Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 10

The interactive web-based program MSmonitor for self-management and multidisciplinary care in multiple sclerosis: utilization and valuation by patients

Authors Jongen PJ , Sinnige L, van Geel B, Verheul F, Verhagen W, van der Kruijk R, Haverkamp R, Schrijver H, Baart C, Visser L, Arnoldus E, Gilhuis H, Pop P, Booy M, Heerings M, Kool A, van Noort E

Received 5 August 2015

Accepted for publication 22 December 2015

Published 3 March 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 243—250

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S93786

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Peter Joseph Jongen,1,2 Ludovicus G Sinnige,3 Björn M van Geel,4 Freek Verheul,5 Wim I Verhagen,6 Ruud A van der Kruijk,7 Reinoud Haverkamp,8 Hans M Schrijver,9 Jacoba C Baart,10 Leo H Visser,11 Edo P Arnoldus,12 Herman Jacobus Gilhuis,13 Paul Pop,14 Monique Booy,15 Marco Heerings,16 Anton Kool,17 Esther van Noort17

1Department of Community and Occupational Medicine, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, 2MS4 Research Institute, Nijmegen, 3Multiple Sclerosis Centre Leeuwarden, Medical Centre Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden, 4Department of Neurology, Medical Centre Alkmaar, Alkmaar, 5Department of Neurology, Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda, 6Department of Neurology, Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, 7Department of Neurology, Slingeland Hospital, Doetinchem, 8Department of Neurology, Zuwe Hofpoort Hospital, Woerden, 9Multiple Sclerosis Centre, Westfries Gasthuis, Hoorn, 10Department of Neurology, Ziekenhuisgroep Twente, Almelo-Hengelo, 11Multiple Sclerosis Centre Midden Brabant, St Elisabeth Hospital, Tilburg, 12Multiple Sclerosis Centre Midden Brabant, Tweesteden Hospital, 13Department of Neurology, Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis, Delft, 14Department of Neurology, Viecuri Medical Centre, Venlo-Venray, 15Multiple Sclerosis Centre, Amphia Hospital, Breda, 16MH Advies en organisatiebureau, Assen, 17Curavista bv, Geertruidenberg, the Netherlands

Background: MSmonitor is an interactive web-based program for self-management and integrated, multidisciplinary care in multiple sclerosis.

Methods: To assess the utilization and valuation by persons with multiple sclerosis, we held an online survey among those who had used the program for at least 1 year. We evaluated the utilization and meaningfulness of the program’s elements, perceived use of data by neurologists and nurses, and appreciation of care, self-management, and satisfaction.

Results: Fifty-five persons completed the questionnaire (estimated response rate 40%). The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Profile (MSIP), Medication and Adherence Inventory, Activities Diary, and electronic consultation (e-consult) were used by 40%, 55%, 47%, and 44% of respondents and were considered meaningful by 83%, 81%, 54%, and 88%, respectively. During out-patient consultations, nurses reportedly used the MSmonitor data three to six times more frequently than neurologists. As to nursing care, more symptoms were dealt with (according to 54% of respondents), symptoms were better discussed (69%), and the overall quality of care had improved (60%) since the use of the program. As to neurological care, these figures were 24%, 31%, and 27%, respectively. In 46% of the respondents, the insight into their symptoms and disabilities had increased since the use of the program; the MSIP, Activities Diary, and e-consult had contributed most to this improvement. The overall satisfaction with the program was 3.5 out of 5, and 73% of the respondents would recommend the program to other persons with multiple sclerosis.

Conclusion: A survey among persons with multiple sclerosis using the MSmonitor program showed that the MSIP, Medication and Adherence Inventory, Activities Diary, and e-consult were frequently used and that the MSIP, Medication and Adherence Inventory, and e-consult were appreciated the most. Moreover, the quality of nursing care, but not so neurological care, had improved, which may relate to nurses making more frequent use of the MSmonitor data than neurologists.

