Back to Journals » Infection and Drug Resistance » Volume 12

A community-acquired lung abscess attributable to odontogenic flora

Authors Guo W, Gao B, Li L, Gai W, Yang J, Zhang Y, Wang L

Received 10 June 2019

Accepted for publication 16 July 2019

Published 8 August 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 2467—2470

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S218921

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Suresh Antony

Wenjia Guo,1 Bo Gao,1 Li Li,1 Wei Gai,2 Jianghui Yang,3 Yan Zhang,2 Lijun Wang4

1Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital, School of Clinical Medicine, Tsinghua University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 2National Engineering Research Center for Beijing Biochip Technology, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 3Department of Pathology, Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital, School of Clinical Medicine, Tsinghua University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 4Clinical Research Center, Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital, School of Clinical Medicine, Tsinghua University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Abstract: A lung abscess is an infectious pulmonary disease characterized by pus-filled cavity formation and often an air-fluid level. In this article, we described an indolent community-acquired lung abscess suspected as a tumor previously. A 56-year-old male presented with cough and expectoration for 2 months and hemoptysis for 2 weeks. His physical examinations, whole blood count and C-reactive protein level were normal. The chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 40×38×39 mm high-density mass in the right upper pulmonary lobe, with irregular borders. The pathology of a CT-guided percutaneous needle aspiration biopsy showed numerous inflammatory cells and bacteria infiltration without tumor lesions. Bacteriological detection of lung tissue revealed the cause was odontogenic flora. A next-generation sequencing demonstrated the etiologic correlation between lung abscess and periodontitis. After a 2-month pathogen-directed oral antibiotics therapy combined with chlorhexidine gargle oral care, this patient showed a remarkable improvement. Periodontitis can be a cause of a lung abscess, which would be taken into account in the treatment regimes preventing infectious recurrence.

Keywords: community-acquired lung abscess, periodontitis, odontogenic flora

Introduction

A lung abscess is an infectious pulmonary disease characterized by pus-filled cavity formation and often an air-fluid level. Primary lung abscesses are often polymicrobial and contain multiple anaerobic species.1 The bacteriological characteristics, however, have gradually changed. Klebsiella pneumoniae2,3 was reported as the most common organism in lung abscess cases in Asia, moreover, in alcoholics with poor oral hygiene, the spectrum of pathogens contains Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes and Actinomyces. Thus, etiology diagnosis cannot be ignored. On the other hand, the most common predisposing factor was an unhygienic oral cavity.2 Nevertheless, the impact of dental diseases on lung abscess is often underestimated in routine clinical practice. Here, we describe a case of indolent community-acquired lung abscess (CALA) due to odontogenic flora.

Case presentation

A 56-year-old male complained of cough and expectoration for 2 months and hemoptysis for 2 weeks. He reported no fever, dyspnea, chest pain or distress. On physical examination, his temperature was 36.5°C, heart rate 72 bpm, blood pressure 127/72 mmHg and oxygen saturation 98% when he was breathing ambient air. His breath sounds were clear without rales. The laboratory tests revealed white blood cell count was 8.48×109 cell/L, containing 64.3% neutrophils, 26.8% lymphocytes and 7.5% monocytes. The C-reactive protein was 6 mg/L within a normal range. The chest computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) showed a 40×38×39 mm high-density mass in the right upper pulmonary lobe, with irregular borders. As a result, lung cancer was suspected. Then, we performed a CT-guided percutaneous fine-needle aspiration biopsy in order to identify either tumor or infection. The patient suffered from fever and the serum procalcitonin increased to 3.42 ng/mL after aspiration. The patient had underlying diseases, including diabetes mellitus and hyperlipemia. He had about 30-year history of smoking or alcohol consumption, and he quitted smoking 7 years ago.

|

Figure 1 A chest computed tomography (CT) scan on admission demonstrated a high-density 40×38×39 mm mass on the right upper lung lobe, with irregular borders. |

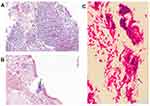

Bacteriological detection of expectorated sputum samples yielded no pathogens with routine aerobic culture. However, Gram stain of the lung biopsy suggested a variety of bacteria (Figure 2C); then, tissue culture detected moderate Fusobacterium nucleatum and Parvimonas micra. In addition, the pathology showed significant inflammatory cells and bacteria infiltration without tumor lesions (Figure 2A and B). Thus, the diagnosis of a community-acquired pulmonary abscess was concluded.

Since the isolated pathogens are oral cavity microbiome constitute, we further performed the oral examination and dental orthopantomography (Figure 3). The patient had severe chronic periodontitis.

|

Figure 3 Several odontolith with high-density on dental orthopantomography. |

The antibiotics regimes are metronidazole (0.4 g, tid) and oral amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium (1 mg/0.5 mg, tid) for 2 months. At the same time, oral care with chlorhexidine gargle was advocated every day. After therapy, the mass decreased remarkably (Figure 4). Now, the patient was recovered.

|

Figure 4 Chest CT showed a significantly decreased lung mass lesion after 2-month therapy.Abbreviation: CT, computed tomography. |

Next-generation sequencing (NGS)

A NGS of both the lung tissue and odontolith was performed by National Engineering Research Center for Beijing Biochip Technology, in order to explore the correlation between periodontitis and lung abscess.

