Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Relationship Between Work-to-Family Conflict and Conspicuous Consumption: An Identity Theory Perspective

Authors Gong Y, Chen C , Tang X, Xiao J

Received 31 August 2022

Accepted for publication 24 December 2022

Published 6 January 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 39—56

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S388190

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Yanping Gong,1 Chunyan Chen,1,2 Xiuyuan Tang,3 Jun Xiao1

1School of Business, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Business Administration, Hunan University of Finance and Economics, Changsha, Hunan, People’s Republic of China; 3School of Business, Hunan Women’s University, Changsha, Hunan, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xiuyuan Tang, School of Business, Hunan Women’s University, Changsha, Hunan, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The adverse effects of work-to-family conflict in occupational health fields have been widely concerned. However, we do not yet know whether and how work-to-family conflict affects people’s consumption behavior. This study used identity theory as the conceptual framework to test the hidden link between work-to-family conflict and conspicuous consumption, the possible underlying mechanism of status anxiety, and the boundary condition of work-family centrality.

Methods: We conducted two quantitative studies to test the hypotheses. Study 1 used a cross-sectional survey (N = 486) to test the relationship between work-to-family conflict and conspicuous consumption and the mechanism of the relationship. Study 2 used a 10-day daily diary survey (Nbetween = 100, Nwithin = 776) to duplicate the results of Study 1 and further test the moderating effect of work-family centrality.

Results: We found that work-to-family conflict was positively related to conspicuous consumption, and this relationship was mediated by increased status anxiety. Moreover, this mediating effect was more substantial for employees with lower work-family centrality.

Conclusion: This research is the first to link work-to-family conflict and conspicuous consumption theoretically and empirically. The findings supported identity theory, adding new knowledge to the consequences of work-to-family conflict and contributing to organizations’ prevention and intervention programs on behavioral health issues in work-family conflict.

Keywords: work-to-family conflict, status anxiety, work-family centrality, conspicuous consumption, identity theory, daily diary study

Introduction

Work and family are two critical components of an employee’s life,1 but balancing the demands of work and family can be difficult for them in the current society.2,3 With more and more wives going to work, husbands are also asked to take on more family responsibilities.4 Work-family conflict among dual-earner families is getting severe.5,6 Especially in fast-developing China, people have to work hard to keep up with social development.7 It is more prevalent for work to interfere with family than for family to interfere with work.8 Even during the time spent with family, people are often asked to deal with work issues. Work-to-family conflict have become more ubiquitous than ever.

Work-to-family conflict (WFC) arises when the demands from work interfere with the fulfillment of family obligations.9 Due to its prevalence and the substantial influence it can have on people’s quality of work and life,4 there has been considerable academic research on the topic of WFC.10,11 Earlier studies on the consequence of WFC mainly focused on employees’ mental health (eg, general stress and depression,12,13 burnout,1,14 emotional intelligence, and self-efficacy)15 and physical health (eg, coronary heart disease,16 hypertension).17 Recently, research on the impact of WFC has also begun to spill over into the behavioral domain, such as aggressive behavior,18 procrastination behavior,19 and workplace deviance behavior.20 However, these studies have only focused on WFC’s effects on organizational behavior. The effects of WFC on the conduct of individuals outside of organizations remain uncertain.

It is important to note that each employee serves as a person within the company and a consumer in the consumer market. Although some studies have found that work status will affect employees’ consumption behavior,21–23 no studies have focused on the relationship between employees’ WFC and their consumption behavior. Based on previous studies, this research is for the first to link WFC with employees’ consumption behavior. Notably, according to identity theory,24,25 we are specifically interested in the impact of WFC on conspicuous consumption. Employees with WFC have status anxiety because their work status or family status is often unsatisfactory.24–26 This status-related dissatisfaction leads to people engaging in conspicuous consumption to compensate for it.27–30 Therefore, this paper aims to explore the working mechanism by which WFC influences conspicuous consumption through status anxiety.

This research includes two studies, the initial validation of the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption was first conducted by a questionnaire study. However, the demands of work and family that each individual faces daily are variable, leading to changes in WFC.31,32 In addition, the tendency to conspicuous consumption is not constant and can be triggered by immediate stimuli.33 Previous research has noted that between-person relationships cannot extrapolate to within-person when the variables are not stable.34 The findings of the cross-sectional questionnaire study are related to between-person relationships and reflect more stable and global construction.5 In contrast, diary data allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of everyday WFC perceptions. The findings from these two kinds of data may be considerably different due to the contextual effects.35,36 Besides, a daily diary study can improve the ecological validity and reduce recall bias.5,32,37 The applicability of the daily diary study technique has been widely utilized in work-family interface-related research.5,38,39 So we followed the questionnaire study with a 10-day diary method study, which was used to capture subtle changes in individuals’ daily WFC, to discover the within-person relationships.

As an extension of Study 1, Study 2 also included work-family centrality as a moderating variable of the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption to examine whether the daily association between WFC and conspicuous consumption is influenced by stable work-family centrality. Work-family centrality is a value judgment of the relative importance of work and family that influences the association between work-family conflict and outcome factors.38,40,41 It is relatively stable and does not change over time in the short term.38 Therefore, the two studies’ findings can verify the association between WFC and conspicuous consumption, mediation processes, and boundary conditions, taking into account the between-person and within-person levels.

Since WFC is highly prevalent,10 exploring the effects of WFC on consumption behavior is not a trivial matter, as it helps advance our overall picture of the possible aftereffects of WFC. Theoretically, our contribution to the study of the work-family interface is to extend the effect of WFC to extra-organizational behavior for the first time. Moreover, consumption behavior and general wellbeing are closely related.42,43 Studying the impact of WFC on conspicuous consumption has important implications for practice. Our findings can assist organizations in gaining a more thorough understanding of the potential repercussions of their employees’ WFC to intervene and advise them. It can also serve as a theoretical foundation for employees to scrutinize and comprehend their consumption patterns.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Work-to-Family Conflict and Conspicuous Consumption

People with WFC frequently find it challenging to meet their own and others’ expectations. Dual-earner family members have two crucial identities simultaneously: employee and family member. In the study of “identity”, identity theory is one of the most commonly used theories.24,44–48 Identity theory suggests that people’s identities are imbued with different expectations and meanings.25 Individuals, roles, and groups/societies form the three bases of identity.49 One is expected or supposed to be able to perform well in work tasks or performance appraisals in employee identity and fulfill family obligations timely in a family member’s identity. Therefore, work-family balance is important for the ought self of a dual-earner family member.

Besides, balancing work and family is a fundamental desire for individuals.50 It satisfies the basic needs of individuals’ competence and relatedness, which bring them self-esteem, a sense of power, and control.51 However, balancing work and family is not easy to achieve. People have limited time, energy, and competencies.52–54 Spending too many resources in one domain can affect their performance in the other.52 A meta-analysis showed that WFC might lead to poor employee performance in the family and work domains.55,56 Employees may question their identity as “good” family members and workers.52,57

It is repugnant for people to feel insecure about their status or identity. People have an innate drive to reduce this kind of self-discrepancy.58 Discrepancies between one’s actual self and ought self can cause people to feel threatened, worried, and anxious about their status.28 Among the strategies people use to restore status, consumption behaviors were among the first to be shown by researchers.59–61 These consumption behaviors are not functional but rather compensatory. Several studies have pointed out that people will likely engage in compensatory consumption when they become aware of status insecurity.62–65 As a ubiquitous form of compensatory consumption, conspicuous consumption is often used to alleviate self-discrepancies related to status, power, and control.28–30 This consumption behavior does not directly eliminate the issues, but it can successfully comfort oneself.66 Research pointed out that people consume conspicuously when their status is threatened or they are not successful enough.

