Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

“Who Knows Me Understands My Needs”: The Effect of Home-Based Telework on Work Engagement

Authors Wang H, Xiao Y, Wang H, Zhang H, Chen X

Received 30 December 2022

Accepted for publication 28 February 2023

Published 6 March 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 619—635

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S402159

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Hui Wang,1 Yuting Xiao,2 Hui Wang,3 Han Zhang,1 Xueshuang Chen1

1Business School, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, 411105, People’s Republic of China; 2Business school, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610000, People’s Republic of China; 3School of Public Administration, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, 411105, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Hui Wang, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Based on the affective event theory and the theoretical framework of “work environment features–work events–emotional responses-work attitude”, this study aims to explore how and when home-based telework negatively affects work engagement by focusing on the dual chain mediating paths of “workplace isolation–negative emotion” and “telepressure–negative emotion”, and the moderating role of family-supportive leadership.

Methods: A questionnaire survey was used to collect 276 self-reported responses from employees with home-based telework experience in China.

Findings: (a) Home-based telework indirectly and negatively affects work engagement through the mediating chain of “workplace isolation–negative emotion”; (b) Home-based telework indirectly and negatively affects work engagement through the mediating chain of “telepressure–negative emotion”; (c) Family-supportive leadership negatively moderates the chain mediating effect of “workplace isolation–negative emotion” and “telepressure–negative emotion” between home-based telework and work engagement. In other words, the higher the level of family-supportive leadership, the weaker the negative effect of home-based telework on work engagement.

Originality/Value: This study sheds additional light on the relationship between home-based telework and work engagement by constructing the influence mechanism model of home-based telework on work engagement, in which “workplace isolation–negative emotion” and “telepressure–negative emotion” act as chain mediators, and family supportive leadership as moderator. This study enriches the literature on home-based telework.

Practical Implications: The findings indicates that home-based work has indirectly and negatively effects on work engagement through dual chain mediating paths of “workplace isolation–negative emotion” and “telepressure–negative emotion”. However, family-supportive leadership can weaken this negative influence. Therefore, organizations need to cultivate family supportive leadership.

Keywords: home-based telework, workplace isolation, telepressure, negative emotion, work engagement, family supportive leadership

Introduction

The organizational interior work pattern has evolved with the development of information and communication technologies (ICT) and the advent of online office software. Paid work has become “flexible” and no longer related only to specific geographical settings. In other words, propelled by ICT, paid work can be done anytime and anywhere. Telework, a flexible work arrangement that allows employees to carry out paid work in another place (eg, home, neighborhood work centers and satellite centers) instead of the office, has become a reality. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, home-based telework, a common form of telework, was generally used to reward employees with high performance or was allowed for those who volunteered to work from home as a family-supportive welfare policy. For organizations, home-based telework is considered to improve productivity, reduce employment costs and improve employee morale. In contrast, for individuals, home-based telework is reported to balance work and life, reduce annoying commute travel, and increase work autonomy. Much of the existing literature before 2020 reflects report and focused on outcomes such as productivity,1–4 satisfaction with teleworking,5–7 job autonomy8–10 and work-family balance.11–16

Recently, however, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread, the background of home-based telework was shifted. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the nature of work, and required an urgent review of where work is performed. Organizations were encouraged to implement home-based telework to ensure continuity of operations in an emergency. Therefore, home-based telework has become an urgent work arrangement for organizations to cope with the effects of external shocks, rather than a work arrangement negotiated by employers and employees under a voluntarily.17 More and more people were included in the home-based telework arrangement, irrespective of whether their equipment and environment are appropriate, bringing new challenges to organizational management. Some employees have been caught unprepared in the face of the sudden change of work. Limited by factors such as personal qualities and work environment, some employees have difficulty adapting to home-based telework. The number of literature on home-based telecommuting has rapidly increased after 2020,18–24 focusing on the advantages and disadvantages of home-based telework. More specifically, these studies concluded that home-based telework could benefit some employees by providing them with increased job autonomy and helping them reduce their commuting frequency to reduce their job stress and enhance their job satisfaction.25–27 On the other side, during the COVID-19 pandemic, home-based telework could also be destructive to the productivity, work engagement and well-being of employees with no prior telework experience due to low ICT self-efficacy, social isolation, and the difficulty of maintaining a work-life balance when home-based telework.28–33 Other studies have shown the negative effects of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic on physical27 and mental health outcomes.34,35

However, in previous literature, little is known about the relationship between home-based telework and employee work engagement. Peters et al10 found that teleworking has the potential to increase work engagement by increasing job autonomy. Sardeshmukh et al36 concluded that the influence of teleworking on work engagement has both a bright side and a dark side. Specifically, teleworking could increase work engagement through increased job autonomy and reduced role conflict, and decrease work engagement through reduced support, reduced feedback, and increased role ambiguity. These research10,36 conclusions on the relationship between home-based telework and work engagement are derived mainly from the perspective of the job demand-resource model However, those factors, such as whether telework is voluntary, leading to the unfixed relationship between home-based telework and work engagement, are not discussed in previous findings.10,36 With the prevalence of COVID-19, more and more employees are working from home involuntarily. Thus, employees’ emotional responses to home-based telework should be discussed and more empirical research is needed to analyze how and when home-based telework affects work engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic.37

This study seeks to address this theoretical gap by developing a theoretical model based on affective event theory to explore how and when home-based telework affects work engagement. According to affective event theory, work environment features will lead to work events and affect individuals’ attitudes and behavior by stimulating individuals to produce corresponding emotional responses.38 On the one hand, home-based telework may lead to workplace isolation perceived by teleworkers due to decreased face-to-face communication with their leaders and coworkers.4,39 Moreover, workplace isolation can lead to negative emotions, such as anxiety. On the other hand, the dependence on electronic communication during working from home is significantly enhanced. Although electronic communication provides convenience for organizational members, teleworkers may face many problems, such as online information overload40 and high response expectations from the sender.41 Consequently, employees under greater telepressure are more likely to generate negative emotions, such as dissatisfaction or irritability.42 Furthermore, individuals in a negative emotional state have less psychological potential to allocate. Thus, their work engagement level is relatively lower.43

Given the negative effects of home-based telework on employees’ work engagement, how to weaken such negative effects of home-based telework is a more important issue for organizations to implement teleworking arrangements successfully. Affective event theory indicates leadership style is an important component of the organizational environment,38 while leaders are the specific executors of organizational policies. Therefore, leaders’ understanding and attitude to home-based telework are significant for whether the policy can achieve the expected effect. Prior studies have shown that home-based telework decreases the opportunities for employees to get emotional support.44 However, leaders’ support can enhance their sense of self-worth and positive emotion to help alleviate the effects of negative events on them.45 Family supportive leadership, which is a leadership style in which the supervisor supports subordinates in handling work and family affairs to maintain work-family balance, can provide targeted support in both work and family.46 Family-supportive leadership can establish close emotional ties between teleworkers and their supervisors and help them cope better with work stress through emotional support, instrumental support, and so on. As a result, teleworkers could save valuable resources and focus on their work.47 Consequently, family-supportive leadership negatively moderated the chain mediating effect of workplace isolation and negative emotion between home-based telework and work engagement, and also negatively moderated the chain mediating effect of telepressure and negative emotion between home-based telework and work engagement.

