Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 12

An online survey of Turkish psychiatrists’ attitudes about and experiences of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in clinical practice

Authors Altın M , Altın GE, Semerci B

Received 16 April 2016

Accepted for publication 30 June 2016

Published 4 October 2016 Volume 2016:12 Pages 2455—2461

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S110720

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Murat Altın,1 Gamze Ergil Altın,2 Bengi Semerci3

1Department of Psychiatry, Medical Park Gaziosmanpasa Hospital, 2Department of Psychiatry, Boylam Psychiatry Institute, 3Department of Psychiatry, Bengi Semerci Institute, Istanbul, Turkey

Objective: Although adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often persists beyond childhood, daily clinical practices and transition of adult patients with ADHD into adult mental health services in Turkey are not well studied. The aim of this study was to provide data about the presentation of adult patients with ADHD and evaluate the treatment strategies of Turkish adult psychiatrists based on their personal clinical experience in different hospital settings.

Methods: A cross-sectional online survey to be filled out by Turkish adult psychiatrists was designed and administered in May 2014. The survey focused on the treatment environment, patterns of patient applications and transition, treatment strategies, and medication management for adults with ADHD.

Results: Significant differences were observed in the number of adult patients with ADHD in follow up, and a significant positive correlation was found between number of adult patients with ADHD in follow up and the clinician’s opinion about their level of self-competence to treat adult ADHD. A significant portion of adult psychiatrists have not received any information about their adult ADHD patients’ treatment during childhood. The most preferred medical treatment was stimulants and the majority of the participants always preferred psychoeducation in addition to medication treatment. A majority of participants did not define themselves competent enough to treat and follow up adult patients with ADHD.

Conclusion: The findings of this study indicate the need to increase the knowledge, skills, and awareness of adult psychiatrists about adult ADHD. In addition, a more collaborative working relationship between child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists with a definite transition policy is required in order to help patients with ADHD more effectively.

Keywords: attention deficit hyperactivity disorders, transition, treatment strategies

Objective

Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is an extremely debilitating neurodevelopmental disorder that often persists beyond childhood, affecting 2.5%–5% of adults in the general population.1 It is one of the most frequent psychiatric disorders that affect the childhood population, and recent data suggest that the diagnosis persists in the adult age in 15%–65% of the cases.2 In the National Comorbidity Survey, the prevalence rate of ADHD in 3,199 respondents of age 18–44 years was reported to be 4.4%.3 Similarly, in the study of WHO that was carried out in ten countries in the US, Europe, and the Middle East with 11,422 patients who were 18–44 years old, estimates of ADHD prevalence averaged 3.4% (range 1.2%–7.3%).4

In Turkey, epidemiological studies about the prevalence of ADHD are limited and mostly conducted with psychiatry outpatients or special populations. In a study carried out at Istanbul University, the prevalence of ADHD in adult psychiatric outpatient clinic was found to be at least 1.6% among 850 adult outpatients.5

Most adults with ADHD predominantly exhibit problems with distraction, which manifest as forgetfulness, disorganization, difficulty in planning, task completion, and time management. These symptoms have great impact on functioning in daily life, with substantial impairments in work, social life, and relationships.6,7 The results of previous studies suggest that ADHD in adults is associated with relatively specific risks for disruptive behavior disorders, school and job performance problems, and driving risks. Individuals with ADHD miss significantly more days of work and are more likely to be fired, change jobs, and have worse job performance evaluations than those without ADHD. These situations can adversely affect productivity as measured by income loss and cost to the economy.8,9 Adults with ADHD are also known to be at increased risk for antisocial behavior, substance abuse, and criminal activity. Furthermore, they often have comorbid psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.10–12 The impact of ADHD on everyday life may diminish with age, with many patients developing effective coping mechanisms; nevertheless, ADHD often remains an impairing condition and it still continues to be an underdiagnosed disorder in adults.13 Because the current diagnostic criteria for ADHD were developed when the disease was assumed to be exclusively a childhood disorder, the criteria may not be applicable to the adult manifestation of ADHD. Additionally, adults frequently suffer from a range of comorbid conditions, which may further complicate the diagnosis.14 Although awareness and recognition of ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults have improved in recent years, there are still concerns that an interruption in the clinical management of this disorder occurs while transitioning patients into adult mental health services.15 According to the outcomes of a survey study, ADHD in the adult age is a less defined clinical entity the diagnosis of which is not as clear when compared to that occurring in childhood and adolescence, and adult ADHD is less adequately treated than in childhood and adolescence. The results of the survey were interpreted as suggesting that professionals may be more reluctant to diagnose and treat ADHD in the adult age.16

