Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 12

Vaginismus and pregnancy: epidemiological profile and management difficulties

Authors Achour R , Koch M, Zgueb Y , Ouali U, Ben Hmid R

Received 9 September 2018

Accepted for publication 5 February 2019

Published 12 March 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 137—143

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S186950

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Radhouane Achour,1 Marianne Koch,2 Yosra Zgueb,3 Uta Ouali,3 Rim Ben Hmid1

1Emergency Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Maternity and Neonatology Center of Tunis, Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, El Manar University of Tunis, Tunis, Tunisia; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical University of Vienna Austria; 3Psychiatry Department, Razi Hospital, Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, El Manar University of Tunis, Tunis, Tunisia

Background: Vaginismus affects up to 1% of the female population and often represents a physical manifestation of an underlying psychological problem. Our objective was to investigate the psychosomatic impact of vaginismus in pregnant women and evaluate the quality of their therapeutic care in Tunisia.

Methods: We included pregnant patients with vaginismus who presented at our obstetric emergency department between October 2016 and March 2017. All patients were interviewed by one expert psychiatrist and gynecologist using a standardized questionnaire. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to determine anxiety and depression levels. Patients were prospectively followed until their postpartum period and were interviewed by the same experts after delivery. Sixteen weeks after hospital discharge, we contacted all patients via phone. All the information was simultaneously recorded in written form.

Results: Twenty pregnant patients with vaginismus were included (85% primary, 15% secondary). Most women described a conservative family background (70%) in which they received little or no sexual education (60%). All women described a feeling of anxiety and anger immediately before sexual intercourse and 40% have never sought medical consultation regarding their vaginismus before. Only 50% reported regular follow-up visits during their pregnancy (without vaginal examination), whereas 25% reported irregular follow-up visits with subjectively bad experiences during attempts of vaginal examinations.

Conclusion: Pregnant women with vaginismus are at risk of non-follow-up during their pregnancy due to underlying feelings of shame and experienced lack of understanding by medical staff. Obstetricians should carefully and attentively approach pregnant women with vaginismus in order to ensure adequate medical care during pregnancy.

Keywords: vaginismus, pregnancy, profile, impact

The known

Vaginismus is a condition in which vaginal spasms occur and prevent penetration during sexual intercourse. Vaginismus may result in infertility and may affect a woman’s perception about her femininity, her potential of motherhood, and may also affect the maternal and fetal prognosis.

Vaginismus and pregnancy form a particular situation, which could aggravate the underlying symptoms, especially if medical practitioners ignore the women’s special condition and treat them in an inadequate way.

The new

The majority of patients (65%) conceived spontaneously via incomplete sexual intercourse without penetration (ejaculation exteriorly to the vagina).

Vaginismus, a sexual dysfunction preventing any vaginal penetration, a priori, is a symptom incompatible with pregnancy. However, there are virgin vaginal women who become pregnant and experience great physical and mental suffering.

Pregnant women with vaginismus are at risk of non-follow-up during their pregnancy due to underlying feelings of shame and experienced lack of understanding by medical staff.

The implications are as follows: gynecologist must ask for sexual problem in the course of regular follow-up visit of their patients because vaginismus is still considered as a taboo, and affected women do not easily come forward with their complaint. Obstetricians should carefully and attentively approach pregnant women with vaginismus in order to ensure adequate medical care during pregnancy.

Introduction

The family environment, education, and also religious beliefs directly influence the human being. The path of life is often sinuous and complicated, often filled with doubts, prohibitions, traumatic experiences, and the non-said.

