Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 9

A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system

Authors Duenas M , Ojeda B, Salazar A , Mico JA, Failde I

Received 5 February 2016

Accepted for publication 22 April 2016

Published 28 June 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 457—467

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S105892

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Michael Schatman

María Dueñas,1 Begoña Ojeda,2 Alejandro Salazar,2 Juan Antonio Mico,3 Inmaculada Failde,2

1Nursing Faculty “Salus Infirmorum”, The Observatory of Pain, University of Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain; 2Preventive Medicine and Public Health Area, The Observatory of Pain, University of Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain; 3Department of Neuroscience, Pharmacology, and Psychiatry, CIBER of Mental Health, CIBERSAM, Institute of Health Carlos III, University of Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain

Abstract: Chronic pain (CP) seriously affects the patient’s daily activities and quality of life, but few studies on CP have considered its effects on the patient’s social and family environment. In this work, through a review of the literature, we assessed several aspects of how CP influences the patient’s daily activities and quality of life, as well as its repercussions in the workplace, and on the family and social environment. Finally, the consequences of pain on the health care system are discussed. On the basis of the results, we concluded that in addition to the serious consequences on the patient’s life, CP has a severe detrimental effect on their social and family environment, as well as on health care services. Thus, we want to emphasize on the need to adopt a multidisciplinary approach to treatment so as to obtain more comprehensive improvements for patients in familial and social contexts. Accordingly, it would be beneficial to promote more social- and family-oriented research initiatives.

Keywords: pain, everyday problems, social relationships, family environment, health services

Introduction

Chronic pain (CP) is recognized as a major public health problem, producing a significant economic and social burden.1–4 Moreover, this condition not only affects the patient (both as a sensory and emotional problem) but it also affects his/her family and social circle.5,6 The biopsychosocial model, considered essential in pain, provides a framework for understanding how different diseases are related through an assessment of sensorial, cognitive/affective, and interpersonal factors. Thus, considering this framework, it has been shown that CP is often associated with other processes that, in turn, affect pain strongly7 (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Biopsychosocial model of pain and consequences on the quality of life. |

Studies performed in different settings have demonstrated that CP affects between 10% and 30% of the adult population in Europe.1,8 Indeed, a recent study showed a 16.6% prevalence of this condition among the general population in Spain, with at least one person affected in every four Spanish homes.4 The experience of pain interferes with different aspects of the patient’s life,9 negatively affecting their daily activities, physical and mental health, family and social relationships, and their interactions in the workplace (Figure 1). This problem also affects the health care system and what is known as economic well-being,1,9–15 the strong burden associated with CP not only deriving from health care costs but also from the loss of productivity and from compensatory payments to patients as a result of the disability that pain produces.16

Despite their relevance, few studies have addressed all these aspects of CP in a comprehensive and multidimensional manner, and studies that specifically analyze the impact of pain on the family environment are scarce.

In this review, our goal was to describe the effect of CP on the individual, their family and social environment, as well as on the health care system. To achieve this, we initially address the consequences of CP on the patient’s daily activities and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), before reviewing the repercussions of CP at the workplace, and in the family and social environment. Finally, we discuss the consequences of CP on the health care system.

Methods

A search was undertaken to identify papers published between 1995 and 2014 in English and Spanish languages in the following electronic databases: Web of Knowledge, PubMed, and Science Direct. Several combinations of the following keywords were used: chronic pain, social consequences, daily problems, physical activity, quality of life, sleep, work, family, and health care system. Thus, the search terms used were: “chronic pain” AND (“social consequences” OR “daily problems” OR “physical activity” OR “quality of life” OR “sleep” OR “work” OR “family” OR “health care system”).

The selection process of the papers was based on prespecified criteria for including and excluding studies (eligibility criteria) on the basis of the aim and the methodology used. Thus, a paper was eligible only when the main aim of the study matched the topics of this review, and also only if it was a review or a cross-sectional study. To standardize the information collected, we decided to include only longitudinal studies when they provided relevant information not found in other papers. Clinical trials, studies in animal models, studies that only assessed the prevalence or the incidence of CP, or those that analyzed only risk factors were excluded.