Keywords: patient-reported outcome, impact, adherence, diary, inventory, e-consult

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory and degenerative disease of the central nervous system that mostly presents itself in young adulthood. In ~80% of the persons with MS (PwMS), the first phase of the disease is characterized by recurrent episodes of symptoms that are typically followed by complete or partial remissions: relapsing remitting MS (RRMS).1 In spite of the fact that disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) reduce the frequency and severity of relapses, after about 15 years, most persons with RRMS seem to progress to the secondary progressive phase, experiencing a steady and unstoppable increase in disabilities.2 The multifocal localizations of the tissue lesions account for the wide variety of symptoms and signs that may appear in the course of the disease.

The optimal use of DMDs requires an early start3 and an adequate monitoring of disease activity.4 In recent years, neurological assessments are increasingly being complemented by PwMS’ self-assessments. The ensuing patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are used to monitor the disease course and the effectiveness of DMDs and symptomatic treatments.5 PROs inform the neurologist, MS-nurse, and other health care professionals on PwMS’ condition from the patient’s perspective. Equally important, PROs can be used by PwMS themselves for self-management purposes. To optimize the use of PROs for self-management and integrated multidisciplinary care in MS, we developed the interactive web-based program MSmonitor. A previous paper described its concept, content, and pilot results.6 To assess PwMS’ utilization of and satisfaction with the program and its components and functionalities, we conducted a survey. Here we report the results.

Methods

The MSmonitor program

At the time of the survey (January 2013), the MSmonitor program comprised ten components and functionalities in four categories: questionnaires, inventories, diaries, and electronic consultation (e-consult).

The questionnaires are psychometrically validated self-report instruments, the scores of which are generated automatically and are presented in graphs and tables to the patient and the authorized health care professionals. The questionnaires include the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Profile (MSIP), Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQoL-54) questionnaire, Modified Fatigue Impact Scale-5 Item Version (MFIS-5), Leeds Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life (LMSQoL) questionnaire, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. For a detailed description, please refer to Jongen et al.6 In brief, the MSIP comprises 36 questions assessing disabilities and disabilities perception in seven domains and four symptoms.7–9 It provides a complete overview of MS-related symptoms and their subjective valuation. The MSQoL-54 is a MS-specific measure of patient-centered mental and physical health status, and consists of the Short Form 36-Item health survey as a generic core measure, supplemented with 18 questions on items relevant to PwMS.10 The MFIS-5 is a short five-item questionnaire examining a patient’s perceived impact of fatigue on a variety of daily activities over the past month.11 The LMSQoL is a self-assessment scale that consists of eight questions, examining MS-related aspects of quality of life over the past month.12,13 The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a 14-item, self-report questionnaire for anxiety and depression.14

The Miction Inventory provides a complete overview of urological symptoms in MS, and the Medication and Adherence Inventory yields a patient-reported update of medication, the number of missed DMD doses in the last month, and, if applicable, the date and reason of a premature DMD discontinuation. The Activities Diary records the type and duration of activities and rest periods over a 24-hour period, and the Miction Diary documents the frequencies and quantities of micturitions and fluid intakes over a 24-hour period. The e-consult enables PwMS to contact their health care professionals. At the time of the survey, the e-consult did not enable communication between health care professionals. The MSIP, MSQoL-54, MFIS-5, and LMSQoL questionnaires, Medication and Adherence Inventory, diaries, and e-consult were available to all the participating PwMS. The MFIS-5, LMSQoL, and Medication and Adherence Inventory can be used monthly; the MSIP at least 6-monthly and at most monthly; the MSQoL-54 annually; the diaries daily; and the e-consult per required need. The combined use of MFIS-5, LMSQoL, and Medication and Adherence Inventory (“Quickscan”) enables quick, monthly assessments of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), fatigue experienced, medication, and DMD adherence. The neurologist, nurse, or other health care professionals make the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Miction Inventory available on indication, and also decide on the frequency of use.

MSmonitor is a care project and has therefore not been submitted to an ethical committee or the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects, in accordance with the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act of 1999 (http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0009408).15 At the start of participation in MSmonitor, patients were asked to give their informed consent for analysis of their anonymized data for research purposes. Patients could start with and use MSmonitor irrespective of this consent. Technical and security aspects of the program have been described.6

Survey

In the first quarter of 2013, we held an online survey among PwMS using the MSmonitor program. Those who started using the program at least 1 year before the date of survey were eligible. The data collection started on January 1, 2013 and ended on April 1, 2013. The closure of the database was April 15, 2013.