Despite the presence of a rapidly expanding literature on the importance of diagnosing and treating ADHD in adulthood, clinical experience and attitudes of the specialists in the context of adult ADHD and transition of the patients into adult mental health services in Turkey are not well studied.17 The aim of this study was to provide data about the presentation of adult ADHD in clinical practice in Turkey and the treatment strategies of Turkish adult psychiatrists based on their personal clinical experience in different hospital settings.

Methods

Procedure

A cross-sectional online survey to be filled out by Turkish adult psychiatrists was designed in May 2014. With the aim of reaching respondents in a large geographical area, an internet-based, self-report survey was administered utilizing software developed by Survey Monkey (http://www.surveymonkey.com/). Turkish adult psychiatrists were invited to participate in the survey via an email that was administered through Turkish Psychiatry Association mail group that covers >90% of Turkish adult psychiatrists’ population all over the country. Online survey link was attached to the survey invitation mail, and adult psychiatrists who accepted the invitation filled out the online survey.

The survey instrument

The survey had three main parts with 13 questions, focusing on the treatment environment, patterns of patient applications and transition, treatment strategies, and medication management for adults with ADHD. The first part of the survey refers to the clinicians’ working place, the number of patients treated daily in total, and the number of adult patients with ADHD in follow up. The second part of the survey involves questions about applications and referrals of patients with ADHD to adult mental health services. The third part of the survey includes questions about comorbidity and different aspects of treatment (the clinician’s preference on treatment, follow up duration, and treatment adherence). One question specifically refers to the clinician’s opinion about his/her self-competence to treat adult ADHD in terms of their knowledge and clinical practice. Due to the characteristics of the study, evaluation by the ethics committee of Medical Park Gaziosmanpasa Hospital was not necessary. First-part questions on working environment of the physicians were single-select multiple choice questions and respondents selected one answer from the list of answer choices. Questions about the referrals of patients, comorbidity, and treatment were comparison and frequency ranking question scales.

Analyses

Descriptive analysis was conducted with the results of the qualitative variables in the form of frequency and percentages. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and multiple linear regression analysis were used to examine the relationship between the selected variables. The analyses were performed using Microsoft® Excel program for Windows.

Results

A total of 124 adult psychiatrists across all regions of Turkey personally filled out the online survey from different treatment centers. Regarding the institution, 34.6% of the psychiatrists worked in university hospitals, 15.3% at research and training hospitals, 29% at state hospitals, and 20.9% at private practice. The daily number of treated patients in total has been asked in order to understand the clinical environment and workload of psychiatrists. The results showed that only 30% of respondents treated 15 or less patients per day, but on the contrary 53% reported that they treated >21 patients in a day (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Daily number of patients treated in clinical practice. |

Significant differences were observed in relation to the question of the number of adult patients with ADHD in follow up. Approximately 58% of the clinics were following less than ten adult ADHD patients at the time the survey was conducted, whereas only 16% of clinics were following >40 adult patients with ADHD (Figure 2).

| Figure 2 Number of adult ADHD patients in follow up per physician. |

Results of the Pearson correlation coefficients analyses showed no correlation between the number of adult patients with ADHD in follow up and the psychiatrists’ workload measured by the daily treated patient (rp=−0.14 and P=0.12). On the other hand, there was a significant positive correlation between number of adult patients with ADHD in follow up and the level of self-competence to treat adult ADHD (rp=0.52 and P<0.00001). The relationship between the working environment and number of adult patients with ADHD in follow up was evaluated with multiple linear regression analysis but no significant relationship was found between the treatment centers and number of adult patients with ADHD in follow up (P=0.08).

