Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

Between Collectivism and Individualism – Analysis of Changes in Value Systems of Students in the Period of 15 Years

Authors Czerniawska D , Czerniawska M , Szydło J

Received 21 July 2021

Accepted for publication 15 October 2021

Published 14 December 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 2015—2033

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S330038

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Dominika Czerniawska,1 Mirosława Czerniawska,2 Joanna Szydło2

1Faculty of Science, Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands; 2Faculty of Engineering Management, Bialystok University of Technology, Bialystok, Poland

Correspondence: Joanna Szydło Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Introduction: The publication deals with the description of selected aspect of young people’s mentality, ie their systems of values. The research was conducted four times: in 2003 (325 respondents), in 2008 (379 respondents), in 2013 (368 respondents), and in 2018 (371 respondents) on students of the Bialystok universities. An attempt was made to establish if in the period of the fifteen years between the first survey and the last surveys one could observe changes in the mentality in the desired direction – from the point of view of political transformations – from “collectivism” to “individualism”. The way of understanding values was adopted from Rokeach’s theory.

Methods: The Rokeach Value Survey was used to study the system of values.

Results: The comparative analysis of the value preferences indices across all surveys (survey by survey) has not confirmed proposed hypothesis. It has been shown that the value system has changed towards individualism over fifteen years (when comparing surveys from year 2003 and 2018). Contradictory to the expectations, the most individualistic system of values was presented in survey group in 2008, and not in 2018.

Conclusion: There was no increase in rates of preference for individualistic values “from study to study”. The trajectories of changes in value systems turned out to be much more complex (and thus more difficult to describe).

Keywords: values of youths, Rokeach’s value theory, collectivism-individualism, political transformations

Introduction

Values are a constant concern in social sciences. Research seeks to explain what factors determine the formation of value systems, what their relationship with other constructs (eg mentality) is and whether and on what basis they determine behaviour. Attention is paid to the cultural determinants of value systems. Values are then considered intersubjectively: they become common ideas that are replicated and internalized by an individual. The educational environment and especially parents play a special role in this process. To a large extent, value profiles are passed on by institutions – religious, political and educational – within which an individual functions. The study of values is important from a management perspective. They constitute a context for considerations involving organisational change, corporate social responsibility, leadership, entrepreneurship, the creation of organisational structures and cultures, and organisational behaviour. The axiology of individuals is also considered in the context of individual characteristics. This takes into account a socio-economic status, age, marital status, education, occupation, gender, dominant needs and personality traits. The system of values is also conditioned by events, especially those that were important in human life and rooted in autobiographical memory. It then contributes to the understanding of mental processes which are connected with the evaluation, justification and choice of acts.1–32

Values are linked to political and economic variables, broader social issues and interpersonal relationships.33–43

Interest in the value construct has increased during the transition period in Central and Eastern European countries. The process of political change is multidimensional, and its final course is determined by the interaction between organisational-institutional and mental-cultural levels. The effect of this interaction – as has been shown in numerous studies – involved transformations in the sphere of mentality of societies in the region, which manifested itself in changes of value systems.17,44–58

How stable is the value system in the course of an individual’s lifetime? In general, values are considered to be a relatively stable “mental construct” which has motivational properties and affects emotional states.59 It is a result of assimilation – more uncritical or more selective – of a value hierarchy belonging to a culturally defined community. However, the process of change may activate in adult life when a person notices that other people are axiologically different or when he/she realises that the society expects something different from him/her. Then it becomes a requirement to adapt to the new reality, which entails a different interpretation of values and a new definition of priorities. It becomes necessary to redefine the attitude towards oneself and interpersonal relationships, emotional closeness and security, self-fulfilment and a sense of achievement. This redefinition – although desirable from the point of view of, for example, political change – can become a “painful” process for many people. This is because values are a key component of mentality, they are strongly linked to the “I” and form part of an ideal self-image.

Three decades ago, the Polish society faced radical political changes. At that time, an institutionally different axiology was promoted, ie one that facilitated functioning in conditions of liberal democracy and free market economy. The new configurations of values were to constitute individualistic mentality (dominant in Western countries which constituted a model of political changes) as an opposition to the existing collectivist mentality. Individualistic mentality and the values constituting its expression were to stimulate acts desired from the point of view of the political system: freeing oneself from group dependence, focusing on the realization of tasks, one’s own success and competences, striving for freedom, autonomy and creativity. According to Bokszański (2007), “the nature of the modern economy and the structure of contemporary political systems incline towards treating the development of individualism as a condition for the progress of modernisation”60 (p. 145).

We do not know the results of longitudinal studies describing trends in the change of value systems of people whose adult took course in the last 30 years (more often, however, the focus was on adolescence, e.g.).61,62 This would undoubtedly provide important information on whether changes in value preferences all he more reflect the “logic of the system” or just the “logic of development”, ie typical age-related transformations. The subject literature presents mainly research which described the hierarchy of values of a once diagnosed group (which makes it impossible to capture these changes). However, when the focus was made on the comparative analysis of value systems of different groups differently localized in time (which makes it possible to capture changes), usually the measurements were not cyclical. Nevertheless, generalising the research results collected by different authors22,30,63–102 cf. overview of research in: Czerniawska,103,104 a general regularity should be observed: in the Polish society such “stabilisation” values as “health”, “family”, “work”, “prosperity” dominate over the values of progress and development, advancement and transformation. The change of value systems varies in different social groups and depends among other things on factors such as age and level of education. Fifteen years ago, Skarżyńska68 expressed a view that even if traditional, community-related values are still observed in the Polish society, young and educated people exhibit a “pro-developmental potential”. It is this capital that gives hope for the modernisation and democratisation of Poland. Has the axiology of the young Polish generation really changed in this direction?

The studies presented in this article involve a comparative analysis of value systems. They were conducted in cycles (every 5 years) – in 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018 – and covered successive generations of young students. From the four diagnosed groups, the members of the first and second were born before 1989 (about 6–7 or 1–2 years), ie in the reality of the former political and economic system. The members of the third and fourth group were born after 1989 (about 2–3 or 7–8 years), which means that they took – although to varying degrees – socialization patterns from the new reality and freed themselves – at least to some extent – from the old historical-cultural context. Interest was drawn to answering the question whether together with the “taming” of a new system in the country, the axiological orientation of the students is really changing to a more individualistic one? If such a process actually takes place, then each of the following research groups should appreciate individualistic values higher and the collectivist values lower, ie those that characterized the society existing in the former system. It could then be claimed that there emerges adaptation in the axiological sphere to macro-social events.

In this study, the concept of Milton Rokeach’s values was adopted.105 A value is treated as an abstract notion, “an enduring belief that a specific mode of conduct or end-state of existence is personally or socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end-state of existence”105 (p. 5). Values differ in the level of acceptance and form a (more or less) structured system which is defined as “an enduring organization of beliefs concerning preferable modes of conduct or end-states of existence along a continuum of relative importance” (p. 5). Adult people have such complex cognitive processes that they can estimate the relative importance of values. Since a value is a general criterion determining preferences, man can respond to reality and his/her own experiences. This involves seeking to understand reality in more general terms. Values are transcendent with regard to the situation, they guide the assessment and selection of behaviour. They arise from life experiences that are acquired through interaction with the environment. A person integrates information about values in separate cognitive patterns in a self-determined way and fully specified their meaning (cf.103).