As the study was an observational survey, with no intervention, and a duration of completion of the questionnaire of ~20 minutes, the study did not require being reviewed by an ethical committee or the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects, according to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act of 1999 (http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0009408).15 Consequently, a waiver or approval was not requested. The authors had no access to any personal or identifying information in their analyses. All data were completely anonymized prior to review by the authors.

MSmonitor neurologists and nurses were asked to inform PwMS about the survey and invite them to participate. The information given to potential respondents concerned the purpose of the survey, the kind of data that were obtained, where the data were stored, and who the principal investigator (PJJ) was. No incentives were offered. The neurologists and nurses did not keep record of which patients or how many patients were actually contacted. The authors including LGS, BvG, FV, WIV, RvdK, RH, HS, JCB, LHV, EA, HJG, PP, MB, neurologists, and a specialized nurse were potentially involved in the treatment or health care of the survey participants. However, as the survey did not ask for the names of the health care providers, we were not informed if these authors actually did treat or provide health care to respondents. The authors who performed the analyses of the anonymized data (PJJ, MH) were not involved in the treatment or health care.

After having received a personal code, respondents logged on to the study website of the MS4 Research Institute, then http://ms4ri.net/ms4-research, to choose a username and password. The survey was performed using the LimeSurvey™ software (LimeSurvey Project Team, Carsten Schmitz, Hamburg, Germany), an open source online application for surveys. There was no testing of the MS4 Research Institute’s platform for this survey since it had already being used in various research projects. The responses were automatically captured. To protect the personal data from unauthorized access, various mechanisms were used to comply with European Union regulations concerning online medical data, including the use of a personal username and password, separation in the database of personal information from the answers to the questions, and each screen having a username and password protection. The items of the questionnaire were fixed, and adaptive questioning was not used. Automated completeness checks were done before questionnaires could be submitted. The respondents had an overview of all questions and answers before submission and they could change the answers before submitting. After submission, changes were no longer possible. Only completed questionnaires were analyzed. The help desk (MH) contacted respondents by phone in case they did not succeed in completing the questionnaires. No methods were used to adjust for nonrepresentativeness of the sample.

The survey comprised 54 questions pertaining to: 1) the components and functionalities actually being used (Yes, No per item), 2) the meaningfulness of the components and functionalities (Yes, No, No opinion, Not applicable per item), 3) the degree of utilization of data by the neurologist and nurse during out-patient visits (No, Scarcely, Regularly, Often, Always per item), 4) data utilization by the neurologist and nurse with respect to quality of care (Yes, No per item), 5) self-management (Yes, No per item; free text), 6) the importance of other health care professionals having access to the data (rehabilitation doctor Yes, No; urologist Yes, No; continence nurse Yes, No; general physician Yes, No; psychologist/psychiatrist Yes, No; free text), 7) advantages and disadvantages of the program (free text), 8) reasons for noncompletion of questionnaires, inventories, or diaries (lack of time Yes, No; having no symptoms Yes, No; do not feel like it Yes, No; problem to log in Yes, No; other website-related problems Yes, No; free text), 9) suggestions for improvement (free text), 10) ease of use (Likert 5-point scale), and 11) overall satisfaction (Likert 5-point scale) and recommendation of the program to other PwMS (Yes, No). Respondents were registered using date of birth and email address and there were no duplicate registrations.

Results

Response

Fifty-five PwMS responded and completed the questionnaire. Given that the number of eligible persons was 264 (those who as on January 1, 2012 made use of the program) and presuming that during the 3-month survey period 50% of these have been contacted, we estimated the response rate to be 40%. The female-to-male ratio of respondents was 4.5:1, and the mean (standard deviation) age 46.3 years (11.8). Thirty-eight persons had RRMS, eleven secondary progressive MS, four primary progressive MS, and one clinically isolated syndrome. The respondents were from all eight eligible hospitals. The number of respondents per hospital ranged between two and 13.

Utilization of components and functionalities

The percentages of PwMS who actually used a specific component or functionality of the program are presented in Figure 1.

