Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 7

Australian physiotherapists and their engagement with people with chronic pain: do their emotional responses affect practice?

Received 3 December 2013

Accepted for publication 13 February 2014

Published 29 May 2014 Volume 2014:7 Pages 231—237

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S58656

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Shelley Barlow, John Stevens

Health and Human Sciences, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW, Australia

Abstract: This study explores the experiences of Australian physiotherapists who see people with chronic pain as part of their daily practice. It has been established in the literature that Australian physiotherapists do not manage people with chronic pain well; however, the reasons for this are not well understood. This study aimed to explore this phenomenon through a qualitative approach that generated data about the perceptions of physiotherapists in regard to caring for people with chronic pain. Fourteen physiotherapists were interviewed using a semi-structured interview approach. The results indicate that the therapists experience emotional responses to people with chronic pain, which lead to difficulties in being able to successfully provide effective care. These findings also provide the beginnings of a framework that may support physiotherapists in engaging more successfully with people with chronic pain.

Keywords: physiotherapist perceptions, clinical practice, emotional engagement

Introduction

Outpatient physiotherapists are well placed to work with people with chronic pain.1 Chronic pain (CP) or pain that has been experienced daily for 3 or more months is prevalent within our communities and is often one of the main reasons for referral.2,3 The number of people referred to physiotherapy as outpatients with chronic pain is increasing, which is in line with the current trends in industrialized countries of aging populations and increases in chronic disease and pain.4,5

Multiple recent studies indicate that, despite a significant increase in guidelines, literature, and access to information, physiotherapists struggle with the application of evidence-based chronic pain management (EB CPM) in everyday practice.6–10

Daykin and Richardson,11 in their study of physiotherapists’ pain beliefs, suggest that a physiotherapist’s pain beliefs will affect their behavior. If they continue to construct the encounter from a biomedical belief system, then their behavior and clinical decisions will reflect this orientation.

However, the literature states very clearly that a biopsychosocial orientation as part of EB CPM provides greater potential for recovery of disability and well-being for people with CP.12–14 While studies have focused on pain beliefs, cognitions, and emotions in health professionals in relation to people with CP, few look specifically at physiotherapists’ personal perceptions and their impacts.15

A range of issues encountered by physiotherapists in working with outpatients with CP were raised in the document Physiotherapy outpatient’s chronic pain management ……. realizing the potential by Barlow.16 While there are many issues based on the context of outpatients, this article explores whether the emotional issues prevent deeper engagement by physiotherapists with people with CP.

According to Australian best practice guidelines, EB CPM requires a program of: biopsychosocial assessment; identification of risk factors; cognitive behavioral therapy and functional restoration; eliciting patient commitment using an interdisciplinary and partnership approach; and underpinning patient education with therapeutic neuroscience.17–21

The therapeutic relationship is regarded as fundamental within all clinical encounters; this is a fundamental difference between the biomedical and biopsychosocial models. Within the field of pain medicine, Cohen and Quinter take this transaction to be central:

We identify the clinical encounter as the central transaction in pain medicine: the presentation of a person distressed because of a profound threat to their bodily integrity to another person reputed to be learned in the art of healing.22

This orientation stresses a relationship of trust and safety as central to effective therapy. Unless the physiotherapist knows to what degree the psychosocial issues are impacting on the life of a person with CP, then important areas for healing are missed. Inquiry into patients’ subjective experiences, which include their emotional state, will often require the physiotherapist to remain open to distress and suffering according to Cohen and Quinter. This in itself may be challenging to the physiotherapists.

Cohen and Quinter described the emotional impacts on physiotherapists working with people with CP.22 They found that there appears to be a struggle for those physiotherapists, in the context of this environment, to move beyond the structural components of the body and symptom reduction in order to recognize the manifestations of an aberrant neural system and the corresponding psychosocial impacts. To do so requires an understanding of the power of active engagement in pain management that is alternate to that which physiotherapists seem to develop as part of their practice.23

This study therefore aims to explore this apparent limitation in the practice potential of physiotherapists. This is a qualitative study that explores the subjective experiences, feelings, and behaviors of physiotherapists in regard to caring for people with CP.24–28

Methods

A qualitative approach was chosen to explore and understand the contextual, professional, and personal aspects related to outpatient physiotherapists’ clinical practice.29

Phenomenology aims, in the words of Crotty, to provide a “study of experiencing individuals”.30 This study facilitated an in-depth exploration of the physiotherapists’ observations, perceptions, impressions, and emotional and cognitive responses.31

The first person subjective approach of phenomenology provides knowledge or the facts about the physiotherapists’ experiences.