Rokeach distinguishes two types of values: terminal values, which define end-state of existence, and instrumental values, which define specific mode of conduct. Among the terminal values, there are interpersonal (focusing on society) and intrapersonal (focusing on the individual). Among instrumental values, there are competency values (more personal and related to self-acceptance) and moral values (more social and related to interpersonal relationships). The author also assumes that terminal and instrumental values bear relationships of a functional and cognitive nature.

Research Problem and Hypotheses

During the transformation process in Poland, it was emphasised that it is easier to change the system than the culturally determined mentality of society. This is because it is a conservative and “opposing” creation.106 The question arises as to how the changes in the mentality of the society are “stretched” over time, and whether the compliance with the assumed direction, ie “from collectivism – to individualism” is actually revealed. It should be stressed that values are an important – if not the most important – component of mentality. On the basis of their analysis, it is possible to make conclusions on collectivist or individualistic attitudes – their increase or decrease.

The research – as indicated above – is of a comparative nature. It was carried out in 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018, using the same tool, ie the Rokeach Value Survey (RVS). The aim was to establish empirically, over what period of time and in what direction changes in value systems become apparent. Is it really possible to observe a devaluation of the importance of collectivist values that made a “peaceful and harmonious” individual dependent on the group and an increase in the acceptance of individualistic values, facilitating adjustment to the new system? The following hypothesis was put to test: the later the research was carried out, the relatively lower preference indicators were obtained for collectivist values and the relatively higher ones for individualistic values. The main hypothesis was broken down into specific hypotheses (the years separating the studies, ie 5, 10 and 15, were included):

H1. The correlations indicated in the main hypothesis are observable when comparing groups at a 5-year distance, ie: H1a. groups diagnosed in 2003 and 2008. H1b. groups diagnosed in 2008 and 2013. H1c. groups diagnosed in 2013 and 2018. H2. The correlations indicated in the main hypothesis are observable when comparing groups at a 10-year distance, ie: H2a. groups diagnosed in 2003 and 2013. H2b. groups diagnosed in 2008 and 2018. H3. The correlations indicated in the main hypothesis are observable when comparing groups at a 15-year distance, ie: groups diagnosed in 2003 and 2018.

The verification of the above hypotheses will allow to describe trends in the change of values over a period of 15 years (they take into account different time frames). Statistically significant differences in the preference of individual values were analysed, and then their specificity was taken into account: collectivist or individualistic (the classification of values is given below). A shift “towards individualism” was considered to be a configuration of results in which individualistic values (or at least most of them) were preferred relatively higher (and statistically significantly) in the later survey. A shift “towards collectivism” was considered to be a result configuration in which collectivist values (or at least the majority of them) were preferred relatively higher (and statistically significantly) in a later survey. Using the RVS, it is not possible to obtain an integrated (single) indicator of collectivist values and an integrated (single) indicator of individualist values. The analysis of the results should therefore take into account the (individualistic or collectivist) specificity of the values.

While considering the problem of axiological transformation in the post-transformation period, it is justified to undertake research into the young generation, which grew up in the new political conditions. These conditions were not equally “favourable” in all regions of the country. According to Sadowski,107 the North-East of Poland is special because the political changes were less effective there, there emerged (at least at the end of the last century) a stronger community character of interpersonal relations and a lack of values conducive to competition and striving for success. It therefore seems particularly interesting to “trace” changes in the value system of the studying youth in the region.

The results of studies from 2003, 2008 and 2013 were previously presented by one of the authors.103,104 The comparative analyses make it necessary to refer to these publications and include their fragments. They relate to: hypotheses (the same for all four studies), characteristics of the research tool (the same tool was used), division of values into collectivist and individualistic, characteristics of research groups from 2003, 2008 and 2013 and comparison of their value systems.

Method

Study design: The survey was questionnaire-based (The Rokeach Value Survey). This made it possible to collect data on value systems in years 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018.

Research group: The study involved 1443 people, of whom 325 (22.52%) – in 2003, 379 (26.26%) – in 2008, 368 (25.50%) – in 2013 and 371 (25.72%) – in 2018. Four groups were unified in terms of:

- field of studies: about 50% of the respondents were students of pedagogy at the University of Bialystok and about 50% of the respondents – students of management at Bialystok University of Technology;

- mode of studies: full-time studies;

- educational level: first-, second- and third-year students;

- gender: women’s prevalence (approximately 80%);

- age: about 90% of the respondents were students aged 20–21 years.

Taking into account the features of the four research groups presented above, it can be assumed that they are characterised by a similar range of knowledge of socio-political reality, comparable intellectual level, similar – related to the field of study and development period – interests, as well as similar interpersonal experiences (social relations). Information relating to the similarity of research groups is important especially when comparative analyses are made. However, the described groups differ in terms of “social time”, quality of experienced facts and events. Another differentiating factor is the condition of free market economy and liberal democracy over the past years as well as the ideas promoted by successive governments.

The survey was anonymous and was conducted during classes at the university. The respondents’ participation in the survey was voluntary. They could resign from participation at any time. The respondents gave verbal consent in the presence of witnesses. The respondents were informed in advance that the research concerned beliefs about themselves. The survey was conducted during a 0.5-hour meeting (groups of 20–25 people).

Material: The Rokeach Value Survey (RVS), well-known in the literature, was used in the study. Its adaptation for the Polish context was carried out by Brzozowski (1989). In order to measure the relative importance of values, Rokeach selected eighteen terminal values (they determine end-states of existence) and eighteen instrumental values (they determine modes of conduct) and placed them on two separate scales. The surveyed ordered these values by assigning them appropriate ranks. Rank “1” was the highest preferable value, rank “18” was the lowest preferable value. The paper version of RVS was used.

From the point of view of the formulated research problem, it is necessary to clarify which values are hidden in the constellation “individualism – collectivism”. Detailed rules of classification and their justification can be found in earlier publications of one of the authors.103,104 Helpful in this respect were, among others, theoretical studies and analyses conducted by Schwartz108–110 and Brzozowski.111,112

Based on the Rokeach Value Survey, collectivist values were associated with (t – terminal values, i–instrumental values):

- the protection of the welfare of all people and those with whom an individual interacts directly (the welfare of the group to which the individual belongs): “a world at peace” (t17), “equality” (t2), “helpful” (i8), “honest” (i9), “forgiving” (i7), “loving” (i14), “responsible” (i17);

- the security of identity groups and respect for tradition/religion: “family security” (t4), “national security” (t9), “salvation” (t11);

- balanced social views, intrapersonal and interpersonal harmony: “wisdom” (t16), “inner harmony” (t7), “self-controlled” (i18), “clean” (i5) “polite” (i16), “obedient” (i15), “mature love” (t8), “true friendship” (t15).

Individualist values are those associated with (t – terminal values, i–instrumental values):

- social status, prestige and personal (including material) success: “social recognition” (t14), “self-respect” (t12), “sense of accomplishment” (t13), “ambitious” (i1), “a comfortable life” (t1);

- freedom of choice, independence of thought and action, intellectual competence: “freedom” (t5), “independent” (i11), “courageous” (i6), “imaginative” (i10), “broad-minded” (i2), “capable” (i3), “intellectual” (i12), “logical” (i13);

- hedonism and the need for stimulation (interesting, pleasant, exciting life): “happiness” (t6), “cheerful” (i4), “pleasure” (t10), “an exciting life” (t3), “a world of beauty” (t18).

