Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

The Relationship Between Supervisor Bottom-Line Mentality and Subordinate Work Performance: Linear or Curvilinear Effects?

Authors Zhang Y, Zhao H, Chen S

Received 25 November 2021

Accepted for publication 9 March 2022

Published 21 March 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 725—735

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S351206

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Einar Thorsteinsson

Yun Zhang,1 Hong Zhao,1 Song Chen2

1School of Management, Wuzhou University, Wuzhou, 543002, Guangxi, People’s Republic of China; 2Infrastructure Department, Wuzhou University, Wuzhou, 543002, Guangxi, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Hong Zhao, School of Management, Wuzhou University, Fumin 3rd Road, Wuzhou, 543002, Guangxi, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 189 077 483 38, Email [email protected] Song Chen, Infrastructure Department, Wuzhou University, Fumin 3rd Road, Wuzhou, 543002, Guangxi, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 180 706 096 16, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Combine the transactional model of stress and coping with the challenge and hindrance stressor framework. This study examined whether there is a linear or curvilinear relationship between supervisor bottom-line mentality (BLM), which emphasizes the pursuit of bottom-line results above all else, and the work performance of subordinates.

Materials and Methods: A total of 284 two-wave dual-source survey data have been collected from an insurance company in China. Analysis was conducted in two steps. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test the validity of scales. Second, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to examine the hypotheses.

Results: Results show that there has an inverted U-shaped (curvilinear) relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance. As the level of supervisor BLM increases from low to moderate, subordinate work performance increases; as the level of supervisor BLM increases from moderate to high, subordinate work performance decreases. Moreover, this study finds that the inverted U-shaped relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinates’ work performance was stronger when subordinates have higher power distance orientation.

Conclusion: Unlike previous studies which found a linear relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance, this study provided the first empirical examination of our hypothetical inverted U-shaped relationship of supervisor BLM impact on subordinate work performance. In addition, this study found that the relationship was stronger when subordinates had a higher power distance orientation.

Keywords: curvilinear relationship, supervisor bottom-line mentality, work performance, power distance orientation, transactional model of stress and coping, challenge and hindrance stressor framework

Introduction

In the past ten years, more and more research has focused on the positive or negative effects of supervisor bottom-line mentality in the workplace.1,2 Bottom-line mentality (BLM) is defined as “a one-dimensional frame of thinking that revolves around securing bottom-line outcomes to the neglect of competing priorities”.3 Supervisors who adopt BLM may consider that the bottom-line results, such as the achievement of financial goals, are the most important. And they seek to motivate subordinates accordingly.4

In line with this logic, a recent study based on social exchange theory concluded that supervisors’ pursuit of bottom-line goals would make subordinates feel an obligation to achieve those bottom-line results and improve their work performance.5 However, another study argued that this single focus reduces social exchange with subordinates thereby actually reducing overall performance.6 Obviously, our understanding of this relationship is incomplete.

We suggest there is more to stress than social exchange. Follow the notion that supervisors’ power influences the behavior of subordinates.7 We suggest that supervisors with bottom-line framework will motivate subordinates to work hard more by punishing than rewarding.3 If subordinates fail to meet supervisors’ requirements, they may face reprimand such as a salary cut, demotion or even dismissal, which adds undue pressure. Thus, we argue that supervisor BLM may act as a stressor to subordinates. However, limited attention has been placed on investigating the relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance from the stress perspective.3

Based on the transactional model of stress and coping, our study argues that subordinates would consider supervisor BLM as a source of stress and take a series of countermeasures. Moreover, according to the challenge and hindrance stressor framework,9 subordinates’ assessment of the pressure caused by supervisors’ requirements for economic goals may change as supervisor BLM increases. Specifically, when supervisor BLM is from low to middle level, subordinates evaluate it as a challenge stressor, so they actively engage in work and improve their performance. When supervisor BLM is from middle to high level, subordinates evaluate that as a hindrance stressor, which in-turn reduces their work performance.10 Therefore, we propose that there is an inverted U- curve relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance.

