Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 9

Using drawings to explore patients’ perceptions of their illness: a scoping review

Authors Cheung MMY , Saini B , Smith L

Received 21 August 2016

Accepted for publication 15 October 2016

Published 24 November 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 631—646

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S120300

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Melissa Mei Yin Cheung, Bandana Saini, Lorraine Smith

Faculty of Pharmacy, The University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW, Australia

Background: An emerging approach for investigating patient perspectives of their illness is the use of drawings.

Objective: This scoping review consolidates findings from current literature regarding the use of drawings to explore patients’ perceptions and experiences of their illness and treatment.

Methods: Electronic databases (Medline, PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, Cinahl, Art Index and Scopus) and reference lists were searched to identify published English language studies using participant-generated drawings to explore adults’ perceptions and experiences of their illness and treatment. Using the scoping methodological framework, data were analyzed with respect to each study’s design, key findings and implications.

Results: Thirty-two studies were identified and these reflected diversities in both health conditions and methods of data collection and analysis. Participants’ drawings revealed new, insightful knowledge about patients’ perceptions, beliefs and experiences of their condition and were associated with clinical and psychological markers of health. Drawing was a powerful adjunct to traditional data collection approaches, and demonstrated potential benefits for participants. This review provides detailed insights and guidance on the use of drawings in research and clinical practice.

Conclusion: Drawing is a novel and potentially valuable technique for exploring patients’ perceptions and experiences about their illness and treatment. Advancing the methodology and applicability of drawings in this area will assist in the future development of this technique, with benefits for the patient, researcher and health care professional alike.

Keywords: scoping review, drawing, illness perceptions, patient experience

Background

Research into ‘arts and health’ showcases various innovative approaches to research, education and therapy.1–3 According to the Australian National Arts in Health Framework, arts and health refers broadly to the practice of applying arts-based initiatives to health problems and health promoting settings.4 It involves all art forms, such as drawings, photographs, drama and music, and may be focused at any point in the health care continuum. The arts offer participatory possibilities to create (knowledge production) as well as to view (knowledge translation).1,5 From a systems perspective, the use of arts in health has a positive impact on population health.6 From an individual patient perspective, creating art provides an opportunity to reflect on personal experiences and acquire new insights about their own thoughts and emotions, painting a detailed picture of their beliefs about their illness and treatment.1,7 Deepened understanding of the self can lead to more active involvement in illness management and self-care.8 Likewise, increased insight into patients’ health beliefs and personal experiences will provide health care professionals with a broader understanding of health behavior. This has the potential to guide the provision of care and self-management support that better meets the needs of the individual.9

It is important to investigate patients’ perceptions about their illness and treatment, as these beliefs can influence patient behavior and outcomes.9,10 The use of quantitative methods to elicit patient perceptions or beliefs about their health and treatment has benefits of psychometric validity, reliability and convenience.11,12 However, these methods are rather restrictive in exploring perspectives and experiences which often require deeper discussion. Qualitative approaches such as interviews can address this gap, although they can overlook issues which are largely subconscious and difficult to verbalize. Within participatory forms of art in health, the use of metaphors and expression can create a safety net for participants to openly express difficult issues. Cognitively, production of art activates different areas of the brain compared with verbal communication.13 Also, practically, art can be useful when people may have difficulty conveying their thoughts verbally due to functional or language barriers. Utilizing such techniques can allow inclusion of marginalized and diverse groups of people in health related discussions.6 Examples of such initiatives include employing photovoice to explore the experiences of patients with myotonic dystrophy. In this study, participants used visual images to depict barriers and facilitators to living successfully with the condition.14 Another example is the display of indigenous artwork to encourage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to be screened for breast cancer.15

A growing approach for investigating patient perceptions and experiences of illness is the use of drawings. Conventionally drawings represent a hand-drawn sketch that provides a visible form to a thought, concept or idea. Children often use drawing as a means of communicating thoughts visually and research in this area takes on developmental and clinical perspectives.16 Adults have also been engaged in this form of art, as it can offer individuals alternate ways of looking at phenomena and reveal dimensions of meaning not previously considered.17 This method of active participatory engagement can help shed deeper insight into how patients view and respond to illness.17

Reviews of arts-based methods in health are positive about the usefulness of employing various art forms to engage and enrich health determinants.1,5 However, issues with inconsistent methodology and theoretical frameworks point to the need for ongoing research in this field. Specifically, there is yet to be a consolidation of published studies investigating drawing as a participatory research and clinical tool. This is distinguished from the use of pictures and drawings to communicate health research findings and to explain health instructions to patients.18,19 Synthesizing the extent, range and nature of research in this area will generate new understandings of the existing empirical work to guide future inquiry. Therefore, the objective of the current review was to conduct an examination of the use of drawings to explore patients’ perceptions and experiences of their illness and treatment.

