Back to Journals » Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology » Volume 16

Verrucous Granular Parakeratosis on the Groin: A Case Report

Authors Li H, Li H, Tian Q, Fang X

Received 22 February 2023

Accepted for publication 25 March 2023

Published 1 April 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 853—857

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S401799

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jeffrey Weinberg

Huixian Li,1 Hui Li,2 Qinghua Tian,2 Xiangang Fang2

1Department of Sterilization Supply, Weifang People’s Hospital, Weifang, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Dermatology, Weifang People’s Hospital, Weifang, Shandong, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xiangang Fang, Department of Dermatology, Weifang People’s Hospital, 151 Guangwen Street, Weifang, Shandong, 261041, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86-536-8192561, Email [email protected]

Abstract: Granular parakeratosis is a rare dermatosis characterized by erythematous scaly patches or papules, and plaques, often involving intertriginous areas. In this work, a 73-year-old Chinese male patient presented with a 6-month history of pruritic verrucous papules on the bilateral groin. A skin biopsy was performed and revealed the following: the horny layer showed highly compact hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with basophilic granules; the epidermis showed obvious acanthosis with psoriasiform hyperplasia. The final diagnosis was verrucous granular parakeratosis. We also reviewed the progress in nomenclature, etiology, clinical manifestations, differential diagnosis and treatment. Different clinical manifestations may represent different clinical entities. Dermatologists should differentiate it from other diseases to make a correct diagnosis. Treatment options should be based on the variable etiologies and clinical manifestations.

Keywords: granular parakeratosis, verrucous, papule, groin, glucocorticoid, tretinoin

Introduction

Granular parakeratosis (GP) is a rare-acquired self-limiting skin disease. GP presents clinically as hyperkeratotic erythematous scales or papules which combine to form plaques, mainly involving intertriginous areas.1,2 Given the rarity of GP, we report a case of verrucous GP in the groin of an elderly man to get attention of clinicians. The dermatologic examination revealed multiple gray-white or dark red verrucous papules on the bilateral groin. Histology showed highly compact hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis with basophilic granules and psoriasiform epidermis hyperplasia. We also reviewed the progress in nomenclature, etiology, clinical manifestations, differential diagnosis and treatment. Two main lesions types of GP were documented, including erythematous scales and papules (plaques). We considered that different clinical manifestations may represent different clinical entities.

Case Presentation

A 73-year-old Chinese male patient presented with a 6-month history of pruritic papules on the bilateral groin. The most potent steroid and antifungal ointments did not improve the eruptions before he sought evaluation at our hospital. The medical history was significant for a cerebral infarction. There was no family history of similar complaints. The dermatologic examination revealed multiple gray-white or dark red hyperkeratotic papules on a brown background on the bilateral groin. On closer examination, the hyperkeratotic papules had a verrucous appearance, some of which had coalesced. The papules were slightly hard on palpation (Figure 1). There were no abnormalities involving the axillae or perianal folds.

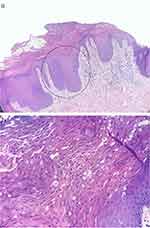

The possible diagnosis included viral warts, seborrheic keratoses, Bowenoid papulosis, Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, granular parakeratosis, and Langerhans histiocytosis. A skin biopsy was performed and revealed the following: the stratum corneum showed highly compact hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with basophilic granules; the epidermis showed obvious acanthosis with psoriasiform hyperplasia; and lymphocytes infiltrated around small vessels in the upper dermis (Figure 2). A fungal microscopic examination and culture were negative. Based on clinical manifestations and histopathologic features, the final diagnosis was verrucous GP. The skin lesions improved after 1 month of a topical glucocorticoid and tretinoin cream. There was no recurrences after 6 months of follow-up.

Discussion

GP is a rare skin disease characterized by erythematous scaly patches or papules, and plaques, predominantly involving intertriginous areas. GP was first described by Northcutt et al3 in 1991 as an axillary eruption with an exclusive histopathology and was named “axillary GP”. With the development of recognition of anatomical distribution, the naming has also evolved.4 In 1998, Mehregan et al5 reported a case involving the groin as intertriginous GP, omitting the word “axillary”. In 1999, Metze et al6 renamed it GP, acknowledging involvement in non-intertriginous areas and omitting the word “intertriginous”.

The etiology of GP is unclear, but many theories exist on the possible causes of GP. GP has been thought to respond to contact antiperspirants and is now considered a disorder of keratinization with an increasing number of potential pathogenic factors. The first theory proposed by Northcutt et al was that GP is a contact reaction to local products, resulting in the disruption of profilaggrin-to-filaggrin during epidermal keratinization.7 Normally, filaggrin maintains the keratohyaline granules in the stratum corneum during keratinization. On the basis of immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies,8 the retention of keratohyaline granules in GP may be attributed to defects in processing profilaggrin-to-filaggrin. Another view holds that GP is caused by an acquired keratosis disorder with unknown etiology and unrelated to contact. There are cases reported without the use of topical products.2 This theory is supported by the response of GP to isotretinoin therapy without identifying triggers.9,10 Recently, infection has been suggested as a possible cause, as the skin microbiome of some cases had changed and responded to oral antibiotics.11,12 For the above-mentioned, GP may be a response pattern rather than a unique disease entity.

