Back to Journals » Infection and Drug Resistance » Volume 15

COVID-19 Case Fatality Rate and Factors Contributing to Mortality in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence

Authors Girma D , Dejene H , Adugna L , Tesema M, Awol M

Received 3 April 2022

Accepted for publication 29 June 2022

Published 4 July 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 3491—3501

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S369266

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Suresh Antony

Derara Girma,1 Hiwot Dejene,1 Leta Adugna,1 Mengistu Tesema,1 Mukemil Awol2

1Public Health Department, College of Health Sciences, Salale University, Fitche, Ethiopia; 2Department of Midwifery, College of Health Sciences, Salale University, Fiche, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Derara Girma, Email [email protected]

Background: The ongoing novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is triggering significant morbidity and mortality due to its contagious nature and absence of definitive management. In Ethiopia, despite a number of primary studies have been conducted to estimate the case fatality rate (CFR) of COVID-19, no review study has attempted to summarize the findings to better understand the nature of pandemics and the virulence of the disease.

Objective: To summarize the CFR of COVID-19 and factors contributing to mortality in Ethiopia.

Methods: PRISMA guideline was followed. PubMed, Science Direct, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Hinari, and Google Scholar were systematically searched using pre-specified keywords. Observational studies ie, cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control studies were included. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale adapted for observational studies was used to assess the quality of included studies. CFR was defined as the proportion of COVID-19 cases with the outcome of death within a given period. Factors contributing to COVID-19 mortality at p-value < 0.05 were described narratively from the eligible articles.

Results: A total of 13 observational studies were included in this study. Consequently, this review confirmed the CFR of COVID-19 in Ethiopia ranges between 1– 20%. Additionally, comorbid conditions, older age group, male sex, substance use, clinical manifestations (abnormal oxygen saturation level, atypical lymphocyte count, fever, and shortness of breath), disease severity, and history of surgery/trauma increased the likelihood of death from COVID-19 death.

Conclusion: This study shows that the range of CFR of COVID-19 in Ethiopia is almost equivalent to other countries, despite the country’s low testing capacity and case detection rate in reference to its total population. Comorbid diseases, older age group, male sex, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, clinical manifestations and disease severity, and history of surgery/trauma were factors contributing to COVID-19 mortality in Ethiopia. Therefore, given the alarming global situation and rapidly evolving large-scale pandemics, urgent interdisciplinary interventions should be implemented in those vulnerable groups to lessen the risk of mortality. Furthermore, the CFR of COVID-19 should be estimated from all treatment and rehabilitation centers in the country, as underestimation could be linked to a lack of preparedness and mitigation. A large set of prospective studies are also compulsory to better understand the CFR of COVID-19 in Ethiopia.

Keywords: case fatality rate, COVID-19, coronavirus, mortality, Ethiopia

Introduction

The recently emerged novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which spreads in small liquid particles from an infected person’s mouth or nose when they cough, sneeze, speak, sing, or breathe.1 Currently, the ongoing COVID-19 infection was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020,2 following the first case reported in Wuhan City, China, in December 2019.3 Since then, there have been more than 474 million confirmed COVID-19 cases worldwide, with about 6 million deaths as of March 24, 2022.4

COVID-19 causes clusters of fatal pneumonia.5 Thrombosis and pulmonary embolism have also been reported in severe cases.6 Additionally, lung abnormalities, neurological complications, and workout intolerance are commonly noted complications among survivors.7 Patients die due to multiple organ failure, shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, heart failure, anemia, arrhythmias, secondary infection, and renal failure.5,8 Additionally, male sex, older age, history of obesity, hypertension, diabetes,9 and immunosuppression (opportunistic infection)9,10 were associated with an increased risk of hospitalization/death.

Despite those complications – as mitigating activities –keeping social distance and lockdown,6 staying at home and restricting travel,11 wearing a properly fitted face mask, and cleaning hands frequently with sanitizer or soap and water12 have been implemented to alleviate the further spread of the virus. Besides, early diagnosis, immediate isolation, general and optimized supportive care, and infection prevention and control were identified as significant aspects of COVID-19 management.13 Furthermore, getting vaccinated has been stated as an additional action to circumvent the burden of COVID-19. Thus, a total of more than 10.9 billion vaccine doses had been administered as of March 17, 2022.4

On the other hand, even though several options are being implemented to combat this pandemic, its global impact is still uncertain.14 Viral mutation,15 the emergence of new variants and resistance, and unclear routes of transmission16 are the major challenges the health system is facing to control the pandemic. The difficulties in accessing oxygen, medication, vaccination, and medical devices pose an additional threat to developing countries ability to control the pandemic.16

