Back to Journals » Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine » Volume 7

A 5-year trend of Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence among dyspeptic patients at Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia

Authors Workineh M , Andargie D

Received 29 January 2016

Accepted for publication 19 April 2016

Published 8 July 2016 Volume 2016:7 Pages 17—22

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RRTM.S105361

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Thomas Unnasch

Meseret Workineh,1 Desalegn Andargie2

1Immunology and Molecular Biology, School of Biomedical and Laboratory Sciences, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, 2University of Gondar Teaching Hospital, Gondar, Ethiopia

Background: Helicobacter pylori infection is a major public health problem affecting half of the world’s population. The prevalence of H. pylori varies in different societies and geographical locations. Thus, timely information on H. pylori epidemiology is critical to combat this infection. This study aimed to determine the seroprevalence and trend of H. pylori infection over a period of 5 years among dyspeptic patients at Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods: A retrospective analysis of consecutive dyspeptic patients’ records covering the period between January 2009 and December 2013 was conducted. The hospital laboratory generated the data by a serological method of detecting the antibodies for H. pylori from serum by a one-step rapid test device. Chi-square analysis was used to identify significant predictors. A P-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results: Among all the study subjects, 2,733 (41.6%) were found to be seropositive. The seroprevalence was significantly higher in males (43.2%) than in females (39.9%) (χ2=9; P=0.002). In terms of age groups of the patients, high rates of H. pylori were found among the participants older than 60 years (57%) (χ2=36.6; P≤0.00001). The trend analysis of H. pylori prevalence revealed a fluctuating prevalence; it was 44.5% in the year 2009 and decreased to 34% and 40% in the years 2010 and 2011, respectively. However, there was an increment to 52.5% in the year 2012, and then it decreased to 30.2% in the year 2013.

Conclusion: This study showed high seroprevalence of H. pylori among the dyspeptic patients in Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital. The trend of the seroprevalence varied from year to year in the 5 consecutive years. Considering this, designing appropriate prevention and control strategies is mandatory.

Keywords: H. pylori infection, dyspeptic patients, seroprevalence, Ethiopia

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection is one of the commonest bacterial infections affecting more than half of the world’s population.1 H. pylori is a microaerophilic gram-negative, spiral, flagellated bacterium with a capability of abundant urease production, which has been implicated in several upper gastrointestinal diseases, such as dyspepsia.2,3 H. pylori is the cause for duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, and nonulcer dyspepsia.4,5 H. pylori infection is also found to be associated with the development of gastric cancer.6,7

H. pylori causes more than half of peptic ulcers worldwide.8 The bacterium causes peptic ulcers by damaging the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum, which causes the stomach acid to get through to the sensitive lining layer. Together, the stomach acid and H. pylori produce irritation in the lining of the stomach or duodenum and cause an ulcer.9

H. pylori is found in all parts of the world, although the prevalence is higher in developing countries than developed countries. Approximately 50% of the population in developed countries is known to be infected with H. pylori. This percentage increases to 80% in developing countries.10–12 This high prevalence of H. pylori infection has been attributed to many factors such as poor socioeconomic status, hygienic practice, and overcrowding. H. pylori infection is generally acquired during childhood and persists lifelong in the absence of antibiotic treatment. However, H. pylori infects all age groups, although the infection is more prevalent in adult population than children.13,14

H. pylori prevalence varies considerably between populations, geographical areas, and time of the study. The epidemiology of H. pylori in Ethiopia shows remarkable variations with regions, study population, and period of study.15–17 In our study area, there was no study conducted that shows the trend of prevalence of H. pylori infection. Therefore, in this study, we sought to explore the trend of the seroprevalence of H. pylori infection among dyspeptic patients who attended the Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital in five consecutive years and to identify sociodemographic determinants for H. pylori seropositivity.

Methods

Study design and area

This retrospective study was conducted at Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Bahir Dar is the capital city of Amhara region and situated on the southern shore of Lake Tana, which is the source of the Blue Nile. The city is located ∼565 km far from Addis Ababa. Geographically, the city has an altitude of 8° and a longitude of 11° 36″N and 37° 25″E and an evaluation of 1,840 masl and has an average temperature of 25°C. The hospital provides different inpatient and outpatient services for ∼5–7 million people per year in Northwest Ethiopia. The study was conducted in the serology laboratory of the hospital.

Study population

All dyspeptic patients who were suspected for H. pylori infection and visited the serology laboratory of Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital for H. pylori test from January 2009 to December 2013 were included in this study. The majority of patients had dyspeptic symptoms, including epigastric pain or burning, early satiety, nausea, belching, and bloating.

