterilization, respectively (Table 2).

Photocatalytic Activity

Keskin et al reported that Ag-NPs produced from Synechococcus sp. had photocatalytic activity.72 These Ag-NPs caused photodegradation of methylene blue; after 4 h, the decolorization of the organic pigment reached 18 ± 0.3% for 20 mg L−1 of aqueous dye solution. Similarly, Ag-NPs fabricated by Microchaete sp. NCCU-342 degraded methyl red dye (84.60%) within 2 h more effectively than cyanobacterial extract (49.80%) (Table 2).128

Other Applications

Bakir et al and Younis et al reported that Au-NPs synthesized by L. majuscule have anti-myocardial infarction properties.129,130 They showed that Au-NPs alone or with cyanobacterial extract inhibit the isoproterenol-induced changes in serum cardiac injury markers, ECG, arterial pressure indices, and antioxidant capabilities of the heart. Also, Ag-NPs synthesized by phycobiliproteins extracted from Nostoc sp. showed antihemolytic activity.83 The authors used 2, 2ʹ-azobis (2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) to induce complete erythrocyte hemolysis (100%) of blood extracted from a rat. They mixed the mixture with Ag-NPs and observed that Ag-NPs inhibit hemolytic activity with inhibition of 96.4% (erythrocyte hemolysis was decreased to be 3.6%) which was similar to those caused by vitamin C (96%). Also, the scholars mentioned that the possible mechanism of antihemolytic activity of Ag-NPs is due to Nostoc material (such as amino compounds (-NH2), phenols (Ar-OH)) capped Ag-NPs which have the antihemolytic and antioxidants activity.

MubarakAli et al showed that C-phycoerythrin-CdS NPs could be used as fluorescence probes in biolabeling for ultrasensitive detection of DNA.27 Similarly, Au-NP synthesized by Phormidium willei and Coelastrella sp. was proven to be used as a biolabeling by MubarakAli (Tables 3 and 4).2 The scholars showed that at higher concentration, the green Au-NPs synthesized by Coelastrella sp only were actively binding to DNA.

Killing Strategies of NPs Against Living Cells

The exact killing mechanism of NPs against living cells such as microbial and cancer cells is still under investigation. However, several studies attributed the toxic effect of NPs against cells to two general strategies: (i) indirect influence in which NPs enhancing the production of ROS results in intensive oxidative stress leading to DNA damage, protein degradation, imbalance in enzyme activities resulting in metabolic toxicity and cellular dysfunctions that finally cause cell death;131,132 (ii) direct influence in which NPs directly interact with cellular structures (such as cellular borders and organelles) as well as cellular components (such as proteins, enzymes, antioxidants, nucleic acids, etc.) led to activate cell death pathways (Figure 8).123,133

Oxidative stress is the dominant key of NP-induced cellular injury. Different factors control the oxidative stress-mediated by NPs including acellular factors (such as particle size, concentration and the chemistry of their surface) and cellular responses (such as mitochondrial respiration, NP-cellular interaction and immune cell stimulation) are responsible for ROS-mediated damage. The induction of oxidative stress by NPs is torch bearers for further pathophysiological influences such as genotoxicity, inflammation, proteins denaturation, enzyme and antioxidants dysfunction demonstrated by stimulation of associated cell signaling pathways causing cell death.132

Many scholars reported that NPs stimulate the production of ROS such as superoxide anion (O2∙−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radicals (OH∙), etc.132,134 This abundance of reactive oxygen species have the potentiality to impair the cellular functions causing oxidative stress. It results from the imbalance between ROS production and the capacity of cells to detoxify or repair the damage caused by free radical intermediates.135 For illustration, the decrease in GSH level after exposure the cells to NPs lead to accumulation of ROS causing oxidative stress.124 Similarly, the imbalance in antioxidant enzymes such as GPx,123 superoxide dismutase, catalase, etc., results in oxidative stress causing cellular dysfunction and led to cell death.136 On the other side, other studies suggested that the direct interaction between NPs and cellular targets (such as mitochondrial respiration, metabolism, inflammation, etc.) results in direct induction of oxidative stress.124,132,137

In prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, cellular membranes are the protective barriers against the external stress and controlling the transport of nutrients in/out the cells.37 When NPs injected to the cells, it was observed that these particles attracted to cellular membranes may be due to charge of NPs and their surface chemistry.123,138 This direct interact between NPs and cellular membranes results in irregular, folded, pored membranes and sometimes causes completely lysed membranes affecting the membrane integrity and permeability, causing cell death.138,139 TEM micrographs taken by Hamida et al showed that N-SNPs attached to plasma membranes of MRSA, K. pneumoniae.123,124

After NPs well ingested into cells, result in cytoplasmic dissolution and nuclear damage including nucleoagglomeration, chromatin condensation and DNA damage.133 On the other hand, NPs impaired with biomolecules including enzymes (such as adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) causing metabolic toxicity),123 antioxidants and antioxidant enzymes (such as GSH, GPx result in induction of oxidative stress),124 proteins (such as membrane proteins causing protein denaturation led to influence biological activities),123 nucleic acids (such as DNA causing DNA damage),140,141 enhancing cellular death pathways.

A recent study demonstrated the direct interaction between NPs and cellular organelles such as LDs, endosomes, mitochondria, etc.142 Barkhade et al showed that cells treated with titanium dioxide NPs exhibited swallowing mitochondria and influence the mitochondrial membrane permeability.143 Also, it was found that Au-NPs increase number of mitochondria and decrease the number of lipid droplets indicating that cells produce more energy in trial to remove the stress caused by NPs.142 Furthermore, the high incidence of, autophagic vacuoles, endosomes, cytoplasmic vacuoles were observed after treatment cancer cells with Ag-NPs.142,144 Another study showed that Ag-NPs and copper NPs resulted in increasing lipid droplets that may be return to nanotoxicity that impaired the lipid catabolic activity. The authors reported also that high incidence of peroxisomes as well as lysosomes and low distribution of endoplasmic reticulum indicating necrosis.144

Future Remarks

Green nanotechnology is considered a promising domain of modern science. This technology facilitates the synthesis of NPs by ecofriendly and inexpensive processes, resulting in high yields. Various natural resources are used to biosynthesize NPs, including plants, fungi, bacteria, cyanobacteria, and algae. However, some aspects still require more detailed investigation; for instance, many cyanobacterial strains remain unexplored. Further studies are needed to discover the biocatalytic activities of these cyanobacteria and their abilities to biotransform precursor metals into nanoforms.

Although many hypotheses have been proposed, the exact mechanism of NP synthesis using living organisms has not yet been elucidated. Thus, it will be necessary to further explore how microorganisms synthesize NPs and determine why different strains from the same species result in morphologically diverse NPs. Furthermore, studying the effects of biotic and abiotic conditions such as electrostatic force, metabolic status, growth conditions, and biomolecules (enzymes, pigments, proteins, etc.) on the green fabrication process will enable control of the physicochemical and biological properties of NPs. The emergence of serious diseases that threaten human health will motivate research to screen the activity of green NPs in various medical domains, including developing new antimicrobial and anticancer agents. In this respect, this review recommends that future studies focus on the cyanobacteria-nanotechnology field.

Conclusions

The use of cyanobacteria as bio-fabrication machinery to synthesize NPs has tremendous value, as it enables safe eco-friendly synthesis, as well as being inexpensive and saving energy, and produces novel NPs with varied shape and size. Cyanobacteria-mediated NPs have various biological, physical, and chemical features that provide versatile applicability. Many studies have shown that these NPs can serve as antimicrobial, anticancer, photocatalytic agents, etc. Cyanobacterial strains such as Desertifilum sp. and Nostoc sp. have been screened and used to synthesize Ag-NPs with significant anticancer activity against various cancer cell lines. Furthermore, Ag-NPs and Au-NPs fabricated using Spirulina sp. and Anabaena sp. show broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Development and improvement of biosynthetic processes using cyanobacteria may lead to the discovery of new biogenic NPs with unique properties to serve various needs. Their incorporation into medical treatments could increase efficacy and diminish side effects (Figure 9).

|

Figure 9 The potentiality of cyanobacteria to reduce various shape of NPs with potent biological and chemical applications. |

Highlights

- The use of cyanobacteria as bio-fabrication machinery to synthesize NPs has tremendous value, as it enables safe eco-friendly synthesis, as well as being inexpensive and saving energy, and produces novel NPs with varied shape and size.

