Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 17

COVID-19 Linked Social Stigma Among Arab Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Experiences from the Active Phase of the Pandemic

Authors Madkhali NAB , Ameri A, Al-Naamani ZY, Alshammari B , Madkhali MAB, Jawed A, Alfaifi F, Kappi AA, Haque S

Received 19 November 2023

Accepted for publication 9 February 2024

Published 26 February 2024 Volume 2024:17 Pages 805—823

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S450611

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Norah Abdullah Bazek Madkhali,1 AbdulRahman Ameri,2 Zakariya Yaqoob Al-Naamani,3 Bushra Alshammari,4 Mohammed Abdullah Bazek Madkhali,5 Arshad Jawed,1 Faten Alfaifi,1 Amani Ali Kappi,1 Shafiul Haque6

1Department of Nursing, College of Nursing, Jazan University, Jazan, 45142, Saudi Arabia; 2Mohammed bin Nasser Hospital, MOH, Jazan, Saudi Arabia; 3Armed Forces Medical Services School (AFMSS), Muscat, Oman; 4Department of Medical-Surgical Nursing, College of Nursing, University of Hail, Hail, Saudi Arabia; 5Al Tuwal General Hospital, MOH, Jazan, Saudi Arabia; 6Research and Scientific Studies Unit, College of Nursing, Jazan University, Jazan, 45142, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Norah Abdullah Bazek Madkhali, Department of Nursing, College of Nursing, Jazan University, Jazan, 45142, Saudi Arabia, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Objective: This study aimed to explore the magnitude and variability of the disease-linked stigma among COVID-19 survivors and their experiences of social stigma, coping strategies, contextual challenges, and preferences for support.

Methods: An Arabic version of the social stigma survey questionnaire was designed and validated to obtain socio-demographic characteristics and quantitative measures of stigma encountered by the survivors. 482 COVID-19 survivors completed the survey, and the data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis.

Results: The results of this study revealed the prevalence of high levels of both perceived external stigma and enacted stigma among participants. Enacted and Internalized stigma were associated with survivors’ educational background/ status. The participants suggested three levels of support: organizational, social, and personal. Establishing an online stigma reduction program and national psychological crisis interventions at the organizational level. It is crucial to assist coping mechanisms and societal reintegration techniques at the social level.

Conclusion: These results provide valuable insights for holistic health policy formation and preparedness strategies for future pandemics, helping survivors promote health and reintegrate into society, where stigma reduction and psychological crisis interventions are underdeveloped.

Keywords: COVID-19, survivor, stigma, SARS-CoV-2, pandemic, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by SARS-CoV-2, originated in Wuhan, China, and has triggered huge global attention since December 2019.1 The disease spread quickly across the globe, becoming a pandemic. Saudi Arabia also witnessed a huge surge in COVID-19 cases since January 2020 and reported841469confirmed cases of COVID-19, with 9646 deaths until May 2023.2 Since the first reported case of COVID-19 and the surge from mid-2020 to the fall of 2023, there have still been around 4000 active cases in the country.2 Patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 may develop severe and even fatal acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or acute respiratory failure, leading to their admission into intensive care units (ICUs) in hospitals.3 The horrendous death caused by COVID-19 has resulted in grief, stress, anxiety, depression, and traumatic symptoms for most people, particularly the families of COVID-19-infected patients.3 Moreover, the survivors of this dreaded disease possibly faced discrimination and social stigma owing to the rapid virus spread and unpredictability caused by the pandemic.4 One of the consequences in the context of health was the social stigmatization of people who have been affected by COVID-19. Social stigma is a negative association with a person, group, or location with certain characteristics or a specific disease.5 Such stigma can severely and detrimentally affect survivors’ emotional, mental, and physical well-being. People stigmatized because of infectious diseases may face rejection from partners, families, and friends, as well as dismissal from work and a regression in the quality of healthcare they receive, which can lead to alienation, depression, or anxiety.6 Social stigma leads to prejudice, social exclusion, discrimination, marginalization, and even racism because of negative attitudes and beliefs due to COVID-19.7 Moreover, stigma causes further negative experiences and feelings when sufferers need access to various amenities and healthcare services. As a result, people often feel accused, humiliated, irrelevant, isolated, excluded from society, and discriminated against.8 Prejudice and discrimination, which are undesirable and detrimental for any society, when expressed against those with stigmatizing characteristics, are called Enacted Stigma, while feelings of being accused, humiliated, and irrelevant due to having the stigmatizing characteristic are called Internalized Stigma.9 During the COVID-19 epidemic, women reported increased levels of worry and anxiety as well as more disruptions in their lives than men. The significant consequences of gender disparities in reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic give gender inequality in COVID-19 responses.10 The proportion of women over males was more significant in the areas where the health crisis has had a more noticeable and impactful presence, with implications for the general population, especially women’s physical, mental, and social health.11

Although many studies have reported psychological (anxiety, depression, stress/ distress/ fear) impacts of COVID-19 from around the globe, only scanty studies reported the social stigma among COVID-19 patients and their experiences or coping/ societal re-integration strategies, including Arabian countries. Fortunately, few reports addressed the social stigma prevalent among healthcare workers worldwide, including Saudi Arabia, but none discussed the coping strategies and preferences of support.12–14 The shame and contempt levels caused by contagious diseases are determined by the level of awareness available about the disease and its treatment options currently available.8 The uncertainty and unpredictable course surrounding COVID-19, the perceived risk of contracting the infection, the lack of FDA-approved treatments, the high fatality rate, especially among patients with chronic illnesses, and the novelty (with almost no or limited information about its origin and pathogenicity) of the disease. This caused adverse psychological reactions, including maladaptive behavior, contributing to widespread fear of COVID-19 and avoidance behavior among individuals.12 While the COVID-19 global emergency is officially over,15 the COVID-19 pandemic and its stigmatization will likely continue for many years.16 People were thus likely to be labeled, stereotyped, discriminated against, and treated differently because of an actual or perceived association with the contagious disease. The fear that COVID-19 survivors can transmit SARS-CoV-2 even after hospital discharge primarily constituted the basis of COVID-19-associated stigma.

