Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 13

Assessment of Organizational Commitment Among Nurses in a Major Public Hospital in Saudi Arabia

Authors Al-Haroon HI , Al-Qahtani MF

Received 4 April 2020

Accepted for publication 3 June 2020

Published 16 June 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 519—526

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S256856

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Hind Ibraheem Al-Haroon, 1 Mona Faisal Al-Qahtani 2

1Department of Internal Medicine, Dammam Medical Complex, Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Public Health, College of Public Health, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Mona Faisal Al-Qahtani

Department of Public Health, College of Public Health, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, PO Box 2435, Dammam 31441, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Tel +966 50 498 1410

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Nurses play a vital role in the provision of healthcare internationally. The level of organizational commitment of healthcare workers, including nurses, is closely connected to the productivity and quality of care provided by healthcare institutions. The aims of the present study were to explore nurses’ levels of organizational commitment and the impact of key sociodemographic variables on this issue.

Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive quantitative study was conducted at a major public hospital in Saudi Arabia during April and May 2019. A revised validated version of the three-component model (TCM) questionnaire was self-administered to a systematic random sample of 384 nurses. The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Mean scores were compared by independent variables using an independent sample t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). Multiple linear regression analysis was performed.

Results: Out of 384 participants, 337 responded, yielding a response rate of 88%. Overall, 47.88% of the nurses agreed with all items related to the organizational commitment scale, while only 22.3% disagreed. There was a significant difference in the levels of commitment among nurses in the various age groups (p = 0.024). The continuous commitment subscale received the largest number of positive responses.

Conclusion: Most nurses showed a moderate level of job commitment. Greater organizational commitment was positively related to sociodemographic variables, such as age and nationality, and the only positive predictor of overall organizational commitment was age. Nursing policy makers should enhance the organizational commitment of nurses by developing strategies to recruit, attract, and retain committed nurses.

Keywords: healthcare, nurses, organizational commitment, Saudi Arabia

A Letter to the Editor has been published for this article.

Introduction

Organizational commitment has been well documented in the management and organizational behavior literature over the last five decades. In addition, human resources has been shown to be the most important source of competitive advantage.

Mowday et al,1 defined organizational commitment as “the relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization”. Belief in organizational values and aims, loyalty towards an organization, moral commitment and the desire to remain in an organization constitute organizational commitment.2,3 It is also the extent to which workers associate with their organization and its goals.4 Hosseini and Talebiannia5 noted that organizational commitment is the tendency of social actors to allocate their authority and loyalty to social systems. However, organizational commitment is customarily characterized as

A strong belief in and acceptance of the organization’s goals and values, a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization and a definite desire to maintain organizational membership.6

Elsewhere, organizational commitment7 has been characterized as the degree to which a worker feels that he or she belongs to an institution and believes that the institution is related to his or her life.

The most famous and generally utilized classification of commitment was advanced by Allen and Meyer,8 who proposed three components: affective, normative and continuance commitment. Affective commitment is the passionate connection of workers to their association, their desire to see the organization excel in its objectives and the pride they take in being a part of that association. Normative commitment involves employees’ ethical commitments towards the association since participation is seen as “the correct thing to do”. Continuance commitment involves a person’s apparent need to stay with an association because leaving the association would be expensive.

Organizational commitment in the nursing sector has been studied globally since its inception in the 1970s. The nursing profession is a vital pillar of society, and healthcare delivery and health standards rely heavily on nursing staff. The wellbeing of this important societal sector is directly related to nurses’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction, which, in turn, are essential for patient safety.9 Healthcare organizations are in dire need of a culture in which the nursing employees are dedicated, motivated and strongly associated with their sacred profession. Nurses’ perceptions of the general approach to organizational commitment is an important factor in understanding organizational behavior and a good predictor of employee retention, job satisfaction and job performance.10,11 Increasing organizational commitment and job satisfaction are imperative in order to better maintain nursing staff.12

The Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia has highlighted the significant nursing shortage in the Saudi labor force.13 Nurses represents 50% of the health workforce but provide the majority of the health services.14 This may have deleterious or beneficial effects on the health sector in general. Nurses are the cornerstone of the healthcare system and must be provided with the best conditions to enable them to perform their duties in the best possible way. Optimal nursing performance depends upon the knowledge, competencies, job satisfaction and organizational commitment of individual nurses.10 Nurses must be happy with their employers in order to maintain and achieve the desired healthcare services and standards. As such, managers ought to provide nurses with good working conditions that bolster their organizational commitment and job satisfaction and ultimately result in improved effectiveness and performance.9

There is a significant gap in the literature regarding organizational commitment and the nursing sector in this region. The success of healthcare organizations depends on numerous significant components; nurses’ commitment to their organization is an essential component, which aids the organization in accomplishing its goals, promotes organizational efficiency and effectiveness and improves the quality of healthcare services.