Two main lesions types of GP were reported, including erythematous scales and papules (plaques).4 The first feature of GP is erythematous scales manifested as symmetrical erythema with pathognomonic multi-layer brown epidermal scales. Kumarasinghe et al first proposed the term hyperkeratotic flexural erythema as a better description for this type.11 The second feature of GP is papules which can coalesce into plaques with erythematous/brown coloring and hyperkeratotic texture. However, only 4 cases of verrucous GP, as a special subtype of papular GP, were reported by 2022.4 Most patients have itching, burning, tenderness and other symptoms, and a few patients are asymptomatic. The most common involved sites are intertriginous areas, such as the axilla and groin, most of which are bilateral. A small number of patients develop eruptions in non-intertriginous areas, such as the face, trunk and thighs.4

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of GP as erythematous scales includes other diseases, especially those involving the folds such as seborrheic dermatitis, candidiasis, inverse psoriasis, erythrasma, irritant or allergic contact dermatitis and Langerhans histiocytosis. The differential diagnosis of GP as papules includes Darier disease, pemphigus vegetans, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, viral warts, seborrheic keratoses and even Bowenoid papulosis.

With high clinical suspicion, a skin biopsy is required for histopathological diagnosis. The classic histology of GP is characterized by thickening of the stratum corneum with retention of keratohyalin granules. Other manifestations may include parakeratosis, hyperkeratosis, psoriatic or papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia, and superficial dermal lymphocyte infiltration.2,4 Different clinical manifestations, including erythematous scales and papules may have different pathological manifestations. However, it should be emphasized that GP can be just a nonspecific pathological change. Similar shows to GP are also described in other diseases such as dermatophytosis, molluscum contagiosum, actinic keratosis.13 Therefore, dermatologists need to combine clinical manifestations and pathological features to make appropriate diagnosis.

Because GP is rare, it is difficult to evaluate its therapeutic effect, and several cases of self-healing have been documented. According to previous reports, initial and important management includes identifying and removing external products and avoiding occlusion where possible. Second, many kinds of treatments have been used with different effects, including topical glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors, antibiotics, antifungals, vitamin D3 derivatives, ammonium lactate, tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, antibacterial agents and botulinum toxin injection. In other cases, physical therapies such as cryotherapy and Nd:YAG combined with CO2 fractional laser are also effective.1,4,13 Since the prognosis of GP is good and the efficacy varies greatly, treatment should be individualized according to clinical conditions. Different clinical manifestations including erythematous scales and papules may need different management. GP as erythematous scales termed as hyperkeratotic flexural erythema may respond to some topical drugs and oral antibacterial drugs.11,14 GP as papules may need stronger treatments such as tretinoin, and even some physical therapies.

Our patient was presented with multiple gray-white hyperkeratotic papules with an obvious verrucous appearance on the bilateral groin. The histologic features include a highly compact hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis with basophilic granules, and acanthosis with psoriasiform hyperplasia, so the diagnosis of verrucous GP on the groin was made. Based on the benign characteristics of GP, itching symptoms, lesion types and previous literature, we gave the patient combined use of a topical glucocorticoid and tretinoin cream, which has improved the lesions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, GP is a rare acquired cutaneous disease characterized by erythematous scales or hyperkeratotic papules typically involving intertriginous areas. The cause of GP is unknown and may be related to exposure to irritants. In our opinion, GP may be a reaction pattern rather than a distinct disease and different clinical manifestations may represent different clinical entities, which needs further research. GP should be differentiated from other skin diseases involving the intertriginous areas due to the rarity, and a histopathologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis. Now no standardized treatment is recommended, and treatment options should be based on the variable etiologies and clinical manifestations.

Institutional Approval

No institutional approval was required to publish the case details.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available.

Consent Statement

Signed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of the case details.

Disclosure

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare for this work.

References

1. Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495–500. doi:10.1007/s40257-015-0148-2

2. Scheinfeld NS, Mones J. Granular parakeratosis: pathologic and clinical correlation of 18 cases of granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:863–867. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.12.031

3. Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541–544. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70078-G

4. Ip KH, Li A. Clinical features, histology, and treatment outcomes of granular parakeratosis: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61(8):973–978. doi:10.1111/ijd.16107

5. Mehregan DA, Thomas JE, Mehregan DR. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:495–496. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70333-0

6. Metze D, Rutten A. Granular parakeratosis – a unique acquire disorder of keratinization. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:339–352. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01855.x

7. English JC, Derdeyn AS, Wilson WM, Patterson JW. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:330–332. doi:10.1007/s10227-002-0131-4

8. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology.

9. Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:S279–80. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.109252

10. Webster CG, Resnik KS, Guy F. Webster: axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:789–790.

11. Kumarasinghe SP, Chandran V, Raby E, Wood B. Hyperkeratotic flexural erythema responding to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid therapy: report of four cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:311–314. doi:10.1111/ajd.13069

12. Dear K, Gan D, Stavrakoglou A, Ronaldson C, Nixon RL. Hyperkeratotic flexural erythema (more commonly known as granular parakeratosis) with use of laundry sanitizers containing benzalkonium chloride. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(12):2196–2200. doi:10.1111/ced.15358

13. Lin Q, Zhang D, Ma W. Granular parakeratosis: a case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:1367–1370. doi:10.2147/CCID.S371558

14. Herat A, Gonzalez Matheus G, Kumarasinghe SP. Hyperkeratotic flexural erythema/granular parakeratosis responding to doxycycline. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63(3):368–371. doi:10.1111/ajd.13868

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.