Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 12

Association between patients with dementia and high caregiving burden for caregivers from a medical center in Taiwan

Authors Yan GJ, Wang WF, Jhang KM, Lin CW, Wu HH

Received 15 September 2018

Accepted for publication 4 December 2018

Published 17 January 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 55—65

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S187676

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Guei-Jhen Yan,1 Wen-Fu Wang,2,3 Kai-Ming Jhang,4 Che-Wei Lin,5 Hsin-Hung Wu6,7

1Secretary Office, Chuanghua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan; 2Department of Neurology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan; 3Department of Holistic Wellness, Ming Dao University, Changhua, Taiwan; 4Department of Neurology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan; 5Medical Divisions of Performance Center, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan; 6Department of Business Administration, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, Taiwan; 7Department of M-Commerce and Multimedia Applications, Asia University, Taichung City, Taiwan

Background: Based on a person-centered care, the relationships between people with dementia and caregivers should be interconnected. There is a need to study what attributes would contribute a higher caregiving burden from a comprehensive viewpoint of care recipients and caregivers.

Methods: Apriori algorithm is performed with 12 variables for antecedents and caregiving burden for the consequent from the self-built database of a medical center in Taiwan. The minimum support, minimum confidence, and lift of Apriori algorithm are set to 5%, 90%, and > 1, respectively.

Results: Thirty-two rules that satisfy the threshold values are found. Our findings show that clinical dementia rating of care recipients, type of dementia of care recipients, and age of caregivers are not the attributing variables to affect the caregiving burden. In contrast, the highest burden results from a female spouse or a sole caregiver. Moreover, the burden is associated with the type of primary care, frequency of care, and help of key activities.

Keywords: Long-Term Care 2.0, help of key activities, type of primary care, frequency of care, association rule, person-centered care

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias have a significant influence on the people with the disease and their families.1 Caring for patients with dementia is a huge task, and many people feel strained. It is better to have a health and social system to provide a wide range of care and services to meet the needs of dementia patients and their families.1 The study conducted by Song and Oh2 pointed out that behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) is a source of psychological distress for caregivers, and the cumulative scores of BPSD are correlated positively with the total distress scores for formal caregivers (registered nurses and care workers) of nursing homes in South Korea.

BPSD such as wandering, resistance to care, agitation, and aggression increase the workloads for caregivers and complications for patients in long-term care facilities in Japan.3 In addition, BPSD might cause difficulties for caregivers to care patients with dementia, and these difficulties may lead to elder abuses and an increased use of physical restraints.3 Thus, a palliative approach that involves the families and healthcare staff is recommended to provide caregiving to people with dementia.4 That is, caregivers including care staff and families must have enough knowledge of dementia in order to offer appropriate ongoing care. Therefore, knowledge about the association between specific characteristics of caregivers and caregivers’ burden is essential.2

In practice, caregivers include informal and formal caregivers. Informal caregivers are unpaid individuals such as a spouse, partner, family member, friend, or neighbor involved in assisting patients with dementia with activities of daily living and/or medical tasks. On the other hand, formal caregivers are paid care providers, who provide care in one’s home or in a care setting such as day cares, residential facilities, or long-term care facilities. In Taiwan, patients with dementia rely heavily on help from their families.5 In this study, caregivers include both informal and formal caregivers because the self-built database from a medical center in Taiwan does not specify the type of caregivers in detail.

Conde-Sala et al,6 Braun et al,7 and Nagatomo et al8 reported that people with dementia with one or two (demographic) variables might contribute to a higher caregiving burden. For instance, spouses feel highly stressful than children in caregiving. The caregiving burden of male recipients is higher than that of female recipients. However, most of the studies did not specify the level of caregiving burden in terms of some burden scales. Moreover, rare studies have been found to provide a more comprehensive viewpoint by combining various (demographic) variables to identify what attributes could possibly result in a higher caregiving burden. That is, the associations of caregivers and care recipients are very complicated and have not been discussed thoroughly. Particularly, the contributing variables that cause care providers the highest level of caregiving burden are required to be studied in order to release caregivers’ stress and provide better care for patients with dementia.

