Back to Journals » Biologics: Targets and Therapy » Volume 10

Tocilizumab in refractory rheumatoid arthritis: long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability beyond 2 years

Authors Farah Z, Ali S, Price-Kuehne F, Mackworth-Young C

Received 25 November 2015

Accepted for publication 26 January 2016

Published 22 March 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 59—66

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S101289

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Doris Benbrook

Ziad Farah, Sabreen Ali, Fiona Price-Kuehne, Charles G Mackworth-Young

Department of Rheumatology, Charing Cross Hospital, London, UK

Objectives: To evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of tocilizumab (TCZ) in clinical patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) refractory to synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, anti-tumor necrosis factor agents, and B-cell depletion therapy with rituximab (RTX).

Methods: We conducted a single-center retrospective study of 22 patients with RA treated with TCZ. We collected data including demographics and medication histories. We recorded clinical parameters including tender joint counts and swollen joint counts, and laboratory parameters including inflammatory makers and lipid profiles over regular intervals of TCZ treatment.

Results: In all, 22 patients with RA were included, 20 of whom were female. The median age at the first dose of TCZ was 62 years (range: 35–75 years). The mean duration of the disease from diagnosis with RA to May 2015 was 15.7 years (range: 6–30 years). A total of 15 out of 22 patients remained on TCZ at the end of the study, and in all, there was an improvement in markers of disease activity following initiating TCZ. The effect was sustained for a mean of 35 months (SD ±15.5 months, range: 9–72 months). Of the 17 patients who failed to respond to RTX previously, 12 patients remained on TCZ. In all, eight out of 22 patients developed adverse events, five of whom discontinued TCZ. In contrast to previously documented short-term data, TCZ did not result in a statistically significant (P<0.05) long-term deterioration in lipid profile for any of the lipid parameters measured in our cohort (mean ± SD at initiation of TCZ to most recent follow-up: total cholesterol 5.25±1.05 to 5.28±0.77 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein 1.72±0.54 to 1.67±0.43 mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein 3.05±0.98 to 2.98±0.81 mmol/L, and cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein ratio 3.41±1.23 to 3.40±1.22).

Conclusion: The efficacy of TCZ in patients with RA refractory to disease-modifying drugs, including anti-tumor necrosis factor blockade and RTX, is sustained over 3 years. TCZ confers a good safety profile in the long term even in patients who previously developed adverse events to other rheumatic drugs. In the long run, there is no statistically significant deterioration in lipid profile during treatment with TCZ.

Keywords: tocilizumab, rheumatoid arthritis, refractory rheumatoid, long term, efficacy, safety, tolerability

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory autoimmune process, and the dysregulated overproduction of interleukin-6 (IL-6) plays an important role in its pathogenesis. Tocilizumab (TCZ) is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the IL-6 receptor and is recommended for use in RA.1

TCZ efficacy in the treatment of RA that has failed to respond to synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (sDMARDs), such as methotrexate, and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), such as anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, is well documented.2–4 Furthermore, there is evidence demonstrating good outcomes with TCZ in patients who have disease refractory to B-cell depletion with rituximab (RTX), a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20 B-cells, with up to 18 months’ follow-up.5,6 Long-term data, however, on the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of TCZ in RA that is refractory to sDMARDs, anti-TNF, and RTX are lacking.

Two major considerations when using TCZ in clinical practice are its immunosuppressive effects such as neutropenia and increased rate of infection,7–9 and the negative influence on lipid profile. It has been suggested that the rate of infection associated with TCZ is higher in clinical practice than in research populations, particularly in patients who have had a longer duration of disease and previous treatment with sDMARDs and bDMARDs.10 The relationship between adverse effects to previous disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and subsequently to TCZ has yet to be fully explored.11

Evidence suggests that in the first 6 weeks of treatment, TCZ adversely impacts low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels and fasting and postprandial triglyceride levels in patients with RA due to changes in hepatic LDL-receptor expression.12 Since RA alone is an independent risk factor for the development of atherosclerotic disease,13 any potential additional risk conferred by treatment is to be taken seriously. Again, however, long-term data regarding changes in patient lipid profiles following TCZ use are lacking.

