Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

A Multilevel Study of Change-Oriented Leadership and Commitment: The Moderating Effect of Group Emotional Contagion

Authors Lee MH , Wang C, Yu MC

Received 13 August 2022

Accepted for publication 17 February 2023

Published 7 March 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 637—650

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S385385

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Meng-Hsiu Lee,1 Chan Wang,2 Ming-Chu Yu3

1Department of Management Sciences, Tamkang University, New Taipei City, Taiwan; 2School of Humanities, Jinan University, Zhuhai City, People’s Republic of China; 3Department of Public Administration and Management, National University of Tainan, Tainan City, Taiwan

Correspondence: Chan Wang, School of Humanities, Jinan University, 206 Qianshan Road, Zhuhai City, Guang Dong Province, 519070, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 0756 8505920, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to explore the effects of change-oriented leadership on employee change commitment, and the underlying cross-level mediating and moderating effects.

Design and Methodology: Multilevel analysis of data from 583 respondents in 55 major manufacturing firms in China from 2021, reveals that change-oriented leadership explains the significant variance in change commitment. Based on Emotions as Social Information Theory and Social Exchange Theory, this study investigates the relationship between change-oriented leadership and change commitment fully mediated by emotion regulation.

Findings: This study also confirms that positive group emotional contagion has moderating effects on the relationship between change-oriented leadership and emotion regulation. In addition, negative group emotional contagion has moderating effects on the relationship between emotion regulation and change commitment. Furthermore, the moderated mediation of negative group emotional contagion is identified.

Originality and Value: This study makes a unique contribution through its multilevel approach to examining the relationship between leadership, emotion, and commitment during organizational change.

Keywords: change-oriented leadership, change commitment, group emotional contagion, emotion regulation, multilevel moderated mediation

Introduction

Modern organizations face a more complex, fast-paced, and turbulent environment than ever before, such as facing the challenges of the new era of artificial intelligence and sustainability in post-epidemic era, with an alarmingly high failure rate for organizational change and innovation initiatives.1–4 Several studies suggest that leaders and employees attribute different influences toward successful change.5,6 Leadership has been identified as the main reason for the success or failure of team-based organizational systems, which are the basic functional units of an institution.7–10 Thus, leaders must overcome and adapt to challenges and major changes by cultivating relationships with their employees, as the ability of leaders to convince employees to support change is vital to organizational success.11–13 Specifically, change-oriented leadership (COL) is a leader who can articulate vision, encourage innovative thinking, express optimism, develop motivation and commitment to organizational change and new strategies, and instill confidence that strategic vision is achievable.14–16 COL requires the ability to assess the external environment, envision beneficial changes, encourage innovation, and take risks to promote change.15,17 In times of turbulence, COL is important in shaping employees’ perceptions and responses to change.18,19 Thus, employees play a critical role in successful organizational change, as they are required to become more proactive and flexible when dealing with task-related or rearrangement issues,20 and this is where it is critical that employees demonstrate change commitment, that is defined by his or her mindset and willingness to support, adjust to, and ensure the success of the proposed changes.21,22

Based on social exchange theory, after employees receive support and engage in positive interactions with their leaders, they feel obliged to reciprocate.23 This framework has been applied to clarify empirical associations among COL and change commitment. However, theoretical understanding of these relationships is limited. Although researchers have accumulated knowledge on how leadership affects employees’ change commitment,11,24 the mechanisms behind employees’ emotional transformations and reactions to change, such as process-based approaches, have not been examined in detail,25,26 Therefore, a more thorough investigation can adopt a systematically quantitative method to measure employees’ behavioral and emotional dimensions in organizational change.27

Based on the above, this study proposes that the mediator, individuals’ emotion regulation, is responsible for transmitting the effects of COL to change commitment. Emotion regulation is a series of individual emotional strategies, oriented to stimulate, maintain, change, and manage own emotions, which can have a substantial impact on the individual’s way of thinking and behavior.28 Therefore, employees using emotion regulation strategies to improve their feelings will increase the experience of positive emotions at work.29 The emotional approach of change commitment suggests that scholars must consider employees’ emotional statuses in order to fully understand the relationship between context and individual commitment.30 As thus, there is a great need for research on the relationship between leadership, emotion, and individuals’ emotion regulation at work.31 Little is understood about COL and how it influences employees’ emotion regulation and change commitment. Given that commitment is a result of emotional processes in organizational change,30 this study argues that individual emotion regulation is a crucial individual-level factor mediating the relationship between COL and change commitment.

Theoretical understanding is further lacking as there is limited insight into the contextual factors that influence change leadership-commitment associations. Based on the job demands-resources model, leaders’ support for organizational change may trigger a motivational process enhancing job engagement, job-related learning, and organizational commitment.32,33 In particular, employees faced with workplace turbulence and uncertainty also feel pressure from leaders during organizational change. As a result, the patterns of group-shared emotions formed by employees play an important role in determining employees’ attitudes and change commitment.34,35 Depending on the collective emotions, group members may experience and demonstrate different feelings and behaviors in perception of leadership.36 In positive group emotional contagion (PGEC), employees will improve task performance by enhancing cooperation and self-perception, and reducing conflict. Therefore, PGEC may positively moderate the relationship between leadership and emotion regulation.

