Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Work Stress and Personal and Relational Well-Being Among Chinese College Teachers: The Indirect Roles of Sense of Control and Work-Related Rumination

Received 20 April 2023

Accepted for publication 13 July 2023

Published 24 July 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2819—2828

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S418077

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Qinglu Wu,1 Nan Zhou2

1Institute of Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Zhuhai, People’s Republic of China; 2Faculty of Education, University of Macau, Macau, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Nan Zhou, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The association between work stress and well-being has been well documented. However, the underlying mechanism for such association is not clear, especially in terms of how work stress relates to both personal and relational well-being. Based on the Conservation of Resources Theory and the Stress Process Model, the present study examined the potential indirect roles of the sense of control and the work-related rumination in the associations between work stress and both personal and relational well-being.

Methods: Data were collected from 536 married Chinese university teachers (Mage = 39.40 + 7.64, 38.6% males) through an online survey. Analyses were conducted using structural equation modeling via Mplus.

Results: Work stress was indirectly associated with life satisfaction through (a) sense of control, (b) work-related rumination, and (c) a sequential pathway from sense of control to work-related rumination. Work stress was indirectly associated with relationship satisfaction through sense of control.

Conclusion: Findings suggest that sense of control would be an important linking mechanism underlying the association between work stress and college teachers’ well-being. Personal well-being may be more vulnerable to work-related rumination than relational well-being. Insights for prevention and intervention efforts in enriching college teachers’ well-being are discussed.

Keywords: work stress, sense of control, work-related rumination, well-being, college teachers

Introduction

Work stress has been consistently associated with individuals’ psychosocial maladjustment (eg, compromised mental health, sleep quality, self-efficacy, and organizational commitment).1–3 Work stress not only may compromise personal functioning but also impairs relational functioning.4 Personal well-being (eg, life satisfaction) and relational well-being (eg, relationship satisfaction) are two important aspects of psychosocial adjustment that are vulnerable to work stress.5–8 Individuals with high levels of work stress usually experience more emotional exhaustion and work-family conflict and become less satisfied with both their lives and marriages.1,6,8,9 Indirect roles of psychological capital and self-esteem have been found in the associations between work stress and personal and relational well-being.7,10 Even though a small body of studies have identified underlying mechanisms in associations between work stress and well-being, scant studies have investigated the underlying mechanisms in the associations between work stress and the two types of well-being simultaneously. Given that personal and relational well-being are distinct but related and the linking mechanisms underlying the associations between work stress and personal and relational well-being may overlap, without considering both personal and relational well-being simultaneously, the examinations may not provide a complete picture of the unique pathways among these associations. To address this gap, the present study examined the potential indirect roles of sense of control and work-related rumination in the associations between work stress and both personal and relational well-being among college teachers, who usually face multiple faculty stressors in the university setting such as organizational inadequacy, financial inadequacy, teaching-research conflict, and unfavourable student quality.2

The Potential Indirect Role of the Sense of Control

The Conservation of Resources Theory (CRT) has been widely employed to investigate the implications of resource losses (eg, sense of community, social support) that result from various stress (eg, COVID-19 stress, traumatic stress) for individual developmental outcomes.11–14 The CRT highlights the importance of personal resources for individuals’ well-being and emphasizes that resource loss (eg, compromised personal control, impaired optimism) is the principal element in the stress process.15,16 Specifically, people are motivated to preserve personal resources, which could be undermined under high stress (resource loss) and further lead to impaired well-being. Individuals’ sense of control is among the critical personal resources that may serve as a linking mechanism that help explain how work stress relates to college teachers’ well-being.

Sense of control is an adaptive value that provides the motivation to make efforts to change personal plight.17 Sense of control has been associated with enhanced personal well-being (eg, life satisfaction) and adaptive behaviors (eg, physical activity), and decreased mental health problems (eg, depressive symptoms).18–20 Moreover, positive associations have been found between personal control and relationship outcomes (eg, relationship satisfaction, commitment, and closeness) among couples.21,22 Individuals with high levels of self-control are more likely to regulate themselves (eg, emotions, thoughts, and behavioral impulses) and present pro-relationship behaviors (eg, forgiveness), which in turn could promote relationship functioning.21

Association between work stress and sense of control also has been identified in previous research. For instance, work stress has been related to anxiety through sense of control among medical workers in the COVID-19 situation.23 Moreover, a three-wave longitudinal study has revealed that high level of work stress compromised self-control and further led to emotional problems (eg, depressive and anxious symptoms) among kindergarten teachers.24 Overall, based on the theoretical and empirical evidence, work stress may be indirectly related to both personal and relational well-being through sense of control.

