Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 15

Beliefs and Attitudes of Health Care Professionals Toward Mental Health Services Users’ Rights: A Cross-Sectional Study from the United Arab Emirates

Authors Abdulla A, Webb HC , Mahmmod Y, Dalky HF

Received 18 June 2022

Accepted for publication 1 September 2022

Published 28 September 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 2177—2188

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S379041

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Ayesha Abdulla,1 Heather C Webb,2 Yasser Mahmmod,3 Heyam F Dalky4

1Vice President of Academic Affairs, Higher Colleges of Technology, Dubai, United Arab Emirates; 2Faculty of Business, Higher Colleges of Technology, Dubai, United Arab Emirates; 3Faculty of Health Sciences, Higher Colleges of Technology, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates; 4RN Faculty of Nursing Jordan University of Science & Technology, Irbid, Jordan

Correspondence: Heather C Webb, Higher Colleges of Technology, PO Box 15825, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Tel +971563688746, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The beliefs and attitudes of healthcare professionals (HCPs) towards service user’s rights in mental healthcare are critical to understanding as it impacts the quality of care and treatment, leading to social discrimination and possible coercive professional practices. This study aimed to investigate the association between the HCPs’ beliefs and attitudes towards service users’ rights in seeking treatment in the UAE and to identify or may predict the stigmatized attitudes and behaviors among HCPs.

Patients and Methods: Data was collected from HCPs participants working at three healthcare entities (n=307) allocated at selected primary and tertiary healthcare settings that specifically treat mental disorders. The Health Professionals Beliefs and Attitudes towards Mental Health Users’ Rights Scale (BAMHS) questionnaire was used to assess the beliefs and attitudes. Unconditional associations using regression models included whether HCPs provide care to specific mental health patients, whether treating mental health patients is part of their jobs, whether HCPs receive professional training for mental healthcare, nationality of HCPs, and the number of years of professional experience.

Results: Our findings demonstrate that HPCs understand mental disorders and feel that individuals’ rights should be equal to those who do not have mental disorders while believing in autonomy and freedom, but there is a level of discrimination and a high level of social distance. HCPs are less tolerant when interacting with those with mental disorders outside their professional lives.

Conclusion: Interventions with long-term follow-up activities must be implemented and assessed using assessment systems that measure acquired knowledge and actual behavioral change to ensure anti-stigma impact in practice and policy.

Keywords: attitudes, HCPs, mental disorder, BAMHS, the United Arab Emirates, service users’ rights

Introduction

The beliefs and attitudes of healthcare professionals (HCPs) towards service users’ rights in mental healthcare are critical to understanding as it impacts the quality of care and treatment, leading to social discrimination and possible coercive professional practices.1–7 Nonetheless, people with diagnosed mental disorders have faced discrimination from HCPs.8 When applied to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) context, these beliefs and attitudes are similar to HCPs in other countries.

The UAE government has recently recognized the necessity of integrating people with serious mental disorders into social service organizations and has established community development agencies in several of the country’s major cities.9 Based on the number of psychiatric beds accessible for the general population, as well as 0.3 psychiatrists, 0.51 psychologists, and 0.25 social workers available per 100,000, the UAE’s investment in mental healthcare is relatively low, similar to that of other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.10,11 As a result, the UAE has made it a priority to increase investment in mental health services as well as human capacity building. However, mental health services in the UAE are still scattered, even though, as of 2018, mental health treatment is covered by mandatory health insurance, albeit only in outpatient settings.12,13 As a result, there is a minimal collaboration between mental health and primary care providers.

