Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 15

Uptake of Trachoma Trichiasis Surgery and Associated Factors Among Trichiasis-Diagnosed Clients in Southern Tigray, Ethiopia

Authors Adafrie Y , Redae G , Zenebe D, Adhena G

Received 29 January 2021

Accepted for publication 6 April 2021

Published 10 May 2021 Volume 2021:15 Pages 1939—1948

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S302646

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Yeshialem Adafrie,1 Getachew Redae,2 Dawit Zenebe,2 Girmay Adhena3

1Department of Epidemiology, Ofla District Health Office, Tigray, Ethiopia; 2Department of Epidemiology, College of Health Science, Mekele University, Mekele, Ethiopia; 3Department of Reproductive Health, Tigray Regional Health Bureau, Tigray, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Girmay Adhena Tel +251 92257433

Email [email protected]

Background: Trachoma is the most common infectious cause of blindness in the globe. Trichiasis surgery is the best treatment option for this disease. Despite efforts done to eliminate blinding trachoma, there is limited evidence on the surgical uptake of trachoma trichiasis in Ethiopia. This study was aimed to assess the uptake of trachoma trichiasis surgery in Southern Tigray, Ethiopia.

Methods: Mixed cross-sectional study was employed among 409 participants. Study participants were selected using a consecutive sampling technique. Pretested and interviewer-administered data were collected using a structured questionnaire. Binary and multivariable logistic regression was done to identify associated factors. Adjusted odds ratios 95% CI was estimated to show the strength and direction. Variables with p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For qualitative data, 4 focus group discussions were conducted with 40 participants and described by thematic analysis then triangulated with quantitative findings.

Results: About 234 (57.9%, 95% CI: (53.2, 62.9)) participants utilized trachoma trichiasis surgery (TT). History of trachoma trichiasis (TT) for > 2 years [AOR: 0.4, 95% CI: (0.22, 0.72)], informed about surgery program by health workers [AOR: 0.3, 95% CI: (0.13, 0.71)], history of TT surgery [AOR: 0.18, 95% CI: (0.05, 0.6)], absence of someone to care the family [AOR: 14, 95% CI: (6.9, 28.6)], companion [AOR: 8.9, 95% CI: (4.3, 18.3)], nearby health facility [AOR: 2.4, 95% CI: (1.1, 5.4)], work load [AOR: 8.8, 95% CI: (4.6, 17)], fear [AOR: 4.3, 95% CI: (1.8, 10)], and believing eye drop can treat TT [AOR: 3.9, 95% CI: (1.4, 11)] were significantly associated factors.

Conclusion: More than half of the participants accepted the TT surgical uptake. Strengthening community awareness on proper eye care, and effective treatment options, and addressing the negative attitude towards surgical treatment in the community are important measures to achieve the elimination target of trachoma.

Keywords: trachoma trichiasis, surgery, uptake, Tigray, Ethiopia

Background

Trachoma is an infection of the eye caused by the bacteria called Chlamydia trachomatis, and it is the leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide.1 It causes active inflammation of the conjunctiva usually in childhood which if persisting or recurring can lead to scarring of the eyelid. These scars contract causing the eyelashes to turn inward and rub the cornea to cause a condition called trachoma trichiasis (TT). It is mainly a problem of the upper eyelid even it can also be found in the lower lids. The chronic sequelae of trachoma trichiasis occur in adults commonly 15 year’s age and above.2,3

About 2.2 million people are visually impaired as a result of trachoma in the globe, out of this, 1.2 million are blind, and 232 million people living in trachoma endemic districts are at risk. More than 21 million have active trachoma and about 7.3 million require trichiasis surgery.4–6 Africa is the worst affected continent with 18 million cases of active trachoma (85% global cases) and 3.2 million are in the advanced stage of trichiasis and require surgery to prevent them from blindness.7,8 Ethiopia and South Sudan have the highest prevalence of active trachoma.9

The level of eye care utilization among older adults in low- and high-income countries is only about 18% and ranging from 10% to 37%.10 The devastating consequences of the blinding disease trachoma trichiasis are often underestimated. The impacts are especially unforgiving in low-income countries where there is a lack of technology, lack of health care services, poor sanitation, unclean water supply, lack of support structures, and lack of regular face washing which allow the bacteria to infect and re-infect eyes of individuals living in trachoma-endemic areas.4,11