In addition, based on emotions as social information theory, employees are influenced by the understandings and attitudes of others in their organizational context.37,38 As a result, negative group emotional contagion (NGEC) leads team members to feel unhelpful, frustrated, and depressed, and more likely to suppress their real emotions.39 Furthermore, according to the model of emotion regulation of others and self (EROS),40 individuals are motivated to improve or worsen their emotions. Therefore, the employees’ affect-improving emotion regulation involve cognitive reappraisal of affective experiences, and deploying attention by distraction when encountering difficult events, such as NGEC.29 Thus, this research further examines the moderators of NGEC in the relationship between emotion regulation and commitment.

This study contributes to leadership and commitment literature in several ways. Finding the right design for such research is crucial.41 According to the meso-mediational relationship perspective, research in organizational behavior should focus on a multilevel viewpoint to comprehensively understand management.42 The lack of studies with an appropriate research design seriously limits understanding of how COL impacts commitment.43 It is important to investigate different levels of employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward change,25 which may be achieved by using a multilevel perspective. Given that the change commitment of employees provides the basis for successful organizational change, understanding how COL influences employees’ commitment is essential.

Based on emotions as social information theory, this study investigates the cross-level mediating effects of individual emotion regulation on the relationship between leadership and commitment, and further confirms the moderating effect of group emotion contagion. Expanding research to an international arena to seek cross-national generalizability is important, especially in the current global business environment. Specifically, market opportunities in China are expanding rapidly and are very attractive to multinational companies. This highly competitive atmosphere leads to frequent organizational change. Thus, this research can contribute to the organizational change literature by examining leadership, emotion, and commitment issues in the Chinese context. A research framework adopting a multilevel perspective among variables is presented as Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical framework. |

Theory and Hypotheses

Change-Oriented Leadership and Commitment

A leader’s change-oriented vision might have a positive indirect relationship with employees’ change commitment.11,24 In other words, the ability of the leader to deliver this vision is also predicted to have a positive indirect relationship with change commitment. COL also encourage innovative ways to solve problems, facilitate the process of helping followers absorb new knowledge, and think “outside of the box.”14,16 In addition to promoting change by conceiving and encouraging innovation, COL will also convey the need for change, to preempt resistance and pitfalls in the process of change.15 As the organizational change process unfolds, leaders face many challenges in their attempts to facilitate learning among subordinates;44 however, they still must empower, motivate, and inspire their employees.45 Specifically, employees look to their leaders as a source of certainty and as thus, may be more attentive to their guidance and actions amid organizational change.11,13 Thus, successful formation and assimilation of the company vision increases employees’ change commitment due to increased identification and emotional bonding with the organization, which are critical for fostering a willingness to contribute.46 In other words, a clearer articulation of the company’s vision may lead to increased change commitment.32,46 Therefore, this study proposes that employees’ change commitment is increased by leaders who create a “glorious vision” and are good at communicating this vision with their subordinates.

Hypothesis 1: COL positively influences change commitment.

Multilevel Mediating Effect of Individual Emotion Regulation

Specific information about the emotions that leaders and employees experience during interactions, and how these emotions are managed would increase understanding of how both parties appraise the leadership process.26,30 An employee’s emotion regulation is strongly related to the relationship with their leaders.30 It is possible that change-oriented leaders might interact with their employees differently, such as communicating more frequently. In other words, when employees perceive COL, they will select and modify affect-eliciting situation, redeploy their attention from or reevaluate affective-laden events, and modulate their own emotions.26,47 Thus, this study proposes that COL influences individual emotion regulation through leaders’ frequent communication and clear delivery of a powerful vision.

Different types of commitment may be related to different regulatory foci.48 According to Regulatory Focus Theory, a promotion focus is related to affective commitment.49 During times of organizational change, employees will support change and demonstrate trust, confidence, and commitment because they are psychologically prepared and willing to cooperate with their leaders.50 This infers employees who more willingly express positive attitudes towards one another, despite inner feelings of boredom or irritation, have stronger change commitment to their company.

Leaders’ personal attributes influence the choices and the decisions they make; these decisions in turn influence employees’ attitudes and beliefs.51 Similarly, employees’ key work-based experiences (which can be grouped into three major categories: organizational rewards, procedural justice, and supervisor support) are positively related to their affective commitment.32,52 Thus, according to Social Exchange Theory, employees and leaders develop non-specific obligations and responsibilities through the process of social exchange and interaction. If employees feel supported and have positive interactions with their leaders, they will feel obliged to reciprocate.23 When there are positive interactions between employees and leaders, employees accept the content and delivery of the leaders’ vision and closely regulate their emotions. Therefore, individual emotion regulation is a prominent yet complex facet of leader-follower relationships, with both negative and positive potential effects for leaders and employees. Based on this reasoning, the second hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 2: COL positively influences change commitment through the mediating effect of individual emotion regulation.

Moderation and Moderated Mediation of PGEC

Collective emotions can influence the ways in which various groups think and behave in relation to both the organization and other groups within it.43,53 Communication is important for improving employees’ commitment, which increases the likelihood of positive outcomes.54 According to the job demands–resources model, leadership and leader support (external resources) may cause motivation processes for employees to enhance their job performance and change commitment in organizational change.33 Therefore, PGEC (a group-based increase in positive mood) may help employees believe they can achieve the expected job performance within the organization.55 In addition, PGEC will promote employees’ career development, and employees will be more successful in work performance and have better mental health.56 Therefore, the more positive the group emotional contagion, the more resources employees can reallocate. This will reduce the pressure employees feel during organizational change.

