Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 11

Are energy drinks unique mixers in terms of their effects on alcohol consumption and negative alcohol-related consequences?

Authors Johnson SJ, Alford C, Stewart K, Verster JC

Received 7 June 2017

Accepted for publication 8 August 2017

Published 5 January 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 15—23

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S143476

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Sean J Johnson,1 Chris Alford,1 Karina Stewart,2 Joris C Verster3–5

1Department of Health and Social Sciences, Psychological Sciences Research Group, University of the West of England, 2Department of Applied Sciences, Biomedical and Analytical Sciences, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK; 3Division of Pharmacology, Utrecht University, Utrecht 4Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands; 5Center for Human Psychopharmacology, Swinburne University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Introduction: Previous research has suggested that consuming alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AMED) increases overall alcohol consumption. However, there is limited research examining whether energy drinks are unique in their effects when mixed with alcohol, when compared with alcohol mixed with other caffeinated mixers (AOCM). Therefore, the aim of this survey was to investigate alcohol consumption on AMED occasions, to that on other occasions when the same individuals consumed AOCM or alcohol only (AO).

Methods: A UK-wide online student survey collected data on the frequency of alcohol consumption and quantity consumed, as well as the number of negative alcohol-related consequences reported on AO, AMED and AOCM occasions (N=250).

Results: Within-subjects analysis revealed that there were no significant differences in the number of alcoholic drinks consumed on a standard and a heavy drinking session between AMED and AOCM drinking occasions. However, the number of standard mixers typically consumed was significantly lower on AMED occasions compared with AOCM occasions. In addition, when consuming AMED, students reported significantly fewer days consuming 5 or more alcohol drinks, fewer days mixing drinks, and fewer days being drunk, compared with when consuming AOCM. There were no significant differences in the number of reported negative alcohol-related consequences on AMED occasions to AOCM occasions. Of importance, alcohol consumption and negative alcohol-related consequences were significantly less on both AMED and AOCM occasions compared with AO occasions.

Conclusion: The findings that heavy alcohol consumption occurs significantly less often on AMED occasions compared with AOCM occasions is in opposition to some earlier claims implying that greatest alcohol consumption occurs with AMED. The overall greatest alcohol consumption and associated negative consequences were clearly associated with AO occasions. Negative consequences for AMED and AOCM drinking occasions were similar, suggesting that energy drink was comparable with AOCM in this regard.

Keywords: alcohol, energy drinks, caffeine, alcohol consumption, consequences

Introduction

Despite a recent report that alcohol consumption is declining among young adults in the UK,1 it remains a significant issue among UK university students. For example, university students have been reported to drink more than their non-university peers and the general population,2,3 with 65% of female and 76% of male UK students reporting at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the previous 2 weeks.4 This is further highlighted by 41% of UK students reporting drinking alcohol with the deliberate intention of getting drunk at least once a week.5

In the short-term, this excessive alcohol consumption leads to a decrease in academic performance6 and an increased susceptibility to alcohol-related harms such as anti-social behavior,7 driving while intoxicated8 and engaging in unsafe sexual practices.9 It may also lead to acute intoxication and alcohol poisoning, resulting in hospital admission.10 Long-term consequences include health-related problems and an increased risk of dependency later in life.11 Hence, this excessive alcohol consumption practice not only has an impact on the student concerned, but also has wide-ranging social, health and economic implications and thus presents a serious public health problem.

Given the extent of this problem, in recent years, much research has concentrated on trying to understand the factors that may be driving this excessive consumption. One factor that has been linked to problematic student alcohol consumption is the rise in popularity of alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AMED) among this age group.

A substantial body of survey research has consistently found that those who mix alcohol with energy drinks consume significantly more alcohol more often and in higher quantities and experience more negative alcohol-related consequences12–16 than those who consume alcohol alone.

Early explanations for these observed differences focused on the idea that the stimulant effects of caffeine counteract the sedative effects of alcohol, leaving consumers feeling subjectively less intoxicated and therefore more likely to consume further quantities of alcohol and engage in riskier behaviors.17 However, evidence that AMED consumption reduces perception of intoxication is lacking, with a recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluding that “consuming alcohol with caffeinated beverages does not impair judgement of subjective intoxication”.18

More recently, some researchers19 have questioned the exclusive focus on energy drinks as a unique mixer when combined with alcohol, given that the purported active ingredient, caffeine, is also contained in many other beverages (e.g. cola) that are more frequently mixed with alcohol. Indeed, using a nighttime field study Rossheim and Thombs20 found that only 6% reported consuming AMED compared with 24% who consumed cola-caffeinated mixed drinks. Therefore, if caffeine is proven to be the driving force behind increased alcohol consumption and risk-taking behavior, then it would be important to inform both students and the wider public about the potential dangers of combining all sources of caffeine with alcohol. However, the current research evidence to support such recommendations is limited and the research that is available contains methodological flaws impacting cause-and-effect conclusions.

