Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 8

Accountability, Italian style: how to reply to government pressure?

Authors Mauro M, Talarico G

Received 28 April 2015

Accepted for publication 13 June 2015

Published 10 September 2015 Volume 2015:8 Pages 151—156

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S87532

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Frank Papatheofanis

Marianna Mauro, Giovanna Talarico

Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Magna Græcia University of Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy

Abstract: The current paper addresses the complex issue of accountability by focusing on Italian public hospitals and teaching hospitals; it aims to analyze Italian health care organizations' strategies for responding to the pressure generated by regulations. In particular, in the last few years, Italian hospitals and teaching hospitals have been obliged to implement or improve their accountability instruments in response to a new regulation (known as the Brunetta reform, Legislative Decree number 150/2009). The Legislative Decree aims to measure and assess the results of each public administration unit in terms of efficiency of the human resources, satisfaction level of the final users, and transparency of its action. Despite the initial consensus on the necessity to make the decision process in health care visible and transparent, health care organizations find it difficult to demonstrate accountability. The present paper summarizes the evidence on the degree of compliance to the reform requirements and will allow an in-depth understanding of Italian health organizations' attitudes toward accountability. This study will help policymakers understand the degree of acceptance and application of the new reforms and assess whether the law/regulations may be effective drivers for disseminating a culture of transparency and accountability.

Keywords: transparency, Italian health care, law/regulations, compliance

Policy background

Due to citizens’ growing need for information, public administration must make recurring and continuous efforts to improve the effectiveness, quality, and efficiency of public services.

From the mid-1990s, the gradual transition of the key concepts of “new public management” to those of the public governance represented the incentive to undertake new management tools and focus on cooperation and the more direct involvement of citizens and society in collective decisions and their implementation.1–4 In this new perspective, the concepts of autonomy and empowerment, which are typical of new public management, are joined by new concepts of transparency and accountability. These concepts arise from the assumption that the mission of public organization is not limited to only the efficient production of services but also requires the existence of mechanisms of accountability between the state and communities. Such communities include not only users/consumers of services but also citizens who are interested in forming a transparent relationship with public organizations to protect their own preferences and, thus, demand that organizations give account of their choices and actions.5,6

In the context of health care, health information sharing, gradually, has become a vital part of modern health care delivery’s ability to achieve important social values, such as the right to information and freedom of choice, as well as to ensure the best quality of care.

The importance of involving patients and the public in the redesign of a patient-focused health care system has become emphasized and strengthened in different aspects of health care activity at the international level and by international health policy.7,8 Improved accountability is an element in improving health system performance: a transparent and effective use of resources is one of the intermediate goals of a health care system in the World Health Organization (WHO) framework.9

Increasing accountability and developing greater patient and public involvement are key elements in a wide variety of reform programs of health systems worldwide.10 The United Kingdom, for example, experienced, in 2010, a new policy reform individuating framework indicators, which have been designed to provide national-level accountability for the outcomes that the National Health Service (NHS) delivers. This database performs a clear role in articulating an accountability function since it provides a national-level overview of how well the NHS is performing, linking the Secretary of State for Health and NHS England, and acting as a catalyst for quality improvement throughout the NHS while encouraging changes in culture and behavior.11

The needs of the consumer (patient) in the present time, indeed, are different from those we observed and experienced in the past, as the public (patients) now wants to be more involved in health care processes. In regard to that, patient empowerment is increasingly associated with better satisfaction, concordance with treatment, and improved health outcomes.12

Respect for a patient’s individual autonomy is an accepted principle in modern medicine. In the past half century, the concept of autonomy has usurped medical paternalism in almost all of its forms, with the intent to promote patients from passive recipients of care to partners in planning their own treatment.13 Now the concept has extended beyond individual autonomy to an expectation of empowerment at the population level, as well as in terms of involvement in aspects that go far beyond the medical sphere. The notion of patient empowerment, therefore, is reflected in the development of regulation to “encourage the involvement of citizens in redesigning the health service from the patients’ point of view”.14

In this regard, the interactivity of the Internet has had the most profound impact on needs of the patient, especially with regard to involvement, because not only is the Internet a major and facility source of health information, but it can improve patients’ understanding of their medical condition and their self-efficacy and can empower them to make health decisions and to talk to their physician, resulting in a more patient-centered interaction between patient and health professional.15

Additionally, the greater need for involvement has been induced by several societal developments, which have had an impact on the strengthening of patients’ positions, in, for example, demographic variables (young and better-educated patients prefer a more active role in decision making), a patient’s experience of illness and medical care, the type of decision they need to make, the amount of knowledge they have acquired about their condition, their attitude toward involvement, and the interactions and relationships they experience with health professionals.16

The effects of the need to involve patients and the public in the redesign of an health care system can be traced along the following two dimensions: 1) on the one hand, the emphasis on objectives and results has led to the inevitable use of complex and elaborate indicator systems aimed at monitoring performance and results and 2) on the other hand, the need to strengthen providers’ accountability to citizens has determined the enactment of policies to encourage (and make mandatory) the transparency of service providers.