Data collection

A total of 6,566 subjects whose data were completely registered were included in the study. Five-year data from January 2009 to December 2013 were taken from the serology log book in Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Sociodemographic characteristics (age and sex) of the study subjects were collected using a checklist.

Detection of H. pylori infection

The hospital laboratory generated the data by a serological method of detecting the antibodies for H. pylori from serum or plasma. Anti-H. pylori antibodies of all isotopes (IgG, IgM, and IgA) against H. pylori were detected by a one-step rapid test device (dBest H. pylori test strip, Ameritech, USA). Appearance of color band on the device on both test line and control line was interpreted as positive and as negative if it is only on the control line.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered on Epi Info™ Version 5.3.1, and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 20. Completeness of the data collected was checked, and the frequency distribution of variables was done. Chi-square test was used to test for the presence of association between prevalence of H. pylori and sociodemographic variables. Statistical significance was defined as P-value of <0.05.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the ethical committee of School of Biomedical and Laboratory Sciences, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, and University of Gondar, which deemed that patient written informed consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study. An official letter was obtained from the diagnostic director of Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital to collect the data. All patient data were kept confidential.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

A total of 6,566 dyspeptic patients were screened for H. pylori at Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital from January 2009 and December 2013. Of the 6,566 study participants, 3,020 (46%) were males and 3,546 (54%) were females, with a male-to-female ratio of 0.85:1. The majority of clients were young adults in the age range of 21–40 years (56%) (Table 1).

| Table 1 Overall seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori among dyspeptic patients in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital from January 2009 to December 2013 |

Prevalence of H. pylori infection among the study subjects

Overall, 41.6% (2,733/6,566) of the study participants were found to be H. pylori seropositive. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was higher in males than in females (43.6% vs 39.9%). The differences between H. pylori seropositivity of male and female subjects were statistically significant (χ2=9; P=0.002). The prevalence of H. pylori was higher among the participants in the age group of >60 years (57%), and the lowest seropositivity was observed in the age group of <20 years (39.6%). The differences between H. pylori seropositivity among different age groups of the subjects were statistically significant (χ2=36.6; P≤0.00001) (Table 1).

Trend analysis of H. pylori in five consecutive years

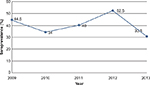

The seroprevalence of H. pylori infection among the dyspeptic patients in Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital in the year 2009 was 44.5%. The seroprevalence decreased to 34% and 40% in the years 2010 and 2011, respectively. However, there was a high increment on the seroprevalence in the year 2012 (52.5%). The seroprevalence decreased again in the year 2013 (30.2%). Generally, in this study, we found high but fluctuating prevalence of H. pylori infection among dyspeptic patients (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Trend of seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori among dyspeptic patients during 5-year period at Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. |

Sex-specific trend of prevalence of H. pylori among dyspeptic patients

Regarding the sex-specific prevalence of H. pylori, of the 467 male clients examined for H. pylori in 2009, 225 (48%) were positive, and of the 569 female clients examined in the same year, 236 (41.5%) were found to be positive. This higher prevalence found in males than in females in this year was statistically significant (χ2=4.5; P=0.034). Similarly, the seroprevalence was significantly higher in males (55%) than females (50%) in the year 2012 (χ2=5.71; P=0.01). However, the seroprevalence of H. pylori in the year 2013 was significantly higher in females (34.5%) than in males (24.3%) (χ2=13; P=0.0002) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

| Table 2 Year-specific percent distribution on seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori among dyspeptic patients by sex at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital from January 2009 to December 2013 |

| Figure 2 Trend of Helicobacter pylori seropositivity among dyspeptic patients at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital over 5 years (2009–2013) by sex of subjects. |

Discussion

H. pylori infection is one of the commonest infections affecting more than half of the world’s population and it is highly prevalent in developing countries.1 H. pylori is highly prevalent in Ethiopia. Nevertheless, H. pylori epidemiology in the country varies markedly in prevalence and risk factors from place to place. Therefore, accurate and timely data on the local epidemiology of H. pylori are a necessity to tailor intervention strategies accordingly. This study sought to update the trend seroprevalence of H. pylori infection among dyspeptic patients during the 5-year period at Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia.

The overall prevalence of H. pylori observed in our study was 41.6%. This was lower than the earlier report of prevalence of 56% for H. pylori in the study area.16 The low prevalence in this study may be attributed to improvement in environmental sanitation. Similarly, the prevalence we found in this study was lower than the previously reported 89% rate from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia,15 87% in Ugana,18 65% in Tanzania,19 63.5% in Nigeria,20 80.5% in Kenya,21 and 75.4% in Ghana.22 The difference in the prevalence might be due to diverse contributing factors including socioeconomic status, geographical or living conditions, as well as ethnicity or location of each population.