Keeping the facts above about the dreaded COVID-19 and its impact on the physical and mental health of patients/disease survivors and its societal repercussions in relevance with Saudi Arabia’s traditional living, ethnic/tribal culture, and ardent religious belief in view. This study explored the prevalence of disease-linked stigma, its socio-demographic correlates, and its relationship with the length of time since a patient’s discharge from the hospital among COVID-19 survivors recruited from different regions of Saudi Arabia. The overall aim of this cross-sectional study was divided into four main objectives: (i) to quantify COVID-19-associated stigma experienced by Arab survivors; (ii) to explore the types of stigma(s) encountered by COVID-19 survivors; (iii) to study the influence of ethnic (traditions) / religious culture/beliefs on COVID-19 survivors’ stigma and (iv) to explore the views of Covid-19 survivors about coping strategies, contextual challenges they might face, and preferences for support to re-integrate into their social life.

The study highlights the impact of disease-linked stigma on survivors’ mental health and challenges in reintegration into society. It provides valuable insights for holistic health policy formation and preparedness strategies for future pandemics or crises.

Methodology

Study Design, Participants, and Sample Size

A cross-sectional survey study design was adopted to fulfill this study’s objectives. The study was designed to be investigative and conducted by the College of Nursing, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia, in collaboration with various hospitals and universities of the kingdom. The duration of the study is eleven months, commencing in July 2021. The study recruited patients/survivors 18+ years of age and diagnosed with COVID-19. These COVID-19 survivors were recruited to participate in the study while in the hospital for follow-ups. Before securing their written consent, the participants were informed in person, by phone, or by email about the purpose, scope, and study method. They were informed that they could opt out of the study at any point and ensured their data confidentiality would be maintained at all levels. It was also clarified that no personal information will be collected/revealed. Survivors who had cognitive impairment or refused to participate in the study were excluded from the study. This study did not include patients with chronic tuberculosis or other respiratory illnesses. The eligibility criteria for this study are detailed in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria |

The sample size was determined using the Raosoft online tool17 following a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error, with a target population of 385 required to be statistically significant. The survey questionnaire was developed using Google Forms as an online platform and printed copies in paper hard-copy format to be distributed personally. The standardized instrument (printed copy or online Google form) was distributed by preferred mode, and participants were given sufficient time to complete the survey.

The data for this study were collected from patients admitted to hospitals, healthcare centers, or university hospitals in different kingdom regions. The definition of COVID-19 recovery was taken from the latest guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that state “20 days” have passed from the day symptoms appeared and at least 24 hours have passed since the last fever symptoms were recorded. The inclusion criteria followed for subject recruitment were: (i) individuals (patients) who met the criteria of “recovery”, (ii) attained 18+ years of age, (iii) were able to read/write Arabic or/both English languages. The participants were contacted via telephone, email, or in-person to obtain their consent. Consent terms were also included in the survey questionnaire to inform them of the terms and conditions of participation.

Demographics and Measures

It consisted of demographic questions (n=10) regarding gender, nationality, marital status, age, residence status (rural/urban), educational level, occupation, living status (alone/with family), family member suffering from COVID-19, and income level. The COVID-19 stigma survey includes 15 items that measure the total stigma as enacted stigma, internalized stigma, perceived external stigma, and disclosure fear, which were used in this study.12 The values described the experience of COVID-19 survivors after they recovered or detected negative. Higher scores showed a more significant concern or complicated effect of COVID-19-associated stigma and vice versa. The responses were expressed in terms of ordinal data varying from 1 to 5, wherein (1) represented Strongly Disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Neutral, (4) Agree, and (5) Strongly Agree based on a 5-point Likert scale. The total scores ranged from a minimum of 15 to a maximum of 75; the higher the score, the greater the level of the perceived stigma. The reliability of the questionnaire was ascertained and demonstrated excellent consistency (Cronbach’s α’ = 0.92).

The Arabic version was verified for its translational validity by two native Arabic speakers and then was translated back by two native English speakers. The initial and translated drafts were cross-checked for discrepancies and refined by meeting with all members involved in this research study. A panel of experts from the Nursing College, Jazan University, reviewed and approved the Arabic version. The review included three options (essential, helpful but not essential, and non-essential) against each item in the questionnaire. The outcome was measured using Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio (CVR) for every item and Content Validity Index (CVI).18,19 The items rated “essential” were considered primarily for the calculations. The item details have been presented in Table 2. Open-ended questions (n=3) focused on survivors’ stigmatization experiences and coping strategies, contextual challenges, and preferences for support to re-integrate into their social life.

|

Table 2 Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratios (CVR) for an Item and Content Validity Index (CVI) Value |

Data Gathering

The responses were collected via Google form/ in-person as per the need/feasibility. A team of data collectors was initially trained to collect the data and then sent to the field for the participants needing assistance. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and then a questionnaire was shared.

