Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 11

Attitudes of psychiatrists toward obsessive–compulsive disorder patients

Authors Kusalaruk P, Saipanish R , Hiranyatheb T

Received 26 March 2015

Accepted for publication 18 May 2015

Published 15 July 2015 Volume 2015:11 Pages 1703—1711

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S85540

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 5

Editor who approved publication: Professor Wai Kwong Tang

Pichaya Kusalaruk, Ratana Saipanish, Thanita Hiranyatheb

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Purpose: Negative attitudes from doctors and the resulting stigmatization have a strong impact on psychiatric patients’ poor access to treatment. There are various studies centering on doctors’ attitudes toward psychiatric patients, but rarely focusing on the attitudes to specific disorders, such as obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). This research aimed to focus on psychiatrists’ attitudes toward OCD patients.

Patients and methods: The participants were actual psychiatrists who signed a form of consent. The main tool used in this study was a questionnaire developed from a focus group interview of ten psychiatrists about their attitudes toward OCD patients.

Results: More than 80% of the participating psychiatrists reported a kindhearted attitude toward OCD patients in the form of pity, understanding, and empathy. Approximately one-third of the respondents thought that OCD patients talk too much, waste a lot of time, and need more patience when compared with other psychiatric disorder sufferers. More than half of the respondents thought that OCD patients had poor compliance with behavioral therapy. The number of psychiatrists who had confidence in treating OCD patients with medications (90.1%) was much higher than those expressing confidence in behavioral therapy (51.7%), and approximately 80% perceived that OCD patients were difficult to treat. Although 70% of the respondents chose medications combined with behavioral therapy as the most preferred mode of treatment, only 7.7% reported that they were proficient in exposure and response prevention.

Conclusion: Even though most psychiatrists had a more positive than negative attitude toward OCD patients, they still thought OCD patients were difficult to treat and had poor compliance with behavioral therapy. Only a small number of the participating psychiatrists reported proficiency in exposure and response prevention.

Keywords: obsessive–compulsive disorder, psychiatrist, attitude, stigma, Thai

Introduction

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is the fourth most common psychiatric illness, with a lifetime prevalence of 1%–3%.1 The World Health Organization rates OCD as one of the top 20 most disabling diseases.2 If untreated, the course is usually chronic, or waxing and waning. Only approximately one-third of OCD patients receive appropriate pharmacotherapy, and fewer than 10% receive evidence-based psychotherapy.1 As OCD patients often acknowledge the senseless nature of their intrusive, recurrent thoughts and also the repetitive, unwanted behaviors, it may lead to shame, and reluctance to seek help.2 People with this disorder have long delays in accessing effective treatments; 17 years on average in one study.2 There is growing evidence that stigmatization and negative attitudes toward mental disorders are important factors that prevent these patients from seeking appropriate medical help.3–7 Aversion to psychiatric treatment and ambivalence about mental health services because of the fear of labeling and stigma have been found throughout the world.8

In addition, medical professional attitudes might impact the quality of treatment as well as the outcome. Various studies on doctors’ attitudes toward psychiatric patients, including psychiatrists’ attitudes, brought out some discordant findings.9 Gateshill et al reported that the majority of mental health and nonmetal health professions felt sympathy for those with mental disorders, wanting to help them, and favoring their treatment in the community.4 However, some studies suggested that psychiatrists tended to have more positive attitudes toward mentally ill patients than nonmetal health professionals did.4,10,11 Arvaniti et al found that familiarity with mental illness was associated with less negative attitudes, such as less social discrimination and less social restriction, in which case psychiatric staff had more positive attitudes than other staff.10 Addison and Thorpe studied the factors involved in the formation of attitudes toward mentally ill patients and found that people who had personal experience with mental illness sufferers were generally more positive in their attitudes than those who had no previous experience.11 In contrast, some studies revealed that psychiatrists had negative attitudes toward psychiatric patients, which resembles the attitude of other doctors and general public.12–14

While there have been a variety of studies on the attitudes toward general psychiatric patients, and some studies on schizophrenia or major depression,12,13 rarely have the attitudes toward OCD been focused on. We found only one study by Simonds and Thorpe in 2003 about the attitudes toward the different subtypes of OCD symptoms, for which undergraduate students were used as subjects.15 Vignettes of different subtypes of OCD symptoms were used, and it was found that the vignette describing a person with doubting, violent, and blasphemous obsessions and related compulsions received the more negative social evaluations when compared with the vignette describing a person with cleansing rituals and checking compulsions.15 To our knowledge, no studies focusing on the attitudes of psychiatrists toward OCD patients have been published before. Therefore, our research aimed to specifically study psychiatrists’ attitudes toward OCD patients.