Italian hospitals (Hs) and teaching Hs (THs) have been obliged to implement or improve their accountability instruments in response to a new regulation (known as the Brunetta reform, Legislative Decree number 150/2009).17 After 4 years from the enactment of the reform, we can state that a process of adaptation to the transparency regime has at least been started. Despite the progress, some problematic aspects remain, as follows: placed in front of a multiplicity of publication requirements, health care organizations (HOs) have focused on data that are readily available and have omitted information that requires complex activities of collecting and processing of data.

The present paper reports on the Italian HOs’ strategies for responding to the pressure generated by regulations, providing an overview of the main problems with the adoption of accountability instruments. It also summarizes evidence on the degree of compliance to the reform requirements: it is aimed to lead to an empirical understanding of the effectiveness of legislative instruments as drivers for disseminating a culture of transparency and accountability.

Content of reform: provisions on transparency

Transparency is one of the major principles underlying the Brunetta reform. Most of the academic literature recognizes the fundamental role of transparency and the interaction programs between citizens and public bureaucrats as the key concepts to guaranteeing a high level of accountability.18 Therefore, transparency is considered as a tool to enhance citizens’ participation and perception of services delivered and public organizations’ accountability levels.19,20

Legislative Decree number 150/2009 defines transparency as total accessibility, including through publication of information on the websites of government organizations concerning every aspect of the organization to encourage widespread forms of control.

To give full emphasis to the concept of transparency, the reform requires public administrations to establish a special section on their websites called “Transparency, evaluation and merit” (modified and labeled into “Transparent administration” by Legislative Decree number 33/2013).21

The following items, among other information, must be published within this section:

- the “Performance Plan”, which must identify the final and intermediate addresses and objectives, for a period of 3 years, assigned to the public organization and its personnel. Additionally, the plan must contain indicators of the next step of measurement and evaluation of performance;

- the “Three-year program for transparency and integrity” and its implementation status, which must indicate the initiatives that the administration plans to take to ensure an appropriate level of transparency and the initiatives aimed at the development of a culture of integrity; and

- the “Report on Performance”, which must highlight, with regard to the planned targets, results of organizational performance and individual performance achieved during the previous year and any deviations.

This information is relevant and of interest to citizens, as it allows them to effectively exert active democratic control.

In this regard, in the overall vision of the reform, citizens do not play a passive role by means of the right to inspect the work of the public organizations, but become actors with an active role, able to take part in the work of the public organizations in order to create better services that are more effective and efficient as well as a virtuous circle of successful collaboration between public and private.22 The main initiative in this respect, launched by the Italian Department of Public Administration, is called “Show Your Face”. It aims to equip the public administration with competences and tools for measuring and assessing the quality of the services provided thanks to the introduction of a methodical survey of customer satisfaction through emoticons. The mechanism allows citizens to cast their vote, choosing the appropriate emoticon which best represents the satisfaction level for the service delivered.22

This measuring tool can largely contribute to improving the relation between the citizens and the public organizations, making these latter more transparent and participatory. The assessment mechanism can easily detect the weak points of the administrative processes, identify priorities for service delivery, and improve the overall performance of the public organizations.

Monitoring and outcomes

Through an empirical evaluation that was conducted on December 31, 2013 on all Italian Hs and THs, the following research questions were examined: 1) what is the compliance rate of Italian Hs and THs to the transparency dictates of Legislative Decree number 150/2009?; 2) what are the differences between the two clusters (Hs and THs)?; and 3) what is the quality of the instruments used by Hs and THs in fulfilling the reform requirements?

To provide answers to our questions, we mixed quantitative and qualitative methods. To highlight the effective degree of consensus concerning the new regulation of Hs and THs, we measured the concentration rate, showing the percentage of organizations compliant with regulations.

In particular, we investigated the following accountability prescriptions:

- the presence of the section entitled “Transparency, Evaluation and Merit or Transparent Administration” (taking into account the changes to the denomination made by Legislative Decree number 33/2013) on the organizations’ websites; and

- the presence of the following documents in the aforementioned section:

- “Performance Plan”;

- “Three-year program for transparency and integrity”; and

- “Report on Performance”.