Statistical Analysis

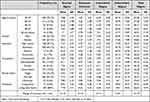

Microsoft Excel was used to enter the data and other associated questions. Categorical values were analyzed for the frequency and the percentages. The questions from Section 2 that measured the disease-related stigma were measured for the aggregate score in terms of mean, frequency, median, and standard deviation for every item and for the domain as a whole. The participant’s data were tabulated using Microsoft Excel and then exported to Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSSTM) version 25 for performing descriptive analysis. The results were reported across the items (Table 3). The principal investigator (NM) used thematic analysis to examine free-text replies to find overarching themes that emerged from the data. After that, other researchers in the team reviewed the themes (BS, ZA, AK).20 Stage one of the study entailed assigning descriptive themes to various data segments. Stage two required combining these descriptive themes to produce interpretative themes that emphasized new patterns in the data (Several overarching themes were established as all interpretive themes were brought together and connected in the final stage.

|

Table 3 Descriptive Analysis of the Data Collected |

Ethical Considerations

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethics approval from the Jazan University Research and Ethics Committee (REC-43/06/126) and the Jazan Health Ethics Committee (H-10-Z-073), MOH, (#2158). During the ethical approval, the study information was provided, including the voluntary nature of the study and the participant’s right to withdraw at any time. Participants’ confidentiality and privacy were maintained throughout the study. Participants’ informed consent included the publication of anonymized information. Written informed consent was obtained before the data collection and responses.

Results

Out of 500 participants, there were 482 COVID-19 survivors (455 Saudi citizens and 27 non-Saudi/ residents). The Arabic version was distributed among the survivors, and their responses were collected. The obtained score distribution is plotted in Figure 1 against every item of the stigma scale.

|

Figure 1 Score distribution to stigma questionnaire by the study participants. |

The data’s internal consistency (ie, reliability) was measured using Cronbach’s alpha, which reflects how closely related the items are as a group. A high value indicates the scales to be unidimensional, and additional analyses can be carried out. The Reliability analysis of the test revealed Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.932. The content validity ratio was calculated using Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio (CVR) for every item and the overall scale’s Content Validity Index (CVI) value.18,19 The formula used for calculating CVR is as follows:

Where ne is the number of panel members rating the item “essential”; N is the total number of members in the panel. The critical values of CVR, if higher than 0.5, are considered acceptable This indicates that more than 50% of the panel members agree that the item is essential. The CVR in our study ranged between 0.6 and 1 for each independent item and indicated that all were valid and useful for further analysis. The CVI was found to be 0.8, signifying that the instrument was statistically competent and valid (Table 2).

Examining the sample characteristics, Shapiro–Wilk’s test (p < 0.05)21,22 and a visual inspection of their histograms, normal Q-Q plots and box plots showed that the total scores were not normally distributed with skewness of 0.455 (SE=0.111) and a kurtosis value of −0.407 (SE= 0.222) (Cramer & Howitt, 2004). The data points were found close to the central line (but not onto it) in the Q-Q plot, indicating that the data were slightly skewed. Therefore, non-parametric methods were selected for further analysis (Figure 2a and b).

|

Figure 2 Distribution of scores (a).Depicted as a histogram (b). Normal Q-Q plot of the total score as against stigma questionnaire. |

Socio-demographic information indicated that the participating COVID-19 survivors mostly belonged to the age group of 18–27 years. Their number was 70% of the subjects recruited (338 out of 482). Of all the survivors, 67% were females, and 33% were males. 84% of the survivors lived with family, and 62% were married. The education level of the COVID-19 survivors was found to be graduation (309 out of 482; 64%). Table 3 summarizes the socio-demographic characteristics of COVID-19 survivors who responded to the survey. While a more significant proportion of the survivors (70.1% approx.) belonged to the 18–27 age group, their percentages steadily declined with the increasing age of survivors from 70.1% to 12.7%, 8.7%, 5.6% and 2.9% for 18–27 years, 28–37 years, 38–47 years, 48–57 years, and 57 years and above, respectively. Approximately two-thirds of the respondents belonged to urban areas, while 33% were from rural areas. The minimum to maximum discharge time from hospitals ranged between 7 to 21 days, with a mean discharge time of 13.2 days. More than half of the survivors were unemployed (54%), and most employed (19.5%) belonged to the government sector. Most COVID-19 survivors (62.2%) were married, 32.2% were singles, and 84% of participants lived with their families. Hence, it can be inferred that the survivors had someone to care for and support them during their hospitalization. The four domains in which the study was divided indicated the highest mean value of Enacted Stigma in females (8.83). The Enacted stigma was higher in survivors with master’s degrees (8.29) and in the age group 38–47 years (8.26). The survivors in the public sector scored more (8.53) than their unemployed counterparts.

The analyses revealed that almost all COVID-19 survivors faced at least one stigma-endorsing response (Table 3). The mean stigma sub-scores were highest for Enacted stigma (mean value of 2.64) with a median of 3 (on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1=Strongly Disagree and 5= Strongly Agree), followed closely by Externalized stigma with a mean score of 2.61 with a median of 3. The disclosure concerns fared much lower at a mean score of 2.32 with a median of 2, while Internalized stigma showed a mean score of 2.08 with a median of 1. Social status and the attitudes of close relatives and friends towards the infection were the causes of great concern to the victims. This could lead to isolation and loneliness in patients who have recovered from COVID-19. The total mean stigma score (Overall score combining all domains) was 37.12, with a standard deviation 15.2 and a median score of 37. The overall distribution of the total scores per domain item is shown in Figure 1.