Furthermore, whether the stressor is a challenge or hindrance will be influenced by individual factors.9 Faced with supervisor BLM, subordinates who are more authoritative (which power distance orientation reflects) are more likely to perceive the pressure exerted by their supervisors,11 and then more likely to cope with the pressure psychologically and behaviorally. We further propose that subordinates’ power distance orientation moderates the relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinates’ work performance. This study explored the nature of the relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance, and whether this relationship differs according to different levels of subordinates’ power distance orientation.

By doing so, we make three theoretical contributions to the current literature. First, our study combines the transactional model of stress and coping with the challenge and hindrance stressor framework,9,12 and discusses in-depth the inverted U-shaped relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance, which theoretically explains the contradictions in the previous literature from a new perspective. Second, our study expects that when subordinates faced with supervisor BLM, they will have different pressure assessments due to different levels of supervisor BLM, and that will have different impacts on their work performance. Our study deeply explains this stress assessment and coping process, which can help researchers better understand the influence mechanism of supervisor BLM on subordinates’ workplace performance. Third, our study investigated whether the strength of the relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance differs among subordinates with different levels of power distance orientation, which contributes to the current literature. Specifically, we suggest that this inverted U-shape relationship will be stronger when subordinates have higher power distance orientation. Thus, our study provides a considerable boundary condition of the non-linear relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinates’ work performance.

Literature Review

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping

Based on the definition of “stress”,13 it is believed that stress will be activated when external demands exceed one’s own capabilities, prompting a reaction to those stressors by the individual, and causing them to deviate psychologically or physiologically from his/her normal functional states.13,14 Transactional model of stress and coping theory believes that when a stressor occurs, the individual will adopt primary appraisal, that is, anticipate the possible results of the stressor and associate it with personal growth and well-being.9 If this primary appraisal concludes that the stressor can be overcome and that personal growth will result, then the stressor will be considered as a “good” stressor. If the stressor is assessed as too high or threatens personal well-being, then it will be evaluated as a “bad” stressor. After the primary appraisal, the individual assesses what coping strategies should be adopted to eliminate or reduce the negative effects of the stressor, that is, they enter a secondary appraisal. The different appraisal results will trigger different psychological and behavioral responses.15

The Challenge and Hindrance Stressor Framework

Extending Lazarus and Folkman’s stress theory, some scholars proposed a two-dimensional stressor framework to explain the “good” and “bad” stressors and their relationship with workplace outcomes.12 This two-factor solution of stress can well explain the relationship between stressor and work-related psychology and behaviors.10 The first factor is called the challenge stressor, which generally comes from a reasonable level of workload, appropriate time pressure, a reasonable work scope, and responsibilities. Individuals tend to associate these pressures with their personal development and achievements.16 The second factor is called the hindrance stressor, which is generally caused by ambiguity in roles, organizational politics, and concerns about job security. Individuals tend to associate these work pressures with hindering personal growth and task completion.17

The proposed dual stressor framework provides a reasonable interpretation for scholars to discuss the possible positive or negative effects of pressure on individuals’ work performance.18 For example, a study suggested that a challenge stressor is positively correlated with work performance, while a hindrance stressor is negatively correlated with work performance through a meta-analysis test.10 Another study used the transactional theory of stress as a basis for developing hypotheses regarding differential relationships between the two types of stressors and work performance.13 These empirical results show that the effects of different stressors on work performance are inconsistent, because different stressors will cause individuals to have different expectations for the future, and these expectations will serve as psychological motivations to promote or hinder individuals from working hard.

The Relationship Between Supervisor BLM and Subordinate Work Performance

BLM, which refers to a one-dimensional framework that focuses only on bottom-line results, has raised concerns by scholars since it was mentioned by Greenbaum et al.3 Ensuring bottom-line results can often bring economic benefits to the organization,19 but it can also lead to a series of problems.19 Individuals with BLM usually have two important characteristics, one is pursuing the sole goal of bottom-line results, and the other is a competitive mindset of winning.20,21