The expatriate population in the UAE consists of people of Arab, Asian (eg Indian, Pakistani, and Filipino), and Western origin.14 In the UAE, the indigenous population is a minority, and foreign HCPs provide the majority of the medical treatment. There is a natural tendency for social discrimination to rise as more culturally different people coexist in the UAE, which has an impact on mental health services and can contribute to attitudes towards service users.15 In order to alter beliefs and attitudes, it is essential to comprehend the effects of dealing with service users who have mental disorders. Individual attitudes are influenced by empathy levels, personality factors, and structural and systemic influences in treatment.16–18 Service users should be empowered to participate in their treatment and care as they have rights.19,20 Attitudes of HCPs towards service users have been well documented, but no comparative research has been conducted in the UAE.21,22 Our research objective is to investigate the association between the HCPs’ beliefs and attitudes towards service users’ rights in seeking treatment in the UAE In addition, we are aiming to identify factors that may be associated with beliefs and attitudes in the UAE.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Since there is no baseline numerical data on attitudes from HCPs towards service users in the UAE, an exploratory cross-sectional design was selected. There were two sections: sociodemographic and the Health Professionals Beliefs and Attitudes towards Mental Health Users’ Rights Scale (BAMHS) scale. The sociodemographic information included: nationalities (Table 1), professional group (Table 2), education level (Table 3), primary work settings (Table 4), types of mental health services (Table 5), and the expected proportion of people in the UAE who suffer from a mental health disorder (Table 6). The BAMHS scale was developed specifically to look at service users’ rights and has a high level of correlation with our investigative associations between HCPs’ attitudes, while validated in settings such as inpatient, outpatient and rehabilitation facilities.21,22 The BAMHS scales’ four dimensions had previously shown a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.6–0.8 which indicates a level of reliability. A confirmatory factor analysis was also used to create a congruent four-dimensional model. These dimensions—system critique, freedom, empowerment, and discrimination—are more suited to the context of the UAE, where mental health care is still in its infancy and there are various kinds of mental health specialists. No scale is available that covers professions working in various settings.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of the Study Population in the Healthcare Study with Respect to Nationality |

|

Table 2 Results of the Responses to “Which Professional Group Do You Belong to?” |

|

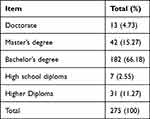

Table 3 Descriptive Statistics of the Study Population in the Healthcare Study in Respect to the Highest Education Level |

|

Table 4 Results of the Responses to “What are the Primary Work Settings Where You Work for About Five Hours or More per Week?” |

|

Table 5 Results of the Responses About the Types of Mental Health Services That the Participants Personally Provide to Patients as Part of Their Regular Professional Activities |

|

Table 6 The Responses to the Question on the Expected Proportion of People in the UAE Who Might Suffer from a Mental Health Disorder During Their Life |

The survey was sent out in both English and Arabic. The survey was originally written in English and translated by a professional Arabic speaker before being sent out. Once the results came back, the Arabic was translated back to English and combined with the English survey.

Recruitment and Participants

Participants were recruited from the largest government healthcare facilities in Abu Dhabi and Dubai as these facilities are the best representative of healthcare facilities in the UAE from the aspect of size and number of treated patients. This information was obtained from the healthcare officials and personal communications. Participants were selected based on a conveniently non-sampling method. The total number of responses, 307, refers to the total participants who received the survey and agreed to participate. As shown in the descriptive statistics, they represented a wide range of specialties, nationalities, and education levels.

Inclusion criteria and settings included a governmental teaching hospital, a social development care organization, and ambulance care, which were chosen for their care in various demographic segments. The government hospital received most of the responses, even though response rates were inconsistent among the three healthcare settings. Exclusion criteria were governmental healthcare facilities not situated in the two designated Emirates and private healthcare facilities.

Data Collection

Between November 2020 and February 2021, research activities and data were collected. The survey took about 10–15 minutes to complete on average. The questionnaire was written in both English and Arabic.

Measures

It consists of 25 items using a 4-point Likert value. The dimensions consist of: system criticism/justifying beliefs (item number BAMHS2, BAMHS6, BAMHS9, BAMHS10, BAMHS11, BAMHS12, BAMHS23, BAMHS25), freedom/coercion (item number BAMHS3, BAMHS4, BAMHS13, BAMHS20, BAMHS21), empowerment/paternalism (BAMHS1, BAMHS5, BAMHS7, BAMHS16, BAMHS17, BAMHS19, BAMHS22, BAMHS24), tolerance/discrimination (item number BAMHS8, BAMHS14, BAMHS15, BAMHS18).