To date, only a few studies have differentiated between energy drinks and alcohol mixed with other caffeinated mixers (AOCM) when examining their effects on alcohol consumption. Thombs et al19 found that among bar patrons breath alcohol concentration in cola-caffeinated alcoholic beverage consumers was significantly higher than that in alcohol-only (AO) consumers. However, there were no significant differences in intoxication level between the cola-caffeinated alcoholic beverage group and AMED group. Similarly, Cobb et al21 found that although alcohol-caffeine consumption was associated with heavier drinking characteristics compared with AO consumption, there were few differences in overall drinking behavior between AMED consumers and alcohol mixed with caffeinated soda consumers. Kponee et al22 found that those who consumed caffeinated beverages with alcohol were more likely to drink larger amounts of alcohol more often than those who did not consume caffeinated beverages with alcohol. However, those who mixed alcohol with energy drinks (non-traditional caffeinated beverages) reported a higher frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed compared with those who mixed alcohol with traditional caffeinated drinks (e.g. soda). In contrast, although Penning et al23 found that those who mixed alcohol with cola or alcohol with energy drinks consumed more alcohol than those who consumed alcohol alone, mixing alcohol with cola was associated with greater alcohol consumption than AMED.

In analyzing this data, a recent systematic review McKetin et al concluded that “Comparatively little research has examined the effect of other caffeinated beverages, although existing research suggests that these may also be associated with elevated levels of drinking”.24 Although this between-group comparison research suggests that those who mix alcohol with caffeinated beverages in any form (energy drinks, cola etc.) consume more alcohol than those who consume alcohol only, this does not imply that mixing alcohol with caffeinated beverages causes increased alcohol consumption. While the observed differences in alcohol may be related to the co-consumption of caffeinated mixers, they could equally be argued to be related to the many phenotypical differences that may exist between the different groups. Indeed, it has been shown that AMED consumers are more often younger,25,26 and male,13,25–27 and are more likely to use illicit drugs,28,29 smoke28 and engage in high risk-taking behavior12,13,28–30 compared with AO consumers. In order to determine whether energy drinks play a role in affecting overall alcohol consumption, some researchers28,30,31 have utilized a within-subjects design. This approach compares alcohol consumption on AMED occasions with other occasions on which the same individual consumes AO, therefore controlling for the many between-group differences, such as increased alcohol intake or personality. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of both approaches32 found that although between-subjects comparisons suggest that AMED consumers drink more alcohol than AO consumers, within-subjects comparisons demonstrate that mixing alcohol with energy drinks has no significant impact on overall alcohol consumption.

Given the paucity and methodological limitations of previous research, it is clear that in order to determine whether energy drinks present a unique risk in increasing alcohol consumption and its associated negative consequences, further research utilizing a within-subjects design is required. Furthermore, given the worrying levels of excessive alcohol consumption among UK students and the popularity of alcohol and energy drink consumption among this population, the aim of this secondary analysis was to examine alcohol consumption and its associated negative consequences on AMED occasions, with other occasions on which the same student consumed AOCM, or AO.

Methods

Sample

All student unions (N=139) at universities throughout the UK were contacted and asked if they would be willing to advertise the student survey via their social media platforms (Facebook and Twitter). A third responded and agreed to assist, which involved distributing a short summary of the survey content and a web link. Participating student unions were asked to post the link to the survey on 3 occasions across the 5-week data collection period: on the opening day, half way through the data collection period and 1 week prior to the survey closing.

The web link contained a detailed information sheet that explained the purpose and content of the survey and that participation was anonymous and voluntary. Informed consent was obtained by participants clicking on an “I agree to participate” button that took them to the first survey question. In order to reduce the likelihood of non-response bias, upon completion of the study, those that wished to continue with the survey were entered into a monetary prize draw (1 × £500, 10 × £50). Prior to the study commencing, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of the West of England’s ethics committee.