The Potential Indirect Role of Work-Related Rumination

The Stress Process Model (SPM) provides theoretical support for the indirect role of work-related rumination in the association between work stress and well-being. The SPM emphasizes that an initial stressor can lead to negative consequences by facilitating secondary stressors (also called stress proliferation).25,26 Secondary stressors could be adverse experiences (eg, discrimination, caregiving burden) or damaged resources (eg, compromised self-mastery, self-esteem).27–30 Work stress, as a critical form of primary stressors, would foster individuals’ negative experiences of work-related rumination (secondary stressor), which may relate to personal and relational well-being as a result.

Rumination is a responding mode to distress that includes repetitively and passively focusing on its symptoms and possible causes and impacts.31 Rumination is characterized by its perseverative thinking and treated as a maladaptive coping to stressful experiences.32 Work-related rumination is a cognitive process of continuously thinking about work (eg, work-related tasks and activities) during non-work time.33,34 Work-related rumination is the consequence of work stress, which has been supported across studies employing different populations (eg, employees, university teachers).35–37 Employees with mountains of unfinished work tasks are dissatisfied with their own competence and may be more likely to repetitively think about their work at their leisure time (eg, weekend).35 This also applies to college teachers who typically are facing high levels of work stress and thus tend to ruminate over their work issues.36

Given that cognitive overload in non-work hours impairs the off-job recovery and well-being (eg, vigor, fatigue, negative mood), the negative effect of work-related rumination, as a cognitive process that may result in cognitive overload, has been highlighted in the field of recovery research.38–40 Work-related rumination has been associated with both personal and relational well-being.39,41,42 A daily diary study revealed that psychotherapeutic practitioners’ daily work-related rumination is associated with bad mood, increased nervousness, and tiredness after work.40 Similarly, elementary and secondary school teachers with high work-related rumination are more likely to have worse sleep quality and experience more negative mood.43,44 Moreover, workplace incivility is associated with work-family conflict through rumination related to work among university faculty members.42 Based on the SPM and empirical evidence, work-related rumination may serve as the linking mechanism through which work stress relates to personal and relational well-being.

The Relationship Between Sense of Control and Work-Related Rumination

The relationship between personal control and rumination has been identified in various populations (eg, patients suffering psychiatric disorders, community sample).45,46 Some studies revealed that rumination served as a linking mechanism in the associations of personal control with mental health outcomes (eg, PTSD symptoms and depressive symptoms) and aggressive behaviors.46–49 These studies emphasize that personal control is a substantial resource and individuals with heightened levels of sense of control (either the general control or a specific attention control) are less likely to ruminate, which may further contribute to reduced mental health problems and interpersonal mistreatment. In addition, some studies that examine the underlying mechanisms in the stress–outcome relationships have discovered that compromised personal resources (eg, diminished self-compassion and academic engagement) resulting from stress usually come before negative experiences (eg, shame, low academic achievement).50,51 College teachers’ drained sense of control due to multiple stressors at work (eg, teaching, research) may result in insufficient personal resources to protect them from work-related rumination.2 Thus, work stress may be indirectly related to both personal and relational well-being through a sequential pathway from sense of control to work-related rumination among college teachers.