When the data about the admission ways of adult patients with ADHD for treatment were examined, three of the ways came into prominence: guidance of the patient’s family or social milieu, individual application by gaining awareness from media channels, and referral of child and adolescent psychiatrists (Figure 3).

| Figure 3 Admission ways of adult ADHD patients for treatment. |

The survey results were significant in that 85% of the respondents stated that they have not received any information about their adult patients with ADHD from the child and adolescent psychiatrists who followed up the patients during childhood. In addition, only 18% of the adult psychiatrists stated that >50% of their patients have been treated for ADHD in childhood (Table 1).

| Table 1 Referral situation and treatment history of the adult ADHD patients during the transition into adult mental health services |

In relation to the question about treatment choice, there were significant differences in attitudes about the treatment of adult ADHD (Table 2). Rating questions were asked to survey respondents to compare treatment strategies in order of frequency. A total of 62.6% of the participants reported that they always prefer psychoeducation in addition to medication treatment, whereas only 9.59% of the participants reported that they always combine psychotherapy with medication in the treatment of adult ADHD.

| Table 2 Treatment choice of respondents for adult ADHD treatment |

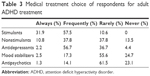

The most preferred medical treatment was stimulants (31.9% reported as using it “always” and 57.4% reported as using it “frequently”; Table 3). The other frequently preferred medications were antidepressants (56.6%) and nonstimulants (37.4%). When considering the reasons of discontinuation to treatment, there were significant differences: most of the participants were classified as nonadherent to medical treatment, which is the main reason of discontinuity and also the negative feedback from the patient’s social milieu, patients’ thoughts that the treatment is unnecessary, and prejudices about stimulant medication were other reasons.

| Table 3 Medical treatment choice of respondents for adult ADHD treatment |

Anxiety disorders have been reported as the most common comorbid disorder with adult ADHD (40.4%), followed by alcohol/substance abuse disorders (29.7%), and depression (15.9%; Figure 4).

Results of the question that evaluated the self-competence to treat adult ADHD in terms of knowledge and clinical practice, showed 85% of the clinicians surveyed did not define themselves competent enough to treat and follow up adult patients with ADHD.

Conclusion

This study sought to understand the clinical experience and the attitudes of the specialists in the context of adult ADHD in Turkey. It represents the first online survey applied to adult psychiatrists countrywide on adult ADHD. Given the impact of ADHD in adult life, it is vital that adolescents with ADHD are able to access continuing support from mental health services as they transition into adulthood.18 It turned out in our study that there are significant differences between clinics in relation to the number of adult patients with ADHD in follow up in Turkey. Although the daily number of patients treated in outpatient clinics is really high, ADHD diagnosis is not encountered as much as we expected. A previous study from Turkey showed that 75% of the adult psychiatrists were reticent or unwilling to screen for ADHD in patients with depression/anxiety and 20% of them never screen for ADHD.15 Adult ADHD seems to be a clinical entity with a lower degree of awareness even among psychiatrists compared with ADHD in childhood and adolescence.

The literature shows that treatment is prematurely discontinued in some young adults in whom symptoms persist. There are also many adults with ADHD who were never diagnosed or treated for ADHD when they were children.19 The psychiatrists may be omitting the diagnosis in adults due to the age-dependent changes in the presentation of ADHD symptoms. The more overtly impairing symptoms in childhood, hyperactivity and impulsivity, often become less obvious in adulthood, shifting the problem to more subtle symptoms such as inner restlessness, inattention, disorganization, and to other executive function difficulties in the impairments related to the demands of adult life. ADHD in adults should therefore be judged with reference to developmentally appropriate norms.20 Furthermore, adults may be more successful at hiding or compensating their symptoms in order to escape the stigma of having a psychiatric disorder than children. A diagnosis based only on self-report can also lead to underdiagnosis of adult ADHD; retrospective recall of childhood symptoms may be compromised in adults with ADHD due to difficulties with accurate recall.21 Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders such as mood, anxiety, sleep, substance use disorders, and personality disorders may also complicate the diagnosis.