A total of 2371 participants opened the link to the survey. Participants were excluded if they did not provide informed consent (7); did not meet the age criterion of 18–30 years (78); were non-students (192); did not answer the questions that were necessary to classify them as part of one of the drinking groups (211) or stated they did not answer all of the items truthfully (10). After cleaning the data, 1873 participants remained for analysis. For this paper, data were used for those that reported consuming both AMED, AOCM and AO on different drinking occasions (n=250).

Survey outline

The survey methodology has been described extensively elsewhere.33–35 In brief, the first part of the survey asked participants to provide demographic information as well as details relating to medication, smoking and drug use.

To assess alcohol consumption, items from the Quick Drinking Screen that measures the frequency and quantity of consumption across varying time scales (one occasion, past month, past year) were adapted to analyze 3 possible drinking occasions: consumption of alcohol alone (not mixed with energy drinks or other soft drinks); consumption of AMED; and consumption of alcohol mixed with other non-alcoholic beverages (e.g. cola, tonic). Mixing was defined as consuming the mixer within a time period of 2 hours before to 2 hours after alcohol consumption, allowing for the consumption of alcohol and mixer within the same drink and the consumption of a mixer between alcoholic drinks. Alcohol consumption was defined using standardized UK alcohol units (1 standard unit = 10 mL of pure alcohol)36 and 1 energy drink was standardized to 250 mL. When reporting mixing alcohol with other non-alcoholic beverages, participants had the option to choose the 1 mixer they usually preferred, then answer the consumption questions with reference to their chosen preferred mixer. The mixer was defined using pictures of commonly consumed non-alcoholic beverages of a similar volume. For the analysis in this paper, these mixers were further differentiated into caffeinated and non-caffeinated, based on their reported caffeine content.

In order to investigate negative alcohol-related consequences, the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ) was completed.37 In addition to the standard BYAACQ, following previous research,30,35 2 further items were included to determine whether participants were injured or got into a fight after alcohol consumption. Participants indicated whether the 24 standard items, and 2 additional items, were applicable to them in the past year for the particular drinking occasion in question (AO, AMED, AOCM). A higher score in the range of 0–24 indicated engagement with more negative alcohol-related consequences.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Data were collected online via SurveyMonkey® (Palo Alto, CA, USA), cleaned in Microsoft Excel and analyzed using the IBM statistics for windows version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The mean, SD and frequency distribution were computed for demographics, alcohol consumption and BYAACQ scores for occasions on which participants consumed AO, AMED and AOCM. In order to determine whether there were any differences in alcohol consumption between AO, AMED, AOCM drinking occasions, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Huynh–Feldt correction was conducted. For the BYAACQ data, a Cochran’s Q test was performed on single items and a repeated-measures ANOVA with a Huynh–Feldt correction on the total scores.

Results

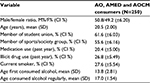

Of the 1873 participants who were identified as alcohol consumers, 13.3% (N=250) reported consuming alcohol alone, AMED and AOCM on different drinking occasions. On AOCM occasions, the majority of participants reported consuming alcohol mixed with cola (64.8%), with the remaining participants reporting mixing alcohol with diet cola (35.2%). As can be seen in Table 1. the proportion of males (50.8%) and females (49.2%) reporting all 3 of these consumption practices were similar, with a mean age of 20.5 years. Sixty-one point six percent identified as members of the student union and 55.6% as members of sports or society groups. Past year medication and illicit drug use was reported as 20.4% and 26.8%, respectively. The mean age at which participants first consumed alcohol was 13.8 years, and the mean age at which they began consuming alcohol regularly was 17.0 years.

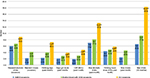

To investigate the impact of caffeine consumption on the frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed, within-subjects comparisons were performed comparing occasions on which participants consumed AO, with other occasions on which they consumed AMED and AOCM. A repeated-measures ANOVA with a Huynh–Feldt correction showed that there was a significant main effect of consumption occasion (AO, AMED and AOCM) on the frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed, across all consumption questions. Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction revealed a consistent pattern of significant differences (Figure 1), with participants consuming significantly less alcohol on AMED and AOCM occasions compared with AO occasions. For example, compared with AO occasions, when consuming AMED and AOCM, participants consumed significantly fewer alcoholic drinks during an average drinking session, reported significantly fewer drinking days and days drunk in the past month as well as significantly fewer occasions consuming more than 4 (female)/5 (male) alcoholic drinks. They also reported a lower total for the maximum number of alcoholic drinks consumed on a single occasion in the previous month, and the duration of alcohol consumption on this occasion was also significantly shorter when consuming AMED and AOCM than when consuming AO. Furthermore, when consuming AMED and AOCM, they consumed fewer alcoholic drinks on a single occasion in the previous year than when consuming AO. Finally, when consuming AMED and AOCM, participants consumed fewer alcoholic drinks on a single occasion in the previous year than when consuming AO.

