Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 13

Comorbidity of schizophrenia and social phobia – impact on quality of life, hope, and personality traits: a cross sectional study

Authors Vrbova K, Prasko J , Ociskova M , Holubova M

Received 15 May 2017

Accepted for publication 26 June 2017

Published 3 August 2017 Volume 2017:13 Pages 2073—2083

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S141749

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Kristyna Vrbova,1 Jan Prasko,1 Marie Ociskova,1 Michaela Holubova1,2

1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacky University Olomouc, University Hospital Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic; 2Department of Psychiatry, Hospital Liberec, Liberec, Czech Republic

Objective: The purpose of the study was to explore whether the comorbidity of social phobia affects symptoms severity, positive and negative symptoms, self-stigma, hope, and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study in which all participants completed the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale, Adult Dispositional Hope Scale (ADHS), Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q), Temperament and Character Inventory – Revised (TCI-R), and the demographic questionnaire. The disorder severity was assessed both by a psychiatrist (Clinical Global Impression Severity – the objective version [objCGI-S] scale) and by the patients (Clinical Global Impression Severity – the subjective version [subjCGI-S] scale). The patients were in a stabilized state that did not require changes in the treatment. Diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder was determined according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) research criteria. A structured interview by Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview was used to confirm the diagnosis.

Results: The study included 61 patients of both genders. Clinically, the patients with comorbid social phobia had the earlier onset of the illness, more severe current psychopathology, more intense anxiety (general and social), and higher severity of depressive symptoms. The patients with comorbid social phobia showed the significantly lower quality of life compared to the patients without this comorbidity. The patients with comorbid social phobia also had a statistically lower mean level of hope and experienced a higher rate of the self-stigma. They also exhibited higher average scores of personality trait harm avoidance (HA) and a lower score of personality trait self-directedness (SD).

Conclusion: The study demonstrated differences in demographic factors, the severity of the disorder, self-stigma, hope, HA, and SD between patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders with and without comorbid social phobia.

Keywords: schizophrenia, social phobia, onset, hospitalizations, quality of life, self-stigma, hope, personality traits

Introduction

The current process of diagnosing psychoses often predominantly focuses on the exploration of the psychotic symptoms while overlooking the symptoms of possible comorbidities, such as the anxiety disorders. Recent studies have shown that the anxiety symptoms and the anxiety disorders can be a significant source of morbidity in the patients with psychoses.1–3 Out of the correctly recognized comorbid anxiety disorders, the most frequent one in the patients with schizophrenia is a social phobia. The incidence of the comorbid social phobia in psychotic disorders lies in the range from 11 to 36%.4–8 It is a frequently unrecognized problem that is associated with more severe psychotic symptoms, poorer quality of life, and lower self-esteem.9,10 It is an additional burden that further deteriorates the life functioning and overall worsens social adaptation.7,11 The causes of a higher incidence of the social phobia in the patients with schizophrenia have not been sufficiently explored yet. However, the changes in the social involvement of the patients are present before the clinical onset of schizophrenic disease.9 The potential reason for the increased rate of social phobia in patients with schizophrenia is that social anxiety is a basic factor of disorder of schizophrenia per se. Thus, as the disorder progresses, social anxiety increases in link with the occurrence of signs. Nevertheless, there is little data for this interpretation: Pallanti et al11 showed that social phobia was not related to the positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Another option is that social phobia exists in premorbidity and it is a factor which increased vulnerability for the development of schizophrenia.10 A third option is that social phobia occurred as a psychosocial response to schizophrenia.12–14 Pallanti et al11 found that social phobia emerged in the course of the recovery period. An essential condition for this interpretation would be confirmation that people who developed schizophrenia are stigmatized and highly internalized the stigma.14,15

If social phobic symptoms remain unrecognized and untreated, they are associated with more severe symptoms of psychosis and lower self-esteem. At the same time, lower premorbid self-esteem is a risk factor for the development of the social phobia.12 Romm et al2 also reported that severe social anxiety in the patients with the first psychotic episode is associated with a worse premorbid function. Mazeh et al7 found that patients with the comorbid social phobia had significantly higher scores in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and also in the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) compared to the patients without the social phobia comorbidity. Social phobia also has been associated with negative symptomatology because of the typical avoidance behavior.7,13 However, in the study of Pallanti et al,11 there were no differences in the severity of the negative and positive symptoms in the schizophrenic patients with or without the social phobia.

According to Birchwood et al,14 who elaborated on the social status theory, the comorbid social phobia can be developed in the expectation of a devastating loss of the social status. The patients expect these feelings in relation with the social stigmatization connected with schizophrenia and also experience greater shame associated with that diagnosis and lowered social status due to psychosis. Thus, the authors of the study concluded that the self-stigma could largely contribute to the development of the social phobia in the schizophrenic patients.