Patients and methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok. The participants were actual psychiatrists who were willing to attend the study. Exclusion criteria were mainly directed to those psychiatrists who had close friends or relatives diagnosed with OCD, or had themselves been diagnosed with OCD before. The participants were invited to this study by direct invitation or by mail. All participants provided their written informed consent before participating in the study.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed from a focus group interview of ten psychiatrists which centered on their attitudes and feelings toward OCD patients, and the different emotions or perceptions when compared with those prevalent when facing other psychiatric disorder sufferers. The data were then transformed into a self-reported questionnaire, which consisted of three parts. The first part is about the socio-demographic information of the psychiatrists, such as sex, age, duration of practice as a psychiatrist, workplace, and the estimated number of outpatients they have seen in one period (approximately 3 hours). The second part centers on their experience with OCD patients including the estimated number of OCD patients they used to have experience in treatment, the estimated time spent with OCD patients at their first visit and in follow-up sessions, their preferred mode of treatment for OCD, their experience and proficiency in exposure and response prevention (ERP), and finally their confidence in treating OCD patients with various approach. The third part concerns their attitudes toward OCD patients, reflected in 16 items to reply to, according to the four-point Likert scales ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. More specifically, there are seven items about the attitudes and feelings toward OCD patients, three items about their perceptions toward OCD patients’ compliance, and six items regarding the emotions and perceptions toward OCD patients comparing with patients with other psychiatric disorders.

A statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 18 for Windows XP (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Psychiatrists’ characteristics and experience with OCD patients were reported by frequency; all attitude items were reported in percentage. Pearson’s chi-squared (χ2) test and Fisher’s exact test (FET) were used to analyze the association between psychiatrists’ characteristics and their attitudes toward OCD patients.

Results

Questionnaires were distributed to 203 Thai psychiatrists directly or by mail. One hundred and three of them (50.7%) sent back their questionnaires. Twelve psychiatrists were excluded due to having relatives diagnosed with OCD; as a result, 91 psychiatrists remained in the study.

Psychiatrist’s characteristics

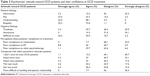

Most of the participating psychiatrists were female (63.7%), and approximately 80% were under the age of 45. Almost half of them (44%) have been practicing as a psychiatrist for less than 5 years. They have been working in 32 different hospitals all over Thailand, which included 15 psychiatrists from northern area, 9 psychiatrists from southern area, 5 psychiatrists from northeastern area, 4 psychiatrists from western area, and 48 psychiatrists from middle area of Thailand. The remaining 10 psychiatrists reported only the type of hospitals they have been working for, but did not specify their hospital name. Regarding the types of hospital, the largest group of participants (41.8%) has been practicing in 19 different general/provincial hospitals, followed by 29.7% in seven different medical university hospitals, 25.3% in four different mental hospitals, and 3.3% from private hospital or others. Almost half of them (47.3%) estimated the number of outpatients they treated per period (3 hours) to be more than 30 (Table 1).

| Table 1 Psychiatrists’ characteristics and experience with OCD patients |

Experience with OCD patients

Approximately 40% of the participating psychiatrists had experience in treatment for fewer than 10% OCD patients. About half of them spent approximately 15–30 minutes for the first visit with OCD patients, and less than 15 minutes for follow-up sessions. Approximately 70% of the psychiatrists chose medications combined with behavioral therapy as the most preferred mode of treatment. Only 7.7% of them reported that they were proficient in ERP, whereas almost 70% of the participants reported using ERP for their patients but were not proficient in it. Most of the psychiatrists (76.9%) had confidence in treating OCD patients, but the number of psychiatrists who had confidence in treating with medications (91.1%) was much higher than those expressing confidence in behavioral therapy (51.7%) and other psychotherapy (39.6%) (Table 1).