Therefore, the main objectives of the current study were to explore nurses’ levels of organizational commitment and the impact of demographic factors on organizational commitment among nurses working in the public health sector, particularly in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. It is hoped that the results of this study will add to the knowledge base on this issue, help policy makers develop feasible long-term strategies to retain nurses, improve their performance and develop organizational policies that improve of nurses’ commitment.

Materials and Methods

Design

A cross-sectional descriptive quantitative study design using a systematic random sampling was employed to collect the research data.

Setting and Sample

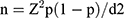

This study was conducted at a major public hospital with a 400-bed capacity in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia, during April and May 2019. The hospital was comprised of all adult medical and surgical specialties and had five specialized centers: the Tuberculosis Center; Nephrology, Cardiology and Surgery Center; the Center for Diabetes, Ophthalmology and Endocrinology; and the Dental and Physiotherapy Center. A systematic random sampling technique was utilized to select nurses. To determine the sample size, Daniel’s15 sample size formula was used:

where Z = a confidence level (CI) of 95%, Z = 1.96, p = expected proportion and is considered 0.5, d = precision and is considered 0.05 (indicating good precision and small error of estimate). It was estimated that 50% of the nurses had a satisfactory level of commitment in their present working climate at a 5% level of precision and a 5% level of significance; therefore, a sample of 384 nurses was needed.

The sampling interval was calculated by dividing the total number of registered nurses in the target hospital (1211) by the target sample size (384), which resulted in 3.15. Then, a number between one and three was selected from the random number table (in this case, two) for the first nurse. Every third nurse from the human resources’ nursing manpower database was selected. The inclusion criteria were English-speaking full-time registered nurses working in the target hospital with more than one year of experience. The exclusion criteria were nurses with a duration of service of less than one year and those who were unwilling to participate in the current study.

Instrument

The instrument used in the present study was a paper-based self-completion survey, which consisted of two sections. Section 1 focused on the demographic characteristics of the participants: sex, marital status, nationality, level of education, age, range of salary and years of nursing experience. Section 2 addressed organizational commitment, which was measured using the revised version of the three-component model (TCM) questionnaire created by Meyer et al.8 This validated and reliable8,16 instrument is comprised of 18 items and measures affective, normative and continuance commitment. A Likert-type scale (5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree) was used for each item. A pilot study was performed to explore the feasibility and applicability of TCM. Twenty registered nurses from another Eastern Province public hospital took the 10–15-minute survey. The results appeared that the TCM was clear, and there was no ambiguous wording. The pilot study respondents’ data was not included in the main study results.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval of the study was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) (PGS‐2019‐03‐ 233) of Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (IAU) in Saudi Arabia. Informed consent was given from all participants of this study. All the participating nurses were briefed about the study objectives.

Data Collection

The data collector distributed the paper-based questionnaires to the participating nurses in all of the hospital departments. All responses were submitted anonymously to the data collector.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Frequency distribution and summary statistics were analyzed by descriptive analysis. An independent sample t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were utilized to compare the means of the respondents’ demographic variables. Regression analysis was utilized to explore the predictor variables related to organizational commitment. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The mean overall organizational commitment scores were classified as very low (if < 2), low (if between 2.00 and 2.99), moderate (if between 3 and 3.99) or high (if > 4).

Results

Out of 384 participants, 337 responded, yielding a response rate of 88%.

Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 depicts the respondents’ demographic characteristics. Females constituted 87% of the respondent group, while 13.4% were male. The majority (61.4%) of the participants were 30–40 years old, 31.5% were 20–30 years old and only 7.1% were older than 40 years of age. Nearly two-thirds of the participants were married, and 85% of the participants were Saudi. Sixty-eight percent of the respondents had a nursing diploma, nearly one-third had a bachelor’s degree and only 0.9% had a master’s degree. Fifty-eight percent had a monthly salary of more than 10,000 SR, 38% had a salary of 5000–10,000 SR and only 3.9% had a salary range of 2500–5000 SR. Half of the respondents had 5–10 years of work experience, while 23% had 10–15 years of experience.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of the Participants’ Demographic Characteristics (n = 337) |

The consistency of the questionnaire was determined using alpha coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha for reliability analysis) (Table 2). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the organizational commitment scale and its three subscales ranged from.881 to.756. As these coefficients were greater than 0.70, it could be considered reliable17 for this study.