Lysaker et al15 investigated the relationship of self-esteem, self-confidence, positive and negative symptoms, and emotional discomfort in the context of the social phobia development. There were a total of 78 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who participated in the study. The results showed that low self-esteem, high self-stigma, negative symptoms, and emotional difficulties were significantly related to the degree of social anxiety assessed both at the beginning of the study and after 5 months of follow-up. According to a multiple regression analysis, the negative symptoms and experiences of discrimination may predict the development of social anxiety, even when the initial severity of social anxiety is low.

Awareness of disorder and insight increase functional outcome.12 However, if insight is going together with the self-stigma, it weakens social and occupational functioning and lessens the hope.15

According to Snyder’s theory, hope is related to the life goals and expectations of a positive outcome of the own effort.33,34 His concept of hope includes emotion, motivation, behavior, and cognition.34 The basic level of hope remains relatively stable over time, which makes it resemble a personality trait.33 In schizophrenia patients, the relationships among self-stigma, hope, and depression are interconnected.35

From typical personality traits of patients with the schizophrenic disease, they differ from the healthy population in several characteristics. The schizophrenia patients repeatedly displayed a higher score of harm avoidance (HA) and a lower score of reward dependence (RD) in comparison with healthy persons.36,37 The results of novelty seeking (NS) and persistence (PS) are unambiguous. Some studies have established a lower score in NS and PS,36,37 but the most studies have not found statistically significant differences in comparison with the healthy controls.38–41 In the character traits such as cooperativeness (CO) and self-directedness (SD), patients with schizophrenia had lower scores, and in self-transcendence (ST), patients with schizophrenia had higher scores compared to controls in some studies.37,42,43

As shown earlier, many factors were investigated before, but little is known about the interactions of these factors. There were also some factors that are not investigated systematically before the present study, such as the interaction of hope and self-stigma and difference between hope in patients with and without comorbid social phobia.

The main objective of the study was to determine whether the comorbid social phobia affects the severity of symptoms, the self-stigma, the positive and negative symptoms, hope, and the quality of life in the patients with the schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Another objective was to explore whether this comorbidity is related to the personality characteristics of the patient. The main hypotheses were that the patients with the comorbid social phobia have 1) an earlier age of the onset of illness, a longer duration of the illness, and more hospitalizations; 2) greater severity of the symptoms and worse general severity of the disorder; 3) a lower level of hope; 4) a higher rate of the self-stigma; and 5) a higher level of the personality trait HA and a lower level of the personality trait SD, in comparison with the patients without the comorbid social phobia.

Methods

The data were collected in the period from September 2016 to March 2017. The questionnaires were offered to 70 patients with schizophrenic illness who were attending the outpatient facility at the Psychiatric Clinic in Olomouc, Czech Republic. The participation in the research and filling in the questionnaires was voluntary.

Sample

The study included 61 patients of both genders, who visited the outpatient facility. The patients were in a stabilized state that did not require a hospitalization or changes in the treatment. The diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder was determined according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) research criteria.16 The mix of patients with schizophrenia and delusional disorder is not ideal. Nevertheless, the category of the delusional disorder is a part of a bigger group of schizophrenia-related disorder, the treatment is similar, and outcome in most patients is also similar. A structured interview by Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) was used to confirm the diagnosis.17 The criteria for the inclusion in the study were as follows:

- age 18–65 years, and

- diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder according to the ICD-10 research criteria.16

The exclusion criteria were a severe physical illness, mental retardation, or an organic psychotic disorder.

Assessment instruments

After the therapist briefly discussed the sense of the study and provided the information of the study, the patients completed the panel of questionnaires. The severity of disorder was determined by a thorough interview with the psychiatrist who evaluated the severity on the Clinical Global Impression Severity – the objective version (objCGI-S) scale. The following assessment and evaluation tools were used in the study:

- PANSS18 – The scale consists of 30 items divided into three subcategories: seven positive (PANSS P), seven negative (PANSS N), and 16 general psychopathological symptoms. Each item is rated from 1 (absent) to 7 (extremely present). The total score is the sum of all points, called PANSS total (PANSS T). Remission is usually defined as a score of <3 in all positive PANSS items.

- Clinical Global Impression (CGI)19 – The CGI is the assessment of the overall severity of the disorder. The objCGI-S is a global evaluation of the patient’s mental state by a physician. The objCGI reflects the seriousness of all symptomatology together (psychotic symptoms, anxiety, and depressive) in one number. In Clinical Global Impression Severity – the subjective version (subjCGI-S), the patient himself evaluates his overall condition. The range of the scale is from 1 (normal, with no signs of illness) to 7 (extremely severe symptoms of the disease).

- Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)20 – The BDI contains 21 items in which the patient selects one of the four defined options that best corresponds to how he feels over the past 2 weeks. The correlation of BDI-II with other standardized depression scales is ~0.70, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) ranges from 0.73 to 0.95.21 The scale is widely used to assess the current level of depressive symptomatology in the clinic and research. The test was adapted to the Czech population.22

- Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)23 – The Beck Anxiety Scale is made up of 21 items with a 4-point Likert scale, according to which the individual indicates the severity of the anxiety symptoms they suffered in the last week. BAI was validated in Czech by Kamaradova et al.24 The inventory shows excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.92).24

- LSAS25 – The questionnaire comprised 24 items that capture different social situations. In each situation, the clinician asks the patient for the level of fear and the avoidance of the 4-point Likert scale. The fear scale ranges from 0 (no fear) to 3 (severe fear). The avoidance scale has the same range and is based on the percentage of cases when a patient avoids a given situation (0= never; 1= occasionally [10%]; 2= often [33%–67%]; 3= always). In addition to the fears and avoidance scale, LSAS is further subdivided into two subscales that evaluate social interactions (11 items) and performance situations (13 items). The scale has an objective and subjective (self-rate) version, with a shift in evaluation – instead of 0–3, 1–4 is used. LSAS (LSAS-SR) has excellent psychometric properties, as shown by its test–retest, internal consistency, and the sensitivity to therapeutic change.26

- Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q)27 – The questionnaire is measuring the quality of life (experiencing joy and satisfaction in life). This questionnaire has been used to assess the quality of life in patients with panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, and alcohol addiction. The Q-LES-Q consists of eight sections focusing on physical health (13 questions), feelings (14 questions), work activities (13 questions), home care (10 questions), study activities (10 questions), leisure time (six questions), social relationships (11 questions), and a general view on the quality of life (16 questions). Satisfaction with the eight areas is expressed by the patient on a 5-point assessment scale. Test–retest reliability was performed in 54 patients, with correlations between the measurements ranging from 0.63 to 0.89, and the internal consistency was 0.90.28 Validation in the Czech language was performed in a sample of individuals suffering from a depressive disorder.29

- Temperament and Character Inventory – Revised (TCI-R)30 – The TCI-R consists of 240 items. The questionnaire evaluates four temperamental and three character personality traits. Features of temperament include NS, HA, RD, and PS. Characteristic features include SD, CO, and ST.31 Preiss and Klose32 created Czech percentile standards.

- Adult Dispositional Hope Scale (ADHS)33 – The scale has the following 12 items: four items assess the ability to define adaptive paths to reach a goal, four items focus on an inner motivation to strive for them, and four items serve as distractors. The patient chooses the degree of agreement with each statement on an 8-point scale. The Czech translation and standardization were created by Ocisková et al.34 The translation showed a good degree of internal consistency – the total Cronbach’s α was 0.85.34

- The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale44 – The scale consists of 29 items with a 4-point Likert scale and evaluates the following five areas of the self-stigma: alienation, stereotypes endorsement, perceived discrimination, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance.44,45 The Czech version of the ISMI was standardized by Ocisková et al.46 Internal consistency of the Czech text of the scale was excellent (the Cronbach’s α=0.91).

- Demographic questionnaire contained the basic information – gender, age, marital status, education, employment, disability, age of the disorder onset, duration of attendance to the psychiatric services, number of hospitalizations, time since last hospitalization, number of visited psychiatrists, medication, and medication discontinuation in the past (on the recommendation of a psychiatrist or willingly).

Statistics and ethics

The statistical programs Prism (GraphPad PRISM Version 5.0; http://www.graphpad.com/prism/prism.htm) and SPSS 24.0 were used for the statistical evaluation of the results. Demographic data, the average scores, and standard deviations in the scales were calculated using the descriptive indicators. Means were compared by using independent t-tests. Relations between categories have been assessed by using correlation coefficients. Fisher’s exact test verified the relationship between dichotomous variables (gender, marital status, and drop out of the medication). The backward stepwise regression tested the significance of each correlation between others. All statistical tests were considered significant at the 5% level of statistical significance.

The study was approved by the local hospital ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Palacky University Olomouc. The research was conducted by the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and recommendations for good clinical praxis (EMEA 2002).48 All probands signed their approval for the participation in the research. They were informed of the voluntary participation and the possibility to withdraw without giving any reason and to oppose the use of the data. They were acquainted both in writing and verbally about the nature of the research, its course, the demands that it would have made, and the benefits that it would bring to researchers as well. All participants signed written informed consent for this study.