The survivors experienced a high sub-score(s) in the Internalized stigma, eg, “having had COVID-19 disease makes me feel that I am a terrible person” scored 4.0, closely followed by COVID-19 infection made the survivor think that they were not a good person when compared to those who had never contracted the infection, scored 3.98. Another sub-score, almost equivalent to the previous one, was the belief that the survivors had lost friends due to their COVID-19 infection, scoring 3.94. The sub-section indicating that people were fearful of the person who had contracted COVID-19 infection scored the lowest with a mean score of 2.65. These results indicated significant fear and apprehension from others about contracting COVID-19 infection from the survivors.

The obtained data were analyzed for internal reliability. Cronbach’s Alpha (0.932, N=15) was calculated for reliability statistics and to check the internal consistency and reliability of the data. The mean stigma statistic for all the items under study was 2.477 (1.99–3.34), with an average standard deviation of 1.42. One sample t-test was conducted for each domain, comparing the minimum possible score against every domain, indicating conservatively no stigma (Table 4).

|

Table 4 One-Sample t-Test for Each Domain |

Table 5 represents the responses obtained per item and their respective frequencies and percentages. The Enacted stigma had a mean of 2.64, higher than all the domains, indicating much negative self-perception among COVID-19 survivors. The level of emotional distress and aversion to telling people about the COVID-19 infection, the feeling of being bad because the infection happened, took a prominent position in the responses of the COVID-19 survivors. The median was 3, with quartiles Q1 and Q3 at 1 and 4, respectively. This indicates that the responses were primarily concentrated in the middle of the scale. The Disclosure Concerns domain indicated a mean score of 2.32, with a median of 2, indicating no fear of an infected person being around. The third quartile (Q3) was lower than the previous domain’s (2.32 vs 2.64). Internalized stigma domain performed even lower than Disclosure concerns, indicating that participating survivors were sure that contracting the disease is not very distressful and their rejection will not be significant in society. A lower score for Internalized stigma (Mean: 2.08) indicated that, as humans, we do not accept the negative aspects of a situation internally, which may be far from reality. On the contrary, when we look into the Externalized stigma, which reflects the Internalized stigma, from the external perspective, it scores higher. It reached almost equal to the Enacted stigma domain. The mean for Externalized stigma was 2.61, with a median of 3, and the quartiles (Q1 to Q3) ranged from 1 to 4.

|

Table 5 Descriptive Analysis of the Domain and Corresponding Responses |

The responses from all the domains were further segregated into high-moderate-low perspectives. Table 5 represents the details of the analysis for each domain. The responses were segregated into low and high values, making them dichotomous. The responses reaching a median value of 3 or above were considered high scores, while responses lower than 2.9 were combined as low scores and grouped accordingly. This was further used to perform the Chi-Square test to verify whether the variables under study correlated. Table 6 shows the Chi-square values and the corresponding significant values against the tested variables. The p-value obtained <0.001 was much lower than the critical value of <0.05, indicating that the null hypothesis is rejected and a significant statistical correlation exists between the variables tested. Perceived External Stigma and Enacted Stigma were more significant among participants. They most likely had a negative impact on the mental and emotional health of the survivor to a substantial extent.

|

Table 6 Predictors of COVID-19 Perceived Stigma |

Thematic analysis of the open-ended responses generated three overarching themes (Table 7): Self-coping strategies, Contextual challenges during COVID-19, Preferences for self-coping, and support strategies to promote health and social re-integration. The first overarching theme, Self-coping strategies, captures various beneficial strategies to overcome social stigma, discrimination, and social exclusion and their sequels. Additionally, some participants acknowledged following the COVID-19 protocols only partially or not when infected to avoid being stigmatized and discriminated against. Spiritual practices, faith in Allah (the God), and mindfulness were described as practices related to releasing negative feelings and tolerating the negative attitudes of others. The second overarching theme, Contextual Challenges during COVID-19, provides insight into various factors that picture the contextual challenges that participants face and negatively influence their experiences concerning social stigma, coping strategies, and social reintegration. In addition, it explores the negative impact of media factors and policy conflicts on the participants’ experiences about COVID-19 and how they attach meaning to COVID-19. It also explained how the indirect stigmatization by HCPs and the lack of formal education and healthcare support shape participants’ and community members’ experiences and perceptions in conjunction with how meaning is attached to concepts and attitudes towards them, such as COVID-19 and its protocol and behaviors against it.

|

Table 7 Thematic Analysis of Open-Ended Questions and Free-Text Comments |

The Third overarching theme, Preferences for self-coping and support strategies to promote health and social reintegration, provides evidence from participants on what coping and supporting strategies are essential and how important these strategies are to overcome the barriers of reintegration in society and promote health and psychological well-being. Within the need for future organizational and social interventions, participants highlighted their preferences in initiating future organizational and social interventions that would eliminate discrimination and stigmatization and help enhance the awareness and well-being of infected patients, survivors, and community members. For example, they suggest initiating an official online stigma production program, national psychological crisis intervention, and controlling media outlets at the organizational level. They also suggest establishing peer support groups to help infected people and survivors share their experiences via official media outlets and the COVID-19 stigma campaign. Giving access to psychotherapy, meditation, workout plans, and online applications can help them find emotional healing and cope with their experiences. Thus, they can optimally reintegrate into society when the community members understand and support them. (Figure 3)

|

Figure 3 Preferences stigma interventions for recovery and integrations following the COVID-19 surge. |