Vaginismus is one of the psychological manifestations that results in somatic behavior. Vaginismus is a condition in which vaginal spasms occur and prevent penetration during sexual intercourse.1,2

Several types of vaginismus have been described. The most frequently described in the literature are primary vaginismus and secondary vaginismus. In the case of primary vaginismus, it is impossible to introduce anything, and at any time, into the vagina. Secondary vaginismus occurs after a normal sex life with vaginal penetration. It is often triggered by a traumatic event in relation to the genital area.1–3

Vaginismus may result in infertility and may affect a woman’s perception about her femininity and her potential of motherhood.3 In some cultures, even the perception of being a “woman” implies the ability of being pregnant and bearing a child. Prevalence of vaginismus is difficult to estimate, as there is insufficient data due to a lack of population-wide studies. Frequency in the general population is estimated at about 1% among women of childbearing age, but accounts for 6%–15% according to sexology consultants.4,5

In Tunisia, we do not have specific data on the prevalence of vaginismus, as it remains a pathology not always declared by the patients, and it accounts for ~10%–15% of the sexology consultations.

Despite a lack of literature and data on vaginismus, one can estimate that it affects a considerable number of women by screening the Internet for forums broaching the issue of vaginismus. Difficulties in estimating its prevalence may therefore result from two reasons. First, the medical differentiation between vaginismus and dyspareunia was effective only by 2005 in the Anglophone world, whereas it has been distinguished in the French literature since 1976.6

Second, since vaginismus is still being considered a taboo, affected women do not easily come forward with their complaint and may tend to avoid consulting a gynecologist. About 19% of women with sexual disorders would consult their gynecologist for this reason, whereas up to 50% of affected women would mention their problem in the course of a regular follow- up visit to their gynecologist.7–9

Despite their condition, women with vaginismus show an increasing desire for having children, and despite the difficulties they have to encounter due to their condition, they aim to become pregnant (assisted or spontaneous). During pregnancy, prenatal care visits often represent the first gynecological consultations in these women.10–12

Vaginismus and pregnancy form a particular situation, which could aggravate the underlying symptoms, especially if medical practitioners ignore the women’s special condition and treat them in an inadequate way.

The aim of our study was to investigate the epidemiological and psychosomatic profile of pregnant patients suffering from vaginismus and the difficulties encountered during pre-, per-, and postpartum.

Materials and methods

This is a prospective study including 20 pregnant females with diagnosed vaginismus. We included these patients at the time of their first presentation at our emergency department at the Center of Maternity and Neonatology of Tunis during the time period between October 2016 and March 2017. The aim of our study was to investigate the social demographic profile of these women, their sexual life (sexuality) prior to conception, their original desire for this pregnancy, the route of conception (spontaneous or assisted) of their current pregnancy, the follow-up during pregnancy, and finally the process of delivery and possible complications resulting from it.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Maternity and Neonatology Center of Tunis (00073/2016), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of enrollment.

Inclusion criteria comprised all pregnant patients (≥18 years of age) with diagnosed vaginismus at the time of their presentation at our emergency department and have given consent to participate in the study.

All included patients were separately interviewed by the same expert psychiatrist and expert gynecologist. All interviews were conducted using a standardized, not validated questionnaire, which had been elaborated prior to the recruitment of patients. In order to determine the patients’ anxiety and depression level, The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a commonly used measure of trait and state anxiety.

The concepts of state and trait anxiety were first introduced by Cattell (1966; Cattell and Scheier, 1961, 1963) and have been elaborated by Spielberger (1966, 1972, 1976, 1979).13

Reasons for presentation at the emergency department included pelvic pain, risk of preterm delivery, and vaginal discharge. We retrieved the following data of included patients: age, origin (rural/urban), social economical situation, educational background (in the family context), level of education, marital status, and their medical history including parity. Regarding their sexual education/sexuality, we asked questions pertaining to the following aspects within a structured interview: to describe their experience during their first sexual intercourse; their personal emotions before any sexual intercourse; the character of their husband/partner; and to describe/classify their vaginismus and their emotions which led them to seek medical advice to solve this problem, or which prevented them to seek medical advice. We furthermore asked about possible psychological repercussions, such as anxiety, on the couple and on their familial environment.