Research Results

On the basis of the data collected in the course of four studies, an attempt has been made to answer the question of whether 5, 10, 15 years is a sufficient period for axiological changes to become apparent. The differentiation of value preferences was interpreted in the dimension “individualism – collectivism”.

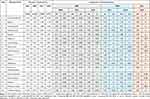

In the four sample groups considerable significance is attributed to collectivist values (cf. Tables 1 and 2, Figures 1 and 2). They are associated with family (“family security”), protection of people’s welfare, emotional relations, interpersonal and intrapersonal harmony (“responsible”, “honest”, “helpful”, “loving”, “mature love”, “true friendship”, “wisdom”, “inner harmony”). This conclusion is consistent with the statement made by Dyczewski74 nearly a quarter of a century ago: the need for being surrounded by close people, security and stabilization outrank the need for self-accomplishment and expression of individuality. Quite high rates are given to individualistic values: “self-respect”, “happiness”, “freedom” and “ambitious” (the average ranks of the listed values are between 2 and 9). Other individualistic values are placed low in the system (from 9th to 16th rank). It should be emphasized that among them there are “pro-development” ones, the meaning of which was highlighted in the period of political transformation.68,93 According to Świda-Ziemba,89 they constitute a “capitalist ideology”, activate rivalry and competition. Achieving one’s life success becomes possible when skills and talents that distinguish an individual from other people are valued.

|

Table 1 Preferences for Terminal Values – Comparative Analysis of Research Results Obtained in 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018 |

|

Table 2 Preferences for Instrumental Values – Comparative Analysis of Research Results Obtained in 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018 |

|

Figure 1 Preference indicators of terminal values in groups of students surveyed in 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018. |

|

Figure 2 Preference indicators of instrumental values in groups of students surveyed in 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018. |

Focusing the analysis exclusively on value positions may lead to the conclusion that the systems are very stable. However, it should be borne in mind that with similar value positions in the system, relative differences in their preferences are revealed. Therefore, it is advisable to make an inter-group comparison of indicators. The analysis was carried out collectively for terminal and instrumental values (cf. Tables 1 and 2, Figures 1 and 2), taking into account the division into collectivist and individualistic values presented above.

Discussion

The political transformation in Poland was aimed at changing the broadly understood order and reached the ideological foundations of the system. Every ideology contains implicit or explicit links to a system of values. Polish society, its formal and informal institutions revealed such constellations of values which served to promote and legitimise the system. It was assumed that people – adapting to institutional requirements – would acquire values, transfer them to life situations and contribute to the creation of the system. On the other hand – and this should be clearly emphasised – people take a positive attitude to ideologies that are based on values they highly appreciate. They are perceived as correct, ethical and, consequently, they direct behaviour towards the realisation of the values contained in the ideology. Values legitimise ideologies, whereas political ideologies are rooted in values.103,105,113–116

In analysing value systems, it should be noted that they are not entirely “humble” towards liberal democracy and free market economy. It cannot be said, therefore, that the “taming” of the system goes in line with a clear-cut change in the value systems of the next generation of the studying youth “from collectivist to individualistic”.

When comparing value systems “from survey to survey” – ie over a period of 5 years – it can be observed that individualism in the axiological sphere was more pronounced in the second study (2008) compared to the first one (2003). There was a higher preference for individualistic values related to hedonism and success (but not cognitive values) and a lower preference for collectivist values related to security, balanced social views and inner harmony. This result is consistent with hypothesis H1a. When the surveys from 2008 and 2013 as well as 2013 and 2018 were compared, the differentiation was observed in a small number of values. Characteristically enough, the importance of collectivist values related to security increased “from survey to survey”. In the context of the above analysis the hypothesis H1b and H1c cannot be confirmed. Thus, no regular increase in preferences of individualistic values and decrease in preferences of collectivist values was observed (cf. main hypothesis). However, this conclusion does not apply to the comparison of the first two research groups (2003 and 2008, hypothesis H1a).

By verifying the main hypothesis, it is possible to take a different time horizon – ie 15 years – and compare the data collected in 2003 and 2018. It appears that in the last study the orientation of values changes to more individualistic in comparison to the first study. This allows to confirm the hypothesis H3. It should be emphasized that individualism increases primarily in the hedonistic-freedom sphere. It does not refer to cognitive competences (the exception is the “logical” value) although it is connected with the need for success. However, it seems appropriate to draw attention to the fact that the value system of students diagnosed in 2018 is characterised by a higher preference for collectivist values related to the family and its welfare.

Carrying out comparisons over a 10-year distance provides additional information. Comparing data from 2003 and 2013, statistically significant differences in preference of numerous values were noted. However, when their content was put to closer analysis, it was found that the differences did not indicate an advantage of individualistic or collectivist orientation. High preference was given to individualistic values related to hedonism, material prosperity, one’s own social position and success on the one hand, and collectivist values related to family security, interpersonal relations and pro-social attitudes on the other. This configuration of values does not allow to confirm the hypothesis H2a.

By making a comparison of the value systems diagnosed in 2008 and 2018, numerous differences in value preferences were also noted. However, their content characteristics are different. The group diagnosed in 2018 turned out to be – despite the assumptions verbalized in the hypothesis H2b – more collectivist than the group diagnosed in 2008. Individualistic values mostly lost their importance, while collectivist values, especially those related to security, gained in importance. At the same time, it should be noted that the value system in 2018 was “more collectivist” than in 2008, but “more individualistic” than in 2003.

The results described in the article cannot be generalised to the whole society, as the research group was composed of students coming from a specific region of Poland. It should be taken into account that changes in value systems depend on many factors – for example age, gender, education, occupational and social roles, social position and wealth – and may therefore proceed differently in different social groups. However, they can be confronted with the works of other authors (it should be noted, however, that in most studies conducted in Poland, the authors made one measurement and focused on analysing their position in the system). The theoretical part of the article presents the conclusion from the research on the value systems of the Polish society after the political transformation. According to it, the values of “stabilization” – such as: “health”, “family”, “work”, “prosperity” – dominate over the values of progress and development, advancement and transformation. Usually, the authors emphasise the attachment of Poles to collectivist values. This “attachment” was confirmed in the study presented in this article (many collectivist values occupy high positions in the system; the most important one is “family security”). Nevertheless, it was not identical over the 15-year period. In the light of the research results shown above, it can be concluded that the system of values “towards individualism” changes when comparisons include a longer time span, ie 15 years. However, when this distance is shorter, “surprises” appear. Such a “surprise” was primarily the group diagnosed in 2008, which was characterized by a higher preference for individualistic values (especially in relation to 2003 and 2018).

