Back to Journals » Infection and Drug Resistance » Volume 16

6084 Cases of Adult Tetanus from China: A Literature Analysis

Authors Gou Y , Li SM , Zhang JF , Hei XP, Lv BH , Feng K

Received 13 January 2023

Accepted for publication 28 March 2023

Published 4 April 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2007—2018

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S404747

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Héctor Mora-Montes

Yi Gou,1,2,* Sheng-Ming Li,1,2,* Jun-Fei Zhang,1,2 Xiao-Ping Hei,2 Bo-Hui Lv,1,2 Ke Feng2

1Department of Emergency Medical, General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University, Yinchuan, Ningxia, 750000, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Clinical Medicine, Ningxia Medical University, Yinchuan, Ningxia, 750000, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Ke Feng, Department of Emergency Medical, General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University, 804 Shengli South Street, Xingqing District, Yinchuan, Ningxia, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 18709676586, Email [email protected]

Objective: To describe the clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of tetanus and determine the most appropriate focus for tetanus prevention and treatment to reduce morbidity and mortality in China.

Methods: Four databases, including the Chinese Bio-Medical Literature Database, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Scientific Journal Database, and Wan-fang Data, were searched from 1 January, 2000 to 30 October, 2022.

Results: In total, 151 articles including 6084 tetanus patients met the inclusion criteria. Additionally, 5925 patients had their gender recorded in detail, among which 66.67% (3950/5925) were male, and 33.33% (1975/ 5925) were female. The average age in the detailed records was reported in 4773 cases, with an overall average age of 46.69. The number of patients’ places of residence was 580. Those from rural areas comprised the highest percentage with 88.62% (514 / 580). The causes of injury were recorded in 1592 cases in total; injuries caused by metals, wood, and wooden spikes accounted for the highest percentage with 54.52% (868/1592). Patient outcomes were recorded in 4305 cases, with a mortality of 9.34% (402/4305). The leading causes of death included treatment terminated by family members, asphyxia due to persistent spasms, respiratory failure, and autonomic dysfunction, family automatic abandonment and asphyxia accounted for the highest percentage, both 24.00% (54/225).

Conclusion: The overall success rate of tetanus treatment in China has dramatically improved, but the prevention and control of non-neonatal tetanus is still challenging. Focus should be placed on the prevention of adult tetanus and standardizing the use of sedative and spasmolytic drugs. Additionally, medical professionals should popularize tetanus prevention and treatment knowledge among the people and strengthen training in grass-roots hospitals.

Keywords: tetanus, prevention, outcome, immunization

Introduction

Tetanus, which includes muscle spasms as its primary manifestation, is an acute specific infectious disease caused by tetanus bacillus invading the nervous system through exposure to wounds. Although this disease is rare in developed countries, it remains common in many low- and middle-income countries.1 The average morbidity of tetanus in the whole population of Africa is relatively high, ranging from 0.3010/100 000 to 0.5490/100 000; the average annual morbidity of tetanus in the United States was 0.01/100 000 from 2001 to 2008; and Australia had an incidence of 0.35 per million by 2002.2–4 The incidence of neonatal and childhood tetanus was significantly reduced in China since the country began implementing a childhood immunization program in 1978, but adult tetanus still occurs occasionally, and there is an absence of accurate studies on the incidence of tetanus among the general population in China. It was reported that tetanus mortality rates are as high as 16% to 52.6%, and the mortality rate can reach 65–70% in areas where intensive care is lacking.5–7 Tetanus, therefore, remains a serious public health problem responsible for around 60,000 deaths annually around the globe, with a reported 213,000–293,000 deaths worldwide, and seriously threatens people’s lives and health.8–10 The disease is fatal but can be prevented through vaccination, tetanus antitoxin (TT), or tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG) after trauma.11 There is a lack of epidemiological data on non-neonatal tetanus in China, but in some reports, certain hospitals admitted more than 30 tetanus patients in a year. Guangdong medical college admitted 72 cases in two years,12 Leizhou People’s Hospital admitted 60 cases in one year,13 and Luoding People’s Hospital admitted 90 cases in two and a half years.14 Thus, the current situation of non-adult tetanus prevention and control in China may be not optimistic. Under this background, the present study analyzed the literature on non-neonatal tetanus published from 2000 to 2020 in China to describe the clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of tetanus and determine the most appropriate focus for tetanus prevention and treatment to reduce morbidity and mortality in China.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Methods

Four databases, including the Chinese Bio-Medical Literature Database, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Scientific Journal Database, and Wan-fang Data, were searched from 1 January, 2000 to 30 October, 2022;“tetanus” was the search term used. Two researchers independently screened the literature according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a senior tetanus expert made discriminations in case of disagreement. Data were extracted using Excel 2019 and mainly included clinical data such as the paper title, publication unit, publication time, case source period and province, number of cases, case sex and age, incubation period, occupation, place of residence, the severity of tetanus, causes of injury, the status of tetanus immunization 24 h after injury, the situation of wound management 24 h after injury, treatment, and outcome. For literature whose cases came from the same period in the same hospital, and in instances where the same case was repeatedly reported in different journals, we selected only one article. For patients in critical condition, the termination of treatment by family members was considered death.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) the subjects had non-neonatal tetanus; (2) general data, such as the number of cases, gender, and age, were basically complete in the reports. Exclusion criteria: (1) reviews and case reports; (2) the sources of patients were not clear; (3) cases were recorded before the year 2000; (4) the subjects had neonatal tetanus.