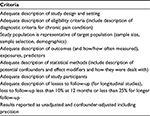

Furthermore, the quality of the studies selected was evaluated according to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist.17 This assessment conforms to a basic set of criteria related to potential sources of bias in observational studies (Table 1). A study was considered as high quality if the authors met all the criteria or missed only one criterion, medium quality if they missed two or three criteria, and low quality if they missed four or more criteria.

| Table 1 Quality criteria for the assessment of the observational studies (criteria to be answered with yes/no/unclear) |

Three of the authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the papers to identify the studies that best fulfilled the selection criteria. All duplicate items were removed using the bibliographic tool RefWorks. The references of all the studies retrieved were checked to identify any studies that had not been detected by the computerized search, a procedure that led to the inclusion of several more studies that fulfilled the selection criteria.

The most relevant information (design, participants, sample size, question relevance) was collected from each of the studies and was listed in a table along with a study’s quality details. The results of this review were summarized from included studies by classifying them according to defined questions. Rather than a systematic exhaustive approach, this review employed a narrative method to synthesize the most relevant, reliable, and recent studies about the impact of CP.

Results

A total of 78 studies were selected for this review. Of them, 68 met the criteria previously described and were included in the description of the results of this study.

Specific information for each of the papers included in the review are described in Table 2, which shows that 17 papers were valued as low quality according to the criteria used. However, seven of these lower quality studies were finally included because we felt that they provided interesting information that was addressed only scarcely in other papers.

| Table 2 Details and methodological quality of selected studies |

The effects of pain on the patient

Effects on physical function and daily activities

Several studies have analyzed the effect of CP on patient’s lives, highlighting the strong correlation between this condition and reduced physical activity.18,19 In fact, the intensity, duration, or location of pain have a decisive influence on a patient’s physical performance, diminishing their physical activity and even causing disability, which in turn affects other aspects of their daily life.20

In a study carried out on individuals with chronic back pain, the ability to perform daily activities was limited to just under a third of the individuals (31.7%),11 while elsewhere, physical deterioration was evident in 50% of patients with nononcological pain.10 In a survey across Europe,1 most individuals who experienced CP suffered different limitations, with the ability to perform intense physical exercise, walk, perform domestic chores, participate in social activities, and maintain an independent lifestyle being the activities most affected.

Similar results were also observed in other studies on specific groups of patients, such as those suffering from fibromyalgia or those with generalized pain. In these cases, the limitations experienced are more severe, with patients experiencing significant difficulty in performing essential activities, such as getting up or sitting down.21–23

It is important to note that CP patients (as opposed to pain-free individuals) are often unconscious of their level of activity, given that objective and subjective measures of their physical activity differ.24 This is interesting, since if patients overestimate their level of activity, they might feel it to be sufficient, and thus the intention or motivation to change their behavior and augment their activity would disappear.2,25 The intention or motivation to change is one of the key predictors of behavioral modifications according to the theoretical models normally employed.2 This is why making patients conscious of their behavior may ensure that they adopt a healthier lifestyle, becoming more active and diminishing the disability caused by their pain.

Effects on health-related quality of life

A patient’s quality of life, both mental and physical, is another measure of the negative repercussions of pain.9 Several studies carried out on patients with fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, or low back pain have shown that these conditions often cause a notable deterioration in the patient’s quality of life,26 each affecting the physical component of the HRQoL and with a stronger impact on the mental component of the HRQoL, particularly in fibromyalgia patients.27 Similarly, when comparing the HRQoL of acute pain and CP patients with that of pain-free individuals, CP patients achieve worse scores in all the dimensions of HRQoL compared to individuals who suffer from acute pain or have no pain.28

Some links between pain intensity and HRQoL have been defined in pain patients, demonstrating that the stronger the intensity of pain the lower the HRQoL.9,29,30 Moreover, patients with severe and frequent pain have a poorer quality of life than patients with moderate and less frequent pain, their pain having a greater impact on the physical dimensions than on the mental ones.9 Alternatively, pain intensity, symptoms of anxiety or depression, and emotion-focused coping strategies are the variables that most affected the HRQoL of fibromyalgia patients.27