In Ethiopia, the Federal Ministry of Health has confirmed the first COVID-19 case on March 13th.17 As of March 24, 2022, the country tested more than 4 million suspects, which is below 4% of the country’s population,18,19 of whom 469,523 (10.16%) cases had been confirmed positive and of these, 7491 (1.6%) died, 429,269 (91.4%) recovered, and 32,784 (7%) currently infected.19 Besides, the actual number of cases is likely to be much higher than the number of confirmed cases due to limited testing capability and challenges in the attribution of the cause of death.20

The Federal Government of Ethiopia took numerous progressive activities to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. These include; public gatherings suspension, transports restriction, flight suspension, land borders closed, an apology for prisoners, election postponed, state of emergency stated, political parties and religious leaders participated, media informed the public, international alliances allied, and consistent information spreading.21 Furthermore, as of March 17, 2022, Ethiopia had administered more than 29 million doses of the COVID-19 vaccine as a prevention strategy.18

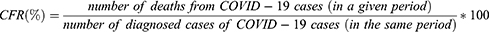

The CFR is one of the most important parameters for understanding the epidemiological features of an outbreak. The CFR of COVID-19 is defined as the number of deaths in COVID-19 cases divided by the total number of people infected by COVID-19.22 This rate is used in describing the mortality process and its overall changes, deciding on health priorities, allocating resources, designing intervention programs, and evaluating and refining problems and programs related to public health and disease epidemics.23

As the threat of COVID-19 persisted, one of the issues that needed to be addressed is identifying the CFR and the key factors contributing to mortality. In Ethiopia, despite a number of primary studies have been conducted to estimate the CFR of COVID-19, no review study has attempted to summarize this evidence to better understand the nature of an outbreak and the virulence of the disease. Therefore, it is critical to summarize and uncover discrepancies in the primary results. The finding of this study is essential for preventing further COVID-19 mortality by identifying and enabling action on the summarized factors that contribute to mortality.

Methods

Search Strategy

This review was conducted to summarize the CFR of COVID-19 and factors contributing to mortality from primary studies done in Ethiopia. As a result, different electronic databases such as PubMed, Science Direct, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Hinari, and Google Scholar were systematically searched. Additionally, other sources such as GOOGLE, journal homepages, and bibliographies were searched to retrieve eligible studies. The search terms were used as keywords and MeSH terms both individually and in conjunction with the “OR” and “AND” Boolean operators. Thus, (“COVID-19”[Mesh] OR “SARS-CoV-2”[Mesh] OR “Corona virus”[tw] OR “COVID-19 positive”[tw] OR “COVID-19 patient*”[tw]) AND (Mortality[tw] OR “Treatment Outcome”[tw] OR fatality[tw] OR Survival[tw] OR “factors associated”[tw] OR predictor OR “Risk Factors”[Mesh]) AND (Ethiopia*[tw]) were used. The Mendeley software was used to save and remove the duplicated record search results.

Eligibility Criteria

Study design: observational studies that have reported CFR of COVID-19 and/or factors contributing to mortality among

COVID-19 patients.

Language: Articles published in the English language.

Publication date: From 2020 to 2022. [accessible before May 01, 2022].

Types of articles: Only full-text articles were included.

Setting: Studies conducted in Ethiopia.

Study Selection, Extraction, and Quality Assessment

Prior to data abstraction, the extraction format was prepared. The data extraction template includes the author’s name, year of publication, study design, study area, source of data, sample size, and outcomes reported relevant to the current review. Full copies of articles identified by the search and meeting the inclusion criteria based on the title, abstract, and text contents are obtained for data synthesis. Two reviewers (DG and LA) – independently assessed studies for potential relevance, applied the eligibility criteria to the results – and did quality assessment independently for the included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality assessment scale adapted for observational studies24 (Table 1). Any disagreements in the evaluation of studies were resolved through consensus among the authors.

|

Table 1 The Newcastle Ottawa Scale Quality Assessment Results of the Included Studies |

The Synthesis

The systematic review approach was used to synthesize the evidence from the included studies. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline was followed to screen the studies.

Review Question

- What is the range of COVID-19 CFR in Ethiopia?

- What are the contributing factors to mortality among COVID-19 patients in Ethiopia?

Case Fatality Rate (CFR) Calculation

In this review, CFR was defined as the proportion of COVID-19 cases with the outcome of death within a given period and calculated as follows.