Overall, according to affective event theory, and based on the framework of “work environment features–work events–emotional responses-work attitude”, this study explored the influence mechanism of home-based telework on work engagement, in which “workplace isolation—negative emotion” and “telepressure—negative emotion” as chain mediators, and the possible moderating effect of family supportive leadership are also discussed. Thus, this study has the following contributions. First, this study enriches the research of home-based telework. Previous literature focused mostly on the positive effects of home-based telework on work engagement. This study explores the possible negative effect of home-based telework on work engagement. Second, based on affective event theory, this study built on the perspective of emotion by using it to shed additional light on the relationship between home-based telework and work engagement. This study constructed an analysis framework by two chain mediators: “workplace isolation-negative emotion” and “telepressure-negative emotion” to clarify the influence mechanism of home-based telework on work engagement, which further explains how home-based telework affects work engagement. Third, this study expanded the boundary conditions of the effects of home-based telework on work engagement, and extended the application research of family-supportive leadership.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Home-Based Telework

Telework is a flexible work arrangement where employees can work in alternative locations away from the central office through modern information technology.48 It can be categorized according to alternative locations into home-based telework, mobile telework, etc.49 Compared with the latter, home-based telework is more common. It connects more closely with individuals’ family lives.

Prior scholars have discussed the antecedents and outcomes of home-based telework. In particular, the factors influencing the implementation of home-based telework include organizational and individual characteristics. For instance, Mayo et al50 pointed out that home-based telework is a major deviation from traditional work, which may bring uncontrollable risks and higher coordination costs to a firm. Therefore, home-based telework can be widely implemented when top managers attach importance to work-family balance. Moreover, supervisors who manage teleworkers directly face more work demands and are compelled to spend more time on communication and supervision. As a result, a home-based telework plan may be hindered by the low level of supervisor support.51 Gender, high education, family composition, and individual willingness also affect the implementation and effect of telework.13,52

Research on the outcomes of home-based telework has focused mainly on work-family conflict, job performance, job satisfaction, work well-being, mental and physical health, and so on.2,10,11,13,26,27,53 Some scholars have found that home-based telework not only helps relieve commuting time stress13 and reduce work-family conflict,2 it also improves individual job satisfaction and job performance by enhancing employees’ autonomy and perceived supervisor support.3,10 However, other studies have suggested that home-based telework will trigger work-family conflict11,54 and that the separation of time and space caused by telework will harm employees’ job performance by reducing their willingness and frequency of knowledge sharing.55 In addition, the decrease in face-to-face communication causes teleworkers to miss informal information and implicit learning chances, and hence, they have to devote more energy to self-improvement.56 Employees have difficulty gaining Evidence shows that teleworkers get less support from organizational members39 and have lower work well-being.33

Home-Based Telework and Negative Emotion

First, because of the invisibility of home-based telework, employees carry out more self-management and self-leadership for worry of losing supervisors’ trust or failing to keep pace with colleagues, such as proactively extending working hours and increasing workload.57 Nevertheless, the extension of actual working hours to evenings or weekends and the use of information technology to complete tasks during non-working hours make it difficult for teleworkers to achieve psychological detachment42 but can also easily trigger work-family conflict.55 As a result, teleworkers are more likely to feel tired and mentally depleted, leading to negative emotions.58

Second, the transformation of work mode brought by technological progress places higher requirements and challenges on employees’ digital ability. However, some employees who are limited by personal qualities cannot adapt to this new work. Teleworkers need to face more complex work requirements and norms, which may increase the difficulty of multi-tasking. Employees will experience more task frustration,59 and will encounter more difficulties in obtaining timely and effective support.3 Hence, teleworkers are more likely to produce negative emotions like anger.

H1: Home-based telework is positively related to negative emotion.

Mediating Role of Workplace Isolation Between Home-Based Telework and Negative Emotion

Workplace isolation is defined as a relatively hidden form of workplace conflict related to the lack of emotional connection, trust, and support between organizational members, and includes two dimensions: colleague isolation and company isolation. The former refers to reduced affective interaction with colleagues and indifferent interpersonal relationships. In contrast, the latter refers to the difficulty in gaining attention and recognition from supervisors and the limited vocational development.60 Based on affective event theory, home-based telework greatly reduces the social interactions among organizational members, which will increase the possibility of workplace isolation and more easily induce individual negative emotions more easily.

Home-based telework causes employees to experience intense workplace isolation. Teleworkers are spatially separated from other organizational members, and their connections rely on digital communication rather than offline activities. The decrease in informal and face-to-face communication makes it tough to establish and maintain positive emotional contact with supervisors or colleagues. Thus, they receive less support.56 In addition, teleworkers’ task completion processes can be difficult to be observed directly or indirectly by their co-workers. The insufficiency of complete information to evaluate contributions and abilities can easily lead to “flexibility bias” and coldness toward teleworkers. In addition, supervisors tend to trust office workers but ignore teleworkers, resulting in reduced recognition and promotion chances.39

Individuals suffering from workplace isolation are at risk of loss of positive emotional resources. They are more likely to fall into negative emotions after encountering negative events, while workplace isolation usually means low-quality interpersonal relationships, development bottlenecks, and a lack of supportive resources. Such problems will increase teleworkers’ psychological pressure, which may reduce their sense of belonging and identity to the organization43 and increase their uncertainty about future career development.

H2: Workplace isolation positively mediates the relationship between home-based telework and negative emotion.

Mediating Role of Telepressure Between Home-Based Telework and Negative Emotion

Following Barber and Santuzzi,42 this study defines telepressure as how individuals are forced to respond quickly to online information based on ICTs. There are two types of pressure: subjective, which refers to the psychological pressure perceived by the individual, and objective, which refers to the factual pressure exerted by others. This study refers to the latter. Other organizational members may put forward higher requirements for the response speed of electronic messages of employees working from home. Thus, teleworkers must frequently reply to online messages, resulting in excessive consumption of energy and enthusiasm and further producing negative emotions like dissatisfaction and irritability.