The percentages of users who considered the use of the respective component or functionality as meaningful are presented in Figure 2.

The MSIP questionnaire (N=30), Medication and Adherence Inventory (N=26), Activities Diary (N=26), and e-consult (N=24) were used by approximately half of the respondents. In contrast, the other components and e-logbook were used by 16% or less of the respondents. The aforementioned four components and functionality were considered meaningful by 83.3% (MSIP), 80.8% (Medication and Adherence Inventory), 53.8% (Activities Diary), and 87.5% (e-consult) of the respective users.

Utilization of data by neurologist and nurse

The degree to which the neurologist and nurse made use of the MSmonitor data during the out-patient visits – by having a look at the questionnaires, inventories, or diaries, or discussing data, scores, or single items – differed between the neurologist and nurses (Table 1). A comparison of the combined “often” and “always” categories between neurologists and nurses suggests that the nurses used the data approximately three to six times more frequently than the neurologists.

| Table 1 Degree of utilization of the MSmonitor data by the neurologist and nurse during out-patient visits according to PwMS (N=55) |

Quality of care

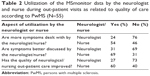

To assess the effect of the MSmonitor program’s use on the quality of neurological and nursing care, we asked PwMS whether since their use of the program more symptoms were dealt with, symptoms were better discussed, or the overall quality of care had improved during the out-patient visits (Table 2). Whereas 54%–68% of the replies were affirmative with respect to the nursing care, only 23%–30% were so with respect to the neurological care.

Self-management

As to the self-management aspects of the MSmonitor use, 46% of the respondents reported to have gained better insight into their symptoms or disabilities, whereas 18% could better handle their symptoms or disabilities (Table 3). In both categories, it were the MSIP questionnaire, Activities Diary, and e-consult that most often were considered to have contributed to these positive changes. The degree to which PwMS suffered from symptoms or disabilities had not changed.

Data access

A majority (56.4%) of PwMS thought it important that other health care professionals could have access to their data, especially the family doctor (49%), rehabilitation doctor (30%), and urologist (24%).

Advantages and disadvantages

The reported advantages of the program’s use included the regular availability of an overview of all symptoms and problems; gaining insight into symptoms and problems; easier access to start a conversation with neurologist or nurse; more items discussed with neurologist or nurse; direct mail contact (e-consult); being forced to reflect on symptoms and problems; availability of a medical file in spite of infrequent out-patient visits; possibility to look back on previous symptoms and problems; better preparation for out-patient visits; and contact with Dutch health care professionals in spite of living abroad.

The reported disadvantages were that the program’s use was sometimes too tiring; involved a lot of work; was too complicated; repeated the same questions, even when the situation was stable; Activities Diary was too general; confronting; impossible to answer “Not Applicable”; had to remember to look at email; neurologist does not make use of data; grammatical errors; no space for free text; monthly completion is too frequent; the picture presented by the data is just a snapshot given the fluctuation of symptoms; difficulty with log in procedure; and not user friendly.

Reasons for noncompletion

The following reasons were mentioned for not completing questionnaires, inventories, or diaries: lack of time; absence of symptoms; did not feel like it; difficulties with logging in; problems with website; sometimes too tired; unable to open mail; unclear what to complete; cannot document my own symptoms; do not see the point of it; no change in symptoms; too confronting; completion of the same questions over and again; and not suitable for an iPad or tablet.

Suggestions for improvement

The suggestions for improvement included: option to ask questions to health care professionals prior to the out-patient visit; make the site more user friendly; add a page to include personal remarks in addition to questionnaires for the neurologist and nurse; enable completion without interruptions due to technical problems; easier log in procedure; automatic correction of typos; add an open diary; friendlier layout; unambiguous language use; make the program more patient-oriented and less professional-oriented; fewer questions; make graphs more accessible; enable a short description of changes during the last month; less technical problems; friendlier for iPad use; use fewer general questions; improve accessibility; and include an announcement when the next questionnaires are to be completed.

Ease of use

The ease of use of the program was rated on a Likert-scale from 0 (no ease of use) to 5 (maximum ease of use). The mean ease of use score was 3.51.