Data Analysis

Before performing any statistical analysis, data were checked for missing values. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the sample. Data on BAMHS scale items were combined totally disagree/disagree and totally agree/agree, which ended up with two levels (Agree, and Disagree) and were regarded as the explanatory variables in our statistical models. The outcome variables of interest included the following: whether HCPs provide care to specifically mental health patients (yes Vs no), whether treating mental health patients is part of their jobs (yes Vs no), and whether HCPs receive professional training for mental healthcare (yes Vs no), nationality of HCPs (Emirati Vs Expat), and the number of years of professional experience. Logistic regression models were employed for categorical outcome variables, while linear regression model was used for only one outcome variable based on the description and distribution of the variable (number of years of professional experience). The p-value and odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were recorded for each variable. In all statistical analyses, the results were considered to be significant, with a p-value <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.3.3.23

Ethical Considerations

The aims and data collection procedures were approved by the Research Committee of Higher Colleges of Technology, Dubai, UAE, as part of an interdisciplinary research grant (Fund No. 113120). The participants autonomously decided to participate voluntarily. Informed consent was presented where participants had to check off for acknowledgment before filling in the survey. The research purposes were explained. Since the survey was sent electronically over email as a SurveyMonkey link, participants’ responses’ privacy and confidentiality were protected. Additionally, nobody outside the research team was informed of the participant’s involvement.

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

Data was analyzed from 275 observations with complete answers, while 32 were excluded for missing values. Those 32 individuals (21 female and 11 male) with missing values were omitted in the initial screening of the data and before running the analytic statistical analysis. They did not complete the entire survey and did not respond to the 25 statements of BAMHS. The characteristics those individuals briefly include a wide range of age (33 to 55 years), 25 were expat and 7 were UAE national, years of experience were ranged from 1 to 32 years and level of education was ranged from diploma to doctorate. For the Arabic version, 56 (90.3%) participants completed the survey, and 6 (9.7%) did not. For the English version, 219 (89.7%) participants completed it, while 25(10.3%) did not. Participants comprised 159 females (57.8%) and 116 males (42.2%). The number of years of practice was ranged from 1 to 45 years (mean = 15.25 and median = 14). The age of participants was ranged from 25 to 61 years old (mean= 39.56 and median= 38). In total, 191 participants were working in Abu Dhabi and 84 were from Dubai. About 249 of the participants were seeing the patients on a regular basis, while 26 were not. The number of years of professional experience of the study participants were ranged from 0 to 40 years (mean= 14.26 and median= 14). Finally, the results of the BAMHS scale are presented in Supplementary Table 1X.

Descriptive Statistics: System Criticism and Justifying Beliefs

In the subscale system criticism and justifying beliefs (items BAMHS2, BAMHS6, BAMHS9, BAMHS10, BAMHS11, BAMHS12, BAMHS23, BAMHS25), over 65.1% disagreed that it was possible to recover from a mental illness without professional interventions. At the same time, 80.4% agree that mental disorders are diseases like any other. In comparison, 65.7% agree that it is due to their mental disorder when patients behave aggressively. However, 57.7% agree that declaring someone with a severe mental disorder incapacitated is a good way of taking care of that person. Additionally, 77.7% agree that individuals with a mental disorder have the same rights as others. Ultimately, 88% agree that coercive measures are applied only when necessary. However, it was almost even when it came to whether some patients will never be able to recover in that 50.9% disagree and 49.1% agree. For the most part, overwhelmingly, 94.9% agree that mental health professionals work collaboratively with patients.

Descriptive Statistics: Freedom and Coercion

In the subscale freedom and coercion (items BAMHS3, BAMHS4, BAMHS13, BAMHS20, BAMHS21), 70.2% agree that people should not be involuntarily hospitalized if they do not pose a threat to the integrity of others, while 84.4% agree that sometimes it is necessary to restrain patients mechanically. When a patient behaves aggressively due to situations that occur, for example, in involuntary admissions, 78.7% agree. In comparison, 80.2% agree that greater importance should be placed on promoting the patient’s independence than reducing the patient’s symptoms. However, if there are not enough staff, then 56.8% agree that mechanical restraints are the only way to manage violent situations.

