Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 16

Validation of the Chinese Version Community’s Self-Efficacy Scale in Community-Dwelling Older Adults

Authors Zhang X, Li X, Luo W , Zhao H, Liu Y

Received 21 January 2022

Accepted for publication 7 April 2022

Published 19 April 2022 Volume 2022:16 Pages 1061—1070

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S359459

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Naifeng Liu

Xiuli Zhang,1,* Xuehan Li,2,* Wen Luo,3 Huiwen Zhao,3 Yan Liu4

1The 1st Ward of Joint Surgery Department, Tianjin Hospital, Tianjin, People’s Republic of China; 2Orthopaedics Department, Tianjin Jinnan Hospital, Tianjin, People’s Republic of China; 3The 2nd Ward of Joint Surgery Department, Tianjin Hospital, Tianjin, People’s Republic of China; 4The Community Health Service Center of Tianjin Economic-Technological Development Area, Tianjin, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Wen Luo; Huiwen Zhao, The 2nd Ward of Joint Surgery, Tianjin Hospital, 406 Jiefangnan Road, Tianjin, 300211, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86-22-131 1619 0054, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Background: The original study confirmed that the Japanese version of the community’s self-efficacy scale (CSES) may help to promote health policies, practices and interventions in the community. In China, research on the self-efficacy of community’s life is in its infancy. The aim of this study was to assess the validity, the reliability and the predictors of the Chinese version CSES in the aging population.

Methods: (1) Translation of the original Japanese version CSES into Chinese; (2) validation of the Chinese version in the aging population. Instrument measurement included reliability testing, item generation, construct validity and test–retest reliability. Confirmatory factor analysis was applied to determine construct validity and internal consistency. Meanwhile, we built the Bayesian network model of the Chinese version of CSES and determined target variables.

Results: Finally, 143 sample individuals have been included in this research. By confirmatory factor analysis, we confirmed that the Chinese version CSES fits a two-dimensional model. Additionally, this scale showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α coefficient 0.900) and test–retest reliability (kappa coefficient 0.754). The results of the Bayesian network model showed that the education (0.3278) and the perceived efficacy patient–physician interactions scale (0.2055) are important predictors of the CSES.

Conclusion: This is the first study to validate the Chinese version of CSES in older people. Our research confirmed that the Chinese version CSES has good internal consistency, construct validity and test–retest reliability. Meanwhile, patient’s confidence in communication with a physician and the patient’s educational level were the important predictors of community self-efficacy.

Keywords: community, self-efficacy, aging, validation

Background

The share of population over 60 years in the world constituted 11.7% in 2013, and will increase to 21.1% in 2050.1 About one-third of older adults in the world have experienced different degrees of loneliness or social isolation in their own life experience.2,3 Based on the report released by the National Bureau of Statistics, by the end of 2016, the number of older adults over 60 years in the People’s Republic of China has reached 231 million, accounting for 16.7% of the total population. It is the only country with an older adults population of more than 200 million in the world.4

Loneliness has been defined as a discrepancy between desired and real social relations, which results in decrease of quality of life and health status.5 Recent studies have borne out claims that gender, age, marital status, employment status, educational level, household income and urbanization process are social-demographic factors associated with loneliness and social relations.6 Meanwhile, the study confirmed that loneliness is one of the main risk factors of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).7 The scientific principles of how social isolation and loneliness impact on health are not understood, but are thought to include effects on health behaviors, sleep and social function.8 The results of previous studies showed a significant correlation between loneliness or negative social relationship and life expectancy reduction.9 Particularly for the older adults, the risk of social isolation increases with the decline of economic capacity, diseases, living alone and mobility inconvenience.10 Researches confirmed that participating in group activities can effectively prevent social loneliness.8,9 It can improve the quality of life, especially in older adults.