Teleworkers communicate with others mainly online through various social media. If the information exchange is not timely, the work progress will be affected, which is not conducive to completing tasks. Therefore, supervisors and colleagues often impose high expectations of response speed for teleworkers, requiring them to reply to work information quickly.41 Some social work platforms have also introduced “read” and reminder functions, which aggravate the time pressure of teleworkers and force them to respond to received online messages immediately.44 Moreover, teleworkers may have higher motivation for impression management because of the worry of disadvantages in promotion and performance. Therefore, they will adopt positive response strategies to improve their self-image and thus experience greater telepressure.42

Excessive telepressure makes employees pay close attention to social media such as DingTalk and WeChat. The overloaded use of social media will consume a large amount of their attention and energy resources,61 resulting in a decline in their ability to control emotions.62 Furthermore, people under high telepressure tend to suspend their tasks and respond to information immediately when receiving online messages. Such frequent interruptions can seriously interfere with work thinking and cause employees to be more irritable and dissatisfied.42

H3: Telepressure positively mediates the relationship between home-based telework and negative emotion.

Negative Emotion and Work Engagement

Negative emotion is a subjective experience of depression, including anxiety, sadness, and other unpleasant emotional feelings.63 Some studies have confirmed that negative emotions can affect work attitude and behavior.43,64–66 When individuals are in a negative emotional state, their internal motivation will be damaged to a certain extent due to unsatisfied cognitive and emotional needs, thereby losing their enthusiasm and interest in work resulting in an avoidance attitude43 and an unwillingness to devote more spiritual and psychological resources to work. Furthermore, individuals who experience more negative emotions have less emotional, cognitive and other resources, lower sense of energy, and are more likely to experience fatigue, powerlessness and other feelings, thus reducing work engagement.66

H4: Negative emotion is negatively related to work engagement.

Double Chain Mediation Effect

Affective event theory indicates that work environment features lead to positive or negative events. Individuals have corresponding emotional reactions driven by work events that eventually affect their work attitude and behavior. When individuals are in a negative emotional state, their intrinsic motivation will be damaged to a certain extent because of dissatisfaction with cognitive and emotional needs. As a result, they lose their enthusiasm and interest and produce an avoidance attitude at work.43 At the same time, employees need to invest more resources to resist the influence of negative emotions, making them feel more tired and powerless, reducing the resources used for work engagement.

As discussed above, on the one hand, unpleasant events such as being alienated and neglected by supervisors or colleagues due to working from home can stimulate teleworkers to have negative emotions, further weakening their internal motivation to engage in work actively. On the other hand, employees working from home generally face high response expectations from others. Hence, they need to reply to received electronic messages at once. Such telepressure makes them suffer from negative emotions like anxiety and tension, which would decrease work engagement.

H5a: Home-based telework is negatively related to work engagement through the chain mediation of “workplace isolation-negative emotion.”. H5b: Home-based telework is negatively related to work engagement through the chain mediation of “telepressure-negative emotion.”.

Moderating Effect of Family-Supportive Leadership

Family-supportive leadership is a win-win leadership style, specifically referring to employees’ need to balance the relationship between work and family and displaying family-supportive behaviors, including emotional support, instrumental support, role modeling, and creative work-family management.46 It has certain limitations that general supportive leadership only concentrates on supporting employees to fulfill their job roles. However, family-supportive leadership emphasizes the support for both work and family, which could help employees to achieve a harmonious relationship between work and family.

According to affective event theory, family-supportive leadership reflects a leader’s care for subordinates’ work and family conditions. It can meet teleworkers’ emotional needs of being respected and recognized, thus helping to suppress the occurrence of workplace isolation during telework situations. First, high-level family supportive leaders pay attention to emotional support for teleworkers. They will attach importance to communication with remote employees and affirm their contribution and effort to work in a timely manner.67 Such emotional support can enhance trust and commitment on both sides and help improve the closeness of teleworkers to the organization,68 thereby alleviating and reducing possible isolation from colleagues and the company. Second, high-level family support leaders place a high premium on instrumental support for employees who work from home. Finally, they provide training and guidance for teleworkers to adapt to telework. For instance, they arrange flexible work tasks to enhance job autonomy, organize digital ability training to improve remote work competence, and so on. These factors are conducive to raising teleworkers’ perceived organizational support.69

On the contrary, when family support leadership is low, teleworkers’ emotional and instrumental support is insufficient. Specifically, the lack of attention, communication, and training would bring about a feeling of being ignored by organizations. Teleworkers may feel they are being unfairly treated in performance appraisal and promotion, further increasing workplace isolation.70

Furthermore, family-supportive leadership can moderate the chain mediating effect of workplace isolation and negative emotion between home-based telework and work engagement by mitigating the negative effect of home-based telework on workplace isolation. When leaders have a high level of family support, they can not only put themselves in the perspective of teleworkers to think but also advocate for greater understanding and inclusion among other members. As a result, teleworkers are less isolated in the workplace and experience fewer negative emotions. Thus, the indirect negative effect of home-based telework on work engagement through workplace isolation and negative emotion is weakened.

H6a: Family-supportive leadership negatively moderated the relationship between home-based telework and workplace isolation. H6b: Family-supportive leadership negatively moderated the chain mediating effect of workplace isolation and negative emotion between home-based telework and work engagement.

Likewise, family-supportive leaders understand the needs of teleworkers in the family. They can tolerate and forgive the behavior of not responding to online messages in time, which helps to relieve the tension and pressure. High-level family-supportive leaders realize that employees cannot put all their time into work. Therefore, they are willing to help employees integrate work and family roles, allowing teleworkers to interrupt work temporarily according to their needs and delaying reply information. These behaviors help ease the teleworkers’ anxiety and tension.71 Conversely, family-supportive leaders at a low level are less likely to separate work from family. They assume that employees can be available even during non-working hours,72 which makes teleworkers need to focus on multiple social work platforms simultaneously and stay online at all times, thereby greatly increasing their remote stress.

Furthermore, family-supportive leadership at a high level can moderate the chain mediating effect of telepressure and negative emotion between home-based telework and work engagement by weakening the negative effect of home-based telework on telepressure. Leaders who actively support families emphasize the harmony between work and family. They believe that employees can finish work conscientiously without constant supervision and do not need to prove it by responding to online information at once. Hence, they have relatively low expectations for teleworkers’ responses. Moreover, the trust of leaders enables teleworkers to deal with received electronic information more easily and calmly under pressure to maximize the saving of emotional resources and put them to work.73

H7a: Family-supportive leadership negatively moderated the relationship between home-based telework and telepressure. H7b: Family-supportive leadership negatively moderated the chain mediating effect of telepressure and negative emotion between home-based telework and work engagement.