According to the transactional model of stress and coping theory,9 supervisors adopting BLM only focus on the achievement of bottom-line goals and set work indicators for their subordinates accordingly. Faced with these indicators, subordinates would enter into the primary appraisal. They would link the completion of these tasks to their future benefits, and they will also assess whether they have the resources and capabilities to cope.13 They would rate the stressors as a challenge if they felt that these job requirements would bring potential benefits to them and that they were able to cope. Conversely, when they felt that the resources and abilities they have are not up to the job, or even lead to negative future impacts, they rate the stressors as a hindering.22 After the primary appraisal, they proceeded to the secondary appraisal, which is to respond to these stressors.23

Given this logic, we propose an inverted U-shaped (curve) relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinates’ work performance. More specifically, we argue that subordinates who work at moderate level of supervisor BLM are more likely to actively participate in work than those who work at low and high levels of supervisor BLM for two main reasons. First, we believe that when the level of supervisor BLM goes from low to moderate, the work performance of the subordinates improves. Based on the stress theory, challenge stress can improve individual work performance compared to the state of no stress.13 Supervisors with BLM will view the bottom-line goal as the ultimate goal and urge their subordinates to work hard for it.24 Through primary appraisal, the subordinates connect supervisors’ bottom-line goals with their own future well-being, and consider whether their personal resources can handle those requirements or not. Employees more or less have certain resources to complete tasks,25 so they tend to evaluate this stressor as a challenge-related stressor. When they enter the secondary appraisal, they tend to work hard and achieve the tasks to cope with the stress from supervisor BLM. Moreover, the moderate-level of supervisor BLM implements appropriate rewards and discipline systems to promote subordinates for their hard work, which also helps to improve the performance of subordinates.26 Secondly, we argue that when the level of supervisor BLM goes from moderate to high, subordinates’ work performance decreases. This is because when the level of supervisor BLM increases, supervisors’ persistence to the bottom-line goal transcends everything. They only pay attention to the achievement of the goal, and therefore put too much pressure on the subordinates and neglect to provide corresponding resources.1 When subordinates are short of resources, they largely consider supervisor BLM as a hindrance stressor.27,28 That is because once they fail to complete the supervisors’ goals, they will be severely punished. In order to avoid this situation, subordinates will invest more time and energy to prepare for the possible punishment (for example, looking for another job), thereby reducing their engagement in work.29 Meta-analysis also showed that hindrance stressors are negatively correlated with work performance.10 Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: There is an inverted U-shaped (curvilinear) relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance.

The Moderating Role of Subordinate Power Distance Orientation

The connotation of transactional model of stress and coping theory is that individuals assess stressors and then cope with them.22 In the process of primary appraisal, personal factors (such as values) will influence how they interpret these stressors.30–33 Power distance orientation is a part of those values, which refers to “the extent to which one accepts that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally”.34 Power distance orientation affects subordinates’ understanding of supervisors’ authority, shaping beliefs about which behaviors and mentality are characteristics of effective leadership.30,35 Thus, it plays an important role in individuals’ responses to stressors from their supervisors.11

Based on the possible influence of the power distance orientation on stress brought by supervisor BLM, we argued that the inverted U-shaped relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance differs between subordinates with different strengths of the power distance orientation. We believe that compared to subordinates with lower power distance orientation, the curve relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinates’ work performance will be stronger when subordinates have higher power distance orientation than those have lower power distance orientation. This is because the recognition of power would cause subordinates to show greater sensitivity to the expectations of their supervisors, and amplify the pressure brought by supervisor BLM.36 Therefore, when faced with supervisor BLM, they usually attempt to meet supervisors’ goal requirements, and appraise the associated pressure as a challenge stressor. However, when the pressure level exceeds their capacity, supervisor BLM is more likely to be evaluated as a hindrance stressor. The pressure from authority may make them tired of coping. They reduce engagement and turn to unethical behaviors that can yield more short-term benefits. Recent work supports this statement. For example, Zhang, He, Huang and Xie’s (2020) study demonstrated that subordinates with higher power distance orientation are more inclined to engage in unethical behaviors when faced with supervisor BLM.36 Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H2. The inverted U-shaped (curvilinear) relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinates’ work performance is stronger for subordinates with higher power distance orientation than for those with lower power distance orientation.