Methods

Review type

Scoping reviews represent an increasingly popular approach to reviewing and collating health research evidence.20,21 This review was guided by the recommendations published in Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework.22 Different from systematic reviews, scoping reviews tend to address broader topics with a focus on summarizing and synthesizing data from a wide range of disciplines and methodologies.22 The intention is to obtain an overall picture of an issue or area of research, rather than to assess the quality of evidence to determine the generalizability or robustness of findings. A systematic review would be particularly challenging with the area of patients’ drawings in health, given that most of the work around drawings is exploratory and the study designs often do not involve randomization or clinical trials. As an essential first step in rigorous and systematic research, the scoping process provides valuable insights into how drawings have been used so far, the strengths and weaknesses of this technique and identifies research gaps to guide future studies.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched: Medline, PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, Cinahl, Art Index and Scopus. There was no restriction set on publication recentness. In addition to databases, the reference lists of the articles included in this review were hand-searched to identify articles that were not uncovered in the database searches.

Search strategies were formulated for individual databases using the following keywords: ‘illness perceptions’ or ‘illness representations’ or ‘attitude to health’ or ‘health beliefs’ or ‘beliefs about medicines’ or ‘beliefs about treatment’ or ‘patient experience’ AND ‘drawings’ or ‘art therapy’ or ‘visual arts’ or ‘visual representations’. The search strategy for Medline is provided (Supplementary material). This was adapted according to the indexing systems of the other databases searched.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were limited to those that 1) specified the use of participant-generated drawings in the method, 2) explored participants’ perceptions and experiences of their illness and/or treatment, 3) involved participants aged 18 years or over, and 4) were written in English.

Study selection and analysis

Titles and abstracts were reviewed and the full texts of all potential articles meeting the inclusion criteria were obtained for additional review. Three authors were involved in study selection, differences in opinion were discussed and a consensus was reached. Data from included papers were charted and analyzed for the following: author(s), year of publication, country, aims of the study, health condition of participants, sample size, theoretical frameworks, methods used in conjunction to drawing, study design, data analysis and key findings.

Results

Descriptive findings

The database searches generated 2,563 possible articles (Figure 1). Following elimination of non-English language studies, duplicates and studies not meeting the inclusion criteria, 26 studies remained. Six additional studies were identified by searching the reference lists of the included articles, resulting in a total of 32 studies which were included in this review.

| Figure 1 Results of search strategy. |

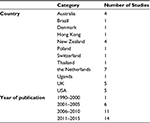

A number of studies were conducted in the Netherlands and most were published in the last decade (Table 1). The health topics explored in the studies were diverse and included cancer (n=6), cardiovascular disease (n=4), gynecology (n=4), immunology (n=4), chronic pain (n=3), endocrinology (n=3), mental health (n=2), respiratory disease (n=1) and others (n=5). Key characteristics and findings from these articles are summarized in Table 2.

| Table 1 Background of studies included in this review |

| Table 2 Characteristics and findings of the studies included in this review |

Analytic findings

Theoretical frameworks

Seventeen studies utilized theoretical frameworks, including: the common-sense model of self-regulation,23–30 phenomenology,31–34 phenomenography,35,36 a feminist framework,37–39the illness-meaning model,40–42 the social representation theory,43,44 and the transition theory.45,46 Theoretical frameworks underpinning the studies were not reported in the remaining fifteen publications.47–61

Study designs

In all studies, the data collected from the analyses of participant-created drawings was supplemented with either interviews (n=18), self-reported questionnaires (n=12), or both (n=2). Some studies where drawing was supplemented by questionnaires asked participants to provide a brief written description of their image. For studies where drawing was used together with interviews, drawings were often made after a one-on-one interview with a researcher and a discussion about the image followed. Two studies specified that participants were alone when completing the drawing task in interviews.31,33 Conversely, in another study drawings were created in a group setting with other participants.32

Instructions to participants for creating the drawing were either verbally communicated or provided in a written form. Participants were asked to draw a variety of images, such as specific organs, how they saw their condition or body, and their experiences and feelings. Many researchers emphasized the importance of informing participants that the activity was not an assessment of artistic skill, that there were no correct or incorrect ways of drawing images, and that the key focus in the exercise was indeed the participants’ views.