Regarding the current pregnancy, we asked about the mode of conception, if they had undergone follow-up visits during the pregnancy (if yes, how many), which route of delivery they would prefer (cesarean section or vaginal delivery), and whether they would be open/would desire to enroll in a postpartum sex therapy.

In order to determine the patients’ anxiety status, we used the STAI form Y-B, which assesses both trait anxiety as well as state anxiety.

After inclusion of the patients in our study and the first completed interview, we prospectively followed these patients until their postpartum period. The following data were documented: route of delivery (cesarean section vs vaginal birth), reasons for choosing it, and possible complications during or resulting from delivery. During the immediate postpartum period, patients were interviewed about their experience during delivery by the same expert psychiatrist and gynecologist. Postpartum pelvic floor training and sex therapy was recommended to all participants, and contact information/addresses were handed out to them before hospital discharge. Sixteen weeks after hospital discharge, we contacted all patients via phone to retrieve the following information: their emotions and subjective feeling about their vaginismus in comparison to before the delivery; if symptoms of their vaginismus had changed after delivery; whether or not they had started postpartum pelvic floor training or if they are planning to enroll in it; whether or not they had seen a sexologist or were planning to see one in the future; and reasons for refusing to consult a sexologist.

All information was retrieved initially during the personal interview and secondarily during the interview by phone in the postpartum period after hospital discharge. Descriptive calculations were performed using Excel.

Results

During the study time period, we were able to recruit 20 pregnant patients with vaginismus out of a total of 540 patients who presented at the emergency department (3.7%). Primary vaginismus was identified in 85% of these women, whereas in the remaining 15% it was secondary vaginismus. The mean age of included patients was 25.6 years (min 22, max 34 years).

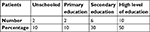

The majority of included patients were primiparous (n=18), whereas two patients were secundiparous. Among included patients, 60% originated from urban areas, whereas 30% originated from rural areas. Socioeconomic status was considered average in 90% of cases. Most included women showed a high level of education (Table 1).

| Table 1 Level of education |

All women were married since an average of 10.6 months. Among our population, most women described a conservative family background (70%) in which they received little or no sexual education (60%). Fifty percent of women reported being unaware of their body and their sexuality. Three women reported a history of sexual abuse and rape. Further two women reported to have undergone “tasfih” in their adolescence, a ritual in which an older female relative performs a ritual on the girl which would guarantee her virginity until marriage.

This ancient ritual (almost now disappeared from our society) mainly consists of incisions at the knees with ritual words.

All women reported pain at their first intercourse. Intercourse is described as being incomplete (inability to reach an orgasm) in 90%, whereas the remaining 10% declared being able to reach an orgasm through manual stimulation of erogenous areas.

Attempts of penetration or partial penetration during sexual intercourse were reported by 30% of women. When questioned about their emotions, all women described a feeling of anxiety and anger immediately before sexual intercourse and 70% also described feeling sad. Only 25% of women reported desire or pleasure before or during intercourse (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Emotions before sexual intercourse according to the number of patients. |

Most women described their partner as being calm, gentle, and understanding (60%), whereas in two cases they were described as being aggressive. Two women furthermore reported premature ejaculation of their partners. Within our study population, 40% of women had never sought medical consultation regarding their vaginismus before. The remaining 60% reported having consulted their gynecologist or a psychiatrist, but none had consulted a sexologist. All women underwent a routine gynecologic examination at the time of their presentation at the department of emergency. In none of the women, any physical cause could be identified for their vaginismus.

The impact on the couple’s relation was described as perturbation of their daily life as a couple, perturbation of their sexual life, reduction of sexual desire, and increase of conjugal conflicts (Figure 2).

| Figure 2 The impact of the problem on the life of the couple. |

In the Tunisian society, it is common that the parents of a couple would influence their lives, and the influence would be even more if there appears a problem such as vaginismus. As a result, women reported a feeling of guilt (15%), of anger (20%), of shame (10%), and a reduction of their self-esteem when not being able to fulfill their parents’ expectations (5%). Half of the patients did not report any influence by their parents, which was, however, in all cases due to their parents’ ignorance.