Self-efficacy is an important concept of social cognitive theory, which has been proposed by Bandura. It predicts a person's functioning by referring to the measure of the individual’s confidence towards a specific behavior.11 According to Bandura’s theory, self-efficacy reflects beliefs about an individuals’ ability for specific behaviors under domain-specific obstacles.12 In the aging population, higher self-efficacy was shown to be associated with better ability to improve quality of life, for example sleep and exercise. Traditionally, the support relationship in the community can positively affect the social participation and social capital of the older adults.13 In contrast, poor interpersonal relationships can make it difficult to obtain support, especially for the older adults living alone.14 The study confirmed that the Japanese version Community’s Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES) has sufficient reliability and validity in assessing community self-efficacy to help prevent social isolation of the older adults.15 The CSES was a novel instrument with good psychometric properties for assessing the community members’ self-efficacy to prevent social isolation among older adults. The CSES would prevent social isolation among older adults in communities and promote public well-being in aging societies. The Japanese version of CSES has two factors. The factor 1 included 4 items to measure the self-efficacy of a community network, building a community network and community. The factor 2 also included 4 items to measure the self-efficacy of neighborhood watch, keeping watch over older adults in the neighborhood and neighbors' safety. The scale may help to promote health policies, practices and interventions in the community. It may help prevent social isolation among the older adults and contribute to the overall well-being of Japan’s aging society.15 China is the world’s most populous country, and as the population ages, the social needs and requirement for spiritual solace of older adults are becoming augmented day by day. In China, research on the self-efficacy of community’s life is in its infancy. Until now, no available scale has been used to measure the older adults’ self-efficacy of community’s life in China.

To date, the Japanese version CSES has shown good structural validity and internal consistency in clinical samples of older people. Hence, the aim of this study was to assess the validity, reliability and the predictors of the Chinese version CSES in the aging population.

Availability of data and material: No additional data are available.

Methods

Design

This is an observational research study by a cross-sectional survey and is divided into two steps: (1) translating the Japanese version CSES into Chinese; (2) validating the Chinese version CSES in a sample between June and October in 2020.

Data Collection

According to the requirement of confirmatory factor analysis, we collected the sample data between June and October 2020. The ideal number of samples of confirmatory factor analysis should be above 10 times the number of items. In this study, the number of samples has exceeded the ideal standard.

Participants

The Hospital Research Ethics Committee approved the research program, and subjects provided the consent forms to participation. At the beginning of this study, the participants were informed about the participants’ rights and the investigators’ obligations. Researchers used uniform advice language to explain the points for filling the scales. All scales have been filled out by participants. The privacy of the participants have been protected during the study.16

The survey was sent between June and October in 2020 to a random sample of 150 individuals at three Community Health Centers in Tianjin. We selected persons in the database randomly.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Comprehension ability and consciousness; (2) Refer to the WHO standard: young older adults: 60–75 years; old older adults: 76–90 years; oldest old: over 90 years old.2 The Chinese Geriatrics Association standard classifies people over 65 people as the older adults.4 The age requirement was 65 years of age or older. (3) Have good living capacity, Barthel Index17 (BI) > 60; and (4) Written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Nervous system diseases; and (2) Symptoms which make the patient unable to communicate with others.16

The self-administered questionnaire has been used in this study. Prior to this, the investigators explained the considerations of the survey and obtained respondents’ consent. During the survey, personal privacy has been protected, and all scales have been collected within 10 minutes. At the end of the survey, participants were asked if they would like to complete the Chinese version of CSES a second time after about 2 weeks. The 2–3-week interval between the repeated measurement used in study is often used to assess test–retest reliability, so this study chose 2 weeks as the period to ensure that the sample was not lost.

Translation of the Chinese Version of CSES

The original Japanese version CSES consisted of 8 items, which had been divided into two dimensions – community network and neighborhood watch, respectively. The original version CSES has been published in English. Each item is scored between 0 and 3 (0 = not confident at all, 1 = slightly unconfident, 2 = slightly confident, 3 = completely confident),15 providing a total score of the CSES from 0 to 24, with 24 representing the best community self-efficacy.

Each item of the original version CSES has been translated into the initial Chinese version by two researchers who have advanced medical education background. After that, the initial Chinese version has been translated back to Japanese, and reviewed by the original author (Tadaka). According to advice, the final Chinese version CSES has been finalized after discussion. The final Chinese version CSES consists of 8 items and assesses the confidence for the performance of older people in community living also on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3.

Other Scales for Validation

The Perceived Efficacy of Patient–Physician Interactions scale (PEPPI-10) has been designed to measure the person’s confidence when they are communicating with physicians.18 The scale uses the Likert 11-grade scoring method (from 0 = no confidence to 10 = very confident). The higher score indicates better interaction ability with physician. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the English version PEPPI-10 was 0.91,18 which provides the reliable feasibility for clinical research. Studies confirmed that the Chinese version PEPPI-10 has good internal consistency in persons with knee osteoarthritis (Cronbach’s α coefficient 0.907).19

The Self-Efficacy for Exercise scale (SEE) has been developed by Resnick et al and can detect and appraise persons’ self-efficacy for exercise, with a high internal consistency.20 The Chinese version SEE has been validated and used in related studies (Cronbach’s α coefficient 0.75).21 This scale consists of nine items, which used the Likert 10-grade scoring method (between 0 = no confidence at all and 9 = very confident). A high score indicates better confidence on exercise in daily living.