Materials and Methods

Sample

Participants were all full-time sales employees working in a large insurance company in China. In order to reduce common method bias (CMB), we conducted a two-wave dyads-survey with a gap of one month.37 Data was collected from subordinates and their supervisors in two waves. We asked subordinates to report their direct supervisors’ BLM, their power distance orientation and their demographic information (including age, gender, tenure with their present supervisor and educational level) at Time 1. At Time 2 we asked their direct supervisors to assess the subordinates’ work performance. Each supervisor was only matched with one subordinate. We got 284 valid matching questionnaires from Time1 and Time2. The proportion of female employees in our sample was 34.15%. In this study, 7.75% were between 18 and 20 years old, 23.59% between 21 and 30, 51.76% between 31 and 40, 7.75% between 41 and 50, and 9.15% were older than 51. In the sample, 2.11% of participants had worked with their current supervisor for less than 1 year, 5.99% for between 2 and 3 years, 20.77% for between 3 and 5 years, 62.32% for between 5 and 10 years, and 8.80% had worked for more than 10 years. 16.90% of the participants had a high school degree, 44.72% had a college degree or bachelor’s degree, and 38.38% had a master’s or doctoral degree.

Procedures

Before starting the survey, we shared our research purpose and potential benefits with the company’s top management team and HR department, who granted their support and access. We then emailed each subordinate one questionnaire with their work ID as a unique identifier, but only one participant in each team received a questionnaire which also included the supervisor BLM questionnaire. This participant was selected at random. One month later, we asked team supervisors to rate the performance of all subordinates, so that supervisors could not guess which subordinate was paired with them. Supervisors and subordinates completed the surveys at separate times in separate locations. We then matched the questionnaires of supervisors and subordinates base on subordinates’ work ID.

Measures

We adopted the widely used questionnaires to measure the substantive variables. And we followed a double-blind back-translation procedure to translate all the questionnaires into Chinese.

Supervisor BLM (T1)

We used Greenbaum et al’s four-item scale to assess supervisor BLM.3 Subordinates reported their direct supervisors’ BLM and rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items include: “My supervisor solely concerned with meeting the bottom line” and “My supervisor treats the bottom-line as more important than anything else”. The scale’s reliability was 0.90.

Subordinate Power Distance Orientation (T1)

We adapted Earley and Erez’s eight-item scale to measure subordinates’ power distance orientation (α = 0.94).38 Subordinates reported their power distance orientation and rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items are “Subordinates who often question authority sometimes keep their supervisors from being effective” and “In work-related matters, supervisors have a right to expect obedience from their subordinates.”

Subordinate Work Performance (T2)

Chen, Tsui, and Farh’s (2002) four-item scale was used to measure subordinates’ work performance.39 Supervisors were asked to reported their subordinates’ work performance during the past four weeks and rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The measurement has been validated and widely used in different research in the Chinese context.40 Sample items include: “she/he always completes job assignments on time” and “her/his performance always meets the expectations of the supervisor” The reliability of this scale was 0.87.

Control Variables (T1)

Following prior studies’ suggestions,24 we controlled subordinates’ age (1=18~20 years old, 2=21~30 years old, 3=31~40 years old, 4=41~50 years old, 5=older than 51 years), gender (1=female, 2=male), tenure with the current supervisor (1=less than one year, 2=2~3 years, 3=3~5 years, 4=5~10 years, 5=more than 10 years) and educational level (1= high school degree, 2= college degree or bachelor’s degree, 3= master’s or doctoral degree).

Data Analysis

We conducted two steps to analysis data by using Mplus V.6.11 and SPSS 26.0. First of all, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the validity of scales, and the descriptive statistics displayed participants’ statistical characteristics. Second, hierarchical regression analysis was took to test both hypotheses.

Result

Measurement Model

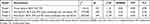

As showed in Table 1, a three factors model provided acceptable fit to the data (χ2 (101) =116.12, TLI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02). This model was also better than the other models. Compared to the one factor model, the three factors was significantly better. These results suggest that CMB is not a serious problem of this study. Furthermore, a one-way analysis of variance was conducted to assess the nested effect,42 which showed that the nesting within the organization did not have a significant impact on the relationship between the main variables.

|

Table 1 Comparison of Measurement Models |

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presented the means, standard deviations, and correlations of all variables.