An interpretive perspective allowed understanding and empathy to unfold for the physiotherapists working in this context.30 The researcher’s background as an outpatient physiotherapist who had previously worked in a pain clinic provided the background for the inquiry.

Sampling and sample

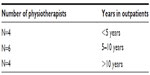

Convenience sampling was used. An e-mail asking for volunteers was sent to all physiotherapists in the local health area nearest the researcher (Northern New South Wales Local Health District); there were 15 replies out of a possible 50 outpatient physiotherapists. Fourteen physiotherapists met the criteria of working with outpatients in an outpatient department; one did not and was excluded (Table 1). All physiotherapists received an information sheet and consent form.

| Table 1 Physiotherapists’ years working in outpatients |

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken. The interviews occurred in a quiet room at the physiotherapist’s place of work within work time to provide insight into the naturalistic setup of the physiotherapy outpatient departments. The interviews were completed using an interview schedule, which contained prompting questions where required, and were recorded.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim. They were handed back to the participants to read for verification and amendments were then made, where required, by the participant. These transcripts were analyzed post-interview using thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke.32

Types of questions

The full list of questions used in the interview schedule is included as Figure S1. Questions included: what does CP management mean to you; how do you work with someone who has CP; what do you enjoy or find difficult when working with people with CP; have you had any training in using EB CPM; and if you could work differently with people with chronic pain, what would this look like? Additional questions were used for prompts as needed to explore more fully some of the answers.33

Data analysis

The thematic analysis was informed by Braun and Clarke and involved constant comparison of the data.32 Transcripts were read and reread for coding. Open coding was utilized and descriptive memos were produced. Memos were summarized and charted into matrices with their corresponding quotes. Common themes were coded accordingly. Axial coding produced further categories and sub codes.

Ethics

Low risk ethics approval was received in November 2010 (number NCAHS LNR002).

Results

The physiotherapists ranged in experience from 1 year post-graduate to 30 years of working life. Very small remote sites of only one or two physiotherapists to larger sites of eight or nine physiotherapists were represented. There did not appear to be obvious differences in responses that could be linked to age or years of experience.

The emergent themes

Frustration

Frustration was connected to a perceived lack of knowledge and expertise in working with people with CP.

I find it is an area that frustrates all the people that come into outpatients for all the reasons, they are not well educated in the area, where people have a deficit in their knowledge, not sure what they are doing the patient gets bounced from person to person. [Participant 1]

Stress and isolation from meeting expectations

Physiotherapists working in rural and regional physiotherapy outpatients experience stress and isolation.

A bit stressful at times, how can you fix me if don’t know the answers, lose confidence from patient and self. [Participant 2]

Despair

People with CP are seen as intellectually challenging, but can create feelings of despair in the physiotherapists if they are depressed and are difficult to engage in the strategies. The physiotherapists find that treating depressed and reluctant participants has an effect on their own mood, often leaving them feeling hopeless and helpless; the very feelings people with CP often complain of.

I think in terms of physio outpatients departments … are essentially rural departments, we are generalist physios that cover numerous different case loads and we are not essentially specialist in any area so chronic pain is another case with the other ten for example that requires probably a bit more than all the others that we just don’t have the expertise in. [Participant 9]

I find it a challenge (working with people with CP when distressed) so I like that aspect of it but particularly when you get a couple in a row (people with CP) it can get you down and affect how you are feeling. [Participant 2]

Wariness

The physiotherapists are uncomfortable when communicating with people with CP when people with CP are emotionally distressed. These quotes highlight the cautious communication strategies physiotherapists adopt when working with people who are distressed to minimize any misunderstandings and avoid further emotional distress in the patients and physiotherapists.

… particularly with chronic pain ones when they are quite upset and you have to be very careful about the way you speak about what plans are and what goes on with them. [Participant 2]

Unfortunately you hear them, I’ve had patient’s been to various pain clinics, simply haven’t accepted it (EB CPM) can be extremely angry or whatever been to these places and they have been told “get on with life” they don’t understand and if you’re not careful you simply antagonize them. [Participant 4]

Avoidance

Experiencing people with CP as negative can lead to avoidance of engagement. This can influence clinical decision-making and whether or not EB CPM strategies are included in the episode of care.34–36

Because I don’t like opening a can of worms, I’m not a clinical psychologist I became a physio. I have lots of experience I see the flags (yellow flags or psychological issues) I don’t back away, I don’t confront and try and use any taught techniques and I never try to learn anything in that area. [Participant 4]

Yellow flags that are really quite difficult and sometimes I feel it’s the yellow flags type that I just say you need to go to the chronic pain clinic. [Participant 9]

Isolation

Even with training, physiotherapists are reluctant to commit to working with people with CP and implementing EB CPM.