In sum, WFC can cause people to underperform at work or home, leaving their desire for work-family balance dashed and their basic needs for relationships and competence unfulfilled.51,55,56 Thus, WFC is an essential trigger for perceived status or identity insecurity and discrepancies, leading to conspicuous consumption.27,67 Therefore, we hypothesize that WFC can be an important antecedent to conspicuous consumption.

Mediating Role of Status Anxiety

WFC can affect people’s psychology because it impacts their self-verification and creates identity insecurity.12,13 Identity theory suggests that people will perform self-verification by comparing their authentic and socially-expected selves for important identities.24,25 Successful self-verification indicates that people meet society’s expectations successfully. The discrepancies between their actual-self and ought-self are negligible, and they can gain status and respect accordingly.24,25 Conversely, failure in self-verification indicates that people fail to be the ought-self, predicting great self-discrepancies. Status anxiety refers to worry about failing to meet the ideals of success.24–26 People are always anxious about their status, especially when they “concerned about being devalued”.68 In the two most important domains of work and family, according to identity theory,24,25 people complete their self-verification by performing “good” both in the work and family domain, that is, acquiring work-family balance. They are considered to have status and value when they can fulfill both their work assignments and family obligations. However, WFC breaks the balance, making people’s self-verification fail and creating self-discrepancies. Discrepancies between actual-self and ought-self can induce agitation-related emotions.28 In this context, people may be trapped in status anxiety.

When people perceive self-discrepancies in status, they may use compensatory consumption to resolve those discrepancies.27,28,69,70 Many studies have shown that people view conspicuous consumption as psychological comfort and compensation for unmet needs.27,30,66 Acquiring status is one of the main motivations for consumption behavior.71 When a person perceives that they are about to lose their status or are dissatisfied with the status they have gained, they use status conspicuous products to “show off” their status as if they are successful.62,64,72 Hence, individuals with a sense of self- discrepancy in status tend to adopt more conspicuous consumption to reduce the discrepancy and protect themselves from threats symbolically.

According to identity theory, WFC could create status anxiety by undermining people’s self-verification processes and creating self-discrepancies.24,25 Taken together, when employees experience WFC, they may be stuck in status anxiety and engage in conspicuous consumption to gain transient alleviation of anxiety.30,60,66,73 In other words, status anxiety is a mechanism behind the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption.

Moderating Role of Work-Family Centrality

The mediating effect of status anxiety in the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption may vary with individual traits. It is significant to understand the boundary conditions of this mechanism of action for organizations to adopt corresponding interventions. Work-family centrality is one of the most critical personal traits in work-family interface research,38,40,41 which refers to the relative importance of work and family roles.40 High work-family centrality means that people value their work more than their family. People put more effort into a more salient identity and engage in more behaviors related to that identity because high performance in that identity is more satisfactory.25,74 Therefore, individuals with high work-family centrality are willing to spend more resources (time, energy, and competencies) at work. Accordingly, success in the work domain is more meaningful for their self-verification and more favorable for self-actualization.

Previous research figured out that work-family centrality can attenuate the negative relationship between WFC and employees’ attitudes toward the organization,40 attenuate the positive relationship between job meaning and employee emotional commitment,41 and exacerbate the positive relationship between private smartphone use at work and employee emotional exhaustion.38 These findings suggest that employees’ responses to the work situation will vary by work-family centrality. Employees with high work-family centrality are more likely to tolerate the conflict caused by work (vs family) and accept the poor performance in the family (vs work) in terms of attributions. They tend to blame WFC on the family role.40 This attribution could lead to a weaker effect of WFC on work-related outcomes.40 Although performance in the family domain might be obstructed,9 there would be little impact on self-verification because poor performance in a less central role (ie, family) poses less threat to the self.75 The success of self-verification of employees with high work-family centrality depends mainly on their performance at work, not on whether they fulfill their family obligations. As a result, even if their work interferes with the family, they may not be bothered much.

Hence, employees with high work-family centrality do not have strong negative emotions when they cannot obtain the work-family balance due to WFC. That is, WFC cannot impact their self-verification much and does not lead to severe status anxiety.25 Conversely, employees with low work-family centrality will value the family’s demands more, so it is hard for them to tolerate work interference with the family. The poor performance in the family domain is fatal to their self-verification of family membership and predicts high levels of status anxiety in the context of WFC. As status anxiety is increased, so will the individual’s propensity for conspicuous consumption.

Drawing on the previous inferences and evidence to date, the effect of WFC on employees’ conspicuous consumption through increased status anxiety varies with their work-family centrality. To sum up, the full conceptual model we are testing includes mediation and moderation. Based on identity theory,24,25 WFC frustrates the self-verification process and generates status anxiety, leading to conspicuous consumption. Work-family centrality moderates the first link of this process. Thus, the hypotheses were proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Work-to-family conflict is positively related to conspicuous consumption. Hypothesis 2: Status anxiety mediates the relationship between work-to-family conflict and conspicuous consumption. Hypothesis 3: Work-family centrality moderates the relationship between employees’ work-to-family conflict and status anxiety. Specifically, the positive relationship is stronger for employees with lower work-family centrality. Hypothesis 4: The mediating effect of status anxiety in the relationship between work-to-family conflict and conspicuous consumption will be moderated by work-family centrality. Specifically, the first link in this mediation process is more substantial for employees with low work-family centrality.

The Present Study

The current research had three purposes. Firstly, to explore the potential association between WFC and conspicuous consumption. Secondly, to explore the mediating role of status anxiety in this relationship. Thirdly, to investigate the moderating role of work-family centrality in this process. The contributions of this research are fourfold. Firstly, the present study examined the effect of WFC on employees’ consumption behavior based on identity theory, which provides a new theoretical perspective for the research of the work-family interface. Secondly, this is the first study to link WFC and consumption behavior together, extending WFC’s behavioral health-related outcomes. Thirdly, our study contributes to the extant research on the antecedents of status anxiety. This study figured out that the ubiquitous WFC could also be a source of self- discrepancy in inducing status anxiety. Finally, our study echoes previous researchers’ calls to explore the moderating role of work-family centrality in WFC contexts.76 The results help organizations design interventions to decrease employees’ status anxiety and subsequent irrational consumption behavior. To achieve these purposes, we will conduct a cross-sectional study to preliminarily explore the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption and the mediating mechanism. Furtherly, we conducted a 10-day diary study to obtain a more precise relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption and the moderating role of work-family centrality in the relationship. The full conceptual model was shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 The hypothesized moderated mediation model. |

Study 1: Questionnaire Study

A cross-sectional study was used in Study 1, which is generally used in studies on work-family interface.5 In Study 1, we tested two Hypotheses: 1. the effect of WFC on conspicuous consumption (Hypothesis 1); 2. the mediating role of status anxiety in the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption (Hypothesis 2).

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

The questionnaires for Study 1 were distributed by way of junior high school students taking them home to their parents. The following day, the students returned to school with the completed questionnaires and gave them to the researcher. Participants received assurances that all information provided would be treated in strict confidence and that only the researchers would see the completed questionnaires. The local ethics committee gave its approval to the study. All participants gave informed consent and were not paid. We began the survey with questions about employment status and asked for their contact information (cell phone number or email address) at the end of the questionnaire for the follow-up study. Only questionnaires from full-time employees were deemed valid. Of the total 756 questionnaires, 486 were valid. Of the 486 employees in the final sample, about half (50.4%) were males. The mean age of all the participants was 41.04 years (SD = 4.34). The educational backgrounds of the participants ranged from 8th grade to graduate school, with 46.5% having completed junior college and above. Most of the sample had worked for more than three years (78.6%). 82.3% had an annual household income of more than 100,000 RMB (approximately US$14,152).

Measures

A translation and back-translation method was applied to translate the English-language scales into Chinese in both study 1 and study 2. The second and third authors first translated the English scales into Chinese, and we invited two bilingual Ph.D. students to translate them into English. Four students compared the discrepancies in each item to ensure the meaning of items in the Chinese scale was as close as possible to the original ones.

