Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 11

A Role-Playing Activity for Medical Students Demonstrates Economic Factors Affecting Health in Underprivileged Communities

Authors Loyola AB , Palileo-Villanueva LM

Received 25 April 2020

Accepted for publication 3 August 2020

Published 9 September 2020 Volume 2020:11 Pages 637—644

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S259032

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Aldrin B Loyola, Lia M Palileo-Villanueva

Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines – Manila, Manila, Philippines

Correspondence: Aldrin B Loyola

Department of Medicine, University of the Philippines – Manila, 547 Pedro Gil Street, Ermita, Manila 1000, Philippines

Tel +632-85548400 ext. 2057

Fax +632-85260371

Email [email protected]

Background: Innovative teaching-learning strategies are necessary to promote community orientation and foster awareness of the social determinants of health among millennial learners in the health professions.

Methods: The authors designed a role-playing simulation activity that aims to highlight the multidimensional nature of health and develop in students an appreciation of the day-to-day experiences of underserved populations. The current investigation aimed to evaluate the utility of the role-playing activity and guided reflection in terms of the students’ appreciation of economic factors that affect health and health-seeking behavior of patients and their recognition of the role of healthcare professionals with respect to issues related to poverty and health. Thematic analyses of the insights and observations of the students immediately after the activity and the anonymized reflection papers were done to identify recurring ideas that made an impression on them.

Results: The students were able to identify that in a setting with limited employment opportunities and low-income potential, the residents prioritized food and shelter over everything else. They also chose cheaper products over healthier options. Practically everyone forewent out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in order to minimize its disruptive consequences. In these settings, the students highlighted the role of society and government in the provision of services and in community development. The students also emphasized the necessity for competition among a number of providers of goods and services to reduce prices. When asked if healthcare professionals are contributing to the widening gap between rich and poor, 70% agreed, 9% disagreed, 14% did not give a direct answer, and 7% said that healthcare professionals contributed in some ways and alleviated in other ways. The most commonly cited behavior that contribute to this disparity are the decision to seek highly specialized training, the congregation of practitioners in highly urbanized centers, and inattention to the economic difficulties of most patients. Those who disagreed with the statement cited systemic problems as the driving force that widens the disparity. In particular, these students cited the commodification of healthcare and related services, inappropriate policies, and insufficient funding specifically for services and health human resources.

Conclusion: The evolving landscape in healthcare financing requires more preparation among our medical students and trainees. Innovative strategies such as role-playing activities and guided reflection are useful in demonstrating economic factors that influence health and promote better understanding of externalities that shape the health status of individuals and communities.

Keywords: education, teaching, simulation training, social determinants of health

Background

Medical education has been disease oriented rather than population- or even community-oriented since the early part of the twentieth century after Abraham Flexner1 published his report on medical education in the US and Canada. The Flexner model of medical education consisting of two years of basic science followed by another two years of clinical training has been followed by leading institutions of higher learning. A review of a century of the Flexner model reveals:

… poor connections between formal knowledge and experiential learning; inadequate attention to patient populations, healthcare delivery, patient safety, and quality improvement; lack [of] a holistic view of patient experience and [poor understanding of] the broader civic and advocacy roles of physicians [among medical students].2

The under appreciation among learners of the social responsibility that underpins the career of healthcare professionals is particularly alarming. A longitudinal study of medical students shows a declining commitment to minister to the underserved as they progress with their training.3

It is important to include lessons on the social determinants of health in the curriculum of health professionals to generate awareness of possible causes of health inequities and to spark an interest in finding solutions for these among students.4 Conducting community-oriented learning activities within the medical curriculum is a challenging but necessary undertaking to emphasize the multiple dimensions of health.5,6

Training millennial students in the health professions is also particularly challenging because of their learning style. While it is very easy for this digital generation to search for content-based answers, they need guidance, direction, and deliberation in order to accomplish more complex thought processes that will deepen understanding and foster critical thinking.7 Millennial trainees prefer less formality in the learning environment, enjoy a variety of training approaches especially experiential and kinesthetic learning strategies, and value the relevance and application of information more than the acquisition of data.8 It is necessary to develop innovative teaching-learning activities to promote community orientation and foster awareness of the social determinants of health among millennial students in the health professions.