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix |

Hypothesis Testing

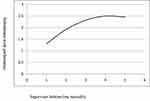

We conducted a hierarchical regression analysis to test Hypotheses 1 and 2, control variables were entered before other variables. The findings are shown in Table 3. As show in Model 2, supervisor BLM was found to be significantly related to subordinate work performance (B=0.30, SE=0.05, p<0.01), which consistent with previous research.43 However, the non-linear effects of supervisor BLM on subordinate work performance were examined through entering a quadratic term (BLM×BLM) into the regression (see Model 3), and the effects of the quadratic term is negative and significant (B = −0.11, SE=0.05, p<0.01) and explained an additional 1.4% in the variance. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Although the percentage of variance explained by the quadratic term is very small, it is consistent with previous organizational studies investigating non-linear effects.44 Figure 1 represents the inverted U-shaped relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance. As can be seen in Figure 1, as the level of supervisor BLM increases from low to moderate, subordinate work performance increases and as the level of supervisor BLM increases from moderate to high, subordinate work performance decreases.

|

Table 3 Regression Results |

|

Figure 1 Relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance. |

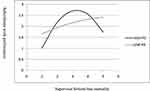

Hypothesis 2 stated that subordinates’ power distance orientation moderated the relationship between subordinate BLM and subordinates’ work performance. In order to test this hypothesis, the sample was split into two groups; subordinates with higher power distance orientation (higher than the mean of the sample) and subordinates with lower power distance orientation (lower than the mean of the sample). In Model 4, we ran a similar regression as Model 3 but only include subordinates with higher power distance orientation. In Model 5, we do the same, but for subordinates whose power distance orientation was lower than the mean of the sample. In line with Hypothesis 2, we found that the inverted U-shaped relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinates’ work performance was significant for subordinates have higher power distance orientation (B = −0.33, SE=0.07, p<0.01), but not significant for those have lower power distance orientation (B = −0.03, SE=0.06, p>0.05). Figure 2 shows this inverted U-shaped relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinates’ work performance for both groups. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

|

Figure 2 Relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance for subordinates high and low in power distance orientation. |

Discussion

This research provides a better understanding of the role that supervisor BLM plays in the subordinate work performance. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that there is an inverted u-curve relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance, and that the relationship is stronger for subordinates who have higher power distance orientation.

Theoretical Implications

Our study makes some theoretical implications. First, it may help clear up recent mixed assumptions about supervisors BLM on subordinate performance. In particular, although some studies have shown that supervisor BLM increases subordinate work performance through a sense of obligation to bottom-line goals,5 other studies have found the opposite.5 Given that our framework suggests that subordinates’ stress assessment of supervisor BLM and subordinates’ power distance orientation jointly influence individuals’ coping, this mixed outcome is to be expected, depending on whether subordinates assess supervisor BLM as a challenging stressor or a hindering stressor. The model proposed in this study provides a more complete explanation of the relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance by assuming that subordinate responses to supervisor BLM are based on an assessment of the nature of stress brought on by supervisor BLM. In addition, our study links two theories in explaining supervisor stress and subordinate coping, which extends current thinking and research. Although previous studies have suggested that supervisor BLM may be a stressor,8 they largely ignored the possible differentiation of this stressor in more depth, which in turn has different effects on subordinates.

Second, we present a novel model to investigate how subordinates react to supervisor BLM at the broadest level. Specifically, our study found that supervisors with moderate-level BLM may motivate subordinates to work harder than those with low or high-level BLM. Supervisors with moderate level BLM send a message to their subordinates that their bottom-line thinking is aware of the need to reach financial goals, but their leadership awareness allows them to provide more resources and assistance to their subordinates. Subordinates appraise supervisor BLM as a challenge stressor and cope with it through working harder. This is why in previous studies supervisor BLM was considered to be an important mentality that can provide economic benefits for the organization.45 However, in the case of a low-level supervisor BLM, the supervisor pays less attention to economic goals and cannot motivate employees to work hard. Previous studies have pointed out that low goals and pressures are not conducive to promoting individuals’ performance.23,46 In contrast, supervisors with high level of BLM are typically focused on economic goals at the expense of employees, which makes subordinates appraise supervisor BLM as a hindrance stressor and in-turn reduce subordinates’ work performance.2,4 Therefore, from the perspective of stress and coping, our study complements the literature of BLM by examining the double-edged sword effect of supervisor BLM on subordinates performance in a unified model, which provides useful empirical data to help analyze and understand the two sides of supervisor BLM.