Discussion

Although the COVID-19 pandemic’s formal global public emergency is over, its lingering detrimental consequences on people’s physical, mental, and social well-being will probably persist for many years.14,15 By the middle of the pandemic’s fourth year, the new COVID-19 subtypes were still rising.23 WHO’s Technical Advisory Group on SARS-CoV-2 Virus Evolution is still discussing the newest evidence and doing a regular risk assessment of both variants of concern (VOCs) and variants of interest (VOIs),23 in addition to variant under monitoring (VUM).24 A mixed picture is still presented by COVID-19 activity, with the stabilization of intensive care unit admissions and emergency department visits but an increase in outbreaks, primary care positivity, laboratory surveillance test positivity rates, and hospital admissions in the UK.25

Considering the lethal nature of the disease, especially during the active phase, its heavy influence on patients’ physical and mental health, and its societal relevance. This study assesses the prevalence and explores the experiences of social stigma and their preferences for support among COVID-19 survivors. The results obtained from this analysis revealed that almost all the recruited survivors accepted that they experienced at least one stigma. Stigmatizing any disease can harm disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment efforts.26 Several research studies and various organization reports have stated that COVID-19 stigma decreased people’s willingness to seek treatment or have tests done and their adherence to therapies, which resulted in underreporting of the disease.5 Although more than three and half years have passed since the first reported case of SARS-CoV-2, still the disease, COVID-19, is linked with uncertainty and more concerning SARS-CoV-2 variants/OMICRON sub-variants continue to spread widely among people around the world.23,24,27 Even a few countries are still experiencing frequent lockdowns, especially over the winter of 2023, such as China,28,29 North Korea,30 India.31 Gatwick, the second-largest airport in Britain, temporarily suspended daily flights on Sep 2023 due to a staffing deficit in air traffic control due to COVID-19 illness and outbreak.32 Thus, this continuous disease spread partially relates to the stigma associated with uncertainty, fear of the unknown, and difficulty expressing one’s anxieties to others.33

The key findings of this study were the prevalence of high levels of Perceived External Stigma and Enacted Stigma among COVID-19 survivors. These current findings support the findings of Dar et al12 wherein they reported mean stigma sub-scores highest for Perceived External Stigma (15.0), followed closely by Enacted Stigma with a mean score of (7.6) among Indian COVID-19 survivors. A high level of stigma experienced by COVID-19 survivors may be attributed to the attitudes prevalent in the general population,34,35 and we have noticed the same during our study. A national population-based survey study reported that discriminatory tendencies and stigma toward COVID-19 survivors were comparatively high among the general population in Ghana.35 In this study, disclosure concerns performed lower, with a mean score of 3.022, whereas Internalized Stigma had a mean score of 3.4. Stigma brings disgrace and embarrassment,36 which separates COVID-19 survivors from others and significantly increases their suffering. Consistent with previous literature,14,37 this study found that the sufferers often opted to conceal their symptoms, travel histories, or medical histories to avoid prejudice, which might increase the risk of contracting COVID-19. This study also broadly supports that the main reasons for non-disclosure were fear, stigmatization, a lack of public knowledge, and a proper understanding of the disease.38–40 Concealment of COVID-19 symptoms and postponement of seeking healthcare intervention posed further challenges to the public health authorities in their struggle to control the pandemic. It instigated the decision of frontline healthcare professionals to leave their positions against the fear of contracting the infection and passing it on to their families41 and facing the associated stigma with it.42 They were vulnerable because of their traumatic experiences of COVID-19, the terrifying circumstances, and the possibility of dying from the disease.43

The present study concluded that Perceived External Stigma and Enacted Stigma substantially impacted the survivors and influenced their mental and emotional health. Among COVID-19 survivors, their social environment and the attitude of loved ones towards the infection were a cause of considerable concern, leading to their isolation and loneliness. These results concur with previous semi-structured interviews that reported that COVID-19 survivors experienced isolation and labeling in Malaysia.39 The findings also support the previous study that reported COVID-19 survivors (primarily symptomatic patients) experienced high levels of post-traumatic stress and mild depression and anxiety in Pakistan.44

The current study found that survivors recorded high sub-scores in the Internalized Stigma category, which indicated unsurmountable fear and apprehension surrounding survivors related to contracting and suffering from the infection. This fear may be explained by several factors, including uncertainty about the disease, terrifying illness experiences, losing loved ones, and severe family challenges after loved ones die. Yoosefi Lebni et al16 reported that the families of COVID-19 victims encountered various difficulties, such as alienation, limited access to medical care, and disruption in family life. Even after the patient’s death, their challenges continued, including the brevity of the funeral service, the lack of mourners, the incomprehensibility of the death, the sense of guilt, and desertion, all of which made matters worse.16 This study also found that the total stigma was higher in male participants (41.84%) than in females (34.82%). This finding rebutted the previous study10,11 that examined the gender disparities in reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic and showed that women in China and Spain experienced more psychological distress than men during the pandemic. This might relate to the difference in this study setting and the Arab culture and background of the participants.

Findings from this study confirmed the previous systematic review45 but also went beyond that to provide a comprehensive picture of challenges experienced by participants during COVID-19. Participants expressed how social media had shaped negative mental pictures and social attitudes against them and how the COVID-19 news outbreak, misconceptions, rumors, and misinformation impede response efforts by fostering stigma and discrimination. They also explained how some policy conflicts and contradictory information about COVID-19 caused a lack of trust in HCPs, confusion, insecurity, and self-stigma that overwhelmed them physically, mentally, and financially. For example, forcing COVID-19 policies and protocols to follow and associated with crime and significant financial fines. This study also highlighted some HCPs’ behaviors attributed to indirect stigmatization, such as avoidance, ignoring, and sealing patients’ apartments in the context of a lack of psychological health support. All these factors shaped participants’ and community members’ experiences and perceptions in conjunction with how meaning is attached to concepts and attitudes towards them, such as COVID-19 and its protocol and behaviors against it.