Sleep disturbances are commonly experienced by CP patients, and they are closely related to HRQoL. Sleep disorders may increase levels of stress, and accordingly, such disturbances can make it difficult for patients to perform simple tasks, and they may even impair their cognitive ability, in turn affecting everyday activities in the workplace and at home.31

In a prospective study involving a group of women affected by CP,32 a bidirectional association between sleep and pain was demonstrated, whereby one night of poor sleep was followed by an increase in pain intensity the following day. Likewise, a day of greater pain intensity was followed by a night with sleep disturbances. Furthermore, when the connection between insomnia and pain levels was examined, the increase in problems caused by insomnia in a month augmented the average daily level of pain experienced in the subsequent months.33 These findings suggest that the correct diagnosis of sleep disorders and their adequate treatment are important in the management of individuals who suffer from CP, which also may be a means to improve patient’s HRQoL.

Work, social, and family-related consequences of pain

Work-related consequences

The impact of pain in the workplace is an important issue to be considered in CP patients. Studies carried out in different countries have shown that patients who are affected by pain present problems of absenteeism. Not only must they often change their occupational duties or post, but they may even end up losing their job as a result of their pain symptoms.1,12,19,34–37 In Spain, 24.4% of individuals who suffered from CP had requested sick leave in the previous year, and 12% had left or lost their job because of it.4 Moreover, when individuals with CP do not take time off from work despite being in pain, there is a reduction in their efficiency and productivity,2,25 an effect that is amplified as the intensity of pain increases.2,37 Indeed, it has been demonstrated that such presenteeism reduced productivity by 21.5% in a group of individuals with mild pain, as opposed to the individuals who suffered moderate (26%) and severe pain (42.9%) in whom these percentages were progressively higher.2

Other studies have also documented that absenteeism, presenteeism, early retirement, and disability related to CP38 present a burden at least as great as conditions that are conventionally prioritized as public health concerns.38

When the occupational consequences of different types of pain were analyzed, the processes that produced most days of sick leave are backache, followed by pain caused by rheumatic diseases.39 Neuropathic pain may also affect satisfactory performance at work and cause greater absenteeism, thereby lowering productivity and adversely affecting the ability to fulfill certain obligations. These effects on the working environment make it difficult for patients to maintain a normal lifestyle.5 Furthermore, it has been shown that a longer duration of work absenteeism is associated with poor recovery and no health benefit.40

In low back pain patients, it has been reported that, specifically in the 45- to 65-year-old age group, low back pain is one of the most frequently cited medical reasons for work loss. In addition, it has been shown that although 20% of working-age individuals seek medical help and only 20% report sickness absence related to back pain, this small percentage accounts for most of the health care costs and socioeconomic burden of these individuals.41

Similarly, it has been shown that between 43% and 78% of fibromyalgia patients are in sick leave, and the total disability status ranges between 6.7% and 30%.36,42,43 Recently, in a study carried out in Spain, it has been revealed that almost half of fibromyalgia patients had lost their capacity for work, 23% had obtained a disability pension for recognized incapacity for work status, and only 30% of them had work adaptations.44

Another important point between pain and work is the evidence that some of the relatives beliefs and behaviors appeared to pose an obstacle and impede the affected individual from returning to work.45 Thus, relatives sometimes shared and even reinforced certain feelings, such as a fear of pain or the development of a new work-related injury, and they may be pessimistic about the possibility of the patient going back to work. In some cases, family members are resigned to the negative consequences that backache has on occupational activity, and they are skeptical as to the possibility of finding a position adapted to the needs of the patient and/or a comprehensive attitude on the part of superiors. It is notable that instead of concentrating exclusively on individual risk factors associated with long-term absenteeism, it is necessary to analyze the way in which the people surrounding the patient and the social environment might contribute to the appearance or persistence of pain, as well as the consequences it produces.45 Despite its importance, this issue has received little attention in the literature to date.