Third, our study also suggests that subordinates’ power distance orientation influences the strength of the relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance. This confirms the transactional model of stress and coping which highlights the importance of personal values in strengthening the impact of stressors on individual outcomes.9,47 This study found that when subordinates have higher power distance orientation, the curvilinear effect of supervisor BLM on subordinate’s work performance will be stronger. These differences are particularly evident when supervisors have moderate-level BLM. Subordinates having higher power distance orientation have a stronger perception of the authority and expectations of supervisors. Since superiors with moderate BLM level focus on economic results and provide relevant information, subordinates who work under these supervisors are most likely to appraise achievement to the bottom-line results as a challenge stressor and cope with it by working harder. Our findings extend the application of power distance orientation in the field of stress coping.14

Managerial Implications

Our findings have some practical implications for organizations. First, given that our study revealed the existence of curvilinear effects of supervisor BLM on subordinate work performance, it is recommended that managers should use BLM with caution. Although supervisors adopt BLM to help set goals for subordinates, it can also inhibit subordinate work performance if it is not used in the right way. Our research results also show that in terms of improving subordinates’ work performance, a moderate BLM may be better than no exercise at all, which is consistent with previous research.45 Therefore, in order to improve the work performance of subordinates, taking appropriate bottom-line thinking while providing subordinates with the required resources can effectively improve their work performance.

Second, our findings indicate that subordinates improve their work performance because they assess the supervisor BLM as a challenging stressor. In order to enhance performance of their employees, managers should set reasonable economic goals and provide the necessary resources to help subordinates accomplish these goals.

Third, our study also found that recognition of authority affects subordinates’ perception of pressure from supervisors. Managers should consider the impact of personal cultural values on employees’ performance of work tasks, and cultivate employees’ values by establishing a clear organizational structure and other methods. Especially in Asian countries (such as China and Japan) where the power distance orientation is stronger, it is more necessary to guide positive cultural values through organizational culture construction.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Our study has several limitations and directions for future studies. First, although we collected data in two waves and from different sources, it provides weak evidence for causality.41 Future studies can use a longitudinal panel design to test the conclusions of this research. Second, the study focused exclusively on the influence of supervisor BLM on subordinate work performance. The findings need to be examined using other outcomes to further confirm the complicated influence of supervisor BLM on subordinates’ work behavior. Third, our research focused on the moderating role of power distance at the individual level. It is not clear whether cultural values have a similar moderating effect. In the future, cross-cultural research should be used for further testing. Furthermore, since the sample of this study is from China, the validity of the model may be affected by social and cultural factors. Future research should consider collecting samples from other countries to re-test our research.

Conclusion

The current research contributes to the BLM literature by offering a new perspective on investigate the inverted U-shaped relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinate work performance. Our results show that as the level of supervisor BLM increases from low to moderate, subordinate work performance increases; as the level of supervisor BLM increases from moderate to high, subordinate work performance decreases. Moreover, this study suggests that the inverted U-shaped relationship between supervisor BLM and subordinates’ work performance was stronger when subordinates have higher power distance orientation. The current research emphasizes that organizations and managers should understand the negative effects of supervisory BLM, provide more resources and assistance to enable employees to improve their work performance.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. All procedures performed were by the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standard. All the procedures were approved by the ethical committee of School of Management, Wuzhou University.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was funded by the Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of Guangxi (20FGL042).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Eissa G, Wyland R, Gupta R. Supervisor to coworker social undermining: the moderating roles of bottom-line mentality and self-efficacy. J Manage Organ. 2018;26(5):1–18. doi:10.1017/jmo.2018.5

2. Farasat M, Azam A. Supervisor bottom-line mentality and subordinates’ unethical pro-organizational behavior. Pers Rev. 2020. doi:10.1108/PR-03-2020-0129