An employee displaying positive emotions is likely to elicit favorable responses from his or her supervisors, co-workers, and customers, which in turn increases the employee’s personal job satisfaction. As PGEC lowers the likelihood of inter-group conflict,43 organizations with high PGEC will have employees with greater organizational trust, positive emotions, and fewer conflicts at work. At this time, employees’ emotional regulation is an individual factor involved in constructing a positive emotional experience, which helps to propose ideas for improvement and change at work.29 This, in turn, can increase employees’ change commitment.34

Change commitment develops through social exchange mechanisms resulting from positive work experiences, which increases individuals’ commitment levels.52 Change-oriented leaders shape company visions and moods, and transmit them to employees. These then become contagious amongst employees (PGEC), leading them to more positive interactions and change commitment, and less conflict.34,46,57 Furthermore, based on EROS,40 the employee-controlled intrinsic emotion regulation is related to their experience of positive emotional state at work. Emotion regulation plays a central role in human adaptation through the process of satisfying and approaching pleasure.58 In the case of employee perception COL and PGEC, employees will recognize the positive aspects of the situation, consider their own positive characteristics, and connect with positive emotions. When employees focus on comfortable or happy activities, it can ultimately lead to positive work results. Thus, this research proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: PGEC moderates the positive relationship between COL and emotion regulation, such that the positive relationship is stronger when PGEC is high. Hypothesis 3b: PGEC moderates the positive indirect effect of COL on change commitment through emotion regulation, such that this indirect effect is stronger when PGEC is high.

Moderation and Moderated Mediation of NGEC

Based on Emotions as Social Information Theory, employees are easily influenced by others’ emotions and attitudes in their working environment, especially negative emotions among team members.38 NGEC makes team members feel more helpless, frustrated and depressed, and more likely to suppress their real emotions.39 Therefore, when employees perceive NGEC, the negative impact on their emotion regulation and mental health is significant. At this time, employees will have affect-worsening emotion regulation, such as thinking about negative experiences or their own shortcomings, and the positive affect of employees should be reduced.29 In other words, when team members have negative emotions, the perceptions of COL tend to be negative, which reduces the individual’s emotion regulation and work attitudes. This eventually leads to employees’ distrust, resistance, inability to work and reduction of commitment to change. Therefore, the following is proposed:

Hypothesis 4a: NGEC moderates the positive relationship between emotion regulation and change commitment, such that the positive relationship is weaker when NGEC is high. Hypothesis 4b: NGEC moderates the positive indirect effect of COL on change commitment through emotion regulation, such that this indirect effect is weaker when NGEC is high.

Materials and Methods

Sample and Data Collection

The sampling targets the multinational companies in China, and we focus on companies from China because in recent years global firms have eagerly invested in China. Market opportunities are expanding rapidly and are very attractive, especially in terms of Chinese domestic demand. The key characteristics of the Chinese market are that it is dynamic, uncertain, and highly competitive; as a result, organizational change happens frequently and aggressively. By studying this sample, we can thus collect and investigate data from many companies that undergo organizational change. Two-stage sampling was performed in this study. The first step is to confirm that the company has indeed undergone organizational changes in 2020–2021. In total, 55 companies were identified as implementing changes, including layoffs and organization downsizing (39%), leader replacement (31%), workflow change (24%), and strategy change (6%). In the second stage, we sent 1400 questionnaires to the company using a stratified sampling method. A total of 604 questionnaires were collected. We removed substandard questionnaires by excluding missing data and used single imputation to confirm questionnaire completeness. Finally, 583 valid questionnaires were collected, and the response rate was 41.64%. These 583 employees came from 55 companies.

We collected demographic information on the respondent’s gender, age, marital status, education, position, and tenure at the company as well as the firm size and type of change experienced. A relatively equal distribution of male (n=325) and female (n=258) respondents was obtained. The average age of respondents was 37.9 years old; most were married (n=348, versus n=235 for single employees), and most were university-educated (n=334, versus n=2 for junior high school, n=92 for senior high school, and n=155 for graduate school). The average tenure of respondents was 13.8 years. The average firm had 163.26 employees, and we collected two types of organizational change, 331 respondents came from companies undergoing mission and strategy changes, while 252 came from companies conducting undergoing structural changes.

In advance, this study adopts multiple data collection methods in order to reduce the risk of common method variance. The supervisors and subordinates must complete different sections of questionnaires at different sampling time periods to collect multilevel-data. First, supervisors will be asked to finish items about COL. After a month, the subordinates were asked to complete the questionnaires of change commitment, emotion regulation and group emotion contagion.

Respondent Evaluation

To assess respondents’ familiarity with the research topic, we included three questions on a five-point scale at the end of the questionnaire. The average composite rating is 4.03, indicating that the respondents understand this topic. In addition, the demographic survey of the respondents found that the average tenure was 13.8 years, indicating that the respondents have a certain degree of familiarity with the work content they are responsible for, especially when facing organizational changes. These results demonstrate that respondents are experienced and knowledgeable about the research topic, providing confidence in data quality and sample representativeness.

Measures: Group Level

COL. The questionnaire was adopted by Sirén et al.59 On the questionnaire, each vision statement was evaluated on a five-point scale assessing whether or not the theme was present in the statement. The scale based on 6 items, and sample items include the following: “Could you describe the mission/vision specifically.” The response options range from 1 to 5 (1= strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). Alpha reliabilities were 0.862 for vision content and 0.799 for vision delivery.