The theoretical model of this study is shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical Model. |

Methods

Sample and Procedure

This study conducted a questionnaire survey online in China to test the theoretical model. Data were collected in August 2021. Participants met the following criteria: Participants working as enterprise employees who had experience of home-based telework to varying extents (>0%). Participants were recruited through the professional questionnaire research platform “Credamo” for the snowball method. The survey was conducted following the strictest ethical rules for research. All participants were informed that the survey was anonymous and the data will only be used for academic research. A total of 346 questionnaires were eventually collected. From this number, 70 questionnaires were discarded for patterned responses (eg, selecting the midpoint or alternating between options) or random responses, leaving 276 valid questionnaires with a response rate of 79.77%.

Among the samples, 107 (38.77%) are males and 169 (61.23%) are females. In terms of age, 177 (64.13%) are 20–30 years old, 77 (27.9%) are 31–39 years, and 22 (7.97%) are over 40 years. In terms of education, 45 (16.3%) have a junior college degree, 194 (70.29%) have a bachelor’s degree, while 37 (13.41%) reached a master’s degree or above. In terms of working seniority, 169 (61.23%) have worked for less than 5 years, 76 (27.54%) have worked for 6–9 years, and 31 (11.23%) have worked for more than 10 years. In terms of job position, 75 (27.17%) worked in R&D, 42 (15.22%) worked in administrative, 40 (14.49%) employed in financial, 34 (13.04%) are from human resource management, 32 (11.59%) worked in marketing, and 53 (19.20%) are worked in other job positions. In terms of industry, 72 (26.09%) were in IT industry, 25 (9.06%) were in the financial industry, 46 (16.66%) were in the manufacturing industry, 32 (11.59%) were in the management consulting industry, and 61 (22.10%) were in other industries.

Measures

All scales’ items were originally developed in English and were therefore translated into Chinese. All scales’ items except home-based telework and negative emotion, are measured on a five-point Likert scale from 1= “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”.

Home-Based Telework

Home-based telework was measured with a scale developed by Golden.8 The variable is measured through the extent of average weekly working hours at home. The range is from 0% to 100%. The special item is “What percentage of average hours do you spend working from home in the total working hours per week.”

Family Supportive Leadership

Family supportive leadership was measured with the four-item scale developed by Hammer et al74 The items are: (1) My leader makes me feel comfortable talking to them about the conflicts between work and non-work. (2) My leader demonstrates effective behaviors in how to juggle work and non-work issues. (3) My leader works effectively with employees to creatively solve conflicts between work and non-work. (4) My leader organizes the work in my department or unit to jointly benefit employees and the company (Cronbach’s α=0.869).

Workplace Isolation

Workplace isolation was measured with the ten-item scale developed by Marshall et al60 Sample items are “I have friends available to me at work”, “I have one or more co-workers available who I talk to about day-to-day problems at work”, “I am well integrated with the department/company where I work”, “Upper management knows about my achievements” (Cronbach’s α=0.944).

Telepressure

Telepressure was measured with a six-item scale developed by Barber et al,42 and include an inverse item. Respondents were asked to answer the reaction when they received electronic messages from colleagues or leaders. The items such as: “It’s hard for me to focus on other things when I receive a message from someone”, “I can concentrate better on other tasks once I have responded to my messages” (Cronbach’s α=0.908).

Negative Emotion

Negative emotion was measured with a five-item scale of Liu et al75 Respondents had to evaluate the average frequency they experienced following emotions while working from home (1=Never; 2=Seldom; 3=Sometimes; 4=Often; 5=Always). A sample item is “My work makes me anxious” (Cronbach’s α=0.939).

Work Engagement

Work engagement was assessed with the nine-item scale from Breevaart et al76 Participants were asked to judge their work while working from home. The items such as: “At my work, I feel bursting with energy”, “I am enthusiastic about my job” (Cronbach’s α=0.955).

Control Variables

We controlled for employees’ gender, age, education, working seniority, job position and industry to rule out their potential confounding effects in the model, as those are the variables commonly controlled for in telework research26,53,77 and demographics are found to be related to work engagement.

Data Analysis

In this study, SPSS 23.0 and Mplus 7.0 were used to test the research model. SPSS 23.0 was used to analyze the reliability and descriptive statistics of the key variables except home-based telework, while Mplus 7.0 was used for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), common method variance (CMV), and path analysis. The mediation effect was computed for 5000 bootstrapped samples, and 95% confidence intervals were also computed. To calculate the moderating effect, the independent variables and moderating variables were mean-centered. The moderated chain mediating effect was tested by whether the confidence interval of coefficient product values contained zero.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Mplus 7.0 was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis of the key variables. Compared with other competition models, the theoretical six-factor model (home-based telework, family supportive leadership, workplace isolation, telepressure, negative emotion, work engagement) had a better fit with the observed data (χ2/df=1.611, RMSEA=0.047, CFI=0.957 TLI=0.953, SRMR=0.051) (see Table 1). CFA results indicates that the six-factor model has satisfactory convergent and discriminant validity.

|

Table 1 Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

Common Method Variance (CMV)

This study tested common method variance by controlling for unmeasured latent method factor. Specifically, a potential common factor including all items was added to the six-factor model and compared with the six-factor model. If the fitting index becomes worse or does not improve significantly, it indicates the I of severe CMV. Comparing the six-factor model with the latent common factor model, the χ2/df of latter increased, which means the fitting index become worse (see Table 1). In sum, CMV in this study is not a serious problem.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 2 showed the results of descriptive statistics and correlations. Home-based telework was positively correlated to negative emotion (r = 0.425, p<0.01), workplace isolation (r = 0.394, p<0.01), and telepressure (r = 0.434, p<0.01). Workplace isolation and telepressure was positively correlated to negative emotion (r = 0.589, p<0.01; r = 0.416, p<0.01). Negative emotion was negatively correlated to work engagement (r = −0.622, p<0.01). The above results preliminarily supported the research hypotheses.

|

Table 2 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations |

Hypothesis Testing

To test the theoretical model, we conducted structural equation model using Mplus 7.0 for path analysis (see Figure 2). The results showed a positive association between home-based telework and negative emotion (β = 0.165, p<0.01), and thus, H1 was confirmed. Negative emotion is negatively related to work engagement (β = −0.363, p<0.01), and thus, H4 was supported.

|

Figure 2 Path Analyses Results. Note: N=276; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. |

As shown in Table 3, we found significant indirect effect of home-based telework on negative emotion through workplace isolation (β=0.165, CI= [0.099, 0.246]), thus, H2 was supported. Meanwhile, telepressure also played a mediating role between home-based telework and negative emotion (β=0.82, CI= [0.025, 0.139]), thus H3 was supported. Table 4 presented the results of the chain mediation effect analysis. The indirect effect of “HBTW→WI→NE→WE” was significant (β=−0.063, CI= [−0.098, −0.027]), H5a was supported. We also found the indirect effect of “HBTW→TP→NE→TP” was significant, hence H5b was confirmed.