Contributing Factors

In this review, they are explanatory variables that have been reported to heighten the risk of mortality from COVID-19 infection in selected studies with a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Description of the Searching and Screening Results

A total of 793 records were retrieved through electronic databases search and other sources, and 560 records were removed due to duplication. Then, of the 233 original articles identified, 190 were removed because of irrelevant titles, abstracts, and texts. For the full-text review, 43 articles were selected, of which 30 articles were removed due to the inapt study place and pre-specified criteria. Finally, 13 studies were considered in the study (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 PRISMA flow chart of the included study. Notes: Adapted from: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71.56 Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode). |

Characteristics of the Included Studies

A total of thirteen studies25–37 were included in the review. All studies had been published between 2020 and 2022 with sample sizes ranging from 33 to 4398. Four studies were done in Addis Ababa,26,28,33,35 three were in Oromia region,29,36,37 two were in Amhara region,27,31 one study was in Benishangul-Gumuz region,30 one study was in Harari region,34 one study was in Tigray region,32 and one study was at national level.25 Besides, study design included was one case-control,26 six cohorts,28–30,32–34 and six cross-sectionals.25,27,31,35–37 Moreover, from the encompassed studies, seven reported on both case fatality rate and factors contributing to COVID-19 mortality,28,30–34,37 whereas, five reported only a case fatality rate,25,27,29,35,36 and one reported only on factors contributing to COVID-19 mortality,26 and (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Characteristics of the Included Studies |

The Proportion of Case Fatality Rate

Of the eligible studies, only one study did not report the proportion of CFR due to the nature of the study design.26 However, all the other included studies have reported the CFR.25,27–37 Accordingly, the present study confirmed the CFR of COVID-19 in Ethiopia ranges from nearly 1–20% (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Proportion of COVID-19 Case Fatality Rate |

Factors Contributing to Mortality Among COVID-19 Patients

In this review, of the total included studies, eight reported the factors contributing to mortality from COVID-19 in the Ethiopian population.26,28,30–34,37 As a result, we found that the presence of a high rate of one or more comorbid conditions was significantly associated with COVID-19 mortality and/or poor treatment outcome.26,28,30,32–34,37 Furthermore, non-modifiable risk factors such as sex (being male)30 and older age group30–33,37 were among the factor contributing to mortality from COVID-19 disease. Additionally, behavioral risk factors such as smoking34 and alcohol drinking history34 were found to heighten mortality among confirmed COVID-19 patients in Ethiopia. As well, clinical manifestations and disease severity factors such as oxygen saturation level,28,34 lymphocyte count,33,34 worsening conditions,37 abnormal sodium level,33 shortness of breath,26,28 and fever26 were also identified to increase the likelihood of death from COVID-19 disease. Another important finding was that having a history of surgery/trauma32 increases the chance of mortality among confirmed COVID-19 patients in the country (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Factors Contributing to COVID-19 Mortality in Ethiopia at p-value <0.05 |

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed the available literature to identify the CFR of COVID-19 and factors contributing to mortality in Ethiopia. Thus, based on 13 studies that fulfilled eligibility criteria, the CFR of COVID-19 in Ethiopia ranges from nearly 1–20% among case-confirmed patients. Subsequently, despite the existence of limited evidence on COVID-19 CFR, some primary studies have reported CFR in different settings with various populations. For instance, a study reported from the Tigray region showed a 0.8% CFR among quarantined patients,32 while a study from Addis Ababa stated a 5.3% CFR among prospectively admitted patients.28 Additionally, surveillance data from the Oromia region revealed 1.2% CFR among all case-confirmed individuals.36 In contrast to earlier findings, a high CFR of 20.2% and 19.0% were reported in Benishangul-Gumuz30 and Harari34 regions from retrospective medical record reviews, respectively. These inconsistencies might be due to case/death findings and reporting capacity,38,39 and differences in healthcare practice and preventive strategies.39,40 Furthermore, variation in CFR will be attributed to outcome ascertainment procedures, patient recruitment techniques, eligibility criteria, region location, and access to information.