Trachoma trichiasis is the major risk factor for blindness and one person every 15 minutes become blind and one person experiences severe sight loss every 4 minutes worldwide.11-13 In addition to the misery and pain of trichiasis and the disability caused by blindness, trachoma causes dependency and is a barrier to development. The cost of disability and potential loss in productivity alone has been estimated to be more than 2 billion United States dollars per year.1

For blinding trachoma to eventually be eliminated as a public health problem, WHO endorsed an integrated strategy known as SAFE (surgery for people at immediate risk of blindness, antibiotic to treat active cases and reduce community reservoir, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvements to reduce transmission). Anyone with TT is recommended trichiasis surgery because of the difficulty in following up.2,14 Low uptake of TT surgery has always been a concern for the success of the trachoma control strategy. The uptake of trichiasis surgery remains a problem for many African countries including Ethiopia with surgical coverage lower than 50%. This is undermining the global effort to control blinding trachoma by the year 2020.15–19 To accomplish this, the surgery component of the SAFE strategy should be implemented in each country to reduce the number of people with trichiasis to less than one per 1000 people by availing of surgery.1

Ethiopia launched Vision 2020 in 2002 for eliminating blinding trachoma trichiasis as a public health problem in the country.4 Trachoma is the second leading cause of blindness in Ethiopia which accounts for about 12% of total blindness.20 Southern Tigray is among the trachoma trichiasis common areas in Ethiopia and evidence showed that about 1.9% to 2.3% of trichiasis cases were found in southern Tigray.21 Although Ethiopia’s National Program has achieved a significant scale-up of surgical activities, studies showed that there is still a gap in achieving annual trichiasis surgery targets. Among 665 districts trichiasis surgery needed only 33 districts to have trichiasis prevalence below the elimination threshold of 0.1%. The program supported only 44% of its annual target in 2016 and with this progress, reaching the global elimination of the trachoma 2020 plan will be difficult.7

Despite efforts were implemented to eliminate blinding trachoma through the SAFE strategy in Ethiopia, evidence showed that the prevalence of trachoma trichiasis was 2.9% after the initiation of SAFE intervention, which is still higher than the WHO-recommended elimination target of below 0.1%.1,15 Even though rural districts of the Southern Tigray region were identified by the global trachoma mapping project as among the districts that need surgical intervention,21 there was limited data on the utilization of surgical services and the progress towards trachoma elimination target in this area. Thus, this study was aimed to assess the uptake of trachoma trichiasis surgery and associated factors in Southern Tigray, Ethiopia.

Methods

Study Area and Period

The study was conducted in southern Tigray, Ethiopia. There are five rural and three urban administrative districts with a total population of 765,763 and out of this, 390,539 (51%) were females, and 375, 224 (49%) were males (Southern Tigray Zonal Finance and Planning Office and Zonal Health Department annual report of 2018; unpublished data; 2018). The zonal town, Machew is found 120 km away from Mekele, the capital city of Tigray, and 661 km away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Three general hospitals, two primary hospitals, 30 health centers, and 89 health posts were serving to the community. The zone is among SAFE strategy implementation areas in the region in which TT surgery is provided quarterly. Trichiasis surgery service was provided free of charge all over the zone by Light for the World in collaboration with the Tigray regional health bureau. A total of 22 public health facilities (2 hospitals, 13 health centers, and 7 health posts) were included. The study was conducted from April 10 to June 24, 2019.

Study Design

A campaign-based mixed cross-sectional study was used.

Source Population

All trichiasis clients who come to surgery sites of the zone were the source population. All clients who were diagnosed with trichiasis and counseled for surgery in the 22 surgery sites were the study population. For the qualitative part, focus group discussants were health development armies (HDAs), community leaders/steering committee of selected kebeles, health extension workers (HEWs), and health center supervisors at selected districts, and zonal eye care clinic health workers were included in the focused group discussion. All trichiasis patients aged 15 years and above who attended surgery sessions and are residents of the zone for at least six months were included in the study.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula (n = (Zα/2)2*p (1-p)/d2) for the first objective, where n is the required sample size, Z is the confidence level at 95%, p is the proportion of surgery utilization from the previous studies conducted in Gojam,23 and by adding 10% non-response rate the calculated sample size for the first objective was 409. The sample size for the second objective (factors) was also calculated using the Epi Info 7 version with the assumptions of 95% CI, 80% power, the exposed to unexposed ratio 1, and the sample size was 294. Since the sample size of the second objective (294) was less than the sample size of the first objective (409) then the final sample for this study was 409. The sample size for the qualitative part was determined based on the saturation of the idea. For the sampling procedure, all the 22 surgery sessions in the five rural districts of the zone were included and participants were selected using consecutive sampling techniques. From these outreach programs, 9 were from Raya Azebo, 6 from Ofla, 2 from Enda Mekoni, 3 from Raya Alamata, and 2 were from Alaje district. For the qualitative part, a purposive sampling technique was used to select for the focused group discussion (FGD).