|

Table 3 Bootstrap Test Results for the Mediating Effect |

|

Table 4 Bootstrap Test Results for the Chain Mediating Effect |

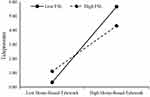

Figure 2 also presented the results of moderating effect test. The estimate of interaction of home-based telework and family-supportive leadership on workplace isolation was significantly negative (β=−0.165, p<0.01), supporting H6a. Furthermore, H7a predicted that family-supportive leadership also moderates the relationship between home-based telework and telepressure, which supported by the results (β=−0.116, p<0.05). To show the moderating effect more visually, the corresponding moderating effect diagrams were drawn in this study (see Figures 3 and 4).

|

Figure 3 Moderating Effect of Family-supportive Leadership on the Relationship between Home-based Telework and Workplace Isolation. Abbreviation: FSL, Family-supportive Leadership. |

|

Figure 4 Moderating Effect of Family-supportive Leadership on the Relationship between Home-based Telework and Telepressure. Note: FSL, Family-supportive Leadership. |

Finally, Table 5 showed the moderated chain mediating effect. At low FSL, the estimate of the chain mediating effect of “HBTW→WI→NE→TP” was −0.250, while the estimate was −0.486 at high FSL. The difference between the two groups was significant (β=0.236, CI= [0.065, 0.507]), and H6b was confirmed. In addition, Table 5 also showed that FSL negatively moderated the chain mediating effect of “HBTW→TP→NE→TP.” At low FSL, the estimate of the chain mediating effect was −0.196. However, the estimate of the chain mediating effect was −0.317 at high FSL. The two groups had significant difference (β=0.121, CI= [0.023, 0.316]), supporting H7b.

|

Table 5 Bootstrap Test Results for Moderated Chain Mediating Effect |

Discussion

This study aimed to understand how and when home-based telework negatively affects work engagement. Building on affective event theory, this study crafted a theoretical framework to explore the influence mechanism of home-based telework on work engagement. The results of the empirical study support the proposed research model, and the main findings are as follows:

First, home-based telework is indirectly and positively related to negative emotions via workplace isolation and telepressure. On the one hand, due to the lack of face-to-face communication and the invisibility of the work process, it is difficult for home-based teleworkers to maintain emotional ties with colleagues, resulting in less support from the organization perceived by home-based teleworkers, and more workplace isolation perceived by home-based teleworkers, thus, lead to negative emotions such as anxiety. On the other hand, because communication in home based telework is mainly realized through social work media such as WeChat, home-based teleworkers are more likely to face high response expectations from leaders or colleagues, which leads to higher perceived telepressure and are more prone to negative emotions such as fidgety.

Second, home-based telework is negatively and indirectly related to work engagement through two chain paths. Both “workplace isolation-negative emotion” and “telepressure-negative emotion” mediate between home-based telework and work engagement. Individuals who experience more negative emotions have less emotional, cognitive and other resources, lower sense of energy, and are more likely to experience fatigue, powerlessness and other feelings, thus reducing work engagement.66 On the one hand, home-based teleworkers have less face-to-face communication with their leaders and colleagues, resulting in workplace isolation. On the other hand, home-based teleworkers must face high response expectations from their leaders and colleagues, leading to telepressure. Both workplace isolation and telepressure are unpleasant events, that can stimulate home-based teleworkers to have negative emotions, further weak their internal motivation and enthusiasm for work, thus decreasing work engagement.

Third, family-supportive leadership moderates the relationship between home-based telework and workplace isolation and the relationship between home-based telework and telepressure. Family-supportive leadership can directly enhance home-based teleworkers’ perceived support from their leaders. Family-supportive leadership can also convey to the organization members that leaders attach importance to home-based telework by reshaping the pro-employee working atmosphere, which could help reduce workplace isolation and telepressure.

Fourth, family-supportive leadership negatively moderates the chain mediating effect of “workplace isolation-negative emotion” and “telepressure-negative emotion” between home-based telework and work engagement. Social support from leaders can greatly improve the resilience of teleworkers, help them effectively resist the negative effects of workplace events such as being neglected by colleagues or leaders, being forced to respond to received messages at once, and better save emotional resources to devote to work. As a result, they will be more willing and able to pay attention to work actively.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several potential limitations. First, the extent to which individuals with diverse characteristics are affected by negative events differ. Future research could consider factors, such as work-family division preference and psychological capital in the study framework. Second work motivation may affect teleworkers’ work engagement. From the motivation perspective, home-based telework can be divided into active and passive telework. Future research could explore the effects of home-based telework on work engagement from the motivation perspective. Third, leadership and family support are important sources of social support. The moderating effect of family support can be explored further to improve the boundary conditions of home-based telework affect work engagement in future research. Lastly, although anonymous measurement method design in survey were used to reduce CMV in this study, cross-sectional study could trigger CMV. Future researches could use longitudinal designs to further improve the accuracy of conclusions.

Conclusion

Theoretical Contributions

This study makes several theoretical contributions.

First, this study extends the current understanding of home-based telework. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, teleworking was usually carried out with work arrangements negotiated by employees and employers on a voluntarily. Much of the existing literature before 2020 reflects this, with a focus on outcomes such as work performance,4 satisfaction with teleworking,5,6 and work-family balance.12,13 As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, home-based teleworking is widely adopted by organizations, which meant employees who rarely or never have home-based telework experience and involuntary to work from home are required to do so, irrespective of whether their equipment and environment are appropriate. The number of literature on home-based telework has rapidly increased after 2020, focusing on outcomes such as productivity,31 well-being,29,30,33,78 job satisfaction,27 job stress,18 work-life balance,21 physical health27,79 and mental health outcomes.34,35,54 However researches on work engagement is scarce.29,32 This study explores the relationship between home-based telework and work engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings will enrich the literature on home-based work and work engagement.

Second, this study built upon the perspective of emotion by using it to shed additional light on the relationship between home-based telework and work engagement. This study constructed an analysis framework by two chain mediators: “workplace isolation-negative emotion” and “telepressure-negative emotion” to clarify the influence mechanism of home-based telework on work engagement, which further explains how home-based telework affect work engagement. Despite previous literature having confirmed the negative relationship between home-based telework and work engagement, it is based mainly on the perspective of identity.36 However, with the prevalence of COVID-19, more and more employees are compelled to work from home. Facing the sudden change of work, some employees showed a decline in work engagement and experienced emotional exhaustion.29,32 Therefore, this study provided a new theoretical perspective for revealing how home-based telework affects work engagement based on the affective event theory, and provided empirical support for the probably negative relationship between home-based telework and work engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Third, this study expanded the boundary conditions of the effects of home-based telework on work engagement and extended the application research of family-supportive leadership. Current research suggests that leadership support can improve employees’ self-worth, and positive emotions reduce the effects of negative events.45 Compared with generalized supportive leadership, family-supportive leadership focuses on promoting balance between work and family and can provide more targeted support for teleworkers.46 Nevertheless, the existing research on home-based telework lacks attention on family-supportive leadership, and thus family-supportive leadership was incorporated into this study as a moderator. The findings of this study confirmed that family-supportive leadership negatively moderated the chain-mediating effect of workplace isolation and negative emotion between home-based telework and work engagement and negatively moderated the chain-mediating effect of telepressure and negative emotion between home-based telework and work engagement. The findings of this study expanded the boundary conditions of the impact of home-based telework on work engagement, and extended the application research of family-supportive leadership.