There is also a solid reality that in Turkey psychiatrists working on adult ADHD are still few and there is a lack of confidence in dealing with adult ADHD. Our results showed that 85% of the clinicians surveyed themselves competent enough to treat and follow up adult patients with ADHD. The psychiatrists working on adult ADHD may perceive themselves as not equipped enough to diagnose and treat ADHD due to the lack of standardized training programs and clear guidelines for adults. While several national psychiatry organizations, including the Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance, the National Institutes of Health, and the British Association for Psychopharmacology, have developed practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of adults with ADHD, none of the Turkish psychiatry associations, including Turkish Psychiatry Association, Turkish Psychopharmacology Association, developed a treatment guideline for adult ADHD treatment. Until recent years, ADHD has been accepted as a childhood disorder, which can be another reason for adult psychiatrists not to think about the diagnosis. Adult psychiatrists may be reluctant to prescribe the medications because of the perceived risk of abuse and addiction of especially stimulant drugs.2,15 Despite concerns, research shows that stimulant treatment does not increase the risk of substance use disorders in adolescents or adults with ADHD but rather effective treatment of ADHD may reduce the development of substance use disorders.22–24

This study is the first to evaluate the admission ways and transition of adult patients with ADHD into adult mental health services in Turkey. Our findings indicate that in Turkey the media and the restraint of social milieu turned up to be effective factors for treatment application in adults. As we know, there is no published research about the transition of ADHD patients into adult services in Turkey. In a recent study that audited the transition of ADHD patients in England, it was found that a high percentage of young people eligible for transition (73%) were discharged or lost during follow up.25 Similarly, our results show that a very low percentage of patients who were diagnosed at childhood are being referred to adult psychiatrists without any informative instruction and unfortunately there is no transition policy formed between child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists. In addition, national electronic health record systems are still under development and there is lack of available and usable patient data for clinicians in Turkey. This situation is also limiting the follow up of the ADHD patients in health care system. Furthermore, ADHD medications licensed for adults are involved neither in government mandatory reimbursement formulary nor in private insurance companies reimbursement formulary in Turkey. As a result of this, young patients may have difficulty to reach the fundamental treatment and follow up.

In terms of treatment, stimulants are by far the best-studied and most effective treatment for ADHD, and the NICE guidelines recommend stimulants as the usual first-line treatment for adults with ADHD.26 Our findings indicate that stimulants and antidepressants are the most preferred choice of medication in daily clinic of participant clinicians. Psychological treatments should have an important place in the treatment of adults considering how the priorities, responsibilities, and interpersonal relations change within the daily life of an adult. Our results showed that psychoeducation, which is an important part of the treatment that helps the patient and his/her family to give meaning to symptoms and get awareness about the disorder and its impact, seems to be a more embraced treatment than psychotherapy in treatment attitudes of adult psychiatrists. Psychotherapy is suggested as an adjunctive treatment for adult ADHD, targeting the impairments associated with ADHD such as comorbidities, low self-esteem, relationship, and work problems.21 In a recent review, improvements in ADHD symptomatology and associated symptoms have been reported after psychotherapeutic treatment.27

This study has some limitations that have to be pointed out. The low response rate (6.4% of psychiatrists practicing in Turkey) and the self-reported online survey nature of the study allow us to discuss attitudes of the psychiatrist instead of general ADHD treatment strategies. Although treatment environment was included in the survey, educational level or specialization information of the psychiatrists was not included. However, educational level for ADHD management has been evaluated by self-competence while there is no official subspecialization of psychiatrists in Turkey.

ADHD is a psychiatric disorder that causes significant levels of impairment in multiple domains of an adult’s life. Because of this, early recognition, diagnosis, sufficient treatment, and follow up are important for adult ADHD. The findings from this survey indicate the need for standardized training programs to increase the knowledge, skills, and awareness of adult psychiatrists about adult ADHD. It is also clear that a more collaborative working relationship between child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists with a definite transition policy is required in order to help young people reach health services more effectively.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results of this study have been presented in Turkish Association for Psychopharmacology’s Seventh International Congress on Psychopharmacology & Third International Symposium on Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology (Seventh ICP to Third ISCAP) in 2015.28