Data Collection Tool and Techniques

The questionnaire used to collect data in this study was structured, pretested, and adopted from different studies (literature).14,17,19,22 It was translated to the local Tigrigna language by language experts (person). It includes background characteristics of participants such as age, sex, religion, ethnicity, educational status, occupation status, marital status, and family size. The questioner also includes patient experience-related characteristics, perception towards TT surgery, and other related characteristics. Patients diagnosed with trichiasis then counseled for surgery were interviewed before they undergo surgery for surgery acceptors and before they go back home for those refusals. Those who accept the surgery were coded as 1 and those who refuse the surgery were categorized as refusals and coded as 0. Data was collected by 16 health center supervisors and four health officers. Two Master’s degree holder health professionals and the principal investigators have supervised the data collection process. For the qualitative part, data were collected through FGD using open-ended questions prepared in the Tigrigna language. Field notes and tape recordings were undertaken using FGD guide questions. Participants were motivated to discuss each question actively with full involvement, and each discussion lasts for 60 to 65 minutes.

Data Quality Control

The questionnaire was first developed in English and translated to the local language (Tigrigna) and then back-translated to English by a language expert (person) to assure consistency. The pretest was done among 20 (5%) individuals in the first session of the outreach program. The two-day training was given to data collectors and supervisors on the aim of the study, how to administer the data collection process, purpose, risks, and research ethics before the data collection process. Data were checked daily throughout the data collection period to ensure its completeness and proper recording of the required information. Data were cleaned using SPSS version 22 by running frequencies and sorting cases for checking missing values and possible outliers. Co-linearity was checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all independent variables at VIF <10 (Tolerance >0.1), and no co-linearity exists between those variables. The model fitness was checked using Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit and the model fits at 0.682. For the qualitative part, calm discussion classes were selected for FGD, tape recording and note-taking were undertaken to control the consistency of information.

Data Analysis

Data were entered, coded, and checked using the Epi info 7 versions then exported to SPSS version 22 for analyses. Frequencies, proportions, narratives, tables, figures, and summary measures were used to describe the study population about relevant demographic variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was applied to explore the association of explanatory variables with the outcome variable. Variables with p-values <0.2 in the bivariate analysis were taken into the multivariate logistic regression model to check for the association by controlling the effect of confounders. Adjusted odds ratio at 95% CI was used to show the strength and direction of the association. Variables with a p-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the qualitative part, data obtained from FGD in Tigrigna was translated into English. The responses from the respondents were transcribed into themes and described using anecdotes, examples, and direct quotes of subjects. Narrative thematic analysis was performed, and then qualitative information was triangulated with the quantitative findings.

Ethical Clearance

Ethical clearance was secured from the Research Ethical Review Committee of Mekelle University before the data collection begins. A formal letter was given from Mekelle University to Tigray Regional Health Bureau, Southern zone district health offices, and each health facility. Voluntary, informed, signed, written consent was obtained from each participant, and the purpose of the study and their rights to stop responding at any time were explained to all participants. All personal information provided was kept confidential by coding.

Result

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Participants

Out of 409 expected participants, 404 were interviewed making a response rate of 98.8%. The mean age of the participants was 54.7 (SD± 14.5) years old. Near to half, 187 (46.3%) were above the age of 60 years old, and about 122 (30.2%) participants were in the age range of 45–59 years old. More than half 254 (62.9%) were females, about 400 (99%) were Tigray in their ethnicity, and the majority, 317 (78.5%) were orthodox in their religion. The majority, 256 (63.3%) of participants were married in their relationship status, and 368 (91%) were unable to read and write in their educational status. Ninety-one percent of respondents were farmers in their occupational status, and 377 (93.3%) had five and above family size (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Participants in the Southern Tigray, Ethiopia, 2019 |

Medical and Other-Related Characteristics of Participants

More than half, 208 (51.5%) participants had a history of trichiasis for more than two years, and three-fourth of them have practiced epilation at their home before arrival for surgery. The majority, 286 (70.8%) participants reported that they have no one to care for in their family, and 157 (38.9%) respondents reported they have a workload. Twenty-one (5.2%) participants reported having heard a negative rumor about trichiasis surgery either on the procedure or outcome of the service. Sixty-one (15.1%) participants report fear about surgical procedures (Table 2).