Overall satisfaction and recommendation

The overall satisfaction with the program was rated on a Likert-scale from 0 (no satisfaction) to 5 (maximum satisfaction). The mean ease of use score was 3.52. When asked if they would recommend the use of the MSmonitor program to other PwMS, 40 (72.7%) of the respondents answered they would do so.

Discussion

By use of a survey, we assessed the utilization and appreciation of the interactive web-based program MSmonitor by PwMS. The program’s main goals are the enhancement of self-management and improvement of integrated multidisciplinary care. The pilot phase of the program’s development was conducted from 2009 to 2014. The data provided by the survey, which took place during the first quarter of 2013, are qualitative and semiquantitative, their presentation descriptive, and the analysis explorative without statistical testing.

Of the ten components and functionalities that were available at the time of the survey, four were clearly favored by PwMS: the MSIP, Medication and Adherence Inventory, Activities Diary, and e-consult were used by about half of the respondents. It was also obvious that during out-patient visits, nurses used the MSmonitor data more frequently than neurologists. Consequently, the number of respondents who considered the quality of out-patient nursing care to have gained from the program was about twice as high as that regarding the neurological care. In addition, patients’ insight into symptoms and problems had increased since the use of the program, and the MSIP, Medication and Adherence Inventory, and e-consult were thought to have contributed most to this improvement. One out of two persons would like to have their MSmonitor data made available to the general physician, and one out of three to the rehabilitation doctor. Overall, the satisfaction with the program was reasonable (3.5 out of 5) and three of four respondents would recommend the program to other PwMS.

The MSIP comprehensively lists and scores MS-related disabilities and perceptions of disabilities in seven domains and four symptoms.7–9 Our findings suggest that the use of the MSIP was instrumental in improving the quality of nursing care and of self-management. We conceive these processes to take place as follows: up to a week before the out-patient visit the patient completes the MSIP; the color coding of worsened symptoms, their subjective valuations, and the listing of the changes on the dashboard’s overview section, all increase the patient’s awareness of his or her condition; the nurse takes a look at the MSIP data before the out-patient visit; and during the visit, the patient–nurse interaction is guided by the MSIP data, rendering the onsite visit more effective and efficient. Thus, the online MSIP is embedded in the onsite process of nursing care.

The Medication and Adherence Inventory lists medications, missed DMD doses, and the dates of eventual premature DMD discontinuation. Although it was frequently used and did contribute to a better insight, we are not sure about how this effect was obtained. Possibly, the monthly self-report of medication and of missed DMD doses per se had a positive effect on the awareness of adherence, and indirectly constituted an adherence promoting factor.

As suggested by the pilot results,6 the use of the Activities Diary, apart or together with the MFIS-5 and LMSQoL (“Quickscan”), may have facilitated the self-management of fatigue. This, in combination with the fact that fatigue is one of the most frequent and disabling symptoms in MS irrespective of disease activity or disease course, may explain the popularity of the Activities Diary among MSmonitor users and its efficacy in increasing insight into symptoms and disabilities.

The e-consult functionality enables patients to quietly formulate their question during a time of day that suites them, thus avoiding difficulties in getting connected by phone with the neurologist or nurse during busy office hours, or even having to make an appointment for an out-patient consultation. Moreover, the daily activities of the neurologist and nurse are not disturbed by unexpected or lengthy phone calls. In all, the e-consult functionality seems to facilitate an effective and efficient communication. The MSmonitor program is in development and some of the disadvantages reported in the survey have since then been resolved and suggestions implemented; technical failures have been remedied, the text and layout improved, space for free text added, and iPad, tablet, and smart phone applications developed.

