Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 16

Clinical Characteristics, Prenatal Diagnosis and Outcomes of Placenta Accreta Spectrum in Different Placental Locations: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Received 13 September 2023

Accepted for publication 22 January 2024

Published 26 January 2024 Volume 2024:16 Pages 155—162

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S439654

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

Xiaoling Feng,1 Xun Mao,1 Jianlin Zhao2,3

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, 401120, People’s Republic of China; 2The Department of Obstetrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, 400016, People’s Republic of China; 3Chongqing Key Laboratory of Maternal and Fetal Medicine, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, 400016, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Jianlin Zhao; Xun Mao, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Objective: To explore the prenatal diagnosis, clinical characteristics, and perinatal outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum in different placental locations.

Methods: This was a retrospective cohort study. Pregnant women who delivered at two tertiary referral hospitals from January 2013 to December 2022 and were ultimately pathologically diagnosed with placenta accreta spectrum were included. They were divided into three groups based on different placental locations (anterior, posterior, and lateral wall/fundus). The differences in prenatal diagnosis, clinical characteristics, and perinatal outcomes among the three groups were compared.

Results: There were 115,470 deliveries in a ten-year period at the two hospitals, and 118 case patients were confirmed to have a pathologically diagnosed placenta accreta spectrum. The posterior placenta group had a lower rate of placenta previa (76.9% vs 94.9% vs 100%, p< 0.05) and a higher gestational age at delivery (36.4± 2.45 vs 34.91± 1.76 vs 34.31± 3.41, p< 0.05) compared to the other two groups. The anterior placenta group had a significantly higher rate of invasive (increta/percreta) form placenta accreta spectrum (81.4% vs 36.5% vs 28.6%, p< 0.05) and planned cesarean section (96.6% vs 80.8% vs 71.4%, p< 0.05) compared to the other two groups. In terms of prenatal diagnosis, the anterior placenta group had a significantly higher rate of placenta accreta spectrum prenatal suspicion rate compared to the other two groups (86.4% vs 36.5% vs 57.1%, p< 0.05). The posterior placenta group had a lower rate of preoperative abdominal aortic balloon placement compared to the other two groups (5.8% vs 28.8% vs 28.6%, p< 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups in primary perinatal outcomes, though the anterior placenta group had a longer postoperative hospital stay.

Conclusion: The prenatal diagnosis rate and proportion of invasive form of placenta accreta spectrum occurring in non-anterior placenta are relatively lower than anterior placenta. There were no significant differences in major perinatal outcomes among the three groups.

Keywords: placenta accreta spectrum, placenta location, clinical characteristics, perinatal outcomes

Introduction

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) refers to a group of conditions in which the placenta abnormally invades or penetrates the uterine wall, and even invades adjacent organs.1 Depending on the degree of invasion, PAS can be classified into placenta accreta, placenta increta, and placenta percreta. With the increasing rate of cesarean section (CS) worldwide, the incidence of PAS has significantly risen.2 PAS is associated with severe complications such as postpartum hemorrhage, preterm birth, organ damage, and uterine hysterectomy.3 Therefore, early detection and adequate preparation before delivery can significantly improve perinatal outcomes.

Although studies have identified a history of prior cesarean section (CS) and placenta previa (PP) as major risk factors for PAS, the overall prenatal diagnosis rate of PAS remains relatively low.4 Prenatal diagnosis of PAS mainly relies on the identification of ultrasound signs and risk factors by clinicians. However, for these missed cases, studies have suggested that they may not have major typical risk factors, which can affect clinicians’ judgment.5–7 Some studies have indicated that placental position may affect the prenatal diagnosis of PAS.8,9 However, there is limited research on whether there are differences in clinical characteristics and perinatal outcomes among PAS cases with different placental positions.

The main objective of this study is to explore the prenatal diagnosis rate, clinical characteristics, and perinatal outcomes of PAS based on different placental positions, and to provide more data support for improving the prenatal diagnosis rate and perinatal outcomes of PAS in this specific type.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed in two university-based tertiary referral centers from Jan 1, 2013, to Dec 31, 2022. To identify all cases, data were extracted from the electronic health record. Patients were included if they had a delivery at 1 of the 2 hospitals, had a hysterectomy performed at the delivery, and had a pathology-confirmed diagnosis of PAS. Twin pregnancies were included in this study. This study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee of these two hospitals.

Antepartum PAS suspicion was based on any PAS ultrasound imaging modalities relying on antenatal diagnosis of the experienced ultrasonographers or maternal fetal medicine specialist. For pregnant women who were not suspected for PAS, subsequent prenatal management would be carried out as guideline.10 The placental positions were classified into anterior placenta group, posterior placenta group, and lateral/fundal placenta group based on ultrasound evaluation.