The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) was developed by Blumenthal et al22 in 1987 and is used to assess the degree of individuals’ support from family, friends, leaders, colleagues and relatives. There were 12 items in the scale, including 4 items measuring support within the family and 8 items measuring support outside the family. Each item was assigned a score of 1–7 from “extremely disagree” to “extremely agree”.23 Scores less than 32 indicate that an individual’s social support system (for example family) is poor and does not provide help when they need it; scores between 32 and 50 indicate that an individual’s social support has some problems, but it is not serious.

Statistical Analysis

In this study, we first used the SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, 2010) to analyze the missing data and frequency of the project after data collection. We use LISREL 8.70 (scientific software international, Lincoln wood, Illinois, USA) to test the structural validity by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We checked the distribution characteristics of CSES to test the normality of the total score and determine the possible lower and upper limit effects. If more than 15% of the patients scored the worst or best in CSES, there was a lower or upper limit effect.24 In order to test whether the items of the Chinese version CSES measures fit a two-dimensional structure, the data were fitted to a two-factor model. Considering the order of the items, the robust maximum likelihood estimation with Satorra–Bentler (SB) scaled statistics has been used.25 In addition to SB chi-square statistics (SB χ2), the model fitting has been tested by non-standard fitting index (NNFI), comparative fitting index (CFI), standard root mean square residual (SRMR) and root mean square error (RMSEA). NNFI and CFI values ≥0.95, SRMR and RMSEA values ≤0.08 and 0.06, respectively, indicate that the model has good fitting.26,27

Cronbach’s α coefficient has been used to evaluate the internal consistency in validating the scale. Cronbach’s α coefficient has been one of the most important measurements in validity.28 The score range of Cronbach’s α coefficient was from 0 to 1, and high score indicates better internal consistency of the scale. The study confirmed that the Cronbach’s α coefficient is an effective index for the validation study of scale.29 Cronbach’s α coefficient >0.7 represented that the scale has good internal consistency, which could be used in clinical research.30 We used the kappa score to assess the test–retest reliability of the Chinese version CSES.31 Test–retest reliability, using the Cohen’s kappa, has been used to evaluate the level of agreement32 (from 0 to 1): 0.0–0.20: slight; 0.21–0.40: fair; 0.41–0.60: moderate; 0.61–0.80: substantial; 0.81–1.0: perfect.

In the end, we set up a Bayesian network model between the CSES and other variables in this study. First of all, we collected the original data, including data cleaning, data conversion, processing missing values and so on. The main scores and assignments in the study are shown in Table 1. Secondly, using IBM SPSS modeler 18.0 software, the Bayesian network data mining model was established. Based on the clinical investigation database of this study, a CSES database was established. The type selection flag is filtered and imported into the Bayesian network. The TAN model was used for structure type, Bayesian adjustment for small cell count was used as parameter learning method, expert was selected as model, prepossessing steps including feature selection was selected and only complete record was used for missing values. Significance level was 0.01. Compared with the traditional logistic regression model, the Bayesian network model has the following advantages: (1) it can clearly and intuitively show the dependence between variables; (2) when the evidence is input to any variable, the Bayesian network structure can update the probability of all other variables in the model, so as to realize the dynamic adjustment of the model; (3) the requirement of variables is not high, and the conditional independent hypothesis of prediction variables is relaxed, which makes full use of data, and makes up for the sensitivity of logistic regression to missing data; (4) it is more convenient to research the interaction of variables.33

|

Table 1 The Main Variables and Assignments |

Result

Participants

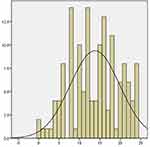

Overall, 150 participants were recruited and seven were excluded because of missing items. The evaluable population comprised 143 persons with mean age 70.85±4.6 years, and 58% were male. The median score of participants in the Chinese version CSES was 13.79, and the standard deviation was 6.1. Other sample characteristics are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 1. The sample of 143 participants all completed the measurements again 2 weeks later.

|

Table 2 Sample Characteristics (N=143) |

|

Figure 1 Individuals’ CSES score distribution. |

Results of the Adaptation Phase

During the adaptation process of the CSES, the researchers were influenced by the Japanese cultural background. Through discussion and communication with the original author, the members of the Expert Committee reached a consensus on the most appropriate expression to help participants understand the scale.34 Table S1 presents the translated results and process of the Chinese version CSES. All members of the Expert Committee believe that the aim of translating an accurate Chinese version CSES has been achieved.