Attitudes toward OCD patients

More than 80% of the participating psychiatrists agreed with the benevolent attitudes toward OCD patients such as pity, understanding, and empathy, but only 18.7% stated that these patients were admirable. In term of negative attitudes, 33% of psychiatrists felt tired when treating OCD patients, and 14.3% felt these patients were annoying. Up to 80% of them reported that OCD patients were difficult to treat. The number of psychiatrists who perceived that OCD patients had poor compliance with behavioral therapy (52.8%) and other psychotherapy (30%) was higher than those reporting poor compliance with medications (7.7%). When compared with other psychiatric disorders, approximately 30% of psychiatrists thought that OCD patients talk too much, ask too much, need more time and patience, and 14% reported that they do not really want to treat OCD patients. Only 7.7% stated that building therapeutic relationship with these patients was more difficult than in the case of other psychiatric disorder sufferers (Table 2).

| Table 2 Psychiatrists’ attitude toward OCD patients and their confidence in OCD treatment |

Psychiatrists’ characteristics that influenced the attitudes

Degree of association between all characteristics and attitudes and level of statistically significant difference are shown in Tables S1–S3.

General characteristics

Some psychiatrists’ characteristics are significantly associated with the attitudes toward OCD patients, such as the duration of practice as a psychiatrist, which is associated with the feeling of annoyance (χ2=16.657, df=6, P=0.011) and the perception that OCD patients have poor compliance with medications (χ2=15.568, df=6, P=0.016). The group of psychiatrists who have practiced for 6–10 years felt annoyed and perceived that OCD patients had poor compliance, in the highest number. The workplace also associated with the feeling of annoyance (χ2=12.764, df=6, P=0.047). Psychiatrists in general/provincial hospitals felt that OCD patients were annoying in the highest numbers, followed by psychiatrists in mental hospitals, while psychiatrists in medical university hospitals clearly least agreed with this attitude. The estimated number of outpatients psychiatrists treated in one period (approximately 3 hours) is related to feeling of admiration (χ2=17.401, df=9, P=0.043); the group that has less than ten patients most agreed that OCD patients were admirable. The estimated number of outpatients was also evidently associated with the perception that OCD patients have poor compliance with behavioral therapy (χ2=24.596, df=9, P=0.003), and the notion that OCD patients need more time when compared with other psychiatric disorder sufferers (χ2=24.788, df=9, P=0.003). The group who has more than 30 patients most agreed with both of attitudes.

Experiences with OCD patients

Regarding psychiatrists’ experience with OCD patients, the estimated number of OCD patients they had treated is associated with the perception that OCD patients have poor compliance with behavioral therapy (χ2=19.009, df=9, P=0.025). The group who has 11–20 patients least agreed with this attitude. The estimated time psychiatrists spent during the first visit with OCD patients is associated with feeling of pity (χ2=29.624, df=9, P=0.03). The group who spent less than 15 minutes with patients least agreed that these patients were pitiful, whereas psychiatrists who spent more than 45 minutes with them most agreed with this attitude. This characteristic is also related to the perception that OCD patients have poor compliance with behavioral therapy (χ2=19.531, df=9, P=0.021). All of the psychiatrists who spent less than 15 minutes with patients agreed with this attitude, while only 33.3% of those who spent more than 45 minutes agreed. The estimated time psychiatrists spent during the follow-up session with OCD patients is related to the perception that building a therapeutic relationship with OCD patients is more effortful than other psychiatric disorder sufferers (χ2=9.524, df=4, P=0.049). Those psychiatrists who spent more than 30 minutes most agreed with this attitude.