- Cyanobacteria-mediated NPs have various biological, physical, and chemical features that provide versatile applicability.

- Development and improvement of biosynthetic processes using cyanobacteria may lead to the discovery of new biogenic NPs with unique properties to serve various needs.

Abbreviations

NPs, nanoparticles; SNPs, silver nanoparticles; AgNO3, silver nitrate; nm, nanometer; min, minute; µL, microliter; mg, milligram; mL, milliliter; µg, microgram; mM, millimolar; h, hour; cm−1, inverse centimeter; rpm, revolutions per minute, SEM, scanning electron microscope; TEM, transmission electron microscope; DLS, dynamic light scattering; FTIR, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy; XRD, X-ray diffraction; kV, kilovolt; kb, kilobase; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; UV-vis, ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy.

Data Sharing Statement

The data supporting this article are available in Figures 1–9 and Tables 1–4. The data sets analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University through the Fast-track Research Funding Program.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Dubchak S, Ogar A, Mietelski J, Turnau K. Influence of silver and titanium nanoparticles on arbuscular mycorrhiza colonization and accumulation of radiocaesium in Helianthus annuus. Spanish J Agri Res. 2010;8(1):103–108. doi:10.5424/sjar/201008S1-1228

2. MubarakAli D, Arunkumar J, Nag KH, et al. Gold nanoparticles from Pro and eukaryotic photosynthetic microorganisms—Comparative studies on synthesis and its application on biolabelling. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;103:166–173. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.10.014

3. He X, Deng H, Hwang H-M. The current application of nanotechnology in food and agriculture. J Food Drug Anal. 2018.

4. Nanotechnology AOo. National Nanotechnology Strategy Annual Report 2008:2007-2008.

5. Roco MC. The Long View of Nanotechnology Development: The National Nanotechnology Initiative at 10 Years. Springer; 2011.

6. Thakkar KN, Mhatre SS, Parikh RY. Biological synthesis of metallic nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2010;6(2):257–262. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2009.07.002

7. Schmid G. Nanoparticles: From Theory to Application. John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

8. Govindaraju K, Basha SK, Kumar VG, Singaravelu G. Silver, gold and bimetallic nanoparticles production using single-cell protein (Spirulina platensis) Geitler. J Mater Sci. 2008;43(15):5115–5122. doi:10.1007/s10853-008-2745-4

9. Durán N, Durán M, De Jesus MB, Seabra AB, Fávaro WJ, Nakazato G. Silver nanoparticles: a new view on mechanistic aspects on antimicrobial activity. Nanomedicine. 2016;12(3):789–799. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2015.11.016

10. Mohamed A, Fouda A, Elgamal M, et al. Enhancing of cotton fabric antibacterial properties by silver nanoparticles synthesized by new Egyptian strain Fusarium keratoplasticum A1-3. Egypt J Chem. 2017;60(ConferenceIssue (The 8th International Conference of The Textile Research Division (ICTRD 2017), National Research Centre, Cairo 12622, Egypt.)):63–71. doi:10.21608/ejchem.2017.1626.1137

11. Bianco A, Kostarelos K, Prato M. Applications of carbon nanotubes in drug delivery. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9(6):674–679. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.10.005

12. Pathak J, Ahmed H, Singh DK, Pandey A, Singh SP, Sinha RP. Recent developments in green synthesis of metal nanoparticles utilizing cyanobacterial cell factories. In: Durgesh KT, editor. Nanomaterials in Plants, Algae and Microorganisms. Elsevier; 2019:237–265.

