Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 7

An unusual case of malignancy-related hypercalcemia

Received 10 July 2013

Accepted for publication 10 September 2013

Published 6 December 2013 Volume 2014:7 Pages 21—27

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S51302

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 6

Mary-Anne Doyle, Janine C Malcolm

Division of Endocrinology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Objective: To report the case of a 28-year-old woman who presented with hypercalcemia (total calcium =4.11 mmol/L), elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) 24.6 pmol/L, normal parathyroid hormone-related peptide 7.8 pg/mL, and a 63 mm × 57 mm, poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (small-cell type) pancreatic mass with liver metastases.

Investigations and treatment: Hypercalcemia was acutely managed with intravenous fluids, pamidronate and calcitonin. Investigations for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and parathyroid adenoma were initiated. The identified neuroendocrine tumor was treated with cisplatinum/etoposide chemotherapy.

Results: The pancreatic mass (56 mm × 49 mm) and metastases decreased in size with chemotherapy and calcium levels normalized. Eight months later, calcium increased to 3.23 mmol/L, PTH increased to 48.2 pmol/L, and the pancreatic mass increased in size to 67 mm × 58 mm. The patient was given a trial of cinacalcet but was unable to tolerate it. Chemotherapy was restarted and resulted in a decrease in the pancreatic mass (49 mm × 42 mm), a reduction in PTH levels (16.6 pmol/L), and calcium levels (2.34 mmol/L).

Conclusion: Ectopic PTH secreting tumors should be considered when there is no parathyroid related cause for an elevated PTH. Recognizing the association between PTH and hypercalcemia of malignancy may lead to an earlier detection of an undiagnosed malignancy.

Keywords: hypercalcemia of malignancy, parathyroid hormone, parathyroid hormone related-peptide, neuroendocrine tumor

Introduction

Hypercalcemia is a common metabolic disorder with multiple etiologies, of which primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause.1 Hypercalcemia can occur at any age but occurs most often in patients over the age of 50.2 It is most commonly due to either a single adenoma or hyperplasia of the parathyroid gland. Hypercalcemia may also be part of a hereditary syndrome (multiple endocrine neoplasia [MEN1] or multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A [MEN2A]) particularly when identified in children or young adults.2,3 Parathyroid lesions are routinely identified with 99 mTc-Sestamibi scintigraphy scans and often successfully treated with surgical resection.

Hypercalcemia is also a well-established paraneoplastic condition that is associated with many malignancies and may occur through a number of different mechanisms (Table 1). In 1941, Albright4 was first to suggest that humoral factors secreted by cancer cells caused bone resorption and impaired renal calcium excretion.4 Parathyroid hormone (PTH) was originally thought to be the humoral factor that caused hypercalcemia of malignancy, however, in 1987 PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) was found to be the primary mediator associated with malignancy-induced hypercalcemia.5–8 In such cases, patients often have suppressed PTH levels, metabolic alkalosis and low 1, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D levels.9

Since the discovery of PTHrP, there have been only rare cases of ectopic production of PTH by neuroendocrine tumors reported in the literature.10–26 In contrast to PTHrP-secreting tumors, patients with elevated PTH levels are often found to have normal PTHrP levels, hyperchloremic acidosis and elevated 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D levels.9

We present a rare case of malignancy associated hypercalcemia secondary to ectopic PTH. We will review previously reported cases of PTH-secreting tumors, discuss the differences in biochemical findings between humoral causes of hypercalcemia,27–31 and possible treatment options for management of hypercalcemia caused by PTH secreting tumors.

Case report

Background

A previously healthy 28-year-old presented to hospital with a 2-week history of nausea, fatigue, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Initial laboratory investigations showed severe hypercalcemia (Ca =4.11 mmol/L, N=2.20–2.52 mmol/L) and acute renal failure (creatinine =215 μmol/L, N=35–88 μmol/L). Other laboratory investigations are summarized in Table 2. An electrocardiography (ECG) showed a normal sinus rhythm of 74 beats per minute and a corrected QT interval of 395.