We undertook a comprehensive literature search in PubMed, Mededportal, and Google Scholar. Although we found several papers that describe educational activities to teach social determinants of health to health profession students, many of these involved online or video modules, case discussions, field exposure, service learning, or promoted a longitudinal design.9–13 We also found one paper that describes an educational activity that used a commercially available poverty simulation kit and hospital and community volunteers to role-play various resource providers in the community which was conducted among residents in training, not medical students.14

The addition of game elements in educational activities was shown to increase motivation and engagement especially among millennial students.15–17 However, reviews of gamification as an adjunct to teaching students in the health professions has not been conclusively shown to enhance learning.18,19

With these in mind, we designed “Costs, Choices, and Consequences,” an instructional strategy that combines elements of gamification, simulation, and role-play in a classroom activity. This activity allows medical students to vicariously experience the day-to-day life of poor households in the community by simulating earning, budgeting, and spending in these families in the context of life events such as births, illnesses, and catastrophes. During the activity, students are randomly divided into groups of 4 to 5 students each, with each group assigned as either a low-income family unit or merchants. The family units are tasked to complete a puzzle within a set time limit, for which they are “paid” a wage, depending on the degree of completion of the puzzle. They are then asked to make a household budget for the amount they earned, after which they purchase goods from the merchants using only the money they had earned from completing the puzzle. A different scenario (a family member gets sick and cannot work thus cannot help in completing the puzzle; a new baby is born to the family; a natural calamity) is played out for every cycle which represents one week of life, and the groups are expected to adjust accordingly. At the end of 4 to 5 cycles, the groups are given 10 to 15 minutes to discuss their insights within the group, after which a plenary debriefing is done using meta-cards. Each student is required to submit a reflection paper on the role of healthcare professionals (HCPs) on the issue of poverty and health one week after the activity. The entire activity takes approximately 3 hours: 30 minutes to introduce the activity and organize the students into groups; 1.5 hours for the simulation game; and 1 hour for debriefing and conclusion.

We conducted this activity among third-year medical students at the beginning of their Internal Medicine ambulatory course. During this module, students regularly interact with indigent patients consulting at the outpatient clinics of a tertiary government hospital. We felt it was important to develop in our students an appreciation of the day-to-day experiences of the poor and underserved to set the tone for their actual patient encounters. We hoped that through this activity, our students would realize the impact of various external factors, particularly social and economic determinants, on health, and allow them to more effectively engage with and manage the patients they would encounter in the future.

As of the writing of this paper, a total of 312 students had participated in Costs, Choices, and Consequences. We describe the students’ appreciation of the economic factors that affect health and health-seeking behavior of patients, and the role of HCPs with respect to the issue of poverty and health, and their perceptions of and satisfaction with the activity.

Methods

This study was submitted to the University of the Philippines – Manila Research Ethics Board for approval. It was deemed exempted from ethics review because the study involved the analysis of previously submitted class assignments that were anonymized. Nevertheless, we informed all the students whose personal reflection papers were eligible for analysis about the study to give them an opportunity to have their papers excluded from the study.

We undertook a thematic analysis of the anonymized meta-cards, which the students used to summarize their insights and observations during the debriefing at the end of the activity. We identified recurring ideas that made an impression on the students.

Two independent research assistants analyzed the anonymized reflection papers using the Grounded Theory approach.20 Open coding was done, and themes were agreed upon by discussion and consensus among the investigators. The feedback of the students was collated to determine the acceptability of the activity as well as the students’ satisfaction with the learning experience.

We also analyzed the course evaluation by students for the subject to determine the impact of this activity on the overall evaluation of the course by the students.

Results

We conducted 16 sessions of the activity with a total of 312 students from AY 2014–15 and AY 2015–16.

Economic Factors Affecting Health

The following themes were gleaned from the review of the meta-cards used during the debriefing after each activity:

- Capitalism is an economic system based on private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Monopolies often lead to higher prices for goods in contrast to a competitive market. A combination of these two is detrimental to consumers because product scarcity can be manipulated resulting in higher costs. In theory, in a perfectly competitive market, price is dictated by supply and demand.

- With limited resources, people tend to sacrifice their own health by choosing cheaper goods over products with better quality. They may even resort to desperate measures for their survival (eg, shoplifting).

- The larger the family size, the harder it is to allocate a small budget. The demand for resources increases as the family grows and if any member contracts illness, there will be additional constraints imposed on the available resources.

- Homemakers who are not earning often feel dissatisfied because they are unable to contribute financially to the family.

- Saving and setting priorities for long-term goals are important but are often neglected because families with limited resources are overwhelmed merely trying to survive on a daily basis.

- Contingency planning for unexpected crises is a luxury most poor families are unable to afford.

- Out-of-pocket health expenditure is costly, disrupts family dynamics, and can impoverish an entire household.

- Sharing and cooperation between family members is necessary to resolve living and health issues.