Practical Implications

The current research provides important practical implications for better application of home-based telework in enterprises. Given the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, an increasing number of companies passively implement home-based telework, forcing parts of unprepared and involuntary employees to get involved. Practically, it results in the decline of employees’ work engagement, damaging enterprise performance. Hence, managers need to understand why such a matter happened and take action to prevent it.

Our research findings suggest the following. First, companies are supposed to improve the benefits associated with flexible work, optimize home-based telework procedures and clarify the scope and time of telework. Compared with the central office, people who work from home are separated from the organization in time and space. Their rights and welfare are difficult to guarantee effectively, and their task they face is also relatively more difficult. For instance, teleworkers may not have access to a specific network, and thus, they cannot obtain the necessary data for work. The online meeting progress is also hindered by the limitations of network and electronic devices. The lack of printing equipment will also affect the completion of tasks to a certain extent. Therefore, enterprises should pay more attention to teleworkers and build a pro-employee organizational culture and an inclusive work environment. Specifically, on the one hand, improving the internet facilities, providing small printers and other office supplies for teleworkers in need, and rewarding employees with office-related electronic equipment should be ensured. On the other hand, teleworkers’ job responsibilities should be clarified. Further, the online work process needs to be simplified, and corresponding performance appraisal indicators and evaluation systems should be formulated for teleworkers.

Second, organizations should cultivate leaders’ family support behavior and increase emotional and instrumental support for employees. The leader is not only the spokesman of an organization but also the direct executor of the telework policy. Therefore, the attitude and behavior of leaders toward flexible work will greatly affect employees. Consequently, leaders should enhance communication with teleworkers, which should be routine and daily. In addition, they should familiarize themselves with subordinates’ work and family situations and affirm their contributions to work and organization in a timely manner. Leaders can also provide necessary digital skills training and telework guidance for teleworkers, granting them more autonomy in work content and schedule. Moreover, teleworkers should be asked to share their successful experience in solving workplace conflicts and alleviating work pressure. Such behaviors can enhance teleworkers’ psychological security and help them maintain positive and stable moods at work.

Third, leaders should lower their expectations of home-based teleworkers and help them actively cope with pressure. Communication between teleworkers, their leaders, and colleagues relies mainly on social media like WeChat and DingTalk. This process has questions, such as untimely information exchange, which may lead to missing messages or delayed responses. Moreover, it is difficult for managers to monitor teleworkers in time dynamically and the teleworkers performance tend to be judged based on how quickly they respond to online information and punish subordinates who do not. As a result, teleworkers may face more demands on the speed of message response and inevitably experience negative emotions. To avoid the negative consequences associated with telepressure, managers should objectively consider varieties of work and non-work interference while working at home, advocate for other organizational members to enhance their trust and understanding of teleworkers, and reduce their requirements in responding. Teleworkers should be provided with a certain amount of time buffer and decrease the frequency of unnecessary online meetings and electronic monitoring. In particular, leaders can help teleworkers relieve pressure by cutting their work tasks appropriately and adjusting the work arrangement.

Fourth, from the perspective of employees, they can choose a suitable telework mode according to their conditions and make long-term career development plans. However, an individual’s digital ability can be challenging while working from home. Some employees not only do not adapt well to such kind of work arrangement but are also prone to interference. They may experience more frustration in cross-departmental cooperation and multi-tasking. Because of the decreased frequency of interaction among organizational members and the invisible working process, teleworkers are prone to conflict with others, so they may be treated with prejudice and a cold shoulder. One critical method comprehensively considers whether employees have strong self-control and emergency handling ability and whether they can master digital office software to determine the appropriate home-based telework hours. Another method is actively adapting to the trend of the digital office, making improvement plans, and strengthening the control of emotions. Furthermore, teleworkers could keep emotional contact with other members through online or offline social activities to promote mutual trust and understanding.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethical Statement

This research was approved by the ethical review committees of Xiangtan University in China. We confirm that the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participant(s) to publish this paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Disclosure

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

1. Aguilera A, Lethiais V, Rallet A, Proulhac L. Home-based telework in France: characteristics, barriers and perspectives. Transport Res A Pol. 2016;92:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2016.06.021

2. Gajendran RS, Harrison DA. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(6):1524–1541. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524

3. Gajendran RS, Harrison DA, Delaney‐Klinger K. Are telecommuters remotely good citizens? Unpacking telecommuting’s effects on performance via i‐deals and job resources. Pers Psychol. 2015;68(2):353–393. doi:10.1111/peps.12082

4. Nakrošienė A, Bučiūnienė I, Goštautaitė B. Working from home: characteristics and outcomes of telework. Int J Manpower. 2019;40(1):87–101. doi:10.1108/IJM-07-2017-0172

5. Golden TD, Veiga JF. The impact of superior–subordinate relationships on the commitment, job satisfaction, and performance of virtual workers. Leadership Quart. 2008;19(1):77–88. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.12.009

6. Smith SA, Patmos A, Pitts MJ. Communication and teleworking: a study of communication channel satisfaction, personality, and job satisfaction for teleworking employees. Int J Bus Commun. 2018;55(1):44–68. doi:10.1177/2329488415589101

7. Wheatley D. Good to be home? Time-use and satisfaction levels among home-based teleworkers. New Tech Work Employ. 2012;27(3):224–241. doi:10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00289.x

8. Golden TD. The role of relationships in understanding telecommuter satisfaction. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(3):319–340. doi:10.1002/job.369

9. Musson G, Tietze S. Feelin’ groovy?: appropriating time in home‐based telework. Cult Organ. 2004;10(3):251–264. doi:10.1080/14759550412331297174

10. Peters P, Poutsma E, Van der Heijden BI, Bakker AB, de Bruijn T. Enjoying new ways to work: an HRM‐process approach to study flow. Hum Resour Manag Us. 2014;53(2):271–290. doi:10.1002/hrm.21588

11. Delanoeije J, Verbruggen M, Germeys L. Boundary role transitions: a day-to-day approach to explain the effects of home-based telework on work-to-home conflict and home-to-work conflict. Hum Relat. 2019;72(12):1843–1868. doi:10.1177/0018726718823071