We therefore set out to determine the long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of TCZ in patients with RA refractory to sDMARDs and bDMARDs, including anti-TNF therapy and RTX.

Methods

We performed a retrospective data collection on all patients diagnosed with RA, as defined by the American College of Rheumatology criteria, who had ever received TCZ as of May 1, 2015, in our department at Charing Cross Hospital (London, UK), an inner city teaching hospital.

We collected data including demographics, duration of diagnosis of RA, and staging of the disease. Any previous antirheumatic therapy and the reasons for failing previous sDMARDs and bDMARDs were identified. Follow-up from the first dose of TCZ and the number of cycles of TCZ received were determined.

We recorded clinical parameters including tender joint counts and swollen joint counts. We recorded laboratory parameters, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein, liver function tests, and lipid profiles with serum cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), LDL, and cholesterol/HDL ratio. Using the clinical parameters and the inflammatory markers, we calculated the 28 joint count ESR-based disease activity score (DAS-28-ESR) and used this to assess TCZ efficacy. All the parameters were recorded at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months after the first dose of TCZ and at the most recent follow-up appointment as of May 1, 2015.

Ongoing or historic use of lipid-lowering therapy was ascertained by reviewing patient’s medical records and corroborated by contacting patient’s general practitioners. We also recorded if any of the patients in our study had ever received a diagnosis of angina, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, or a cerebrovascular event, by the cutoff date of May 1, 2015.

We performed a statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism software Version 5. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used to assess significant differences (P<0.05) in parameters.

Advice was sought regarding ethical approval, and as no confidential attributable data were handled by researchers outside the clinical team, neither ethical approval nor specific patient consent was deemed necessary. There was no external funding for this work.

Results

Patient cohort

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the patient cohort and their antirheumatic treatment. In all, 22 patients with RA were included, 20 of whom were female. The median age at the first dose of TCZ was 62 years (mean ± standard deviation [SD] age 58.8±9.4 years, range: 35–75 years). In all, 20 patients had seropositive RA, defined as either a serum rheumatoid factor level >20 IU/mL or an anti-cyclic citrulinated peptide antibody level >5 units/mL (both of these represent the upper limit of the reference range for our laboratory). In all, 14 patients had erosive disease on the most recent radiography as defined by a radiology erosion score >0. The median duration from diagnosis with RA to May 1, 2015, was 15 years (mean ± SD duration 16±7.2 years, range: 6–30 years).

The mean follow-up from receiving the first dose of TCZ to May 2015 was 35 months, and the median was 28 months. A total of nine patients (41%) were followed up for more than 36 months after starting TCZ.

Of the 22 patients treated with TCZ, the majority (n=17) received it after failing anti-TNF and RTX treatment. Three patients received it as a first-line bDMARD after sDMARDs and two received it as a second-line biologic treatment after anti-TNF therapy.

The median number of DMARDs (both synthetic and biologic, excluding prednisolone) failed (due to intolerance or inadequate benefit) prior to the introduction of TCZ was 4.5 drugs. In all, 13 patients (59%) were on prednisolone orally at the time of starting TCZ and the dose did not exceed 10 mg daily.

Efficacy

Before the introduction of TCZ, all 22 patients had persistently high DAS-28-ESR (DAS-28-ESR >5.1, mean ± SD 6.9±1.7, Figure 1) despite trying at least two sDMARDs. All patients showed a reduction from baseline in the number of swollen and tender joints (Figure 1A and 1B, respectively). At the most recent follow-up, TCZ therapy was associated with reduced levels of ESR from 37.5±24.3 mm/h at baseline to 10.7±6.5mm/h, and C-reactive protein from 23.6±35.5 to 1.1±1.8 mg/L.