WFC was estimated using a subscale of the Work-family Conflict Scale developed by Carlson et al.77 This scale includes two aspects of the work-family conflict: work-to-family conflict (WFC) and family-to-work conflict (FWC). Compared with FWC, WFC has been demonstrated to be more widespread and to have a more significant influence on an individual’s life.8,78 Hence, we only focused on the WFC aspect. Three dimensions, time-based WFC, strain-based WFC, and behavior-based WFC, were used to estimate the generic WFC. Every dimension was assessed using three items. A five-point scale was used for rating the items by the participants. An example item is “My job takes me away from my family campaigns”. 1 represented “totally disagree”, and 5 represented “totally agree”. The scores of all nine items were averaged. The higher the average score is, the higher the WFC. The current scale’s reliability and validity have been found suitable in the context of China.79,80 The Cronbach’s alpha in the present study is 0.82.

Status anxiety was measured using the six-item Status Anxiety Scale developed in the Chinese context by Wang and Zhu.81 Example items are “I get upset at the thought of my social status now” and “I feel comfortable with my present social status” (reverse coded). Items were scored on a five-point scale (1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree). Answers across the six items were averaged. The higher the score, the higher the level of status anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.81 in the original study. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.70.

The eighteen-item Conspicuous Consumption Scale developed by Marcoux et al82 was used to assess five dimensions of conspicuous consumption: materialistic hedonism, affiliations or dissociations, status symbols, interpersonal intermediaries, and ostentations. In this study, we removed the word “western” from the original items, as many well-known Chinese brands also have the properties of conspicuousness. For example, in the item “People buy western products to enhance their image”, the phrase “western products” was simplified to “products”. The participants used a seven-point scale to answer each item, where 1 represented “totally disagree” and 7 represented “totally agree”. The scores of the eighteen items were averaged. The final score represents the willingness of the participants to adopt conspicuous consumption. The current scale’s reliability and validity have been found good in the context of China.83 The Cronbach alpha of this scale in the present study is 0.96.

Control variable. Four variables were controlled in Study 1. Gender (1 = male; 2 = female) was controlled because men were less interested in conspicuous consumption than women.84 Education level (1 represented “high school and below”; 4 represented “master’s level and above”) was controlled because this characteristic could contribute to the social hierarchy, which is associated with status anxiety.85 Work tenure (1 represented “less than one year”; 3 represented “more than three years”) was controlled because it could be regarded as a resource to alleviate the work-family conflict.86 Age was controlled because work-family centrality differed significantly among the different age groups.87 Finally, as income was associated with employees’ status anxiety and conspicuous consumption,88,89 annual household income was also included as a control variable (1= $7070 and below; 6= $70,700 and above). Except age, all the other control variables were transformed into dummy variables before data analysis.

Analysis Strategy

In Study 1, The hypotheses were tested with multiple linear regression by SPSS 25.0 and the SPSS PROCESS macros,90 which have been widely applied in recent studies.91–93 Bootstrapping was employed to examine the significance of the direct and the moderate effects. Specifically, Hypothesis 1 was examined via multiple linear regression. Hypothesis 2 was examined via SPSS PROCESS Model 4. 5000 iterations of bootstraps generated the bootstrap-based 95% confidence intervals with bias correction for simple effects.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations of the variables. WFC was both positively linked with conspicuous consumption (r = 0.20, p < 0.001), which preliminarily supported Hypothesis 1.

|

Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Research Variables in Study 1 |

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) are used to assess the discriminant validity of these measures and eliminate the concern of the common source bias of data in this study. We used AMOS 24 software to compare two measurement models: the one-factor model and the hypothesized ten-factor model encompassing the three dimensions of WFC, status anxiety, five dimensions of conspicuous consumption, and the work-to-family centrality. In the one-factor model, all the items are loaded onto a single factor. For the hypothesized ten-factor model, the items are loaded onto their hypothetical constructs. The results show that the hypothesized ten-factor model (χ2/df = 3.37; CFI = 0.88; NFI = 0.84; IFI = 0.88; RMSEA = 0.07) fits the data well and better than the one-factor model (χ2/df = 10.21; CFI = 0.51; NFI = 0.49; IFI = 0.51; RMSEA = 0.14), supporting the discriminant validity.

Hypothesis Testing

Table 2 illustrates the regression results for direct effects and indirect effects. Hypothesis 1 predicted that WFC would positively correlate with conspicuous consumption. The results in Table 2 (M2) showed that employees’ WFC was positively related to their willingness to conspicuous consumption (B = 0.289, SE= 0.064, p < 0.001), thus Hypothesis 1 was supported.

|

Table 2 Regression Results for Direct and Indirect Effects in Study 1 |

Hypothesis 2 assumed that status anxiety mediated the effect of WFC on conspicuous consumption. Table 2 (M1) showed that the relationship between WFC and status anxiety is significantly positive (B = 0.247, SE = 0.036, p < 0.001). The relationship between status anxiety and conspicuous consumption is significantly positive (M3, B = 0.279, SE = 0.081, p < 0.001). Moreover, the simple mediating effect of status anxiety was significant (B = 0.069, 95% CI = [0.028, 0.113]). The direct effect of WFC on conspicuous consumption was also significant (B = 0.220, 95% CI = [0.089, 0.351]). The indirect mediation effect was 23.88% of the total effect. The path coefficient is shown in Figure 2. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

|

Figure 2 Mediation model test for Study 1. Note: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. |

Study 2: Daily Diary Study

WFC may vary slightly across workdays,31 and its consequences may vary accordingly.32 Similarly, conspicuous consumption behavior could be driven by immediate stimulus (such as winning a competition).33 Therefore, it is necessary to use a daily diary approach to capture the dynamics of WFC and conspicuous consumption and examine the relationship between them. The daily diary methodology has been widely used in recent management and psychology research.39,94–97 It allows assessing dynamic processes in everyday life, detecting small changes, improving ecological validity, and reducing recall bias.5,32,37 Thus, Study 2 used a daily diary methodology to reach the three objectives: 1. replicate the results of Study 1 by using diary study data with repeated measurements over ten consecutive working days; 2. examine the moderating role of stable work-family centrality between daily WFC and daily status anxiety (Hypothesis 3); 3. test the integrative moderated mediation model (Hypothesis 4).

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

213 of the subjects in Study 1 left their contact information. After the researchers contacted them through these contacts and explained the purpose and procedures of Study 2, 128 were willing to participate in the daily diary study. Participants complete questionnaires on ten consecutive days and are used to repeatedly measure their daily WFC, status anxiety, and tendency to conspicuous consumption. A WeChat group was established to communicate with the participants and distribute the daily questionnaire. Each night at 9 pm, the researcher posted a link to the daily questionnaire in the WeChat group so that the participants could fill it out before going to bed.14 Participants received the link to our daily questionnaire for ten consecutive working days. Specifically, we explained the purpose of the study, informed all participants of the study procedures, and obtained their informed consent before the study.

The demographic information and work-family centrality was between-person variables and only measured once on a weekend evening because they do not change over short periods.38,98 Of the 128 participants, 28 had less than five days of cumulative questionnaires, so their data were excluded. In the end, the 100 participants filled out 776 questionnaires for an average of 7.76 days per participant. These samples are sufficient because they could meet the sample requirements for diary studies as proposed by Scherbaum and Ferreter.99 Of the 100 participants, 42 were male, the mean age was 36.47 years (SD = 8.07), and almost all participants had an education level above junior college (94.0%). Most of the sample had worked for more than three years (78.6%). 68.0% had an annual household income of more than 100,000 RMB (approximately US$14,152).