Statistical Methods

Data were collated, organized, and summarized using Excel 2019. Quantitative data were expressed as the mean, and qualitative data were expressed as frequency. The composition ratio, mortality rate, and tracheotomy (T) rate were calculated for each group of cases.

Results

Description of the Included Literature

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total number of 151 papers, in which the number of tetanus patients added up to 6084, were included from 128 hospitals in 25 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities, covering both clinical and nursing studies. The top three groups of tetanus cases were in Hebei Province (10.47%) (637/6084), Guangdong Province (10.21%) (621/6084), and Shandong Province (9.34%) (568/6084). Among 128 hospitals, the numbers of tertiary hospitals, secondary hospitals, infectious disease hospitals, and other hospitals were 93, 16, 12, and 7, respectively. Among the 151 articles, clinical and nursing studies accounted for 56.29% (85/151) and 43.71% (66/151), respectively, and literature focusing on severe tetanus accounted for 47.02% (71/151). The distribution of tetanus patients is shown in Figure 1.

Description of Included Tetanus Cases

(1) Among 6084 tetanus patients, 5925 patients had their gender recorded. In total, 3950 were male, and 1975 were female, accounting for 66.67% (3950/5925) and 33.33% (1975/ 5925), respectively. (2) The total number of cases recording age was 5204, with ages ranging from 1 to 100 years. Average ages were recorded in 4773 cases, with an overall average age of 46.69 years old. The minimum and maximum average ages were 25.00 and 65.22 years old, respectively. (3) In total, 580 patients had their places of residence recorded. Patients from rural areas occupied the highest percentage with 88.62% (514 / 580). Occupations were recorded in 645 cases, with farmer being the most common, accounting for 83.57% (539/645). (4) The total incubation period was recorded in detail in 2024 cases; 1 and 120 d were the shortest and longest incubation periods, respectively. In summary, the average incubation period was recorded in 1511 cases, and the total incubation period was 11.04 d on average. (5) In total, 4034 cases recorded a severity grading, the proportions of I & II and III & IV were found in 30.17% (1217/4034) and 69.83% (2817/4034) of cases, respectively, as shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 General Information About the Cases |

Circumstances of Injury

Causes of Injury

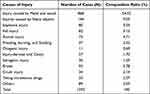

A total of 3513 cases recorded the circumstances of injury. Causes of injury were unknown in 162 cases, and 60 patients presented atypical trauma, accounting for 4.61% (162/3513) and 0.85% (60/3513), respectively. The causes of injury were recorded in 1592 cases in total; injuries caused by metals, wood, and wooden spikes, such as rusty nails and iron pieces, accounted for the highest percentage with 54.52% (868/1592), followed by sharp objects such as glass and knives, accounting for 9.05% (144/1592). Others included firecracker explosions, falls, animal injuries, freezing, burning, and scalding, as shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Causes of Injury |

Injury Sites and Wound Management 24h After Injury

The total number of injury sites was recorded in 1258 cases. The lower extremities comprised the highest percentage, accounting for 54.35% (699/1258), followed by the upper extremities with 36.47% (469/1286). The head and neck and trunk accounted for a smaller portion, as shown in Figure 2.

The overall amounts of wound management 24 h after injury were recorded in 775 cases. In total, 87.74% (680/775) of patients did not deal with their wounds 24 h after injury, a small number of patients dealt with their wounds by themselves, and a minimal number of patients sought formal wound treatment in the hospital, as shown in Figure 3.

Approach to Toxin Neutralization

The total number of papers detailing the approach to toxin neutralization was 54, covering 48 hospitals of different levels and 2036 cases. The methods of toxin neutralization included using TAT alone, TAT after desensitization after a positive TAT skin test, TIG after a positive TAT skin test, TIG alone, and a combination of TIG with TAT. Using TAT alone comprised the highest proportion, accounting for 57.12% (1163/2036), followed by TIG after a positive TAT skin test (15.32%), as shown in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Approach to Toxin Neutralization |