This study also found that Internalized Stigma was one of the most profound ramifications of COVID-19, and survivor respondents indicated a significant impact of pandemic-linked stigma. The guilt of being COVID-positive profoundly impacts the person’s overall personality. However, our findings contradicted the previous study that reported low levels of Internalized Stigma among COVID-19 survivors, which suggested higher levels of survivor confidence and self-worth.12 The results showed that Enacted and Internalized Stigma were associated with the participants’ educational levels. Enacted Stigma was comparatively higher in respondents with a higher education level. Higher education is generally linked with more excellent work opportunities, chances of employment, and public engagement, increasing the chances of encountering Enacted Stigma.12 These factors might explain a higher prevalence of Enacted Stigma among well-educated survivors. Looking into the survivors who were employed in any organization scored high on the stigma domain.

In accordance with the present results, previous studies40,46–48 have demonstrated that self-care strategies, including a healthy lifestyle and performing meditation, yoga exercises, and practicing beliefs, were beneficial in coping with social stigma and its sequels. They also discussed various strategies for self-harm reduction, including self-isolation, hiding positive results, controlling thoughts and emotions, and strictly adhering to COVID-19 guidelines and instructions to protect their families and loved ones. The participants in this study also believed that spiritual practice, faith and trust in Allah (the God), self-confidence, and peer support were vital strategies to enhance self-resilience and provide a safe space to express and share concerns. It is significant to identify how to eliminate the stigma associated with health-related concerns such as COVID-19.49

This study also added a novel perspective to international literature by exploring the participants’ preferences for support to combat social stigma and promote health and social reintegration in developing countries where stigma program reduction and psychological healthcare and support are poorly developed. The participants preferred to receive support and suggested interventions at three interconnected levels: organizational, social, and personal (Figure 3). At the organizational level, they suggest establishing an official online stigma reduction program and national psychological crisis interventions in addition to controlling national media outlets to reduce the spread of misinformation and increase public awareness. These strategies are needed to help local society understand the negative impact of COVID-19 stigma and discrimination and equip institutions to help employees and students. At the social level, they suggest various strategies, including allowing the sufferers to express negative feelings, issues, and needs via official media outlets and the COVID-19 Stigma campaign. They also suggested establishing peer support groups and supporting them in finding emotional healing via therapy, mindfulness, or exercise. Thus, the sufferers at the personal level could find, recognize, and implement self-help interventions, have more self-confidence and resilience to overcome social stigma and its sequels, and reintegrate into society.

Many questions remain about the future of the pandemic. The number of reported COVID-19 cases globally may be significantly underestimated, as at-home testing has become more prevalent, and many infections have yet to be reported.50,51 Furthermore, COVID-19 cases have started to rise again in 2023. For example, there were almost 3 million new cases and 23,000 deaths in March, while there were almost 2.8 million new cases and 17,000 deaths in April globally.52,53 Indeed, almost every nation confirmed the coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) in May 2023 and increased deaths, especially in Africa, the Americas, Southeast Asia, and the Western Pacific Region.54,55 The virus has infected over 766 million people worldwide, with nearly 6.9 million deaths, and the US, India, and Brazil are most severely affected.54,55 Such increasing cases again remind us to be aware of the situation in advance and develop psychological coping strategies and healthcare preparedness. This study is still relevant as the findings offer a solid basis for recommending targeted coping/ societal re-integration strategies, including customized social media-based friends’ groups/ systematic learning programs/ online educational forums/ health and mental well-being awareness programs /social media-based audio/video channels/ contents. That can help minimize the pandemic-linked stigma and contribute to developing a knowledge-based society capable of addressing crises.

The effects of COVID-19 stigma will be unexpectedly very long-lasting due to its continuity in terms of the arrival of its variants/ sub-variants, making it difficult for survivors who have recovered from COVID-19 to reintegrate into society and regain self-confidence and trust in others. To the best of our information, this is the very first study reporting the COVID-19-linked stigma from the active phase of the pandemic among COVID-19 survivors and exploring their coping strategies, challenges, and support preferences in reintegration into Saudi society. The relevance of this study has become more significant regarding the central role of traditional Saudi society’s tribal culture and practicing religious beliefs and the prevalence of stigma among disease survivors.

Limitations

The present study employed a cross-sectional research design and provided a snapshot of the existing COVID-19 situation. Therefore, we cannot derive a long-term effect from employing the variables under the current situation. The levels of stigma also slowly diluted, and the acceptance of COVID-19 survivors returned to normal. The current findings only apply to COVID-19 survivors residing in Saudi Arabia as non-Saudi participants only 19 (3.9%); thus, it cannot be generalized to all other Arab countries. Purposive sampling might be used to recruit the subjects best suited for the current study and should not be used to estimate generalizability. During the survey, most participants belonged to urban areas, and survivors from rural areas might have varied experiences. The mean time for the discharge from the hospital for the subjects under study was 13.7 days when stigmatization was greatest and may over-represent the stigma.

Recommendations

Well-designed large-scale prospective research is required to gain a deeper understanding of how stigma can change over time. Comprehensive, in-depth knowledge to understand the factors affecting stigma among COVID-19 survivors can be well elicited through qualitative studies. Although Saudi people are content to accept that COVID-19 is Allah’s will, they are struggling to reintegrate into society. Future stigma awareness programs targeting the consequences of stigmatizing infectious diseases are warranted to address such crises.