The use of abdominal aortic balloon is limited to cases where PAS is suspected prenatally. Additionally, the abdominal aortic balloon is suitable for severe cases of PAS. We consider severe PAS if the case meets at least three of the following five ultrasound criteria: (1) Loss of the clear zone refers to the absence or irregularity of the hypoechoic layer in the myometrium beneath the placental bed; (2) Placental lacunae, defined as the presence of numerous cavities that often exhibit turbulent flow, visible on grayscale or color Doppler ultrasound; (3) Bladder wall interruption, defined as the loss or interruption of the bright bladder wall, which is the hyperechoic band or line between the uterine serosa and the bladder lumen; (4) Uterovescical hypervascularity, defined as a significant amount of color Doppler signal observed between the myometrium and the posterior wall of the bladder. This includes vessels that appear to extend from the placenta, traverse the myometrium, extend beyond the serosa, and reach the bladder or other organs, often running perpendicular to the myometrium; (5) Increased vascularity in the parametrial region, refers to the presence of hypervascularity extending beyond the lateral uterine walls and involving the region of the parametria.

Detailed demographic data such as maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, gravidity and parity, multiple gestation, in vitro fertilization, PP, and PAS-related history were included. Other basic characteristics such as delivery mode and delivery weeks were also recorded. We categorized PAS diagnoses into noninvasive (accreta) or invasive (increta or percreta) since available data showed lower morbidity for placenta accreta and similar morbidity for the two invasive forms.11,12 Perinatal outcomes mainly included estimated blood loss in 24h, blood products transfusion, abdominal aorta balloon block, abdominal and pelvic organ injuries, ICU admission and postoperative hospital stay. All the data were double-checked by trained research personnel.

Statistical Analysis

The normality of continuous variables was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally distributed data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed data were presented as median (P25, P75). Categorical data were presented as counts (%). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data.

Due to the small sample size of only seven cases in the lateral wall/fundus group, further pairwise comparisons were only conducted between the anterior and posterior groups for selected measures showing statistical significance in the cross-tabulations. Two-tailed probability value of P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were performed with SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 26, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

General Characteristics

There were 115,470 deliveries in a ten-year period at the two hospitals. After reviewing pathology reports, 118 case patients were confirmed to have a diagnosis of PAS. The distribution of placental location on ultrasound was as follows: 50% anterior, 44.1% posterior, and 5.9% lateral wall/fundus.

Table 1 compared the basic characteristics among the three groups. The overall prenatal suspicion rate of PAS in these two centers was 62.7% (74/118), but there were significant differences among the three groups. Our results showed that the prenatal diagnosis rate in the anterior placenta group was 86.4% (51/59), while the rate in the posterior placenta group was only 36.5% (19/52), the lowest among the three groups.

|

Table 1 Baseline Characteristics in Three Groups |

In the comparison of basic clinical characteristics, although the incidence of PP was high in all groups, the posterior placenta group had a lower rate of PP compared to the other two groups (76.9% vs 94.9% vs 100%). In comparison to the severity of invasion, the incidence of invasive PAS was significantly higher in the anterior placenta group compared to the other two groups (81.4% vs 36.5% vs 28.6%). There were also significant differences in the mode of delivery among the three groups, with the posterior and lateral wall/fundus groups having a significantly higher rate of emergency CS compared to the anterior placenta group (17.3% vs 28.6% vs 3.4%). Additionally, the gestational age at delivery in the posterior placenta group was higher than the other two groups (36.4±2.45 vs 34.91±1.76 vs 34.31±3.41). There were no significant statistical differences among the three groups in other basic characteristics.

Comparison of Prenatal Diagnostic Rate Based on Placental Location and Severity of Invasion

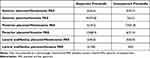

Based on different placental locations and the severity of placental invasion, we further divided these cases into six groups and calculated the prenatal diagnostic rates for each group (Table 2). Firstly, for the same placental location, the prenatal diagnostic rates for invasive (increta/percreta) PAS cases were significantly higher than those for noninvasive (accreta) PAS (93.8% vs 54.6% in anterior placenta, 68.4% vs 18.2% in posterior placenta, 100% vs 40.0% in lateral wall/fundus placenta). Secondly, for cases with the same degree of invasion, the prenatal diagnostic rates were significantly higher in the anterior placenta group and lateral wall/fundus groups compared to the posterior groups (54.6% vs 40.0% vs 18.2% in noninvasive cases, 93.8% vs 100.0% vs 68.4% in invasive cases).

|

Table 2 Prenatal Diagnostic Rate Based on Placental Location and Severity of Invasion |

Comparison of Perinatal Outcomes

Table 3 showed the perinatal outcomes of the three groups. There were no significant differences in the primary perinatal outcomes among the three groups. However, the anterior placenta group and lateral wall/fundus groups had a significantly higher rate of preoperative abdominal aortic balloon block placement compared to posterior groups (28.8% vs 28.6% vs 5.8%), and the anterior placenta group had the shortest operating time among the three groups (122.71±28.47 vs 137.75±23.18 vs 141.43±38.91). Although there were statistically significant differences in postoperative length of stay among the three groups, the median difference in length of stay was just 1 day.

|

Table 3 Perinatal Outcomes in Three Study Groups |

Statistically significant features in Tables 1 and 3 were further compared pairwise between the anterior and posterior placenta groups. The results also showed significant differences in all these features in the pairwise comparisons.