This study suggests that COVID-19 mortality and/or poor treatment outcome were high among patients with one or more comorbid conditions like diabetes, Asthma, COPD, hypertension, malignancy, CKD, and HIV infection.26,28,30,32–34,37 The study from Nigeria also confirmed that hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, cancer, and HIV infection were predicted deaths among COVID-19 patients.41 Furthermore, the current systematic review indicates that the higher the prevalence of comorbidities like heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes, the more likely the COVID-19 patient will require intensive care or will die.42 Obesity, COPD, and CVD were also found to be risk factors for mortality among hospitalized COVID-19 patients in another systematic review.43 Thus, patients with comorbidities should take all precautions to avoid COVID-19 infection, as their prognosis is usually the worst.44

This review confirmed that non-modifiable risk factors such as sex (being male)30 and older age group30–33,37 were risk factors for COVID-19 mortality. Similarly, recent studies also reported older age groups are at a higher risk of dying from COVID-19 infection.43–45 This is because older age groups have a higher rate of occurrence of comorbid conditions than younger age groups, exacerbating fatal outcomes. Besides, the findings from Italy, Nigeria, and the current review revealed males were at higher risk of fatality.41,43,45 Aside from men’s greater contribution to comorbidities, the reasons for their higher fatality consist of behavioral, social, and biological variances that favor women.46 As a result, maintaining high-quality sex-disaggregated data is required to monitor these disparities via ensuring unbiased testing and covering population subgroups from all socioeconomic strata.47

Other important findings of this study were, behavioral risk factors like smoking34 and alcohol drinking34 were found to heighten mortality among COVID-19 patients in Ethiopia. Comparably, cigarette smoking was found to be a risk factor for mortality in a recent systematic review and study from China.43,48 This is because, smoking alters the structure of the respiratory tract and decreases the immune response, both systemically and locally within the lungs, increasing the risk of infections.49 A study from the UK showed that alcohol consumption has a negative effect on the progression of COVID-19 in white participants with obesity.50 However, a finding from China reported alcohol has no significant effect on the development of severe illness/death in general COVID-19 patients.48 In addition, another study from China reported that drinkers/smokers had a higher risk of severe COVID-19 but no higher risk of poor clinical outcomes.51 Even though alcohol drinking exaggerates organ diseases like liver and heart, increasing the risk of disease severity,50 the relationship between alcohol drinking and COVID-19 mortality should be further investigated.

As well, clinical manifestations and disease severity factors such as oxygen saturation level,28,34 lymphocyte count,33,34 worsening conditions,37 abnormal sodium level,33 shortness of breath,26,28 and fever26 were also identified to increase the likelihood of death from COVID-19 disease. These findings were aligned with studies from Nigeria,41 China,48 Peru,52 and France.53 This is due to those factors leading to the onset of clinical signs and symptoms shows the advancement of severe and critical progression to poor clinical outcomes/death.

Another important finding was, having a history of surgery/trauma32 increases the chance of mortality among confirmed COVID-19 patients in the country. This also accords with other earlier studies from Italy54 and Iran.55 This can be due to challenges in the identification and management of surgical site infection in COVID-19 patients, and hospitalization stays. Moreover, the presence of pulmonary and thrombotic complications increased the risk of mortality in COVID-19 patients who underwent surgery.54

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study include the application of explicit eligibility criteria, conduct of a comprehensive search, and novelty as there is no prior countrywide review exists. We would also like to acknowledge the main limitations of this study. First, our findings are mainly based on studies that recruited patients from health facilities and therefore, may be biased towards out-of-hospital mortality. Second, since the vast majority of the comprised studies were from medical record reviews, there could have been bias in the interpretation of the medical records and from unmeasured potential confounders. Despite these limitations, we believe that this review provides essential evidence on the current practice and future direction for COVID-19 patients in Ethiopia.

Conclusion

This study shows that the range of CFR of COVID-19 in Ethiopia is almost equivalent to other countries, despite the country’s low testing capacity and case detection rate in reference to its total population. Comorbid diseases, older age group, male sex, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, clinical manifestations and disease severity, and history of surgery/trauma were factors contributing to COVID-19 mortality in Ethiopia. Therefore, given the alarming global situation and rapidly evolving large-scale pandemics, urgent interdisciplinary interventions should be implemented in those vulnerable groups to lessen the risk of mortality. Furthermore, the CFR of COVID-19 should be estimated from all treatment and rehabilitation centers in the country, as underestimation could be linked to a lack of preparedness and mitigation. A large set of prospective studies are also compulsory to better understand the CFR of COVID-19 in Ethiopia.

Paper Context

Considerable numbers of articles on COVID-19 CFR have been published in Ethiopia. However, it is unreasonable to expect clinicians, public health experts, and the general population to read all the existing evidence on this theme. Thus, this study effectively summarizes existing evidence on COVID-19 CFR and factors contributing to mortality in Ethiopia. Consequently, implementing mitigation strategies for the synthesized factors that contribute to mortality should be emphasized urgently in order to combat the ongoing death.