However, the prevalence of H. pylori obtained in this study was higher than the prevalence reported in Japan (34.9%),23 Canada (23.1%),24 and the US (9.4%).25 The difference in prevalence could be due to variations in the socioeconomic status, the level of environmental sanitation, and difference in hygiene conditions. The other possible explanation for the higher prevalence of H. pylori infection found in our study may be due to the test method we used. We used serology for the detection of H. pylori in serum, which might show the exaggeration of the actual prevalence since serology cannot differentiate current infection from past infection.

In this study, we found varied seroprevalence of H. pylori infection in 5 years. The prevalence fluctuates from year to year. Generally, it seems decreasing since the prevalence was 44.5% in 2009 and decreased to 30.2% in 2013. In line with our findings, several studies from Iran, South Korea, and Kuwait showed that the prevalence of H. pylori has declined in recent years.26–28 There might be various reasons for decrement in the prevalence of H. pylori infection. The elimination of H. pylori infection as a result of other antibiotic treatments in occasion of concomitant bacterial and parasitic diseases might be one factor. In addition to this, the decrement in trend prevalence might be related to the human host factors as well as socioeconomic and hygiene factors.

Several studies showed conflicting findings about the association of H. pylori infection and age of the patients. Studies conducted in the People’s Republic of China29 and Bhutan30 reported that there is no statistically significant association between age of the patients and H. pylori infection. However, several other studies conducted elsewhere found a significant association between age of the patients and the prevalence of H. pylori infection.31–33 Consistent with the earlier studies, this study found an increase in the prevalence of H. pylori infection as age of the patients increases. This increase in prevalence with age may be attributed to the laboratory technique we used. We used serology to identify the H. pylori infection. Therefore, the high prevalence with increasing age may reflect the persistence of anti-H. pylori antibodies from previous infection rather than indication of current infection in endemic areas. It is found that the IgG antibody of the seroprevalence assay lasts for up to 3.5 years or more in the serum even after the organism has been eradicated.34

The role of sex as a risk factor for H. pylori infection is much argued. Some studies found no association between sex and H. pylori infection,35,36 and some others reported female predominance.37,38 However, in this study, we found a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection in males compared to females. Similar to our current findings, many other studies found higher prevalence in males compared to females.39–41 Thus, this may explain why peptic ulcer diseases and gastric cancers, which are the diseases that have high association with H. pylori infection, occur predominantly in males.

Conclusion

This study showed high but fluctuating seroprevalence of H. pylori among the dyspeptic patients in five consecutive years. Patients who were >60 years of age and males were found to be more vulnerable groups. Considering this, our current study necessitates further community-based cross-sectional study to examine the burden of the infection in the community in general, and designing appropriate prevention and control strategies is mandatory.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the serology laboratory staff at the Bahir Dar Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital for their invaluable support during data collection.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Megraud F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993;22(1):73–88. | ||

Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(15):1175–1186. | ||

Ahmed N. 23 years of the discovery of Helicobacter pylori: is the debate over? Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2005;4:17. | ||

Ruggiero P. Helicobacter pylori and inflammation. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(38):4225–4226. | ||

Sachs G, Scott DR, Wen Y. Gastric infection by Helicobacter pylori. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13(6):540–546. | ||

Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process – first American Cancer Society Award lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52(24):6735–6740. | ||

De Sablet T, Piazuelo MB, Shaffer CL. Phylogeographic origin of Helicobacter pylori is a determinant of gastric cancer risk. Gut. 2011;60(9):1189–1195. | ||

Kuster JG, Vanviret AH, Kulpers EJ. Pathogenesis of H. pylori infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(3):449–449. | ||

Yamada T, Searle JG, Ahnen D, et al. Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcer Disease. JAMA. 1994;272(1):65–69. | ||

Bures J, Kopacova M, Skodov-Fendrichova M. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Vnitr Lek. 2011;57(12):993–999. | ||

Torres J, Leal-Herrera Y, Perez-Perez G. A community based seroepidemiologic study of Helicobacter pylori infection in Mexico. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(4):1089–1094. | ||

Hunt RH, Xiao SD, Megraud F, et al; World Gastroenterology Organization. Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline. J Gastroenteroin Liver Dis. 2011;20(3):299–304. | ||

Ally R, and Segal I. H. pylori Infection-Acquisition in Children. QJM. 2001;94(10):561–565. | ||

Pelser H, Househam K, Joubert G. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori antibodies in children in Bloemfontein, South Africa. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24(2):135–139. | ||