Treatment and investigations

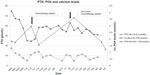

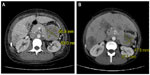

Following therapy with intravenous (IV) fluids, pamidronate disodium (60 mg IV), and calcitonin (200 units twice daily), her serum calcium improved to 2.82 mmol/L within 3 days. Further investigations revealed an elevated serum PTH level at 24.6 pmol/L (1.6–9.3 pmol/L, intact PTH immunometric assay) and a high circulating 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D level at 229 pmol/L (29–193 pmol/L) (Figure 1 and Table 2). This raised the possible diagnoses of primary hyperparathyroidism or MEN1. There was no family history of either of these disorders. Ongoing abdominal discomfort despite improvements in calcium levels resulted in a diagnostic abdominal ultrasonography being performed, which showed a 6.0 × 6.7 × 8.0 cm solid mass between the stomach and tail of the pancreas with multiple liver metastases. A computed tomography scan (CT-scan) showed a large 63 × 57 mm mass that was inseparable from the pancreas in the lesser sac infiltrating the splenic artery (Figure 2). An ultrasonography-guided core biopsy of the liver metastases revealed a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the small-cell type consistent with the pancreas as the primary site of malignancy. Investigations to identify the source of PTH secretion including a CT-scan of the neck and 99mTc-sestamibi scintigraphy scan failed to find evidence of a parathyroid adenoma. Further staging investigations, including pituitary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and genetic testing for MEN1, were negative. A skeletal survey did not show any bony abnormalities and bone mineralization was normal throughout. A bone scan did not show any evidence of metastatic disease. The patient did not suffer any pathologic fractures. A bone density scan was not performed.

Treatment course

After one round of chemotherapy treatment with cisplatinum (40 mg IV) and etoposide (160 mg IV), there was a decrease in the size of the pancreatic mass (56 mm × 49 mm) and liver metastases. With shrinkage of the tumor, calcium and PTH levels also decreased (Ca 2.02 mmol/L, PTH 21.2 pmol/L) (Figure 1). At the request of the patient, chemotherapy was stopped after six cycles.

Eight months later, she was readmitted with recurrent hypercalcemia (Ca 3.23 mmol/L). An abdominal CT-scan showed an increase in the size of the pancreatic mass (67 mm × 58 mm). Her serum PTH level was increased (48.2 pmol/L), whereas PTHrP levels were within normal limits (7.8 pg/mL, 1–15pg/mL) (Figure 1). The patient was treated with IV fluids and multiple doses of bisphosphonates (zoledronic acid 4 mg, pamidronate disodium 60 mg) and given a trial of cinacalcet hydrochloride 30 mg twice daily. The patient was not able tolerate the cinacalcet for more than 2 days before it was discontinued because of worsening nausea.

Chemotherapy was restarted with doxorubicin 74 mg IV, vincristine 1.8 mg IV, and cyclophosphamide 1480 mg IV. After the first cycle, her calcium levels normalized (2.34 mmol/L) and following the second cycle, her PTH level decreased to 16.6 pmol/L (Figure 1). A repeat CT scan of her abdomen also showed a reduction in the size of the pancreatic mass (49 mm × 42 mm) (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining of tissue from liver biopsy was done but failed to show evidence of PTH immunoreactivity within the tumor cells.

Despite chemotherapy, the patient died 15 months after diagnosis from recurrent hypercalcemia. An autopsy was declined by her family.

Discussion

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are uncommon, with an incidence of 1 per 100,000 patients per year.32 Clinical presentation and symptoms correlate with the functionality of the tumor and the type of hormones that are overexpressed. Among this type of malignancy, insulin-secreting pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are the most common, followed by gastrinomas, glucagonoma, vasoactive intestinal peptide secreting tumors (VIPomas), and somatostatinomas.33 PTH-secreting pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are rare, with the present case being only the third reported in the literature to date.