Social and family-related consequences

In addition to the aforementioned consequences, CP can also affect a patient’s social interactions,46 restricting their leisure activities and social contacts. Indeed, it has been reported that half of the patients in pain indicated that their condition had prevented them from attending social or family events,47 and similarly, almost half of the individuals with pain symptoms had less contact with their family.1 Studies on patients with osteoarthritis or fibromyalgia have shown that pain as well as physical and emotional problems have a significant impact on social functioning.48,49 Likewise, a decline in physical capacity and mental health has been observed in patients with neuropathic pain, which contributes strongly to their impaired social integration. In addition, the negative emotions, irritability, and feelings of anger that often affect these patients have a negative impact on interpersonal relationships and the levels of stress in families.50 In a qualitative study carried out on neuropathic pain patients, difficulties in planning social activities in advance due to the unpredictable nature of pain were identified as the main cause of their social limitations.5

The disability produced by pain and the dependency that it often causes can also have consequences for the family and friends. To be more specific, family members often find that they need to undertake activities, such as care duties, supervision, or participation in and evaluation of treatments, and they must become involved in decision making when consulting doctors.51 As a result of these new obligations, which they often find difficult to cope with, relatives may suffer negative effects that produce a physical and psychological deterioration: feelings of sadness, being overburdened, frustration, and impotence.6,52 Indeed, the social, professional, and daily life of these family members are also greatly affected.6,46,52,53 In a recent study, it was observed that a high proportion of the relatives of CP patients suffered anxiety or sadness and that they had stopped taking part in social activities because of the presence of pain in their family.6 The suffering of a loved one due to pain has also been reported elsewhere to be an overwhelming experience for the family members who look after them,54 and often the pain or anguish that the patients suffer is felt indirectly, transformed, imagined, or distorted by caregivers, who think it is worse than it really is.

A number of studies that analyzed the impact of oncological and nononcological pain on relatives who act as caregivers also found that over 30% of the individuals surveyed admitted that they could not cope with the pain-related problems affecting their relative.55 Many of them had problems with anxiety and depression,56 and depression in the caregiver was linked to a stronger intensity of pain in the patient. It was also demonstrated that 60%–70% of those who care for patients who suffer from CP displayed one or more related pathologies54 and that the discomfort suffered by the caregiver was sometimes even greater than that reported by the patient themselves.57

Indeed, when the impact of pain from the perspective of family members and patients is compared, it is seldom concordant.57,58 Nevertheless, both groups agree that the experience of pain has harmful effects on both. In general, the existence of CP has a negative effect on the family environment, which is perceived more intensely by the relatives than by the patient, especially by family members who are caregivers.6 However, the perception of sadness in the family, mood swings, and the deterioration in leisure activities, along with sleep disturbances, all as a result of the presence of pain, are factors that both the patient and their relatives identify as having the greatest impact on the family.6

Furthermore, in a recent study,44 it has been observed that changes that occur in the lives of family members as a result of the problems in the individual with fibromyalgia are not only determinants of the family dynamics but also the degree of family satisfaction. In this sense, in this work, it has been shown that 23% of patients reported low levels of satisfaction with their family life and 59% reported many difficulties in the relationship with their partner.44

Interestingly, from a neurobiological point of view, there is a link between a person suffering from pain and impact to the environment, specifically the family or relatives. For example, some seminal findings, from Mogil’s group59 in Montreal, clearly have demonstrated that this influence might be due to a phenomenon of empathy. In fact, it seems that some central nervous system areas are implicated in this process, ie, the amygdala, the insula, and the anterior cingulate cortex. These areas are included in the “pain matrix”.60

The consequences of pain on health care systems

The impact of pain on health care systems has been addressed in several studies. There is evidence that pain constitutes an economic burden associated with considerable direct and indirect costs to health care systems and that it is one of the main reasons for medical appointments.34,58,61,62 In particular, it is responsible for considerable expenditure and consumption of resources in primary care.13,63–65 Indeed, in one study, 60% of CP patients reported that they had visited their doctor between two and nine times in the months prior to the study, and 11% had done so at least ten times.1 In addition, most of the patients (70%) went to their General Practitioner (GP), while 27% (23% in Spain) visited a specialist and only 2% were treated by a pain specialist.1 Similar results were obtained elsewhere,66 with 92.9% of the study participants having seen a health care professional at least once because of their pain symptoms, the average number of appointments in the previous year being 3.5. Again, most of them saw a GP (47.3%) or a specialist (47.7%), and only 4% were seen by a doctor in a hospital pain unit. A recent study in Portugal reported an average of six medical consultations per year among CP individuals, twice the mean seen in the general Portuguese population, and only a minority of these patients were attended to by a pain specialist.61