I wouldn’t like to do the extra training and then being the only one who deals with it. [Participant 2]

Difficulty accessing other health professionals

I’m a physio I’m not a psych and there are psychologists out there who can do good stuff with chronic pain and I’m just a rural physio we don’t have access to psych’s (psychologists) who specialize in chronic pain. [Participant 7]

Physiotherapists can be successful

However, it is recognized that physiotherapists are equipped to work closely with people with CP using a cognitive behavioral approach as often rapport is already established. Some physiotherapists thought this approach was outside their scope of practice. Some physiotherapists already utilize a cognitive behavioral approach.34–40

Having a psychologist real advantage, using CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) approach, physios not trained, although it is a hall mark of how physio in general manage people in a way recon they are already doing it to some extent. [Participant 5]

Discussion

This study explored the subjective experiences of outpatient physiotherapists working with people who have CP. Fourteen physiotherapists with a broad range of experience and age were interviewed. Most (N=10) physiotherapists interviewed expressed difficulties working with people with CP. Some of the physiotherapists who engaged with people with CP on an emotional level had had more experience working with people with CP. They had worked or observed in a pain clinic, had worked closely with pain specialist physiotherapists, or had initiated self-directed learning and had started their own pain programs. This suggests an increased capacity to work closely with a broader focus and to include potential exploration of psychosocial issues without reacting.

This research has revealed that working with people with CP and integrating EB CPM into outpatient clinical practice can be frustrating, confusing, and difficult for some physiotherapists. The physiotherapists felt that they were unskilled and under-resourced to deal with people with CP. Their lived experiences were shaped by the roles and responsibilities of being an outpatient physiotherapist; often there is little exposure to alternative models of pain management and, if there is, then the art of integrating new approaches without adequate support is stressful.37–38

Unless there has been a concerted effort by the physiotherapist’s post-graduation professional and personal development, the bias of professional training continues to ignore the relational aspects of CP management. Appropriate relational skills are not developed, making transition from an expert oriented role to a collaborative partnership role that is more aligned with EB CPM challenging.

These findings are consistent with literature that states that physiotherapists have difficulty working in a holistic way with people with CP.34,39 The inability to look past the immediate physical presentations and take into account the neurophysiological and biopsychosocial factors is widespread amongst physiotherapists and a contributing factor to poor implementation of EB CPM.36,41–45

If there is adequate identification, appreciation, and management of the psychosocial issues within physiotherapy outpatients, then relational skills training would become more apparent.

This research indicates that physiotherapists may find that they are more able to engage with people with CP when they adopt EB CPM. Utilizing this approach may change how physiotherapists feel about working with people with CP. Future research may examine physiotherapists before and after adopting EB CPM with an emphasis on the interpersonal aspects and see if this supports deeper engagement.44–52

Limitations

The study focused on the challenges of physiotherapists working in public hospital outpatient settings and did not have the scope to explore this phenomenon in other settings such as private clinics. These other settings are an obvious area for further exploration.

Another limitation of this study is due to the researcher working in the same outpatient setting (not necessarily the same location) as the physiotherapists that were interviewed. The position of an insider observer may prevent the recognition and appreciation of themes that may be clearer to someone from an outsider position. As an exploratory qualitative study with a sample size of 14, the results are unable to be generalized; however, the theory generated by this research may be the focus of future, larger projects.

Conclusion

The physiotherapists’ experiences provide data for future planning. Utilizing outpatient physiotherapists’ subjective experiences will allow clinical processes to reflect the reality of clinical practices and how they can be more responsive and less reactive to people with CP. The ability to interact effectively with people with CP remains one of the most powerful opportunities for professional and patient satisfaction and healing.40

The findings in this report are timely. The March Physiotherapy Journal of Australia (2012) has highlighted the “need for pain education for all physiotherapists” regardless of where they work.15,51

When people with CP expressed emotional distress, physiotherapists who were less certain about working with people with CP were more likely to avoid deepening their engagement and tended to refer them on to counselling services. They expressed doubts about their abilities to help under these circumstances.