Discussion

Consistent with other research,8,9 our results indicated that the prenatal suspicion rate of PAS varies significantly among different placental locations. The anterior placenta group had the highest rate (86.4%), while the posterior placenta group only has a rate of 36.5%. Furthermore, a more detailed comparison revealed that, among cases with the same degree of invasion, the prenatal diagnostic rate for posterior placenta was also the lowest. There may be multiple reasons for this difference. Firstly, placental location has a significant impact on the prenatal identification of PAS. As prenatal diagnosis of PAS mainly relies on observing the placental morphology and assessing the abundance of blood flow within the placenta and between the placenta and uterine wall through ultrasound, the image quality may be affected when the ultrasound needs to pass through fetal to observe the placenta. Secondly, the presence or absence of PP can also affect the prenatal suspicion of PAS. In our study, the anterior placenta group had a significantly higher rate of PP compared to the posterior placenta group (94.9% vs 76.9%). Previous studies had shown that the prenatal diagnosis rate of PAS significantly decreased when absenting of PP.5,13 The absence of PP may contribute to missed diagnoses as it can lead to a relaxation of vigilance by physicians. Lastly, our results showed that the percentage of non-invasive form PAS (placenta accreta) is significantly higher in the non-anterior placenta group. Being the mildest form of PAS with shallow implantation and smaller area, placenta accreta is inherently difficult to diagnose prenatally. Even in the anterior placenta group, which has the easiest observation of the placenta, only 6 out of 11 cases of placenta accreta were suspected prenatally in our study, resulting in a prenatal diagnosis rate of 54.5%. Each of the aforementioned factors can contribute to the difficulty in prenatal diagnosis of PAS, especially when multiple factors may be present in a certain case, making prenatal diagnosis even more challenging. Improving the prenatal diagnosis rate for PAS cases without typical high-risk factors may be a new direction for future research.

Our results showed significant differences in the mode of delivery among these groups. The planned CS rate was significantly higher in the anterior placenta group, while the emergency CS rate was significantly higher in the other two groups. Additionally, the gestational age at delivery was significantly higher in the posterior placenta group than the other two groups. The differences in the prenatal suspicion rate and the rate of PP may contribute to the differences in the mode of delivery and gestational age at delivery. Pregnant women who were suspected of having PAS or PP may be more inclined to opt for planned CS earlier in their pregnancy. On the other hand, pregnant women with normal placental position and no suspicion of PAS, as they do not have an indication for CS, were advised to wait for spontaneous labor. Therefore, the likelihood of subsequent emergency CS was higher in these cases.

There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups in terms of primary perinatal outcomes, mainly including estimated 24-hour blood loss, transfusion of blood products, abdominal and pelvic organ injuries, and ICU admission rate. However, Jang et al14 and Morgan et al8 suggested that the perinatal outcomes of non-anterior placenta with PAS were better than those of the anterior placenta group. Additionally, a recent study had shown that multidisciplinary management during pregnancy could significantly improve the perinatal outcomes of cases with suspected PAS, even with a significantly higher proportion of invasive PAS compared to the control group.15 In fact, due to the limited research available currently, there is still controversy regarding the perinatal outcomes of different placental positions after the occurrence of PAS. The conclusions drawn from these studies also need to be validated through larger prospective studies with a greater sample size.

Currently, studies suggested that the use of preoperative abdominal aortic balloon could improve perinatal outcomes,16 but our study did not yield similar results, possibly due to the smaller sample size. However, our results showed that the operating time in the anterior placenta group is shorter than the other two groups, even though the proportion of invasive cases were higher in the anterior placenta group. It may be related to the use of preoperative abdominal aortic balloon, as this precaution can briefly control bleeding during the surgery and provide the surgeon with a clearer surgical view, thereby shortening the surgical time.17

Strengths and Limitations

The main advantage of this study is that all cases included had pathological report, which made the diagnosis and grading of PAS more accurate and minimized false positives and bias. Our samples were collected from two tertiary hospitals, which lessened the likelihood of uniform treatment of the diagnosis and increased the likelihood of management variation, which may better approximate clinical care.