Trichiasis is not completely cured because I saw people in our neighborhood who had TT surgery before but it recurs back after a year and now they are still epilating. So, we need to have at least one better surgeon at Korem hospital who come from Mekele or give training to our doctors [40 years old male, FGD3]

|

Table 2 Medical and Other-Related Characteristics Among Participants in Southern Tigray, Ethiopia, 2019 |

More than 50% of study participants believed that TT is caused by poor hygiene, mourning, and smoke. Only 13.1% of participants reported that trichiasis can be transmitted by contact with an infected person.

TT can be transmitted from person to person by sharing tweezers and epilating others. [38 years old female, FGD2]

About 381 (94%) participants agreed that trichiasis can be treated by surgery. More than half (51.2%) of surgery refusals and about 28.2% of acceptors prefer alternative treatments like eye drop and epilation than surgery as a treatment of trichiasis.

TT is caused by smoking, mourning, poor personal and environmental hygiene, and dust [45 years old female, FGD2]

Smoke is a common cause of TT for females and dust for males [48 years old Male, FGD III]

Regarding the service-related characteristics, about 68 (16.8%) participants used a car to arrive at the surgery site. One-fifth, 85 (21%) participants come from a place that takes more than two hours of travel time. About 73 (18.1%) of participants have a previous history of TT surgery. One-fourth (25.7%) of participants reported absences of a companion to go back home and 56 (13.9%) reported no nearby health facility for follow-up service. Regarding the source of information on TT surgery, about 250 (61.9%) participants heard from community leaders, 75 (18.6%) from health care providers, 39 (9.7%) from family members, 22 (5.5%) individuals with previous TT surgery, and 18 (4.5%) heard the information by themselves.

Even though there is an improvement in reaching the community, the distance of surgery site is still difficult to address older patients who can’t come by themselves and for those who have no companion. [45 years old male, FGD1]

The reasons for surgery refusal were giving priority for temporary social activities like funerals, baptisms, marketing; fear of surgical procedure and being covered with an eye patch for a long time; and not understanding the consequences of being unoperated [50 years old male, FGD1]

The problem in counseling (like not using local language), late information dissemination, giving another appointment date, late arrival of health workers and long waiting time were main problems in our setting. [67 years old female, FGD2; 49 years old male FGD3; and 72 years old male FGD4]

There are remote areas we couldn’t address with the available manpower and surgery site. Older patients were not coming for the service when we had sites more than three hours of travel time for them. So we need additional manpower and surgery sites closer to home than the existing system. [27 years old male, FGD1]

Many people said the surgery is the best option to be treated from Trichiasis But, I disagree with this idea since Trichiasis can recur after surgery, we couldn’t generalize as surgery is the only treatment, we also need to avoid contact with smoke and dust. [57 years old male, FGD3]

The Uptake of Trachoma Trichiasis Surgery

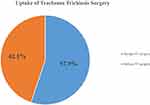

Among 404 interviewed participants, 234 [57.9%, 95% CI: (53.2, 62.9)] were accepted trachoma trichiasis surgery in this study (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Uptake of trachoma trichiasis surgery among trichiasis-diagnosed clients in Southern Tigray, Ethiopia, 2019. |

Factors Associated with the Uptake of Trachoma Trichiasis Surgery

In the Binary logistic regression analysis, duration of TT surgery, family care, accompany, working status, fear of surgery, attitude, treatment for trichiasis, source of information, and health facility status were significantly associated. However, in the final model (multivariable regression), participants who had TT for >2 years, being informed about surgery program by health workers, individuals with a history of TT surgery, absence of care from the family, companion, distance of the health facility, workload, fear, and believing eye drop can treat TT were significantly associated factors (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Factors Independently Associated with Trachoma Trichiasis Surgical Uptake in Southern Tigray, Ethiopia, 2019 (N= 404) |

Discussion

The prevalence of trachoma trichiasis surgery uptake in this study was 57.9% (95% CI: (53.2, 62.9)). Participants who had TT for above 2 years, being informed about surgery programs by health workers, individuals with a history of TT surgery, were less likely to refuse the surgery. Absence of someone to care for the family, companion, no nearby health facility, workload, fear, and believing eye drop can treat TT were significantly associated factors.