The Present Study

Although the association between work stress and well-being has been well established, the mechanisms underlying this association are not clear yet, in particular, when simultaneously considering the implications of work stress for both personal and relational well-being. Based on the CRT and the SPM, the present study investigated the potential indirect roles of sense of control and work-related rumination in the associations between work stress and life satisfaction and relationship satisfaction among college teachers. We hypothesized that work stress would be associated with both life and relationship satisfaction through (a) sense of control, (b) work-related rumination, and (c) a sequential pathway from sense of control to work-related rumination.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Data of the present study were from a project on the relationship between work stress and psychosocial adjustment among Chinese college teachers. Convenience sampling was used, and recruitment information was spread by college teachers in their social networks. Participants were informed the research purpose, confidentiality, and the principle of voluntary participation. They provided informed consent before filling out the online survey. Qualified participants received a monetary reward (80 RMB, approximately US $ 11). The project was approved by the research ethics committee of the School of Social Development and Public Policy at Beijing Normal University before data collection.

Overall, 800 participants registered and completed the online survey. After excluding cases who failed the attention check (n = 72), whose affiliation is outside China (n = 1), and who were not currently married (n = 191), the rest of the sample was retained (n = 536; 207 males). The sample consisted of 191 (35.6%) teachers from national key institutions (The 211/985 National Key Universities), 305 teachers (56.9%) from provincial key institutions, and 33 teachers (6.2%) from vocational and technical institutions. For the region of universities, 135 (25.2%) teachers were from southern China, 96 (17.9%) from eastern China, 47 (8.8%) from northern and northeastern China, and 253 (47.2%) from western and central China. The average age of the participants was 39.40 (SD = 7.64) years old. The average duration of marriage of the participants was 11.85 years (SD = 9.26). Nearly, all of the participants (99.8%) obtained the bachelor degree or above. Among them, 344 (64.3%) had a PhD degree. In terms of teaching experiences, 29.5% of participants had less than 5 years of teaching experience, 25.5% had 5–10 years, 30.6% had 11–20 years, and 14.4% had more than 20 years. Regarding professional ranks, 7.8% were categorized as senior research assistants, 44.4% lectures/assistant professors, 34.3% associate professors, and 13.4% professors.

Measures

Work Stress

Work stress was assessed by the 22-item Revised Sources of Faculty Stress scale (R-SFS),2 which assesses the stressors relevant to higher education including recognition inadequacy, perceived organizational inadequacy, factors intrinsic to teaching, financial inadequacy, teaching-research conflict, unfavorable student quality, and new challenges. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results showed that the measurement model for faculty stress fit the data well (χ2 = 38.78, df = 11, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.034, RMSEA = 0.069 with 90% CI [0.046, 0.093]). Example items include “Teaching schedules are too tight” and “Too much research work after teaching hours.” The items were rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher mean scores indicated higher levels of work stress. Cronbach’s α for the whole scale was 0.92 and ranged from 0.72 to 0.91 for subscales.

Sense of Control

Sense of control was assessed by the personal mastery scale.17 This scale includes 4 items measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Example items are “Whether or not I am able to get what I want is in my own hands”, and “I can do just about anything I really set my mind to.” Higher mean scores indicated higher levels of sense of control. Cronbach’s α in the present study was 0.87.

Work-Related Rumination

University teachers’ repetitive thoughts related to work during non-work hours were measured by the affective rumination subscale of the work-related rumination scale.52 The 5 items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). A higher value represented a higher level of work-related rumination. Example items are “Are you irritated by work issues when not at work?” and “Do you become fatigued by thinking about work-related issues during your free time?” Cronbach’s α in the present study was 0.92.

Personal Well-Being

Personal well-being was indicated by life satisfaction, which was assessed by the 5-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS).53 Participants rated their responses on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Example items are “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”, and “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life.” Cronbach’s α in the present study was 0.89.

Relational Well-Being

Relational well-being was indicated by relationship satisfaction, which was measured by the Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS).54 The 7 items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). Example items are “In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship?” and “How good is your relationship compared to most?” Higher mean scores indicated higher levels of satisfaction toward marriage. Cronbach’s α in the present study was 0.93.

Covariates

Covariates in the present study included demographic variables (ie, age, sex, educational level), variables related to professionals (ie, years of teaching, professional title, concurrent administrative position) and participants’ residential regions (ie, north and northeastern China, eastern China, southern China, and western and central China) and college levels/ranking (ie, national key institutions, provincial key institutions, junior vocational and technical institutions).

Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling was used to examine the hypothesized model with Mplus (version 8.3). Missing data were addressed using the full information maximum likelihood method. Robust maximum likelihood estimator that allows for non-normal distribution data was employed for structural equation modeling.55 The model fit indices employed to evaluate the model fit were χ2, RMSEA (<0.08), CFI (>0.90), and SRMR (<0.08).56 A resampling approach with bias-corrected bootstrapping (5000 times) was used to address the sampling distribution of the indirect effects. The significance of the indirect effects was assessed by bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A CI that does not include zero indicates that the corresponding indirect effect was significant.57 Faculty stress was specified as a latent variable and indicated by 7 dimensions; other key study variables were specified as manifest variables. The covariates (ie, age, sex, educational level, years of teaching, professional title, concurrent administrative position, and regions and levels of universities) were included in the model.

Results

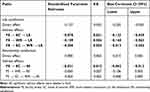

The descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of key variables are showed in Table 1. Associations among key variables were in the expected directions.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among the Key Variables |

The model fit of hypothesized model was adequate (Figure 1; χ2 (127) = 309.971, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.907, SRMR = 0.041, RMSEA = 0.052 with 90% CI [0.045, 0.059]). Faculty stress was negatively associated with life satisfaction (β = −0.127, SE = 0.053, p = 0.016) but was not associated with relationship satisfaction (β = −0.085, SE = 0.062, p = 0.169). All the indirect effects involving the association between faculty stress and life satisfaction were significant (Table 2). Specifically, faculty stress was associated with life satisfaction through sense of control (b = −0.126, SE = 0.034, 95% CI [−.203, −0.065], β = −0.078), work-related rumination (b = −0.174, SE = 0.042, 95% CI [−.265, −0.098], β = −0.109), and a serial pathway from sense of control to work-related rumination (b = −0.009, SE = 0.004, 95% CI [−.021, −0.004], β = −0.006). Faculty stress was only indirectly associated with relationship satisfaction via sense of control (b = −0.031, SE = 0.012, 95% CI [−.061, −0.012], β = −0.031).

|

Table 2 Direct and Indirect Effects of Faculty Stress on Life and Relationship Satisfaction |

|

Figure 1 Paths and standardized path coefficients for hypothesized model. Notes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. |

Discussion

Although the implications of work stress for individuals’ well-being have been well documented, the underlying mechanisms for how work stress compromises personal and relationship well-being are still not clear yet. The present study sought to address this gap by examining the indirect roles of sense of control and work-related rumination in the associations between work stress and both personal and relational well-being among college teachers. Results revealed that sense of control and work-related rumination served as critical linking mechanisms that accounted for the relationships between work stress and college teachers’ personal and relational well-being. The findings fit well within the CRT, which highlights the importance of personal resources for maintaining and promoting individuals’ well-being. Moreover, our findings also support the SPM that emphasizes the stress proliferation in the stress–outcome process. Initial daily work stress would lead to two secondary stressors in the forms of compromised personal resources (ie, sense of control) and negative experiences (ie, work-related rumination), which further impair well-being.

First, work stress was associated with both personal and relational well-being through sense of control among college teachers. This finding indicates that sense of control is important for work stress to transmit its negative effect into well-being. Individuals who perceive high personal control and mastery are more likely to be satisfied with their lives and relationships.20,22 However, sense of control is vulnerable to the work stress.23 College teachers facing high workload may experience heightened levels of emotional problems and ego depletion,24,58 which make them difficult to manage their emotions and impulsive behaviors in life and effectively deal with conflict with partners, resulting in diminished personal and relational well-being as a result.

Second, work stress was associated with personal well-being through rumination and a sequential pathway from sense of control to work-related rumination. This finding supports the tenet of the SPM,25,26 which emphasizes that initial stressors transmit negative effect into adverse consequences through facilitating secondary stressors, including the negative experiences and the impaired personal resources.27,29 In addition, this finding also echoes the findings of the studies that individuals with high self-control are less likely to fall into rumination.47,48 College teachers enduring high work stress may lose sense of control that they strive to maintain, which further would compromise their capacities to disengage or shift attention away from repetitive thoughts related to work responsibilities. This negative experience, in turn, could drain their energy and inhibit the recovery in non-work hours, resulting in the diminished personal well-being.