Desta K, Asrat D, Derbie F. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among health blood donors in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:501–506. | ||

Tadege T, Mengistu Y, Desta K, Asrat D. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in and its relationship with ABO Blood groups. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2005;19(1):55–60. | ||

Feleke M, Afework K, Getahun M. Seroprevalence of H. pylori in dyspeptic patients and its relationship with HIV infection, ABO blood groupings and life style in GUH. World J Gastroenol. 2006;12:1957–1961. | ||

Newton R, Ziegler J, Casabonne D, et al; Uganda Kaposi’s Sarcoma Study Group. Helicobacter pylori and cancer among adults in Uganda. Infect Agent Cancer. 2006;7(1):5. | ||

Ayana SM, Swai B, Maro VP, Kibiki GS. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic findings and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among adult patients with dyspepsia in northern Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2014;16(1):16–22. | ||

Abiodun C, Jesse A, Samuel O, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori among Nigerian patients with dyspepsia in Ibadan. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;6:18. | ||

Ogutu EO, Kang’ethe SK, Nyabola L, Nyong’o A. Endoscopic findings and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Kenyan patients with dyspepsia. East Afr Med J. 1998;75(2):85–89. | ||

Baako BN, Darko R. Incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Ghanaian patients with dyspeptic symptoms referred for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. West Afr J Med. 1996;15(4):223–227. | ||

Fujisawa T, Kumagai T, Akamatsu T, Kiyosawa K, Matsunaga Y. Changes in seroepidemiological pattern of Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis A virus over the last 20 years in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(8):2094–2099. | ||

Naja F, Kreiger N, Sullivan T. Helicobacter pylori infection in Ontario: prevalence and risk factors. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21(8):501–506. | ||

Jackman RP, Schlinchting C, Carr W, Dubois A. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in United States navy submarine crews. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134(3):460–464. | ||

Farshad S, Japoni A, Alborzi A, Zarenezhad M. Changing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in south of Iran. Iran J Clin Infect Dis. 2010;5(2):65–69. | ||

Yim JY, Kim N, Choi SH, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter. 2007;12(4):333–340. | ||

Alazmi WM, Siddique I, Alateeqi N, Al-Nakib B. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among new outpatients with dyspepsia in Kuwait. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:14. | ||

Zhang B, Hao GY, Gao F, et al. Lack of association of common polymorphisms in MUC1 gene with Helicobacter pylori infection and non-cardia gastric cancer risk in a Chinese population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(12):7355–7358. | ||

Dorji D, Dendup T, Malaty HM. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in Bhutan: the role of environment and geographic location. Helicobacter. 2013;19(1):69–73. | ||

Wizla-Derambure N, Michaud L, Ategbo S, et al. Familial and community environmental risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33(1):8–63. | ||

Malaty M, El-Kasabany A, Graham Y. Age at acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection: a follow-up study from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2002;359(9310):931–935. | ||

Granstrom M, Tindberg Y, Blennow M. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in a cohort of children monitored from 6 months to 11 years of age. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(2):468–470. | ||

Cutler AF, Prasad VM, Santogade P. Four-year trends in Helicobacter pylori IgG serology following successful eradication. Am J Med. 1998;105(1):18–20. | ||

Rasheed F, Ahmad T, Bilal R. Frequency of Helicobacter pylori infection using 13C-UBT in asymptomatic individuals of Barakaho, Islamabad, Pakistan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2011;21(6):379–381. | ||

Petrović M, Artiko V, Novosel S, et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection estimated by 14C-urea breath test and gender, blood groups and rhesus factor. Hell J Nucl Med. 2011;14(1):21–24. | ||

Zevit N, Niv Y, Shirin H, Shamir R. Age and gender differences in urea breathe test results. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41(7):767–772. | ||

Rehnberg-Laiho L, Rautelin H, Valle M, Kosunen TU. Persisting Helicobacter antibodies in Finnish children and adolescents between two and twenty years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17(9):796–799. | ||

Brown LM, Thomas TL, Ma JL, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in rural China: demographic, lifestyle and environmental factors. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(3):638–645. | ||

Mayr M, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Wick G, Xu Q. Infections, immunity, and atherosclerosis: associations of antibodies to Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, and cytomegalovirus with immune reactions to heat-shock protein 60 and carotid or femoral atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2000;102(8):833–839. | ||

Akin L, Tezcan S, Hascelik G, Cakir B. Seroprevalence and some correlates of Helicobacter pylori at adult ages in Gulveren Health District, Ankara, Turkey. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132(5):847–856. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.