Clissett et al9 and Brooker and Latham10 stated that an ideal approach of caring for people with dementia in a long-term care is to use a person-centered care. Obviously, the relationships between people with dementia and caregivers should be interconnected in order to provide a person-centered care. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify what attributes could result in the severe caregiving burden from a comprehensive viewpoint of both dementia patients and caregivers. Association rules particularly Apriori algorithm can be performed to uncover interesting statistical correlations from a multidimensional viewpoint when each attribute is considered as a dimension by satisfying both minimum support and confidence threshold values.11 In doing so, when a caregiver with a high caregiving burden is identified, helps from hospitals, social workers, or governments can be provided to relieve his/her burden based on a person-centered care.

Materials and methods

This study uses a self-built database with a total of 262 registered patients with dementia from a medical center in Taiwan from October 2015 to June 2017. The clinical trial approval certificate was approved by the institutional review board of Changhua Christian Hospital in Changhua County, Taiwan, with protocol number of CCH IRB 160165. Regarding the clinical trial approval, patient informed consent was not required for the data, as the data were anonymized. In the early stage of data collection and database establishment, the variables for each patient with dementia are limited. Each record from a patient with dementia includes clinical dementia rating (CDR) of the care recipient, age of the caregiver, care recipient relation (who are you caring?), type of primary care, frequency of care, help of key activities (multiple choice: 1 if help of a key activity is applied; 0 if not), the caregiving burden (0–13: little or no burden; 14–25: moderate burden; and 26–42: severe burden), type of dementia, gender of the care recipient, age of the care recipient, and help with activities of daily living. If any data set has missing information from one or more columns, then that data set is considered as an incomplete data set. Hence, in this study 169 incomplete data sets were removed and 93 patients with dementia were used for further analyses. The detailed variable information about 93 data sets is provided in Table 1.

| Table 1 Variable information of patients with dementia Abbreviation: CDR, clinical dementia rating. |

A majority of dementia patients are women (64.5%) with Alzheimer’s disease (57%) whose ages are ≥75 years (86%) and have mild dementia (57%). On the other hand, the majority of caregivers are recipients’ children (55.9%) aged ≥50 years (83.9%) with 6 days or more per week in frequency (92.5%) by either sole (46.3%) or shared (37.6%) caregiving in primary care. The burden of caregivers is moderate (68.8%). In addition, key activities for the care recipients are accompany (88.2%), physical condition and/or activities of daily living (84.9%), and navigating in and through the healthcare system or rehabilitation (81.7%).

The caregiving burden is assessed by self-test of memory clinic caregiver’s stress issued by Taiwan Association of Family Caregivers with 14 questions as shown in Table 2. Each caregiver is asked to reply each question by one of the four selections, including never with a value of zero, rarely with a value of 1, sometimes with a value of 2, and quite frequently with a value of 3. The level of caregiving burden is obtained by aggregating the total scores from these 14 questions. Therefore, the caregiving burden of each caregiver based on the total score can be classified into three levels, ie, 0–13 (little or no burden), 14–15 (moderate burden), and 26–42 (severe burden).

| Table 2 Self-test of memory clinic caregiver’s stress |

The purpose of this study is to identify the associations among care recipients, caregivers, and the caregiving burden. That is, the study intends to find what attributes (scenarios) would result in a severe level of caregiving burden for each caregiver. Association rules enable users or domain experts to find interesting statistical correlations from a multidimensional viewpoint when an attribute is viewed as a dimension.11 Besides, association rules are an approach to investigate the dependence among attributes (variables) by a type of conditional probabilities, which is similar to Bayesian networks.12 Specifically, association rules use the form “If antecedent, then consequent” to generate rules.12 In this study, Apriori algorithm, which is very useful to discover interesting relationships previously unknown in the data sets, is used to find rules and associations that exist between any of the attributes by setting up support, confidence, and lift.11–16 Rules generated by the Apriori algorithm need to satisfy both minimum support and confidence threshold values.11,12