Note that the present study found that work stress was not associated with relational well-being through the pathways involving work-related rumination. One potential reason for this null finding is that work-related rumination may be a distal factor for marital satisfaction. In support of this idea, based on 43 dyadic longitudinal studies, a recent large-scale meta-analysis found that relationship satisfaction is more explained by relationship-specific variables (eg, commitment, conflict) than individual difference variables (eg, negative affect, depression).59 Thus, repetitive thoughts on work may indirectly relate to relational well-being through triggering relationship-specific factors such as work-family conflict,60 which can be a promising direction for future studies.

Implications

The present study has some theoretical and practical implications. This study simultaneously investigated the underlying mechanisms in the associations between work stress and both personal and relational well-being, which provides the specificity as how work stress dampens individuals’ well-being across multiple life domains. The identification of the indirect role of sense of control in the associations between work stress and both personal and relational well-being suggests that depleted personal resource is substantial for transmitting the negative effect of work stress into well-being.61 Moreover, the finding that indirect role of work-related rumination in the association between work stress and personal rather than relational well-being indicates that personal well-being may be more vulnerable to work-related rumination than relational well-being. This finding further documents the importance of differentiating personal versus relational well-being when investigating the mechanism in the association between work stress and individuals’ well-being. In addition, differences of these two types of well-being should be considered when developing intervention to enrich the well-being of individuals who suffer from high work stress. A recent scoping review suggests that the mindfulness-based intervention is helpful for reducing teachers’ work stress and emotional exhaustion.62 Treatments and approach that focus on reducing work stress and improving personal control may be useful in enhancing both personal and relational well-being.62,63 Interventions and skills (eg, boundary management, engagement in recovery activities) focusing on reducing work-related rumination or enhancing psychological detachment from work may be helpful for improving personal well-being among those haunted by work stressors.64

Limitations

Some limitations of the present study need to be noted. First, given that the present study employed a cross-sectional design, the causal relationships among key variables cannot be inferred. Even though the documented associations were theoretically based, the directions of these associations may be the reverse65, which could be tested using cross-lagged models in the future longitudinal research. Second, the present study relied on the self-report data, which may increase the risks of social desirability and self-report bias. Future studies could employ both self reports and physiological measures of work stress (eg, hair cortisol concentrations) to reduce the common method bias.66 Third, even though the present study assessed and controlled for a series of critical socio-demographic variables in the analyses, some other relevant work characteristics (eg, major and departments of teachers, work time) were not assessed in the study,36 which can be assessed and included to replicate the current findings in future studies.

Conclusion

The present study identified the specific indirect pathways in the associations between work stress and personal and relational well-being among college teachers. Work stress was associated with personal well-being through a) sense of control, b) rumination and (c) a sequential pathway from sense of control to work-related rumination. Work stress was associated with relational well-being through sense of control rather than the pathways involving work-related rumination. Findings support the tenets of the CRT and the SPM that the impairment of personal resources and stress proliferation are important for understanding how work stress relates to individuals’ well-being across multiple life domains. Moreover, differentiating personal and relational well-being should be considered when investigating the underlying mechanisms in the association between work stress and individuals’ well-being.

Ethical Statement

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the research ethics committee of the School of Social Development and Public Policy at Beijing Normal University (SSDPP-HSC2022006) before data collection. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Foundation for Young Talents in Higher Education of Guangdong Province [2021WQNCX307], and Start-Up Fund of Beijing Normal University at Zhuhai [310432101].