Although there were no statistically significant differences in the number of alcohol drinks consumed on an average drinking session during AMED and AOCM occasions; on AMED occasions, participants reported significantly fewer drinking days and days drunk in the past month and significantly fewer occasions consuming more than 4 (female)/5 (male) alcoholic drinks compared with AOCM occasions. In addition, while there were no significant differences in the maximum number of alcoholic drinks consumed on a single occasion in the previous month, the number of hours spent consuming alcohol on this occasion was significantly shorter on AMED occasions compared with AOCM occasions. Furthermore, when consuming AMED, they consumed fewer alcoholic drinks on a single occasion in the previous year than when consuming AOCM. Finally, the number of mixers consumed with alcohol on a usual drinking occasion and the greatest number of mixers consumed with alcohol in the past month were significantly lower on AMED occasions compared with AOCM occasions.

Of the 250 participants that reported the frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed on AO, AMED and AOCM occasions, 232 reported associated alcohol-related consequences (Table 2). A Cochran’s Q test determined that there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of participants reporting each of the negative alcohol-related consequences across AO, AMED and AOCM occasions. The only negative alcohol-related consequence that did not reach significance was “I have felt badly about myself because of my drinking”.

Post hoc analysis using Bonferroni correction revealed that across the majority of statements when consuming AMED or AOCM, negative alcohol-related consequences were experienced significantly less frequently than when consuming AO. The only statements that were not significantly different following post hoc analysis were “I have driven a car when I knew I had too much to drink to drive safely”, “I have felt like I needed a drink after I’d gotten up” and “I have got into a fight after drinking”.

For the majority of statements, there were no significant differences in the proportion of participants reporting negative alcohol-related consequences on AMED occasions compared with AOCM occasions. The exceptions to this were “I have often ended up drinking on nights when I had planned not to drink”, which was reported more on AOCM occasions and “when drinking, I have done impulsive things I regretted later”, which was reported more on AMED occasions.

The total BYAACQ score was significantly lower on AMED and AOCM occasions compared with AO occasions. However, there was no significant difference in the total BYAACQ score on AMED occasions compared with AOCM occasions.

Discussion

The results of this survey demonstrate that AMED is consumed significantly less often and at lower levels of intoxication compared with consuming AOCM. In addition, it was found that when mixing alcohol with caffeinated mixers in any form (energy drinks or AOCM, such as cola), the frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed and engagement in negative alcohol-related consequences were significantly less than when consuming alcohol alone.

These findings have several important implications. First, they contrast with previous between-subjects research, which has inappropriately reached casual conclusions on the relationship between mixing caffeinated beverages with alcohol and increased alcohol consumption. By comparing drinking occasions on which different caffeinated mixers or AO were consumed by the same individuals, the present study controlled for the many phenotypical differences that have been shown to exist between those who mix different caffeinated mixers with alcohol and those who do not, including higher levels of sensation-seeking and risk-taking behaviors.16,28,29,38–40 Therefore, any differences in alcohol consumption or negative alcohol-related consequences can be assumed to be caused by the co-consumption of alcohol with the particular caffeinated mixer. By utilizing this more appropriate within-subjects design, the current findings suggest that there is no causal relationship between consuming caffeinated beverages and increased alcohol consumption, but that the previous between-subject findings of increased alcohol consumption among caffeinated-alcohol consumers may indicate a predisposition to risky behavior that precedes and results in the engagement with caffeinated mixer use.41,42