Experience and proficiency in ERP

Psychiatrists’ experience and proficiency in ERP is associated with feelings of admiration (χ2=18.279, df=9, P=0.032) and pity (χ2=34.144, df=9, P=0.001); 57.2% of psychiatrists who were proficient in ERP felt that OCD patients were admirable, while none of those who had never known ERP held this attitude. Likewise, all of ERP-proficient psychiatrists felt that these patients were pitiful, but only 50% of the group who had never known ERP felt in the same way. The proficiency in ERP also related to feeling of tiredness (χ2=17.591, df=9, P=0.04). Only 14.3% of ERP-proficient psychiatrists felt tired toward OCD patients, whereas 75% of those who had never known ERP felt tired. The other significant associations of this characteristic were the perception that OCD patients have poor compliance with medications (χ2=12.874, df=6, P=0.045). ERP-proficient psychiatrists most agreed with this attitude, while none of those who had never known about ERP agreed with it. This characteristic is also related to the perception that OCD patients need more time when compared with other psychiatric disorder sufferers (χ2=20.758, df=9, P=0.014). The psychiatrists who never practiced or had a lack of proficiency in ERP most agreed with this attitude, but none of ERP-proficient psychiatrists agreed with this attitude.

Psychiatrists’ confidence in treating OCD

Psychiatrists’ confidence in treating OCD patients is significantly associated with several items of specific attitudes. The number of confident psychiatrists (22.9%) felt tired toward OCD patients, which is much less than the psychiatrists without adequate confidence (66.7%) (χ2=16.41, df=3, P=0.001). A lower number of confident psychiatrists (12.9%) felt annoyed toward these patients than was the case for those who lacked confidence (19%) as well (P=0.015, FET). Most confident psychiatrists (72.9%) perceived that OCD patients were difficult to treat, while all of the psychiatrists who lacked confidence, held this attitude (χ2=8.129, df=3, P=0.043). In a similar way, only 8.5% of confident psychiatrists agreed with the statement that “I don’t want to treat OCD patients, when compared with other psychiatric disorder patients”, whereas 33.3% of those psychiatrists who lacked confidence agreed (χ2=13.698, df=3, P=0.003). Finally, only 4.3% of confident psychiatrists perceived that building therapeutic relationship with OCD patients is more difficult than with other psychiatric disorder patients (P=0.012, FET) compared with 19% of the psychiatrists who lacked confidence. Considering each treatment approach, the confidence in treating OCD with behavioral therapy is associated with several attitudes in a similar way with psychiatrists’ overall confidence, whereas the confidence in treating OCD with medications is significantly associated only with feelings of pity (χ2=10.541, df=3, P=0.032) and tiredness (χ2=8.384, df=3, P=0.039). Other attitudes that have significant associations with confidence in treating OCD with behavioral therapy were the perception that OCD patients have poor compliance with other psychotherapy (χ2=18.692, df=3, P=0.00) and the notion that OCD patients need more patience than other psychiatric disorder sufferers (χ2=10.369, df=3, P=0.016).

The psychiatrists’ sex, age, and their preferred treatment approach for OCD had no significant association with the attitudes toward OCD patients.

Discussion

This research aimed to study the psychiatrists’ attitudes toward OCD patients. It was found that more than 80% of the participating psychiatrists had positive feelings toward OCD patients, such as pity, understanding, and empathy. These results correlated with previous studies which found that psychiatrists tend to have a positive attitude toward mentally ill patients.4,10,11

Some of the psychiatrists in our focus group mentioned that OCD patients were admirable because they had been very patient and worked hard to alleviate their symptoms. However, the results found that only 18% of the participants agreed with this attitude. Therefore, the admiration may be a personal point of view, and not the common psychiatrists’ attitude toward OCD patients.

One of the more noteworthy findings was that about one-third of the psychiatrists perceived that OCD patients talked and asked too much, needed more time and patience compared with other psychiatric disorder sufferers, and they felt tired while treating these patients. Although not the majority of participating psychiatrists held these negative attitudes, there was still a significant number of negative attitudes, which might have a negative impact on their interaction with OCD patients including treatment process. Moreover, almost 80% of the psychiatrists thought that OCD patients were difficult to treat. It might resulted from the nature of OCD which has a chronic, waxing, and waning course and rarely shows complete recovery for its patients.