Therapies of Sedation and Spasmolysis

The overall number of cases detailing therapies using sedation and spasmolysis was 2488; the therapies used most frequently were diazepam, hibernation mixture, and midazolam alone, accounting for 14.83% (369/2488), 13.38% (333/2488), and 7.03% (175/2488), respectively. Dual therapies included a combination of diazepam with phenobarbital, diazepam with hibernation mixture, and a combination of propofol with magnesium sulfate, accounting for 13.87% (345/2488), 11.17% (278/2488), and 5.14% (128/2488), respectively. Triple and quadruple therapies were also not in the minority, as shown in Table 4.

|

Table 4 Therapies of Sedation and Spasmolysis |

Outcome and Tracheotomy

The 4305 cases with detailed records of patient outcomes were named the “contrast group”, including 402 deaths and a mortality rate of 9.34% (402/4305), with a tracheotomy rate of 30.59% (1317/4305). The 2749 cases in the control group with detailed tracheotomy records were named the “contrast tracheotomy group”, which included 222 deaths and a mortality rate of 8.08% (222/2749), with a tracheotomy rate of 47.91% (1317/2749). The leading causes of death included treatment terminated by family members, asphyxia due to persistent spasms, respiratory failure, and autonomic dysfunction. Treatment terminated by family members and asphyxia accounted for the highest percentage, with both at 24.32% (54/222), followed by respiratory failure at 22.07% (49/222), as shown in Figure 4.

A total of 3519 cases included detailed recorded of a tracheotomy; the tracheotomy rate was 58.42% (2056/3519). The overall number of patients in the “normal study group” (see Table 1 for the definition) with records of patient prognosis totaled 1977, including 224 deaths. The mortality was 11.33% (224/1977), the number of tracheotomies was 387, and the tracheotomy rate was 19.58% (387/1977); The total number of 1376 patients in the “normal study group” with records of patient outcomes and tracheotomies was named the “normal study group with tracheotomy”, which contained 120 cases of death and a mortality rate of 8.72% (120/1376), with 387 cases of tracheotomy and a tracheotomy rate of 28.13% (387/1376).

A total of 1269 cases in the “Critical care group” (see Table 1 for the definition) recorded outcomes, including 110 deaths, with mortality of 8.67% (110/1269), among which the tracheotomy rate was 60.52% (768/1269). The 931 cases in the“Critical care group” with records of outcomes and tracheotomies of patients were named the “Critical tracheotomy group”, including 75 cases of death; the mortality was 8.06% (75/931), and the tracheotomy rate was 82.49% (768/931). A comparison is shown in Table 5.

|

Table 5 Outcome and Tracheotomy |

Discussion

Case Analysis

In this study, the total number of non-neonatal tetanus cases in the past 20 years was 6084. In 9 out of 34 provincial administrative regions in China, the number of tetanus cases was unclear. Cases were limited to 1~5 hospitals in these provinces, so the actual number of cases may be higher. Although China was validated as having eliminated maternal and neonatal tetanus in 2012,15 the control situation of non-neonatal tetanus in China was found in this study to be dire, and more attention should be paid to reducing the morbidity of this disease. According to the survey, the percentage of males suffering tetanus (66.67%) was greater than females (33.33%), similar to the results in the studies of S Anuradha, Sam Olum, and Surabhi GS16–18 but less than the results in the study of Ananda.19 The higher prevalence in males may be related to the fact that males are often engaged in manual outdoor work such as agricultural and technical labor, which has a higher likelihood of injury. Conversely, the lower incidence in females may be associated with the factor that females are usually engaged in light physical labor and receive immunizations during pregnancy.20 Patient occupation is, overall, a significant risk factor for tetanus. In this study, the proportion of farmers was as high as 83.56%, and the proportion of people living in rural areas was as high as 88.62%, which are higher than the results of other researches. For example, Zhee Fan reported 47.0%,10 and Dr. K.V.L. Sudha Rani reported 28.65%.21 However, our results are similar to those of AHM FEROZ, who reported a value of 72.5%.22 The results showed that the leading groups of people suffering from tetanus are low-income workers, especially farmers and workers from rural areas, presumably because such workers are more likely to be exposed to the causal organism, in addition to the lack of necessary labor protection in agricultural production and work site activities, insufficient awareness of tetanus, and poor formal treatment of wounds after injury, which increase the risk of tetanus infection.23,24 In this study, most tetanus cases were among young and middle-aged people. The overall average age was 46.69 years, and those with an average age greater than 40 years accounted for 83.42%. The mean age of the 40~60-year-old population accounted for the highest percentage (80.03%). Compared to developed countries, the patients from China are younger. S. Tosun reported that most tetanus cases occurred during advanced age,5 62% were patients aged 65 years in a report Australia,3 and around 80% of the patients were 60 years of age in Japan.25 However, the mean age of patients is similar in Africa, with a mean age of 33.0 years in a report in Nigeria.26 Further, Amanuel Amare reported a mean age of 33.8 years in Ethiopia.27 The leading reasons for this situation are that the levels of tetanus antibodies and protection rates among people over 40 years old are low in China.28–30 Moreover, young people lack effective immunization programs and appropriate treatment for injuries in developing countries.21