Methods of data analysis varied between studies and the majority (n=20) incorporated participants’ own interpretation and description of their drawings. The most commonly used methods of data analysis were thematic analysis only (n=14), and a combination of content analysis of the drawings with statistical analysis of questionnaire data collected adjunctive to the drawing (n=13). Participants from two studies received a copy of their interview transcript for comment and approval about accuracy and relevance.37,40 To analyze the drawings, eleven studies used NIH Image-J software (which calculates pen stroke intensity and drawing dimensions and area), five studies drew on Guillemin’s adaptation51 of Rose’s critical visual methodology framework62 and one study applied the interpretative phenomenological analysis methodology.63

Key findings

Characteristics of participants’ drawings were associated with clinical and psychological markers of health status. Drawings of damage to the heart after myocardial infarction predicted recovery better than medical indicators of damage.49 Increases in size of drawings of the heart at follow-up after myocardial infarction were related to higher cardiac anxiety, activity restriction and health care use.47 Similar results were observed in participants with heart failure where larger sized drawings of the heart were associated with greater levels of heart-specific anxiety.59 Drawing size also represented the clinical severity of heart failure59 and Cushing’s syndrome.60 While there were no clear associations between drawings and illness perceptions or quality of life in patients with long-term remission of Cushing’s syndrome,60 strong correlations between larger sized drawings and impaired quality of life were identified in patients with long-term remission of acromegaly.28 Also, quality of life was negatively associated with the illustration of emotions for patients with vestibular schwannoma29 and was related to images of recovery for participants who experienced emergency embolization in postpartum hemorrhage.61 Increased pain ratings and emotional distress were reflected in drawings with an external force to the head drawn by participants with persistent headaches.48

Drawings added to current knowledge about patient perceptions and experiences of illness and treatment. In the artwork created by people with spinal cord injury, the range of ways participants depicted their feelings about the lasting social consequences and concerns about their body image, advanced knowledge of how people understand their injury and its impact on their lives.50 In the case of chronic vaginal thrush, analyses of patient drawings yielded a new theme regarding patient experiences of thrush that has not been reported in previous literature.37 Drawings of the kidney by people with systemic lupus erythematosus provided additional information about their perceptions of treatment effectiveness, kidney function and their understanding of the condition.24 This was also reflected in several other illnesses, where analyses of drawings created by participants highlighted the unique ways in which the illnesses or conditions were comprehended and experienced, for example, heart disease,52 menopause,51 postnatal depression53 and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.40,41 This additional insight emerging through an analysis of patient-created drawings was also observed in studies involving patients with lung cancer,25 severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,57 and Ebola infection.35

In addition to the experience of illness, affects such as feelings toward and views about their illness were better elicited using the method of participants’ visual representations. Participants described stronger emotional reactions when discussing their drawings of osteoporosis that were not reported in their interviews.23 This aspect was mirrored in participants with long-term remission of Cushing’s syndrome60 and acromegaly,28 where additional information about their illness perceptions was revealed with drawings as compared to questionnaires. Also, drawings added a further element to the assessment of psychological status in patients with heart failure.59 Artistic representations illuminated elusive and less accessible areas, revealing deeply personal accounts of the experience of chronic pain26,33 and the various dimensions of patients’ views of systemic lupus erythematosus.58

In a number of studies, drawings resulted in ‘richer’ data collection, offering advantages over other methods. For example, researchers found that inclusion of a drawing activity generated more discussion about the personal impact of osteoporosis as compared to the participants’ interviews.23 This was similarly observed in participants with postnatal depression; some participants spoke briefly about their illness during their interviews, yet when they represented their feelings through drawings, deeper insight into their ways of understanding their condition was illuminated.53 It was also reported that drawings were a good initiator to encourage participants to open up about and share their illness experience.58 The drawing method enhanced elicitation of narratives about sensitive topics, such as chronic vaginal thrush,37 and discussion about the clinical presentation of illness, for example by asking patients to draw the development of their melanoma retrospectively.27

The usefulness of drawing as an adjunct to other methods of data collection rather than as a standalone technique was put forward by several researchers. By adding elements which may not be accessible using interviews,52 drawings were a powerful adjunct to word-based means.53 It enabled the comparison of data obtained from different modes.51 For example, characteristics of participants’ drawings were associated with scores from the Illness Perception Questionnaire in some studies,24,28,48 but not others.60 Drawings provided clarification regarding information that has been provided in another form54 and enabled credibility to be added to themes identified using other methods.41 By combining drawing with interviews and questionnaires, the broadest range of patients’ perceptions is likely to be captured.24,27