Very few studies have analyzed the factors linked to health care service use due to pain symptoms. Nevertheless, a greater severity and higher frequency of pain, the presence of comorbidities (physical as well as mental), and the existence of a high level of pain-related limitations and disability are factors that most strongly influence the use of health care resources by these patients.62,64,65,67 In Sweden68 and the USA,69 age, pain severity, poor self-rated health, comorbidity, psychological distress, and access to health care were the main determinants of medical visits. Likewise, in Portugal, while pain severity, affective factors, and socioeconomic determinants were the main drivers behind health care use, only the socioeconomic and affective determinants were relevant for users of nonpharmacological treatment modalities.61

It has also been reported66 that people who leave or lose their job as a result of pain, as well as those who perceive that their pain affects their family, are those that use the health care system the most. Furthermore, a number of studies have demonstrated that pain is often inadequately diagnosed and treated in primary care, with an overuse of medical appointment and health care resources. Thus, it is justified that a more specific training of professionals who work at this level of care is needed.70,71

Conclusion

CP has significant consequences for patients, as well as for their families, and their social and professional environment, causing deterioration in the quality of life of patients and those close to them. Thus, we want to emphasize the need to adopt a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to improve the patient’s condition and circumstances, contemplating both pharmacological treatments and nonpharmacological measures. To achieve this goal, it will be necessary to promote research initiatives that analyze the social factors affecting pain patients and gain information that complements clinical finding, aspects that have so far received little attention.

The assessment of the impact of pain on patients’ activities of daily living and its repercussion in the family or at work, as demonstrated in the analysis of the results presented in this review, should be especially considered as a means to improve the patient and family’s HRQoL.

The high prevalence of CP, and its serious medical and nonmedical consequences, means that those responsible for health care policies should pay particular attention to this problem. Specifically, effective health policies must be developed to prevent and manage pain, minimizing or avoiding the disability that it causes to the patient and its effects on their environment. Moreover, understanding pain as a public health priority will help to explain its close links with the social and economic aspects of health.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):287–333. | ||

Langley PC, Ruiz-Iban MA, Molina JT, De Andres J, Castellon JR. The prevalence, correlates and treatment of pain in Spain. J Med Econ. 2011;14(3):367–380. | ||

Leadley RM, Armstrong N, Lee YC, Allen A, Kleijnen J. Chronic diseases in the European Union: the prevalence and health cost implications of chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2012;26(4):310–325. | ||

Dueñas M, Salazar A, Ojeda B, et al. A nationwide study of chronic pain prevalence in the general Spanish population: identifying clinical subgroups through cluster analysis. Pain Med. 2015;16(4):811–822. | ||

Closs SJ, Staples V, Reid I, Bennett MI, Briggs M. The impact of neuropathic pain on relationships. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(2):402–411. | ||

Ojeda B, Salazar A, Dueñas M, Torres L, Micó J, Failde I. The impact of chronic pain: the perspective of patients, relatives, and caregivers. Fam Syst Heal. 2014;32(4):399–407. | ||

Scott KM, Bruffaerts R, Tsang A, et al. Depression-anxiety relationships with chronic physical conditions: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. J Affect Disord. 2007;103(1–3):113–120. | ||

Reid KJ, Harker J, Bala MM, et al. Epidemiology of chronic non-cancer pain in Europe: narrative review of prevalence, pain treatments and pain impact. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(2):449–462. | ||

Langley P, Perez Hernandez C, Margarit Ferri C, Ruiz Hidalgo D, Lubian Lopez M. Pain, health related quality of life and healthcare resource utilization in Spain. J Med Econ. 2011;14(5):628–638. | ||

Miro J, Paredes S, Rull M, et al. Pain in older adults: a prevalence study in the Mediterranean region of Catalonia. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(1):83–92. | ||

Bassols A, Bosch F, Baños JE. How does the general population treat their pain? A survey in Catalonia, Spain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(4):318–328. | ||

Blyth FM, March LM, Nicholas MK, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain, work performance and litigation. Pain. 2003;103(1–2):41–47. | ||