Medication management

All patients included in the trial were using antipsychotics at therapeutic doses (5.8±3.9 mg antipsychotic dose, calculated on the risperidone index). In addition to the antipsychotic medication, 27 (44.3%) patients were treated with antidepressants (29.1±13.3 mg antidepressants per paroxetine dose), eight (13.1%) patients with benzodiazepine anxiolytics (mean dose 9.4±4.2 mg per dose of diazepam), and eight (13.1%) patients with mood stabilizers (4× valproate, 2× lithium carbonic, and 2× lamotrigine). The drugs were managed according to the recommended guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia (Češková et al, 201447). A total of 61 patients reported that they used recommended medication prescribed by the attending psychiatrist.

Results

Description of the sample

Questionnaires were completed by 61 (81.7%) patients meeting the entry criteria. The mean age was 35.6 years, and the duration of illness was 7.3 years (Table 1). There were slightly more women than men (51.7%). The education received was relatively regularly distributed: 13% of the patients had basic education, 33.3% had vocational training, 27.5% had secondary education, and 14.5% reached the university level of education. Fifty percent of the patients were unemployed, 50% were employed or self-employed, and in one patient, the data were missing. A total of 36.7% of the patients had a full disability pension; another 16.7% were taking a partial one. About their family status, 58.3% of the patients were single, another 18.3% were married, and 10.0% were divorced. A third of the patients (31.7%) had a partner (Table 1).

A primary diagnosis was from the schizophrenic spectrum disorder in all 61 patients (52.5% schizophrenia, 4.9% delusional disorder, 23.0% acute and transient psychotic disorder, and 7% schizoaffective disorder). In 80.3% of the patients, a comorbid disorder was also diagnosed: 31.1% had social phobia, 14.8% had panic disorder/agoraphobia, 3.3% had obsessive compulsive disorder, 23.0% had affective disorder (depression 19.7% and dysthymia 3.3%), and 18.5% were found to deal with a substance abuse (11.5% alcohol, 11.5% marijuana, and 6.6% both). Forty-one percent of the patients discontinued medication in the past without a physician’s recommendation.

Regarding the severity of the disorder, the current severity of the disorders ranged between “mildly ill” and “moderately ill” according to the objCGI-S. The subjective assessment of the disease severity (subjCGI-S) by the patients was significantly lower compared to the objective evaluation (objCGI-S) (Mann–Whitney [MW] test, U=1,331; P<0.01). Still, the subjective and objective assessments of the severity of the disorder highly significantly correlated to each other (Spearman’s r=0.57, P<0.0001).

Comorbidity with social phobia

The comorbid social phobia was diagnosed in 19 patients (31.1%). The patients with the comorbid social phobia, defined by the structured MINI, were statistically significantly different from those without comorbid social phobia in a range of the demographic data, such as the earlier onset of the illness development, higher hospitalization rates, and longer duration of the disease (Table 2).

The mean doses of the antipsychotics and antidepressants did not significantly differ between the groups, but significantly more patients with the comorbid social phobia were using antidepressants compared to the patients without the social phobia (Fisher’s exact test: P<0.005).

Among the patients with the comorbid social phobia and the patients without such comorbidity, the statistically significant difference is also in the mean overall score of PANSS, objCGI-S, subjCGI-S, BDI-II, BAI, LSAS, and Q-LES-Q (Table 2 and Figure 1).

The comorbid patients also had a statistically lower mean level of hope (ADHS) and experienced a more pronounced self-stigma (ISMI) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

The TCI-R personality inventory showed that the patients with the comorbid social phobia exhibited a significantly higher HA and lowered SD (Table 2 and Figure 3).

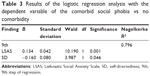

Logistic regression – the presence or the absence of the comorbid social phobia

After the identification of some correlates of the social phobia comorbidity, a logistic regression analysis was useful to identify the most significant factors connected to it. The presence or the absence of a comorbid social phobia was a dependent element in the analysis. The independent variables were the age of onset of the disorder, the number of hospitalizations, the length of the illness, objCGI-S, subjCGI-S, LSAS, PANSS, BDI-II, BAI, HA, and SD. These all were variables in which the group of the patients with the comorbid social phobia previously significantly differed from the group without this comorbidity.

The results of the regression analysis are shown in Table 3. The numerical data are always positive, so it cannot be deduced from the direction of the relationship, but it shows the nonstandardized values of B.49 The Nagelkerke R2 is then similar to the R2, which is known from linear regressions. It tells about the extent to which the model explains the variance of the scaled variables. With the increasing size of the indicators, the predictive value of the model increases.49,50 The strongest factor connected to the presence of the comorbid social phobia according to this model was the severity of the social anxiety assessed by LSAS and the personality trait of SD. These two factors explained the occurrence of the comorbid social phobia of 79.6% (Table 3). Other factors have been excluded as less significant from the model in the individual steps of the logistic regression.