3. Greenbaum RL, Mawritz MB, Eissa G. Bottom-line mentality as an antecedent of social undermining and the moderating roles of core self-evaluations and conscientiousness. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(2):343–359. doi:10.1037/a0025217

4. Mesdaghinia S, Rawat A, Nadavulakere S. Why moral followers quit: examining the role of leader bottom-line mentality and unethical pro-leader behavior. J Bus Ethics. 2019;159:491–505. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-3812-7

5. Babalola M, Mawritz M, Greenbaum R, Ren S, Garba O. Whatever It takes: how and when supervisor bottom-line mentality motivates employee contributions in the workplace. J Manage. 2020;47(5):014920632090252. doi:10.1177/0149206320902521

6. Quade MJ, Mclarty BD, Bonner JM. The influence of supervisor bottom-line mentality and employee bottom-line mentality on leader-member exchange and subsequent employee performance. Hum Relat. 2019;73(1):1–25. doi:10.1177/0018726719858394

7. Liden RC, Erdogan B, Wayne SJ, Sparrowe RT. Leader-member exchange, differentiation, and task interdependence: implications for individual and group performance. J Organ Behav. 2006;27:723–746. doi:10.1002/job.409

8. Zhang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Yang X. Coping with supervisor bottom-line mentality: the mediating role of job insecurity and the moderating role of supervisory power. Curr Psychol. 2021. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02336-9

9. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984.

10. LePine JA, Podsakoff NP, LePine MA. A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: an explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Acad Manage J. 2005;48(5):764–775. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2005.18803921

11. Kirkman BL, Chen G, Farh I, Chen ZX, Lowe KB. Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: a cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Acad Manage J. 2009;52(4):744–764. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2009.43669971

12. Cavanaugh MA, Boswell WR, Roehling MV, Boudreau JW. An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85(1):65–74. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.85.1.65

13. LePine MA, Zhang Y, Crawford ER, Rich BL. Turning their pain to gain: charismatic leader influence on follower stress appraisal and job performance. Acad Manage J. 2016;59(3):1036–1059. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.0778

14. Peltokorpi V, Ramaswami A. Abusive supervision and subordinates’ physical and mental health: the effects of job satisfaction and power distance orientation. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2021;32(4):893–919. doi:10.1080/09585192.2018.1511617

15. Sharma PN, Pearsall MJ. Leading under adversity: interactive effects of acute stressors and upper-level supportive leadership climate on lower-level supportive leadership climate. Leadersh Q. 2016;27(6):856–868. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.08.003

16. De Witte H, Van Hootegem A. Job insecurity: challenge or Hindrance stressor? Review of the evidence and empirical test on entrepreneurs. In: Flexible Working Practices and Approaches. Cham: Springer; 2021:213–229.

17. Li Z, He B, Sun X. Does work stressors lead to abusive supervision? A study of differentiated effects of challenge and hindrance stressors. Psychol Res Behav Ma. 2020;13:573–588. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S249071

18. Zhang Y, LePine J, Buckman B, Wei F. It’s not fair … Or is it? The role of justice and leadership in explaining work stressor–job performance relationships. Acad Manage J. 2014;57:652–674. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.1110

19. Barsky A. Understanding the ethical cost of organizational goal-setting: a review and theory development. J Bus Ethics. 2008;81(1):63–81. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9481-6

20. Quade MJ, Wan M, Carlson DS, Kacmar KM, Greenbaum RL. Beyond the bottom line: don’t forget to consider the role of the family. J Manage. 2021. doi:10.1177/01492063211030546

21. Babalola M, Ren S, Ogbonnaya C, Riisla K, Soetan GT, Gok K. Thriving at work but insomniac at home: understanding the relationship between supervisor bottom-line mentality and employee functioning. Hum Relat. 2020;75(9). doi:10.1177/0018726720978687

22. Li Z, Cheng Y. Supervisor bottom-line mentality and knowledge hiding: a moderated mediation model. Sustainability. 2022;14(2):586. doi:10.3390/su14020586