Although it is not fully justified to interpret the obtained research results by referring (only and exclusively) to changes in the political and economic condition of society, it is tempting to point out a certain parallel. It then becomes necessary to pose a question: what happened before 2008, ie when the examined youth was in its formation period and defined the significance of individual values in the system? It was a period in which the vision of “liberal Poland” was promoted quite strongly. This vision postulated a country accepting the rules of free market economy without limitations and the principle of individual responsibility for one’s own fate.92 At that time Poland accessed the European Union (2004) and joined the Schengen Agreement (2007). That was associated with certain hopes, especially in terms of integration with the affluent West. This 5-year-long period also saw a significant economic recovery and a drop in unemployment. People felt that they could “take their destiny into their own hands”. The situation changed at the end of 2008 due to the global financial crisis. At that time, a feeling of insecurity began to grow. This could potentially encourage the activation of collectivist values, especially those related to security (deprivation of the need for security results in an increase in the preference for values connected with security; the so-called “values-gaps” gain in importance, as they are an expression of unsatisfied needs, fears and inner conflicts). After several years of functioning in the European Union, the vision of Poland again became the subject of public debate. Is the country to be “fully” liberal and integrate itself in various aspects – including the cultural one – with the West? Or maybe more “solidarity-oriented”? According to Ziółkowski,92 a “solidarity” Poland is one in which the introduction of the rules of the free market economy is accompanied by the state’s care for social issues, where an egalitarian understanding of justice in the distribution of wealth, the cultivation of the most valuable traditions, the recognition of the interests of the community and the transfer of responsibility for the individual to the entire society prevail. The identification with such a model of the state coexists with a certain system of values.

Czerniawska103,116–121 shows in her longstanding research that a positive attitude to the idea of a welfare state, the role of the state in regulating income and employment, the role of religious institutions in public life and the culture of one’s nation is associated with a higher preference for collectivist values. There are also clear and consistent relationships between an individualistic orientation in the value system and liberal beliefs in the economic sphere, the acceptance of secularization and the pursuit of cultural openness to the West.

The obtained research results may also be the basis for more general considerations. They make us wonder whether the change in mentality towards individualism “dictated” by the political transformation has unequivocally positive consequences. Does it not lead to a distorted form of individualism – unscrupulous competition, egoism, closing in on oneself, feeling of emptiness, loneliness, disappearance of the spirit of cooperation and solidarity, loss of sensitivity to others and of social perspective, which is far from the ideal of autonomy, authenticity, self-fulfilment and inner improvement in Maslow’s and Inglehart’s terms?

Rapid systemic change can contribute to the emergence of individualism in a narcissistic form in which the welfare of the other is not taken into account.122 Rather, narcissistic individualism creates an “animal” capitalism, associated with the idea of accumulation of wealth and nothing else. There is then an excessive focus on the self and an unlimited promotion of freedom. Relationships between people change abruptly, compassion and altruism decline, as does mutual trust and a sense of security. The consequence of this fact is an extreme weakening of social bonds, as well as a sharp conflict between generations in the axiological dimension. This state of affairs may lead to the lack of models necessary for the socialisation process and anomie of values of moral or interpersonal nature. People’s behaviour becomes less and less regulated by values and more and more regulated by the mechanism of social influence. These concerns seem all the more justified the more we want a system that takes account of the principle of equality, not only in the political dimension, but also in economic and cultural terms.

Brewer and Chen123 note that in analysing social change “towards individualism”, it is important to consider how the concept of “group” is understood. This underlies the distinction between two forms of collectivism: relational and group. Relational collectivism refers to a definition of the group in which emphasis is placed on strong – often kinship-based and thus numerically limited – interpersonal relationships in which significant others (the “node” of strong interpersonal relationships) play a major role. The self is considered by the subject in terms of mutual relationships, while the achievements of other – but closely related – people are identified with one’s own. The markers of this form of collectivism are sensitivity to the needs of others, a tendency to listen to advice and a desire to maintain harmony in relationships with the immediate social environment. Behaviour is determined by a sense of responsibility arising from one’s role. The second form of collectivism – group collectivism – refers to the group understood as a depersonalised social category, with whose members the subject does not have to, and often – due to its size – is not able to interact. One can therefore speak of a sense of community based on group membership, with members sharing the symbols of the group and producing a cognitive representation of it. In this case a strong social identification and self-definition is manifested through group membership. The achievements of the group are perceived as one’s own and are based on collective interdependence. The group becomes a representative of the individual, who in turn is dependent on the group, shares its norms, feels obliged and obliged to it, and as a result – strives for its welfare. The roles assigned by the group regulate a smaller (than in relational collectivism) number of behaviours, which has the consequence of increasing the scope of individual freedom.

Brewer and Chen123 point out that societies are evolving towards individualism. This involves the integration of individualistic values into cultures based on relational collectivism. According to the authors, systemic transformations should include – in addition to the adaptation of individualistic values – the adaptation of group collectivism, because only then does the aspiration to place oneself and others in a broadly (and not as in the case of relational collectivism – in a narrowly) understood social environment become apparent. Concern for the shape of the mentality of society should therefore be directed not only at stimulating individualism – which is undoubtedly pro-development in character – but also at expanding the form of mentality that group collectivism is. One might believe that democratic principles of rights/opportunities equality, going beyond the narrowly understood social group, are located within the framework of group collectivism. Only the adoption of a universalism perspective channels the overall concern for the well-being of people, motivates the activation of social justice criteria and determines tolerance towards difference. Otherwise – as the societies of Central and Eastern Europe have had to confront this problem in recent decades – one can observe a rupture of interpersonal bonds, a weakening of loyalty, a disintegration of the community and the emergence of extremely individualistic behaviour, taking into account only the particular interests of individuals (hence narcissistic individualism). The inevitable consequence, at least temporarily, is the instability of social life.

Conclusions

The article “Between collectivism and individualism – analysis of changes in value systems of students in the period of 15 years” presents the axiological characteristics of the young generation of Poles. The research was conducted in the years 2003–2018 – four times at 5-year intervals – so that it became possible to determine the nature and dynamics of changes in the system of values. The aim of the research was to answer the question whether, along with the “solidification” of liberal democracy and free market economy (the year 1989 is considered the beginning of political changes in Poland), changes in the mentality of the young generation of Poles “towards individualism” take place. The relatively higher preference for individualistic values in subsequent studies (ie in subsequent generations of students) was adopted as the measure of these changes. The main hypothesis was formulated, according to which the later the research was carried out, the relatively lower preference indicators were obtained for collectivist values and the relatively higher ones for individualistic values. The specific hypotheses expressed the idea of the main hypothesis, but took into account the configurations of the groups being compared (time distance was a criterion). Contrary to expectations, there was no increase in rates of preference for individualistic values “from study to study”. The trajectories of changes in value systems turned out to be much more complex (and thus more difficult to describe). It is true that higher indices of individualistic value preferences were diagnosed in the last survey (2018), as compared to the first one (2003), but the most “individualistic” turned out to be the group surveyed as the second survey round, ie in 2008. Due to the fact that multiple measurements were made (attention was paid to successive generations of students), it became possible to capture trends in changes in value systems over a 15-year period.

In the analysis of systemic change in Central and Eastern Europe, the construct of “collectivism-individualism” has been attributed particular importance (individualism has been considered an important psychological premise, as it involves the rational responsibility of the individual for his or her own existence). This is not surprising if one considers the famous triad characterising Western societies: “liberal democracy – free market economy – individualism”. However, one should think that individualism in its “pure” form will not solve the problem of the mentality of Central and Eastern European societies. Changes in mentality in the individualistic direction are “desirable” at most from the point of view of economic transformations (and only while ignoring information about the “Asian miracle”). The relationship between individualism and democracy is already of a more controversial nature. Individualism promotes autonomy and freedom, but its extreme intensity may lead to the loss of the broader social perspective, without which the democratic slogans of brotherhood and equality (which were raised in the social philosophy of the Old Continent) lose their addressee, and thus do not make sense. The contradiction between self-centredness and the pursuit of a harmonious social life then becomes apparent. In the description of mature democracies it becomes necessary – as the above cited Brewer and Chen did – to differentiate forms of collectivism. This makes it possible to describe the changes in mentality of systemically transforming societies at a more complex level.