Discussion

According to some studies, a comorbid social phobia is the most common comorbid anxiety disorder in the patients with schizophrenia.5,6 In the present study, the MINI found the comorbid social phobia in 31.3% of the patients and that it was the most common comorbid disorder. This is consistent with the results of other studies where this comorbidity was found to be between 11 and 36%.1,4,8,11,51,52

The “first hypothesis” was that the patients with the comorbid social phobia have an earlier onset of the disorder, a longer duration of the disorder, and a higher number of hospitalizations compared to the patients without the comorbid social phobia. The presented study confirmed the hypothesis. The onset of the illness occurred in the comorbid patients 8 years earlier on average. These patients also had had significantly more hospitalizations, and their illness lasted longer. The finding that there is an earlier onset of the disorder in the patients with the social phobia is unique. It was not described in other studies as they did not focus on the illness at its beginning. A significantly higher number of hospitalizations in this comorbidity were also not described before the presented study.

The “second hypothesis” was that the patients with the comorbid social phobia have a higher symptoms severity compared to the patients without the comorbid social phobia. This hypothesis was also confirmed. The objectively and subjectively assessed severity of the illness was higher in the individuals with this comorbidity; the severity of the schizophrenic symptomatology, depressive symptoms, general anxiety, and social anxiety were also greater. Similar results appeared in some other studies. Güçlü et al51 examined the relationship between the social phobia and the clinical symptoms of the schizophrenic disorder. Their scores of depressive symptoms were higher than those in our study. Mazeh et al7 found that the patients with the comorbid social phobia achieved significantly higher scores on the PANSS compared to the individuals without the comorbidity. In the study of Pallanti et al,11 the comorbid patients showed a higher average score on the LSAS.

The patients with comorbid social phobia had significantly higher scores of LSAS compared to patients without social phobia. Additionally, the results of the logistic regression analysis with the dependent variable of the comorbid social phobia vs no comorbidity show that LSAS score was the most important factor explaining the presence of social phobia.

The “third hypothesis” was that the patients with the comorbid social phobia have lower hope compared to the patients without comorbid social phobia. As demonstrated by the results of this study, this hypothesis was confirmed. The assessment of hope shows a mean lower value in the comorbid patients than in the patients without comorbidity. The relationship between hope and the comorbidity in the patients with a schizophrenic illness has not been studied yet, so it is a unique finding. However, in the study by Pallanti et al,11 the schizophrenic patients with the comorbid social phobia were found to have a lifetime of suicidal attempts in a more lethal way, which may be associated with higher levels of hopelessness in this comorbid group.

According to Snyder’s theory of hope, on which the ADHS is based, the experience of hope appears when the individual has a goal that he/she wants to achieve, identified paths to reach the target, and a sufficient degree of motivation to be on the road.33 It is possible that the presence of the social phobia can interfere with self-confidence so much that the patient does not believe that he/she can achieve his/her goal and, thus, loses his/her motivation to achieve the goals, especially if they are interpersonal in nature. As with other hypotheses, a cross-sectional study cannot find out whether a comorbid social phobia has previously developed or whether there has been a loss of hope first, but it is possible that both problems interact with each other. The earlier age of illness development may have prevented the development of social and problem-solving skills, which diminished self-confidence and led to the avoidance of the social situations.

The “fourth hypothesis” was that the patients with the comorbid social phobia have a higher rate of the self-stigma compared to the patients without the comorbid social phobia. The hypothesis was confirmed by the results of the study. The degree of self-stigma is significantly higher in patients with a comorbid social phobia. Whether a higher degree of self-stigma preceded the development of social anxiety or vice versa, the result of the correlation study cannot be ascertained. However, the findings of the presented study are consistent with the results of studies by other authors.8,53 Similarly, Birchwood et al14 attempted to explain this relationship. These authors views on the theory of social status when they assumed that one of the ways through which social phobia can develop in patients with schizophrenia is the expectation of a devastating loss of social status. Patients expect this as a result of the social stigma of mental disorders. Patients with social anxiety in their study experienced greater feelings of shame associated with the diagnosis of psychosis; they were convinced that they had a low social status due to psychosis. The authors of the study concluded that the self-stigma could largely contribute to the development of social phobia in schizophrenic patients. In further studies dealing with this subject, Lysaker et al15 investigated the relationship of self-stigma, self-esteem, positive and negative symptoms, and emotional discomfort in the context of social phobia development. The results showed that low self-esteem, self-stigma, negative symptoms, and emotional difficulties were significantly related to the level of social anxiety assessed both at the beginning of the study and after 5 months of follow-up. Using multiple regression, it has been set up that the negative symptoms and the experiences of discrimination predict the development of social anxiety prospectively, even though the initial rate of social anxiety was low.