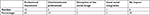

In 40%–60% of patients, their vaginismus had an impact on their socio-professional life, resulting in a retreat of their professional activities and social life (Table 2).

| Table 2 Distribution of patients according to socio-occupational impact |

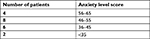

Anxiety level of patients was measured using the STAI questionnaire Y-A. Only two patients showed a very little or no level of anxiety (score below 35) (Table 3). We identified those patients who had been married since 18–24 months as being most likely to show a high level of anxiety.

| Table 3 Level of anxiety |

The majority of patients (65%) conceived spontaneously via incomplete sexual intercourse without penetration (ejaculation exterior to the vagina), whereas 25% underwent artificial insemination and 10% underwent assisted medical reproduction due to reduced female fertility.

Half of the patients reported regular follow-up visits to their gynecologist during their current pregnancy, however, without vaginal examination. Twenty-five percent reported irregular follow-up visits (an average of 1–2 prenatal visits) with subjectively bad experiences during attempts of vaginal examinations. The remaining 25% had never consulted a medical doctor during the current pregnancy.

Determining the mode of delivery troubled all of the patients and in 75% of cases, cesarean section was chosen due to their vaginismus. The remaining 25% delivered vaginally.

The delivery was generally experienced as a challenge, especially considering the reactions of mid-wives and obstetricians. Seven women reported inappropriate commentaries by medical staff, such as “You are not taking any effort - you were able to make the baby, so now you have to deliver it” or “Your poor husband, he won’t find any pleasure with you”.

None of the women underwent postpartal pelvic floor training even though it was recommended to them.

After vaginal delivery, 75% of women considered their problem solved after the baby had passed the birth canal in a way that the vaginal delivery could have cured their vaginismus. However, in four of these patients, an aggravation of their symptoms was reported after vaginal delivery.

Only two patients started seeing a sexologist for a maximum of two consultations during their pregnancy.

During our study, all postpartal women were directed to a sexologist for follow-up on their vaginism; however, none of them accepted the offer. We identified different reasons for their denial: they were not interested in the resolution of their vaginismus (20%), they were primarily interested in motherhood and quality of their sexual life is of inferior importance to them (60%), and they felt misunderstood by medical professionals during their pregnancy and told themselves that nobody could truly understand their problem (70%).

Discussion

Vaginismus prevalence is difficult to appreciate precisely, but the majority of authors place it between 1% and 2%.4 Since it still represents a taboo, the majority of affected women do not consult their gynecologist for this reason. In previous literature, the percentage of women with sexual disorder who would consult a gynecologist for this problem was described as 19%–50%.5,9,14 In our own study population, however, 60% of women with vaginismus reported previously having consulted a medical doctor due to this condition. This may indicate a progress within the Tunisian society, which makes it more acceptable for women to talk about sexual disorders. On the other hand, adequate professional care may still be insufficient, as only few gynecologists would be specialized in sexology.

Among the reasons for not consulting a gynecologist for their vaginismus are subjective perceptions, such as “these sexual problems….are normal by age”, “…are not important”, “…do not represent a medical condition which may be treated”.7,11 Furthermore, about 22% of the affected women reported feeling too intimidated to talk about their problem with a gynecologist, 17% believed that their gynecologist may not be able to help them in anyway, and 12% would not have come up with the idea to present their problem to a medical professional at all. In one previous study,15,16 40% of affected women believed that the medical professional they visit should initiate the topic of sexuality during consultation, whereas about only 8% reported to actually having been interrogated on this topic by their health care provider.8–11

Many studies have reported that affected women would feel confident filling in a questionnaire about their sexuality.8,17,18

All women in our study, who had never consulted a health care provider for their vaginismus (40%), declared that they felt too ashamed and intimidated to bring up the topic on their own. Half of these women, however, indicated that they would have been open to discuss this topic if their gynecologist would have directly brought up this issue.