A number of studies reported on participants’ evaluation of the process of drawing. Despite being informed about and consenting to a drawing activity, the request to draw came as a surprise for some participants.24,51 They showed initial hesitation24,37,51 and completed their drawing after some reflection and consideration.24,51 Some participants proffered apologies for their drawing, believing their drawings may not be good enough,37 and at times, others drew with intent and force.51 In one study, a participant conveyed that drawing was useful, related very personally, clarified their experience and enabled expression and reflection.32 A participant in another study thought that drawing was a moving experience and a new form of expression which told them much about themselves that they were not consciously aware of prior.40 Likewise, other participants found the process of drawing to be beyond the verbal, offering therapeutic benefits and an opportunity to access deeper levels of emotions.33,37

Discussion

This is the first review of the current literature on how drawings have been used to explore patients’ perceptions and experiences of their illness and treatment. This scoping review has identified that drawings have added new and insightful knowledge about patients’ perceptions, beliefs and experiences of their condition and are a potentially valuable technique for patients, researchers and health care professionals. Drawings were associated with indicators of health status and improved current understanding of the patient’s perspective. Patients’ visual representations revealed deeply personal and emotional accounts of their illness experience and demonstrated potential for benefits for patients. By facilitating richer data collection, drawing was a powerful adjunct to traditional approaches. This review also provides a detailed synthesis of the study designs, offering valuable guidance and considerations to inform future applications of the drawing technique in health.

The findings of the review indicate that the method of data collection may have bearing on the outcomes. There are several variables which are important to consider, for example, using multiple data collection methods, offering personal space and time to complete the drawing, and the range of art materials provided. Accompanying the drawing activity with an in-person interview or a postal questionnaire allowed a comparative analysis of the data collected by different methods. In the reviewed studies (Table 2), when face-to-face interviews supplemented data from drawings, this highlighted how the interview provided an opportunity for researchers to develop rapport with participants and to initiate further discussions. In contrast, drawings in the postal questionnaires completed away from the researchers negated the chance for investigations to explore more deeply. Asking participants to draw at home55 or alone31,33 can reduce potential external pressure. Whilst drawing in a group setting32 can have implications concerning privacy and social desirability, this method can facilitate discussion and the sharing of experiences through interaction with others.64,65

The way in which participants were encouraged to draw could have influenced the findings obtained. As shown by Michie and Abraham, the different elements of a study’s design can affect participant behavior.66 Providing participants with a range of drawing materials enables more options for expression, demonstrating the wide range of expressive styles that drawing can offer to people. Specifying the object(s) to draw can target a particular topic of research interest, while a general drawing request can be open to interpretation. The latter allows freedom of expression but can lead to more uncertainty amongst participants. Though, it was observed that reassurance that the activity was not an assessment of drawing skill was frequently sufficient to overcome participants’ initial hesitation to draw.

In order for the use of drawings in health to be translated into everyday practice, their effectiveness requires an evidence-base. A balance is needed to achieve an adoption of protocols which do not constrain creativity and qualitative inquiry. Rather than over-prescription, consideration about having a minimum standard for patient instructional specificity, detail and intent is needed. In addition to procedures, analyses of the actual image also need to be taken into account.

The reviewed studies differed considerably in regards to analyses of participants’ drawings, with some seeking participants’ interpretation and others using researcher-derived interpretations. Seeking participants’ interpretation of their own drawing is invaluable as their visual product is highly subjective and can be easily misunderstood from a third perspective. Great care needs to be taken if researchers are to interpret participants’ drawings without their input and authors have demonstrated that it is imperative to acknowledge this as a study limitation. A proportion of studies were unclear regarding how or who interpreted the drawings.24,43,47,49,56,58,61 It would be useful to specify the number and background of raters. Five studies reported the kappa value for inter-observer reliability.25,28,57,59,60 However, kappa statistics can only be useful if the raters are looking at objective elements such as size and quantity of the contents in the drawing. Interpretation of meaning, for example the perception of limitations and difficulties suggested in the drawings, remain as interpretations by the raters and do not infer authenticity.

The use of theoretical frameworks assisted in the design of the studies’ methods by providing structure and guidance to the collection and analysis of data. However, a number of studies did not utilize particular theories to aid the exploration and development of the drawing technique in health.47–61 The theoretical approaches used aligned with the research’s objectives. Studies which aimed to explore participants’ perceptions of their illness drew on the common-sense model of self-regulation, which proposes factors that may influence patient interpretations and responses.30 While phenomenology34,63 underpinned the studies which sought to explore in-depth the lived experience of the participants. In a number of studies, thematic analysis of the drawings and participants’ descriptions drew on Guillemin’s adaptation51 of Rose’s critical visual methodology framework.62 This framework poses a series of questions regarding the process of image production, the composition of the image, and the relationship between the image and the audience.51 Whilst this is a step forward in enabling a system of comparison between studies, rigorous evaluation of the extent to which this is a valid approach is needed as there is currently a lack of literature critiquing the applicability of this methodology in health research.