The magnitude of trichiasis surgical uptake in this study (57.9%) is in line with a study done in Tanzania (55.7%).23 The possible reason for the similarities might be due to the similarity in the place of the interview where both studies were held at fixed surgery sites, patients who come to outreach sites might have a similar desire towards surgical uptake. On the other hand, the acceptance rate in this study was higher than the studies conducted in Guragie (14.2%) and East Gojjam (43%).22,24 The possible reason for the discrepancy might be due to those studies that were conducted at the household level, there might be participants with less visual disturbance to seek surgical intervention who will prefer to live with TT than suffering from surgery pain when compared to outreach attendants. So, this may be the reason for the differences.

Factors significantly associated with TT surgical uptake were assessed in this study. Participants who have trichiasis for more than two years were 60.2% times less likely to refuse TT surgery service than those who have for two years or less. This is consistent with the studies conducted in Northern Ethiopia, and Mehal Saint (Ethiopia’s Amhara region) where patients who have a longer duration of illness were more likely to utilize surgical services than those who know the problem for a shorter duration.25,26 This might be because patients with a longer duration of TT might experience much pain and sight problems to prefer surgery for immediate relief.

Participants who reported there is no one to care for the family and themselves about surgery were 14.1 times more likely to refuse TT surgery than their counterparts. This is supported by findings in Tanzania, and Gurage.23,24 The possible reason might be due to perceptions towards TT surgery as they believed surgical wounds can take a long period to heal and restrict them from participating in different activities. The other reason may also the majority of the participants may have family members and they may be the only caregiver to the family member if so they may fear that if they undertake the surgery the family member may be at risk.

TT patients refuse the offer of surgery because they didn’t have anyone to care for the family while they are in surgery as it restricts them from exposing to fire and smoke and performing other productive works (at least for 40 days). [48 years old man FGD1, and 27 years old female FGD4]

I do have seven children but none of them are living with me. They do have their own family. Especially after my husband has died I live alone. At this time I need a person who gives me care including doing home activities. This is the time for me to go to the church and pray. But I am not doing this because of the problem that happens in my eye. Right now it is very difficult for me to fetch water from the river and to do home activities because my power is decreased in addition to the eye problem. [79 years old female; FGD3]

Participants who reported no companion to go home after surgery were 8.9 times more likely to refuse trichiasis surgery than their counterparts. This is consistent with the studies conducted in Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and India.15,16,23,27 This might be because patients who come alone could not go back home with a covered eye without a companion, especially those who come from remote areas they seek supporter. The other possible reason may also be that the majority comes from the rural, and difficult to reach areas where there may not be transport access and it takes a long time to reach their home. So during this time, they need a companion and this might be the possible reason for the refusal.

Older patients and patients who come from distant areas without companion commonly refused surgery especially when they were advised to have surgery on their two eyes since they couldn’t go back home with a covered eye. [74 years old man, FGD4]

Those who had a high workload were 8.8 times more likely to refuse trichiasis surgery compared with those who did not have a workload. This is supported by the studies conducted in India, and studies in Ethiopia.22,25,27 The possible reason might be due to the fact that rural residents have seasonal activities and strict socio-cultural values and they will prefer to remain with the pain of trichiasis until the next preferable outreach program than disappointing those social activities.

Patients will refuse surgery if they have funerals, baptisms, and other social roles in the community especially if they are family or community leaders because they give priority for those social activities and did not understand the risk of remaining with Trichiasis for extra time. [34 years old man FGD1, and 59 years old man, FGD3]

In the previous year, I heard that this service was ready to give service to the community. During that time I did not come to get the service because there was a marriage ceremony in my home. If I came and get the service during that time, I may not celebrate and express my feeling to the marriage ceremony of my daughter because the surgery may remain for a long time. [78 years old female, FGD3]

Fear of surgery is a significantly associated factor to hinder trichiasis’ surgical uptake in this study. This is consistent with the studies conducted in Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia that show fear of surgery as the main obstacle of trichiasis surgery.15,16,22,23,29 The possible reason could be due to those who fear the surgical procedure, pain, and also they may think they become blind due to the surgery. So, due to this, they may refuse the TT surgery.