Structural Validity, Internal Consistency and Test–Retest Reliability

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed that the final Chinese version CSES fits indices for two-dimensional model (chi-square=29.25, df=19, P value=0.062, RMSEA (90% CI)=0.062 (0.0; 0.1), SB χ2 (19)=1.54, NNFI=0.99, CFI=0.99, SRMR=0.038). Standardized factor loading ranged between 0.71 for item 6 and 0.89 for item 2, and the correlation coefficient between the two factors was 0.68 (Figure 2). The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the Chinese version CSES was 0.900, which indicates the Chinese version CSES has high internal consistency. Thus, the results confirmed that the Chinese version CSES fits two-dimensional model. No sample was missing in the second investigation. With substantial kappa coefficient (0.754) (Table 3), the rest–retest reliability of the Chinese version CSES has substantial agreement. Meanwhile, Bland–Altman analysis showed that the limits of agreement were from −3.6 to 3.5 in test–retest reliability, which was rather narrow (Figure 3).

|

Table 3 Symmetry Measure of the Chinese Version CSES |

|

Figure 2 Standardized factor loading and residuals for the items of the Chinese version CSES. |

|

Figure 3 Individual agreement between test and retest scores of the Chinese version CSES. |

Bayesian Network Model

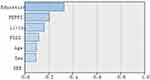

Figure 3 shows that the blue node represents the output node, that is, the score of the Chinese version Community’s Self-Efficacy Scale. It is the parent node of other nodes. The color of nodes is darker, that is more important, which represents the importance of input variables. It can be seen from the network that among the factors influencing the CSES, the importance of each factor is different. Among them, education (0.3278) and PEPPI (0.2055) are the main predictive variables of the CSES, while other factors had a relatively small impact. A visual display of the importance of variables is shown in Figures 4 and 5.

|

Figure 4 The Bayesian network model of the community’s self-efficacy scale. |

|

Figure 5 The Bayesian network structure of the Chinese version CSES. |

Discussion

The results of this study confirm that the Chinese version CSES is valid and reliable to assess confidence in community living. The Chinese version CSES can be used as an evaluation tool to measure the community’s well-being in old age, because it is simple and has good validity and reliability. Meanwhile, the study confirms that the Chinese version CSES fits two-dimensional model – the same as the original study.

Confirmatory factor analysis indicates that the Chinese version CSES was a two-dimensional construct. All indices of this study completely fit for two-dimensional model. This research demonstrated that the Chinese version CSES has high internal consistency, also indicating that the scale can be used in clinical study. Cronbach’s α coefficient of the original version CSES has been the same as reported and suggested that the CSES has sufficient precision for researches and population comparisons. The clinicians could accurately assess older adults’ confidence in different community activities by CSES.

Test–retest reliability is a very important index for discriminating between results in the sample.29 According to the test–retest reliability of this study, our results showed that the kappa coefficient of the Chinese version CSES was 0.754, indicating satisfactory test–retest reliability in two measurements. Furthermore, the test–retest reliability in this research was carried out within 2 weeks of the first survey, meaning that no inter-individual variation occurred.

In this research, Bayesian network model is constructed to screen the predictive variables of CSES score, and three important variables are finally screened out. According to the final model diagram, the education level and the PEPPI are the main parent nodes of CSES, indicating that the results mainly depend on these three variables. The results further confirmed that the education level of the older adults is closely related to their quality of life. Older adults with higher education would have better ability for community activities and communication with physician. Furthermore, the clinician could use the pre-determine to determine the self-efficacy of older adults on community activities and communication by this Bayesian network model.

The limitations of this study are: that (1) samples have been screened from a single center, so the diversity of samples cannot be guaranteed; and (2) the prediction performance of the model is reduced due to the simple selection of prediction variables and no artificial discretization. In spite of these limitations, we believe that the Chinese version CSES has good validity and reliability in an aging population. The number of sample is low in this study, which may influence the power of the evidence. The accuracy of item location is fully guaranteed in the study,20 besides, the Chinese version CSES is well-targeted, so the requirements of the sample size are reduced.16

Conclusion

This study confirmed that the Chinese version Community’s Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES) has good validity and reliability in an aging population. It can be used in assessing the level of self-efficacy in participating in community activities. Meanwhile, we found that the self-efficacy of communication with physician and the educational level are the important predictors of the self-efficacy on participating in community activities in older adults.