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Brady LL, McDaniel SC, Choi Y-J. Teacher stress and burnout: the role of psychological work resources and implications for practitioners. Psychol Sch. 2022. doi:10.1002/pits.22805

2. Yin H, Han J, Perron BE. Why are Chinese university teachers (not) confident in their competence to teach? The relationships between faculty-perceived stress and self-efficacy. Int J Educ Res. 2020;100:101529. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101529

3. Gluschkoff K, Elovainio M, Kinnunen U, et al. Work stress, poor recovery and burnout in teachers. Occup Med (Chic Ill). 2016;66(7):564–570. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqw086

4. Xu F, Hilpert P, Nussbeck FW, Bodenmann G. Testing stress and dyadic coping processes in Chinese couples. Int J Stress Manag. 2018;25(1):84–95. doi:10.1037/str0000051

5. Cho I-K, Lee J, Kim K, et al. Schoolteachers’ resilience does but self-efficacy does not mediate the influence of stress and anxiety due to the COVID-19 pandemic on depression and subjective well-being. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.756195

6. Hamama L, Ronen T, Shachar K, Rosenbaum M. Links between stress, positive and negative affect, and life satisfaction among teachers in special education schools. J Happiness Stud. 2013;14:731–751. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9352-4

7. Debrot A, Siegler S, Klumb PL, Schoebi D. Daily work stress and relationship satisfaction: detachment affects romantic couples’ interactions quality. J Happiness Stud. 2018;19(8):2283–2301. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9922-6

8. Carnes AM. Bringing work stress home: the impact of role conflict and role overload on spousal marital satisfaction. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2017;90(2):153–176. doi:10.1111/joop.12163

9. Sharma V, Chalotra AK, Bhat DAR. Job stress and work-family conflict: moderating role of mentoring in call center industry. Int J Early Childhood Special Educ. 2022;14(2):115–122. doi:10.9756/INT-JECSE/V14S2.15

10. Wang Z, Liu H, Yu H, Wu Y, Chang S, Wang L. Associations between occupational stress, burnout and well-being among manufacturing workers: mediating roles of psychological capital and self-esteem. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):364. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1533-6

11. Lambert JE, Witting AB, James S, Ponnamperuma L, Wickrama T. Toward understanding posttraumatic stress and depression among trauma-affected widows in Sri Lanka. Psychological Trauma Theory Res Practice Policy. 2019;11(5):551–558. doi:10.1037/tra0000361

12. Haj-Yahia MM, Sokar S, Hassan-Abbas N, Malka M. The relationship between exposure to family violence in childhood and post-traumatic stress symptoms in young adulthood: the mediating role of social support. Child Abuse Neglect. 2019;92:126–138. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.023

13. She R, Wong KM, Lin JX, Leung KL, Zhang YM, Yang X. How COVID-19 stress related to schooling and online learning affects adolescent depression and Internet gaming disorder: testing Conservation of Resources theory with sex difference. J Behav Addictions. 2021;10(4):953–966. doi:10.1556/2006.2021.00069

14. Yu T, Li JY, He LD, Pan XF. How work stress impacts emotional outcomes of Chinese college teachers: the moderated mediating effect of stress mindset and resilience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10932. doi:10.3390/ijerph191710932

15. Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol. 2001;50(3):337–421. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00062

16. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–524. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

17. Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(3):763–773.

18. Elemo AS, Ahmed AH, Kara E, Zerkeshi MK. The fear of COVID-19 and flourishing: assessing the mediating role of sense of control in international students. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021. doi:10.1007/s11469-021-00522-1

19. Hong JH, Lachman ME, Charles ST, et al. The positive influence of sense of control on physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health in older adults: an outcome-wide approach. Prev Med. 2021;149:106612. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106612

20. Wang W, Zhou K, Yu Z, Li J. The Cost of Impression Management to Life Satisfaction: sense of Control and Loneliness as Mediators. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:407–417. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S238344

21. Allemand M, Job V, Mroczek DK. Self-control development in adolescence predicts love and work in adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2019;117(3):621–634. doi:10.1037/pspp0000229

22. Zuo P-Y, Karremans JC, Scheres A, et al. A dyadic test of the association between trait self-control and romantic relationship satisfaction. Front Psychol. 2020;11:594476. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.594476

23. Hou Y, Hou W, Zhang Y, Liu W, Chen A. Relationship between working stress and anxiety of medical workers in the COVID-19 situation: a moderated mediation model. J Affect Disord. 2022;297:314–320. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.072

24. Li Z, Li J-B. The association between job stress and emotional problems in mainland Chinese kindergarten teachers: the mediation of self-control and the moderation of perceived social support. Early Educ Dev. 2020;31(4):491–506. doi:10.1080/10409289.2019.1669127