In all, 15 patients remained on TCZ at the end of the study (May 2015, mean follow-up 35 months), eight of whom were followed up for more than 36 months. In these 15 patients, there was a significant reduction in baseline DAS-28-ESR from 6.9±1.7 to 2.7±0.9 (mean ± SD). In all, nine (60%) were good responders according to European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria (DAS-28-ESR <3.2) and six (40%) were moderate responders (DAS-28-ESR between 3.2 and 5.1).

Upon initiating TCZ, all patients in the group were already receiving at least one other DMARD (Table 1). However, following treatment with TCZ, five patients successfully achieved disease control on TCZ monotherapy. In addition, nine patients were being treated with oral prednisolone at the starting (mean dose of 6.4 mg daily, median 5 mg), of which four were able to discontinue the steroids. The average dose of daily prednisolone for the remaining five patients following TCZ treatment was 3.3 mg daily (median 5 mg).

Previous therapy with bDMARDs

A total of 17 patients in our study group were defined as having anti-TNF- and RTX-refractory disease. The median interval between the last dose of RTX and the first dose of TCZ was 14 months (range: 4–32 months). Ten patients received only one cycle of RTX (2×1 g RTX, given 1–2 weeks apart) and seven patients received more than one.

Figure 2 summarizes the retention of TCZ following RTX therapy. In all, 14 out of 17 patients (82.4%) discontinued RTX due to inefficacy. Of these 14 patients, five (35.7%) also later discontinued TCZ – two (40%) due to inefficacy and three (60%) due to intolerance. The remaining nine (64.3%) continued on TCZ treatment. three patients were intolerant to RTX and all three (100%) remained on TCZ.

Safety and tolerability

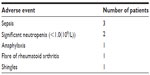

In all, eight out of 22 (36.4%) patients experienced an adverse reaction to TCZ (Table 2).

| Table 2 Adverse events experienced on tocilizumab and the number of patients for each adverse event, in order of frequency |

Of these eight patients, five discontinued the treatment: three after the first dose and two after the second dose. One patient developed anaphylaxis following the first dose, and three patients experienced significant sepsis, including discitis, urinary tract sepsis complicating diverticulitis, and chest sepsis. The patient who developed diverticulitis had been on TCZ for 57 months.

In all, three out of these eight patients continued TCZ: one after developing shingles and two after an episode of neutropenia (white cell count <1.0×109/L). For two patients, the frequency of treatment administration was reduced from monthly to 6 weeks, and for the third, the dose was reduced from 8 to 4 mg/kg.

Two patients developed neutropenia: one of them had a history of methotrexate-associated neutropenia; however, neither had developed neutropenia after treatment with RTX. Two patients who had discontinued RTX due to neutropenia continued on TCZ with no significant side effects.

All patients underwent 3 months monitoring of liver function tests according to our standard guidelines with the intention of stopping or modifying TCZ therapy if the alanine aminotransferase rose to greater than twice the upper limit of the reference range. This did not occur in any of our patients (data not shown).

Lipid profile and cardiovascular events

Total serum cholesterol levels, HDL and LDL levels, and cholesterol/HDL ratios were analyzed at 3, 12, 24, and 36 months, and at the most recent follow-up during TCZ treatment. One patient was on lipid-lowering therapy (ezetimibe) before commencing TCZ and was therefore excluded from this analysis. Four patients discontinued TCZ within 6 months and were also excluded.

Six out of the remaining 17 patients (35.3%) were started on lipid-lowering therapy at a median of 13 months (range: 1–26 months) after the first dose of TCZ (four received simvastatin and two atorvastatin). The reason for starting lipid-lowering therapy in these patients was primary prophylaxis in two patients; however, no cause could be determined in four patients. Among the eleven remaining patients not on lipid-lowering therapy, there was a trend to an increase in mean LDL and cholesterol/HDL ratio in the first 3 months after TCZ was initiated, although this did not reach statistical significance of P<0.05. Overall, there was no significant change in any of the lipid parameters at any time point (Figure 3). If patients who had started lipid-lowering therapy were included in the analysis, there was still no statistically significant change in lipid profile compared to baseline in the long run (data not shown).