Measures

Diary Questionnaires (Within-Person Variables)

We included “today” in each item description for the daily-level variable scales to accommodate the daily diary test.31 In addition, because the items in daily-level should be filled in the daily questionnaire for ten consecutive working days, we simplified the measurement scale to shorten the time for the participants to complete the questionnaire every day.100,101

Daily WFC was assessed using the three-item Work-family Conflict Scale from Netemeyer, Boles, and Mcmurrian102 and Hill103 and was revised to the daily level. The items were “To what extent does your work interfere with your family today?”, “To what extent does your work leave you feeling like you do not have enough time or energy for family matters today?” and “How much your work prevents you from doing something family-related today” (1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree). Answers across the three items were averaged. The higher the score, the higher the WFC. This scale has shown good reliability and validity in a recent Daily Diary study on WFC.104 The mean Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83 in this study.

Daily status anxiety was measured using the 5-item Status Anxiety Scale developed by Keshabyan and Day.105 The items were revised to adapt to the daily diary methodology by adding “today” in the item description. An example item was, “Today, I worry about my current low position”. Items were scored on a five-point scale (1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree). Answers across the five items were averaged. The higher the score, the higher the status anxiety. This scale has shown good reliability and validity in a recent study.106 The mean Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79 in this study.

Daily conspicuous consumption was measured by a scenario-based questionnaire. This approach has been extensively used in studies measuring the intention for conspicuous consumption.64,72,107 Participants were asked to choose between two pictures of a product. These products were selected from a pre-survey (188 working couples) of the top ten products that were perceived to be the most conspicuous. The products in the two pictures were identical, but the size and visibility of the brand logo were different. The size and visibility of the logos indicated the degree of conspicuousness.64,72,107 Specifically, participants were asked to imagine buying a high-end dress, hat, or shoes (which varied from day to day). Participants were then asked to score on a seven-point Likert scale. Pictures of these two products were placed on either side of the scale. On the left were those logos that were least visible or small in size, and on the right were those that were most visible or large. The higher the score, the greater the participant’s preference for conspicuous consumption. The product pictures used in this experiment were repeated every five days to exclude other confounding factors that might influence participants’ choices, such as product type.108

General Questionnaire (Between-Person Variables)

The demographic variables and work-family centrality variables were only measured once because they remained steady over a short period of time.38,98 The measurements were the same for the control variables (gender, age, education, tenure, income) as those in Study 1. Work-family centrality was assessed by a five-item Work-family Centrality Scale developed by Carr et al.40 A five-point scale was applied to answer each item by the participants (eg, “In my opinion, one should put work first rather than family first”); 1 indicated “totally disagree” and 5 indicated “totally agree”. The scores of the five items were averaged; the final scores represent the importance of work relative to the family. This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in the Chinese context.109,110 In Study 2, the mean Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83. The control variables in Study 2 include gender, age, education level, tenure, and income, as in Study 1. All the other control variables were transformed into dummy variables before data analysis except age.

Analysis Strategy

Multi-level Linear models (MLM) were employed to analyze the nested data. The multi-level data comprised within person (Level 1; Nwithin = 776 study occasions) nested in the between person (Level 2; Nbetween = 100 participants). Mplus 7.4 software was applied to analyze the multi-level data.111 Following Ohly et al94 suggestion, the predictors in the within-person level (WFC, status anxiety, conspicuous consumption) were centered on the group mean. The predictors in the between-person level (work-family centrality) were centered on the grand mean. The effects in the models were estimated based on the maximum likelihood method suggested by Preacher et al112,113 Demographic variables (ie, gender, age, education level, tenure, and annual household income) were controlled at the person level.

Results

To ascertain whether the data are required for multi-level analysis, we first looked at the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of the daily measured variables. The ICC shows the proportion of unexplained variation in the model that can be assigned to the grouping variable, relative to the total unexplained variation (within and between variance).114,115 The ICC values in Table 3 (ranges from 0.25 to 0.73) were greater than the suggested threshold of 0.059 for multi-level analysis,116 indicating the necessary of multilevel analysis.

|

Table 3 Means, Standard Deviations, Intra-Class Correlations, and Correlations Among Variables in Study 2 |

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations among variables in Study 2. The results in Table 3 showed that WFC was positively associated with conspicuous consumption in within-person level (r = 0.18, p < 0.001) and in between-person level (r = 0.24, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was preliminarily supported and the result of Study 1 was replicated.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

Before testing the hypotheses, we used Mplus 7.4 software to run TWO-LEVEL CFA analyses to assess the discriminant validity of these measurements and to eliminate concerns about common source bias in the questionnaire data in study 2. Work-family centrality was in the second level, WFC and status anxiety were in the first level, and these three variables were unidimensional. Conspicuous consumption (dependent variable) was not placed in the CFA model because it contained only one item. The CFA results show that the three-factor model (ie, WFC + status anxiety + work-family centrality) fits the data well (χ2/df = 2.60; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; SRMRwithin = 0.06; SRMRbetween = 0.05) and much better than the two-factor model collapsing the daily measured variable (WFC and status anxiety) into one factor (χ2/df = 11.78; CFI = 0.61; TLI = 0.51; SRMR within = 0.18; SRMR between = 0.19). These results supported the discriminant validity.

Hypothesis Testing

The hypotheses were put to the test across four MLMs, and the estimates were displayed in Table 4. Gender, age, education, tenure, and income were controlled for as between-person variables. The first model (M1) was used to test the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption (Hypothesis 1). In the within-person level, conspicuous consumption was regressed onto WFC. In the between-person level, conspicuous consumption was regressed onto controls. As shown in M1, the results supported the Hypothesis 1 that employees’ WFC was positive related with conspicuous consumption (B = 0.390, SE = 0.082, p < 0.001). Thus, these results replicate the findings in Study 1.

|

Table 4 Multilevel Estimates for Models Predicting Status Anxiety and Conspicuous Consumption |

The second model (M2) examined the mediating role of status anxiety in the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption (Hypothesis 2). In M2, gender, age, education, tenure, and income were controlled at the between-person level. At the within-person level, the regression coefficients of status anxiety were tested by including conspicuous consumption as the dependent variable while controlling for WFC. The results showed a significant positive relationship between status anxiety and conspicuous consumption (B = 0.498, SE = 0.169, p < 0.01). To further test the mediation effect, this study applied Monte Carlo sampling 1000 times, and the results showed that the mediation effect was 0.111 (SE = 0.039, p < 0.01, 95% CI= [0.047, 0.176]). Therefore, the mediation effect was significant. The path coefficient is shown in Figure 3. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported, and the result in study 1 was replicated.

|

Figure 3 Mediation model test for Study 2. Note: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. |

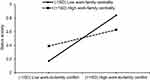

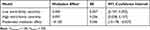

The third model (M3) examined the moderating role of centrality in the relationship between WFC and status anxiety (Hypothesis 3). Before the test, following Ohly et al94 suggestion, the predictors in the within-person level (ie, WFC) were centered on the group mean. The predictors in the between-person level (ie, work-family centrality) were centered on the grand mean. After the centrality treatments, the between-person variable (work-family centrality) was implemented as a predictor of the slope of the relationship between WFC and status anxiety. At the same time, gender, age, education, tenure, and income were controlled as between-person variables to conduct a cross-level moderating effect test. The results in M3 showed that the interaction effect of WFC and work-family centrality on status anxiety was significant (B = –0.108, SE = 0.041, p < 0.01). Then, to examine the interaction effect in more detail, a simple slope test was performed, followed by Preacher et al,105 The results showed that the effect of daily WFC on daily status anxiety was weaker when work-family centrality was high (B = 0.145, SE = 0.004, p < 0.01, 95% CI = [0.072, 0.217]), and stronger when work-family centrality was low (B = 0.312, SE = 0.047, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.234, 0.389]). In addition, the difference in the effects between the two groups was significant (B = –0.167, SE = 0.064, p < 0.01, 95% CI = [–0.273, –0.061]). The interaction plot was shown in Figure 4. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

|

Figure 4 Interaction effect of work-to-family conflict and work-family centrality on status anxiety in Study 2. |

To test hypothesis 4, with conspicuous consumption as the outcome variable, the operation of the whole model produces a significant moderating effect of work-family centrality (B = –0.102, SE = 0.046, p < 0.01, 95% CI = [–0.178, –0.027]). Specifically, the mediating effect of status anxiety in the relationship between daily WFC and conspicuous consumption was weaker for individuals with high work-family centrality (B = 0.097, SE = 0.036, p < 0.01, 95% CI = [0.038, 0.157]), and stronger for individuals with low work-family centrality (B = 0.200, SE = 0.057, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.107, 0.293]). The results were displayed in Table 5. Taken together, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

|

Table 5 Regression Results for the Moderated Mediation Effect |

Discussion

The study drew on identity theory24,25 to conceptualize the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption. The results from a cross-sectional survey and a daily diary study supported the hypothesized model. They showed that WFC predicted conspicuous consumption intentions by increasing status anxiety. In particular, WFC was a more substantial daily predictor of conspicuous consumption for individuals with lower work-family centrality.

Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the literature in the following aspects. First, our paper provides a new theoretical perspective for future research on the work-family interface. Previous studies have mainly studied the impact of WFC on people from the theory of Conservation of Resources.52,55,117,118 However, for the two crucial identities of work and family, the success of people’s self-verification of these two identities will certainly affect people’s psychology and behavior. Our study suggested that WFC makes it difficult for people to complete self-verification, resulting in the difference between the actual self and the ought self, leading to status anxiety. Thus, our study can serve not only as a test of identity theory but also as a new attempt to use a new theory for research on the work-family interface.

Second, this study adds to the previous literature on the extra-organizational behavioral consequences of WFC. This study takes into account the diversity of employees’ roles and argues that the impact of WFC on employees should also be diverse. In particular, the impact of work-family conflict on employees’ behavior is not limited to the internal organization, but may also have an impact on extra-organizational behavior. While previous studies have primarily focused on the negative psychological and organizational behaviors of WFC, our study broadens the impact of WFC to a ubiquitous behavior—consumer behavior. Previous findings on the effects of WFC include mental health,1,3,12–14 physical health,16,17 and the emerging results on behavioral health.18–20 The present study joins these studies to demonstrate that WFC impacts employees’ behavioral health by elucidating the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption. In this sense, our study contributes to constructing a complete picture of WFC outcome variables.

Furthermore, the present study also enriches the negative psychological consequences of WFC. Our study showed that in the context of WFC, employees would experience status anxiety which is a kind of agitation-related emotion.28 Previous studies have shown that WFC can lead to negative psychological states, such as dissatisfaction, exhaustion, stress, depression, and other dejection-related emotions.1,3,12–14 Through factor analysis, cluster analysis, and circular scaling, psychologists found that dejection-related emotions and agitation-related emotions are two different negative emotional states, which are also distinguished in many clinical literatures.28 In this sense, our study enriches the results of previous studies on the impact of WFC on people’s mental health.

Besides, the current study contributes to a broader understanding of how employee status anxiety develops. As status anxiety can cause severe problems for individuals and society (eg, weight problems, drug use, and social mobility),119 the risk factors for increasing status anxiety have received much attention in previous studies (eg, sociocultural and income inequality85,106,120 and social comparison).121 The findings of this paper suggested that daily WFC as a chronic stressor should also be considered regarding its positive relationship with status anxiety.

Finally, our study expands the prior research on work-family centrality in the work-family interface which focused primarily on the centrality moderating role of WFC-related or family related issues,40,109,122 by examining the moderating role of work-family centrality on the effect of WFC on employees’ status anxiety. Earlier researchers have called for more exploration of the moderating effect of work-family centrality on the relationship between work-family conflict and its consequences.66 In responding to the call, we found that the work-family centrality, as an individual trait, could buffer the effect of WFC on status anxiety even at the daily level.

Practical Implications

Our research has several important practical implications. Firstly, this study identifies WFC as a hidden cause of conspicuous consumption. Admittedly, conspicuous consumption is a kind of irrational consumer which has been linked with many negative outcomes.123–125 Employees and organizations should be aware of the adverse effects of WFC on this irrational consumption behavior. Employees are suggested to seek solutions to alleviate WFC to mitigate their conspicuous consumption tendency. Unfortunately, WFC will not be eliminated quickly and directly. Even so, employees should understand that conspicuous consumption is only an irrational means temporarily to relieve the anxiety caused by work-family conflicts. It should be curtailed. Meantime, based on our findings, companies can provide welfare to meet the consumption needs of employees with great WFC. For example, managers can present goods with conspicuous characteristics (eg, suitcases with distinctive logos) as employee benefits to satisfy their conspicuous intentions.

Secondly, unlike previous studies’ findings that WFC can cause dejection-related emotions,1,3,12–14 our findings show that WFC may cause status anxiety. These two types of negative emotions are clinically different and should be taken seriously by organizations and employees. Besides, the results of this study remind researchers and organizations that status anxiety arises not only in the context of inequality and social comparison but also in daily work interfering with family. Organizations could offer training sessions about coping with WFC and arrange family-friendly practices (eg, invite family members to visit employees’ offices and learn about what they do to gain more family support) to reduce employees’ WFC and status anxiety.20,126

Finally, our findings show that work-family centrality moderates the relationship between WFC and status anxiety. The practical implications of such a finding might be two-fold. First, managers could strengthen employees’ work identity to alleviate the adverse effects of WFC, for example, by emphasizing the importance and meaning of employees’ work and giving more supervisor support to help employees achieve self-actualization at work.5,41 Second, although employees’ work-family centrality is usually stable and hard to change,98 organizations could supply differentiated management by identifying employees’ work-family centrality. For example, when selecting candidates for jobs with high work demands, organizations could consider their level of work-family centrality to help them achieve work-family balance.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although a cross-sectional survey and a daily diary study were used to ensure the rigor of the conclusion, some limitations still need to be considered. Firstly, we only looked into the boundary condition of work-family centrality in the association between WFC and status anxiety. Existing research notes that some positive psychology, such as trait mindfulness, can be used to mitigate the adverse effects of WFC.127 Future studies may consider positive psychology (such as mindfulness) as a boundary condition for the relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption. Such research may provide actionable recommendations on how companies and employees can manage and address the negative effects of WFC, such as a mindfulness‐based training intervention.128

Second, we only looked at one mediating factor in the connection between WFC and conspicuous consumption-status anxiety. According to a 20-year longitudinal study, WFC affects people’s levels of self-esteem.129 As low self-esteem levels foster conspicuous consumption,30 future studies could investigate the mediation role of self-esteem in this relationship between WFC and conspicuous consumption to understand the association between them and help choose the most effective interventions.

Third, we investigated only one consumption behavior (ie, conspicuous consumption) as the dependent variable because people who worry about status are likelier to adopt conspicuous consumption.130 Since people with status anxiety also tend to show superiority through self-enhancement,131 future research could examine the effect of WFC on employees’ product preferences for self-enhancement characteristics. This line of research could expand our understanding of the impact of WFC on consumption behavior.