Hypercalcemia associated with a high PTH level commonly results from a primary parathyroid disorder. This was initially suspected in our patient. However, the clinical and biochemical findings in our case provide evidence to suggest that this pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor was secreting ectopic PTH. In our patient, serum calcium and PTH levels were found to be elevated, and PTHrP remained in the normal range. Despite a number of imaging modalities, there was no evidence of a parathyroid adenoma or hyperplasia to explain the high PTH levels. Chemotherapy treatment led to a reduction of the pancreatic tumor, normalization of calcium levels, and a reduction in PTH levels.

Although paraneoplastic secretion of PTH is not commonly known to cause hypercalcemia of malignancy it has been described in association with a number of different malignancies (Table 3). In the few cases reported to date, it appears to be more common in males (11 of 17 cases reported)10–12,16–18,22–26 and predominantly affects those over the age of 60 (14 of 17 cases).10–14,16,17,19,21–26 This is only the second case report of ectopic PTH production in a patient under the age of 30.18

As summarized in Table 3, a number of techniques have been reported in the literature as being used to confirm the diagnosis of hypercalcemia secondary to ectopic PTH production. Immunohistochemical staining for PTH in tissue samples from the liver metastases was attempted in our patient; however, these were negative. The negative results may have been due to the quality of biopsy, the immunohistochemical staining antibody that was used, differences between metastatic tissue and primary malignancy, ectopic hormone production being restricted to a subpopulation of tumor cells, or structural differences between the ectopic and the natural form of the hormone not detected with immunohistochemical staining. A biopsy of the primary pancreatic mass was not performed as the procedure was not in the best interest of the patient. The cancer diagnosis was obtained from the biopsy of the liver metastases and therefore tissue from the primary tumor was not available for PTH staining.

Although PTH mRNA was not available at our center, other authors have successfully demonstrated ectopic PTH production by comparing PTH mRNA sequencing from tumor extracts to PTH mRNA from parathyroid tissue using northern blot analysis.10,14,18,21 Despite the lack of immunohistochemical staining or PTH mRNA to confirm ectopic production of PTH, the reduction in tumor burden and improvements in calcium and PTH levels with chemotherapy provides good evidence of PTH secretion from this neuroendocrine tumor.

Outcomes with ectopic PTH secretion are variable, as described in Table 2. In almost half of the studies reported, patients succumbed to their disease shortly after diagnosis. Resistant hypercalcemia resulted in only transient improvements with standard therapy for hypercalcemia such as fluids and bisphosphonates reported in some cases of ectopic PTH secretion.10,20,21 Our patient had a similar course prior to the second course of chemotherapy, wherein the patient required weekly dosing of intravenous bisphosphonates and large amounts of IV fluids to maintain calcium levels at a reasonable albeit elevated level. A positive prognosis and long-term management of hypercalcemia in ectopic PTH secretion appears to be limited to resection of the malignancy or treatment with chemotherapy. There have been cases of hepatocellular carcinoma with a tumor producing intact PTH described where hypercalcemia was successfully controlled through transcatheter arterial embolization.16,17

Another option for management of severe or resistant hypercalcemia caused by hyperparathyroidism may be cinacalcet. Cinacalcet is a calcimimetic that increases the sensitivity of the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) and has been shown to reduce both calcium and PTH levels in other forms of hyperparathyroidism.34 Cinacalcet was tried in our patient, but unfortunately it was not tolerated because of inducing severe nausea and vomiting. We are not aware of any other case reports where this therapy has been used to treat ectopic PTH secretion.

The benefit of cinacalcet may extend beyond the calcium lowering effects. The CaSR is known to be expressed in a number of tissues not classically considered to play a role in calcium regulation.35 Recent studies have found that CaSR expression and activity in various tissues correlates with both malignancy proliferation and suppression. In breast and prostate cancer, increased expression and activity of CaSR may facilitate bone metastases.36,37 In contrast, parathyroid carcinomas have been associated with decreased or absent expression of the CaSR.38 Animal studies have demonstrated that cinacalcet leads to both activation and increased expression of the CaSR, suppression of parathyroid hyperplasia and reduced PTH secretion in rodents with secondary hyperparathyroidism.39 It is possible that the CaSR may also play a role in ectopic-PTH producing malignancies, and that cinacalcet may have the potential benefit of suppressing the proliferation of PTH-secreting tumor cells. Although further research is required, the potential role of the CaSR to influence tumor growth and suppression presents a novel and important target for investigation of new malignancy therapies.