13. Park JH, von Maltzahn G, Zhang L, et al. Magnetic iron oxide nanoworms for tumor targeting and imaging. Adv Mater. 2008;20(9):1630–1635. doi:10.1002/adma.200800004

14. Parial D, Patra HK, Dasgupta AK, Pal R. Screening of different algae for green synthesis of gold nanoparticles. Eur J Phycol. 2012;47(1):22–29. doi:10.1080/09670262.2011.653406

15. Hassan SE-D, Fouda A, Radwan AA, et al. Endophytic actinomycetes Streptomyces spp mediated biosynthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles as a promising tool for biotechnological applications. JBIC J Biol Inorganic Chem. 2019;24(3):377–393. doi:10.1007/s00775-019-01654-5

16. Fouda A, Saad E, Salem SS, Shaheen TI. In-vitro cytotoxicity, antibacterial, and UV protection properties of the biosynthesized Zinc oxide nanoparticles for medical textile applications. Microb Pathog. 2018;125:252–261. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2018.09.030

17. Salem SS, Fouda MM, Fouda A, et al. Antibacterial, cytotoxicity and larvicidal activity of green synthesized selenium nanoparticles using Penicillium corylophilum. J Cluster Sci. 2020;1–11.

18. Gour A, Jain NK. Advances in green synthesis of nanoparticles. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47(1):844–851. doi:10.1080/21691401.2019.1577878

19. Khanna P, Kaur A, Goyal D. Algae-based metallic nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and applications. J Microbiol Methods. 2019;163:105656. doi:10.1016/j.mimet.2019.105656

20. Sharma A, Sharma S, Sharma K, et al. Algae as crucial organisms in advancing nanotechnology: a systematic review. J Appl Phycol. 2016;28(3):1759–1774. doi:10.1007/s10811-015-0715-1

21. Asmathunisha N, Kathiresan K. A review on biosynthesis of nanoparticles by marine organisms. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;103:283–287. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.10.030

22. Dahoumane SA, Djediat C, Yéprémian C, et al. Species selection for the design of gold nanobioreactor by photosynthetic organisms. J Nanoparticle Res. 2012;14(6):883. doi:10.1007/s11051-012-0883-8

23. Dahoumane SA, Wujcik EK, Jeffryes C. Noble metal, oxide and chalcogenide-based nanomaterials from scalable phototrophic culture systems. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2016;95:13–27. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.06.008

24. Lengke MF, Fleet ME, Southam G. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by filamentous cyanobacteria from a silver (I) nitrate complex. Langmuir. 2007;23(5):2694–2699.

25. Lengke MF, Fleet ME, Southam G. Morphology of gold nanoparticles synthesized by filamentous cyanobacteria from Gold(I)−Thiosulfate and Gold(III)−Chloride complexes. Langmuir. 2006;22(6):2780–2787. doi:10.1021/la052652c

26. Hamouda RA, Hussein MH, Abo-Elmagd RA, Bawazir SS. Synthesis and biological characterization of silver nanoparticles derived from the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria limnetica. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):13071. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49444-y

27. MubarakAli D, Gopinath V, Rameshbabu N, Thajuddin N. Synthesis and characterization of CdS nanoparticles using C-phycoerythrin from the marine cyanobacteria. Mater Lett. 2012;74:8–11. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2012.01.026

28. Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury JB, Herdman M, Stanier RY. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. Microbiology. 1979;111(1):1–61. doi:10.1099/00221287-111-1-1

29. Tyagi R, Kaushik B, Kumar J. Antimicrobial activity of some cyanobacteria. In: Kharwar RN, editor. Microbial Diversity and Biotechnology in Food Security. Springer; 2014:463–470.

30. Mukund S, Sivasubramanian V. Anticancer activity of oscillatoria terebrieormis cyanobacteria in human lung cancer cell line a549. Int J Appl Biol Pharm Technol. 2014;5(2):34–45.

31. Hamida RS, Abdelmeguid NE, Ali MA, Bin-Meferij MM, Khalil MI. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using a novel cyanobacteria desertifilum sp. extract: their antibacterial and cytotoxicity effects. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:49–63. doi:10.2147/IJN.S238575

32. Bin-Meferij MM, Hamida RS. Biofabrication and antitumor activity of silver nanoparticles utilizing novel nostoc sp. Bahar M. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:9019–9029. doi:10.2147/IJN.S230457

33. Ahmad S, Munir S, Zeb N, et al. Green nanotechnology: a review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles—an ecofriendly approach. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:5087. doi:10.2147/IJN.S200254

34. Baker S, Rakshith D, Kavitha KS, et al. Marine microbes: invisible nanofactories. Bioimpacts. 2013;3(3):111–117. doi:10.5681/bi.2013.012