Conclusions

High levels of Perceived External Stigma and Enacted Stigma existed among Saudi COVID-19 survivors. Enacted Stigma and Internalized Stigma were both associated with the educational levels of the disease survivors. There is a dire need to develop targeted approaches for preventing and minimizing stigmatization during and after pandemic outbreaks to provide evidence to assist the preparedness for future outbreaks and pandemics of infectious disease. The high score for Enacted Stigma and Externalized Stigma indicated the need for consultation and counseling for the COVID-19 survivors in close collaboration with the medical /emergency services in hospitals and during the post-recovery visits. The study also warrants community services and public awareness to help COVID-19 survivors cope with the stigma, destigmatize it, and assist in quick recovery. It also suggested three levels of support: organizational, social, and personal. Establishing an online stigma reduction program and national psychological crisis interventions at the organizational level. It is crucial to assist coping mechanisms and societal reintegration techniques at the social level, such as specialized social media peer support groups, systematic learning programs, online discussion forums, health and mental health awareness campaigns, and social media-based audio and video channels. These would allow sufferers to express negative feelings, find self-emotional healing, implement self-help interventions, overcome social stigma and its sequels, and optimally reintegrate into society. This study provides valuable insights for holistic health policy formation and preparedness strategies for future pandemics, helping survivors promote health and reintegrate into society, where stigma reduction and psychological crisis interventions are underdeveloped.

Data Sharing Statement

The author makes the data supporting this study’s findings available upon any reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ team would like to thank the health and educational institutions involved in this study for their support in completing this work. In addition, the authors wish to thank the study participants, their relatives, and nursing staff for their willingness and motivation, which made this study possible.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests in this work.

References

1. Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J med virol. 2020;92(4):401–402. doi:10.1002/jmv.25678

2. Saudi MOH Coronavirus dashboard; 2023. Available from: https://covid19.moh.gov.sa/.

3. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

4. CDC (2020). Grief and Loss. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/stress-coping/grief-loss.html.

5. UNICEF, WHO, IFRC 2020. Social Stigma associated with COVID-19 (2020): a guide to preventing and addressing social stigma. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/documents/social-stigma-associated-coronavirus-disease-covid-19.

6. Kane JC, Elafros MA, Murray SM, et al. A scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes for high-burden diseases in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):1–40. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1250-8

7. Siu JYM. The SARS-associated stigma of SARS victims in the post-SARS era of Hong Kong. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(6):729–738. doi:10.1177/1049732308318372

8. Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. J Health Psychol. 2012;17(2):157–168. doi:10.1177/1359105311414952

9. Scambler G. Re-framing stigma: felt and enacted stigma and challenges to the sociology of chronic and disabling conditions. Soc Theory Health. 2004;2(1):29–46. doi:10.1057/palgrave.sth.8700012

10. Ding Y, Yang J, Ji T, Guo Y. Women suffered more emotional and life distress than men during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of pathogen disgust sensitivity. International. J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8539. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168539

11. Iglesias Martínez E, Roces García J, Jiménez Arberas E, Llosa JA. Difference between Impacts of COVID-19 on women and men’s psychological, social, vulnerable work situations, and economic well-being. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8849. doi:10.3390/ijerph19148849

12. Dar SA, Khurshid SQ, Wani ZA, et al. Stigma in coronavirus disease-19 survivors in Kashmir, India: a cross-sectional exploratory study. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0240152. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244715

13. Al-Ghuraibi MA, Aldossry TM. Social Stigma as an outcome of the cultural repercussions toward COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. Cogent Soc Sci. 2022;8(1):2053270. doi:10.1080/23311886.2022.2053270

14. Rewerska-Juśko M, Rejdak K. Social stigma of patients suffering from COVID-19: challenges for health care system. Healthcare. 2022;10(2):292. doi:10.3390/healthcare10020292

15. World Health Organization (2023a). Statement on the fifteenth meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 pandemic. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic.

16. Yoosefi Lebni YJ, Irandoost SF, Safari H, et al. Lived experiences and challenges of the families of COVID-19 victims: a qualitative phenomenological study in Tehran, Iran. Inquiry. 2022;26(59):00469580221081405. doi:10.1177/00469580221081405

17. Raosoft (2004). Raosoft sample size calculator. Seattle: Raosoft, Inc. Available from: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html.

18. Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychol. 1975;28:563–575. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x

19. Ayre C, Scally AJ. Critical values for Lawshe’s content validity ratio: revisiting the original methods of calculation. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2014;47(1):79–86. doi:10.1177/0748175613513808

20. King N, Brooks J. Thematic analysis in organisational research. In: The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: Methods and Challenges. SAGE; 2018:219–236.

21. Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika. 1965;52:591–611. doi:10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591

22. Razali NM, Wah YB. Power comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling tests. J Statisl Mod Anlyt. 2011;2:21–33.

23. World Health Organization (2023b). Updated working definitions and primary actions for SARS-CoV-2 variants, 15 March 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/updated-working-definitions-and-primary-actions-for--sars-cov-2-variants.

24. World Health Organization (2023c). EG.5 Initial Risk Evaluation, 9 August 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/09082023eg.5_ire_final.pdf.

25. UK Health Security Agency (2023). National Influenza and COVID-19 surveillance report Week 37 report (up to week 36 data) 14 September 2023 Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6502fdeb97d3960014482ec8/Weekly-flu-and-covid-19-surveillance-report-week-37.pdf.