25. Pearlin LI. The sociological study of stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1989;30(3):241–256. doi:10.2307/2136956

26. Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: some conceptual perspectives. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(2):205–219. doi:10.1177/002214650504600206

27. Wu Q, Cao H, Lin X, Zhou N, Chi P. Child maltreatment and subjective well-being in Chinese emerging adults: a process model involving self-esteem and self-compassion. J Interpers Violence. 2021. doi:10.1177/0886260521993924

28. Wang L. The effects of cyberbullying victimization and personality characteristics on adolescent mental health: an application of the stress process model. Youth Soc. 2022;54(6):935–956. doi:10.1177/0044118x211008927

29. Brown RL, Ciciurkaite G. Disability, discrimination, and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a stress process model. Soc Ment Health. 2022;12(3):215–229. doi:10.1177/21568693221115347

30. Yu Y, Liu Z-W, Li T-X, Li Y-L, Xiao S-Y, Tebes JK. Test of the stress process model of family caregivers of people living with schizophrenia in China. Soc Sci Med. 2020;259:113113. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113113

31. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking Rumination. Perspectives Psychol Sci. 2008;3(5):400–424. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

32. Thomsen DK, Mehlsen MY, Olesen F, et al. Is There an Association Between Rumination and Self-Reported Physical Health? A One-Year Follow-Up in a Young and an Elderly Sample. J Behav Med. 2004;27(3):215–231. doi:10.1023/B:JOBM.0000028496.41492.34

33. Cropley M, Rydstedt LW, Devereux JJ, Middleton B. The relationship between work-related rumination and evening and morning salivary cortisol secretion. Stress Health. 2015;31(2):150–157. doi:10.1002/smi.2538

34. Türktorun YZ, Weiher GM, Horz H. Psychological detachment and work-related rumination in teachers: a systematic review. Educ Res Rev. 2020;31:100354. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100354

35. Weigelt O, Syrek CJ, Schmitt A, Urbach T. Finding peace of mind when there still is so much left undone—A diary study on how job stress, competence need satisfaction, and proactive work behavior contribute to work-related rumination during the weekend. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24:373–386. doi:10.1037/ocp0000117

36. Pauli R, Lang J. Collective resources for individual recovery: the moderating role of social climate on the relationship between job stressors and work-related rumination – a multilevel approach. German J Human Resource Management. 2021;35(2):152–175. doi:10.1177/23970022211002361

37. Feng X. How job stress affect flow experience at work: the masking and mediating effect of work-related rumination. Psychol Rep. 2022. doi:10.1177/00332941221122881

38. Vahle-Hinz T, Mauno S, de Bloom J, Kinnunen U. Rumination for innovation? Analysing the longitudinal effects of work-related rumination on creativity at work and off-job recovery. Work Stress. 2017;31(4):315–337. doi:10.1080/02678373.2017.1303761

39. Minnen ME, Mitropoulos T, Rosenblatt AK, Calderwood C. The incessant inbox: evaluating the relevance of after-hours e-mail characteristics for work-related rumination and well-being. Stress Health. 2021;37(2):341–352. doi:10.1002/smi.2999

40. Gossmann K, Schmid RF, Loos C, Orthmann ABA, Rosner R, Barke A. How does burnout relate to daily work-related rumination and well-being of psychotherapists? A daily diary study among psychotherapeutic practitioners. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1003171. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1003171

41. Gillet N, Austin S, Huyghebaert-Zouaghi T, Fernet C, Morin AJS. Colleagues’ norms regarding work-related messages: their differential effects among remote and onsite workers. Personnel Rev. 2022. doi:10.1108/PR-01-2022-0067

42. He Y, Walker JM, Payne SC, Miner KN. Explaining the negative impact of workplace incivility on work and non-work outcomes: the roles of negative rumination and organizational support. Stress Health. 2021;37(2):297–309. doi:10.1002/smi.2988

43. Crain TL, Schonert-Reichl KA, Roeser RW. Cultivating teacher mindfulness: effects of a randomized controlled trial on work, home, and sleep outcomes. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22:138–152. doi:10.1037/ocp0000043