Initiatives similar to the MSmonitor project have been described. A recent controlled study investigated the effectiveness of providing HRQoL scores in children with cancer to the pediatric oncologist.16 It was found that presenting HRQoL data increased discussion of emotional functioning and psychosocial functioning, was associated with less unidentified emotional problems, and improved HRQoL of patients 5–7 years of age with respect to self-esteem, family activities, and psychosocial functioning.16 Importantly, the duration of the consultation was not lengthened and the authors recommend the implementation of systematic monitoring HRQoL in children with cancer in clinical practice.16 These results are in line with our findings in adult MS patients on improved quality of care in relation to PRO-based monitoring.16 The Swedish MS registry, which has been active since 2001 and web-based since 2004, was designed to assure quality health care for patients with MS.17 It runs on government funding only, is used in all Swedish neurology departments, and currently includes data on over 80% of Sweden’s MS patients.17 Recent development includes a portal allowing patients to view a summary of their registered data and to report a set of PROs.17 In spite of differences (eg, regarding funding), the similarities between the Swedish MS registry and MSmonitor are obvious. The higher participation rate in the Swedish MS registry may be explained by the longer existence of the Swedish registry, the backing and funding by the Swedish government, and the organization of the Swedish health care system.

Based on the results of our survey, we consider focusing on the following developments and areas of application. First, attention to a better embedding of the program in the daily care processes in the out-patient clinic, especially as far as the neurologists are concerned.18 Second, a focus on usages that have been proven promising, such as the MSIP for the nursing care, e-consult functionality, self-management option of the Activities Diary and MFIS-5 usage, and Medication and Adherence Inventory to self-monitor drug adherence. Third, in view of the widely accepted goal to maximally prevent disease activity in the first years of RRMS, it is paramount to optimally use the various DMDs that are now available. This means a close clinical monitoring of disease activity in untreated patients and of wanted and unwanted effects in the treated ones. HRQoL, for example, as measured by the MSQoL-54, is an overall measure of a patient’s well-being, integrating relevant aspects of both disease and treatment. Moreover, measures such as the MSIP and MSIS-2919 quantify MS-related disabilities, and these online tools may compensate for the neurologists’ inconsistent use of the time-consuming Expanded Disability Status Scale in daily practice. Fourth, in the context of self-management, self-screening may become more important. Thus, we envisage adding the Actionable questionnaire to the program for screening and self-screening of MS-related bladder disturbances.20,21

Conclusion

The MSIP questionnaire, Medication and Adherence Inventory, and e-consult were the elements of the MSmonitor program that were used most frequently by PwMS; the use of these elements was highly appreciated and was thought to have improved the insight into symptoms and disabilities. PwMS also reported that the quality of nursing care had improved since they made use of the program.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the members of the MSmonitor Working Group: Ludovicus G Sinnige, Ytsje Dijkstra, Petra Scherstra (Multiple Sclerosis Centre Leeuwarden, Medical Centre Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden, the Netherlands); Björn van Geel, Chantal van Vliet (Department of Neurology, Medical Centre Alkmaar, Alkmaar, the Netherlands); Freek Verheul, Tiny Janssen, Annette Bruinings (Department of Neurology, Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda, the Netherlands); Jiske Fermont, Ron van Dijl, Monique Booy (Amphia Ziekenhuis, Breda, the Netherlands); Wim Verhagen, Gert van Dijk, Helma Borgers-Driessen (Department of Neurology, Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands); Ruud van der Kruijk, Jorine van Vliet (Department of Neurology, Slingeland Hospital, Doetinchem, the Netherlands); Joost Kerklaan, Sonja de Jong-Stoekenbroek (Department of Neurology, Zuwe Hofpoort Hospital, Woerden, the Netherlands); Hans Schrijver, Marja Lödel, Barbara van Someren-Achterberg (Multiple Sclerosis Centre, Westfries Gasthuis, Hoorn, the Netherlands); Leo H. Visser, Vanessa Hens (Multiple Sclerosis Centre Midden Brabant, St. Elisabeth Hospital, Tilburg, the Netherlands); Edo Arnoldus, Lisette Trommelen (Multiple Sclerosis Centre Midden Brabant, Tweesteden Hospital, Tilburg, the Netherlands); Jolijn Kragt, Anita Neele (Department of Neurology, Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis, Delft, the Netherlands); Paul Pop, Thea Bergmans-Barents (Department of Neurology, Viecuri Medical Centre, Venlo-Venray, the Netherlands); Elske Hoitsma, Ilona de Beer, Jolanda van Gorkum (Department of Neurology, Diaconessenhuis Leiden, the Netherlands); Astrid Ruys-van Oeyen, Corinne van den Berg (Department of Neurology, Rijnlandziekenhuis, Leiderdorp, the Netherlands); and Erna Bakker, Harry van Leusen, Jur Niewold (Scheper Ziekenhuis, Emmen, the Netherlands). We thank the members of the Scientific Advisory Board for their advice. We thank Jessica Groenenboom for the organization of the survey and the analysis of the data. The MSmonitor project is funded by Teva Netherlands via an independent and unrestricted grant.