Analysis of Circumstances of the Injury

In this study, the causes of injury were mainly common factors in life, such as being stabbed by nails and wood, cut by knives and glass, suffering firecracker explosions, and receiving animal bites;31–35 injury by metal and wood accounted for the highest percentage (54.52%). Other causes included road traffic accidents, burns, fissures of the foot, fall injuries, taking intravenous drugs, and post-surgical wounds.32,36,37 The causes of injury resembled those in other research, eg, in Southern India,38 Northwestern Tanzania,23 Ethiopia,27 and Turkey.5 There were also cases of atypical injuries such as abrasions,39 sole abrasions,40 stomatitis,33 otitis media,41 and paronychia.42 Thus, there is a possibility of tetanus as long as there is an open wound in the skin or mucous membrane, coupled with the presence of pollution, hypoxia, and a moist environment. In this study, 90.82% of Tetanus attacks were due to infection of the extremities, especially the lower extremities (54.35%), which is much higher than the value reported in Nigeria (lower limbs, 39.24%; upper limbs, 18.99%).43 This result is similar to a report in which the injuries on the lower limbs of patients totaled 48.75%, while the injuries on the upper limbs totaled 36.25%.22 These results differ from a report from India in which upper limb wounds were the most common (51.6%), followed by wounds on the lower limbs (38.3%).16 In total, 87.74% of patients in this study did not deal with their wounds 24 h after injury, and 9.30% of patients treated their wounds using home-based methods such as using a band-aid to stanch the wound after briefly applying alcohol44 and self-binding with Chinese herbal medicine,24,32 which can lead to incomplete disinfection and even create a polluted and oxygen-deprived environment. Furthermore, 96.66% of patients did not inject TAT or TIG,45,46 resulting in a significant increase in the risk of infection. This result is similar to some research in Bangladesh22 and India.16,21 It is evident that the injury site, wound management 24 h after injury, and causes of injury are significantly associated with patients’ occupations and places of residence. Daily factors of injury are common in agricultural work and industrial labor, so the affected population is mainly farmers, workers, and people in rural areas. The principal causes are insufficient knowledge of tetanus, poor hygiene attitudes and conditions, and little hospitalization consciousness. Additionally, most patients suffered minor injuries, so they did not take their wounds seriously In such cases, it is unlikely that patients will go to the hospital and be injected with tetanus immunoglobulin or tetanus antitoxin. This perception is one of the leading causes of why non-neonatal tetanus frequently occurs in developing countries, including China.

Analysis of Toxin Neutralization

As some studies have shown that TAT has a high probability of an allergic reaction (5%~30%), and the chance of an allergic reaction after desensitization remains 14.1%,47 some countries have banned TAT as a passive immunization agent against tetanus.48 However, the incidence of TIG allergies is only 0.2%,49 giving this drug the advantages of safety, easy clinical operation, low incidence of allergic reactions, a strong neutralizing effect on toxins, and longer protective and preventive effects than TAT.50 However, in this study, most hospitals, including tertiary hospitals, preferred using a tetanus antitoxin to strengthen passive immunity,51–53 and some hospitals continued to use TAT after desensitization following positive skin tests53–55 due to the disadvantages of TIG such as its high price, rarity, complex preparation, and insufficient supply.

Analysis of Therapies for Sedation and Spasmolysis

Tetanus spasms are the most potent symptom, causing muscle tonicity, spasm, and autonomic instability.56 In severe cases, continuous spasms of the respiratory muscles lead to asphyxia and respiratory arrest,57,58 so controlling muscle spasms and sedation is one of the keys to treatment. However, excessive sedation and muscle relaxation may prolong the duration of tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation and increase the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia, tracheal stenosis, complicated deconditioning, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.59 In addition, the use of continuous drugs is associated with several adverse effects, which are usually caused by prolonged immobility and may result in muscle atrophy, eye injuries, nerve injuries due to compression, and deep vein thrombosis.60 Thus, moderate analgesic and muscle relaxation therapy is required. In this study, treatment regimens of analgesic, sedative, and muscle relaxation varied between different hospitals, with some using diazepam or midazolam alone, diazepam combined with a phenobarbital/hibernation mixture/midazolam in dual therapy, propofol combined with magnesium sulfate/midazolam, and even triple therapy for severe tetanus.12,61–63 These various treatment regimens may be related to the variable severity of the patient’s condition, individual differences in patient sensitivity to drugs, and the lack of relevant guidelines in China. According to the guidelines for managing accidental tetanus in adult patients, the drugs of choice to provide sedation, spasm control, and muscle relaxation in tetanus patients are benzodiazepines with opioids. For complete spasm control, a combination of diazepam and vecuronium is necessary.60 The combined application of Chinese and Western medicine may be a new direction with value to explore. In a previous report, the combined application of Chinese and Western medicine had a better effect on the control of tetanus convulsions and spasms than Western medicine alone. The inclusion of Chinese medicine could help reduce the dosage of Western medicine, prolong the interval of administration, shorten the course of treatment, and strengthen the effects of sedation, spasmodic relief, and calmness, thereby enabling Chinese and Western medicinal treatments to complement each other.64