44. Cropley M, Dijk D-J, Stanley N. Job strain, work rumination, and sleep in school teachers. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2006;15(2):181–196. doi:10.1080/13594320500513913

45. DeJong H, Fox E, Stein A. Does rumination mediate the relationship between attentional control and symptoms of depression? J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2019;63:28–35. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.12.007

46. Hsu KJ, Beard C, Rifkin L, Dillon DG, Pizzagalli DA, Björgvinsson T. Transdiagnostic mechanisms in depression and anxiety: the role of rumination and attentional control. J Affect Disord. 2015;188:22–27. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.008

47. Cox RC, Olatunji BO. Linking attentional control and PTSD symptom severity: the role of rumination. Cogn Behav Ther. 2017;46(5):421–431. doi:10.1080/16506073.2017.1286517

48. Cen YS, Su S, Dong Y, Xia LX. Longitudinal effect of self-control on reactive-proactive aggression: mediating roles of hostile rumination and moral disengagement. Aggress Behav. 2022;48(6):583–594. doi:10.1002/ab.22046

49. Li JB, Dou K, Situ QM, Salcuni S, Wang YJ, Friese M. Anger rumination partly accounts for the association between trait self-control and aggression. J Res Pers. 2019;81:207–223. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2019.06.011

50. Ross ND, Kaminski PL, Herrington R. From childhood emotional maltreatment to depressive symptoms in adulthood: the roles of self-compassion and shame. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;92:32–42. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.016

51. Barboza GE, Siller LA. Child maltreatment, school bonds, and adult violence: a serial mediation model. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(11–12):NP5839–NP5873. doi:10.1177/0886260518805763

52. Cropley M, Michalianou G, Pravettoni G, Millward LJ. The relation of post-work ruminative thinking with eating behaviour. Stress Health. 2012;28(1):23–30. doi:10.1002/smi.1397

53. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

54. Hendrick SS. A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. J Marriage Family. 1988;50(1):93–98. doi:10.2307/352430

55. Wang J, Wang X. Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus(2nd Ed.). John Wiley & Sons; 2020.

56. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford; 2011.

57. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach.

58. Prem R, Kubicek B, Diestel S, Korunka C. Regulatory job stressors and their within-person relationships with ego depletion: the roles of state anxiety, self-control effort, and job autonomy. J Vocat Behav. 2016;92:22–32. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.004

59. Joel S, Eastwick PW, Allison CJ, et al. Machine learning uncovers the most robust self-report predictors of relationship quality across 43 longitudinal couples studies. Proce National Acad Sci. 2020;117(32):19061–19071. doi:10.1073/pnas.1917036117

60. Yucel D, Latshaw BA. Spillover and crossover effects of work-family conflict among married and cohabiting couples. Soc Ment Health. 2020;10(1):35–60. doi:10.1177/2156869318813006

61. Li Y, Zhang R-C. Kindergarten teachers’ work stress and work-related well-being: a moderated mediation model. Soc Behav Pers. 2019;47(11):1–11. doi:10.2224/sbp.8409

62. Agyapong B, Brett-MacLean P, Burback L, Agyapong VIO, Wei Y. Interventions to reduce stress and burnout among teachers: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(9):5625.

63. Zheng Y, Gu X, Jiang M, Zeng X. How might mindfulness-based interventions reduce job burnout? Testing a potential self-regulation model with a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness. 2022;13(8):1907–1922. doi:10.1007/s12671-022-01927-2

64. Karabinski T, Haun VC, Nübold A, Wendsche J, Wegge J. Interventions for improving psychological detachment from work: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol. 2021;26(3):224–242. doi:10.1037/ocp0000280

65. Bernstein EE, Heeren A, McNally RJ. Unpacking rumination and executive control: a network perspective. Clin Psychol Sci. 2017;5(5):816–826. doi:10.1177/2167702617702717

66. van der Meij L, Gubbels N, Schaveling J, Almela M, van Vugt M. Hair cortisol and work stress: importance of workload and stress model (JDCS or ERI). Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;89:78–85. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.12.020

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.