Patients refuse surgery for fear of pain or damage from the procedure. (64 years old man, FGD3)

Patients fear TT surgery because they don’t have trust at some surgeons ‘tsebay deybilom’ (means they did not respect for patients) who were not good in counseling and poor in approach. (49 years old women, FGD4)

Patients who heard negative rumors about TT surgery either in the procedure or in the outcome of surgery were 11.7 fold more likely to refuse surgery than those who did not hear. This is supported by studies done in Ethiopia.26,27 The possible explanation for this could be due to those who have negative rumors about TT surgery may think they will face other eye problems and did not accept the treatment option. Hearing of false information might increase the community to refuse the TT surgery.

Patients didn’t want surgery especially at the age they were since they believe it will disfigure their eye after recovery of the wound. (82 years old male; FGD3)

Patients who believe eye drop as a treatment option for TT were 3.94 times more likely to refuse surgery than those who did not. This is consistent with the studies done in Tanzania and West Gojjam.23,28 A possible explanation could be due to the eye is a sense organ that is very vital for citation. Medicine for such sense organ is somehow given priority than to surgery due to fear of complication of the surgical procedure which may more likely increase refusal.

Patients who get information about the TT surgery program from health workers and individuals who have a history of TT surgery were less likely to refuse surgery than their counterparts. This is consistent with the study conducted in Tanzania.23 This might be due to the fact that health workers provide adjacent counseling about the service during information dissemination at their house to house visits. Besides, individuals with previous surgery can give tangible information about the importance of the service, and patients might have more trust in their neighbors who share similar life experiences and social interactions.

Those participants who reported that there was no near health facility were 2.42 times limiting the trichiasis surgical uptake than those who reported there is near health facility. This is supported by the studies conducted in Ethiopia, India, Ghana.15,22,23,26,27,29 The possible reason could be due to that if there is a near health facility they may be able to get access to the services and may easily visit the health facility without the difficulty of transportation which can save their time energy and cost.

Shortage of TT surgeons, absence of static site services, long waiting time and reappointment to the next day due to shortage of surgery instruments and late arrival of TT surgeons, program overlapping and lack of senior support from program managers. [34 years old man, FGD2, and 77 years old male, FGD3]

Limitation

This study is campaign-based, those patients who left at home may not include, and the consecutive sampling technique used to select study participants may affect its generalizability.

Conclusion

More than half of the participants utilized TT surgery. Having trachoma trichiasis (TT) for >2 years, being informed about surgery program by health workers, history of TT surgery, absence of someone to care for the family, companion, nearby health facility, workload, fear, and believing eye drop can treat TT were significantly associated factors. The regional health bureau and the zonal health department with the collaboration of other sectors should work strongly to achieve the elimination target of trachoma. Strengthen community awareness on proper hygienic practice, effective treatment options, and addressing the negative attitude towards surgical treatment in the community are important measures to decrease the problem.

Abbreviations

FGD, focused group discussion; HDA, health development armies; SAFE, surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvements; TT, trachoma trichiasis; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Consideration

The study was conducted following the declaration of Helsinki on human subjects. After the purpose, benefit and risk was briefed, informed consent was obtained from the study participants, who were all 18 years of age or older. Ethical clearance was secured by Mekelle University Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC). A formal letter was given by Mekelle University to Tigray Regional Health Bureau, southern zone district health offices, and each public health facility.

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate Mekele University and Southern Tigray for their support. Our appreciation also extends to participants for sharing their valuable information. We would like to be grateful to the Ethiopian field Epidemiology training program for providing financial support. Finally, we want to express our heartfelt thanks to data collectors and supervisors for their support throughout the data collection process.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The financial issue for this work was supported by the Ethiopian field Epidemiology training program.

Disclosure

The authors reported no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Emerson P, Frost L, Bailey R, Mabey D. Implementing the SAFE Strategy for Trachoma Control: A Toolbox of Interventions for Promoting Facial Cleanliness and Environmental Improvement. International Trachoma Initiative; 2006.

2. CDC. Guidelines for the Management of Trachoma in the Northern Territory. International Trachoma Initiative; 2008.

3. Merbs S, Resnikoff S, Kello AB, Mariotti S, Greene G, West SK. Trichiasis Surgery for Trachoma.

4. Bedri A, Etya’ale D, Filipec M, et al. Vision and development; Ophthalmology in Development Cooperation. Int Trachoma Initiative. 2013;1(1).