The objective of assessing the quality of the instruments used by Hs and THs was pursued by applying a document analysis on the “Performance Plan”, which is required by the reform. This document was selected because it is considered the instrument by which an organization identifies and addresses its strategic objectives, the indicators of the performance of the administration, and the objectives assigned to the management personnel and the related indicators.

Overall, the target population includes:

- 44 observations for the segment of Hs; and

- 33 observations for the segment of THs, with representativeness equal to 100% for both segments.

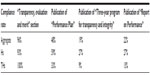

Table 1 shows a synthesis of the compliance rates of Hs and THs with regard to the transparency and accountability requirements of the Brunetta reform. Table 1 shows that HOs were compliant in regard to formal aspects, as nearly all had included a “Transparency, evaluation and merit” section on their website, in some cases with a different name: 93% of Hs and 100% of THs were compliant with the decree. Different results emerged was found with regard to the operational instruments of transparency and accountability.

| Table 1 Compliance rate of Italian hospitals and teaching hospitals for the requirements of the Brunetta reform |

The adoption of the “Performance Plan” was modest. It is the main tool of programming. As it refers to a 3-year period, it allows stakeholders to draw the line along which the organization intends to move. It identifies the objectives and measures of the evaluation of organizational and individual performance. Consistent with the “Performance Plan”, the “Three-year program for transparency and integrity” and the “Report on Performance” were written; they can be understood as the operational plans. The former defines 1) measures and means for disseminating transparency and 2) organizational actions aimed at ensuring the effectiveness and timeliness of information flow; it implements the transparency principle. The latter offers management reporting on the results achieved in the previous period, in line with the objectives defined in the programming section.

Nonetheless, the adoption of the “Three-year program for transparency and integrity” and the “Report on Performance” was very limited. Italian HOs gave greater importance to preventive detection of objectives than the identification of operational tools and reporting. Thus, they were formally compliant with the transparency requirements, by identifying objectives, but they did not individuate or communicate the tools to achieve the requirements or the results achieved. Moreover, of the 15 HOs that had published the “Three-year program for transparency and integrity”, 13 adopted the program over a period of 3 years (2013–2015), while two adopted the program for a period of 1 year.

The second and final step was to investigate the quality of the instruments provided by the HOs in fulfilling the requirements of the reform to assess whether this provision was only a mere formality or if the reform intervention was, limited to the scope of our observation, an effective driver for an administrative culture centered on the logic of transparency, participation, and accountability to stakeholders. This objective was pursued through a document analysis of the published “Performance Plan”.

The start of the document analysis process concerned the presence of a series of elements in the “Performance Plan”, as prescribed by the decree 150/2009, concerning the measurement and evaluation of organizational performance and individual performance.

As regards the measurement and evaluation of organizational performance, the results show that 97% of the 37 HOs that had drafted the plan defined the strategic objectives, while one did not provide any explicit strategic objectives within the document.

Of the 36 HOs that had defined strategic objectives in the plan, 31 (84%) had also defined the operational objectives. By contrast, 16% of HOs did not provide any definition or identification of operational objectives within the document.

With regard to the identification of the operational objectives within the plan, 78% had also defined indicators for each objective assigned, and 59% had also defined the expected result (target) for each objective.

The analysis found that organizations failed to connect the assigned objectives and allocation of resources, understood in terms of the association of human and financial resources to the strategic objectives in the “Performance Plan”. None of the HOs expressly conducted the above link.

The analysis of the documents showed that, with regard to the management and staff personnel who were responsible, the following results emerged:

- seven HOs had a system of measurement and evaluation of individual performance, although three cases described the system but did not describe the objectives assigned; and

- only three of these HOs had identified the indicators of each objective assigned to the staff and managers who were responsible.

As far as the staff who were not responsible, the following results emerged:

- three HOs had a system of measurement and evaluation of individual performance, although two cases described the system but did not describe the objectives assigned; and

- of these, only one had identified the indicators of each objective assigned to the staff who were not responsible.

The document analysis confirmed that Italian Hs and THs individuated organizational objectives, but the link between the assigned objectives and allocation of resources was completely lacking.

Based on document analysis conducted and limited to the sample, it seems that the instruments of accountability have been perceived as a requirement to fulfill rather than as tools that can drive the organization. This conclusion, in any case, needs to be strengthened and deepened by subsequent investigations.