Examining which methods or combination of methods are most useful for particular conditions or settings should be considered according to the epistemological perspective and research questions. From the findings in this review, for example, it appears that a qualitative study aiming to explore patients’ experiences of a health condition would benefit from offering participants a range of art materials, not limiting the time and space for drawing and reassuring participants that the focus of the activity is their views and not drawing ability. Additionally, asking participants for their description of their drawing using a semi-structured interview guided by a visual methodology (such as Guillemin’s adaptation51 of Rose’s critical visual methodology framework62) would aid interpretation and analysis, as would using an underpinning theoretical framework appropriate for the phenomena of interest.

The studies in this review were subject to several shortcomings. In some studies with a quantitative component, the authors highlighted that the validity and generalizability of the findings were uncertain as there may have been insufficient power to detect a meaningful association between variables due to restrictions in sample size.24,25,28 However, it is important to recognize that power is not relevant when discussing the associations between quantitative and qualitative components. These associations could be spurious or mediated by various factors which may be difficult to control for, such as the way in which participants are encouraged to draw, or differing image interpretation frameworks. Additionally, sample participants were in majority females, hence the general applicability of drawing as a health tool is unclear across the genders. Future investigations should explore whether drawing can be applied broadly, by incorporating a wider range of social determinants and health conditions.

Application of the drawing technique to explore patients’ perceptions and experiences of their illness would benefit from wider critical debate regarding its value and challenges in order to support the development of appropriate methods for conducting such studies for research, and possibly, its implementation into clinical practice. This will allow for procedures which are rigorous and transparent. A relevant case in point is the development of a methodological framework for scoping studies. The collective work from numerous independent researchers from foundation22 to ongoing critical discourse20,21 demonstrates that such process brings together varied experiences and recommendations to build, clarify and enhance the scoping methodology. However, the reviewed studies offered little evidence of critique of the methods and results that related to drawing, with two exceptions.37,51 It is therefore strongly encouraged that researchers contribute to the discussion that would advance the methodology of drawing in health.

Nevertheless, the findings of this review provide important insights for clinicians. Through the use of drawings, health care professionals could better understand and appreciate individual patients’ perceptions and experiences of illness. Drawings revealed new knowledge about the heterogeneity of patients’ perceptions, beliefs and feelings. Several studies suggested that drawing could be a simple yet universal assessment tool.26,55,58 This is a promising area for future work, as research has identified associations between characteristics of participants’ drawings and clinical and psychological markers of health status in a range of conditions.28,29,48,49,59

Exploring the patient’s subjective view through drawings presents an opportunity to realign misperceptions and idiosyncratic beliefs.28,54,56,60 Drawings can uncover many dimensions of living with disease, especially psychosocial,58 which can provide health care professionals with an indication of how the patient is dealing with their illness. Generating or discovering knowledge about this is difficult without engaging patients themselves in this process.67 As a medium for participatory research, drawings can be used to support knowledge construction through a cooperative process actively involving the individuals who live with the health condition. Also, this creative activity offers patients an open way of expression which can minimize health care professionals’ (and researchers’) imposition of their own views.

The drawing technique can also have potential benefits for patients. By offering a time and space for reflection, patients can access perceptions and emotions which may have been unknown previously. The uncovering of unconscious and subconscious aspects may be distressing, but this knowledge could also help patients better understand themselves and their needs. Not all patients will benefit from or be comfortable with one technique. However, this demonstrates the multiplicity of forms of communication and expression that people utilize, and drawing is offering another way for people, especially those who are visually or creatively-orientated, to voice themselves. Previous research has shown that the use of art as therapy for patients with cancer can be beneficial, especially psychosocially.8,68,69 Despite positive feedback from some participants, most studies did not include participants’ appraisal of the drawing process. This is an important aspect to explore in order to determine the benefits of drawing for participants.