Multiple anaerobic bacteria genomes were found in the lung tissue and listed in Table 1, comprising of Porphyromonas gingivalis, P. micra, F. nucleatum, Tannerella forsythia and Treponema species. Our bacteriological culture coincides with NGS results. Moreover, the NGS results from odontolith were generally consistent with lung tissue (Table 2), including T. forsythia, P. gingivalis and Treponema species. The NGS confirmed the etiologic correlation between lung abscess and periodontitis.

|

Table 1 The next-generation sequencing (NGS) from the lung tissue |

|

Table 2 The next-generation sequencing (NGS) from the odontolith |

Discussion

Classically, lung abscess could be classified into aspiration lung abscess, secondary lung abscess and hematogenous lung abscess, while aspiration pneumonia could be the most common cause.4 Actually, anaerobes comprise 60–80% of lung abscess etiologic pathogens.1 Dental diseases such as gingivitis usually provide the inoculums in which large quantities of anaerobic bacteria are colonized and then spread into lung to develop aspiration lung abscess. Takayanagi5 investigated the etiologic pathogens of CALA in Japan. It indicated that periodontal disease was highly present in 61% of these patients with lung abscess. Meanwhile, alcohol ingestion was the most important risk factor.2 In our case, the patient not only had a history of alcohol consumption and a severe periodontitis, but also most of the pathogens in odontolith can be found in the abscess lesion. Thus, chronic periodontitis is likely to be a cause for lung abscess in this patient.

Previously, mainly bacterial cultures of sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid had been used to identify the etiology of lung abscess. Due to the contamination of oral flora, the etiology could not be clarified in many cases.1 Percutaneous aspiration biopsy is a promising method at a time when majority clinicians have ignored performing any bacteriological tests in cases of pulmonary infection. The differential diagnosis in this patient just benefits from the aspiration biopsy. Since lung abscesses are often mixed infection, conventional bacterial culture is challenging to recover all the pathogens. Until the last decade, a new class of sequencing platforms defined “Next Generation Sequencing” (NGS) technologies has been developed and applied for the identification of pathogens in clinical material.6 Recently a blinded, prospective cohort study7 was published to evaluate the value of NGS in patients with suspected infection. As a result, NGS provided a high negative predictive value with 96±5%. Moreover, the detection rates of pathogens with NGS were significantly higher than that with conventional methods (36% vs 11%). To further determine the origin of pathogens, NGS technology with both biopsy tissue and odontolith were utilized and odontogenic flora were confirmed as the pathogens. To our knowledge, it is the first report that a patient with odontogenic CALA was confirmed by NGS. The sequencing could make potentially contributions to mixed infection, especially exploring the source of the infection to make effective strategy.8

In case of etiology of lung abscess is clear, targeting therapy would be cost-effective. In general, all anaerobes isolated from the respiratory samples are susceptible to beta-lactam/beta-lactamase combinations such as amoxicillin-clavulanate. After 2-month oral antibiotics, amoxicillin-clavulanate and metronidazole, combined with chlorhexidine gargle oral care, this patient showed a remarkable improvement.

Conclusion

Dental diseases can be a cause of a lung abscess, which is often easily overlooked. Then, dental treatment is as significant as antibiotics in the therapy of lung abscess with chronic periodontitis. Finally, NGS will be a promising method for microbiological diagnosis and tracking trace in patients with infection.

Abbreviations

CALA, community-acquired lung abscess; NGS, next-generation sequencing technology.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital approved the study procedure. The reference number of the approval is 19117-0-01. The patient provided a written informed consent for the case details to be published.

Availability of data and material

All the related data are presented in the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bartlett JG. The role of anaerobic bacteria in lung abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:923–925. doi:10.1086/428586

2. Mohapatra MM, Rajaram M, Mallick A. Clinical, radiological and bacteriological profile of lung abscess – an observational hospital based study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6:1642–1646. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2018.374

3. Wang JL, Chen KY, Fang CT, Hsueh PR, Yang PC, Chang SC. Changing bacteriology of adult community-acquired lung abscess in Taiwan: Klebsiella pneumoniae versus anaerobes. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:915–922. doi:10.1086/428574

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, Browne AS, Pratter MR. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217–221. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Takayanagi N, Kagiyama N, Ishiguro T, Tokunaga D, Sugita Y. Etiology and outcome of community-acquired lung abscess. Respiration. 2010;80:98–105. doi:10.1159/000312404

6. Deurenberg RH, Bathoorn E, Chlebowicz MA, et al. Application of next generation sequencing in clinical microbiology and infection prevention. J Biotechnol. 2017;243:16–24. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.12.022

7. Parize P, Muth E, Richaud C, et al. Untargeted next-generation sequencing-based first-line diagnosis of infection in immunocompromised adults: a multicentre, blinded, prospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23:574 e1–e6. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.006

8. Besser J, Carleton HA, Gerner-Smidt P, Lindsey RL, Trees E. Next-generation sequencing technologies and their application to the study and control of bacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:335–341. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.10.013

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.