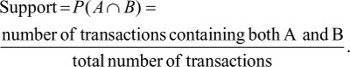

The definitions of support, confidence, and lift are depicted subsequently.11,12,16 The support for an association rule A ⇒ B is the percentage of transactions in the database containing both A and B:

| (1) |

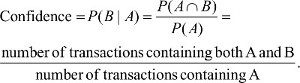

The confidence of the association rule A ⇒ B is to evaluate the accuracy of the rule in accordance with the percentage of transactions in the database containing A and also B simultaneously:

| (2) |

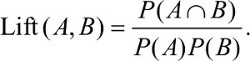

Lift is a simple correlation that measures if A and B are independent or dependent and correlated events:

| (3) |

Han and Kamber11 described that the probability of A and B is independent if a particular rule has a lift of one. If two events are independent, no rule will be drawn containing these two events. On the contrary, if a rule has a lift greater than one, A and B are dependent and positively correlated. In practice, Larose12 stated that analysts might prefer rules with either a high support or a high confidence and usually both. The purpose of association rules is to find strong rules that meet or surpass certain minimum support and confidence criteria.

Before performing the Apriori algorithm by IBM SPSS Modeler 14.1, the notations defined by numerical values are described in Table 1, where data type defines each type of variables of dementia patients. The input variables for antecedents include CDR of the care recipient, age of the caregiver, care recipient relation, type of primary care, frequency of care, help of key activities, type of dementia, gender of the care recipient, age of the care recipient, and help with activities of daily living. It is worth to note that there are three activities in help of key activities. If a caregiver applies a particular key activity, a value of one is assigned. If not, a value of zero is assigned. Therefore, 12 variables belong to antecedents. On the other hand, the input variable for the consequent is the caregiving burden. The minimum support, minimum confidence, and lift are set to 5%, 90%, and >1, respectively.

Results

The purpose of this study is to find associations between antecedents and the consequent by identifying what attributes that could cause the highest burden for caregivers based on the self-built database from a medical center in Taiwan. Table 3 summarizes 32 rules when caregivers have a severe burden. In Table 3, consequent is the severe burden for caregivers. In order to reduce the complexity of the table, this column is removed. On the other hand, antecedents represent “the reasons” to result in the severe caregiving burden. That is, antecedents that appeared in rules are considered to be critical variables. Furthermore, if there are two or more antecedents in a rule, these antecedents should be incurred simultaneously. For instance, Rule 1 indicates that a female spouse, who navigates in and through the healthcare system or rehabilitation for a male recipient with the age of 75–79 years, has a severe caregiving burden.

| Table 3 Results generated by Apriori algorithm when the caregiving burden is severe |

There are 32 rules generated by the Apriori algorithm performed by IBM SPSS Modeler 14.1. The first 28 rules can be generalized into one rule, whereas the rest of four rules can be generalized into the other rule. That is, caregivers feel a severe burden when the patient is male, aged 75–79 years with the help of key activities in navigating in and through the healthcare system or rehabilitation. The more detailed variables included are care recipient relation (spouse), type of primary care (sole caregiver), help with activities of daily living (no), frequency of care (6 days or more per week), help of key activities (accompany), or a combination of two or more variables. The second generalized rule is as follows: The caregivers feel a severe burden when the dementia patients are male with care recipient relation (spouse) and do not need any help with activities of daily living but need help in key activities in navigating in and through the healthcare system or rehabilitation. The differences among these four rules specifically include help of key activities (physical condition and/or activities of daily living), type of primary care (sole caregiver), help of key activities (accompany), or frequency of care (6 days or more per week).