Analysis of Tracheotomy and Outcomes

Due to persistent muscle spasms, tetanus, especially severe tetanus, is easily complicated by respiratory failure and airway management difficulties. Thus, early tracheal intubation or a tracheotomy to strengthen tracheal management is key to saving the patient.60 In this study, the leading causes of death were the abandonment of treatment by family members due to critical condition, asphyxia, and respiratory failure, in which asphyxia and respiratory failure accounted for 45.78%. Thus, the early implementation of a tracheotomy should be the top priority for critical tetanus patients. The result differs from a previous report showing that shock/multiple organ failure was the leading cause of death (72.9%).65 In this study, the mortality of tetanus in the normal group was 11.21%, and the tracheotomy rate reached 58.42%; the tracheotomy rate and mortality were similar to those in Japan25 but lower than those in a report from Brazil (44.5%).65 The tracheostomy rate was much greater than that in Ethiopia (10.5%), where the mean case fatality increased from 21% to 51% from 1996 to 2009.66 The low mortality in China may be related to the significant development of intensive care medicine technology and equipment, which could meet the intensive care needs of tetanus patients. Because fully configured ICUs and ventilator supportive care are not readily available in these developing countries, even when such resources are available, they may not be utilized when patients cannot afford their cost. Overall, the mortality rate associated with tetanus remains high.25

Perspectives

According to the results of this study, the keys to the prevention and treatment of tetanus in China are as follows. First, the prevention and control of non-neonatal tetanus remains challenging. The focus should be on preventing and reducing the incidence of adult tetanus. Second, the success rate of tetanus treatment in China, on the whole, is similar to that in developed countries. The focus of treatment should be on standardizing the use of sedative and spasmolytic drugs to reduce the adverse effects caused by excessive use.

Popular Science Work and Medical Training at the Grassroots Level

Since patients mainly come from the grassroots level, especially rural areas, the causative agent of tetanus, Clostridium tetani, is widespread in the environment and cannot be eradicated.67 To reduce the incidence of tetanus in China, the focus of work must be on grassroots solutions such as popularizing tetanus prevention and treatment knowledge among the people, strengthening their awareness of tetanus prevention, and promoting daily labor protection. Additionally, those with injuries should quickly go to the hospital for standardized debridement and disinfection and especially avoid treating wounds using at-home methods, which can increase the risk of tetanus infection. These measures could help prevent minor damage from becoming severe disease. As tetanus patients generally have light and minor injuries, they often do not go to tertiary hospitals. Thus, grass-roots hospitals are the first choice for tetanus prevention and treatment. The understanding of tetanus among grass-roots physicians and their ability to handle wounds, to a large extent, determine whether a patient will suffer from tetanus or receive an early diagnosis. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen training in grass-roots hospitals, in order to improve their understanding of tetanus, correctly understand passive immunity and active immunity, and standardize wound management, which are essential to prevent tetanus.59

Rational Formulation of an Immunization Schedule for Adults

The actual global burden of disease is unknown, as reliable figures are only collected for cases of neonatal tetanus. In 2015, the disease caused an estimated 48,199 to 80,042 deaths.68 However, these deaths could have been prevented by an already available, inexpensive, and effective vaccine.69 One of the leading reasons for such deaths is that the level of tetanus antibodies and protection rate of people over 40 years is extremely low in China. This factor is similar in developed countries, where trends from countries with well-established immunization programs show increasing tetanus cases among the elderly related to seroepidemiologic data showing declining immunity with advanced age.3 Therefore, China must improve its national monitoring and reporting system, analyze antibodies against tetanus, formulate a rational immunization plan, and vaccinate people with low antibody levels. Since effective antibody concentrations only remain ten years after vaccination in most people,70 it is necessary to vaccinate once every ten years.

Standardizing the Use of Sedative and Spasmolytic Drugs

Given the side effects of long-term and excessive drug use, standardized treatment is essential to improve prognosis. The guidelines for the management of accidental tetanus in adult patients can be referred to for relevant information. Unfortunately, these guidelines do not clarify how to choose drugs for patients with different grades of tetanus. Chinese people have used traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years, so combining Chinese and Western medicine may represent a new direction with value to explore.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the overall success rate of tetanus treatment in China has dramatically improved. However, the prevention and control of non-neonatal tetanus are still inadequate, and the focus should be placed on the prevention of adult tetanus and standardizing the use of sedatives and spasmolytic drugs. Additionally, tetanus prevention and treatment knowledge should be popularized among the people, and training in grass-roots hospitals should be improved. The combined application of Chinese and Western medicine may also be a new direction for reducing the dosage of sedative and spasmolytic drugs.