Drawings can provide additional understandings beyond that of patient experiences. For example, they are an innovative way of identifying patient needs and feedback about health care services. Participants with osteoporosis23 and perimenopause45 expressed that they had little understanding about their illness and treatments. Despite the biomedical aspects of osteoporosis, menopause and postnatal depression, participants’ illness and medication beliefs depicted in their drawings either did not match scientific evidence23 or there was an absence of drawings demonstrating medical understanding.51,53 This suggests room for improvement in providing education to patients regarding these conditions. In some of the reviewed studies, participants also gave feedback regarding health care services, pointing to a lack of helpful interaction between patient and practitioner when treating chronic vaginal thrush,37 inadequate treatment for people committed to long-term psychiatric hospitalization,43 and insufficient support in managing stigma after receiving breast cancer treatment.38 Recognizing areas of potential improvement in clinical encounters can advance patient care and help build stronger patient–practitioner relationships.

When patients consult a health care professional, they have preconceived beliefs, attitudes and understanding, as reflected in the common-sense model of self-regulation.9,10,30 These representations can differ vastly from biomedical views.57,70 If there is poor fit between the patient’s schema and the nature of the health care professional’s recommendations, there is a risk that the advice provided does not make sense to the patient.10 As this can affect health behavior and clinical and psychosocial outcomes,71 it is important to explore patients’ perceptions. Leventhal et al72 proposed that verbal statements from patients can describe only some, but not all, of the features of their cognitive and emotional representations. Words provide a limited view of the patient’s experience,72 and this may be where drawings can supplement by “[picturing] where words come short”.31 By consulting patients about their views and feelings regarding their illness and treatment, health care professionals acknowledge that patients are also experts. Shifting to a patient-focused approach can support patients to actively participate in their care and this can in turn improve self-management and health outcomes.73,74

This review was subject to certain limitations. The search strategy used to identify potential studies was limited to specific search terms and databases, and this may have affected the studies identified. Also, unpublished, non-English language and gray literature were not included in this review. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs and the variation in contexts and study populations, a meaningful pooling of data could not be performed.

A strength of this scoping review was the in-depth analysis of the studies in terms of their design, findings and implications for research and clinical practice. These findings provide important guidance for researchers and health care professionals interested in using drawings to gain a deeper understanding of patients’ perceptions and experiences of their illness and treatment. The potential advantages of drawing provide valuable pointers for future research directions. For example, further development of the methodology of drawing as a research technique in health, use of longitudinal study designs to incorporate drawing as an outcome measure, and replication of the studies included in this review in a range of medical conditions could be considered in subsequent studies.

Conclusion

This scoping review calls attention to drawing as a novel way to explore patients’ perceptions and experiences of their illness and treatment. The findings of this review form a basis to justify future research into drawing as a research, diagnostic and therapeutic tool in health, with benefits for the patient, researcher and health care professional alike.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Boydell KM, Gladstone BM, Volpe T, Allemang B, Stasiulis E. The production and dissemination of knowledge: a scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2012;13(1). | ||

Stuckey HL, Nobel J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: a review of current literature. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):254–263. | ||

Harrison B. Seeing health and illness worlds – using visual methodologies in a sociology of health and illness: a methodological review. Sociol Health Illn. 2002;24(6):856–872. | ||

Meeting of Cultural Ministers & Standing Council on Health. National Arts and Health Framework. Australia: Ministry for the Arts; 2014. Available from: https://www.arts.gov.au/national-arts-and-health-framework. Accessed May 12, 2016. | ||

Fraser KD, al Sayah F. Arts-based methods in health research: a systematic review of the literature. Arts Health. 2011;3(2):110–145. | ||

Clift S. Creative arts as a public health resource: moving from practice-based research to evidence-based practice. Perspect Public Health. 2012;132(3):120–127. | ||

Camic PM. Playing in the mud: health psychology, the arts and creative approaches to health care. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(2):287–298. | ||

Wood MJ, Molassiotis A, Payne S. What research evidence is there for the use of art therapy in the management of symptoms in adults with cancer? A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):135–145. | ||

Cameron LD, Leventhal H. The self-regulation of health and illness behavior. London and New York: Routledge; 2003. | ||

Petrie KJ, Weinman J. Patients’ perceptions of their illness: the dynamo of volition in health care. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012;21(1):60–65. | ||

Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Moss-Morris R, Horne R. The illness perception questionnaire: a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychol Health. 1996;11(3):431–445. | ||

Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14(1):1–24. | ||

Bolwerk A, Mack-Andrick J, Lang FR, Dörfler A, Maihöfner C. How art changes your brain: differential effects of visual art production and cognitive art evaluation on functional brain connectivity. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101035. | ||

LaDonna KA, Venance SL. Picturing the experience of living with myotonic dystrophy (DM1): a qualitative exploration using photovoice. J Neurosci Nurs. 2015;47(5):285–295. | ||