Regarding attitudes toward patients’ compliance to treatment, more than half of the psychiatrists perceived that OCD patients have poor compliance with behavioral therapy. As we found in our study, despite no statistically significant difference, 58.6% of psychiatrists who lack proficiency in ERP reported compliance problem with behavioral therapy, compared with 28.6% of ERP-proficient psychiatrists. The reason maybe because of the psychiatrists who lack proficiency in this kind of therapeutic method might not be able to adequately support the patients to cope with their difficulties, which in turn may lead to this attitude. On the contrary, only 7.7% of psychiatrists reported about the compliance problem with medications. There was no assessment of how they evaluate the patients’ compliance; as a result, it might not be possible to conclude that this attitude reflects the truth about OCD patients’ compliance.

It was found that some of psychiatrists’ characteristics were significantly associated with particular attitudes, such as the workplace. Those psychiatrists in general/provincial hospitals, together with psychiatrists in mental hospitals, felt that OCD patients were more annoying than the perception of psychiatrists in medical university hospitals. This finding might result from the matter of workload, which was greater in general, provincial, and mental hospitals than in medical university hospitals. The estimated number of outpatients psychiatrists treated in one period (approximately 3 hours) reflected in a similar way. The psychiatrists who have the fewest patients felt most admired, whereas the group who has greatest number of outpatients most agreed with the perception that (a) OCD patients have poor compliance with behavioral therapy, and (b) these patients need more time when compared with other psychiatric disorder sufferers. These findings might reflect that the psychiatrist’s burden of workload results in their negative attitudes. It correlates with previous study which found that high workload of health care organization lead to patient neglect.16

Regarding the psychiatrists’ experience with OCD patients, there were several significant associations with the attitudes. The estimated time psychiatrists spent during the first visit with OCD patients was associated with feeling of pity and the perception about compliance problem with behavioral therapy. The psychiatrists who spent longest time felt that these patients were pitiful and disagreed with the compliance problem more than those who spent less time. It can be hypothesized that the psychiatrists who spend more time with the patients might be able to deeply understand them that results in the positive attitude. Furthermore, they might create better therapeutic relationship and/or provide the patients behavioral therapy including psycho-education about etiology, course and treatment options for OCD, which leads to better compliance. However, we still need further investigation to prove whether psychiatrists who spend more time with OCD patients, especially on the first visit, will lead patients more easily to comply with behavioral therapy, and bring about better treatment outcomes.17–19

Psychiatrists’ experience and proficiency with ERP had significant associations with several items of attitudes. The psychiatrists who were proficient in ERP most agreed that OCD patients were admirable and pitiful. They also felt less tired and less agreed that these patients need more time than other psychiatric disorder sufferers than those who never practiced ERP or lack proficiency in this therapeutic intervention. These findings can be hypothesized that psychiatrist’s proficiency in ERP might lead to their positive attitudes toward OCD patients, which need to be further proved.

The confidence of psychiatrists in treating OCD with various methods was significantly associated with several kinds of attitudes. All of the associations manifested in agreement, psychiatrists who have confidence held more positive attitudes toward OCD patients than those who lack confidence. Specifically, the confidence in treating OCD with behavioral therapy has shown more association with attitudes than other type of treatment approaches. The more they are confident in behavioral therapy, the more positive attitudes they have. So it can be suggested that more training in behavioral therapy for OCD may be needed to help psychiatrists to be more confident, which might improve not only the attitudes toward these patients but also the treatment outcomes.

It was found that sex and age had no significant association with the attitudes toward OCD patients. This finding was correlated to a study by Addison and Thorpe,11 which found no difference about attitudes toward mentally ill patients between males and females. However, our finding differs from a study by Arvaniti et al10 which reported that women and the older people had held negative attitudes toward mental illness, such as social discrimination.