Our study has limitations. Firstly, we were limited by the retrospective nature of this study. Secondly, due to the relatively small sample size in the lateral wall/fundus group, we did not proceed with further pairwise comparisons between this group and the other two groups. Furthermore, we found more cases managed conservatively without hysterectomy, which were not included in the study due to the lack of pathological reports. However, we believe that the importance of cases requiring hysterectomy is far greater than those that can be managed conservatively. Lastly, we reviewed data from the past decade to obtain as many cases as possible, and the collected variables may have changed with the development of surgical and ultrasound techniques, which may have an impact on our results.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that non-anterior placenta, especially posterior placenta combined with PAS, had lower rates of PP and invasive PAS cases compared to the anterior placenta group. These differences, combined with the impact of placental position, may significantly reduce the prenatal suspicion rate of PAS. Therefore, greater vigilance is needed in clinical practice for this type of PAS. On the other hand, although the prenatal suspicion rate of PAS was lower in non-anterior placenta group, there were no difference in the primary perinatal outcomes compared to the anterior placenta group. However, due to the small sample size in this study, further validation of this conclusion is needed.

Abbreviations

PAS, placenta accreta spectrum; BMI, body mass index; CS, cesarean section; RBC, red blood cell; ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not available.

Data Sharing Statement

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University and The Third Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. As this is a retrospective research, informed written consent was exempted but oral permission was obtained from all individual participants before embarking on this study. Ethics committees approved the verbal consent process.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81971406, 81871185), The 111 Project (Yuwaizhuan (2016) 32), Chongqing Science & Technology Commission (cstc2021jcyj-msxmX0213), Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KJZD-K202100407), Chongqing Health Commission and Chongqing Science & Technology Commission (2021MSXM121, 2020MSXM101) and the Cultivation Funding of The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (PYJJ-2019-220). No funding sources had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the report.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Cahill AG, Beigi R, Heine RP, Silver RM, Wax JR.; Society of Gynecologic O, American College of O, Gynecologists. Placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(6):B2–B16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.042

2. Jauniaux E, Ayres-de-Campos D, Diagnosis FPA; Management Expert Consensus P. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: introduction. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140(3):261–264. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12406

3. Jauniaux E, Ayres-de-Campos D, Langhoff-Roos J, et al. FIGO classification for the clinical diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146(1):20–24. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12761

4. Carusi DA. The placenta accreta spectrum: epidemiology and risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(4):733–742. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000391

5. Mulla BM, Weatherford R, Redhunt AM, et al. Hemorrhagic morbidity in placenta accreta spectrum with and without placenta previa. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300(6):1601–1606. doi:10.1007/s00404-019-05338-y

6. Tinari S, Buca D, Cali G, et al. Risk factors, histopathology and diagnostic accuracy in posterior placenta accreta spectrum disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57(6):903–909. doi:10.1002/uog.22183

7. Palacios-Jaraquemada JM, D’Antonio F. Posterior placenta accreta spectrum disorders: risk factors, diagnostic accuracy, and surgical management. Mater Fetal Med. 2021;3(4):268–273. doi:10.1097/FM9.0000000000000124

8. Morgan EA, Sidebottom A, Vacquier M, Wunderlich W, Loichinger M. The effect of placental location in cases of placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(4):357 e1–357 e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.07.028

9. Abotorabi S, Chamanara S, Oveisi S, Rafiei M, Amini L. Effects of placenta location in pregnancy outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS): a retrospective cohort study. J Family Reprod Health. 2021;15(4):229–235. doi:10.18502/jfrh.v15i4.7888

10. Subgroup O. Guideline of preconception and prenatal care. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2018;53(1):7–13. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-567X.2018.01.003

11. Brookfield KF, Goodnough LT, Lyell DJ, Butwick AJ. Perioperative and transfusion outcomes in women undergoing cesarean hysterectomy for abnormal placentation. Transfusion. 2014;54(6):1530–1536. doi:10.1111/trf.12483

12. Marcellin L, Delorme P, Bonnet MP, et al. Placenta percreta is associated with more frequent severe maternal morbidity than placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):193 e1–193 e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.04.049

13. Carusi DA, Fox KA, Lyell DJ, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum without placenta previa. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(3):458–465. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003970

14. Jang DG, We JS, Shin JU, et al. Maternal outcomes according to placental position in placental previa. Int J Med Sci. 2011;8(5):439–444. doi:10.7150/ijms.8.439

15. Erfani H, Fox KA, Clark SL, et al. Maternal outcomes in unexpected placenta accreta spectrum disorders: single-center experience with a multidisciplinary team. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(4):337 e1–337 e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.05.035

16. Yin H, Hu R. Outcomes of prophylactic abdominal aortic balloon occlusion in patients with placenta previa accreta: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):502. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-04837-2

17. Liu Y, Shan N, Yuan Y, Tan B, Qi H, Che P. The clinical evaluation of preoperative abdominal aortic balloon occlusion for patients with placenta increta or percreta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(25):6084–6089. doi:10.1080/14767058.2021.1906219

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.