The “fifth hypothesis” was that the patients with the comorbid social phobia have higher scores of personality trait HA and lower of the personality trait SD compared to patients without the comorbid social phobia. The hypothesis was confirmed. There is a statistically significant difference in HA, which is higher in the patients with the comorbidity, and also a significant difference in SD, which is significantly lower in this group. HA measures the tendency to respond with overall attenuation to aversive stimuli.54 The HA is associated with an increased vulnerability to criticism and rejection and the resulting tendency to avoidant behavior.55 This trait predicts both social isolation and gradually increasing negative feelings in contact with people and a poor quality of life in individuals with the schizophrenic disorder. Despite the fact that Cloninger et al ranks HA to temperament traits, a predominantly inherent characteristic of the schizophrenia, it is not yet clear whether during the psychotic process this feature can be amplified.56 The question of the causality of these relationships cannot be answered from the findings of this study because it was a cross-sectional evaluation. It is unclear whether patients who have a social phobia have developed it earlier, or whether patients who have developed schizophrenic disorder before later develop social phobia.57,58

SD is one of the character traits of personality, ie, functions that are widely influenced by the life experiences.58 Cloninger believes that SD can change over the course of life.59 It is also very likely that the psychotic illness, but also a high degree of personal anxiety in social situations, leads to a decline in SD. In the logistic regression assessing which variables saturate the presence of the social phobia the most, it turned out that SD as the only personality trait was not eliminated in the individual steps of the regression and remained present until the last step. This means that the individuals, who know what they want in life, are responsible, accept themselves, and suffer from the social phobia less often.

These results indicate that psychosocial interventions such as psychoeducation of psychotic patients, and their family, and also specific oriented psychotherapy of psychoses, which also includes working with social anxiety symptomatology with the work on reducing of the self-stigma, strengthening the PS by increasing the self-esteem, training of the communication skills, and problem solving, could help to increase quality of life of our patients. Next prospective studies investigating above approaches are needed in the future.

Limitations of the study

Several factors are limiting the possibilities of generalizing the results of this study. The research was conducted only at one workplace, so the population of the schizophrenic patients may not have been representative, in particular on the willingness to cooperate. However, the previous study,60 which was carried out in many outpatient clinics at the same time, has similar demographic characteristics of the patients, so there was probably no significant shift due to the features of the workplace.

Another significant limitation of the study is the fact that it was a cross-sectional study that cannot explain the causality described by the correlations, which are also multiples between factors, and therefore unclear for the collinearity between the factors. An attempt to reduce this constraint was the use of regression step analysis that excluded collinear factors from each other and allowed only the most significant factors to pass. However, it is necessary to recognize the limitations of these statistical tools with a relatively small number of probands. The step regressions were performed with the knowledge that the number of probands was not optimal and were used in particular to illustrate the results. Most of the results, however, are consistent with the findings of other authors who have explored a similar topic. Some findings, however, are unique, and comparison with the results of other authors was not possible.

Other limitations can be the inclusion of a delusional disorder in the sample, which put into question the validity of the comparison. The mix of schizophrenia and delusional disorder is not ideal. Nevertheless, there were only three patients with the delusional disorder, and delusional disorder is a part of a bigger group of the schizophrenia-related disorders. According to our experiences, the treatment of this disorder is similar. However, it is possible that this limitation can decrease the generalization of the results.

Other limitations of the study may be a range of the self-assessment questionnaires. The fact that part of the data was collected by the patient-filled questionnaires in which we are reliant on the patient’s introspection ability and his willingness to testify has limitations, particularly in the patients with schizophrenia who may suffer from varying degrees of a cognitive dysfunction. In addition to the demographic data, the objective CGI, and the medication doses, the patient-filled questionnaires could be modified by various levels of tiredness and patients’ motivation. However, as objective assessment scales such as PANSS have been used, the objective evaluation of the severity of symptoms that significantly correlates with the subjective assessment scales, the use of subjective rating scales, and questionnaires may not be what the results of the study necessarily disqualify. Also, the diagnosis of schizophrenic illness, including comorbidities, was determined according to a structured interview by MINI.

Another limitation of the study is that the patients in the study used different medications. We have tried to reduce the impact of this variable by converting the dosages of the drugs to the standardized index scores, but we cannot rule out the possible effect of the different medications on the severity of the assessed symptoms.

This study can be seen as a pilot study that outlines the possibility of further investigating the impact of various social, psychological, and psychopathological influences on the quality of life of the people with the psychotic disorder.