At the end of the article, methodological remarks are made. It should be noted that while analysing changes in the axiological sphere, the cyclicality of measurements is important, especially when significant social events take place or different ways of thinking compete with each other on what is meant by a “good” state (which is manifested in the ideology of competing political parties). The choice of values is related to the “social time” in which a person lives, to the culmination of events, episodes and significant persons. Due to the fact that recent years have been filled with interesting events in the public sphere, the authors plan to repeat their research in 2023.

Another important methodological issue is how to measure values: should one focus on individual values or should they be put into more general categories (types)? The first approach – adopted in this research – provides a lot of information, which makes it difficult to describe coherent relationships. However, such measurement does not blur the importance of single values. Among the values belonging to one type (a type is an effect of averaging the indicators of several values) there may be those whose preference increases (eg “family security”) or decreases (eg “national security”). The averaged indicator will not show this subtle difference. This was pointed out eg by Feldman115 when he considered what is the better predictor of attitudes: a single value or a type of value? A comparison of value systems in the same sample groups but using the tool allowing for determining types of values (the Schwartz Portrait Value Questionnaire (PVQ-R3) will be the subject of analysis in the next publication. Other (beyond the value system) measures of collectivism and individualism will also be included to go beyond the simple opposition “individualism – collectivism”.

Declaration by Authors of the Nature of Research – Ethical Issues

The study was non-interventional in nature and did not require permission from the Ethics Committee. The research does not fall within the field of clinical psychology. Neither is it of a clinical nature. The well-being of the research participants could not be compromised in any way. The ranking of values may have prompted participants to reflect ethically. In Polish conditions for this kind of survey research the opinion of Ethics Committee is not required. The survey was conducted in accordance with Polish standards. This type of research does not in any way threaten the well-being of the people involved. The respondents were informed in advance that the research concerns beliefs about themselves. The respondents gave verbal consent in the presence of witnesses. They could resign from participation at any time. The survey was conducted during a 0.5-hour meeting (groups of 20–25 people). The respondents ordered values included in the questionnaires by assigning them appropriate ranks. The survey was anonymous and the participation in it was voluntary. The survey was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The results of the study are stored at the Faculty of Engineering Management, Bialystok University of Technology. Data analyses are stored on a protected disk.

Acknowledgments

1. This research is supported by Bialystok University of Technology and financed from a subsidy provided by the Minister of Science and Higer Education; 2. The publication has recived funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 8195330)

Author Contributions

The mentality of Central and Eastern European societies has become an interesting subject of research due to the radical transformations of the political and economic system. This article is a part of this area of interest. In the four-stage research (5-year cycle) we tried to answer the question whether the strengthening of liberal democracy and free market economy in Poland is accompanied by changes in the mentality towards individualism. On a more general level of consideration, the following question can be formulated: whether the triad “liberal democracy – free market economy – individualism”, which characterizes Western societies, is becoming a more distinct attribute of the young generation of Poles with the passage of time (the research covered a period of 15 years). The study focused on value systems, which are considered to be the key determinant of mentality. Diagnosing the value systems several times was a time-consuming task (and therefore sporadically documented in scientific publications), but it allowed us to grasp the direction and scope of their changes. The study has practical significance: whether people will function effectively in a given political and economic system depends on their mentality, and especially on their value systems. As Le Bon124 aptly observed in the late 19th century, a political system is a costume stuffed with the “spirit of the people”. It must correspond with what the people are like, what they want and what they aspire to.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bilsky W, Schwartz SH. Values and personality. Eur J Pers. 1994;8:163–181. doi:10.1002/per.2410080303

2. Schwartz SH. Value priorities and behavior: applying a theory of integrated value systems. In: Seligman C, Olson JM, Zanna MP, editors. The Ontario Symposium: The Psychology of Values. Vol. 8. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1996:1–24.

3. Schwartz SH, Cieciuch J, Vecchione M, et al. Refining the theory of basic individual values. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;103(4):663–688. doi:10.1037/a0029393

4. Rohan MJ, Zanna MP. Value transmission in families. In: Seligman C, Olson JM, Zanna MP, editors. The Ontario Symposium: The Psychology of Values. Vol. 8. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1996:253–276.

5. Roccas S, Sagiv L, Schwartz SH, Knafo A. The big five personality factors and personal values. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28(6):789–801. doi:10.1177/0146167202289008

6. Cukur CS, de Guzman MRT, Carlo G. Religiosity, values, and horizontal and vertical individualism-collectivism: a study of Turkey, the United States, and the Philippines. J Soc Psychol. 2004;144(6):613–634. doi:10.3200/SOCP.144.6.613-634

7. Oishi S, Hahn J, Schimmack U, Radhakrishan P, Dzokoto V, Ahadi S. The measurement of values across cultures: a pairwise comparison approach. J Res Pers. 2005;39:299–305. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2004.08.001

8. Roccas S. Religion and value system. J Soc Issues. 2005;61(4):747–759. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00430.x

9. Audretsch D. The Entrepreneurial Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

10. Gong Y, Huang JC, Farh JL. Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: the mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Acad Manag J. 2009;52:765–778. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.43670890

11. Lönnqvist JE, Verkasalo M, Helkama K, et al. Self-esteem and values. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2009;39(1):40–51. doi:10.1002/ejsp.465

12. Pieterse AN, Van Knippenberg D, Schippers M, Stam D. Transformational and transactional leadership and innovative behavior: the moderating role of psychological empowerment. J Organ Behav. 2010;31:609–623. doi:10.1002/job.650

13. Vauclair CM, Fisher R. Do cultural values predict individuals’ moral attitudes? A cross-cultural multilevel approach. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2011;41:645–657. doi:10.1002/ejsp.794

14. Sułkowski Ł. Kulturowe Procesy w Zarządzaniu [Cultural Processes in Management]. Warszawa: Difin; 2012.

15. Maltseva K. Cognitive organization of cultural values: cross-cultural analysis of data from Sweden and the USA. J Cogn Cult. 2014;14:235–262. doi:10.1163/15685373-12342123

16. Uñan F, Fernández-Serrano J, Ronnero I. Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship: the mediating effect of culture. Rev Econ Mund. 2013;33:21–47.

17. Barni D, Vieno A, Roccato M. Living in a non-communist versus in a post-communist European country moderates the relation between conservative values and political orientation: a multilevel study. Eur J Pers. 2016;30:92–104. doi:10.1002/per.2043

18. Laskovaia A, Shirokova G, Morris MH. National culture, effectuation, and new venture performance: global evidence from student entrepreneurs. Small Bus Econ. 2017;49:687–709. doi:10.1007/s11187-017-9852-z

19. Wiatr JJ. Leadership and political change: 25 years of transformation in post-communist Europe. J Comp Polit. 2016;9(2):4–14.