Queensland Government. Breastscreen Queensland: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women; 2015. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/breastscreen/aboriginal-tsi-women.asp. Accessed May 12, 2016. | ||

Papandreou M. Communicating and thinking through drawing activity in early childhood. J Res Child Educ. 2014;28(1):85–100. | ||

Theron L, Mitchell C, Smith A, Stuart J. Picturing research: drawing as visual methodology. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers; 2011. | ||

Bartlett R. Visualising dementia activism: using the arts to communicate research findings. Qual Res. 2015;15(6):755–768. | ||

Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, Loscalzo MJ. The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(2):173–190. | ||

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. | ||

Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:48. | ||

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. | ||

Besser SJ, Anderson JE, Weinman J. How do osteoporosis patients perceive their illness and treatment? Implications for clinical practice. Arch Osteoporos. 2012;7:115–124. | ||

Daleboudt GM, Broadbent E, Berger SP, Kaptein AA. Illness perceptions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and proliferative lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2011;20(3):290–298. | ||

Hoogerwerf MA, Ninaber MK, Willems LN, Kaptein AA. “Feelings are facts”: illness perceptions in patients with lung cancer. Respir Med. 2012;106(8):1170–1176. | ||

Phillips J, Ogden J, Copland C. Using drawings of pain-related images to understand the experience of chronic pain: a qualitative study. Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78(7):404–411. | ||

Scott SE, Birt L, Cavers D, Shah N, Campbell C, Walter FM. Patient drawings of their melanoma: a novel approach to understanding symptom perception and appraisal prior to health care. Psychol Health. 2015;30(9):1035–1048. | ||

Tiemensma J, Pereira AM, Romijn JA, Broadbent E, Biermasz NR, Kaptein AA. Persistent negative illness perceptions despite long-term biochemical control of acromegaly: novel application of the drawing test. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(5):583–593. | ||

van Leeuwen BM, Herruer JM, Putter H, van der Mey AG, Kaptein AA. The art of perception: patients drawing their vestibular schwannoma. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(12):2660–2667. | ||

Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S, et al. Illness representations: theoretical foundations. In: Weinman J, Petrie KJ, editors. Perceptions of health and illness: current research and applications. London: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997:19–45. | ||

Hammer K, Hall EO, Mogensen O. Hope pictured in drawings by women newly diagnosed with gynecologic cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(4):E42–50. | ||

Henare D, Hocking C, Symthe L. Chronic pain: gaining understanding through the use of art. Br J Occup Ther. 2003;66(11):511–518. | ||

Kirkham JA, Smith JA, Havsteen-Franklin D. Painting pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of representations of living with chronic pain. Health Psychol. 2015;34(4):398–406. | ||

van Manen M. Researching lived experience. Human science for action-sensitive pedagogy. 2nd ed. Ontario: Althouse Press; 1997. | ||

Locsin RC, Barnard A, Matua AG, Bongomin B. Surviving Ebola: understanding experience through artistic expression. Int Nurs Rev. 2003;50(3):156–166. | ||

Barnard A, McCosker H, Gerber R. Phenomenography: a qualitative research approach for exploring understanding in health care. Qual Health Res. 1999;9(2):212–226. | ||

Morgan M, McInerney F, Rumbold J, Liamputtong P. Drawing the experience of chronic vaginal thrush and complementary and alternative medicine. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2009;12(2):127–146. | ||

Suwankhong D, Liamputtong P. Breast cancer treatment: Experiences of changes and social stigma among Thai women in southern Thailand. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(3):213–220. | ||

Liamputtong P. Researching the vulnerable: a guide to sensitive research methods. London: Sage; 2007. | ||

Salmon PL. Viewing the client’s world through drawings. J Holist Nurs. 1993;11(1):21–41. | ||

Scott A. Illness meanings of AIDS among women with HIV: Merging immunology and life experience. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(4):454–465. | ||

Kleinman A. The illness narratives: suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York: Basic Books; 1988. | ||

Pereira MA, Furegato AR, Pereira A. The lived experience of long-term psychiatric hospitalization of four women in Brazil. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2005;41(3):124–132. | ||

Moscovici S. Social representations: essays in social psychology. New York: New York University Press; 2001. | ||

Marnocha SK, Bergstrom M, Dempsey LF. The lived experience of perimenopause and menopause. Contemp Nurse. 2011;37(2):229–240. | ||

Meleis AI. Transitions theory: middle-range and situation specific theories in nursing research and practice. New York: Spring; 2010. | ||