- Government’s responsibility to protect and advance the interests of society includes the delivery of affordable, high-quality health care.

Role of HCPs in Addressing Poverty

A total of 311 reflection papers were analyzed; one student opted to exclude the submitted reflection paper from the study.

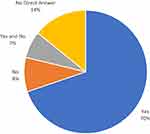

On the question, if HCPs are contributing to the widening gap between rich and poor, 217 out of 311 (70%) said that HCPs are contributing to the increasing disparity, followed by no direct answer with 44 essays (14%). These results are then followed by 28 essays (9%) which said that HCPs are not contributing to the disparity, and lastly 22 essays (7%) which said that HCPs are both contributing and not contributing to the widening gap between the rich and the poor (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Student’s response to the question “Are healthcare professionals contributing to the widening gap between rich and poor?”. |

The predominant themes the students identified as contributing to the widening gap between rich and poor are 1) behaviors of HCPs, 2) systemic problem, 3) work setting and choice of work location of HCPs, and 4) specialization. The different concepts associated with these themes are summarized in Table 1.

|

Table 1 HCP-Related Factors Contributing to the Increasing Gap Between Rich and Poor |

On the question of how HCPs can help alleviate poverty, the students acknowledged that there are things that can be improved for the healthcare system to better serve the needs of the country. The themes that emerged upon analyzing the concepts pertaining to this question are (1) holistic approach to healthcare provision, (2) advocacy and social action of HCPs on critical issues affecting health, (3) emphasis on preventive health care, and (4) engagement in relevant research and education. The different concepts associated with these themes are summarized in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Means for HCPs to Help in Poverty Alleviation |

Satisfaction with the Activity

All the students said they enjoyed the activity in their reflection papers. In the student evaluation of the course at the end of their clinical rotation, students cited the role-playing activity as a significant learning experience contributing to their training as health managers and/or leaders, as social mobilizers, and as patient advocates. The activity was also perceived to be promoting community orientation among medical students.

Discussion

The experiential instructional strategy was effective in engaging millennial students.8 As shown in the evaluation of the role-playing activity for medical students described in this paper, they were able to identify important factors related to economic issues during the processing of the vicarious experience right after the activity. In order to reinforce this learning, guided reflection was also a useful tool.7 The students also found the activity quite enjoyable because of the relaxed atmosphere and the collaborative activities during the role-playing and during the processing session. The role-playing activity and the guided reflection were able to consolidate learning and challenged the students to look for associations between the behavior of HCPs and health inequities and to recommend solutions to these problems.

In order to better understand the current situation of medical doctors and students, it would be prudent to look into the historical developments that shaped the current practice of most physicians. There were two significant developments in the second half of the twentieth century that significantly altered the practice patterns of doctors. The first was the development of biomedical research that promoted the advancement of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions by leaps and bounds and the second was the evolution of clinical practice into an entrepreneurial venture.2,21 These historical developments led to unfortunate consequences for the healthcare system, the training of medical practitioners, and the public perception of HCPs.

First, rapid advancements in medical technology gave rise to highly specialized care and numerous diagnostic and therapeutic interventions which in turn led to uncontrolled inflation of healthcare expenditure. The rise of third-party medical care payment schemes and the subsequent imposition of prospective and fixed-price payment arrangements for health services pushed providers to become increasingly concerned with revenue generation and cost-cutting measures. The provision of health care was increasingly viewed as a business enterprise and health care as a product much like other commodities. On the part of the doctor, economic and professional concerns often became obscured leading to conflicts of interest that eroded public confidence in the profession.21

Our students were able to identify these sources of health disparities in the learning activity. The most common insight given by the students was capitalism as a means of production that prioritizes profit. Commercialization of healthcare as a health system concern as well as specific behaviors of HCPs that reflect conflicts of interest, choice of work location, and specialization were also identified as contributing to health inequities.

Second, biomedical technological advancements shifted research focus from clinical and bedside studies to molecular investigations. Medical schools were likewise incorporated into universities that promoted a publish or perish culture. Faculty members of medical schools found it difficult to teach and to hold clinic while doing research. On the other hand, clinical faculty found it difficult to engage in research and therefore lost their teaching appointments. The clinical training of medical students fell on residents-in-training and fellows-in-training in an inpatient environment dealing with acutely ill individuals.2

This skewed the training of medical students towards acute inpatient care with particular emphasis on the biomedical basis of illness and treatment. Patient exposure was limited to the acute phase of the disease, teaching was trimmed down to the pathophysiologic and therapeutic aspects of clinical care, mentorship was lacking, and role-modeling was limited to highly specialized training.2 With specific focus to the resolution of the acute illness and with limited guidance from more experienced clinicians and community-based practitioners, little emphasis was given to the socio-economic and environmental factors that predisposed the patient to the adverse experience and those that would facilitate or hinder adequate recovery upon discharge to the community.