5. Cromwell E, Courtright P, King J, Rotondo L, Ngondi J, Emerson P. The excess burden of trachomatous trichiasis in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009:103(10):985-992.

6. ICTC. Thirteenth Annual Trachoma Control Program Review: “Sharing Programs to Fit the Need: The Relevance of Prevalence”. The Carter Center; 2012.

7. Hussman JP, Hussman T, Yemaneberhan T. Eighteenth Annual Trachoma Program Review Atlanta Georgia. The Carter Center; 2017.

8. ICTC. The End Insight: 2020 INSight International Colation for Trachoma Control; 2011.

9. WHO. Alliance for the Global Elimination of Blinding Trachoma; 2014:421–428

10. Vela C, Samson E, Zunzunegui MV, Haddad S, Aubin M-JE, Freeman EE. Eye care utilization by older adults in low, middle, and high income countries. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12(1):5. doi:10.1186/1471-2415-12-5

11. Habtamu E, Rajak SN, Gebre T, et al. Clearing the backlog: trichiasis surgeon retention and productivity in Northern Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(4):e1014. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001014

12. Bowman R, Faal H, Myatt M, et al. Longitudinal study of trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(3):339–343. doi:10.1136/bjo.86.3.339

13. Roniger R, Hove TT, Elsen J, Sochorova’ L. Vision and development: end in sight for blinding Trachoma. Light World. 2013;1(1).

14. Foster A, Resnikoff S. The impact of Vision 2020 on global blindness: London school of hygiene and tropical medicine. Eye. 2005;19(1):1133–1135.

15. Roba AA, Wondimu A, Eshetu Z. Effect of SAFE intervention on pattern of barriers to Trichiasis surgery. J Community Med Health Educ. 2012;2(7):162.

16. Ng’etich AS, Owino C, Juma A. Utilization of trachoma eye care services in central division of Kajiado County, Kenya. Int Res J Public Environ Health. 2016;3(3):32–46.

17. Mahande M, Tharaney M, Kirumbi E, et al. Uptake of trichiasis surgical services in Tanzania through two village-based approaches. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(2):139–142. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.103374

18. Burton M, Courtright P, Emerson P Global scientific meeting on trachomatous trichiasis: meeting discussions, conclusions & suggested research.

19. Habtamu E, Rajak SN, Tadesse Z, et al. Epilation for minor trachomatous trichiasis: four-year results of a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(3):e0003558. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003558

20. Yemane B, Alemayehu W, Abebe B. National Survey on Blindness, Low Vision and Trachoma in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia; 2006.

21. Sherief ST, Macleod C, Gigar G, et al. The prevalence of Trachoma in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia: results of 11 population-based prevalence surveys completed as part of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(sup1):94–99. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1250917

22. Aredo KK, Kebede AB, Aychiluhim M, Hordofa MA. Determinants of eye lid surgical care utilization among Trachomatous Trichiasis patients in rural communities: in the case of Basoliben District. North West Ethiopia Am J Intern Med. 2014;2(6):156–161. doi:10.11648/j.ajim.20140206.20

23. Bickley RJ, Mkocha H, Munoz B, West S, Vinetz JM. Identifying patient perceived barriers to Trichiasis Surgery in Kongwa District, Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(1):e0005211. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005211

24. Muluken M, Wondu A, Eva F, Paul C. Indirect costs associated with accessing eye care services as a barrier to service use in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9(3):426–431. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01205.x

25. Habte D, Gebre T, Zerihun M, Assefa Y. Determinants of uptake of surgical treatment for trachomatous trichiasis in North Ethiopia. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15(5):328–333. doi:10.1080/09286580801974897

26. Meshesha TD, Senbete GH, Bogale GG. Determinants for not utilizing trachomatous trichiasis surgery among trachomatous trichiasis patients in Mehalsayint District. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(7):e0006669.

27. Srinivas M, Rohit K, Konegari S, Gullapalli R. A population-based cross-sectional study of barriers to uptake of eye care services in South India: the Rapid Assessment of Visual Impairment (RAVI) project. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005125. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005125

28. Rajak SN, Habtamu E, Weiss HA, et al. Why do people not attend for treatment for trachomatous trichiasis in Ethiopia? A study of barriers to surgery. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(8):e1766. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001766

29. Bowman R, Soma O, Alexander N, et al. Should trichiasis surgery be offered in the village? A community randomized trial of village vs. health center based surgery. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5(8):528–533. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00605.x

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.