However, what is not clear from this survey and some other within-subject studies28,30 is why there is decreased alcohol consumption on caffeinated mixer occasions (AMED and AOCM) compared with AO occasions. Future research could usefully examine the biological, social, personal and economic reasons that may underlie this pattern of drinking behavior. Some suggested explanations include animal studies that have indicated the possible role of energy drink ingredients, such as taurine, in reducing subsequent alcohol consumption.43 More recently, a meta-analysis44 has found that sugars, including low energy sweeteners found in energy drinks, have a suppressive effect on appetite. A simpler explanation for reduced alcohol consumption on caffeinated mixer occasions may be that because the volume of the mixer would be additional to the volume of the alcoholic drink, the increased total liquid intake due to mixing may result in the drinker feeling replete, and therefore, not wanting to drink additional liquids in the form of alcohol. Furthermore, the increased volume of mixer and alcohol may slow the pace of consumption versus alcohol alone, therefore, slowing intoxication. For example, it takes longer to drink a rum (25 mL) and coke (250 mL) than a shot of rum (25 mL) alone. In fact, consuming non-alcoholic beverages in between alcoholic beverages is one of the protective behavioral strategies recommended by the National Health Service Change 4 Life programme.45 Promotion of such guidance among UK students may help in reducing the worrying levels of alcohol consumption and related consequences. Indeed, regardless of the consumption occasion, the majority of students consumed alcohol above the levels generally accepted as safe in the UK.

Second, the finding that AMED is consumed significantly less often and at lower levels of intoxication compared with consuming AOCM indicates that the current public health concern regarding energy drinks being a unique mixer is unwarranted. This is particularly the case given that the purported active ingredient in increasing alcohol consumption, caffeine, is consumed at similar levels across consumption occasions and that more traditional mixers (such as cola) are consumed more often with alcohol than energy drinks are. For example, in the present study, students reported more days drinking and more days drunk on AOCM occasions than on AMED occasions. Despite the call for educational programs, interventions and regulatory change to address the suggested problems associated with caffeinated-alcohol consumption,39,42 particularly AMED, as indicated by other researchers,32 this focus may be downplaying the wider concern of excessive alcohol consumption per se. It is clear that additional research utilizing more appropriate research designs, such as ecological momentary assessment,46 is required before such substantive claims can be made.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our research that need to be acknowledged. First, this survey relied on the retrospective recall of alcohol consumption during past drinking occasions of varying timeframes (30 days, 12 months), in which high levels of alcohol were reportedly consumed. Although, by using a within-subjects design, there is no reason to assume any recall bias between the different drinking occasions. In addition, the recall examined global associations between the drinking occasion (AMED, AOCM or AO), alcohol consumption and associated negative consequences without linking behaviors to specific events. Therefore, this survey was unable to capture the many event-level factors that may mediate the relationship between these variables. Furthermore, the consumption of just 1 mixed beverage resulted in the drinker being classed as part of this drinking group, regardless of the many other drinks that may have been consumed within the same occasion. In addition, it was not possible to differentiate between different beverage types within each category, for example, Red Bull versus Monster. To overcome these limitations, methodological advances are required, including real-time collection of alcohol consumption and its related consequences.

An additional limitation is that convenience sampling was used via social media. Therefore, it was not possible to determine the response rate and marginalized sections of the student population may not have taken part. However, the demographic of the current sample did broadly reflect that of the general student population in the UK.47 Finally, given the unique drinking patterns of students evidenced,2,3 it is not possible to generalize these results beyond this population. Additional research among different sub-populations may yield contrasting findings. It is also of importance to replicate these findings in the UK, and in other countries.

Conclusion

Alcohol is consumed significantly less often on AMED occasions compared with AOCM occasions. The increased alcohol consumption on AO occasions compared with AMED and AOCM occasions confirms that mixing alcohol with caffeinated beverages does not increase total alcohol consumption. Our data suggest that future research should focus on excessive alcohol consumption per se.

Acknowledgments

This survey was financially supported by Red Bull GmbH as part of a PhD studentship. Red Bull GmbH had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

These findings were presented at the 39th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, June 25–29, New Orleans, LA, USA.

The authors are grateful to the UK university student unions who advertised the survey and the students who took the time to participate.