There are only a few medical schools with programs that emphasize training in community health.22,23 For many medical schools very little, if any, attention is given to population and community health, social determinants of health, and sources of health inequities during clinical training.4 Further, most trainees are from urban areas and often have affluent backgrounds.24 For these reasons, many medical students are only vaguely familiar with the plight of the poor and underserved groups.25 It is necessary to deepen the understanding of medical students of the difficulties of poor populations because doctors set the trajectory of healthcare expenditure.26 Physicians also need to be well versed on issues related to stewardship of limited healthcare resources for them to achieve the best possible outcome given these constraints.27

The role-playing activity was successful in drawing the attention of students to the day to day economic difficulties of the poor: (1) limited resources, (2) desperate measures in order to survive, (3) allocating limited budget, (4) additional constraints imposed on the available resources because of illness, (5) dissatisfaction of non-earning family members, (6) disregard for long-term goals in favor of daily survival, (6) lack of preparation against unexpected crises, and (7) bankruptcy due to catastrophic health expenditure.

Our students also identified action points related to (1) holistic approach to healthcare provision, (2) advocacy and social action, (3) preventive healthcare, and (4) research and education to address inequity in health as measures to help alleviate poverty. However, students had to be reminded that there were other means to finance healthcare aside from out-of-pocket expenditure and that cooperative work and collaborative efforts were needed to achieve community development.

There is a need to incorporate topics in enterprise management in the training of medical students to emphasize the value of administrative expertise in any worthy endeavor including provision of healthcare. They must also realize that as HCPs, they are sources of information and expertise that inform policy as well as change agents who can promote, advocate, and enact positive changes in the health system.23,25,28–30

The challenge is to reinforce the experience, heighten the perception, and deepen the understanding of students in order to widen their perspective, to provoke critical thought, to cultivate a compassionate attitude towards the underserved, and to prompt decisive actions to address health inequities.5 In order to achieve these, it has been recommended to recruit students from underserved groups, underpin the curriculum with the health and social needs of target groups, carry out community-based learning strategies, integrate population health and social sciences into the basic and clinical curricula, implement service-based, community-oriented teaching methods, and enact some form of return-of-service agreement.2,24,31,32 On top of these, Irby and co-workers propose interventions to foster the formation of the students’ professional identity such as formal ethics training and encounters, alignment of the hidden curriculum with the espoused values of the institution, mentorship in professionalism, and collaborative learning directed at continuous improvement and excellence.2

The evolving landscape in healthcare financing requires more preparation among our medical students and trainees. It is no longer enough for colleges of medicine to ensure adequate training in the basic and clinical sciences. It is also important to provide our trainees with conceptual handles and tools which they can use to navigate the increasingly complex and sophisticated healthcare environment.5,33

Costs, Choices, and Consequences, an educational activity that combines elements of gamification, simulation, and role-play in a classroom activity followed by guided reflection may be an effective means to demonstrate economic factors that affect health and promote better understanding of externalities that shape the health status of individuals and communities among medical students. Further comparative studies are recommended in diverse settings and learner populations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Ferlie Famaloan and Ms. Jhaki Mendoza for assisting us with the analysis of the student essays. We would also like to thank Dr. Lance Catedral and Dr. Jhoanna Rose Velasquez for their assistance in the analysis of the meta-cards and facilitating ethics review.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada. From the Carnegie foundation for the advancement of teaching, bulletin number four, 1910. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(7):594–602.

2. Irby DM, Cooke M, O’Brien BC. Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie foundation for the advancement of teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):220–227. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c88449

3. Crandall SJ, Reboussin BA, Michielutte R, Anthony JE, Naughton MJ. Medical students’ attitudes toward underserved patients: a longitudinal comparison of problem-based and traditional medical curricula. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2007;12(1):71–86. doi:10.1007/s10459-005-2297-1

4. Doobay-Persaud A, Adler MD, Bartell TR, et al. Teaching the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):720–730. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04876-0

5. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2016.

6. Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O. Targeting health disparities: a model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):339–349. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.339

7. Roberts DH, Newman LR, Schwartzstein RM. Twelve tips for facilitating Millennials’ learning. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):274–278. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2011.613498

8. Bart M. The 5 R’s of engaging millennial students. Faculty focus; 2011. Available from: https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/the-five-rs-of-engaging-millennial-students/.