Conclusion

Hypercalcemia of malignancy resulting from ectopic production of PTH, although not common, should be considered when PTH levels are significantly elevated and there is no evidence of a parathyroid-related cause. Recognizing the association between elevated PTH levels and hypercalcemia of malignancy may prevent unnecessary parathyroid or exploratory neck surgeries and also could possibly lead to the early detection of an undiagnosed malignancy. More research is needed to determine whether there is a role for calcimimetics in treating resistant hypercalcemia secondary to ectopic PTH production and on the potential for suppressing tumor growth in these circumstances.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Andrew Karaplis and Dr Dibyendu Panda (Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University) for their assistance with the immunohistochemistry staining.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

Al-Azem H, Khan A. Primary hyperparathyroidism. CMAJ. 2011;183(10):E685–E689. | |

Consensus Development Task Force on Diagnosis and Management of Asymptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism . Asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: standards and guidelines for diagnosis and management in Canada: Position paper. Endocr Pract. 2003;9(5):400–405. Available at http://www.stjoes.ca/pdfs/PHPT%20position2003.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2013. | |

Marcocci C, Cetani F. Clinical practice. Primary hyperparathyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(25):2389–2397. | |

Albright F. Case 27461. N Engl J Med. 1941;225(20):789–791. | |

Moseley JM, Kubota M, Diefenbach-Jagger H, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein purified from a human lung cancer cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(14):5048–5052. | |

Burtis W, Wu T, Bunch C, et al. Identification of a novel 17, 000-dalton parathyroid hormone-like adenylate cyclise-stimulating protein from a tumour associated with humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(15):7151–7156. | |

Strewler GJ, Stern PH, Jacobs Jw, et al. Parathyroid hormonelike protein from human renal carcinoma cells. Structural and functional homology with parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest. 1987;80(6):1803–1807. | |

Suva LJ, Winslow GA, Wettenhall RE, et al. A parathyroid hormone-related protein implicated in malignant hypercalcemia: cloning and expression. Science. 1987;237(4817):893–896. | |

Mundy GR, Edwards JR. PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) in hypercalcemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(4):672–675. | |

Yoshimoto K, Yamasaki R, Sakai H, et al. Ectopic production of parathyroid hormone by small cell lung cancer in a patient with hypercalcemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68(5):976–981. | |

Neilsen PK, Rasmussen AK, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Brandt M, Christensen L, Olgaard K. Ectopic production of intact parathyroid hormone by a squamous cell lung carcinoma in vivo and in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3793–3796. | |

Uchimura K, Mokuno T, Nagasaka A, et al. Lung cancer associated with hypercalcemia induced by concurrently elevated parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related protein levels. Metabolism. 2002;51(7):871–875. | |

Weiss ES, Doty J, Brock MV, Halvorson L, Yang SC. A case of ectopic parathyroid hormone production by a pulmonary neoplasm. J Thorac Cardiovascular Surg. 2006;131(4):923–924. | |

Nussbaum SR, Gaz RD, Arnold A. Hypercalcemia and ectopic secretion of parathyroid hormone by an ovarian carcinoma with rearrangement of the gene for parathyroid hormone. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(19):1324–1328. | |

Chen L, Dihn TA, Haque A. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary with hypercalcemia and ectopic parathyroid hormone production. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129(4):531–533. | |

Koyoma Y, Ishijima H, Ishibashi A, et al. Intact PTH-producing hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24(2):144–146. | |

Mahoney EJ, Monchik JM, Donatini G, De Lellis R. Life-threatening hypercalcemia from a hepatocellular carcinoma secreting intact parathyroid hormone: localization by sestamibi single-photon emission computed tomographic imaging. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(3):302–306. | |