Conclusion

In the patients with the comorbid social phobia compared to the patients without the comorbid social phobia, the illness occurs at the earlier age, the patients have more psychotic episodes and more psychiatric hospitalizations, their current psychopathology is more severe, and the overall severity of the disorder is higher. Also, they suffer from higher anxiety, both general and social, with a higher severity of depressive symptoms and have a more manifest personality trait of HA and decreased trait of SD. The average rate of the self-stigma is also higher, hope is decreased, and the quality of life is lower than in patients without social phobia.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Voges M, Addington J. The association between social anxiety and social functioning in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(2–3):287–229. | ||

Romm KL, Melle I, Thoresen C, Andreassen OA, Rossberg JA. Severe social anxiety in early psychosis is associated with poor premorbid functioning, depression, and reduced quality of life. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(5):434–440. | ||

Young S, Pfaff D, Lewandowski KE, Ravichandran C, Cohen BM, Öngür D. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Psychopathology. 2013;46(3):176–185. | ||

Cosoff SJ, Hafner RJ. The prevalence of comorbid anxiety in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32(1):67–72. | ||

Ciapparelli A, Paggini R, Marazziti D, et al. Comorbidity with axis I anxiety disorders in remitted psychotic patients 1 year after hospitalization. CNS Spectr. 2007;12(12):913–919. | ||

Michail M, Birchwood M. Social anxiety disorder in first-episode psychosis: incidence, phenomenology, and relationship with paranoia. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):234–241. | ||

Mazeh D, Bodner E, Weizman R, et al. Co-morbid social phobia in schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2009;55(3):198–202. | ||

Achim AM, Maziade M, Raymond E, Olivier D, Mérette C, Roy MA. How prevalent are anxiety disorders in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis and critical review on a significant association. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(4):811–821. | ||

Braga RJ, Mendlowicz MV, Marrocos RP, Figueira IL. Anxiety disorders in outpatients with schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on the subjective quality of life. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39(4):409–414. | ||

Achim AM, Ouellet R, Lavoie MA, Vallières C, Jackson PL, Roy MA. Impact of social anxiety on social cognition and functioning in patients with recent-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Schizophr Res. 2013;145(1–3):75–81. | ||

Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Hollander E. Social anxiety in outpatients with schizophrenia: a relevant cause of disability. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(1):53–58. | ||

Lysaker PH, Tsai J, Yanos P, Roe D. Associations of multiple domains of self-esteem with four dimensions of stigma in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;98(1–3):194–200. | ||

Penn DL, Hope DA, Spaulding W, Kucera J. Social anxiety in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1994;11(3):277–284. | ||

Birchwood M, Trower P, Brunet K, Gilbert P, Iqbal Z, Jackson C. Social anxiety and the shame of psychosis: a study in first episode psychosis. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(5):1025–1037. | ||

Lysaker PH, Yanos PT, Outcalt J, Roe D. Association of stigma, self-esteem, and symptoms with concurrent and prospective assessment of social anxiety in schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2010;4(1):41–48. | ||

Mezinárodní klasifikace nemocí – 10. revize, MKN-10 (1. vydání). International Classification of Diseases – 10th revision. Praha: Maxdorf; 1996. Czech. | ||

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33. | ||

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. | ||

Guy W, editor. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: U.S. DHEW; 1976. | ||

Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-I and −II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67(3):588–597. | ||

Domino G, Domino ML. Psychological Testing: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press; 2006. | ||

Preiss M, Vacíř K. Beckova sebeposuzovací škála depresivity pro dospělé. [Beck self-assessment scale for depression]. BDI-II. Příručka. Brno: Psychodiagnostika; 1999. Czech. | ||

Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–897. | ||

Kamaradova D, Prasko J, Latalova K, et al. Psychometric properties of the Czech version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory – comparison between diagnostic groups. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2015;36(7):706–712. | ||

Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. | ||

Baker SL, Heinrichs N, Kim HJ, Hofmann SG. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale as a self-report instrument: a preliminary psychometric analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(6):701–715. | ||

Ritsner M, Ben-Avi I, Ponizovsky A, Timinsky I, Bistrov E, Modai I. Quality of life and coping with schizophrenia symptoms. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(1):1–9. | ||

Katschnig H. How useful is the concept of quality of life in psychiatry? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 1997;10:337–345. | ||

Müllerova H, Libigerova E, Prouzova M, et al. Mezikulturní přenos a validace dotazníku kvality života Q-LES-Q (Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire) v populaci nemocných s depresivní poruchou [Cross-cultural transfer and validation of the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire in the population of depressed patients]. Psychiatrie. 2001;5:80–87. Czech. | ||

Farmer RF, Goldberg LR. A psychometric evaluation of the revised Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-R) and the TCI-140. Psychol Assess. 2008;20(3):281. | ||

Gillespie NA, Cloninger CR, Heath AC, Martin NG. The genetic and environmental relationship between Cloninger’s dimensions of temperament and character. Pers Individ Dif. 2003;35(8):1931–1946. | ||