Data Sharing Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

There was no specific funding received for this review.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

References

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus (COVID-19) [Internet]; 2022 [cited March 24, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1.

2. Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397

3. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) Situation Report-94; 2020:61–66.

4. World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard |WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data [Internet]; 2022 [cited March 25, 2022]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

5. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

6. Yuki K, Fujiogi M, Koutsogiannaki S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review. Clin Immunol. 2020;215:108427. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427

7. Elhiny R, Al-Jumaili AA, Yawuz MJ. An overview of post-COVID-19 complications. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(10):1–2. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14614

8. Huang D, Lian X, Song F, et al. Clinical features of severe patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(9):576. doi:10.21037/atm-20-2124

9. Ascencio-Montiel IJ, Tomás-López JC, Álvarez-Medina V, et al. A multimodal strategy to reduce the risk of hospitalization/death in ambulatory patients with COVID-19. Arch Med Res. 2022:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.07.002

10. Chavda VP, Apostolopoulos V. Mucormycosis – an opportunistic infection in the aged immunocompromised individual: a reason for concern in COVID-19. Maturitas. 2021;154:58–61. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.07.009

11. Girum T, Lentiro K, Geremew M, Migora B, Shewamare S, Shimbre MS. Optimal strategies for COVID-19 prevention from global evidence achieved through social distancing, stay at home, travel restriction and lockdown: a systematic review. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):1–18.

12. World Health Organization. Advice for the public: coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [Internet]; 2021 [cited March 25, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public.

13. Liu J, Liu S. The management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). J Med Virol. 2020;92:1–7.

14. Singhal T. A review of Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19). Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87(4):281–286. doi:10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6

15. Chavda VP, Patel AB, Vaghasiya DD. SARS‐CoV‐2 variants and vulnerability at the global level. J Med Virol. 2022;94(7):2986–3005. doi:10.1002/jmv.27717

16. Islam S, Islam T, Islam MR. New coronavirus variants are creating more challenges to global healthcare system: a brief report on the current knowledge. Clin Pathol. 2022;15:2632010X2210755. doi:10.1177/2632010X221075584

17. WHO Africa. First case of COVID-19 confirmed in Ethiopia | WHO | Regional Office for Africa [Internet]; 2020 [cited April 28, 2021]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/first-case-covid-19-confirmed-ethiopia.

18. World Health Organization. Ethiopia: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) dashboard with vaccination data [Internet]; 2022 [cited March 25, 2022]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/et.

19. Worldometer. COVID Live - Coronavirus Statistics - Worldometer [Internet]; 2022 [cited March 25, 2022]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries.

20. Our World in Data. Ethiopia: coronavirus pandemic country profile-Our World in Data [Internet]; 2021 [cited April 29, 2021]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/ethiopia.

21. Mohammed H, Oljira L, Roba KT, Yimer G, Fekadu A, Manyazewal T. Containment of COVID-19 in Ethiopia and implications for tuberculosis care and research. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s40249-020-00753-9

22. Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-Fatality Rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323(18):1775–1776.

23. Akbari M, Fayazi N, Kazemzadeh Y, et al. Evaluate the Case Fatality Rate (CFR) and Basic Reproductive Rate (R-naught) of COVID-19. Curr Health Sci J. 2021;47(2):274.

24. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi:10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

25. Gebremariam BM, Shienka KL, Kebede BA, Abiche MG. Epidemiological characteristics and treatment outcomes of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37(Suppl 1):7. doi:10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.37.1.24436

26. Leulseged TW, Maru EH, Hassen IS, et al. Predictors of death in severe COVID-19 patients at millennium COVID-19 care center in Ethiopia: a case-control study. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38:351. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.351.28831

27. Abdela SG, Abegaz SH, Demsiss W, Tamirat KS, van Henten S, van Griensven J. Clinical profile and treatment of covid-19 patients: experiences from an Ethiopian treatment center. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104(2):532–536. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-1356

28. Leulseged TW, Hassen IS, Maru EH, et al. Characteristics and outcome profile of hospitalized African patients with COVID-19: the Ethiopian context. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0259454. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0259454

29. Tolossa T, Wakuma B, Seyoum Gebre D, et al. Time to recovery from COVID-19 and its predictors among patients admitted to treatment center of Wollega University Referral Hospital (WURH), Western Ethiopia: survival analysis of retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252389. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0252389