Group emotional contagion. The emotional contagion scale developed by Doherty60 includes the five basic emotions of love, happiness, anger, fear, and sadness and assesses an individual’s susceptibility to “catch” an emotion expressed by another person. It was ultimately developed into a 6-item version to test PGEC (two sub-dimensions, love and happiness). The response options range from 1 to 5 (1= strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha for PGEC was 0.931. Sample items include the following: “When someone smiles warmly at me, I smile back and feel warm inside.” We also used the emotional contagion scale (Doherty, 1997) to measure NGEC. The measure includes 9 items that tap three dimensions: anger, fear and sadness. Sample item is “I feel tense when overhearing an angry quarrel.” The Cronbach’s alpha for NGEC was 0.916.

Measures: Individual Level

Individual Emotion Regulation

We adopted the emotion regulation questionnaire developed by Gross and John61 which comprises 10 items (six for the reappraisal factor and four for the suppression factor). Sample items include the following: “I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in” and “I control my emotions by not expressing them.” The response options range from 1 to 5 (1= strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). Alpha reliabilities were 0.815 for reappraisal and 0.829 for suppression.

Change Commitment

We measured the change commitment that is consistent with Fedor et al.62 This scale included four items and sample item is “I think this employee can do whatever he/she can to help this organizational change be successful.” Responses were collected with a Likert scale in which “1” was “strongly disagree” and “5” was “strongly agree”, and higher scores indicate an employee’s higher degree of change commitment.

Control Variables

Individual-level control variables included gender, age, marital status, education, tenure, and job position. Group-level control variable was firm size and type of organizational change. The type of organizational change divided into three types: strategic transformational change, structural change, and people-centric organizational change. Performing statistical analysis in the form of dummy variables. These control variables are commonly used in studies of work attitudes.

Results

Firstly, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS to assess the discriminant validity. Second, SPSS was used to test the appropriateness of aggregation for the group-level variables, COL and group emotional contagion. Next, we also used SPSS to test the correlation and descriptive statistics of each variable. Furthermore, hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was used to assess the relationships between variables to conduct hypothesis testing. Finally, we adopt Mplus to test a moderated mediation model.

Preliminary Analyses

Prior to testing the hypothesized model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the discriminant validity of the four constructs: COL, group emotional contagion, individual emotion regulation, and change commitment. The results show that the five-factor model provided a good fit for the data and a better fit than the alternative models (see Table 1). The model was thus fit with four factors loading separately (x2/df= 1.715, p<0.001, RMSEA= 0.035, GFI= 0.901).

|

Table 1 Comparison of Potential Models |

Data Aggregation

We first tested the appropriateness of aggregation for the COL and group emotional contagion variables.11 In this study, group-mean centering was used, which the explanatory variable(s) are centered around the group mean. To test the within-group agreement and between-group agreement, we used the within-group indexes (rwg) to examine the variables.63 The mean rwg values for COL, PGEC and NGEC were 0.95, 0.95 and 0.97, respectively. Both variables were thus highly consistent within groups. We also considered intra-class correlations (ICC1 and ICC2;64): ICC1 represents the variation within a group, while ICC2 shows the reliability at the group level.64 The ICC1 and ICC2 values for COL were 0.302 and 0.826, respectively. The corresponding values for PGEC were 0.612 and 0.946, and for NGEC were 0.618 and 0.945. These indexes thus generally supported the appropriateness of aggregation.63

The group-level variables for COL, PGEC and NGEC were confirmed to be distinctive by examining the results of the measurement model via CFA. Thus, the subjective assessments of interdependence and group mechanisms accurately measured the extent of dependence of a group member on other members and interactions within the group, and the inter-rater agreement indices (ICCs and rwg) supported aggregation.

Correlation

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2, showing generally significant correlations between variables. At the individual level (level 1), emotion regulation and change commitment were significant related (γ=0.403, p<0.01). At the group level (level 2), there were significant relationships between COL and PGEC (γ=0.328, p<0.01); COL and NGEC (γ=−.112, p<0.05); and PGEC and NGEC (γ=−.455, p<0.01).

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations |

Mediation Through Emotion Regulation

Due to the multilevel nature of the data, hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was used to assess the relationships between the group level and the individual level. HLM ensures the appropriateness of analysis when multiple levels of data are involved by maintaining the appropriate independence requirement for the predictor variables. The null model let us test the between-group variance by examining the level 2 residual variance of the intercept (τ00) and the ICC1 statistic.65 The results indicated that variation within change commitment was highly significant (τ00 =0.186, p<0.001), σ2=0.437. ICC1 indicated that 30% of the variation came from within the group; in other words, 70% of the variation was between groups. The null model test supported the appropriateness of cross-level analysis.

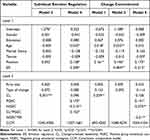

Table 3 presents the results from the HLM analysis. The results of Model 1 showed that COL positively influenced change commitment (γ=0.329, p<0.01). Hence, Hypothesis 1 was supported. The Model 2 revealed that COL had a positive influence on individual emotion regulation (γ= 0.501, p< 0.01); The Model 3 results indicated that individual emotion regulation positively influenced change commitment (γ=0.484, p<0.01). To test Hypotheses 2, we follow Baron and Kenny66 recommended three conditions for confirming a mediating effect. The significant effects of COL on change commitment were insignificant when we added the emotion regulation to the model (see Model 4). Based on Shen et al.67 PRODCLIN can be used to obtain more accurate confidence limits for the indirect effect. We confirmed that the 93% confidence interval of the indirect effect was significant after using PRODCLIN. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

|

Table 3 HLM Results |

Moderation of PGEC and NGEC

We further checked Model 4 in Table 3, the change leadership*PGEC interaction was significantly related to emotion regulation (γ=0.152, p<0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 3a was supported. The whole meso-moderated model explained 23% of the variance in the outcome variable (R2=0.23). Therefore, the positive effect of change leadership on emotion regulation was higher when the level of PGEC was high and vice versa. Figure 2 illustrates this significant moderating effect. As shown in Figure 2, the effect of change leadership on emotion regulation was stronger when the level of PGEC was high.