Rizzoli R, Pache J-C, Diderjean L, Bürger A, Bonjour JP. A thymoma as a cause of true ectopic hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(3):912–915. | |

Iguchi H, Miyagi C, Tomita K, et al. Hypercalcemia caused by ectopic production of parathyroid hormone in a patient with papillary adenocarcinoma of the thyroid gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(8):2653–2657. | |

Vacher-Coponat H, Opris A, Denizot A, Dussol P, Berland Y. Hypercalcemia induced by excessive parathyroid hormone secretion in a patient with a neuroendocrine tumour. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(12):2832–2835. | |

VanHouten JN, Yu N, Rimm D, et al. Hypercalcemia of malignancy due to ectopic transactivation of the parathyroid hormone gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(2):580–583. | |

Eid W, Wheeler TM, Sharma MD. Current hypercalcemia due to ectopic production of parathyroid hormone-related protein and intact parathyroid hormone in a single patient with multiple malignancies. Endocr Pract. 2004;10(2):125–134. | |

Strewler GJ, Budayr AA, Clarck OH, Nissenson RA. Production of parathyroid hormone by a malignant nonparathyroid tumour in a hypercalcemic patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76(5):1373–1375. | |

Wong K, Tsuda S, Mukai R, Sumida K, Arakaki R. Parathyroid hormone expression in a patient with metastatic nasopharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma and hypercalcemia. Endocrine. 2005;25(1):83–86. | |

Kandil E, Noureldine S, Khalek M, Daroca P, Friedlander P. Ectopic secretion of parathyroid hormone in a neuroendocrine tumour: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2011;4(3):234–240. | |

Nakajima K, Tamai M, Okaniwa S, et al. Humoral hypercalcemia associated with gastric carcinoma secreting parathyroid hormone: a case report and review of the literature. Endocr J. 2013;60(5):557–562. | |

Stewart AF. Hypercalcemia associated with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(4):373–379. | |

Shu ST, Martin CK, Thudi NK, Dirksen WP, Rosol TJ. Osteolytic bone resorption in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(4):702–714. | |

Syed M, Horwitz M, Tedesco M, Garcia-Ocaña A, Wisniewski SR, Stewart AF. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (1–36) stimulates renal tubular calcium reabsorption in normal human volunteers: implications for the pathogenesis of humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1525–1531. | |

Schilling T, Pecherstorfer M, Blind E, Leidig G, Ziegler R, Raue F. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) does not regulate 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D serum levels in hypercalcemia of malignancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76(3):801–803. | |

Moe SM. Disorders involving calcium, phosphorus and magnesium. Primary Care. 2008;35(2):215–237. | |

Klimstra DS. Nonductal neoplasms of the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20 Suppl 1:S94–S112. | |

Muniraj T, Vignesh S, Shetty S, Thiruvengadam S, Aslanian JR. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Dis Mon. 2013;59(1):5–19. | |

Wüthrich R, Martin D, Bilezikian J. The role of calcimimetics in the treatment of hyperparathyroidism. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37(12):915–922. | |

Brennan SC, Thiem U, Roth S, et al. Calcium sensing receptor signalling in physiology and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(7):1732–1744. | |

Mihai R, Stevens J, McKinney C, Ibrahim NB. Expression of the calcium receptor in human breast cancer-a potential new marker predicting the risk of bone metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32(5):511–515. | |

Liao J, Schneider A, Datta NS, McCauley LK. Extracellular calcium as a candidate mediator of prostate cancer skeletal metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66(18):9065–9073. | |

Haven CJ, van Puijenbroek M, Karperien M, FLeuren GJ, Morreau H. Differential expression of the calcium receptor and combined loss of chromosome 1q and 11q in parathyroid carcinoma. J Pathol. 2004;202(1):86–94. | |

Miller G, Davis J, Shatzen E, Colloton M, Martin D, Henley CM. Cinacalcet HCL prevents development of parathyroid gland hyperplasia and reverses established parathyroid gland hyperplasia in a rodent model of CKD. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(6):2198–2205. |

© 2013 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2013 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.