Literature has described the desire to become pregnant as the primary reason to seek medical care.19–22 In our study, desire for pregnancy was the reason to consult a medical doctor in 60% of the cases.

Often, they are thereafter confronted with lack of understanding by their gynecologist, as one pregnant woman reported: “They were surprised that I was able to become pregnant, suffering from vaginismus, and they did not seem to understand my condition”.

Pregnancy and resulting neonatal follow-up visits represent an opportunity for health care providers to identify women with vaginismus. The majority of affected women, however, had avoided neonatal follow-up visits, as they feared a lack of understanding by their gynecologist when bringing up their suffering. They are often confronted by medical health care staff who are not trained in sexology and hence might not understand their problem, suggesting that “a pregnant woman must have had sexual intercourse, otherwise she would not be pregnant, so a vaginal examination cannot be unbearable for them” (the sayings of the resident in gynecology). Women suffering from vaginismus have described anxiety and insomnia before their gynecological consultation, as well as tachycardia and increased transpiration.4,23

Half of our interviewed patients never had a vaginal examination or transvaginal ultrasound before their consultation at our emergency department. Prenatal care visits offer an opportunity to screen for women with vaginismus and to subsequently offer them guidance in a multidisciplinary setting. In these women, more than in others, establishing a safe environment in which they can feel secure is essential to guarantee adequate medical care.

Psychological preparation for giving birth in these women with vaginismus was unsatisfying in our medical care center, with medical health care staff being insufficiently aware of their special needs. Birthing preparation together with seeing pregnant women who are not suffering from vaginismus may increase the affected womens’ anxiety and their feeling of “not being normal”. It may be helpful to provide them separate groups with specialized medical staff to guarantee a safe environment. Additional care may be offered to them, such as body feedback, relaxation techniques, sophrology, or acupuncture.10,12,24

Vaginal delivery in women with vaginismus is possible but requires sensitive medical staff, and frequency of vaginal examinations during delivery should be reduced to the absolute minimum, which is necessary to guarantee a safe conduct.3,10,12

One previous study identified a significantly higher number of cases involving induction of labor in women with vaginismus compared to women without (37% vs 27%), and a higher number of forceps extractions (9% vs 3%) and cesarean sections (39% vs 15%). There was, however, no statistical difference in neonatal Apgar score or perinatal mortality.10 This may be explained by impossibilities to perform an adequate follow-up during vaginal delivery in women with vaginismus which consequently results in a higher number of operative deliveries. This was confirmed in our study, in which the majority of women (75%) delivered by cesarean section.

Follow- up during the postpartum period may be equally important as identifying and adequately treating women with vaginismus during pregnancy and delivery. In the course of our study, all women were referred to a sexologist after delivery; however, none of the women accepted the offer. The vast majority reported the reason for this being a perceived misunderstanding by medical health care providers and a firm conviction that nobody could truly help them.

This underlines the necessity to provide these women with adequate medical care by trained medical staff much earlier during their prenatal visits during pregnancy.

Conclusion

Vaginism is a pathology that remains highly underdiagnosed, especially in our sociocultural context. The consequences of this pathology affect several psychic, physical, and also relational domains.

The diagnosis is often made during a pregnancy request or during a pregnancy where the woman is obliged to consult a gynecologist after a long period of eviction. Obstetricians should carefully and attentively approach pregnant women with vaginismus in order to ensure adequate medical care during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Further studies across different cultures should be carried out with the aim of establishing a standardized management program and reducing the negative impact of this pathology on women.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Binik YM. The DSM diagnostic criteria for vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(2):278–291. | ||

Lahaie MA, Amsel R, Khalifé S, Boyer S, Faaborg-Andersen M, Binik YM. Can fear, pain, and muscle tension discriminate Vaginismus from Dyspareunia/Provoked Vestibulodynia? Implications for the new DSM-5 diagnosis of Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(6):1537–1550. | ||