Limitations

There were some limitations to this study. Firstly, the sample was not a true representation of all Thai psychiatrists because there was no randomization in the sample selection, so we had more female and younger psychiatrists who participated. However, it was found that psychiatrists’ sex and age had no association with their attitudes toward OCD patients. Moreover, the distribution of their workplace was fairly consistent between the different types of hospitals, which is an important characteristic that might influence psychiatrists’ attitudes. Secondly, the questionnaire used to assess attitudes toward OCD patients has never been standardized and has not been previously studied in pilot study. However, we developed new questionnaire from the focus group interview, which provided deeper and more specific questions about attitudes toward OCD patients rather than those questions toward general mental illness as in some standardized questionnaires. Before distributing the questionnaire, it was reviewed by experts and peers. Thirdly, this study used questionnaire as a measure, so the results were subjective feelings of the psychiatrists, which might be different from the real situation. However, it still reflected the psychiatrists’ attitudes which usually have the impact on their patients. Finally, there were limited studies in the past we can compare to because most of them focus on attitudes toward general mental illness, not specific to OCD, and also used different methodologies and questionnaires.

Conclusion

Even though the participating psychiatrists clearly held positive attitudes toward OCD patients more than negative attitudes, most of them reported that OCD patients were difficult to treat. The psychiatrists who have fewer workload and who spent more time with OCD patients during the first visit seemed to hold more positive attitudes. Although three-fourth of the psychiatrists reported confidence in treating OCD patients, their confidence in treating with medications was higher than in the case of behavioral therapy and other psychotherapy. Their confidence in treatment especially their proficiency in ERP is significantly associated with more positive attitudes. Thus, it might be beneficial to improve the psychiatrists’ competence in treating OCD with behavioral therapy, which may lead to better attitudes toward patients and treatment outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first study about psychiatrists’ attitudes toward OCD patients; further studies are needed to affirm our results.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. We would like to thank Ms Pattaraporn Wisajun for her kind help in statistical methodology.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Solomon CG, Grant JE. Obsessive–compulsive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):646–653. | ||

Heyman I, Mataix-Cols D, Fineberg N. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. BMJ. 2006;333(7565):424–429. | ||

Rüsch N, Evans-Lacko SE, Henderson C, Flach C, Thornicroft G. Knowledge and attitudes as predictors of intentions to seek help for and disclose a mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(6):675–678. | ||

Gateshill G, Kucharska-Pietura K, Wattis J. Attitudes towards mental disorders and emotional empathy in mental health and other healthcare professionals. Psychiatrist. 2011;35(3):101–105. | ||

Schomerus G, Angermeyer MC. Stigma and its impact on help-seeking for mental disorders: what do we know? Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2008;17(01):31–37. | ||

Zartaloudi A, Madianos M. Stigma related to help-seeking from a mental health professional. Health Sci J. 2010;4(2):77–83. | ||

Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A. Discrimination in health care against people with mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):113–122. | ||

Thornicroft G, Rose D, Mehta N. Discrimination against people with mental illness: what can psychiatrists do? Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2010;16(1):53–59. | ||

Schulze B. Stigma and mental health professionals: a review of the evidence on an intricate relationship. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):137–155. | ||

Arvaniti A, Samakouri M, Kalamara E, Bochtsou V, Bikos C, Livaditis M. Health service staff’s attitudes towards patients with mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(8):658–665. | ||

Addison S, Thorpe S. Factors involved in the formation of attitudes towards those who are mentally ill. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(3):228–234. | ||

Nordt C, Rössler W, Lauber C. Attitudes of mental health professionals toward people with schizophrenia and major depression. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):709–714. | ||

Ucok A, Polat A, Sartorius N, Erkoc S, Atakli C. Attitudes of psychiatrists toward patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(1):89–91. | ||

Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Henderson S. Attitudes towards people with a mental disorder: a survey of the Australian public and health professionals. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33(1):77–83. | ||

Simonds LM, Thorpe SJ. Attitudes toward obsessive-compulsive disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(6):331–336. | ||

Reader TW, Gillespie A. Patient neglect in healthcare institutions: a systematic review and conceptual model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):156. | ||

Simpson HB, Maher MJ, Wang Y, Bao Y, Foa EB, Franklin M. Patient adherence predicts outcome from cognitive behavioral therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):247. | ||

De Araujo L, Ito L, Marks I. Early compliance and other factors predicting outcome of exposure for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(6):747–752. | ||

Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Zoellner LA, Dibernardo CL. Treatment compliance and outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Modif. 2002;26(4):447–463. |

Supplementary materials

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.