Langley P, Muller-Schwefe G, Nicolaou A, Liedgens H, Pergolizzi J, Varrassi G. The societal impact of pain in the European Union: health-related quality of life and healthcare resource utilization. J Med Econ. 2010;13(3):571–581. | ||

Langley PC, Molina JS, Ferri CS, P Rez Hern Ndez CN, Varillas AT, Angel Ruiz-Iban M. The association of pain with labor force participation, absenteeism, and presenteeism in Spain. J Med Econ. 2011;14(6):835–845. | ||

Smith BH, Elliott AM, Chambers WA, Smith WC, Hannaford PC, Penny K. The impact of chronic pain in the community. Fam Pract. 2001;18(3):292–299. | ||

Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Assessment of patients with chronic pain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):19–25. | ||

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. Directrices para comunicación de estudios observacionales. Gac Sanit. 2008;22(2):144–150. | ||

Lerman SF, Rudich Z, Brill S, Shalev H, Shahar G. Longitudinal associations between depression, anxiety, pain, and pain-related disability in chronic pain patients. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(3):333–341. | ||

Azevedo LF, Costa-Pereira A, Mendonca L, Dias CC, Castro-Lopes JM. Epidemiology of chronic pain: a population-based nationwide study on its prevalence, characteristics and associated disability in Portugal. J Pain. 2012;13(8):773–783. | ||

Jones J, Rutledge DN, Jones KD, Matallana L, Rooks DS. Self-assessed physical function levels of women with fibromyalgia: a national survey. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(5):406–412. | ||

McBeth J, Nicholl BI, Cordingley L, Davies KA, Macfarlane GJ. Chronic widespread pain predicts physical inactivity: results from the prospective EPIFUND study. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(9):972–979. | ||

Amris K, Wæhrens EE, Jespersen A, Bliddal H, Danneskiold-Samsøe B. Observation-based assessment of functional ability in patients with chronic widespread pain: a cross-sectional study. Pain. 2011;152(11):2470–2476. | ||

Boonen A, van den Heuvel R, van Tubergen A, et al. Large differences in cost of illness and wellbeing between patients with fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain, or ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(3):396–402. | ||

van Weering MG, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, Hermens HJ. The relationship between objectively and subjectively measured activity levels in people with chronic low back pain. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(3):256–263. | ||

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA. 2003;290(18):2443–2454. | ||

Carmona L, Ballina J, Gabriel R, Laffon A, Group ES. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the general population of Spain: results from a national survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(11):1040–1045. | ||

Campos RP, Vazquez Rodriguez MI. Health-related quality of life in women with fibromyalgia: clinical and psychological factors associated. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(2):347–355. | ||

Lopez-Silva M, Sanchez D, Rodriguez-Fernandez MC, Vazquez-Seijas E. Cavidol: quality of life and pain in primary care. Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2007;14(1):9–19. | ||

Garcia-Campayo J, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Caballero L, et al. Relationship of somatic symptoms with depression severity, quality of life, and health resources utilization in patients with major depressive disorder seeking primary health care in Spain. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(5):355–362. | ||

Davies M, Brophy S, Williams R, Taylor A. The prevalence, severity, and impact of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1518–1522. | ||

Tuzun EH. Quality of life in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(3):567–579. | ||

O’Brien EM, Waxenberg LB, Atchison JW, et al. Intraindividual variability in daily sleep and pain ratings among chronic pain patients: bidirectional association and the role of negative mood. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(5):425–433. | ||

Quartana PJ, Wickwire EM, Klick B, Grace E, Smith MT. Naturalistic changes in insomnia symptoms and pain in temporomandibular joint disorder: a cross-lagged panel analysis. Pain. 2010;149(2):325–331. | ||

Català E, Reig E, Artés M, Aliaga L, López JS, Segú JL. Prevalence of pain in the Spanish population: telephone survey in 5000 homes. Eur J Pain. 2002;6(2):133–140. | ||

Kovacs FM, Muriel A, Castillo Sanchez MD, Medina JM, Royuela A; Spanish Back Pain Research Network. Fear avoidance beliefs influence duration of sick leave in Spanish low back pain patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(16):1761–1766. | ||