12. Dockery AM, Bawa S. When two worlds collude: working from home and family functioning in Australia. Int Labour Rev. 2018;157(4):609–630. doi:10.1111/ilr.12119

13. Lapierre LM, Van Steenbergen EF, Peeters MC, Kluwer ES. Juggling work and family responsibilities when involuntarily working more from home: a multiwave study of financial sales professionals. J Organ Behav. 2016;37(6):804–822. doi:10.1002/job.2075

14. Madsen SR. The effects of home‐based teleworking on work‐family conflict. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2003;14(1):35–58. doi:10.1002/hrdq.1049

15. Madsen SR. Work and family conflict: can home-based teleworking make a difference? Int J Organ Theory Behav. 2006;9(3):307–350. doi:10.1108/IJOTB-09-03-2006-B002

16. Peters P, den Dulk L. Cross cultural differences in managers’ support for home-based telework: a theoretical elaboration. Int J Cross Cult Man. 2003;3(3):329–346. doi:10.1177/1470595803003003005

17. Moretti A, Menna F, Aulicino M, Paoletta M, Liguori S, Iolascon G. Characterization of home working population during COVID-19 emergency: a cross sectional analysis. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2020;17(17):62–84. doi:10.3390/ijerph17176284

18. Adamovic M. How does employee cultural background influence the effects of telework on job stress? The roles of power distance, individualism, and beliefs about telework. Int J Inform Manag. 2002;62:102437. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102437

19. Barnes SJ. Information management research and practice in the post-COVID-19 world. Int J Inform Manag. 2020;55:102175. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102175

20. Chamakiotis P, Panteli N, Davison RM. Reimagining e-leadership for reconfigured virtual teams due to Covid-19. Int J Inform Manag. 2021;60:102381. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102381

21. Dwivedi YK, Hughes DL, Coombs C, Constantiou I, Duan Y, Upadhyay N. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: transforming education, work and life. Int J Inform Manag. 2020;55:102211. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102211

22. Papagiannidis S, Harris J, Morton D. WHO led the digital transformation of your company? A reflection of IT related challenges during the pandemic. Int J Inform Manag. 2020;55:102166. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102166

23. Sharma A, Sasser T, Gonzalez ES, Vander Stoep A, Myers K. Implementation of home-based telemental health in a large child psychiatry department during the COVID-19 crisis. J Child Adol Psychop. 2020;30(7):404–413. doi:10.1089/cap.2020.0062

24. Venkatesh V. Impacts of COVID-19: a research agenda to support people in their fight. Int J Inform Manag. 2020;55:102197. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102197

25. Delanoeije J, Verbruggen M. Between-person and within-person effects of telework: a quasi-field experiment. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2020;29(6):795–808. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2020.1774557

26. Lott Y, Abendroth AK. Affective commitment, home‐based working and the blurring of work–home boundaries: evidence from Germany. New Tech Work Employ. 2022;21:1–21. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12255

27. Sousa-Uva M, Sousa-Uva A, Serranheira F. Telework during the COVID-19 epidemic in Portugal and determinants of job satisfaction: a cross-sectional study. Bmc Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12295-2

28. Abdel Hadi S, Bakker AB, Häusser JA. The role of leisure crafting for emotional exhaustion in telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;34(5):530–544. doi:10.1080/10615806.2021.1903447

29. Galanti T, Guidetti G, Mazzei E, Zappalà S, Toscano F. Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: the impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(7):426–432. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002236

30. Heiden M, Widar L, Wiitavaara B, Boman E. Telework in academia: associationswith health and well-being among staff. Internet High Educ. 2021;81(4):707–722. doi:10.1007/s10734-020-00569-4

31. Kazekami S. Mechanisms to improve labor productivity by performing telework. Telecommun Policy. 2020;44(2):101868. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101868

32. Nagata T, Nagata M, Ikegami K, Hino A, Mori K. Intensity of home-based telework and work engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(11):907–912. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002299

33. Song Y, Gao J. Does telework stress employees out? A study on working at home and subjective well-being for wage/salary workers. J Happiness Stud. 2020;21(7):2649–2668. doi:10.1007/s10902-019-00196-6

34. Schmitt JB, Wulf T, Breuer J. From cognitive overload to digital detox: psychological implications of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;124:106899. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106899

35. Xiao Y, Becerik‑Gerber B, Lucas G, Roll SC. Impacts of working from home during COVID‑19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of office workstation users. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(3):181. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002097

36. Sardeshmukh SR, Sharma D, Golden TD. Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: a job demands and job resources model. New Tech Work Employ. 2012;27(3):193–207. doi:10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00284.x

37. Gerards R, de Grip A, Baudewijns C. Do new ways of working increase work engagement? Pers Rev. 2018;47(2):517–534. doi:10.1108/PR-02-2017-0050

38. Weiss HM, Cropanzano R. Affective events theory. Res Organ Behav. 1996;18(1):1–74. doi:10.1177/030639689603700317

39. Beauregard TA, Basile KA, Canónico E. Telework: outcomes and facilitators for employees. In: Landers RN, editor. The Cambridge Handbook of Technology and Employee Behavior. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2019:511–543.

40. Shockley KM, Allen TD, Dodd H, Waiwood AM. Remote worker communication during COVID-19: the role of quantity, quality, and supervisor expectation-setting. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(10):1466–1482. doi:10.1037/apl0000970

41. Cambier R, Vlerick P. You’ve got mail: does workplace telepressure relate to email communication? Cogn Technol Work. 2020;22(3):633–640. doi:10.1007/s10111-019-00592-1

42. Barber LK, Santuzzi AM. Please respond ASAP: workplace telepressure and employee recovery. J Occup Health Psych. 2015;20(2):172. doi:10.1037/a0038278

43. Burić I, Macuka I. Self-efficacy, emotions and work engagement among teachers: a two wave cross-lagged analysis. J Happiness Stud. 2018;19(7):1917–1933. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9903-9

44. Jo JK, Harrison DA, Gray SM. The ties that cope? Reshaping social connections in response to pandemic distress. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(9):1267–1282. doi:10.1037/apl0000955

45. Asgari S. The influence of varied levels of received stress and support on negative emotions and support perceptions. Curr Psychol. 2016;35(3):386–396. doi:10.1007/s12144-015-9305-2

46. Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Yragui NL, Bodner TE, Hanson GC. Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). J Manag. 2009;35(4):837–856. doi:10.1177/0149206308328510

47. Matthews RA, Mills MJ, Trout RC, English L. Family-supportive supervisor behaviors, work engagement, and subjective well-being: a contextually dependent mediated process. J Occup Health Psych. 2014;19(2):168–181. doi:10.1037/a0036012