Möller L, Josefsson A, Bladh M, Lilliecreutz C, Sydsjö G. Reproduction and mode of delivery in women with vaginismus or localised provoked vestibulodynia: a Swedish register-based study. BJOG. 2015;122(3):329–334. | ||

Collier F, Cour F. En pratique, comment faire devant une femme exprimant une plainte sexuelle? [How to manage a woman with a sexual complaint in clinical practice?] Prog Urol. 2013;23:612–620. | ||

Simons JS, Carey MP. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions: results from a decade of research. Arch Sex Behav. 2001;30(2):177–219. | ||

Cryle P. Vaginismus: a Franco-American story. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2012;67(1):71–93. | ||

Muammar T, McWalter P, Alkhenizan A, Shoukri M, Gabr A, Bin AA. Management of vaginal penetration phobia in Arab women: a retrospective study. Ann Saudi Med. 2015;35(2):120–126. | ||

Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Cohen D, Amsel R. Vaginal spasm, pain, and behavior: an empirical investigation of the diagnosis of vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33(1):5–17. | ||

Bokaie M, Khalesi ZB, Yasini-Ardekani SM. Diagnosis and treatment of unconsummated marriage in an Iranian couple. Afr Health Sci. 2017;17(3):632–636. | ||

Goldsmith T, Levy A, Sheiner E, Goldsmith T, Levy A, Sheiner E. Vaginismus as an independent risk factor for cesarean delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22(10):863–866. | ||

Hope ME, Farmer L, Mcallister KF, Cumming GP, Mairi EH, Laura F. Vaginismus in peri- and postmenopausal women: a pragmatic approach for general practitioners and gynaecologists. Menopause Int. 2010;16(2):68–73. | ||

Rosenbaum TY, Padoa A. Managing pregnancy and delivery in women with sexual pain disorders. J Sex Med. 2012;9(7):1726–1735. | ||

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. | ||

Bakhtiari A, Basirat Z, Nasiri-Amiri F. Sexual dysfunction in women undergoing fertility treatment in Iran: prevalence and associated risk factors. J Reprod Infertil. 2016;17(1):26–33. | ||

Binik YM, Yitzchak MB. Will vaginismus remain a “lifelong” baby? Response to Reissing et al. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(7):1215–1217. | ||

Cherner RA, Reissing ED, Elke D. A comparative study of sexual function, behavior, and cognitions of women with lifelong vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(8):1605–1614. | ||

Ozdemir O, Simsek F, Ozkardeş S, Incesu C, Karakoç B. The unconsummated marriage: its frequency and clinical characteristics in a sexual dysfunction clinic. J Sex Marital Ther. 2008;34(3):268–279. | ||

Karrouri R, Rabie K. Mariage non consommé et vaginisme: à propos de trois cas Clinique [Non-consummation of marriage and vaginismus: about three clinical cases]. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:60. French. | ||

Michetti PM, Silvaggi M, Fabrizi A, Tartaglia N, Rossi R, Simonelli C. Unconsummated marriage: can it still be considered a consequence of vaginismus? Int J Impot Res. 2014;26(1):28–30. | ||

Simonelli C, Eleuteri S, Petruccelli F, Rossi R. Female sexual pain disorders: dyspareunia and vaginismus. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(6):406–412. | ||

Bydlowski M. Psychic factors in female unexplained infertility. Gynécol Obstét Fertil. 2003;31:246–251. | ||

Salama S, Boitrelle F. Gauquelin A, et al. Sexuality and infertility. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2012;40:780–783. | ||

Colson MH, Lemaire A, Pinton P, Hamidi K, Klein P. Sexual behaviors and mental perception, satisfaction and expectations of sex life in men and women in France. J Sex Med. 2006;3(1):121–131. | ||

Jindal UN, Jindal S. Use by gynecologists of a modified sensate focus technique to treat vaginismus causing infertility. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2393–2395. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.