Descriptive Statistics: Empowerment and Paternalism

In the subscale empowerment and paternalism (items BAMHS1, BAMHS5, BAMHS7, BAMHS16, BAMHS17, BAMHS19, BAMHS22, BAMHS24), 75.6% agree that the possibility of people with severe mental disorders having children should be regulated. Overwhelmingly, 93.1% agree that patients with severe mental disorders require clearer instructions than other patients. Whether professionals should have more say than patients in making treatment decisions, findings show that 71.9% agree. At the same time, 86.8% agree that people with severe mental disorders always require support to live independently. Additionally, 81.3% agree that objective tests should be prioritized over the professionals’ and patients’ opinions. Respecting the patients’ dignity is important, but some aspects of treatment may require flexibility; 90.8% agree. Interestingly, 83.2% agree that it is important not to get emotionally involved when dealing with patients. Finally, 64.1% try to leave their personal values aside in their clinical practice.

Descriptive Statistics: Tolerance and Discrimination

In the subscale tolerance and discrimination (items BAMHS8, BAMHS14, BAMHS15, BAMHS18), 51.1% that individuals incapacitated by severe mental health problems should have the right to vote. Regarding being comfortable making friends with someone with a severe mental disorder, 52% agreed. In contrast, 35.3% agree to being uncomfortable with patients who regularly use emergency services. Only 36.6% agree to be comfortable if a person with a mental disorder were a teacher.

Unconditional Associations

The unconditional association of providing healthcare to mental health patients is provided in Table 7. When compared with individuals who are not providing healthcare to people with mental disorders, individuals providing healthcare to people with mental disorders were more likely (OR: 1.76, 95% CI: 0.99–3.25) to disagree with the item ” People should not be involuntarily hospitalized if they do not pose a threat to the integrity of others”. When compared with individuals who are not providing healthcare to people with mental disorders, individuals providing healthcare to people with mental disorders were more likely (OR: 1.88, 95% CI: 1.11–3.1) to disagree with the item ”I am uncomfortable with patients who regularly use emergency services”. When compared with individuals who are not providing healthcare to people with mental disorders, individuals providing healthcare to people with mental disorders were more likely (OR: 1.79, 95% CI: 0.91–3.73) to disagree with the item ”Greater importance should be placed on promoting the patient’s independence than on reducing the patient’s symptoms”. The other tested BAMHS scale items were not significant.

|

Table 7 Results of Unconditional Association of Providing Healthcare to Mental Health Patients (Yes or No) and Other Variables of Interest Using the Univariable Logistic Regression Model |

As for the regular observation of mental health patients, when compared with HCPs, individuals who did not see mental health patients on a regular basis as part of their regular professional job, individuals who see mental health patients on regularly were less likely (OR: 0.285, 95% CI: 0.082–0.774) to disagree with the item “ I would be comfortable if a person with a mental disorder were a teacher in a school”. The other tested BAMHS scale items were not significant.

As for the professional training, when compared with HCPs individuals who did not receive professional training, individuals who received professional training were more likely (OR: 2.78, 95% CI: 1.29–6.49) to disagree with the item “People with severe mental disorders always require support to be able to live independently”. The other tested BAMHS scale items were not significant.

The association of whether HCPs are local (Emirati) or expatriate (Expat) using a univariable logistic regression model is shown in Table 8. When compared with the Emirati participants, Expat participants were less likely (OR: 0.295, 95% CI: 0.07–0.88) to disagree with the item “People should not be involuntarily hospitalized if they do not pose a threat to the integrity of others”. When compared with the Emirati participants, Expat participants were less likely (OR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.17–0.89) to disagree with the item “I am uncomfortable with patients who regularly use emergency services”. When compared with the Emirati participants, Expat participants were more likely (OR: 4.95, 95% CI: 1.74–13.09) to disagree with the item ”Respecting the patients’ dignity is important, but some aspects of treatment may require flexibility”. When compared with the Emirati participants, Expat participants were less likely (OR: 0.34, 95% CI: 0.13–0.81) to disagree with the item “Some patients will never be able to recover”. The other tested BAMHS scale items were not significant.