Broadbent E, Ellis CJ, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Changes in patient drawings of the heart identify slow recovery after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(6):910–913. | ||

Broadbent E, Niederhoffer K, Hague T, Corter A, Reynolds L. Headache sufferers’ drawings reflect distress, disability and illness perceptions. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(5):465–470. | ||

Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Ellis CJ, Ying J, Gamble G. A picture of health - myocardial infarction patients’ drawings of their hearts and subsequent disability: a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(6):583–587. | ||

Cross K, Kabel A, Lysack C. Images of self and spinal cord injury: exploring drawing as a visual method in disability research. Vis Stud. 2006;21(2):183–193. | ||

Guillemin M. Understanding illness: using drawings as a research method. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(2):272–289. | ||

Guillemin M. Embodying heart disease through drawings. Health (London). 2004;8(2):223–239. | ||

Guillemin M, Westall C. Gaining insight into women’s knowing of postnatal depression using drawings. In: Liamputtong P, Rumbold J, editors. Knowing differently: arts-based and collaborative research methods. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2007:121–139. | ||

Harrow A, Wells M, Humphris G, Taylor C, Williams B. “Seeing is believing, and believing is seeing”: an exploration of the meaning and impact of women’s mental images of their breast cancer and their potential origins. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(2):339–346. | ||

Ho RT, Potash JS, Fu W, Wong KP, Chan CL. Changes in breast cancer patients after psychosocial intervention as indicated in drawings. Psychooncology. 2010;19(4):353–360. | ||

Kaptein AA, Zandstra T, Scharloo M, et al. ‘A time bomb ticking in my head’: drawings of inner ears by patients with vestibular schwannoma. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011;36(2):183–184. | ||

Luthy C, Cedraschi C, Pasquina P, Uldry C, Junod-Perron N, Janssens JP. Perception of chronic respiratory impairment in patients’ drawings. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(7):694–700. | ||

Nowicka-Sauer K. Patients’ perspective: lupus in patients’ drawings. Assessing drawing as a diagnostic and therapeutic method. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(9):1523–1525. | ||

Reynolds L, Broadbent E, Ellis CJ, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Patients’ drawings illustrate psychological and functional status in heart failure. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(5):525–532. | ||

Tiemensma J, Daskalakis NP, van der Veen EM, et al. Drawings reflect a new dimension of the psychological impact of long-term remission of Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):3123–3131. | ||

van Stralen G, van Stralen-Ruijten LL, Spaargaren CF, Broadbent E, Kaptein AA, Scherjon SA. Good quality of life after emergency embolisation in postpartum haemorrhage. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;31(4):285–288. | ||

Rose G. Visual methodologies: an introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. London: Sage; 2007. | ||

Smith JA. Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychol Health. 1996;11:261–271. | ||

Acocella I. The focus groups in social research: advantages and disadvantages. Qual Quant. 2012;46(4):1125–1136. | ||

Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J. 2008;204(6):291–295. | ||

Michie S, Abraham C. Interventions to change health behaviours: evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychol Health. 2004;19(1):29–49. | ||

Borg M, Karlsson B, Kim HS, McCormack B. Opening up for many voices in knowledge construction. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2012;13(1). | ||

Nainis N, Paice JA, Ratner J, Wirth JH, Lai J, Shott S. Relieving symptoms in cancer: innovative use of art therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(2):162–169. | ||

Forzoni S, Perez M, Martignetti A, Crispino S. Art therapy with cancer patients during chemotherapy sessions: an analysis of the patients’ perception of helpfulness. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8(1):41–48. | ||

Petrie KJ, Jago LA, Devcich DA. The role of illness perceptions in patients with medical conditions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(2):163–167. | ||

Leventhal H, Weinman J, Leventhal EA, Phillips LA. Health psychology: the search for pathways between behavior and health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:477–505. | ||

Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Breland JY. Cognitive science speaks to the “common-sense” of chronic illness management. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):152–163. | ||

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. | ||

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(4):351–379. |

Supplementary material

Below outlines the search strategy for Medline (with MeSH headings). This was adapted according to the indexing systems of the other databases searched.

# Searches

- exp Attitude to Health/ or illness perceptions.mp.

- illness representations.mp.

- health beliefs.mp. or exp Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice/

- beliefs about medicines.mp.

- beliefs about treatment.mp.

- patient experience.mp.

- drawings.mp.

- exp Art Therapy/

- visual arts.mp.

- visual representations.mp.

- 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6

- 7 or 8 or 9 or 10

- 11 and 12

- limit 13 to English language

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.