Avoidance further reinforced the lack of engagement by physiotherapists with psychosocial aspects of physiotherapy. It is well known in the literature that, if these areas are addressed, there are greater therapeutic outcomes. EB CPM has stronger therapeutic effects than conventional biomedical or biomechanical modalities, and it can be a supportive framework for physiotherapists to broaden their contact with people with CP.

However, despite the literature suggesting that a change in practice to a biopsychosocial model was necessary for EB CPM and physiotherapist uptake is variable and physiotherapists in this study struggled with the concepts and implementation.

While these results cannot be generalized to a wider population, the difficulties encountered by the physiotherapists in this study highlight an area for deeper exploration. Further exploration may reveal what physiotherapists need apart from knowledge to enable them to engage with people with CP in a more satisfying way. Physiotherapy may benefit from explicit training in the emotional and relational engagement skills that are needed when working with people with CP.

Do physiotherapists who update their knowledge of EB CPM have a greater chance of minimizing their own emotional distress and improving their engagement with people with CP? Further research on questions like this would provide a greater depth of understanding of the daily challenges that outpatient physiotherapists experience that contribute to the poor utilization of EB CPM.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Sanders T, Foster NE, Bishop A, Ong BN. Biopsychosocial care and the physiotherapy encounter: physiotherapists’ accounts of back pain consultations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:65. | |

Stevenson K, Lewis M, Hay E. Does physiotherapy management of low back pain change as a result of an evidence-based educational programme? J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(3):365–375. | |

Blyth FM, March LM, Nicholas MK, Cousins MJ. Self-management of chronic pain: a population-based study. Pain. 2005;113:285–292. | |

Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Das A, McAuley JH. Low back pain research priorities: a survey of primary care practitioners. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:40. | |

Wang H, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Lofgren KT. Age-specific and sex-specific mortality in 187 countries, 1970–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2071–2094. | |

Brunner E, De Herdt A, Minguet P, Baldew SS, Probst M. Can cognitive behavioural therapy based strategies be integrated into physiotherapy for the prevention of chronic low back pain? A systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(1):1–10. | |

Nicholas M, Molloy A. Chronic pain control, integrating medical and psychosocial treatment options. New Ethics Journal. 2002;2:33–40. | |

Siddall PJ, Cousins MJ. Persistent pain as a disease entity: implications for clinical management. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:510–520. | |

Sluka KA. General principles of physical therapy practice in pain management. In: Sluka KA, editor. Mechanisms and Management of Pain for the Physical Therapist. Seattle: ISAP Press; 2009:133–142. | |

Moseley L. Combined physiotherapy and education is efficacious for chronic low back pain. Aust J Physiother. 2002;48:297–302. | |

Daykin AR, Richardson B. Physiotherapists’ pain beliefs and their influence on the management of patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:783–795. | |

Henry JL. The need for knowledge translation in chronic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:465–476. | |

Hay EM1, Mullis R, Lewis M, et al. Comparison of physical treatments versus a brief pain-management programme for back pain in primary care: a randomised clinical trail in physiotherapy practice. Lancet. 2005;365:2024–2030. | |

Waddell G. 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences. A New Clinical Model for the Treatment of Low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12(7):632–644 | |

Austin T. Pain education is required for all physiotherapists. J Physiother. 2012;58:64. | |

Barlow SE. The barriers to implementation of evidence-based chronic pain management in rural and regional physiotherapy outpatients. Realising the potential. HETI Report. Rural research capacity building program. NSW Ministry of Health. 2012. Available from: www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au. Accessed May 15, 2014. | |

Cousins M. 2010 National Pain Strategy: Pain Management for all Australians. Melbourne: National Pain Summit; 2010. Available from: http://www.iasp-pain.org/files/Content/NavigationMenu/Advocacy/InternationalPainSummit/Australia_2010PainStrategy.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2014. | |

NSW Ministry of Health. NSW Pain management plan 2012–2016-NSW Government Response to the pain management. Taskforce report. NSW: NSW Ministry of Health; 2012. Available from: http://www0.health.nsw.gov.au/pubs/2012/pdf/nsw_pain_management_plan_.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2014. | |

Lavand’homme P. The progression from acute to chronic pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24:545–550. | |

Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(5):535–544. | |

Overmeer T, Boersma K, Denison E, Linton SJ, Does teaching physical therapists to deliver a biopsychosocial treatment program result in better patient outcomes? A randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):804–819. | |

Cohen M. Quintner J. Making sense of Pain, Critical and interdisciplinary perspectives. Fernandez J, editor. In: The clinical conversation about pain: tensions between the lived lived experience and the biomedical model. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press; 2010. Available from: http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/pain2010ever11007102.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2014. | |