26. Fischer LS, Mansergh G, Lynch J, Santibanez S. Addressing disease-related stigma during infectious disease outbreaks. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019;13(5–6):989–994. doi:10.1017/dmp.2018.157

27. Wang C, Han J. Will the COVID-19 pandemic end with the delta and omicron variants? Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022;20:2215–2225. doi:10.1007/s10311-021-01369-7

28. Bloomberg. Chinese City backs return of lockdowns — for Flu; 2023. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-09/chinese-city-backs-return-of-lockdowns-for-severe-flu-outbreaks#xj4y7vzkg.

29. CNN (2023). Chinese city proposes lockdowns for flu – and faces a backlash. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/03/11/china/china-xian-flu-lockdown-intl-hnk/index.html.

30. REUTERS (2023a). North Korea orders lockdown in capital Pyongyang after respiratory illness outbreak. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/east-asia/article/3207914/north-korea-orders-lockdown-capital-pyongyang-after-respiratory-illness-outbreak.

31. KSEDUpdates. When will be lockdown 2023 in India state wise latest news updates covid-19 lockdown status check today; 2023. Available from: https://karnatakastateopenuniversity.in/when-will-be-lockdown.html.

32. REUTERS (2023b). UK’s Gatwick limits flights after illnesses cause staff shortages. Available from: https://www.REUTERS.com/world/uk/uks-gatwick-limits-flights-after-illnesses-cause-staff-shortages-2023-09-25/.

33. Shahnawaz M, Nabi W, Nabi S, et al. Relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and symptom severity in Covid-19 patients: the mediating role of illness perception and Covid-19 fear. Curr Psychol. 2022;11:1–8. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03577-y

34. Chandran N, Vinuprasad VG, Sreedevi C, Sathiadevan S, Deepak KS. Covid-19-related stigma among the affected individuals: a cross-sectional study from Kerala, India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2022;44(3):279–284. doi:10.1177/02537176221086983

35. Osei E, Amu H, Appiah PK, et al. Stigma and discrimination tendencies towards COVID-19 survivors: evidence from a nationwide population-based survey in Ghana. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2(6):e0000307. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0000307

36. Pescosolido BA. The public stigma of mental illness: what do we think; what do we know; what can we prove? J Health Social Behav. 2013;54(1):1–2110.1177/0022146512471197.

37. Mistry SK, Ali ARM, Yadav UN, et al. Stigma toward people with COVID-19 among Bangladeshi older adults. Front Public Health. 2022;2919. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.982095

38. Atinga RA, Alhassan NMI, Ayawine A. Recovered but constrained: narratives of Ghanaian COVID-19 survivors experiences and coping pathways of stigma, discrimination, social exclusion and their sequels. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(9):1801–181310.34172/ijhpm.2021.81.

39. Chew CC, Lim XJ, Chang CT, Rajan P, Nasir N, Low WY. Experiences of social stigma among patients tested positive for COVID-19 and their family members: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-153721/v1

40. Peters L, Burkert S, Brenner C, Grüner B. Experienced stigma and applied coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: a mixed-methods study. BMJ open. 2022;12(8):e0594. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059472

41. Kumar J, Katto MS, Siddiqui AA, et al. Predictive factors associated with fear faced by healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: a questionnaire-based study. Cureus. 2020;14(8):12. doi:10.7759/cureus.9741

42. Nashwan AJ, Valdez GF, Sadeq AF, et al. Stigma towards health care providers taking care of COVID-19 patients: a multi-country study. Heliyon. 2022;8(4):e09300. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09300

43. Davis S, Samudra M, Dhamija S, Chaudhury S, Saldanha D. Stigma associated with COVID-19. Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30(1):S270. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.328827

44. Jafri MR, Zaheer A, Fatima S, Saleem T, Sohail A. Mental health status of COVID-19 survivors: a cross-sectional study. Virol J. 2022;19(1):1–5. doi:10.1186/s12985-021-01729-3

45. Zhou X, Chen C, Yao Y, Xia J, Cao L, Qin X. The scar that takes time to heal: a systematic review of COVID-19-related stigma targets, antecedents, and outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022;13:1026712. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1026712

46. Coppi F, Farinetti A, Stefanelli C, Mattioli AV. Changes in food during Covid-19 pandemic: the different role of stress and depression in women and men. Nutrition. 2023;108:111981. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2023.111981

47. Adom D, Mensah JA, Osei M. The psychological distress and mental health disorders from COVID-19 stigmatization in Ghana. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2021;4(1):100186. doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100186

48. Fatima B, Yavuz M, Ur Rahman M, Althobaiti A, Althobaiti S. Predictive modeling and control strategies for the transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Mathematical Comput Appl. 2023;28(5):98. doi:10.3390/mca28050098

49. Lin JL, Wang YK. Lessons from the stigma of COVID-19 survivors: a Marxist criticism appraisal. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1156240. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1156240

50. Park S, Marcus GM, Olgin JE, et al. Unreported SARS-CoV-2 home testing and test positivity. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6(1):e2252684–e2252684. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.52684

51. Del Rio C, Malani PN. COVID-19 in 2022—The beginning of the end or the end of the beginning? JAMA. 2022;327(24):2389–2390. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.9655

52. World Health Organization (2023d). Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 13 April 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---13-april-2023.

53. World Health Organization (2023e). Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 4 May 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---4-may-2023.

54. Statista (2023). Number of coronavirus (COVID-19) cases worldwide as of May 2, 2023, by country or territory. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1043366/novel-coronavirus-2019ncov-cases-worldwide-by-country/.

55. World Health Organization (2023f). Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 25 May 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---25-may-2023.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.