Conclusion

The main findings of this study are the confirmation through cross-sectional data and micro-longitudinal diary studies that WFC is the hidden cause of conspicuous consumption through increased status anxiety, a relationship moderated by work-family centrality. WFC is one of the most critical issues in employee health. It is not only associated with mental health1,3,12–14 and physical health16,17 but may also be a potential trigger for irrational conspicuous consumption. Employees should understand the effects of WFC on their anxiety and conspicuous consumption and look through their consumption intentions to avoid irrational consumption behavior. Organizations can use differentiation management (eg, assigning work based on an employee’s work-family centrality) to minimize employees’ status anxiety caused by their WFC. Besides, gifts to employees with bragging characteristics can reduce subsequent irrational consumption behaviors triggered by WFC. These findings contribute to developing prevention and intervention programs on health issues in WFC and provide a new direction for future research.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Central South University Institutional Review Board. The procedures used in this study complied with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editor and reviewers, and Pro. Julan Xie, Dr. Jian Li for their time and effort in helping to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 72072185).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Wang Y, Liu L, Wang J, Wang L. Work-family conflict and burnout among Chinese doctors: the mediating role of psychological capital. J Occup Health. 2012;54(3):232–240. doi:10.1539/joh.11-0243-oa

2. Haar JM. The downside of coping: work-family conflict, employee burnout and the moderating effects of coping strategies. J Manag Organ. 2006;12(2):146–159. doi:10.5172/jmo.2006.12.2.146

3. Hege A, Lemke MK, Apostolopoulos Y, Whitaker B, Sönmez S. Work-life conflict among US long-haul truck drivers: influences of work organization, perceived job stress, sleep, and organizational support. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(6):984. doi:10.3390/ijerph16060984

4. Vieira JM, Matias M, Lopez FG, Matos PM. Work-family conflict and enrichment: an exploration of dyadic typologies of work-family balance. J Vocat Behav. 2018;109:152–165. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.10.007

5. Seiger CP, Wiese BS. Social support from work and family domains as an antecedent or moderator of work-family conflicts? J Vocat Behav. 2009;75(1):26–37. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2009.03.001

6. Zhang M, Foley S, Yang B. Work-family conflict among Chinese married couples: testing spillover and crossover effects. Int J Human Resource Manag. 2013;24(17):3213–3231. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.763849

7. Siu O, Spector PE, Cooper CL, Lu C. Work stress, self-efficacy, Chinese work values, and work well-being in Hong Kong and Beijing. Int J Stress Manag. 2005;12(3):274–288. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.12.3.274

8. Whiston SC, Cinamon RG. The work-family interface: integrating research and career counseling practice. Career Dev Q. 2015;63(1):44–56. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2015.00094.x

9. Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Res. 1985;10(1):76–88. doi:10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

10. Allen TD, Regina J, Wiernik BM, Waiwood AM. Toward a better understanding of the causal effects of role demands on work–family conflict: a genetic modeling approach. J Appl Psychol. 2022. doi:10.1037/apl0001032

11. Allen TD, Herst DEL, Bruck CS, Sutton M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. J Occup Health Psych. 2000;5(2):278–308. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.278

12. Kan D, Yu X. Occupational stress, work-family conflict and depressive symptoms among Chinese bank employees: the role of psychological capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(1):134. doi:10.3390/ijerph13010134

13. Kremer I. The relationship between school-work-family-conflict, subjective stress, and burnout. J Manage Psychol. 2016;31(4):805–819. doi:10.1108/jmp-01-2015-0014

14. Blanco-Donoso LM, Moreno-Jiménez J, Hernández-Hurtado M, Cifri-Gavela JL, Jacobs S, Garrosa E. Daily work-family conflict and burnout to explain the leaving intentions and vitality levels of healthcare workers: interactive effects using an experience-sampling method. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1932. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041932

15. Zeb S, Akbar A, Gul A, Haider SA, Poulova P, Yasmin F. Work-family conflict, emotional intelligence, and general self-efficacy among medical practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:1867–1876. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S333070

16. Haynes SG, Eaker ED, Feinleib M. The effect of employment, family, and job stress on coronary heart disease patterns in women. In: Gold EB, editor. The Changing Risk of Disease in Women: An Epidemiological Approach. Lexington, MA: Heath; 1984:37–48.

17. Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Relation of work-family conflict to health outcomes: a four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1997;70(4):325–335. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00652.x

18. Liu Y, Wang M, Chang C, Shi J, Zhou L, Shao R. Work-family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and displaced aggression toward others: the moderating roles of workplace interpersonal conflict and perceived managerial family support. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100(3):793–808. doi:10.1037/a0038387

19. Gu X, Xu G, Qian C, Chang S, Deng D. Excess and defect: how job-family responsibilities congruence effect the employee procrastination behavior. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:1465–1480. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S365079

20. Chen Y, Zhang F, Wang Y, Zheng J. Work-family conflict, emotional responses, workplace deviance, and well-being among construction professionals: a sequential mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6883. doi:10.3390/ijerph17186883

21. Lozza E, Castiglioni C, Bonanomi A. The effects of changes in job insecurity on daily consumption and major life decisions. Econ Ind Democr. 2020;41(3):610–629. doi:10.1177/0143831x17731611

22. Sayre GM, Grandey AA, Chi NW. From cheery to “cheers”? Regulating emotions at work and alcohol consumption after work. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(6):597–618. doi:10.1037/apl0000846

23. Morgado C, Lima J. Body mass index, shift work and food consumption: what relationship? Eur J Public Health. 2021;31(Supplement_2):

24. Stets JE, Burke PJ. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc Psychol Quart. 2000;63(3):224–237. doi:10.2307/2695870

25. Stryker S, Burke PJ. The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Soc Psychol Quart. 2000;63(4):284–297. doi:10.2307/2695840

26. Botton AD. Status Anxiety. London: Hamish Hamilton; 2004.

27. Mandel N, Rucker DD, Levav J, Galinsky AD. The compensatory consumer behavior model: how self-discrepancies drive consumer behavior. J Consum Psychol. 2017;27(1):133–146. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2016.05.003

28. Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychol Rev. 1987;94(3):319–340. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.94.3.319

29. Jaikumar S, Singh R, Sarin A. “I show off, so I am well off”: subjective economic well-being and conspicuous consumption in an emerging economy. J Bus Res. 2018;86:386–393. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.05.027

30. Bharti M, Suneja V, Bharti M. Mindfulness as an antidote to conspicuous consumption: the mediating roles of self-esteem, self-concept clarity and normative influence. Pers Indiv Differ. 2022;184:111215. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111215

31. Haar JM, Roche M, ten Brummelhuis L. A daily diary study of work-life balance in managers: utilizing a daily process model. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2018;29(18):2659–2681. doi:10.1080/09585192.2017.1314311

32. Allen TD, French KA, Braun MT, Fletcher K. The passage of time in work-family research: toward a more dynamic perspective. J Vocat Behav. 2019;110:245–257. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.013

33. Wu Y, Eisenegger C, Sivanathan N, Crockett MJ, Clark L. The role of social status and testosterone in human conspicuous consumption. Sci Rep-UK. 2017;7(1):1–8. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12260-3

34. Kievit RA, Frankenhuis WE, Waldorp LJ, Borsboom D. Simpson’s paradox in psychological science: a practical guide. Front Psychol. 2013;4:513. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00513

35. Hamaker EL. Why researchers should think “within-person”: a paradigmatic rationale. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Daily Life. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2012:43–61.

36. Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN. Social support as an individual difference variable: its stability, origins, and relational aspects. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50(4):845. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.4.845

37. Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: capturing life as it is lived. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54(1):579–616. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030

38. Derks D, Bakker AB, Gorgievski M. Private smartphone use during work time: a diary study on the unexplored costs of integrating the work and family domains. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;114:106530. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106530

39. Xue Q, Yang J, Wang H, Zhang D. How and when leisure crafting enhances college students’ well-being: a (quantitative) weekly diary study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:273. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S344717

40. Carr JC, Boyar SL, Gregory BT. The moderating effect of work-family centrality on work-family conflict, organizational attitudes, and turnover behavior. J Manage. 2008;34(2):244–262. doi:10.1177/0149206307309262

41. Jiang L, Johnson MJ. Meaningful work and affective commitment: a moderated mediation model of positive work reflection and work centrality. J Bus Psychol. 2017;33(4):545–558. doi:10.1007/s10869-017-9509-6

42. Gupta S, Verma HV. Mindfulness, mindful consumption, and life satisfaction. J Appl Res High Educ. 2019;12(3):456–474. doi:10.1108/JARHE-11-2018-0235

43. Choung Y, Pak TY, Chatterjee S. Consumption and life satisfaction: the Korean evidence. Int J Consum Stud. 2021;45(5):1007–1019. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12620

44. Stryker S. Identity theory: developments and extensions. In: Yardley K, Honess T, editors. Self and Identity: Psychosocial Perspectives. Vol. 37. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987:89–103.