|

Table 8 Results of Unconditional Association of the Nationality (Emirati vs Expat) of the Healthcare Providers and Other Variables of Interest Using the Univariable Logistic Regression Model |

The unconditional association between the number of years of professional experience and BAMHS scale items using the linear regression model is shown in Table 9. Participants having more years of professional experience are more likely to positively and significantly disagree with the statements of BAMHS2, BAMHS18, BAMHS22, and BAMHS23 compared to those with fewer years of experience. Meanwhile, they are more likely to negatively and significantly disagree with the statement of BAMHS10. The other tested BAMHS scale items were not significant.

|

Table 9 Results of Association Between the Number of Years of Professional Experience of the Healthcare Providers and Other Variables of Interest Using the Linear Regression Model |

Discussion

Our research objective was to investigate the association between the HCPs’ beliefs and, attitudes towards service users’ rights of mental health treatment in the UAE. We used the BAMHS measures because it is crucial to raise awareness among mental health HCPs so that non-stigmatizing and empowering attitudes can be promoted given the severity of the effects of beliefs and attitudes on people receiving mental health care. The four subscales’ results showed low levels of support for users’ “empowerment” and high levels of “discrimination” towards those who have mental disorders. HCPs are essential in bringing about change since their perspectives on mental disorders have an effect on others.24 Furthermore, HPCs feel they/themselves have total control over therapy and care because they are the experts, which is another empowerment aspect. In addition, they exhibit less tolerance when engaging with those who suffer from mental disorders while they are not at work.

System Criticism and Justifying Beliefs

The study’s findings demonstrate that, for the most part, HPCs understand mental disorders and feel that individuals’ rights should be equal to those who do not have mental disorders. Working in tandem with service users is overwhelmingly believed to be the best course of action for treatment, yet only half of the participants feel that individuals will be able to recover. HCPs are essential in the treatment and rehabilitation of people with mental disorders. According to the findings, nearly half thought that certain people would never be able to recover. As per a cross-sectional survey of 27 countries, mental healthcare services are the leading source of stigma and discrimination, with 38% reported feeling explicitly disrespected by mental health personnel when seeking mental health care.25 The effects of attitudes on treatment results are amplified.26 In contrast, a Lebanese study found that HPCs had strong stigmatized beliefs against those who suffer from mental disorders.27

Freedom and Coercion

It has been shown that collaborative care enhances mental health management in hospital settings, especially among surgeons who have a more favorable attitude toward mental disorders.28 Our findings show that while 80% of respondents feel that service users should be free to choose their own treatment, over 84% of participants believe that artificial restrictions are occasionally necessary and should be removed. Although this shows a positive attitude, HCPs could be skeptical about treatment strategies.

Empowerment and Paternalism

A paternalistic healthcare system will be necessary if authoritarianism is high, despite the fact that awareness of mental disorders lessens behavioral stigmatization.29 Contrarily, prejudices persist since HCPs continue to hold beliefs about mental disorders that are shaped by their personal experiences.30,31 Surprisingly, 75% of respondents said that service users with serious mental disorders who have children should be subject to regulation, which would violate their patient rights. In the previous usage of the BAMHS scale, there was a mild statistically significant correlation in the paternalism subscale and the age of participants. Additionally, that study had a second follow-up where no differences were observed on the subscales, except with adult mental health participants.21

Tolerance and Discrimination

Our research showed that HCPs discriminate against people who have severe mental illnesses, with half of them believing that service users should not be allowed to vote and that it would be uncomfortable to be friends with them. The right to vote, which is a significant symbol of citizenship, is an integral part of recovery-based behaviors since the entire process makes people feel like they are part of a community.32 Therefore, access to healthcare for both physical and mental disorders should be seen as a fundamental human right. Participants also reported much lower levels of comfort when a teacher had a mental disorder. This suggests a greater degree of social distance as well as employment discrimination. Eliminating people with mental disorders from the workforce lowers self-esteem, encourages isolation, and marginalizes the population of a society.33 For fear of being judged, many people avoid treatment for mental disorders.8 However, because stigma in mental health therapy makes individuals reluctant to seek treatment, it increases the severity of mental disorders.34

Study Limitations

Among the limitations, our sample was limited to specific public HCPs, which is not representative of all in the UAE. In addition to that, we think that selection bias may be an issue due to the non-random selection of the study population, which may affect the obtained results and limit the generalizability of the study findings. Only beliefs and attitudes, not actual behaviors, were explored. Future research should look into whether training directly impacts HCPs’ clinical practice, as well as how anti-stigma programs can legitimately pursue HCPs’ self-interest. Future studies may consider a larger sample size of the population and a random sample selection approach.