48. Ollo-López A, Goñi-Legaz S, Erro-Garcés A. Home-based telework: usefulness and facilitators. Int J Manpower. 2021;42(4):644–660. doi:10.1108/IJM-02-2020-0062

49. Neirotti P, Paolucci E, Raguseo E. Mapping the antecedents of telework diffusion: firm‐level evidence from Italy. New Tech Work Employ. 2013;28(1):16–36. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12001

50. Mayo M, Gomez-Mejia L, Firfiray S, Berrone P, Villena VH. Leader beliefs and CSR for employees: the case of telework provision. Leadership Org Dev J. 2016;37(5):609–634. doi:10.1108/LODJ-09-2014-0177

51. Park S, Cho YJ. Does telework status affect the behavior and perception of supervisors? Examining task behavior and perception in the telework context. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2022;33(7):1326–1351. doi:10.1080/09585192.2020.1777183

52. Pigini C, Staffolani S. Teleworkers in Italy: who are they? Do they make more? Int J Manpower. 2019;40(2):265–285. doi:10.1108/IJM-07-2017-0154

53. Liu L, Wan W, Fan Q. How and when telework improves job performance during COVID-19? Job crafting as mediator and performance goal orientation as moderator. Psychol Res Behav Ma. 2021;14:2181–2195. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S340322

54. Graham M, Weale V, Lambert KA, Kinsman N, Stuckey R, Oakman J. Working at home: the impacts of COVID 19 on health, family-work-life conflict, gender, and parental responsibilities. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(11):938–943. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002337

55. Van der Meulen N, van Baalen P, van Heck E, Mülder S. No teleworker is an island: the impact of temporal and spatial separation along with media use on knowledge sharing networks. J Inf Technol Uk. 2019;34(3):243–262. doi:10.1177/0268396218816531

56. Weinert C, Maier C, Laumer S. Why are teleworkers stressed? An empirical analysis of the causes of telework-enabled stress. Wirtschaftsinformatik Proc. 2015;2015:1407–1421.

57. Suh A, Lee J. Understanding teleworkers’ technostress and its influence on job satisfaction. Internet Res. 2017;27(1):140–159. doi:10.1108/IntR-06-2015-0181

58. Butts MM, Becker WJ, Boswell WR. Hot buttons and time sinks: the effects of electronic communication during nonwork time on emotions and work-nonwork conflict. Acad Manage J. 2015;58(3):763–788. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0170

59. Chong S, Huang Y, Chang D. Supporting interdependent telework employees: a moderated-mediation model linking daily COVID-19 task setbacks to next-day work withdrawal. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(12):1408–1422. doi:10.1037/apl0000843

60. Marshall GW, Michaels CE, Mulki JP. Workplace isolation: exploring the construct and its measurement. Psychol Mark. 2007;24(3):195–223. doi:10.1002/mar.20158

61. Orhan MA, Castellano S, Khelladi I, Marinelli L, Monge F. Technology distraction at work. Impacts on self-regulation and work engagement. J Bus Res. 2021;126:341–349. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.048

62. Johnson A, Dey S, Nguyen H, Groth M, Harvey SB. A review and agenda for examining how technology-driven changes at work will impact workplace mental health and employee well-being. Aust J Manag. 2020;45(3):402–424. doi:10.1177/0312896220922292

63. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

64. Greenidge D, Coyne I. Job stress or sand voluntary work behaviors: mediating effect of emotion and moderating roles of personality and emotional intelligence. Hum Resour Manag J. 2014;24(4):479–495. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12044

65. Kearns SM, Creaven AM. Individual differences in positive and negative emotion regulation: which strategies explain variability in loneliness? Personal Ment Health. 2016;11(1):64–74. doi:10.1002/pmh.1363

66. Wang F, Shi W. The effect of work-leisure conflict on front-line employees’ work engagement: a cross-level study from the emotional perspective. Asia Pac J Manag. 2020;39:1–23. doi:10.1007/s10490-020-09722-0

67. Shi Y, Xie J, Zhou ZE, et al. Family-supportive supervisor behaviors and employees’ life satisfaction: the roles of work-self facilitation and generational differences. Int J Stress Manag. 2020;27(3):262–272. doi:10.1037/str0000152

68. Pan SY, Chuang A, Yeh YJ. Linking supervisor and subordinate’s negative work–family experience: the role of family supportive supervisor behavior. J Leadersh Org Stud. 2021;28(1):17–30. doi:10.1177/1548051820950375

69. Choi J, Kim A, Han K, Ryu S, Park JG, Kwon B. Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction with work–family balance: a moderating role of perceived insider status. J Organ Behav. 2018;39(1):1–11. doi:10.1002/job.2205

70. Rofcanin Y, Las Heras M, Bakker AB. Family supportive supervisor behaviors and organizational culture: effects on work engagement and performance. J Occup Health Psych. 2017;22(2):207–217. doi:10.1037/ocp0000036

71. Aryee S, Chu CW, Kim TY, Ryu S. Family-supportive work environment and employee work behaviors: an investigation of mediating mechanisms. J Manage. 2013;39(3):792–813. doi:10.1177/0149206311435103

72. Koch AR, Binnewies C. Setting a good example: supervisors as work-life-friendly role models within the context of boundary management. J Occup Health Psych. 2015;20(1):82–92. doi:10.1037/a0037890

73. Xu S, Zhang Y, Zhang B, Qing T, Jin J. Does inconsistent social support matter? The effects of social support on work absorption through relaxation at work. Front Psychol. 2020;11:555501. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.555501

74. Hammer LB, Ernst Kossek E, Bodner T, Crain T. Measurement development and validation of the Family Supportive Supervisor Behavior Short-Form (FSSB-SF). J Occup Health Psych. 2013;18(3):285–296. doi:10.1037/a0032612

75. Liu C, Spector PE, Shi L. Cross‐national job stress: a quantitative and qualitative study. J Organ Behav. 2007;28(2):209–239. doi:10.1002/job.435

76. Breevaart K, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Hetland J. The measurement of state work engagement: a multilevel factor analytic study. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2012;28(4):305–312. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000111

77. Giménez-Nadal JI, Molina JA, Velilla J. Work time and well-being for workers at home: evidence from the American Time Use Survey. Int J Manpower. 2020;41(2):184–206. doi:10.1108/IJM-04-2018-0134

78. Curzi Y, Pistoresi B, Poma E, Tasselli C. The home-based teleworking: the implication on workers’ wellbeing and the gender impact. Rev Iberoam Econ. 2021;31:80–102.

79. Buomprisco G, Ricci S, Perri R, De Sio S. Health and telework: new challenges after COVID-19 pandemic. J Environ Public Health. 2021;5:2. doi:10.21601/ejeph/9705

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.