Abbreviations

TAT, tetanus antitoxin; TIG, tetanus immunoglobulin; T, tracheotomy.

Data Sharing Statement

The full de-identified database will be made available for independent analysis on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This work was supported by Key Research and Development Program of Ningxia (2022BEG02049).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. Yen LM, Thwaites CL. Tetanus [published correction appears in Lancet. 2019 Apr 27;393(10182):1698]. Lancet. 2019;393(10181):1657–1668. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33131-3

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tetanus surveillance --- United States, 2001–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(12):365–369.

3. Quinn HE, McIntyre PB. Tetanus in the elderly--An important preventable disease in Australia. Vaccine. 2007;25(7):1304–1309. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.084

4. Gui-jun N, Dan W, Jun-hong L, et al. Global immunization schedules, vaccination coverage rates and incidences of diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis, 2010–2014. Cnin J Vaccines Immun. 2016;22(02):159164. doi:10.19914/j.cjvi.2016.02.007

5. Tosun S, Batirel A, Oluk AI, et al. Tetanus in adults: results of the multicenter ID-IRI study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36(8):1455–1462. doi:10.1007/s10096-017-2954-3

6. Mahieu R, Reydel T, Maamar A, et al. Admission of tetanus patients to the ICU: a retrospective multicentre study. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(1):112. doi:10.1186/s13613-017-0333-y

7. Ogundare EO, Ajite AB, Adeniyi AT, et al. A ten-year review of neonatal tetanus cases managed at a tertiary health facility in a resource poor setting: the trend, management challenges and outcome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(12):e0010010. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0010010

8. GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2

9. Narang M, Khurana A, Gomber S, Choudhary N. Epidemiological trends of tetanus from East Delhi, India: a hospital-based study. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7(2):121–124. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2013.07.006

10. Fan Z, Zhao Y, Wang S, Zhang F, Zhuang C. Clinical features and outcomes of tetanus: a retrospective study. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:1289–1293. doi:10.2147/IDR.S204650

11. Morita T, Tsubokura M, Tanimoto T, Nemoto T, Kanazawa Y. A need for tetanus vaccination before restoration activities in Fukushima, Japan. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2014;8(6):467–468. doi:10.1017/dmp.2014.109

12. Hailing L, Huan C, HaiJun L. Clinical observation of 38 cases of traumatic tetanus treated with continuous intravenous diazepam by micro-pump. J Guangdongmed Coll. 2012;30(01):45–46.

13. Xiaobiao C. Observation of pharmaceutical care in the treatment of tetanus patients. China J Pharma Econ. 2018;13(05):57–59.

14. Lan Z. Analysis of clinical treatment of 90 tetanus patients. Asia Pacific Trad Med. 2012;8(04):63–64.

15. Thwaites CL, Beeching NJ, Newton CR. Maternal and neonatal tetanus. Lancet. 2015;385(9965):362–370. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60236-1

16. Anuradha S. Tetanus in adults--a continuing problem: an analysis of 217 patients over 3 years from Delhi, India, with special emphasis on predictors of mortality. Med J Malaysia. 2006;61(1):7–14.

17. Olum S, Eyul J, Lukwiya DO, Scolding N. Tetanus in a rural low-income intensive care unit setting. Brain Commun. 2021;3(1):fcab013. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcab013

18. Surabhi GS, Prithviraj R, Lavanya R. Is adult tetanus an endemic in India? Natl J Commun Med. 2022;13:435–438. doi:10.55489/njcm.13072022468

19. Gunawan APK, Ganiem AR, Aminah S, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with tetanus at Dr. Hasan Sadikin General Hospital Bandung 2015–2019. Althea Med J. 2022;9. doi:10.15850/amj.v9n3.2299

20. Andersen A, Bjerregaard-Andersen M, Rodrigues A, Umbasse P, Fisker AB. Sex-differential effects of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine for the outcome of paediatric admissions? A hospital based observational study from Guinea-Bissau. Vaccine. 2017;35(50):7018–7025. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.047

21. Rani K, Kalyani D, Shankar K. Assessment of incidence and mortality of tetanus at Sir Ronald Ross Institute of Tropical and Communicable Diseases (Govt. Fever Hospital), Hyderabad – five year study. J Dent Med Sci. 2016;36–40. doi:10.9790/0853-1504053640

22. Feroz A, Rahman MH. A ten-year retrospective study of tetanus at a teaching hospital in Bangladesh. J Bangladesh Coll Phys Surg. 2007;25(2). doi:10.3329/jbcps.v25i2.371

23. Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Dass RM, Mbelenge N, Mshana SE, Gilyoma JM. Ten-year experiences with Tetanus at a Tertiary hospital in Northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 102 cases. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:20. doi:10.1186/1749-7922-6-20

24. Qing S, Guang-Liang H, Guangju Z. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics changes of 47cases of tetanus. J Clin Emerg. 2015;16(09):705–708. doi:10.13201/j.issn.1009-5918.2015.09.013

25. Nakajima M, Aso S, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Clinical features and outcomes of tetanus: analysis using a National Inpatient Database in Japan. J Crit Care. 2018;44:388–391. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.12.025

26. Fawibe AE. The pattern and outcome of adult tetanus at a sub-urban tertiary hospital in Nigeria. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20(1):68–70.