Author contributions

SJJ led the study presented in this paper; collected, analyzed, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. CA, JCV and KS participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped to draft and review the manuscript. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

SJJ has been involved in sponsored research for Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Merck, Gilead, Novartis, Roche and Red Bull GmbH. CA has undertaken sponsored research, or provided consultancy, for a number of companies and organizations, including Airbus Group Innovations, Astra, British Aerospace/BaeSystems, Civil Aviation Authority, Duphar, FarmItalia Carlo Erba, Ford Motor Company, ICI, Innovate UK, Janssen, LERS Synthélabo, Lilly, Lorex/Searle, Ministry of Defense, Quest International, Red Bull GmbH, Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Sanofi Aventis. JCV has received grants/research support from The Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment, Janssen Research and Development, Nutricia, Takeda, Red Bull, and has acted as a consultant for Canadian Beverage Association, Centraal Bureau Drogisterijbedrijven, Coleman Frost, Danone, Deenox, Eisai, Janssen, Jazz, Purdue, Red Bull, Sanofi-Aventis, Sen-Jam Pharmaceutical, Sepracor, Takeda, Transcept, Trimbos Institute, and Vital Beverages. KS reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Orchard C. Adult drinking habits in Great Britain; 2013. 2015. | ||

Balodis IM, Potenza MN, Olmstead MC. Binge drinking in undergraduates: relationships with sex, drinking behaviors, impulsivity, and the perceived effects of alcohol. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20(5–6):518–526. | ||

Gill JS. Reported levels of alcohol consumption and binge drinking within the UK undergraduate student population over the last 25 years. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(2):109–120. | ||

El Ansari W, Sebena R, Stock C. Socio-demographic correlates of six indicators of alcohol consumption: survey findings of students across seven universities in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Arch Public Health. 2013;71(1):29. | ||

National Union of Students. Students and Alcohol 2016 Research into students relationship with alcohol; 2016. | ||

Howland J, Rohsenow DJ, Littlefield CA, et al. The effects of binge drinking on college students’ next-day academic test-taking performance and mood state. Addiction. 2010;105(4):655–665. | ||

Richardson A, Budd T. Young adults, alcohol, crime and disorder. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2003;13(1):5–16. | ||

Hingson RW, Heeren T, Zakocs RC, Kopstein A, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among US college students ages 18–24. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(2):136–144. | ||

Standerwick K, Davies C, Tucker L, Sheron N. Binge drinking, sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infection in the UK. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(12):810–813. | ||

National Health Service. Alcohol Poisoning. 2016; Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/alcohol-poisoning/Pages/introduction.aspx. Accessed March 31, 2017. | ||

Jennison KM. The short-term effects and unintended long-term consequences of binge drinking in college: a 10-year follow-up study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(3):659–684. | ||

Brache K, Stockwell T. Drinking patterns and risk behaviors associated with combined alcohol and energy drink consumption in college drinkers. Addict Behav. 2011;36(12):1133–1140. | ||

Eckschmidt F, De Andrade AG, Dos Santos B, De Oliveira LG. The effects of alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AmED) on traffic behaviors among Brazilian college students: a national survey. Traffic Inj Prev. 2013;14(7):671–679. | ||

Flotta D, Micò R, Nobile CG, Pileggi C, Bianco A, Pavia M. Consumption of energy drinks, alcohol, and alcohol-mixed energy drinks among Italian adolescents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(6):1654–1661. | ||

O’Brien MC, McCoy TP, Egan KL, Goldin S, Rhodes SD, Wolfson M. Caffeinated alcohol, sensation seeking, and injury risk. J Caffeine Res. 2013;3(2):59–66. | ||

Berger L, Fendrich M, Fuhrmann D. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: Are there associated negative consequences beyond hazardous drinking in college students? Addict Behav. 2013;38(9):2428–2432. | ||

Marczinski CA. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: consumption patterns and motivations for use in US college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(8):3232–3245. | ||

Benson S, Verster JC, Alford C, Scholey A. Effects of mixing alcohol with caffeinated beverages on subjective intoxication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;47:16–21. | ||

Thombs D, Rossheim M, Barnett TE, Weiler RM, Moorhouse MD, Coleman BN. Is there a misplaced focus on AmED? Associations between caffeine mixers and bar patron intoxication. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116(1–3):31–36. | ||

Rossheim ME, Thombs DL. Artificial sweeteners, caffeine, and alcohol intoxication in bar patrons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(10):1891–1896. | ||

Cobb CO, Nasim A, Jentink K, Blank MD. The role of caffeine in the alcohol consumption behaviors of college students. Subst Abus. 2015;36(1):90–98. | ||

Kponee KZ, Siegel M, Jernigan DH. The use of caffeinated alcoholic beverages among underage drinkers: results of a national survey. Addict Behav. 2014;39(1):253–258. | ||