20. Czerniawska M. Wartość “osiągnięcia” a postawy wobec ustroju ekonomicznego i kwestii socjalnych [The value of “achievement” and attitudes toward the economic system and social issues]. Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie. 2018;3(1):129–141.

21. Shahid MS, Imran Y, Shehryar H. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions: an institutional embeddedness perspective. J Small Bus Entrep. 2018;30(2):139–156. doi:10.1080/08276331.2017.1389053

22. Szydło J. Kulturowe Ramy Zarządzania [Cultural Management Framework]. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Sophia; 2018.

23. Szydło J, Widelska U. Leadership values – the perspective of potential managers from Poland and Ukraine (comparative analysis).

24. Baluku MM, Matagi L, Musanje K, Kikooma JF, Otto K. Entrepreneurial socialization and psychological capital: cross-cultural and multigroup analyses of impact of mentoring, optimism, and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep Educ Pedagog. 2019;2(1):5–42. doi:10.1177/2515127418818054

25. Farcane N, Deliu D, Bureană E. A corporate case study: the application of Rokeach’s value system to corporate social responsibility (CSR). Sustainability. 2021;11:6612. doi:10.3390/su11236612

26. Fløvik L, Knardahl S, Christensen JO. The effect of organizational changes on the psychosocial work environment: changes in psychological and social working conditions following organizational changes. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2845. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02845

27. Chugumbaev RR, Chugumbaeva NN. Problems of transformation management business models in organizations. Lect Notes Netw Syst. 2020;115:318–325.

28. van Dijke M. Power and leadership. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;33:6–11. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.012

29. Torelli C, Leslie LM, Kim S. Power and status across cultures. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;33:12–17. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.05.005

30. Szydło J, Grześ-Bukłaho J. Relations between national and organisational culture-case study. Sustainability. 2020;12(4):1522. doi:10.3390/su12041522

31. Czerniawska M, Szydło J. Do values relate to personality traits and if so, in what way? – analysis of relationships. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:511–527. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S299720

32. Fischer R, Schwartz S. Whence differences in value priorities? Individual, cultural, or artifactual sources. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2011;42:1127–1144. doi:10.1177/0022022110381429

33. Leung K, Au A, Huang X, Kurman J, Niit T, Niit KK. Social axioms and values: a cross-cultural examination. Eur J Pers. 2007;21(2):91–111. doi:10.1002/per.615

34. Tibbs H. Changing cultural values and the transition to sustainability. J Fut Stud. 2011;15(3):13–32.

35. Askun V, Cizel R, Cizel B. Complex relationship of countries’ innovation level with social capital, economic value perception and political culture: fsQCA. J Econ Adm Sci. 2021;16(2):317–340. doi:10.17153/oguiibf.895910

36. Miller SV. Economic threats or societal turmoil? Understanding preferences for authoritarian political systems. Political Behav. 2017;39(2):457–478. doi:10.1007/s11109-016-9363-7

37. Speranza S. Public values and social communication. In: Maturo A, Hošková-Mayerová Š, Soitu DT, Kacprzyk J, editors. Recent Trends in Social Systems: Quantitative Theories and Quantitative Models. Vol. 66; 2017:107–126. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40585-8_10

38. Maslova OV, Shlyakhta DA, Yanitskiy MS. Schwartz value clusters in modern university students. Behav Sci (Basel). 2020;10(3):66. doi:10.3390/bs10030066

39. Shkurko A. Mapping cultural values onto the brain: the fragmented landscape. Integr Psychol Behav Sci. 2020. doi:10.1007/s12124-020-09553-0

40. Kasler J, Zysberg L, Gal R. Culture, collectivism-individualism and college student plagiarism. Ethics Behav. 2020;1–10. doi:10.1080/10508422.2020.1812396

41. Nishanbayeva S, Kolumbayeva S, Satynskaya A, Zhiyenbayeva S, Seiitkazy P, Kalbergenova S. Some instructional problems in the formation of family and moral values of students. World J Educ Technol Curr Issues. 2021;13(3):529–545. doi:10.18844/wjet.v13i3.5961

42. Paliliunas D. Values: a core guiding principle for behavior-analytic intervention and research. In: Behavior Analysis in Practice; 2021:1–11.

43. Trubshaw D. Transcendent individualism as the realm of absolute values. J Unification Thought. 2021;1:93–105.

44. Гринева СВ. Ценностный конфликт поколений как основа трансформации российского менталитета [The values conflict of generations as the basis for the transformation of the Russian mentality]. Вестник Сев Кавк техн ун та Гуманитар науки. 2003;1:57–60.

45. Башкирова ЕИ. Трансформация ценностей российского общества [The transformation of values in Russian society]. Полис. 2000;6:51–65.

46. Бобрышев ВА. Управление Процессом Формирования Системы Ценностей Российского Полиэтнического Общества И Идеология Реформ [Managing the Process of Forming the System of Values of the Russian Multi-Ethnic Society and Reform Ideology]. Майкоп: Адыгейский гос; 2005.

47. Бубнова ОЮ. Проблема трансформации нравственных ценностей в современном российском обществе [The problem of the transformation of moral values in contemporary Russian society]. Соврем гуманитар акад; 2005.

48. Котлярова ВВ. Динамика ценностей молодежи России в постсоветский период [The Dynamics of Values of Russian Youth in the Post-Soviet period]. Ростов н/Д: Рост гос; 2005.

49. Журавлева НА. Динамика ценностных ориентаций молодёжи в условиях социально-экономических изменений [Dynamics of value orientations of young people under conditions of socio-economic changes]. Психологич журнал. 2006;27(1):35.

50. Czerniawska M, Чернявска М. Ценности и социально-политические установки глазами российского и польского студенчества [Values and Socio-political Attitudes in the Eyes of Russian and Polish Students]. СПб: Изд-во СПбГУЭФ; 2007.

51. Czerniawska M, Чернявска М. Динамика ментальности в трансформирующихся обществах [The dynamics of mentality in transforming societies]. Известия Российского Государственного Университета имени А.И. Герцена. 2007;9(47):133–148.

52. Carr SC, McWha I, Maclachlan M, Furnham A. International-local remuneration differences across six countries: do they undermine poverty reduction work? Int J Psychol. 2010;45(5):321–340. doi:10.1080/00207594.2010.491990

53. Selezneva AV. Psychological analysis of political values in contemporary Russian public: generational aspect. Tomsk State Univ J Philos Sociol Political Sci. 2011;15(3):22.

54. Leska D. The main phases of the formation of system of political parties in Slovakia after 1989. Sociologia. 2013;45(1):71–88.

55. Magun V, Rudnev M, Schmidt P. A Typology of European values and Russians’ basic human values. Russian Soc Sci Rev. 2017;58(6):509–540. doi:10.1080/10611428.2017.1398547

56. Staehr K. The choice of reforms and economic system in the Baltic states. Comp Econ Stud. 2017;59(4):498–519. doi:10.1057/s41294-017-0037-1

57. Sokola-Nazarenko M, Martinsone K, Mihailova S, Levina J, Elina K. The dynamics of value system in 1998 and 2015: longitudinal research in Latvia. SHS Web Conf. 2018;52(1). doi:10.1051/shsconf/20185101008

58. Bardi A, Schwartz SH. Values and behavior: strength and structure of relations. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(10):1207–1220. doi:10.1177/0146167203254602

59. Schwartz SH, Bardi A. Influences of adaptation to communist rule on value priorities in Eastern Europe. Polit Psychol. 1997;18:385–410. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00062

60. Bokszański Z. Indywidualizm a Zmiana Społeczna [Individualism and Social Change]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN; 2007.