30. Kebede F, Kebede T, Gizaw T. Predictors for adult COVID-19 hospitalized inpatient mortality rate in North West Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2022;10:205031212210817. doi:10.1177/20503121221081756

31. Geteneh A, Alemnew B, Tadesse S, Girma A. Clinical characteristics of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in North Wollo Zone, North-East Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38:217. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.217.27859

32. Abraha HE, Gessesse Z, Gebrecherkos T, et al. Clinical features and risk factors associated with morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19 in northern Ethiopia. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;105:776–783. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.037

33. Leulseged TW, Hassen IS, Ayele BT, et al. Laboratory biomarkers of COVID-19 disease severity and outcome: findings from a developing country. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246087. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246087

34. Ayana GM, Merga BT, Birhanu A, Alemu A, Negash B, Dessie Y. Predictors of mortality among hospitalized COVID-19 Patients at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:5363–5373. doi:10.2147/IDR.S337699

35. Teklu S, Sultan M, Azazh A, et al. Clinical and socio-demographic profile of the first 33 COVID-19 cases treated at dedicated treatment center in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2020;30(5):645–652. doi:10.4314/ejhs.v30i5.2

36. Gudina EK, Gobena D, Debela T, et al. COVID-19 in Oromia Region of Ethiopia: a review of the first 6 months’ surveillance data. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e046764. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046764

37. Kaso AW, Hareru HE, Kaso T, Agero G. Factors associated with poor treatment outcome among hospitalized COVID-19 patients in South Central, Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:4551132. doi:10.1155/2022/4551132

38. Alimohamadi Y, Tola HH, Abbasi-Ghahramanloo A, Janani M, Sepandi M. Case fatality rate of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prev Med Hyg. 2021;62(2):E311–20. doi:10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2021.62.2.1627

39. Undela K, Gudi SK. Assumptions for disparities in case-fatality rates of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) across the globe. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(9):5180–5182. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202005_21215

40. Sorci G, Faivre B, Morand S. Explaining among-country variation in COVID-19 case fatality rate. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–11. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-75848-2

41. Osibogun A, Balogun M, Abayomi A, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 patients with comorbidities in southwest Nigeria. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248281

42. Espinosa OA, Zanetti ADS, Antunes EF, Longhi FG, Matos TA, Battaglini PF. Prevalence of comorbidities in patients and mortality cases affected by SARS-CoV2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2020;62:119–123. doi:10.1590/s1678-9946202062043

43. Dessie ZG, Zewotir T. Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1). doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06536-3

44. Guan WJ, Liang WH, He JX, Zhong NS. Cardiovascular comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(6):1069–1076. doi:10.1183/13993003.01227-2020

45. Fortunato F, Martinelli D, Lo Caputo S, et al. Sex and gender differences in COVID-19: an Italian local register-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):1–7. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051506

46. Sharma G, Volgman AS, Michos ED. Sex differences in mortality from COVID-19 pandemic. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2(9):1407–1410. doi:10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.027

47. Dehingia N, Raj A. Sex differences in COVID-19 case fatality: do we know enough? Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(1):e14–5. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30464-2

48. Dai M, Tao L, Chen Z, et al. Influence of cigarettes and alcohol on the severity and death of COVID-19: a multicenter retrospective study in Wuhan, China. Front Physiol. 2020;11:

49. Arcavi L, Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and infection. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2206–2216. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.20.2206

50. Fan X, Liu Z, Poulsen KL, et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with poor prognosis in obese patients with covid‐19: a Mendelian randomization study using UK biobank. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1–22. doi:10.3390/nu13051592

51. Fang XM, Wang J, Liu Y, et al. Combined and interactive effects of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking on the risk of severe illness and poor clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Public Health. 2022;205:6–13. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2022.01.013

52. Mejía F, Medina C, Cornejo E, et al. Oxygen saturation as a predictor of mortality in hospitalized adult patients with COVID-19 in a public hospital in Lima, Peru. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244171

53. Assaad S, ZroSunba P, Cropet C, Blay JY. Mortality of patients with solid and haematological cancers presenting with symptoms of COVID-19 with vs without detectable SARS-COV-2: a French nationwide prospective cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2021;125(5):658–671. doi:10.1038/s41416-021-01452-4

54. Doglietto F, Vezzoli M, Gheza F, et al. Factors associated with surgical mortality and complications among patients with and without Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(8):691–702. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2713

55. Mohammadpour M, Yazdi H, Bagherifard A, et al. Evaluation of early complications, outcome, and mortality in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in patients who underwent orthopedic surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12891-022-05010-8

56. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.