|

Figure 2 Interaction plot for emotion regulation. |

We then tested Hypothesis 4a, Model 5 showed that the change NGEC* emotion regulation interaction was significantly related to change commitment (γ=−.21*p<0.01). The whole meso-moderated model explained 49% of the variance in the outcome variable (R2=0.49). Therefore, the positive effect of emotion regulation on change commitment was lower when the level of NGEC was high and vice versa, supporting Hypothesis 4a. Figure 3 illustrates this significant moderating effect. As shown in Figure 3, the effect of change leadership on emotion regulation was weaker when the level of NGEC was high.

|

Figure 3 Interaction plot for change commitment. |

Moderated Mediation of PGEC and NGEC

Moderated mediation shows that the indirect effect varies with the different levels of the moderator.68 Based on the suggestions of scholars,68 we use Mplus to calculate the bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects of change leadership on change commitment via individual emotion regulation at “high” and “low” values of positive and negative group emotional contagion (one standard deviation above and below the average). Table 4 shows comparisons of conditional indirect effect of COL in different values of moderators. For PGEC, the indirect effects of change leadership via emotion regulation on change commitment do not differ significantly when PGEC is at high versus low levels (indirect effect=0.01; p>0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 3b is not supported. For NGEC, the indirect effects of change leadership via emotion regulation on change commitment differ significantly when NGEC is at high versus low levels (indirect effect=0.17, p<0.05, 95% CI: 0.08–0.25). As such, Hypothesis 4b is fully supported.

|

Table 4 Moderated Mediation Model |

Discussion and Conclusion

This study explores the effects of group-level COL on individual-level change commitment, through the mediation of individual emotion regulation and moderation of group emotional contagion via a multilevel analysis. The results confirm that COL plays a substantial role in the enhancement of employees’ change commitment, which is consistent with the findings of.11,24,32 A COL, such as depicting a vision for the future with lucid details, can help guide employees as organizations undergo change. When employees perceive COL, they have a sense of belonging and identification that increases their willingness to be involved in the organization’s activities, pursue the organization’s goals, and remain with the organization.32,52 Communication is important to improve employees’ levels of commitment,54 and the methods used to communicate (deliver the vision) to employees can enhance their change commitment. This study’s results also show significant positive relationships between COL and change commitment.

The results also demonstrate the mediating effect of individual emotion regulation. According to Social Exchange Theory, the content and delivery of leaders’ visions can improve interactions between leaders and employees, and enhance employees’ feelings of responsibility and ambition. Meanwhile, employees will reappraise and reduce the perceived drawbacks of organizational change.30 Finally, when employees have higher levels of change commitment, leaders’ communication is reciprocated by employees.23

Additionally, the research findings support the argument that COL has a significant positive influence on change commitment, through the mediating effect of individual emotion regulation. When employees internalize a leader’s values, their motivational orientations shift from being self-interested to focusing on the visions and ambitions of their leader and organization. In other words, a leader engaging in COL influences the emotion regulation of his or her employees, which then increases their change commitment to the organization. Employees with strong emotion regulation have fewer conflicts with others, a greater ability to adjust to group settings, and are more likely to have higher levels of change commitment.

The results further indicate that NGEC moderates the relationship between emotion regulation and change commitment. When employees realize that they must adapt to the working environment, they tend to take the same attitude and action as their team members, which leads to team emotional contagion. Based on Emotions as Social Information Theory, team and contextual information will transmit norms, expectations and restrictions.38 As a result, employees are vulnerable to the emotions and attitudes of coworkers, especially negative emotions among team members.38 NGEC makes team members feel more helpless, frustrated, depressed, and more likely to suppress their true emotions.39 Therefore, during the turbulence and uncertainty of organizational change, when employees are immersed in NGEC, the negative effects on their emotion regulation and mental health are significant, and finally may weaken the change commitment.

This empirical research confirms that NGEC moderates the positive indirect effect of COL on change commitment through emotion regulation. In other words, when team members have negative emotions, they tend to have negative perspectives on COL, which reduces emotion regulation and work attitude. This will eventually lead to mistrust, resistance, inability to work and a reduction in change commitment.

The moderating effect of PGEC is significant. However, the moderated-mediating effect of PGEC is not significant. Theoretically, PGEC plays an important role in building team cooperation and team cohesion. However, when team members are faced with organizational change, the uncertainty and turbulence of the future still results in the accumulation of team members’ negative emotions. Particularly in Chinese society where a culture of collectivism has resulted in more significant NGEC in organizational change.69 As a result, the influence of PGEC may be diluted and as thus, cannot illustrate a moderating effect.

Finally, Emotions as Social Information Theory and Social Exchange Theory suggest that organizational and contextual factors must be considered.37,38 HLM was adopted as an analytical approach to measure employees’ behavioral and emotional dimensions toward leadership during change.27

Practical Implications

During the process of organizational change, the first step is allocating a change-oriented leader. The traits of COL are having a lucid vision and inspirational communication. Leaders should be clear about the where the company is heading and direct in leading colleagues and employees. In addition, leaders should understand how to motivate employees and instill pride in them for being part of the organization. To do this, leaders speak positively and encourage employees to realize that a changing environment means more opportunities. In practice, the priority of organizational change is to select a competent leader who possesses the characteristics of COL.