Disclosure

Peter Joseph Jongen has received honoraria from Allergan, Biogen-Idec, Merck-Serono, Novartis, sanofi-aventis, and Teva for contributions to symposia as a speaker or for consultancy activities. Anton Kool and Esther van Noort are owners of Curavista bv. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Lublin FD. New multiple sclerosis phenotypic classification. Eur Neurol. 2014;72 Suppl 1:1–5. | ||

Trojano M, Pellegrini F, Fuiani A, et al. New natural history of interferon-beta-treated relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2007; 61(4):300–306. | ||

Freedman MS, Comi G, De Stefano N, et al. Moving toward earlier treatment of multiple sclerosis: findings from a decade of clinical trials and implications for clinical practice. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014; 3(2):147–155. | ||

Rotstein DL, Healy BC, Malik MT, Chitnis T, Weiner HL. Evaluation of no evidence of disease activity in a 7-year longitudinal multiple sclerosis cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(2):152–158. | ||

Jongen PJ, Sanders E, Zwanikken C, et al. Adherence to monthly online self-assessments for short-term monitoring: a 1-year study in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients after start of disease modifying treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:293–300. | ||

Jongen PJ, van Geel B, Verheul F, et al. The interactive web-based program MSmonitor for self-management and multidisciplinary care in multiple sclerosis: concept, content and pilot results. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1–10. | ||

Wynia K, Middel B, van Dijk JP, de Ruiter H, de Keyser J, Reijneveld SA. The Multiple Sclerosis impact Profile (MSIP). Development and testing psychometric properties of an ICF-based health measure. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(4):261–274. | ||

Wynia K, Middel B, de Ruiter H, van Dijk JP, de Keyser JH, Reijneveld SA. Stability and relative validity of the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Profile (MSIP). Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(14):1027–1038. | ||

Wynia K, Wijlen AV, Middel B, Reijneveld S, Meilof J. Change in disability profile and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: a five-year longitudinal study using the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Profile (MSIP). Mult Scler. 2011;18(5):654–661. | ||

Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Harooni R, Myers LW, Ellison GW. A health-related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(3):187–206. | ||

Fisk JD, Ritvo PG, Ross L, Haase DA, Marrie TJ, Schlech WF. Measuring the functional impact of fatigue: initial validation of the fatigue impact scale. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18 Suppl 1:S79–S83. | ||

Ford HL, Gerry E, Tennant A, Whalley D, Haigh R, Johnson MH. Developing a disease-specific quality of life measure for people with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15(3):247–258. | ||

Ford HL, Gerry E, Johnson MH, Tennant A. Health status and quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(12): 516–521. | ||

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. | ||

MoHWa S. Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). Int Publ Ser Health, Welfare Sport. 1997;(2):1–34. | ||

Engelen V, Detmar S, Koopman H, et al. Reporting health-related quality of life scores to physicians during routine follow-up visits of pediatric oncology patients: is it effective? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012; 58(5):766–774. | ||

Hillert J, Stawiarz L. The Swedish MS registry – clinical support tool and scientific resource. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132(199):11–19. | ||

Berg M, Aarts J, van der Lei J. ICT in health care: sociotechnical approaches. Methods Inf Med. 2003;42(4):297–301. | ||

Hobart J, Lamping D, Fitzpatrick R, Riazi A, Thompson A. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): a new patient-based outcome measure. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 5):962–973. | ||

Bates D, Burks J, Globe D, et al. Development of a short form and scoring algorithm from the validated actionable bladder symptom screening tool. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:78. | ||

Burks J, Chancellor M, Bates D, et al. Development and validation of the actionable bladder symptom screening tool for multiple sclerosis patients. Int J MS Care. 2013;15(4):182–192. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.