Linton SJ, Shaw WS. Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):700–711. | |

Critchley DJ1, Ratcliffe J, Noonan S, Jones RH, Hurley MV. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three types of physiotherapy used to reduce chronic low back pain disability: A pragmatic randomized trial with economic evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(14):1474–1481. | |

Jack K1, McLean SM, Moffett JK, Gardiner E. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15(3):220–228. | |

Kainz B, Gülich M, Engel EM, Jäckel WH. [Comparison of three outpatient therapy forms for treatment of chronic low back pain – findings of a mulitcentre, cluster randomized study]. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 2006;45(2):65–77. German. | |

Lederman E. The fall of the postural-structural-biomechanical model in manual and physical therapies: exemplified by lower back pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2011;15(2):131–138. | |

Moffett J, McLean S. The role of physiotherapy in the management of non-specific back pain and neck pain. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:371–378. | |

Coyle N, Tickoo R. Qualitative research: what this research paradigm has to offer to the understanding of pain. Pain Med. 2007;8(3):205–206. | |

Crotty M. The foundations of Social Research. London: Sage publications; 1998. | |

Zeelenberg M, Nelissen RM, Breugelmans SM, Pieters R. On emotion specificity in decision making: why feeling is for doing. Judgement and Decision-Making. 2008;3:18–27. | |

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. | |

Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods – whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. | |

Nicholas MK, George SZ. Psychologically informed interventions for low back pain: an update for physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2011;91:765–776. | |

Kenny DT. Constructions of chronic pain in doctor-patient relationships: bridging the communication chasm. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:297–305. | |

Main CJ, George SZ. Psychological influences on low back pain: why should you care? Phys Ther. 2011;91:609–613. | |

Apkarian V. Low Back Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain: Pain Clinical Updates. 2010; XV111(6):1–6. | |

Keefe FJ, Somers TJ. Coping with Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain: Pain Clinical Updates. 2009; XV11(5):1–5. | |

Craik RL. A convincing case – for the psychologically informed physical therapist. Phys Ther. 2011;91:606–608. | |

Tonkin L, Molloy A. The role of physiotherapy in managing chronic nonmalignant pain. MedicineToday. 2003;suppl:27–31. | |

Woby SR, Roach NK, Urmston M, Watson PJ. 2008 Outcome following a physiotherapist-led intervention for chronic low back pain: the important role of cognitive processes. Physiotherapy. 2008;94(2):115–124. | |

Loeser JD. Five crises in pain management. International Association for the Study of Pain: Pain Clinical Updates. 2012;20:1. | |

Arendt-Nielsen L, Barbe MF, Bement MH, et al. Global year against musculoskeletal pain. International Association for the Study of Pain: Assessment of Musculoskeletal Pain: Experimental and Clinical. 2010. | |

Jamison R. Non-specific treatment effects in pain medicine. International Association for the Study of Pain: Pain Clinical Updates. 2011;14. | |

Sluka KA, Turk DC. Invited Commentary. Phys Ther. 2009;89:470–472. | |

Takeuchi R, O’Brien MM, Ormond KB, Brown SD, Maly MR. “Moving forward”: Success from a physiotherapist’s point of view. Physiother Can. 2008;60(1):19–29. | |

Slater H, Briggs A. Physiotherapists must collaborate with other stakeholders to reform pain management. J Physiother. 2012;58:65. | |

Potter MB. Chronic Pain Management: Practical Tips and Guidelines for Primary Care. Advanced Studies in Medicine. 2004;4(1):31–40. | |

Albaladejo C, Kovacs FM, Royuela A, del Pino R, Zamora J, Spanish Back Pain Research Network. The efficacy of a short education program and a short physiotherapy program for treating low back pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(5):483–496. | |

Sandborgh M, Asenlof P, Lindberg P, Denison E. Implementing behavioural medicine in physiotherapy treatment. Part II: Adherence to treatment protocol. Adv Physiother. 2010;12(1):13–23. | |

Physiotherapy 2012: Physios need to adopt a new pain paradigm [webpage on the Internet]. London: Chartered Society of Physiotherapy; 2012. Available from: http://www.csp.org.uk/news/2012/10/18/physiotherapy-2012-physios-need-adopt-new-paradigm. Accessed May 16, 2014. | |

Alford L. Psychoneuroimmunology for physiotherapists. Physiotherapy. 2006;92(3):87–191. |

Supplementary material

| Figure S1 Example of Interview Schedule. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.