Abbreviations

PEPPI, perceived efficacy patient–physician interactions scale; SEE, self-efficacy for exercise scale; CSES, community’s self-efficacy scale; PSSS, perceived social support scale.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the Ethical Guidelines by the Chinese Government and the National Health Commission prohibit researchers from providing their research data to other third-party individuals.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The current study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Tianjin Hospital (No. TJYY-2020-YLS-043) and has been conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research by the Chinese Government. All study participants provided written informed consent by the completion and submission of the survey.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor ET at Department of Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Yokohama City University for consultation on the back translation of the CSES. This is a cross-cultural study, and the original version of the CSES has been published by Professor ET on BMC Public Health. The Chinese version of the CSES has not been published previously.

Funding

This study was supported by Tianjin Nursing Academy (TNA) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No: tjhlky2020YB01; PI:HWZ).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

1. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World population aging. New York: DESA; 2013.

2. Victor CR, Scambler SJ, Bowling ANN, et al. The prevalence of, and risk factors for, loneliness in later life: a survey of older people in Great Britain. Ageing Soc. 2005;25:357–375. doi:10.1017/S0144686X04003332

3. Yang K, Victor C. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing Soc. 2001;31:1368–1388. doi:10.1017/S0144686X1000139X

4. Zou B. The current situation and active response to China’s aging. China Civil Affairs. 2017;20:42–44.

5. Rico-Uribe LA, Caballero FF, Olaya B, et al. Loneliness, social networks, and health: a cross-sectional study in three countries. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0145264. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145264

6. Cohen-Mansfield J, Hazan H, Lerman Y, et al. Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: a review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28:557–576. doi:10.1017/S1041610215001532

7. Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, et al. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:234–240. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234

8. Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(3):799–812. doi:10.1111/hsc.12311

9. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227–237. doi:10.1177/1745691614568352

10. Wethington E, Pillemer K. Social isolation among older adults. In: Coplan RJ, Bowker J, editors. Handbook of Solitude: Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation, Social Withdrawal, and Being Alone. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014:242–259.

11. Lev EL. Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy: applications to OGCOIogy. Sch Inq Nurs Pract. 1997;11:21–37.

12. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol Rev. 1997;84:191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

13. Lindstrom M, Merlo J, Ostergren P. Individual and neighbourhood determinants of social participation and social capital: a multilevel analysis of the city of Malmo, Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1779–1791. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00147-2

14. Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Relationships between frailty, neighborhood security, social cohesion and sense of belonging among community-dwelling older people. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13(3):759–763. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00967.x

15. Tadaka E, Kono A, Ito E, et al. Development of a community’s self-efficacy scale for preventing social isolation among community-dwelling older people (Mimamori Scale). BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1198. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3857-4

16. Zhao HW, Zhang XL, Liu XC, et al. Validation of the Chinese version of joint protection self-efficacy scale in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheum. 2019;38:2119–2127. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04510-8

17. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: theBarthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65.

18. Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, DiMatteo MR, Reuben DB. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:889–894. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02725.x

19. Zhao HW, Luo W, Maly RC, et al. Validation of the Chinese version 10-item perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions scale in patients with osteoarthritis. Patient Prefer Adher. 2016;10:2189–2195. doi:10.2147/PPA.S110883

20. Resnick B, Palmer MH, Jenkins LS, et al. Path analysis of efficacy expectations and exercise behavior in older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(6):1309–1315. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01463.x

21. Lee LL, Perng SJ, Ho CC, et al. A preliminary reliability and validity study of the Chinese version of the self-efficacy for exercise scale for older adults. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(2):230–238. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.09.003

22. Blumenthal JA, Burg MM, Barefoot J, et al. Social support. Type A behavior, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 1987;49(4):331–340. doi:10.1097/00006842-198707000-00002

23. Qianjin J. Perceived social support scale. Chin J Behav Med. 2001;10(10):41–43.

24. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

25. Joreskog KG, Sörbom D, Du Toit S, et al. LISREL 8: New Statistical Features. Lincolnwood: Scientific software international; 2001.

26. Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1993:136–162.

27. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

28. Cronbach LJ. Co-efficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555

29. Crotina JM. What is co-efficient alpha? A examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78:98–104. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

30. Lohr KN. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. doi:10.1023/A:1015291021312

31. McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:30–46. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30

32. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. doi:10.2307/2529310

33. Verduijn M, Peek N, Rosseel PMJ, et al. Prognostic Bayesian networks I: rationale, learning procedure, and clinical use. J Biomed Inform. 2007;40(6):609–618. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2007.07.003

34. Zhao HW, Dong Z, Xie F, et al. Cross-cultural validation of the educational needs assessment tool into Chinese for use in severe knee osteoarthritis. Patient Perfe Adher. 2018;12:695–705.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.