This result was also confirmed by the data on individual performance. The section on individual performance was absent from 81% of the “Performance Plans” analyzed. In fact, the definition of a system of individual performance implies the definition of very specific actions and measures, which all stakeholders can monitor. Presumably, the management did not guarantee compliance with the cycle of performance: it only elaborated and communicated documents that were useful in becoming formally compliant with the regulations.

Conclusion

The current research shows that the logic of accountability introduced with the enactment of the reform did not reach satisfactory levels. The study, in fact, highlights the significant degree of experimentation that continues to characterize the cycle of performance management in the Italian HOs included in our observation.

In particular, the analyzed HOs are not yet able to ensure full transparency in every stage of the cycle of performance management. The level of publication of certain documents related to the implementation of the decree 150/2009 is good, albeit with a few exceptions. However, the data related to the quality of the instruments prepared are decidedly less encouraging due to lack in them of some elements, provided by the decree number 150/2009, taken as a reference to assess the quality of documents. With few exceptions, therefore, the data reporting of individual performance displays the most obvious delays in the policy of transparency and accountability of the reform in the health sector. The low levels reflect, probably, the difficulties encountered by HOs in developing the information that is required of them with the appropriate methodological and technical support. This is because any reform, even if perfect on paper, alone is not enough to generate the desired results. First, so that reform can achieve fully the expected results, it is necessary that public health managers rediscover their role and their fundamental managerial function. Second, it is necessary to implement measures and forms of accompaniment to the reform. Last, but not least, pressure from the citizens (careful and aware) is also necessary. These three elements must not only coexist, but above all be balanced and operate in a synergistic way.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Osborne SP, editor. The New Public Governance? Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance. New York: Routledge; 2010. | |

European health care reform. Analysis of current strategies. World Health Organization. WHO Reg Publ Eur Ser. 1997; 72:1–38. | |

Hood C. The “new public management” in the 1980s: variation on a theme. Accounting, Organizations and Society. 1995;20(2–3):93–109. | |

Hood C. A public management for all seasons? Public Administration. 1991;69(1):3–19. | |

Bovens M. Two concepts of accountability: accountability as a virtue and as a mechanism. West Eur Polit. 2010;33(5):946–967. | |

Wollmann H, Schröter E, editors. Comparing Public Sector Reform in Britain and Germany. Aldershot: Ashgate; 2000. | |

Coulter A, McGee H, editors. The European Patient of the Future. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2003. | |

Staniszewska S, Jones N, Newburn M, Marshall S. User involvement in the development of a research bid: barriers, enablers and impacts. Health Expect. 2007;10:173–183. | |

Shakarishvili G, Atun R, Berman P, Hsiao W, Burgess C, Lansang MA. Converging health systems frameworks: towards a concepts-to-actions roadmap for health systems strengthening in low and middle income countries. Glob Health Gov. 2010;3(2). | |

Ocloo JE, Fulop NJ. Developing a ‘critical’ approach to patient and public involvement in patient safety in the NHS: learning lessons from other parts of the public sector? Health Expect. 2012;15(4):424–432. | |

Tello J, Baez-Camargo C, editors. Strengthening Health System Accountability: A WHO European Region Multi-country Study. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. | |

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796–804. | |

Mason JK, Laurie GT. Mason and McCall Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics. 9th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. | |

Department of Health. The NHS Plan: A Plan for Investment, a Plan for Reform. The Stationery Office; 2000. | |

McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(1):24–28. | |

Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R. Patients’ preference for involvement in medical decision making: a narrative review. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(2):102–114. | |

Legislative Decree n. 150/2009. Implementation of the Law n. 15/2009, on the Optimization of the Productivity of Public Labor and Efficiency and Transparency in Public Administrations. Available from http://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo. Accessed November 10, 2009. | |

Heald D. Varieties of transparency. In: Hood C, Heald D, editors. Transparency: The Key to Better Governance? British Academy; Oxford. 2006: 25–43. | |

Ball C. What is transparency? Public Integrity. 2009;11(4):293–308. | |

Matei L, Lazar CG. Quality management and the reform of public administration in several states in South-Eastern Europe. Comparative analysis. Theoretical and Applied Economics. 2011;18(4):65–98. | |

Legislative Decree n. 33/2013. Reorganized the Rules Concerning the Obligations of Publicity, Transparency and Dissemination of Information by Public Administrations. Available from http://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo. Accessed March 14, 2014. | |

Amici M, Meneguzzo M, Matei L, Mititelu C. Evaluation and transparency in PA modernization: monitoring the main mechanisms in Italy and Romania. National and European Values of Public Administration in the Balkans. Economica Publishing House. Bucharest. 2011:123–131. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.