61. Cieciuch J. Kształtowanie Systemu Wartości od Dzieciństwa do Wczesnej Dorosłości [Shaping the Value System from Childhood to Early Adulthood]. Warszawa: Liberi Libri; 2013.

62. Vecchione M, Schwartz S, Davidov E, Cieciuch J, Alessandri G, Marsicano G. Stability and change of basic personal values in early adolescence: a 2-year longitudinal study. J Pers. 2019. doi:10.1111/jopy.12502

63. Sułek A. Wartości dwóch pokoleń [The values of two generations]. In: Nowak S, editor. Ciągłość i Zmiana Tradycji Kulturowej [Continuity and Change in Cultural Traditions]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN; 1989:293–338.

64. Misztal M. Elementy Systemu Wartości Współczesnego Społeczeństwa Polskiego [Elements of Contemporary Value System Polish Society]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN; 1990.

65. Promieńska H. Trwanie i Zmiana Wartości Moralnych [Persistence and Change of Moral Values]. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego; 1991.

66. Skarżyńska K. Konformizm i Samokierowanie jako Wartości [Conformism and Self-Direction as Values]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Psychologii PAN; 1991.

67. Skarżyńska K. Młodzież ’90: wartości i możliwości młodego pokolenia [Youth '90: values and opportunities of the young generation]. In: Łukaszewski W, editor. W Kręgu Teorii Czynności [In the Circle of Theory Activities]. Kolokwia Psychologiczne (T. 5). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Psychologii PAN; 1995:9–21.

68. Skarżyńska K. Czy jesteśmy prorozwojowi? Wartości i przekonania ludzi a dobrobyt i demokratyzacja kraju [Are we pro-development? Values People's values and beliefs and prosperity and democratization of the country]. In: Drogosz M, editor. Jak Polacy Przegrywają. Jak Polacy Wygrywają [How Poles Lose. How Poles Win]. Gdańsk: GWP; 2005:69–92.

69. Iwanicka K, Karwińska A. Wartości i postawy jako czynniki zmian społecznych [Values and attitudes as factors of social change]. In: Dyoniziak R, Iwanicka K, Karwińska A, Nikołajew J, Pucek Z, editors. Społeczeństwo w Procesie Zmian. Zarys Socjologii Ogólnej [Society in the Process of Change. Outline of General Sociology]. Kraków: Copyright by Ryszard Dyoniziak and Towarzystwo Autorów Prac Naukowych Universitas; 1992.

70. Pawełczyńska A. Wartości i ich Przemiany [Values and their Transformation]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN; 1992.

71. Sztumski J. Społeczeństwo a Wartości [Society and Values]. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego; 1992.

72. Jusiak R, Wawro WF. Przemiany preferencji wartości młodzieży polskiej okresu “przełomu” [Changes in the value preferences of young people of Polish youth in the “breakthrough” period]. Etnos. 1993;23:21–29.

73. Dyczewski L. System wartości w świadomości młodzieży [Value system in the consciousness of youth]. In: Ożóg T, editor. Nauki Społeczne o Młodzieży [Social Science of Youth]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL; 1994:47–72.

74. Dyczewski L. Kultura Polska w Okresie Przemian [Polish Culture in Transition]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL; 1995.

75. Dyczewski L. Wartości dorastającego pokolenia Polaków w okresie transformacji systemowej [Values of the growing up generation of Poles in the period of systemic transformation]. In: Sołtysiak T, Łabuć-Kryska I, editors. Trudne Problemy Dorastającego Pokolenia [Difficult Problems of the Adolescent Generation]. Bydgoszcz: Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna; 1998:35–54.

76. Mach B. Międzypokoleniowy przekaz wartości w warunkach zmiany systemowej [Intergenerational transmission of values in the conditions systemic change]. Kult Spolecz. 1994;4:29–39.

77. Sopuch R. Postawy Studentów wobec Życia i Wybór Wartości [Students' Attitudes toward Life and Value Choices]. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo UG; 1994.

78. Anasz W. Wartości Młodego Pokolenia w Dobie Transformacji Ustrojowej Polski [Values of the Young Generation in the Time of the Poland's Systemic Transformation]. Częstochowa: Wydawnictwo WSP; 1995.

79. Doniec R. Wartości osobowe w systemie wartości rodziny miejskiej w układzie międzypokoleniowym [Personal values in the value system of an urban family in an intergenerational arangement]. In: Adamski F, editor. Wartości – Społeczeństwo – Wychowanie [Values - Society - Education]. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Vol. 21. 1995:76–92.

80. Doniec R. Rodzina Wielkiego Miasta: Przemiany Społeczno-Moralne w Świadomości Trzech Pokoleń [The Family in the Big City: Social and Moral Transformations in the Consciousness of Three Generations]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego; 2001.

81. Frąckowiak T, Modrzewski J, editors. Socjalizacja i Wartości (Aktualne Konteksty) [Socialization and Values (Current Contexts)]. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Eruditus; 1995.

82. Mariański J. Młodzież między Tradycją a Ponowoczesnością: Wartości Moralne w Świadomości Maturzystów [Youth between Tradition and Postmodernity: Moral Values in the Consciousness of High School Graduates]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Naukowe KUL; 1995.

83. Mariański J. Młodzież maturalna i wartości podstawowe [High school graduates and core values]. Studia Plockie. 1996;24:215–237.

84. Mariański J. Kryzys Moralny czy Transformacja Wartości? Studium Socjologiczne [Moral Crisis or Values Transformation? A Study Sociological]. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL; 2001.

85. Mariański J. Podstawowe orientacje moralne w społeczeństwie polskim [Basic moral orientations in Polish society]. In: Gołębiowski B, editor. Moralność Polaków. Etos i Etnos. Dylematy Współczesne [Morality of Poles. Ethos and Ethnos. Contemporary Dilemmas]. Łomża: Oficyna Wydawnicza Stopka; 2001.

86. Mariański J. Religia i moralność w społeczeństwie polskim – ciągłość i zmiana [Religion and morality in Polish society - continuity and change]. In: Mariański J, Smyczek L, editors. Wartości, Postawy i Więzi Moralne w Zmieniającym się Społeczeństwie [Values, Attitudes and Moral Ties in a Changing Society]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM; 2008.

87. Krasnodębska A. Orientacje Aksjologiczne Młodzieży Akademickiej: Z Badań nad Studentami Uczelni Opolskich [Axiological Orientations of Youth Academic Youth: From Research on Students of Opole Universities]. Opole: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Opolskiego; 1997.

88. Szymański MJ. Młodzież wobec Wartości [Youth in the Face of Values]. Warszawa: Instytut Badań Edukacyjnych; 1998.

89. Świda-Ziemba H. Wartości Egzystencjonalne Młodzieży Lat Dziewięćdziesiątych [Existential Values of Youth of the Nineties]. Warszawa: Copyright by H. Świda-Ziemba i ISNS UW; 1998.