Conclusions

Although it would be premature to generalize the findings for all HCPs, the study’s goal was to raise awareness about the beliefs and attitudes of HCPs towards service users’ rights in seeking treatment. Our findings show that HPCs understand mental disorders, and believe in individuals’ rights and freedoms should be equal to those who do not have mental disorders, but there is a degree of discrimination and a high level of social distance. HCPs are less tolerant when interacting with those with mental disorders outside their professional lives. Although the results indicate that HCPs accept people with mental disorders, interventions with long-term follow-up activities should be offered to improve HCPs’ capacity to better serve service users. These activities include collaborative care and discrimination awareness programs to educate the community.

Abbreviations

HCP, healthcare providers; UAE, United Arab Emirates; BAMHS, The Health Professionals Beliefs and Attitudes towards Mental Health Users’ Rights Scale; OECD, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; CI, confidence interval; Expat, expatriate; OR, odds ratio.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The aims and procedures of data collection were approved by the Research Committee of Higher Colleges of Technology, Dubai, UAE, as part of an interdisciplinary research grant (Fund No. 113120). The participants autonomously decided to participate voluntarily. Informed consent was presented where participants had to check off for acknowledgment before filling in the survey. The research purposes were explained. Since the survey was sent electronically over email as a SurveyMonkey link, participants’ responses’ privacy and confidentiality were protected. Additionally, nobody outside the research team was informed of the participant’s involvement.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of Profs. Vikram Patel and Shekhar Saxena of Librum in the methodology for this study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. de Jacq K, Norful A, Larson E. The variability of nursing attitudes toward mental illness: an integrative review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;30(6):788–796. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2016.07.004

2. Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2014;45(1):11–27. doi:10.1017/s0033291714000129

3. Hansson L, Jormfeldt H, Svedberg P, Svensson B. Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards people with mental illness: do they differ from attitudes held by people with mental illness? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;59(1):48–54. doi:10.1177/0020764011423176

4. Hamilton S, Pinfold V, Cotney J, et al. Qualitative analysis of mental health service users’ reported experiences of discrimination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(S446):14–22. doi:10.1111/acps.12611

5. Corrigan P, Druss B, Perlick D. The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2014;15(2):37–70. doi:10.1177/1529100614531398

6. Barrett M, Chua W, Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons M, Thompson D. Early withdrawal from mental health treatment: implications for psychotherapy practice. Psychotherapy. 2008;45(2):247–267. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.247

7. Sheehan L, Nieweglowski K, Corrigan P. Structures and types of stigma. In: The Stigma of Mental Illness—End of the Story? Cham, Swtizerland: Springer; 2017:43–66.

8. Corker E, Hamilton S, Henderson C, et al. Experiences of discrimination among people Using mental health services in England 2008–2011. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(s55):s58–s63. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112912

9. Webster N. New mental health strategy in Dubai targets service shortfall. The National; 2019. Available from: https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/health/new-mental-health-strategy-in-dubaitargets-service-shortfall-1.816165.

10. Abdel Aziz K, Aly El-Gabry D, Al-Sabousi M, et al. Pattern of psychiatric in-patient admissions in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. BJPsych Int. 2020;18(2):46–50. doi:10.1192/bji.2020.54

11. Haque A, Kindi B. Mental health system development in the UAE. In: Mental Health and Psychological Practice in the United Arab Emirates. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2015:23–34. doi:10.1057/9781137558237_3

12. Dubai Health Authority. Dubai clinical services capacity plan 2018–2030. Dubai: Dubai Government; 2018. Available from: https://www.dha.gov.ae/DHAOpenData/Annual%20Statistical%20Books/DHADoc1260173559-03-06-2020.pdf.