45. Thoits PA. On merging identity theory and stress research. Soc Psychol Quart. 1991;54(2):101–112. doi:10.2307/2786929

46. Stets JE, Biga CF. Bringing identity theory into environmental sociology. Sociol Theor. 2003;21(4):398–423. doi:10.1046/j.1467-9558.2003.00196.x

47. Davis JL, Love TP, Fares P. Collective social identity: synthesizing identity theory and social identity theory using digital data. Soc Psychol Quart. 2019;82(3):254–273. doi:10.1177/0190272519851025

48. Dewey AM. Conceptualizing environmental movement identity standards: the role of personal identity theory. Soc Nat Resour. 2021;34(5):585–602. doi:10.1080/08941920.2020.1854406

49. Stets JE. Status and identity in marital interaction. Soc Psychol Quart. 1997;60:185–217. doi:10.2307/2787082

50. Guitian G. Conciliating work and family: a catholic social teaching perspective. J Bus Ethics. 2009;88(3):513–524. doi:10.2307/2695870

51. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11(4):227–268. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1104_01

52. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–524. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513

53. Macey WH, Schneider B. The meaning of employee engagement. Ind Organ Psychol-US. 2008;1(1):3–30. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2007.0002.x

54. Marungruang P, Wongwanich S, Tangdhanakanond K. Development and preliminary psychometric properties of a parenting quality scale. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;116:1696–1703. doi:10.1080/08964289.2021.2002799

55. Hoobler JM, Hu J, Wilson M. Do workers who experience conflict between the work and family domains hit a “glass ceiling?”: a meta-analytic examination. J Vocat Behav. 2010;77(3):481–494. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.07.001

56. Song Z, Foo M-D, Uy MA, Sun S. Unraveling the daily stress crossover between unemployed individuals and their employed spouses. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96(1):151–168. doi:10.1037/a0021035

57. Md‐Sidin S, Sambasivan M, Ismail I. Relationship between work-family conflict and quality of life. J Manage Psychol. 2010;25(1):58–81. doi:10.1108/02683941011013876

58. Heine SJ, Proulx T, Vohs KD. The meaning maintenance model: on the coherence of social motivations. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2006;10(2):88–110. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_1

59. Braun OL, Wicklund RA. Psychological antecedents of conspicuous consumption. J Econ Psychol. 1989;10(2):161–187. doi:10.1016/0167-4870(89)90018-4

60. Gao L, Wheeler SC, Shiv B. The “shaken self”: product choices as a means of restoring self-view confidence. J Consum Res. 2009;36(1):29–38. doi:10.1086/596028

61. Willer R, Rogalin CL, Conlon B, Wojnowicz MT. Overdoing gender: a test of the masculine overcompensation thesis. Am J Sociol. 2013;118(4):980–1022. doi:10.1086/668417

62. Rucker DD, Galinsky AD. Desire to acquire: powerlessness and compensatory consumption. J Consum Res. 2008;35(2):257–267. doi:10.1086/588569

63. Charles KK, Hurst E, Roussanov N. Conspicuous consumption and race. Q J Econ. 2009;124(2):425–467. doi:10.1162/qjec.2009.124.2.425

64. Rucker DD, Galinsky AD. Conspicuous consumption versus utilitarian ideals: how different levels of power shape consumer behavior. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2009;45(3):549–555. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.01.005

65. Lee J, Shrum LJ. Conspicuous consumption versus charitable behavior in response to social exclusion: a differential needs explanation. J Consum Res. 2012;39(3):530–544. doi:10.1086/664039

66. Sivanathan N, Pettit NC. Protecting the self through consumption: status goods as affirmational commodities. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46(3):564–570. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.01.006

67. O’Cass A, McEwen H. Exploring consumer status and conspicuous consumption. J Consum Behav. 2004;4(1):25–39. doi:10.1002/cb.155

68. Jensen M. Should we stay or should we go? accountability, status anxiety, and client defections. Admin Sci Quart. 2006;51(1):97–128. doi:10.2189/asqu.51.1.97

69. Lee J, Ko E, Megehee CM. Social benefits of brand logos in presentation of self in cross and same gender influence contexts. J Bus Res. 2015;68(6):1341–1349. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.12.004

70. Shin SA, Jang JO, Kim JK, Cho EH. Relations of conspicuous consumption tendency, self-expression satisfaction, and SNS Use satisfaction of Gen Z through SNS activities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):11979. doi:10.3390/ijerph182211979

71. Griskevicius V, Kenrick DT. Fundamental motives: how evolutionary needs influence consumer behavior. J Consum Psychol. 2013;23(3):372–386. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2013.03.003

72. Zheng X, Baskin E, Peng S. Feeling inferior, showing off: the effect of nonmaterial social comparisons on conspicuous consumption. J Bus Res. 2018;90:196–205. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.041

73. Cushman P. Why the self is empty. Toward a historically situated psychology. Am Psychol. 1990;45(5):599–611.

74. Bagger J, Li A. Being important matters: the impact of work and family centralities on the family-to-work conflict-satisfaction relationship. Hum Relat. 2012;65(4):473–500. doi:10.1177/0018726711430557

75. Rothbard NP, Edwards JR. Investment in work and family roles: a test of identity and utilitarian motives. Pers Psychol. 2003;56(3):699–729. doi:10.1111/J.1744-6570.2003.TB00755.X

76. Carlson DS, Kacmar KM. Work-family conflict in the organization: do life role values make a difference? J Manage. 2000;26(5):1031–1054. doi:10.1016/s0149-2063(00)00067-2

77. Carlson DS, Kacmar KM, Williams LJ. Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. J Vocat Behav. 2000;56(2):249–276. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1999.1713

78. Kinnunen U, Feldt T, Mauno S, Rantanen J. Interface between work and family: a longitudinal individual and crossover perspective. J Occup Organ Psych. 2010;83(1):119–137. doi:10.1348/096317908x399420

79. Ma H, Xie J, Tang H, Shen C, Zhang X. Relationship between working through information and communication technologies after hours and well-being among Chinese dual-earner couples: a spillover-crossover perspective. Acta Psychol Sin. 2016;48(1):48–58. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016.00048

80. Xie J, Zhou ZE, Gong Y. Relationship between proactive personality and marital satisfaction: a spillover-crossover perspective. Pers Indiv Differ. 2018;128:75–80. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.02.011

81. Wang CX, Zhu H. Status anxiety, materialism and conspicuous consumption—Status, antecedents and consequences of Chinese materialism. Soc Sci Beijing. 2016;5:31–40. doi:10.13262/j.bjsshkxy.bjshkx.160504

82. Marcoux JS, Filiatrault P, Chéron E. The attitudes underlying preferences of young urban educated Polish consumers towards products made in western countries. J Int Consum Mark. 1997;9(4):5–29. doi:10.1300/j046v09n04_02

83. Yuan S, Gao Y, Zheng Y. Face consciousness, status consumption tendency and conspicuous consumption behavior—theoretical relationship model and empirical research. Collect Essays Financ Econ. 2009;5:81–86. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-4892.2009.05.013

84. Segal B, Podoshen JS. An examination of materialism, conspicuous consumption and gender differences. J Int Consum Mark. 2013;37(2):189–198.

85. Paskov M, Gërxhani K, van de Werfhorst HG. Income inequality and status anxiety. Growing Inequality Impacts. 2013;90:1–46.