9. Potter LA, Burnett-Bowie S-AM, Potter J. Teaching medical students how to ask patients questions about identity, intersectionality, and resilience. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10422

10. Martinez IL, Ilangovan K, Whisenant EB, Pedoussaut M, Lage OG. Breast health disparities: a primer for medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10471

11. Kutscher E, Boutin-Foster C. Community perspectives in medicine: elective for first-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10501

12. Schmidt S, Higgins S, George M, Stone A, Bussey-Jones J, Dillard R. An experiential resident module for understanding social determinants of health at an academic safety-net hospital. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10647

13. Stumbar SE, Garba NA, Holder C. Let’s talk about sex: the social determinants of sexual and reproductive health for second-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10772

14. Maguire MS, Kottenhahn R, Consiglio-Ward L, Smalls A, Dressler R. Using a poverty simulation in graduate medical education as a mechanism to introduce social determinants of health and cultural competency. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):386–387. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00776.1

15. Hamari J, Koivisto J, Sarsa H Does Gamification Work? – A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification.

16. Brigham TJ. An introduction to gamification: adding game elements for engagement. Med Ref Serv Q. 2015;34(4):471–480. doi:10.1080/02763869.2015.1082385

17. Brull S, Finlayson S. Importance of gamification in increasing learning. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2016;47(8):372–375. doi:10.3928/00220124-20160715-09

18. Akl EA, Pretorius RW, Sackett K, et al. The effect of educational games on medical students’ learning outcomes: a systematic review: BEME guide no 14. Med Teach. 2010;32(1):16–27. doi:10.3109/01421590903473969

19. Gentry SV, Gauthier A, L’Estrade Ehrstrom B, et al. Serious gaming and gamification education in health professions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e12994. doi:10.2196/12994

20. Moghaddam A. Coding issues in grounded theory. J Educ Res. 2006;16(1):52–66.

21. Relman AS Medicine as a profession and a business; 1986. Available from: https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/r/relman88.pdf.

22. Duffy FD, Miller-Cribbs JE, Clancy GP, et al. Changing the culture of a medical school by orienting students and faculty toward community medicine. Acad Med. 2014;89(12):1630–1635. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000463

23. Girotti JA, Loy GL, Michel JL, Henderson VA. The urban medicine program: developing physician-leaders to serve underserved urban communities. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1658–1666. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000970

24. Murray RB, Larkins S, Russell H, Ewen S, Prideaux D. Medical schools as agents of change: socially accountable medical education. Med J Aust. 2012;196(10):653. doi:10.5694/mja11.11473

25. Doran KM, Kirley K, Barnosky AR, Williams JC, Cheng JE. Developing a novel Poverty in Healthcare curriculum for medical students at the University of Michigan Medical School. Acad Med. 2008;83(1):5–13. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31815c6791

26. Canadian Institute for Health Information. National health expenditure trends, 1975 to 2015; 2015. Available from: https://www.hhr-rhs.ca/index.php?option=com_mtree&task=att_download&link_id=11135&cf_id=68&lang=en.

27. Australian Medical Association. The role of doctors in stewardship of healthcare financing and funding arrangements; 2016. Available from: https://ama.com.au/position-statement/doctors-role-stewardship-health-care-resources-2016.

28. Oandasan IF. Health advocacy: bringing clarity to educators through the voices of physician health advocates. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S38–41. doi:10.1097/00001888-200510001-00013

29. Girgis L, Van Gurp G, Zakus D, Andermann A. Physician experiences and barriers to addressing the social determinants of health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a qualitative research study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):614. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3408-z

30. Westerhaus M, Finnegan A, Haidar M, Kleinman A, Mukherjee J, Farmer P. The necessity of social medicine in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):565–568. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000571

31. Ross SJ, Preston R, Lindemann IC, et al. The training for health equity network evaluation framework: a pilot study at five health professional schools. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2014;27(2):116–126. doi:10.4103/1357-6283.143727

32. Powell T, Garcia KA, Lopez A, Bailey J, Willies-Jacobo L. University of California San Diego’s program in medical education-health equity (PRIME-HEq): training future physicians to care for underserved communities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(3):937–946. doi:10.1353/hpu.2016.0109

33. World Health Organization. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health, Final Report. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health; 2008.

34. Department of Health. Doctors to the barrios; 1993. Available from: https://doctorstothebarrios.com/about/.

35. Department of Health. What are deployment programs? Available from: https://www.doh.gov.ph/faqs/What-are-the-deployment-programs.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.