Ubago Linares MC, Ruiz Perez I, Bermejo Perez MJ, Olry de Labry Lima A, Plazaola Castano J. Clinical and psychosocial characteristics of subjects with fibromyalgia. Impact of the diagnosis on patients’ activities. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2005;79(6):683–695. | ||

Patel AS, Farquharson R, Carroll D, et al. The impact and burden of chronic pain in the workplace: a qualitative systematic review. Pain Pract. 2012;12(7):578–589. | ||

Breivik H, Eisenberg E, O’Brien T; OPENMinds. The individual and societal burden of chronic pain in Europe: the case for strategic prioritisation and action to improve knowledge and availability of appropriate care. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1229. | ||

Tornero M, Atance M, Grupeli BE, Vidal F. Economic and social impact of rheumatic short-term work disability in Guadalajara. Rev Esp Reum. 1998;25(9):340–345. | ||

Costa-Black KM, Loisel P, Anema JR, Pransky G. Back pain and work. Best Pract Res Rheumatol. 2010;24(2):227–240. | ||

Watson PJ, Main CJ, Waddell G, Gales TF, Purcell-Jones G. Medically certified work loss, recurrence and costs of wage compensation for back pain: a follow-up study of the working population of Jersey. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(1):82–86. | ||

Rivera J, Gonzalez T. The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: a validated Spanish version to assess the health status in women with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22(5):554–560. | ||

Sicras-Mainar A, Rejas J, Navarro R, et al. Treating patients with fibromyalgia in primary care settings under routine medical practice: a claim database cost and burden of illness study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(2):R54. | ||

Collado A, Gomez E, Coscolla R, et al. Work, family and social environment in patients with Fibromyalgia in Spain: an epidemiological study: EPIFFAC study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:513–515. | ||

McCluskey S, Brooks J, King N, Burton K. The influence of “significant others” on persistent back pain and work participation: a qualitative exploration of illness perceptions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:236. | ||

Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Wellington C, De Williams A. Pain communication in the context of osteoarthritis: patient and partner self-efficacy for pain communication and holding back from discussion of pain and arthritis-related concerns. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(8):662–668. | ||

Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Morley-Forster PK. Chronic pain in Canada – prevalence, treatment, impact and the role of opioid analgesia. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7(4):179–184. | ||

Hill CL, Parsons J, Taylor A, Leach G. Health related quality of life in a population sample with arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(9):2029–2035. | ||

Tuzun EH, Albayrak G, Eker L, Sozay S, Daskapan A. A comparison study of quality of life in women with fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(4):198–202. | ||

Henwood P, Ellis JA. Chronic neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury: the patient’s perspective. Pain Res Manag. 2004;9(1):39–45. | ||

da Cruz DA, Pimenta CA, Kurita GP, de Oliveira AC. Caregivers of patients with chronic pain: responses to care. Int J Nurs Terminol Classif. 2004;15(1):5–14. | ||

Bigatti SM, Cronan TA. An examination of the physical health, health care use, and psychological well-being of spouses of people with fibromyalgia syndrome. Health Psychol. 2002;21(2):157–166. | ||

Miller LR, Cano A. Comorbid chronic pain and depression: who is at risk? J Pain. 2009;10(6):619–627. | ||

Ferrell B. Pain observed: the experience of pain from the family caregiver’s perspective. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17(3):595–609. | ||

Ferrell BR, Grant M, Borneman T, Juarez G, Ter Veer A. Family caregiving in cancer pain management. J Palliat Med. 1999;2(2):185–195. | ||

Redinbaugh EM, Baum A, DeMoss C, Fello M, Arnold R. Factors associated with the accuracy of family caregiver estimates of patient pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(1):31–38. | ||

Yeager KA, Miaskowski C, Dibble SL, Wallhagen M. Differences in pain knowledge and perception of the pain experience between outpatients with cancer and their family caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(8):1235–1241. | ||

Woolf AD, Zeidler H, Haglund U, et al. Musculoskeletal pain in Europe: its impact and a comparison of population and medical perceptions of treatment in eight European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(4):342–347. | ||

Mogil JS. Social modulation of and by pain in humans and rodents. Pain. 2015;156(Suppl):S35–S41. | ||