Discussion

Conde-Sala et al6 concluded that some studies reported that adult children had the highest level of the caregiving burden, but others showed that spousal caregivers had the greatest burden. This study shows that female spouses have higher burden that is consistent with the study conducted by Braun et al,7 showing that spousal caregiving is highly stressful. The findings of this study are consistent with those of Nagatomo et al8 that spouses have a higher burden value than children in caregiving. On the other hand, Nagatomo et al8 found that the caregiving burden of male care recipients is significantly higher than that of females. Besides, the caregiving burden of an elder female who solely provides caregiving to her husband is higher.17 Our results are consistent with those of Nagatomo et al8 and Brown.17

Song and Oh2 pointed out that the more severe the symptoms of patients with dementia, the more distress was experienced by caregivers. However, this study does not draw similar conclusions. In fact, CDR of the care recipient, type of dementia of the care recipient, and age of the caregiver are not the major variables to influence the caregiving burden. In contrast, the burden of a female spouse or a sole caregiver is higher. Besides, the burden is associated with type of primary care, frequency of care, and help of key activities.

Previous studies only showed one or two variables that might cause higher caregiving burden. That is, each variable is treated as an independent variable. Besides, no specified caregiving burden is given, ie, the level of caregiving burden. On the contrary, this study provides a more comprehensive viewpoint by combining various variables to identify what attributes might result in the highest caregiving burden for care providers. For instance, a male dementia patient with the age of 75–79 years solely cared by his wife results in the highest caregiving burden. A male patient with dementia cared by his wife who does not need help with activities of daily living but needs navigating in and through the healthcare system or rehabilitation would result in the highest caregiving burden. Our results can be viewed as a part of person-centered care that has the interconnected relationships between people with dementia and caregivers.9,10 This study provides more specific guidelines for caregivers who are going to experience the highest caregiving burden if a scenario meets one of the 32 rules listed in Table 3. When a pair of a care recipient and a caregiver matches one of the rules, it is advised that this caregiver needs more help from hospitals, social workers, or governments to relieve his/her burden in accordance with a person-centered care.

In 2013, the government of Taiwan (Ministry of Health and Welfare) launched the “long-term care service network” to develop a dementia multicare service network and to establish dementia care resources including “school of wisdom,” dementia daycare services, family care providers support service network, and dementia special care units.18 A report from Central News Agency in August 201719 summarized that the Ministry of Health and Welfare aims to increase the number of dementia care centers and the diagnosis rates over the next 4 years as well as to help at least 5% of the 18 million people in the age range from 15 to 64 years in Taiwan to gain a deeper understanding of the dementia over the next 4 years.

Launched in November 2016, “Long-Term Care 2.0 in Taiwan” developed by the Ministry of Health and Welfare gets started to respond to an aging society.20 The missions include person-centered, community-based, and continuum of care. The goals are to establish an accessible, affordable, universal long-term care service system with good quality and have a downstream preparedness to provide discharge plan and home-based medical care. Patients with dementia aged ≥50 years are also included in “Long-Term Care 2.0 in Taiwan.” That is, the long-term dementia care in Taiwan is in a start-up stage, and there is a lack of qualified caregivers in this program.20 Moreover, Taiwan’s long-term care program should focus on boosting the quality of life for both patients and caregivers.20 In fact, this medical center establishes a dementia center and is in charge of diagnoses of patients with dementia and provisions of dementia care in Changhua County, Taiwan, requested by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. However, there is a need to provide (additional) knowledge for dementia care from care recipients and care providers in a long-term perspective. This study fills the gap and provides how a person-centered care in “Long-Term Care 2.0 in Taiwan” can be fulfilled.

Conclusion

Clissett et al9 and Brooker and Latham10 concluded that a person-centered care is an ideal approach to care for people with dementia in a long-term care. Besides, it is essentially important to find the interconnected relationships between dementia patients and caregivers. This study uses the Apriori algorithm to find associations between dementia patients and caregivers from a more comprehensive viewpoint by combining various variables to identify what attributes might result in the highest caregiving burden for caregivers. Variables including CDR of the care recipient, type of dementia of the care recipient, and age of the caregiver are not the contributing factors to influence the caregiving burden. This study shows that the highest caregiving burden is associated with type of primary care, frequency of care, and help of key activities when the patient with dementia is male cared by the spouse or solely.