Employees’ emotion regulation will be positively influenced by COL, which ultimately enhances change commitment. In other words, employees’ reappraisal ability and suppression ability will support them through the turbulence of organizational change. In terms of reappraisal ability, employees will change the way they think about the situation to control their emotions. In particular, when employees want to feel fewer negative emotions (such as sadness or anger) or feel more positive emotions (such as joy or amusement), they can achieve their goals by changing what they think about. In terms of suppression ability, when faced with the pressure of organizational change, employees will control their emotions by not expressing them. Therefore, in practice, leaders must understand the emotion regulation of employees and coach them appropriately.

This research’s ultimate goal is to discover how to best enhance employees’ change commitment during organizational change, so employees are willing to contribute as much as possible toward the success of organizational change. The process of organizational change needs the full support of employees, as well as assistance from employees to persuade others to support the change. If employees fully support their supervisors, the process of change will be smoother. Therefore, in practice, managers should think about how to enhance the change commitment of employees to implement the change successfully.

Finally, group emotional contagion is the critical moderator during organizational change and particularly, NGEC can cause significant harm to successful change. Supervisors and leaders should pay special attention to three factors of NGEC: fear, anger and sadness. In terms of fear, some employees are easily affected by other team members’ tense emotions and stress, which makes them feel nervous. In terms of anger, supervisors must consider how to reduce the occurrence of team members’ disputes or disagreements. Lastly, in terms of sadness, employees are particularly vulnerable to the influence of others’ crying and often also get teary-eyed. These depressing and sad circumstances can easily lead to NGEC. Supervisors should consider how to alleviate these negative situations.

In conclusion, inspirational visions are thought to elevate employees’ levels of commitment and willingness to make sacrifices for the organization. Therefore, leaders should use change-oriented styles to target emotions through group emotional contagion and individual emotion regulation. Leaders must be cautioned, however, that negative, as well as positive, emotions can be contagious among employees. To prevent this, leaders should develop a “glorious vision” of the future and share it using exceptional verbal and nonverbal communication skills. A change-oriented leader will have a lucid vision and use persuasive communication to transfer a positive, change-embracing attitude to others. This is especially relevant for organizations undergoing continuous change.

While an organization’s work atmosphere is invisible, it still plays an important role in employees’ feelings toward work and their commitment to the firm. This study suggests that leaders should foster a positive and harmonious work atmosphere for employees, while simultaneously attempting to reduce the negative working atmosphere. Doing so may increase employees’ willingness to put more effort into their work and raise their levels of change commitment.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The limitations of this study point toward possible directions for future research. First, this study provides evidence that emotion-related variables (group emotional contagion and individual emotion regulation) play an important role in the success of COL. However, it is difficult to infer how relationships have developed and to assess employees’ perceptions when leaders use COL. To address this, longitudinal studies of the process by which COL influences employees’ emotions and perceptions should be conducted. Future research could seek to identify the different stages of the change process and the variables associated with each individual stage.

There are also limitations related to measurement. In particular, the unique characteristics of the sample may limit the generalizability of the findings. As organizational change is dynamic in nature, future research should examine the use of rhetoric to communicate a vision in COL and compare this across settings.

In addition, regarding the measurement of emotion regulation variables, this study proposed that emotion regulation is a uni-dimensional variable can be used to measure the relationship between it and other variables in theoretical framework. It is suggested that future research can divide emotional regulation into two sub-dimensions (expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal) to clarify the different influences of these two sub-dimensions on other variables.

Furthermore, this research proposed the multilevel model for five critical variables. Another consideration of recommendations for future research is scholars can investigate the influence of other different variables (eg, contextual variable, antecedent and consequent) on this research model.

Finally, this research adopts quantitative research methods to test the multilevel model by using HLM. Future research can adopt other methodology (eg, qualitative methods, experiment survey, grounded theory, and discourse analysis) to further clarify the relationship among these variables.

Ethical Consideration

The questionnaires strictly followed the principle of informed consent, and the study was approved by Taiwan National Cheng Kung University Human Research Ethics Committee (NCKU HREC). This committee has been verified by the Ministry of Education of Taiwan. The investigators introduced the purpose and the basic information. During the whole study process, the privacy and anonymity of participants were fully protected. Informed consent was inferred by return of a completed questionnaire. The respondents were informed about the objective, purpose, risks, and benefits of the study and the right to refuse to participate. The study posed a low or no more than minimal risk to the study participants. Also, the study did not involve any invasive procedures. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Al Halbusi H, Klobas JE, Ramayah T. Green core competence and firm performance in a post-conflict country, Iraq. Bus Strateg Environ. 2022;1–13. doi:10.1002/bse.3265

2. Fredberg T, Pregmark JE. Organizational transformation: handling the double-edged sword of urgency. Long Range Plann. 2022;55(2):1–19. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2021.102091

3. Herold DM, Fedor DB, Caldwell SD. Beyond change management: a multilevel investigation of contextual and personal influences on employees’ commitment to change. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(4):942–951. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.942

4. Khanna R, Guler I, Nerkar A. Fail of ten, fail big, and fail fast? Learning from small failures and R&D performance in the pharmaceutical industry. Acad Manage J. 2016;59(2):436–459. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.1109

5. Weber E, Büttgen M, Bartsch S. How to take employees on the digital transformation journey: an experimental study on complementary leadership behaviors in managing organizational change. J Bus Res. 2022;143:225–238. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.036

6. Pater R, Chapman J. Blueprints for successful cultural leadership. Occup Health Saf. 2015;84(9):114.

7. Fernandez S. Examining the effects of leadership behavior on employee perceptions of performance and job satisfaction. Public Perform Manag. 2008;32(2):175–205.