13. US-UAE Business Council. The UAE healthcare sector. Washington, DC; 2021. Available from: http://www.usuaebusiness.org/publications/2019-uae-healthcare-sector-report/.

14. Petkari E, Ortiz-Tallo M. Towards youth happiness and mental health in the United Arab Emirates: the path of character strengths in a multicultural population. J Happiness Stud. 2016. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9820-3

15. Keller A, Gangnon R, Witt W. The impact of patient–provider communication and language spoken on adequacy of depression treatment for U.S. women. Health Commun. 2013;29:646–655. doi:10.1080/10410236.2013.795885

16. Economou M, Peppou L, Kontoangelos K, et al. Mental health professionals’ attitudes to severe mental illness and its correlates in psychiatric hospitals of Attica: the role of workers’ empathy. Community Ment Health J. 2019;56(4):614–625. doi:10.1007/s10597-019-00521-6

17. Solmi M, Granziol U, Danieli A, et al. Predictors of stigma in a sample of mental health professionals: network and moderator analysis on gender, years of experience, personality traits, and levels of burnout. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63(1). doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2019.14

18. Flanagan E, Miller R, Davidson L. “Unfortunately, we treat the chart:” sources of stigma in mental health settings. Psychiatric Quart. 2009;80(1):55–64. doi:10.1007/s11126-009-9093-7

19. Renedo A, Marston C. Spaces for citizen involvement in healthcare: an ethnographic study. Sociology. 2014;49(3):488–504. doi:10.1177/003803851454420810.3389/fpsyg.2017.01020

20. Eiroa-Orosa F, Rowe M. Taking the concept of citizenship in mental health across countries. reflections on transferring principles and practice to different sociocultural contexts. Front Psychol. 2017;8. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01020

21. Eiroa-Orosa F, Lomascolo M, Tosas-Fernández A. Efficacy of an intervention to reduce stigma beliefs and attitudes among primary care and mental health professionals: two cluster randomised-controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1214. doi:10.3390/ijerph18031214

22. Eiroa-Orosa F, Limiñana-Bravo L. An instrument to measure mental health professionals’ beliefs and attitudes towards service users’ rights. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(2):244. doi:10.3390/ijerph16020244

23. Team R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: Team R; 2017.

24. Loch A, Rössler W. Who is contributing? In: In the Stigma of Mental Illness-End of the Story? Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017:111–121.

25. Harangozo J, Reneses B, Brohan E, et al. Stigma and discrimination against people with schizophrenia related to medical services. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;60(4):359–366. doi:10.1177/0020764013490263

26. Thornicroft G. Stigma and discrimination limit access to mental health care. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2008;17(1):14–19. doi:10.1017/s1121189x00002621

27. Abi Hana R, Arnous M, Heim E, et al. Mental health stigma at primary health care centres in Lebanon: qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2022;16(1). doi:10.1186/s13033-022-00533

28. Thombs B, Adeponle A, Kirmayer L, Morgan J. A brief scale to assess hospital doctors’ attitudes toward collaborative care for mental health. Canad J Psychiatry. 2010;55(4):264–267. doi:10.1177/070674371005500410

29. Corrigan P, Edwards A, Green A, Diwan S, Penn D. Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27(2):219–225. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006868

30. Sreeram A, Cross W, Townsin L. Anti‐stigma initiatives for mental health professionals—A systematic literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2022;29:512–528. doi:10.1111/jpm.12840

31. Lauber C, Nordt C, Braunschweig C, Rossler W. Do mental health professionals stigmatize their patients? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(s429):51–59. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00718.x

32. Lawn S, McMillan J, Comley Z, Smith A, Brayley J. Mental health recovery and voting: why being treated as a citizen matters and how we can do it. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2013;21(4):289–295. doi:10.1111/jpm.12109

33. Stuart H. Mental illness and employment discrimination. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(5):522–526. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000238482.27270.5d

34. Schulze B. Stigma and mental health professionals: a review of the evidence on an intricate relationship. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):137–155. doi:10.1080/09540260701278929

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.