At the most recent follow-up, none of the patients had been diagnosed with a transient ischemic attack or stroke. One patient had had a myocardial infarction and had undergone coronary bypass surgery and femoral artery surgery; however, these events had preceded the commencement of TCZ.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the efficacy of TCZ in patients with RA refractory to sDMARDs and bDMARDs, including TNF blockade and RTX, is sustained over 3 years. It also shows a good safety profile and stable lipid profile over this period. This is longer than previously documented follow-up in the study.5,6

Our single-center observational study shows that in the majority of patients who have failed to respond to previous sDMARDs and bDMARDs, including adequate B-cell depletion, there is good long-term efficacy for TCZ at the most recent follow-up (mean 35 months). All patients who remained on TCZ achieved at least a moderate response (DAS-28-ESR <5.1) according to EULAR criteria, with 60% of patients achieving a good response (DAS-28-ESR <3.2). This is consistent with previously documented data regarding the use of TCZ following sDMARDs and anti-TNF-refractory RA.2,4

Our data also demonstrate sustained efficacy of TCZ in RTX-refractory RA beyond the previously documented follow-up of <2 years.5 TCZ treatment was associated with withdrawal of other DMARDs and prednisolone such that TCZ monotherapy was achieved in five patients. This is consistent with the evidence suggesting a steroid sparing effect of TCZ treatment.14

In our cohort, only a minority of patients developed significant side effects requiring cessation of treatment. The side effect profile was similar to that described in the STREAM trial.15 Neutropenia remains a clinical concern,9 and two patients developed this in our study. Overall, there appears to be no clear relationship between the development of an adverse event on TCZ, including infections, and a history of adverse events on previous DMARDs. Therefore, our long-term data are suggestive of a good safety profile of TCZ.

The lipid profile analysis demonstrates a tendency toward a deteriorating lipid profile in the first 3 months of starting TCZ, which is consistent with the existing evidence.12 However, there was no statistically significant difference in lipid profile in the long run compared to baseline (Figure 3). Moreover, in this study, only a minority of patients were commenced on lipid-lowering therapy. On the one hand, this may suggest that TCZ overall does not negatively impact the lipid profile of patients’ long term as previously believed. On the other hand, in order to confirm this, it would be helpful to analyze patient lipid profiles without the bias of lipid-lowering therapy. Still, even if those patients on lipid therapy were included in the analysis, a change in lipid profile did not achieve statistical significance, indicating that lipid-lowering therapy in these patients was successful.

Crucially, none of the patients in our cohort developed significant cardiovascular events while on TCZ. This may be related to the known correlation between improved DAS-28 and reduced cardiovascular risk described by Rao et al.16 However, our study was not of adequate size, design, or length to assess this fully.

In this study, only two patients discontinued TCZ due to inefficacy. However, predicting responsiveness to TCZ can be challenging. One earlier study found variable cytokine profiles of serum and synovial aspirates in RA patients and concluded that this might influence response to biologic therapy.17 Another postulated that baseline serum IL-6 is a potential biomarker to predict responsiveness to TCZ.18 Increased synovial IL-6 levels in a patient with anti-TNF and RTX-refractory RA were suggested to predict a good response to TCZ.3 Finally, Das et al suggested that in patients with RTX-refractory RA, persistently high serum IL-6 concentrations following adequate B-cell depletion may favor IL-6 targeted therapy rather than T-cell co-stimulation blockade.5 Further research is needed to establish the exact mechanism of response or resistance to TCZ.