8. Nielsen BB, Nielsen S. Top management team nationality diversity and firm performance: a multilevel study. Strateg Manage J. 2013;34(3):373–382. doi:10.1002/smj.2021

9. Quansah E, Hartz DE. Strategic adaptation: leadership lessons for small business survival and success. Am J Bus. 2021;36(3/4):190–207. doi:10.1108/AJB-07-2020-0096

10. van Kleef GA, Homan AC, Beersma B, Van Knippenberg D, Van Knippenberg B, Damen F. Searing sentiment or cold calculation? The effects of leader emotional displays on team performance depend on follower epistemic motivation. Acad Manage J. 2009;52(3):562–580. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.41331253

11. Oreg S, Berson Y. Leadership and employees’ reactions to change: the role of leaders’ personal attributes and transformational leadership style. Persl Psychol. 2011;64(3):659–672.

12. Yam KC, Reynolds SJ, Zhang P, Su R. The unintended consequences of empowering leadership: increased deviance for some followers. J Bus Ethics. 2021;181:1–18.

13. Ye S, Yang Y, Wang W, Zhou X. Linking ethical leadership to employees’ change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: a multilevel moderated mediation model. Soc Behav Personal. 2022;50(7):1–14. doi:10.2224/sbp.11636

14. Mikkelsen A, Olsen E. The influence of change-oriented leadership on work performance and job satisfaction in hospitals - The mediating roles of learning demands and job involvement. Leadersh Health Serv. 2019;32(1):37–53. doi:10.1108/LHS-12-2016-0063

15. Øygarden O, Olse E, Mikkelsen A. Changing to improve? Organizational change and change-oriented leadership in hospitals. J Health Organ Manag. 2020;34(6):687–706. doi:10.1108/JHOM-09-2019-0280

16. Yukl G. Effective leadership behavior: what we know and what questions need more attention. Acad Manage Perspect. 2012;26(4):66–85. doi:10.5465/amp.2012.0088

17. Lam W, Lee C, Taylor MS, Zhao HH. Does proactive personality matter in leadership transitions? Effects of proactive personality on new leader identification and responses to new leaders and their change agendas. Acad Manage J. 2018;61(1):245–263. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0503

18. Demircioglu MA, Chowdhury F. Entrepreneurship in public organizations: the role of leadership behavior. Small Bus Econ. 2021;57(3):1107–1123. doi:10.1007/s11187-020-00328-w

19. Engelen A, Gupta V, Strenger L, Brettel M. Entrepreneurial orientation, firm performance, and the moderating role of transformational leadership behaviors. J Manage. 2015;41(4):1069–1097.

20. Burris ER, Rockmann KW, Kimmons YS. The value of voice to managers: employee identification and the content of voice. Acad Manage J. 2017;60(6):2099–2125. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0320

21. Ford JK, Lauricella TK, Van Fossen JA, Riley SJ. Creating energy for change: the role of changes in perceived leadership support on commitment to an organizational change initiative. J Appl Behav Sci. 2021;57(2):153–173. doi:10.1177/0021886320907423

22. Herscovitch L, Meyer JP. Commitment to change: extension of a three-component model. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(3):474–487. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.474

23. Eisenberger R, Fasolo P, Davis-LaMastro V. Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. J Appl Psychol. 1990;75(1):51–59. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.75.1.51

24. Ramos Maçães MA, Román-Portas M. The effects of organizational communication, leadership, and employee commitment in organizational change in the hospitality sector. Commun Soc. 2022;35(2):89–106. doi:10.15581/003.35.2.89-106

25. Shin J, Taylor MS, Seo MG. Resources for change: the relationships of organizational inducements and Psychological resilience to employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward organizational change. Acad Manage J. 2012;55(3):727–748. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0325

26. Slaughter JE, Gabriel AS, Ganster ML, Vaziri H, MacGowan RL. Getting worse or getting better? Understanding the antecedents and consequences of emotion profile transitions during COVID-19-induced organizational crisis. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(8):1118–1136. doi:10.1037/apl0000947

27. Luo Y, Jiang H. Effective public relations leadership in organizational change: a study of multinationals in Mainland China. J Public Relat Res. 2014;26(2):134–160. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2013.864241

28. Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: taking stock and moving forward. Emotion. 2013;13:359–365. doi:10.1037/a0032135

29. Madrid HP. Emotion regulation, positive affect, and promotive voice behavior at work. Front Psychol. 2020;11(1739):1–7. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01739

30. Glaso L, Einarsen SL. Emotion regulation in leader-follower relationship. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2008;17(4):482–500. doi:10.1080/13594320801994960

31. George JM. Emotions and leadership: the role of emotional intelligence. Hum Relat. 2000;53(8):1027–1055. doi:10.1177/0018726700538001

32. Cheol YK, Won-Woo P. Emotionally exhausted employees’ affective commitment: testing moderating effects using three-way interactions. Soc Behav Personal. 2015;43(10):1699–1714. doi:10.2224/sbp.2015.43.10.1699

33. Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(3):499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

34. Huy QN. Emotional balancing of organizational continuity and radical change: the contribution of middle managers. Admin Sci Quart. 2002;47(1):31–69. doi:10.2307/3094890