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Ginsberg Y, Quintero J, Anand E, Casillas M, Upadhyaya HP. Underdiagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adult patients: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(3). | ||

Kooij SJ, Bejerot S, Blackwell A, et al. European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):67. | ||

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:716–723. | ||

Fayyad J, De Graaf R, Kessler R, et al. Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190(5):402–409. | ||

Özdemiroğlu AF, Yargıç İ, Oşaz S. Genel Psikiyatri Polikliniğinde Erişkin Dikkat Eksikliği- Hiperaktivite Bozukluğu Sıklığı ve Dikkat Eksikliği-Hiperaktivite Bozukluğuna Eşlik Eden Diğer Psikiyatrik Bozukluklar [Prevalence of ADHD in Adult Psychiatric Outpatient Clinic and Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in ADHD]. Nöropsikiyatri Arşivi. 2011;48:119–124. Turkish. | ||

Rosler M, Casas M, Konofal E, Buitelaar J. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(5):684–698. | ||

Das D, Cherbuin N, Butterworth P, Anstey KJ, Easteal S. A population-based study of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and associated impairment in middle-aged adults. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31500. | ||

Murphy K, Barkley RA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults: comorbidities and adaptive impairments. Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37(6):393–401. | ||

Biederman J, Faraone SV. The effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on employment and household income. MedGenMed. 2006;8(3):12. | ||

Knecht C, de Alvaro R, Martinez-Raga J, Balanza-Martinez V. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), substance use disorders, and criminality: a difficult problem with complex solutions. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;27(2):163–175. | ||

Mao AR, Findling RL. Comorbidities in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a practical guide to diagnosis in primary care. Postgrad Med. 2014;126(5):42–51. | ||

Aksoy UM, Aksoy SG, Akpinar A, Maner F. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms and Adult ADHD diagnosis in adult men with cannabis dependence. Healthmed. 2012;6(6):1925–1929. | ||

Pitts M, Mangle L, Asherson P. Impairments, diagnosis and treatments associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in UK adults: results from the lifetime impairment survey. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29:56–63. | ||

Kooij JJ, Huss M, Asherson P, et al. Distinguishing comorbidity and successful management of adult ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(suppl 5):3S–19S. | ||

Hall CL, Newell K, Taylor J, Sayal K, Swift KD, Hollis C. ‘Mind the gap’-mapping services for young people with ADHD transitioning from child to adult mental health services. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):186. | ||

Quintero J, Balanza-Martinez V, Correas J, Soler B, GEDA-A G. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the adult patients: view of the clinician. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2013;41(3):185–195. | ||

Weiss MD, Weiss JR. A guide to the treatment of adults with ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 3):27–37. | ||

Tufan AE, Yalug I. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a review of Turkish data. Anatolian J Psychiatry. 2010;11(4):351–359. | ||

Aksoy UM, Baysal OD, Aksoy SD, et al. Attitudes of psychiatrists towards the diagnosis and treatment of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder in adults: a survey from Turkey. Nobel Med. 2015;11(3):28–32. | ||

McCarthy S, Asherson P, Coghill D. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: treatment discontinuation in adolescents and young adults. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):273–277. | ||

Brown TE. Attention-Deficit Disorders and Comorbidities in Children, Adolescents, and Adults. Arlington, TX: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2000. | ||

Faraone SV, Upadhyaya HP. The effect of stimulant treatment for ADHD on later substance abuse and the potential for medication misuse, abuse, and diversion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):e28. | ||

Wilson JJ, Levin FR. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3(6):497–506. | ||

Wilens TE, Faraone SV, Biederman J, Gunawardene S. Does stimulant therapy of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder beget later substance abuse? A meta-analytic review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):179–185. | ||

Ogundele MO, Omenaka IL. An audit of transitional care for adolescents with ADHD in a North West England district. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(suppl 1):A129. | ||

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The NICE Guideline on Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults. London: The British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2009. | ||

Philipsen A. Psychotherapy in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: implications for treatment and research. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(10):1217–1225. | ||

Semerci B, Ergil-Altin G. An online survey of Turkish psychiatrists’ attitudes and experiences regarding adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in clinical practice. Bull Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(suppl 1):S84–S85. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.