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Reliability Coefficient of the Organizational Commitment Scales and Its Subscales |

Tables 3 and 4 report the findings of the independent samples t-test and ANOVA, which were performed to explore how demographic differences affect organizational commitment. For overall organizational commitment, there was a significant difference between Saudi and non-Saudi nurses (p = 0.013). Non-Saudi nurses showed a higher mean than Saudi nurses (3.50 and 3.29, respectively). There was also a significant difference between the nurses based on their age (p = 0.024); older nurses (>40 years) showed a higher mean than the nurses in other age groups.

|

Table 3 T-test for Demographic Differences in Nurses’ Overall Organizational Commitments |

|

Table 4 ANOVA Results for Demographic Differences in Nurses’ Overall Organizational Commitments |

Table 5 shows the frequency distributions of the nurses’ organizational commitment levels. The five points of the TCM were recoded to a three-point scale, where strongly agree was recoded as agree and strongly disagree was recoded as disagree.

|

Table 5 Frequency Distribution of Nurses’ Organizational Commitment (n = 337) |

Regression Analysis: Overall Organizational Commitment

A simple linear regression was calculated to predict overall organizational commitment based on the participants’ sex, age, marital status, nationality, educational level, monthly salary and years of nursing experience (Table 6). The findings indicated that participant sex, marital status, nationality, educational level, monthly salary and years of nursing experience were not significant predictors of overall organizational commitment (p > 0.05).

|

Table 6 Regression Analysis of Overall Organizational Commitment |

Only age was a significant predictor of organizational commitment (age: β = 0.131, t = 2.073, p = 0.039). A significant regression equation was found (F = 2.470, p < 0.05) with an R2 of 0.050, indicating that only 5% of the variance in the level of overall organizational commitment was explained by age, where 95% of the variance might be explained by other factors.

Discussion

This study measured the levels of organizational commitment and the impact of key demographic variables among the nursing staff of the main public hospital in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. The study showed that 47.88% of the nurses agreed with all of the organizational commitment scale items, while only 22.3% disagreed. It also revealed that the nurses had a moderate overall organizational commitment level, which is consistent with the literature.9,18,19 In the current study, the nurses demonstrated more agreement with the continuous commitment subscale than the normative and affective commitment subscales. Our results are in line with Saleh et al’s18 findings, which showed that nurses had a higher mean score for continuous commitment than affective and normative commitment.

For overall organizational commitment, there was a significant difference in the levels of commitment among the nurses in the various age groups (p = 0.024). The youngest nurses (20–30 years old) were the least committed ones. Older people (> 40 years old) appeared to be more committed to the organization. This result might be explained by the level of enthusiasm of older people, which is expected to be lower than that of younger people, who often hunt for new job perspectives and find it easy to switch jobs and relocate. Age and experience are highly related to organizational commitment and job satisfaction. For example, in one study, experienced medical attendants were happier and more dedicated to their profession than youthful and novice ones.20 Therefore, it is recommended that organizational decision makers place more emphasis on retaining older employees because they are more committed to their jobs than younger employees. These significant generational/age group differences in nurses’ level of commitment might present some challenges for human resources experts when investigating how to manage and work with nurses from various age groups.21

Saudi nurses were less committed to their jobs than non-Saudi nurses. Saudi Arabia depends heavily on non-Saudi expertise, especially in the healthcare sector, which has a high turnover rate that generates workforce instability.22 Given this situation, as well as the national nursing shortage and problems attracting and retaining Saudi nationals in the nursing workforce,23 nursing workplace enhancements are recommended to try to attract more Saudi female nurses to the profession and increase their feelings of belonging, which might positively affect their levels of satisfaction with and commitment to their organization. There were no significant differences based on the nurses’ education, monthly salary and experience levels.