Author contributions

Guei-Jhen Yan wrote literature reviews and results, analyzed the data, and provided the results. Wen-Fu Wang and Kai-Ming Jhang provided the information about dementia and interpreted the data. Che-Wei Lin wrote partial literature review and revised the manuscript. Hsin-Hung Wu proposed the concept and design, revised the manuscript, and discussed the results with the other authors. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Wortmann M. Dementia: a global health priority – highlights from an ADI and World Health Organization report. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012;4(5):40. | ||

Song JA, Oh Y. The association between the burden on formal caregivers and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in Korean elderly in nursing homes. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(5):346–354. | ||

Kutsumi M, Ito M, Sugiura K, Terabe M, Mikami H. Management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in long-term care facilities in Japan. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9(4):186–195. | ||

Robinson A, Eccleston C, Annear M, et al. Who knows, who cares? Dementia knowledge among nurses, care workers, and family members of people living with dementia. J Palliat Care. 2014;30(3):158–165. | ||

Lin LN, Wu SC. Measurement structure of the caregiver burden scale: findings from a national community survey in Taiwan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(1):176–184. | ||

Conde-Sala JL, Garre-Olmo J, Turró-Garriga O, Vilalta-Franch J, López-Pousa S. Differential features of burden between spouse and adult-child caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: an exploratory comparative design. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(10):1262–1273. | ||

Braun M, Scholz U, Bailey B, Perren S, Hornung R, Martin M. Dementia caregiving in spousal relationships: a dyadic perspective. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(3):426–436. | ||

Nagatomo I, Akasaki Y, Uchida M, Tominaga M, Hashiguchi W, Takigawa M. Gender of demented patients and specific family relationship of caregiver to patients influence mental fatigue and burdens on relatives as caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(8):618–625. | ||

Clissett P, Porock D, Harwood RH, Gladman JR. The challenges of achieving person-centred care in acute hospitals: a qualitative study of people with dementia and their families. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(11):1495–1503. | ||

Brooker D, Latham I. Person-Centred Dementia Care: Making Services Better with the VIPS Framework. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2016. | ||

Han J, Kamber M. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques. 2nd ed. New York: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers; 2006. | ||

Larose DT. Discovering Knowledge in Data: An Introduction to Data Mining. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. | ||

IBM Corporation, IBM SPSS modeler 15 modeling nodes, IBM Corporation. 2012. Available from: ftp://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/documentation/modeler/15.0/en/ModelingNodes.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2018 | ||

Nahar J, Imam T, Tickle KS, Chen Y-PP. Association rule mining to detect factors which contribute to heart disease in males and females. Expert Syst Appl. 2013;40(4):1086–1093. | ||

Kaur M, Kang S. Market basket analysis: identify the changing trends of market data using association rule mining. Procedia Comput Sci. 2016;85:78–85. | ||

Lee YC, Huang CH, Lin YC, Wu HH. Association rule mining to Identify critical demographic variables influencing the degree of burnout in a regional teaching hospital. TEM J. 2017;6(3):497–502. | ||

Brown PL. The burden of caring for a husband with Alzheimer disease. Home Health Nurse. 1991;9(3):33–38. | ||

Ministry of Health and Welfare. Taiwan Dementia Policy: A Framework for Prevention and Care. Taipei: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2014. | ||

Central News Agency. Taiwan’s Government aims to Increase Dementia Care Centers, Diagnosis Rates[2017.08.26]. Available form: https://www.taiwan-healthcare.org/medic-all/medical-advances?articleSysid=MtsArticle20170829170414210543490&articleTypeSysid=A. Accessed November 12, 2018. | ||

TheNewsLens [homepage on the Internet]. Taiwan primes for old age apocalypse with long-term care plan, Taiwan Business TOPICS Magazine, October 16, 2018. Available from: https://international.thenewslens.com/article/106124. Accessed December 28, 2018. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.