35. Sanchez-Burks J, Huy QN. Emotional aperture and strategic change: the accurate recognition of collective emotions. Organ Sci. 2009;20(1):22–34. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0347

36. Sy T, Côté S, Saavedra R. The contagious leader: impact of the leader’s mood on the mood of group members, group affective tone, and group processes. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(2):295–305. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.295

37. Shetzer L. A social information processing model of employee participation. Organ Sci. 1993;4(2):252–268. doi:10.1287/orsc.4.2.252

38. Van Kleef GA. Understanding the positive and negative effects of emotional expressions in organizations: EASI does it. Hum Relat. 2014;67(9):1145–1164. doi:10.1177/0018726713510329

39. Roberts S, O’Connor K, Aardema F, Bélanger C. The impact of emotions on body-Focused repetitive behaviors: evidence from a non-treatment-seeking sample. J Behav Ther Exp Psy. 2015;46:189–197. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.10.007

40. Niven K, Totterdell P, Holman D. A classification of controlled interpersonal affect regulation strategies. Emotion. 2009;9:498–509. doi:10.1037/a0015962

41. Hitt MA, Beamish PW, Jackson SE, Mathieu JE. Building theoretical and empirical bridges across levels: multilevel research in management. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(6):1385–1399. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.28166219

42. Mathieu JE, Taylor SR. A framework for testing meso-mediational relationships in organizational behavior. J Organ Behav. 2007;28(2):141–172. doi:10.1002/job.436

43. Barsade SG. The ripple effect: emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Admin Sci Quart. 2002;47(4):644–675. doi:10.2307/3094912

44. Chakravarthy BS. Adaptation: a promising metaphor for strategic management. Acad Manage Rev. 1982;7(1):35–44. doi:10.2307/257246

45. Hart S. An integrative framework for strategy-making processes. Acad Manage Rev. 1992;17(2):327–351. doi:10.2307/258775

46. Dvir T, Kass N, Shamir B. The emotional bond: vision and organizational commitment among high-tech employees. J Organ Change Manag. 2004;17(2):126–143. doi:10.1108/09534810410530575

47. Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998;2:271–279. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

48. Meyer JP, Becker TE, Vandenberghe C. Employee commitment and motivation: a conceptual analysis and integrative model. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89(6):911–1007. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.991

49. Kark R, Dijk DV. Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: the role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes. Acad Manage Rev. 2007;32(2):500–528. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.24351846

50. Rafferty AE, Simons RH. An examination of readiness for fine-tuning and corporate transformation changes. J Bus Psychol. 2006;20(3):325–350. doi:10.1007/s10869-005-9013-2

51. Berson Y, Oreg S, Dvir T. CEO values, organizational culture and firm outcomes. J Organ Behav. 2008;29(5):615–633. doi:10.1002/job.499

52. Allen NJ, Meyer JP. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: an examination of construct validity. J Vocat Behav. 1996;49(3):252–276. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1996.0043

53. Mackie DM, Devos T, Smith ER. Intergroup emotions: explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(4):602–616. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.602

54. Goris JR, Vaught BC, Pettit JD. Effects of communication direction on job performance and satisfaction: a moderated regression analysis. J Bus Commun. 2000;37(4):348–368. doi:10.1177/002194360003700402

55. Kelly JR, Barsade SG. Mood and emotions in small groups and work teams. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 2001;86(1):99–130. doi:10.1006/obhd.2001.2974

56. Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):803–855. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

57. Choi JN. Change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: effects of work environment characteristics and intervening psychological processes. J Organ Behav. 2007;28(4):467–484. doi:10.1002/job.433

58. Higgins ET. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am Psychol. 1997;52:1280–1300. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280

59. Sirén C, Patel PC, Wincent J. How do harmonious passion and obsessive passion moderate the influence of a CEO’s change-oriented leadership on company performance? Leadersh Quart. 2016;27:653–670. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.03.002

60. Doherty RW. The Emotional Contagion scale: a measure of individual differences. J Nonverbal Behav. 1997;21(2):131–154. doi:10.1023/A:1024956003661

61. Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(2):348–362. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

62. Fedor DB, Caldwell S, Herold DM. The effects of organizational changes on employee commitment: a multilevel investigation. Pers Psychol. 2006;59(1):1–29. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00852.x

63. James LR, Demaree RG, Wolf G. Rwg: an assessment of within-group interrater agreement. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(2):306–309. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.306

64. Bliese PD. Within-group agreement, non-Independence, and reliability: implications for data aggregation and analysis. In: Klein KJ, Kozlowski SWJ, editors. Multilevel Theory, Research and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions and New Directions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000:349–381.

65. Hirst G, Knippenberg DV, Chen CH, Sacramento CA. How does bureaucracy impact individual creativity? A cross-level investigation of team contextual influences on goal orientation-creativity relationships. Acad Manage J. 2011;54(3):624–641. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.61968124

66. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical Considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

67. Shen J, Tang N, D’Netto B. A multilevel analysis of the effects of HR diversity management on employee knowledge sharing: the case of Chinese employees. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2014;25(12):1720–1738. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.859163

68. Zhang Y, Lepine JA, Buckman BR, Wei F. It’s not fair…or is it? The role of justice and leadership in explaining work stressor-job performance relationships. Acad Manage J. 2014;57(3):675–697. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.1110

69. Hofstede G. The interaction between national and organizational value systems. J Manage Stud. 1985;22(4):347–357. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.1985.tb00001.x

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.