Penning R, de Haan L, Verster JC. Caffeinated drinks, alcohol consumption and hangover severity. Open Neuropsychopharmacol J. 2011;4:36–39. | ||

McKetin R, Coen A, Kaye S. A comprehensive review of the effects of mixing caffeinated energy drinks with alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;151:15–30. | ||

Berger LK, Fendrich M, Chen H, Arria AM, Cisler RA. Sociodemographic correlates of energy drink consumption with and without alcohol: results of a community survey. Addict Behav. 2011;36(5):516–519. | ||

Wells BE, Kelly BC, Pawson M, LeClair A, Parsons JT, Golub SA. Correlates of concurrent energy drink and alcohol use among socially active adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39(1):8–15. | ||

Cheng WJ, Cheng Y, Huang MC, Chen CJ. Alcohol dependence, consumption of alcoholic energy drinks and associated work characteristics in the Taiwan working population. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47(4):372–379. | ||

Haan L, Haan H, Palen J, Olivier B, Verster JC. Effects of consuming alcohol mixed with energy drinks versus consuming alcohol only on overall alcohol consumption and negative alcohol-related consequences. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:953–960. | ||

Snipes DJ, Benotsch EG. High-risk cocktails and high-risk sex: examining the relation between alcohol mixed with energy drink consumption, sexual behavior, and drug use in college students. Addict Behav. 2013;38(1):1418–1423. | ||

Woolsey C, Waigandt A, Beck NC. Athletes and energy drinks: reported risk-taking and consequences from the combined use of alcohol and energy drinks. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2010;22(1):65–71. | ||

Verster JC, Benjaminsen J, van Lanen J, van Stavel N, Olivier B. Effects of mixing alcohol with energy drink on objective and subjective intoxication: results from a Dutch on-premise study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232(5):835–842. | ||

Verster JC, Benson S, Johnson SJ, Scholey A, Alford C. Mixing alcohol with energy drink (AMED) and total alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2016;31(1):2–10. | ||

Johnson SJ, Alford C, Stewart K, Verster JC. A UK student survey investigating the effects of consuming alcohol mixed with energy drinks on overall alcohol consumption and alcohol-related negative consequences. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:496–501. | ||

Johnson SJ, Alford C, Verster JC, Stewart K. Motives for mixing alcohol with energy drinks and other non-alcoholic beverages and its effects on overall alcohol consumption among UK students. Appetite. 2016;96:588–597. | ||

de Haan L, de Haan H, Olivier B, Verster JC. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: methodology and design of the Utrecht Student Survey. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:889–898. | ||

National Health Service. Alcohol Units; 2015. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/alcohol/Pages/alcohol-units.aspx. Accessed April 2017. | ||

Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: the brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(7):1180–1189. | ||

Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Kasperski SJ, et al. Increased alcohol consumption, nonmedical prescription drug use, and illicit drug use are associated with energy drink consumption among college students. J Addict Med. 2010;4(2):74–80. | ||

Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Kasperski SJ, Vincent KB, Griffiths RR, O’Grady KE. Energy drink consumption and increased risk for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(2):365–375. | ||

Miller KE. Energy drinks, race, and problem behaviors among college students. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(5):490–497. | ||

Howland J, Rohsenow DJ, Arnedt JT, et al. The acute effects of caffeinated versus non-caffeinated alcoholic beverage on driving performance and attention/reaction time. Addiction. 2011;106(2):335–341. | ||

Howland J, Rohsenow DJ. Risks of energy drinks mixed with alcohol. JAMA. 2013;309(3):245–246. | ||

Olive MF. Interactions between taurine and ethanol in the central nervous system. Amino Acids. 2002;23(4):345–357. | ||

Rogers PJ, Hogenkamp PS, de Graaf C, et al. Does low-energy sweetener consumption affect energy intake and body weight? A systematic review, including meta-analyzes, of the evidence from human and animal studies. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40(3):381–394. | ||

National Health Service. Change 4 Life: Easy drink swaps; 2017. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Change4Life/Pages/alcohol-drink-swaps.aspx. Accessed April, 07, 2017. | ||

Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol Assess. 2009;21(4):486–497. | ||

Universities UK. Patterns and Trends in UK Higher Education; 2013. Available from: http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/highereducation/Documents/2013/PatternsAndTrendsinUKHigherEducation2013.pdf. Accessed April 07, 2017. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.