27. Amare A, Melkamu Y, Mekonnen D. Tetanus in adults: clinical presentation, treatment and predictors of mortality in a tertiary hospital in Ethiopia. J Neurol Sci. 2012;317(1–2):62–65. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2012.02.028

28. Qiang C, Yuhua Q, Yun W, et al. Tetanus IgG antibody levels among healthy people in Jiangsu province, 2018. Chin J Vaccines Immun. 2020;26(01):38–41. doi:10.19914/j.cjvi.2020.01.008

29. Meizhen L, Xiaofang P, Lingfeng Z, et al. IgG antibody level against tetanus among medical-visiting population in Guangdong province in 2018. Chin J Vaccines Immun. 2020;26(05):525–528. doi:10.19914/j.cjvi.2020.05.009

30. Shan Y, Jianming L, Peng T, et al. Serological surveillance of diphtheria and tetanus antibody levels among healthy population in Luoyang city, Henan province, during 2019–2020. Henan J Prev Med. 2022;33(04):294–296. doi:10.13515/j.cnki.hnjpm.1006-8414.2022.04.015

31. Xiuling F, Yan W, Bingqiang D. Experience in treatment of 50 cases of severe tetanus. China Pract Med. 2012;7(18):91–92. doi:10.14163/j.cnki.11-5547/r.2012.18.086

32. Jiangli P, Yonggang C, Lu W, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic risk factors of tetanus patients in a hospital from 2013 to 2020. J Kunming Med Univ. 2021;42(11):87–92.

33. Linlin X. Analysis of treatment strategies and prognostic factors of 291 adult tetanus patients. Changchun Univ Chin Med. 2021. doi:10.26980/d.cnki.gcczc.2021.000423

34. Wei T. Effect of comprehensive treatment on severe tetanus in adults. Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;5(14):92–93. doi:10.16282/j.cnki.cn11-9336/r.2017.14.072

35. Xusen H, Jianchu W, Haizhou T, et al. Treatment experience of 45 cases of adult severe tetanus. Shaanxi Med J. 2008;15(04):510–511.

36. Zhen L. To explore the influence of nursing intervention on adult patients with tetanus. China Continuing Med Educ. 2015;7(13):206–207.

37. Jianjun X. Analysis of the misunderstanding of prevention and treatment of tetanus. Asia Pacific Trad Med. 2013;9(07):127–128.

38. Marulappa VG, Manjunath R, Mahesh Babu N, et al. A ten year retrospective study on adult tetanus at the Epidemic Disease (ED) Hospital, Mysore in Southern India: a review of 512 cases. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6(8):1377–1380. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2012/4137.2363

39. Chuan H, Liming M, Being-zhi T, et al. Curative effect observation of combining traditional Chinese and western medicine treatment of 25 cases of tetanus. J Inner Mongolia Med. 2013;32(32):22. doi:10.16040/j.carolcarrollnkicn15-1101.2013.32.071

40. Xiang K, Wang Q-L, Peng C-X, et al. Severe tetanus patients used artificial nasal airway management effect of. J Nurs. 2010;(4):70–71. doi:10.16460/j.issn1008-9969.2010.04.030

41. BC Wen. Efficacy analysis of cisatracurium besylate combined with midazolam in the treatment of severe tetanus under mechanical ventilation. Chin Pract Med. 2013;8(5):177–178. doi:10.14163/j.carolcarrollnki.11-5547/r.2013.05.144

42. Xiangyang L. 40 cases of adult tetanus clinical analysis. Guide China Med. 2013;11(17):641–642. doi:10.15912/j.carolcarrollnkigocm.2013.17.266

43. Adekanle O, Ayodeji O, Olatunde L. Tetanus in a rural setting of South-Western Nigeria: a ten-year retrospective study. Libyan J Med. 2009;4(2):78–80. doi:10.4176/081125

44. Hongting Z, Xiuping W, Yuqing C, et al. The application of comfortable nursing in patients with severe tetanus nursing experience. Guide China Med. 2015;13(14):240–241. doi:10.15912/j.carolcarrollnkigocm.2015.14.183

45. Nannan X. Clinical Characteristics of Adult Tetanus and Detection of Tetanus Antibody Level in Shandong Province. Shandong University; 2018.