Regarding statements of affective commitment, Table 5 shows that the majority of the respondents agreed with the following items: “I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own” and “I do not feel ‘emotionally attached’ to this organization” (55.5% and 54.6%, respectively). However, the most commonly disagreed with statements were “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization” and “This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me” (30.9% and 24.9%, respectively). Employees with a high level of affective commitment will enthusiastically continue working for their organization since they feel connected to it and are in full harmony with its internal values and standards.24 Therefore, it is important to encourage work fulfilment and reduce effort-reward imbalances by providing adequate staffing and easy access to support in order to increase nurses’ organizational commitment.12

Regarding statements of continuous commitment, Table 5 shows that the majority of respondents agreed with the following items: “Right now, staying with my organization is a matter of necessity as much as desire”, “It would be very hard for me to leave my organization right now, even if I wanted to do that” and “Too much of my life would be disrupted if I decided I wanted to leave my organization now” (62.6%, 62.3% and 59.1%, respectively). However, the most commonly disagreed with statements were: “One of the few negative consequences of leaving this organization would be the scarcity of available alternatives” and “If I had not already put so much of myself into this organization, I might consider working elsewhere” (25.5% and 22.3%, respectively). Thus, work inspiration, organizational culture and work environment (authoritative responsibility) have positive and noteworthy effects on performance by increasing organizational commitment and job satisfaction.25,26

Regarding statements of normative commitment, Table 5 shows that more than half of the nurses agreed with the statement, “I do not feel any obligation to remain with my current employer” (55.2%). The largest percentages of nurses disagreed with the following statements: “I owe a great deal to my organization” and “I would feel guilty if I left my organization now” (29.4% and 27%, respectively). An Egyptian study27 documented a significant positive correlation between nurses’ overall perception of their profession and overall commitment to a nursing career. Therefore, public awareness campaigns portraying a positive image of nursing careers could help improve nursing career commitment. In addition, a positive connection between authoritative responsibility and nursing conduct and behavior has been established.28 The findings of the regression analysis revealed that age was the only demographic factor that affected the level of organizational commitment, which was also reported by Eleswed and Mohammed.20 However, our results contradict those of Timalsina et al,29 who found that educational level was one of the factors that predicted organizational commitment. The identification of a relationship between organizational commitment and age in our study also contradicts the findings of Arbabisarjou et al.19 However, the absence of significant relationships between organizational commitment and factors, such as gender, educational level and working experience were in line with the results of Arbabisarjou et al.19

Although this cross-sectional study adds to the research on organizational commitment in this region, it does have some limitations. First, since this study was restricted to nurses from a single public hospital, the results should be generalized with caution. Future studies should examine other public and private hospitals to more broadly explore nurses’ job commitment levels in various medical institutions. Second, the data collection method was a self-administered questionnaire, which made under-reporting and over-reporting possible. Future studies should use different data collection approaches, such as interviews. Third, Future studies should focus on other factors that might impact the level of commitment of nurses in other national contexts and organizational environments.

Conclusions

Our research confirms that organizational commitment is positively related to older age and non-Saudi nationality. The continuous commitment subscale received the largest number of positive responses followed by the normative commitment and affective commitment subscales. Overall, the healthcare sector needs to implement reforms and inculcate an organizational culture where younger and newly recruited staff feel ownership of their profession and are intimately involved with their organization’s vision and mission. To help accomplish this and improve medical services, the human resources department should overhaul their working terms and conditions. Additionally, the findings of this study will help policy makers improve retention strategies and enhance the practice environments and job-related outcomes in the nursing sector in Saudi Arabia. Moreover, an important implication of the present study is that policy makers should consider enhancing the organizational commitment of nurses to be an organizational issue that requires the development of strategies to recruit, attract and retain committed nurses.

Ethics Approval

Approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University in Saudi Arabia was obtained for the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to all nurses for their valuable participation in the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Mowday RT, Porter LW, Steers RM. Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover. New York: Academic Press; 2013.

2. Colquitt JA, LePine JA, Wesson MJ. Organizational Behavior: Improving Performance and Commitment in the Workplace.

3. Alrowwad A, Almajali D, Masa’deh R, Obeidat B, Aqqad N The role of organizational commitment in enhancing organizational effectiveness. Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020; 2019. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332697163_The_Role_of_Organizational_Commitment_in_Enhancing_Organizational_Effectiveness.

4. Dinc MS. Organizational Behavior in Higher Education. Balti: Lap Lambert Academic Publishing; 2017.

5. Hosseini M, Talebiannia H. Correlation between organizational commitment and organizational climate of physical education teachers of schools of Zanjan. Int J Sport Stud. 2015;5(2):181–185.