Preiss M, Klose J. Diagnostika poruch osobnosti pomocí teorie. [Diagnostic of personality disorders using teory of CR Cloninger]. C R Cloningera Psychiatrie. 2001;5:226–231. Czech. | ||

Snyder CR, editor. Handbook of Hope: Theory, Measures, & Applications. New York, NY: Academic Press; 2000. | ||

Ocisková M, Sobotková I, Praško J, Mihál V. Standardizace české verze Snyderovy škály naděje pro dospělé. [Standardization of the Czech version of the Snyder´s Adult dispositional hope scale]. Psychologie a její kontexty. 2016;7(1):109–123. Czech. | ||

Schrank B, Amering M, Hay AG, Weber M, Sibitz I. Insight, positive and negative symptoms, hope, depression, and self-stigma: a comprehensive model of mutual influences in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2014;23(3):271–279. | ||

Smith MJ, Cloninger CR, Harms MP, Csernansky JG. Temperament and character as schizophrenia-related endophenotypes in non-psychotic siblings. Schizophr Res. 2008;104(1):198–205. | ||

Guillem F, Bicu M, Semkovska M, Debruille JB. The dimensional symptom structure of schizophrenia and its association with temperament and character. Schizophr Res. 2002;56(1):137–147. | ||

Gonzalez-Torres MA, Inchausti L, Ibáñez B, et al. Temperament and character dimensions in patients with schizophrenia, relatives, and controls. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(7):514–519. | ||

Kurs R, Farkas H, Ritsner M. Quality of life and temperament factors in schizophrenia: comparative study of patients, their siblings and controls. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(2):433–440. | ||

Bora E, Veznedaroglu B. Temperament and character dimensions of the relatives of schizophrenia patients and controls: the relationship between schizotypal features and personality. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(1):27–31. | ||

Fresán A, León-Ortiz P, Robles-García R, et al. Personality features in ultra-high risk for psychosis: a comparative study with schizophrenia and control subjects using the Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised (TCI-R). J Psychiatr Res. 2015;61:168–173. | ||

Hori H, Noguchi H, Hashimoto R, et al. Personality in schizophrenia assessed with the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI). Psychiatry Res. 2008;160(2):175–183. | ||

Cortés MJ, Valero J, Gutiérrez-Zotes JA, et al. Psychopathology and personality traits in psychotic patients and their first-degree relatives. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(7):476–482. | ||

Ritsher JB, Otilingam PO, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121(1):31–49. | ||

Boyd JE, Adler EP, Otilingam PG, Peters T. Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) Scale: a multinational review. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(1):221–231. | ||

Ocisková M, Praško J, Kamarádová D, et al. Self-stigma in psychiatric patients – standardization of the ISMI scale. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014;35(7):624–632. | ||

Češková E, Přikryl R, Pěč O. Schizofrenie u dospělých. [Schizophrenia in adults]. In: Raboch J, Uhlíková P, Hellerová P, Anders M, Šusta M, editors. Psychiatrie. Doporučené postupy psychiatrické péče IV. Praha: Psychiatrická společnost ČSL JEP; 2014:44–51. Czech. | ||

EMEA. 2002. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003526.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2009. | ||

Bewick V, Cheek L, Ball J. Statistics review 14: logistic regression. Crit Care. 2005;9(1):112–118. | ||

Nathans LL, Oswald FL, Nimon K. Interpreting multiple linear regression: a guidebook of variable importance. Prac Assess Res Eval. 2012;17(9):1–19. | ||

Güçlü O, Erkiran M, Aksu EE, Aksu H. Şizofrenide Sosyal Bunalti Bozukluğu Eştanisi; Sosyodemografik ve Klinik Özellikler ile Ilişkisi. [Clinical correlates of social anxiety disorder comorbidity in schizophrenia]. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2012;23(1):1–8. Turkish. | ||

Braga RJ, Reynolds GP, Siris SG. Anxiety comorbidity in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(1):1–7. | ||

Lysaker PH, Salyers MP. Anxiety symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: associations with social function, positive and negative symptoms, hope and trauma history. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116(4):290–298. | ||

Cloninger CR, Svrakić DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(12):975–990. | ||

Cloninger CR. A unified biosocial theory of personality and its role in the development of anxiety states. Psychiatr Dev. 1986;4(3):167–226. | ||

Cloninger CR, Dragan M, Svrakić DM. Personality disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan & Shaddock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009;2197–2241. | ||

Argyle N. Panic attacks in chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:430–433. | ||

Svrakić DM, Draganić S, Hill K, Bayon C, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Temperament, character, and personality disorders: etiologic, diagnostic, treatment issues. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(3):189–195. | ||

Cloninger CR. Temperament and personality. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:266–273. | ||

Vrbova K, Prasko J, Holubova M, et al. Self-stigma and schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016.24;12:3011–3020. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.