46. Fuzhuo L. Nursing and observation of 94 patients with tetanus. Front Med. 2013;74(7):239–240.

47. China Trauma Care Alliance, Trauma Medical Center, Peking University. Chinese expert consensus on tetanus immunoprophylaxis. Chin J Surg. 2018;56(03):161–167. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2018.03.001

48. Xiaomeng Z, Yanhua W, Chuanlin W. Development history and application of passive immune preparation for tetanus. Chin J Microbiol Immunol. 2018;38(06):472–475.

49. Shengjun Y, Junsheng L, Xiangyun G, et al. Clinical APPLICATION OF human tetanus IMMUNOGLOBULIN AND equine SERUM tetanus ANTItoxin. Chin J Emerg Med. 2004;2004(05):350–351.

50. Qing H, Luhong C. Clinical application of human tetanus immunoglobulin, tetanus antitoxin and tetanus toxoid. Chin J Emerg Med. 2003;1(08):559–560.

51. Jifeng W, Pu H, Wenzong L, et al. Tetanus in adults: a combined treatment analysis of 229 cases. China Anim Damage Treat Proc Peak. 2019;71–74. doi:10.26914/Arthurc.nkihy.2019.014961

52. Su WD, Tan H, Huang H. Analysis of clinical characteristics of 36 cases of adult tetanus. Clin Med Res Pract. 2018;3(11):43–44. doi:10.19347/j.carolcarrollnki.2096-1413.201811020

53. Li H, Ye L. Emergency nursing of 57 cases of adult tetanus. West China Med J. 2011;26(11):1713–1714.

54. Huaxing Y, Qinghe L. Treatment of 45 cases of adult tetanus. Contemp Med. 2011;17(33):40–41.

55. Jinfeng D, Yufeng T, Yun Z. Analysis of diagnosis and treatment of adult refractory tetanus. J Pract Hosp Clinic. 2013;10(02):98–99.

56. Schiavo G, Matteoli M, Montecucco C. Neurotoxins affecting neuroexocytosis. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(2):717–766. doi:10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.717

57. LZ Pan. Nursing of severe tetanus patients with tracheotomy. Med Inform. 2011;24(01):207–208.

58. Xu B, Ge K, Zhuang Y-G, et al. Treatment of severe tetanus infection. J Tongji Univ. 2010;31(05):56–58+62.

59. Rodrigo C, Fernando D, Rajapakse S. Pharmacological management of tetanus: an evidence-based review. Crit Care. 2014;18(2):217. doi:10.1186/cc13797

60. Lisboa T, Ho YL, Henriques filho GT, et al. Guidelines for the management of accidental tetanus in adult patients. Diretrizes para o manejo do tétano acidental em pacientes adultos. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2011;23(4):394–409. doi:10.1590/S0103-507X2011000400004

61. Liqin F, Lifen C, Guiying H, et al. Application of prone position ventilation in patients with severe tetanus complicated with atelectasis. Hebei Med J. 2017;39(17):2665–2666+2669. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-7386.2017.17.030

62. Wei C, Yong-xiang Z, Biao J, et al. Clinical analysis of 24 cases of tetanus. Maternal Infant World. 2016;2016(2):37.

63. Wei-min M, Shao-yang W, Hai-zhou L, et al. Heavy tetanus in adults 20 cases of clinical analysis. Guide China Med. 2015;13(27):90–91. doi:10.15912/j.carolcarrollnkigocm.2015.27.068

64. Jianxun H, Shoucheng D. Treatment of tetanus with integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine in 97 cases. Chin J Integr Trad West Med Surg. 2012;18(01):79–80. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-6948.2012.01.028

65. Nóbrega MV, Reis RC, Aguiar IC, et al. Patients with severe accidental tetanus admitted to an intensive care unit in Northeastern Brazil: clinical-epidemiological profile and risk factors for mortality. Braz J Infect Dis. 2016;20(5):457–461. doi:10.1016/j.bjid.2016.06.007

66. Amare A, Yami A. Case-fatality of adult tetanus at Jimma University Teaching Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11(1):36–40.

67. Thwaites CL, Loan HT. Eradication of tetanus. Br Med Bull. 2015;116(1):69–77. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldv044

68. Loan HT, Yen LM, Kestelyn E, et al. Intrathecal Immunoglobulin for treatment of adult patients with tetanus: a randomized controlled 2x2 factorial trial. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:58. doi:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14587.2

69. Kyu HH, Mumford JE, Stanaway JD, et al. Mortality from tetanus between 1990 and 2015: findings from the global burden of disease study 2015. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):179. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4111-4

70. Zhen-yu G, Xun-liang G. World Health Organization position paper on tetanus vaccine. Dis Surveill. 2017;32(5):441–444. doi:10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2017.05.022

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.