6. Watson J, Pape L, Murin A, Gemin B, Vashaw L. Keeping Pace with K-12 Digital Learning: An Annual Review of Policy and Practice. United State: Evergreen Education Group; 2014.

7. Meyer JP, Kam C, Goldenberg I, Bremner NL. Organizational commitment in the military: application of a profile approach. Mil Psychol. 2013;25(4):381–401. doi:10.1037/mil0000007

8. Meyer JP, Allen NJ. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application. California: Sage; 1997.

9. Salem OA, Baddar F, AL-Mugatti HM. Relationship between nurses job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J Nur Health Sci. 2016;5(1):49–55.

10. Dinc M, Kuzey C, Steta N. Nurses’ job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between organizational commitment components and job performance. J Workplace Behav Health. 2018;33(2):1–21. doi:10.1080/15555240.2018.1464930

11. Hakami A, Almutairi H, AlOtaibi R, AlOtaibi T, Al Battal A. The relationship between nurses job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Health Sci J. 2020;14(1):692.

12. Satoh M, Watanabe I, Asakura K. Occupational commitment and job satisfaction mediate effort–reward imbalance and the intention to continue nursing. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2017a;14(1):49–60. doi:10.1111/jjns.12135

13. Lamadah SM, Sayed HY. Challenges facing nursing profession in Saudi Arabia. J Biol Agric Healthcare. 2014;4(7):20–25.

14. Majeed F. Effectiveness of case-based teaching of physiology for nursing students. J Taibah Univ Medical Sci. 2014;9(4):289–292. doi:10.1016/j.jtumed.2013.12.005

15. Daniel WW, Cross CL. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences.

16. Wilson M, Bakkabulindi F, Ssempebwa J. Validity and reliability of Allen and Meyer’s (1990) measure of employee commitment in the context of academic staff in universities in Uganda. J Sociol Educ Afr. 2016;14(1):1–9.

17. Fraenkel J, Wallen N, Hyun H. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education.

18. Saleh AM, Darawad MW, Al-Hussami M. Organizational commitment and work satisfaction among Jordanian nurses: a comparative study. Life Sci J. 2014;11(2):31–36.

19. Arbabisarjou A, Hamed S, Sadegh DM, Hassan R. Organizational commitment in nurses. Int J Adv Biotechnol Res. 2016;7(5):1841–1846.

20. Eleswed M, Mohammed F. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: a correlational study in Bahrain. Int J Bus Humanit Technol. 2013;3(5):44–53.

21. Singh A, Gupta B. Job involvement, organizational commitment, professional commitment, and team commitment. Benchmarking. 2015;22(6):1192–1211. doi:10.1108/BIJ-01-2014-0007

22. Alsayed S, West S. Exploring acute care workplace experiences of Saudi female nurses: creating career identity. Saudi Crit Care J. 2019;3:75–84. doi:10.4103/sccj.sccj_11_19

23. Aboshaiqah A. Strategies to address the nursing shortage in Saudi Arabia. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63(3):499–506. doi:10.1111/inr.12271

24. Nagar K. Organizational commitment and job satisfaction among teachers during times of burnout. Vikalpa. 2012;37(2):43–60. doi:10.1177/0256090920120205

25. Satoh M, Watanabe I, Asakura K. Factors related to affective occupational commitment among Japanese nurses. Open J Nurs. 2017b;7(03):449–462. doi:10.4236/ojn.2017.73035

26. Ariyani I, Haerani S, Maupa H, Taba MI. The influence of organizational culture, work motivation and working climate on the performance of nurses through job satisfaction, organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior in the private hospitals in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sci Res J. 2016;IV(VII, July 2016 Edition):15–29.

27. Elewa AH, Abed F. Nursing profession as perceived by staff nurses and its relation to their career commitment at different hospitals. Int J Nurs Didactics. 2017;7(01):13–22.

28. Naghneh MHK, Tafreshi MZ, Naderi M, Shakeri N, Bolourchifard F, Goyaghaj NS. The relationship between organizational commitment and nursing care behavior. Electron Physician. 2017;9(7):4835–4840. doi:10.19082/4835

29. Timalsina R, Sarala KC, Rai N, Chhantyal A. Predictors of organizational commitment among university nursing faculty of Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. BMC Nurs. 2018;17:30. doi:10.1186/s12912-018-0298-7

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.