Price DD. Central neural mechanisms that interrelate sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Mol Interv. 2002;2(6):392–402. | ||

Azevedo LF, Costa-Pereira A, Mendonça L, Dias CC, Castro-Lopes JM. Chronic pain and health services utilization: is there overuse of diagnostic tests and inequalities in nonpharmacologic treatment methods utilization? Med Care. 2013;51(10):859–869. | ||

Pérez C, Navarro A, Saldaña MT, Wilson K, Rejas J. Modeling the predictive value of pain intensity on costs and resources utilization in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(3):273–279. | ||

Levinson D, Karger CJ, Haklai Z. Chronic physical conditions and use of health services among persons with mental disorders: results from the Israel National Health Survey. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(3):226–232. | ||

Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain and frequent use of health care. Pain. 2004;111(1–2):51–58. | ||

Keeley P, Creed F, Tomenson B, Todd C, Borglin G, Dickens C. Psychosocial predictors of health-related quality of life and health service utilisation in people with chronic low back pain. Pain. 2008;135(1–2):142–150. | ||

Failde I, Dueñas M, Salazar A, Ojeda B, Torres LM, Mico JA. Impacto del dolor crónico en la población general española: Resultados del observatorio del dolor. Rev la Soc Española del Dolor Resúmenes Ponencias. 2013;20(I):31–32. Spanish. | ||

Toliver-Sokol M, Murray CB, Wilson AC, Lewandowski A, Palermo TM. Patterns and predictors of health service utilization in adolescents with pain: comparison between a community and a clinical pain sample. J Pain. 2011;12(7):747–755. | ||

Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G, Leden I, Scherstén B. Impact of chronic pain on health care seeking, self care, and medication. Results from a population-based Swedish study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(8):503–509. | ||

Von Korff M, Lin EH, Fenton JJ, Saunders K. Frequency and priority of pain patients’ health care use. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(5):400–408. | ||

Collantes-Estevez E, Fernandez-Perez C. Improved control of osteoarthritis pain and self-reported health status in non-responders to celecoxib switched to rofecoxib: results of PAVIA, an open-label post-marketing survey in Spain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19(5):402–410. | ||

Agüera L, Failde I, Cervilla JA, Diaz-Fernandez P, Mico JA. Medically unexplained pain complaints are associated with underlying unrecognized mood disorders in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:17. | ||

Nakamura M, Nishiwaki Y, Ushida T, Toyama Y. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic musculoskeletal pain in Japan. J Orthop Sci. 2011;16(4):424–432. | ||

Donmez A, Karagulle MZ, Tercan N, et al. SPA therapy in fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled clinic study. Rheumatol Int. 2005;26(2):168–172. | ||

Gerstle DS, All AC, Wallace DC. Quality of life and chronic nonmalignant pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2001;2(3):98–109. | ||

Liedberg GM, Henriksson CM. Factors of importance for work disability in women with fibromyalgia: an interview study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47(3):266–274. | ||

Salido M, Navarro P, Judez E, Hortal R. Factores relacionados con la incapacidad temporal en pacientes con fibromialgia. Reumatol Clin. 2007;3(2):67–72. | ||

Neumann L, Buskila D. Quality of life and physical functioning of relatives of fibromyalgia patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1997;26(6):834–839. | ||

Söderberg S, Strand M, Haapala M, Lundman B. Living with a woman with fibromyalgia from the perspective of the husband. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42(2):143–150. | ||

Hinds C. The needs of families who care for patients with cancer at home: are we meeting them? J Adv Nurs. 1985;10(6):575–581. | ||

Miaskowski C, Kragness L, Dibble S, Wallhagen M. Differences in mood states, health status, and caregiver strain between family caregivers of oncology outpatients with and without cancer-related pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(3):138–147. | ||

Dellaroza MS, Pimenta CA, Lebrao ML, Duarte YA. Association of chronic pain with the use of health care services by older adults in Sao Paulo. Rev Saude Publica. 2013;47(5):914–922. Portuguese. | ||

Garcia-Martinez F, Herrera-Silva J, Guilar-Luque J. Management of chronic pain in primary health care. Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2000;7(7):453–459. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.