In all, 90% of our patients were female, and the average age at the onset of TCZ treatment was 62 years. These demographic characteristics are comparable to those documented in the study: 79% females and a mean age of 57 years.19 The high proportion of females could be a sampling effect due the size of our sample.

Other limitations to our study include it being single center, observational, and with a relatively small number of patients. Larger, multi-center cohort studies would be needed to confirm long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of TCZ in refractory RA.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Mrs Angela Smith for her help with maintaining a record of patients receiving TCZ at our center.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

NICE [webpage on the Internet]. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence: Tocilizumab for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis (Rapid Review of Technology Appraisal Guidance 198). 2012. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta247 2012. Accessed February 26, 2015. | |

Yazici Y, Curtis J, Ince A, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis and a previous inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: the ROSE study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(2):198–205. | |

Wright H, Mewar D, Bucknall R, Edwards S, Moots R. Synovial fluid IL-6 concentrations associated with positive response to tocilizumab in an RA patient with failed response to anti-TNF and rituximab. Rheumatology. 2015;54(4):743–744. | |

Emery P, Keystone R, Tony H, et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1516–1523. | |

Das S, Vital E, Horton S, et al. Abatacept or tocilizumab after rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis? An exploratory study suggests non-response to rituximab is associated with persistently high IL-6 and better clinical response to IL-6 blocking therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(5):909–912. | |

Addimando O, Possemato N, Macchioni P, Salvarani C. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in refractory rheumatoid arthritis: a real life cohort from a single centre. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(4):460–464. | |

Besada E, Koldingsnes W, Nossent J. Characteristics of late onset neutropenia in rheumatologic patients treated with rituximab: a case review analysis from a single center. Q J Med. 2012;105(6):545–550. | |

Sakai R, Cho S, Nanki T, Watanabe K, Yamazaki H. Head-to-head comparison of the safety of tocilizumab and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis patients (RA) in clinical practice: results from the registry of Japanese RA patients on biologics for long-term safety (REAL) registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):74. | |

Wright H, Cross A, Edwards S, Moots R. Effects of IL-6 and IL-6 blockade on neutrophil function in vitro and in vivo. Rheumatology. 2014;53(7):1321–1331. | |

Lang V, Englbrecht M, Rech J, et al. Risk of infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tocilizumab. Rheumatology. 2012;51(5):852–857. | |

Shovman O, Schoenfeld Y, Langevitz P. Tocilizumab-induced neutropenia in rheumatoid arthritis patients with previous history of neutropenia: case series and review of literature. Immunol Res. 2015;61(1):164–168. | |

Strang A, Bisoendial R, Kootte R, et al. Pro-atherogenic lipid changes and decreased hepatic LDL receptor expression by tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis. 2013;229(1):174–181. | |

Barbhaiya M, Soloman D. Rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease: an update on treatment issues. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25(3):317–324. | |

Fortunet C, Pers Y, Lambert J, et al. Tocilizumab induces corticosteroid sparing in rheumatoid arthritis patients in clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2015;54(4):672–677. | |

Nishimoto N, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, Azuma J. Long-term safety and efficacy of tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, in monotherapy, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (the STREAM study): evidence of safety and efficacy in a 5-year extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1580–1584. | |

Rao V, Pavlov A, Klearman M, et al. An evaluation of risk factors for major adverse cardiovascular events during tocilizumab therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(2):372–380. | |

Wright H, Bucknall R, Moots R, Edwards S. Analysis of SF and plasma cytokines provides insights into the mechanisms of inflammatory arthritis and may predict response to therapy. Rheumatology. 2012;51(3):451–459. | |

Shimamoto K, Ito T, Ozaki Y, et al. Serum interleukin 6 before and after therapy with tocilizumab is a principal biomarker in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(7):1074–1081. | |

Sokka T, Toloza S, Cutolo M, et al. Women, men, and rheumatoid arthritis: analyses of disease activity, disease characteristics, and treatments in the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(1):R7. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.