90. Sufin Z. Ewolucja wartości materialnych i pozamaterialnych [The evolution of material and non-material values]. In: Beskid L, editor. Zmiany w Życiu Polaków w Gospodarce Rynkowej [Changes in People's Lives in the Economy Market]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar; 1999.

91. Ziółkowski M. Przemiany Interesów i Wartości Społeczeństwa Polskiego [Changes of Interests and Values of the Polish Society]. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Fundacji Humanitora; 2000.

92. Ziółkowski M. Zmiany systemu wartości [Changes in the value system]. In: Wasilewski J, editor. Współczesne Społeczeństwo Polskie. Dynamika Zmian [Contemporary Polish Society. The Dynamics of Change]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar; 2006:145–174.

93. Sawczuk W. Wartości Preferowane przez Studentów w Okresie Transformacji Ustrojowej [Values Preferred by Students in the Period of Political Transformation]. Olsztyn: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurskiego; 2000.

94. Gilejko LK. W poszukiwaniu nowych wartości [In search of new values]. In: Gołębiowski B, editor. Moralność Polaków. Etos i Etnos. Dylematy Współczesne [Morality of Poles. Ethos and Ethnos. Contemporary Dilemmas]. Łomża: Oficyna Wydawnicza Stopka; 2001.

95. Błasiak A. Młodzież – Świat Wartości [Youth - A World of Values]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM; 2002.

96. Smyczek L. Dynamika Przemian Wartości Moralnych w Świadomości Młodzieży Licealnej: Studium Panelowe [The Dynamics of Moral Value Transitions in the Consciousness of High School Youth: A Panel Study]. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL; 2002.

97. Miluska J. Indywidualizm i kolektywizm polskich studentów w okresie transformacji systemowej [Individualism and collectivism of Polish students during systemic transformation]. In: Jakubowska U, Skarżyńska K, editors. Demokracja w Polsce – Doświadczenie Zmian [Democracy in Poland - Experience Changes]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo SWPS Academica; 2005.

98. Bielska E. Studenci a Liberalny System Wartości w Polsce i Danii [Students and the Liberal Value System in Poland and Denmark]. Gdańśk: GWP; 2006.

99. Czapiński J, editor. Diagnoza Społeczna 2007 [Social Diagnosis 2007]; November 20, 2020. Available from: http://www.diagnoza.com.

100. Budzyńska E. Podzielane czy dzielące? Wartości społeczeństwa polskiego [Shared or divided? Values of the Polish society]. In: Mariański J, Smyczek L, editors. Wartości, Postawy i Więzi Moralne w Zmieniającym się Społeczeństwie [Values, Attitudes and Moral Ties in a Changing Society]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM; 2008.

101. Czerniawska M, Szydło J. More or less pro-liberal? Comparative analysis of the attitudes of young people entering the labour market. Eur Res Stud J. 2020;XXIII(3):564–580. doi:10.35808/ersj/1655

102. Czerniawska M, Szydło J. The worldview and values – analysing relations. WSEAS Trans Bus Econ. 2020;17(58):594–607. doi:10.37394/23207.2020.17.58

103. Czerniawska M. Zmiany Wartości i Postaw Młodzieży w Okresie Przeobrażeń Ustrojowych. Indywidualizm versus Kolektywizm [Changes in Values and Attitudes of Youth in the Period of Political Transformations. Individualism versus Collectivism]. Białystok: Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Białostockiej; 2010.

104. Czerniawska M. O wartościach i ich zmianie – raport z badań porównawczych nad systemami wartości studentów [About values and their change –a report from researchcomparative research on students' value systems]. Kult Eduk. 2016;113(3):135–153. doi:10.15804/kie.2016.03.08

105. Rokeach M. The Nature of Human Values. New York: Free Press; 1973.

106. Ross L, Nisbett RE. Человек и Ситуация [Man and the Situation]. Мoscow: Аспект Пресс; 2000.

107. Sadowski A. Społeczne Problemy Miejscowości Północno-Wschodniej Polski w Procesie Transformacji [Social Problems of North-Eastern Polish Localities in the Process of Transformation]. Białystok: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku; 2001.

108. Schwartz SH, Bilsky W. Toward a psychological structure of human values. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:550–562. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.550

109. Schwartz SH. Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1992;25:1–65. doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60281-6

110. Schwartz SH. Universalism values and the inclusiveness of our moral universe. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2007;38:711–728. doi:10.1177/0022022107308992

111. Brzozowski P. Skala Wartości (SW). Polska Adaptacja Value Survey M. Rokeacha [Value Scale (SW). Polish Adaptation of the Value Survey M. Rokeach]. Warszawa: Wydział Psychologii Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego; 1989.

112. Brzozowski P. Wzorcowa Hierarchia Wartości [-Exemplary Hierarchy of Values]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS; 2007.

113. Rokeach M. Two-value model of political ideology and British politics. In: Rokeach M, editor. Understanding Human Values. New York: Free Press; 1979.

114. Rohan MJ. A rose by any name? The values construct. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2000;4:255–277. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0403_4

115. Feldman S. Values, ideology, and the structure of political attitudes. In: Sears DO, Huddy L, Jervis R, editors. Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology. New York: Oxford; 2003.

116. Czerniawska M. “Wolność” i “równość”, … a może “zbawienie”? – wartości determinujące postawy wobec ustroju ekonomicznego i kwestii socjalnych [“Freedom” and “equality”, ... or perhaps “salvation”? - Values determining attitudes towards the economic system and social issues]. Prakseologia. 2018;160:19–40.

117. Czerniawska M. Czy wartość “wolność” determinuje postawy wobec wolności politycznej i osobistej? [Does the value of “freedom” determine attitudes towards political and personal freedom?]. Pedagog Spolecz. 2012;3(45):89–104.

118. Czerniawska M. Stosunek do kultury i tradycji narodowej oraz jego aksjologiczne uwarunkowania [Attitude towards culture and national tradition and its axiological determinants]. Ekon Zarz. 2013;5(2):23–37.

119. Czerniawska M. Czy intelektualiści lubią kapitalizm? Rola wartości poznawczych w determinowaniu postaw wobec ustroju ekonomicznego i zabezpieczeń socjalnych [Do intellectuals like capitalism? The role of cognitive valuescognitive values in determining attitudes towards the economic system and social security]. Ekon Zarz. 2014;6(1):252–262.

120. Czerniawska M. Aksjologiczne uwarunkowania postaw studentów wobec równości praw i równości podziału [Axiological determinants of students' attitudes -towards equality of rights and equality of distribution]. Ekon Zarz. 2015;7(1):232–253.

121. Czerniawska M. Empatia a postawy wobec ustroju ekonomicznego i kwestii socjalnych [Empathy and attitudes toward the economic system and social issues]. Terazniejszosc Czlowiek Edukacja. 2015;2(70):109–117.

122. Triandis HC, McCusker C, Hui CH. Multimethod probes of individualism and collectivism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59(5):1006–1020. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1006

123. Brewer MB, Chen YR. Where (Who) are collectives in collectivism? Toward conceptual clarification of individualism and collectivism. Psychol Rev. 2007;114(1):133–151. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.133

124. Le Bon G. Psychologia Socjalizmu (Psychologie Du Socialisme) [The Psychology of Socialism]. Warszawa: Nepo; 1997.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.