86. Karatepe OM. An investigation of the joint effects of organisational tenure and supervisor support on work-family conflict and turnover intentions. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2009;16(1):73–81. doi:10.1375/jhtm.16.1.73

87. Bennett MM, Beehr TA, Ivanitskaya LV. Work-family conflict: differences across generations and life cycles. J Manage Psychol. 2017;32(4):314–332. doi:10.1108/jmp-06-2016-0192

88. Layte R. The association between income inequality and mental health: testing status anxiety, social capital, and neo-materialist explanations. Eur Sociol Rev. 2012;28(4):498–511. doi:10.1093/esr/jcr012

89. Winkelmann R. Conspicuous consumption and satisfaction. J Econ Psychol. 2012;33(1):183–191. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2011.08.013

90. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2013.

91. Matijaš M, Merkaš M, Brdovčak B. Job resources and satisfaction across gender: the role of work-family conflict. J Manage Psychol. 2018;33(4/5):372–385. doi:10.1108/JMP-09-2017-0306

92. Xie J, Ma H, Zhou ZE, Tang H. Work-related use of information and communication technologies after hours (W_ICTs) and emotional exhaustion: a mediated moderation model. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;79:94–104. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.023

93. Gong Y, Tang X, Xie J, Zhang L. Exploring the nexus between work-to-family conflict, material rewards parenting and adolescent materialism: evidence from Chinese dual-career families. J Bus Ethics. 2020;1–15. doi:10.1007/s10551-020-04681-4

94. Ohly S, Sonnentag S, Niessen C, Zapf D. Diary studies in organizational research: an introduction and some practical recommendations. J Pers Psychol. 2010;9(2):79. doi:10.1027/1866-5888/a000009

95. Garrosa E, Blanco-Donoso LM, Carmona-Cobo I, Moreno-Jiménez B. How do curiosity, meaning in life, and search for meaning predict college students’ daily emotional exhaustion and engagement? J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(1):17–40. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9715-3

96. Basinska BA, Gruszczynska E. Burnout as a state: random-intercept cross-lagged relationship between exhaustion and disengagement in a 10-day study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:267. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S262432

97. Stavrova O, Ren D, Pronk T. Low self-control: a hidden cause of loneliness? Pers Soc Psychol B. 2022;48(3):347–362. doi:10.1177/01461672211007228

98. Hirschfeld RR, Feild HS. Work centrality and work alienation: distinct aspects of a general commitment to work. J Organ Behav. 2000;21(7):789–800. doi:10.1002/1099-1379(200011)21:7<789::aid-job59>3.0.co;2-w

99. Scherbaum CA, Ferreter JM. Estimating statistical power and required sample sizes for organizational research using multilevel modeling. Organ Res Methods. 2009;12(2):347–367. doi:10.1177/1094428107308906

100. Foo M-D, Uy MA, Baron RA. How do feelings influence effort? An empirical study of entrepreneurs’ affect and venture effort. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(4):1086. doi:10.1037/a0015599

101. Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. Work engagement and financial returns: a diary study on the role of job and personal resources. J Occup Organ Psych. 2009;82(1):183–200. doi:10.1348/096317908x285633

102. Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, Mcmurrian R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):400–410. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400

103. Hill EJ. Work-family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and mothers, work-family stressors and support. J Fam Issues. 2005;26(6):793–819. doi:10.1177/0192513x05277542

104. Clinton ME, Conway N, Sturges J, Hewett R. Self-control during daily work activities and work-to-nonwork conflict. J Vocat Behav. 2020;118:103410. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103410

105. Keshabyan A, Day MV. Concerned whether you’ll make It in life? Status anxiety uniquely explains job satisfaction. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1523. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01523

106. Melita D, Willis GB, Rodríguez-Bailón R. Economic inequality increases status anxiety through perceived contextual competitiveness. Front Psychol. 2021;12:637365. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.637365

107. Kruger DJ. Phenotypic mimicry distinguishes cues of mating competition from paternal investment in men’s conspicuous consumption. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2021;48(3):396–411. doi:10.1177/01461672211007229

108. Govind R, Garg N, Mittal V. Weather, affect, and preference for hedonic products: the moderating role of gender. J Market Res. 2020;57(4):717–738. doi:10.1177/0022243720925764

109. Xie J, Shi Y, Ma H. Relationship between similarity in work-family centrality and marital satisfaction among dual-earner couples. Pers Indiv Differ. 2017;113:103–108. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.021

110. Shi Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Ma H. Work-related use of information and communication technologies after hours and focus on opportunities: the moderating role of work-family centrality. Curr Psychol. 2018;1–8. doi:10.1007/s12144-018-9979-3

111. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998.

112. Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2006;31(4):437–448. doi:10.3102/10769986031004437

113. Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, Zhang Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychol Methods. 2010;15(3):209–233. doi:10.1037/a0020141

114. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB. Using Multivariate Statistics. Vol. 5. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2007.

115. Sonnentag S, Eck K, Fritz C, Kühnel J. Morning reattachment to work and work engagement during the day: a look at day-level mediators. J Manage. 2020;46(8):1408–1435. doi:10.1177/0149206319829823

116. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences.

117. Glaser W, Hecht TD. Work-family conflicts, threat-appraisal, self-efficacy and emotional exhaustion. J Manage Psychol. 2013;28(2):164–182. doi:10.1108/02683941311300685

118. Lu C, Lu J, Du D, Brough P. Crossover effects of work-family conflict among Chinese couples. J Manage Psychol. 2016;31(1):235–250. doi:10.1108/JMP-09-2012-0283

119. Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone. London: Penguin; 2010.

120. Delhey J, Schneickert C, Steckermeier LC. Sociocultural inequalities and status anxiety: redirecting the spirit level theory. Int J Comp Sociol. 2017;58(3):215–240. doi:10.1177/0020715217713799

121. Ebarajakirthy C, Das M. How self-construal drives intention for status consumption: a moderated mediated mechanism. J Retail Consum Serv. 2020;55. doi:10.1177/0020715217713799

122. Orgambídez-Ramos A, Mendoza-Sierra MI, Giger J. The effects of work values and work centrality on job satisfaction. A study with older Spanish workers. J Spat Organ Dyn. 2013;1(3):179–186.

123. Linssen R, van Kempen L, Kraaykamp G. Subjective well-being in rural India: the curse of conspicuous consumption. Soc Indic Res. 2011;101(1):57–72. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9635-2

124. Mi L, Yu X, Yang J, Lu J. Influence of conspicuous consumption motivation on high-carbon consumption behavior of residents—an empirical case study of Jiangsu province, China. J Clean Prod. 2018;191:167–178. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.109

125. Jaikumar S, Sharma Y. Consuming beyond means: debt trap of conspicuous consumption in an emerging economy. J Market Theory Prac. 2021;29(2):233–249. doi:10.1080/10696679.2020.1816476

126. Da S, Fladmark SF, Wara I, Christensen M, Innstrand ST. To change or not to change: a study of workplace change during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):1982. doi:10.3390/ijerph19041982

127. Morganson VJ, Rotch MA, Christie AR. Being mindful of work-family issues: intervention to a modern stressor. Ind Organ Psychol. 2015;8(04):682–689. doi:10.1017/iop.2015.100

128. Kiburz KM, Allen TD, French KA. Work-family conflict and mindfulness: investigating the effectiveness of a brief training intervention. J Organ Behav. 2017;38(7):1016–1037. doi:10.1002/job.2181

129. Li A, Shaffer JA, Wang Z, Huang JL. Work-family conflict, perceived control, and health, family, and wealth: a 20-year study. J Vocat Behav. 2021;127:103562. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103562

130. Huang Z, Wang CL. Conspicuous consumption in emerging market: the case of Chinese migrant workers. J Bus Res. 2018;86:366–373. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.08.010

131. Loughnan S, Kuppens P, Allik J, et al. Economic inequality is linked to biased self-perception. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(10):1254–1258. doi:10.1177/0956797611417003

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.