23. Li F, Chen T, Lai X. How does a reward for creativity program benefit or frustrate employee creative performance? The perspective of transactional model of stress and coping. Group Organ Manage. 2017;43(1):1–38. doi:10.1177/1059601116688612

24. Leung K, Huang K, Su C. Curvilinear relationships between role stress and innovative performance: moderating effects of perceived support for innovation. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2011;84(4):741–758. doi:10.1348/096317910X520421

25. Babalola MT, Greenbaum RL, Amarnani RK, et al. A business frame perspective on why perceptions of top management’s bottom‐line mentality result in employees’ good and bad behaviors. Pers Psychol. 2019;73(1):19–41. doi:10.1111/peps.12355

26. Huang QH, Xing Y, Gamble J. Job demands-resources: a gender perspective on employee well-being and resilience in retail stores in China. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2019;30(8):1323–1341. doi:10.1080/09585192.2016.1226191

27. Haque A. Strategic human resource management and presenteeism: a conceptual framework to predict human resource outcomes. New Zealand J Hum Resour Manag. 2018;18(2):3–18.

28. Charoensukmongkol P. Supervisor-subordinate guanxi and emotional exhaustion: the moderating effect of supervisor job autonomy and workload levels in organizations. Asia Pacific Manag Rev. 2021;27(1):40–49. doi:10.1016/j.apmrv.2021.05.001

29. Charoensukmongkol P, Puyod JV. Mindfulness and emotional exhaustion in call center agents in the Philippines: moderating roles of work and personal characteristics. J Gen Psychol. 2020;149(1):72–96. doi:10.1080/00221309.2020.1800582

30. Haque A. Strategic HRM and organisational performance: does turnover intention matter? Int J Abras Technol. 2021;29(3):656–681. doi:10.1108/IJOA-09-2019-1877

31. Lin W, Wang L, Chen S. Abusive supervision and employee well-being: the moderating effect of power distance orientation. Appl Psychol. 2013;62(2):308–329. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00520.x

32. Fischer R, Smith P. Who cares about justice? The moderating effect of values on the link between organisational justice and work behaviour. Appl Psychol. 2006;55:541–562. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00243.x

33. Charoensukmongkol P, Pandey A. The influence of cultural intelligence on sales self-efficacy and cross-cultural sales presentations: does it matter for highly challenge-oriented salespeople? Manag Res Rev. 2020;43(12):1533–1556. doi:10.1108/MRR-02-2020-0060

34. Charoensukmongkol P, Suthatorn P. Linking improvisational behavior, adaptive selling behavior, and sales performance. Int J Product Perform Manag. 2020;70(7):1582–1603. doi:10.1108/IJPPM-05-2019-0235

35. Hofstede G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations.

36. Wang H, Han X, Li J. Supervisor narcissism and employee performance: a moderated mediation model of affective organizational commitment and power distance orientation. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2021;43(1):14–29. doi:10.1080/01973533.2020.1810042

37. Zhang Y, He B, Huang Q, Xie J. Effects of supervisor bottom-line mentality on subordinate unethical pro-organizational behavior. J Manage Psychol. 2020;35(5):419–434. doi:10.1108/JMP-11-2018-0492

38. Dawson KM, O’Brien K, Beehr TA. The role of hindrance stressors in the job demand-control-support model of occupational stress: a proposed theory revision. J Organ Behav. 2016;37(3):397–415. doi:10.1002/job.2049

39. Earley PC, Erez M. The Transplanted Executive: Why You Need to Understand How Workers in Other Countries See the World differently. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997.

40. Chen ZX, Tsui AS, Farh JL. Loyalty to supervisor vs. organizational commitment: relationships to employee performance in China. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2002;75:339–356. doi:10.1348/096317902320369749

41. Chen XP, Eberly MB, Chiang TJ, Farh JL, Cheng BS. Affective trust in Chinese leaders: linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. J Manage. 2011;40(3):796–819. doi:10.1177/0149206311410604

42. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

43. Tepper BJ, Moss SE, Duffy MK. Predictors of abusive supervision: supervisor perceptions of deep-level dissimilarity, relationship conflict, and subordinate performance. Acad Manag J. 2011;54(2):279–294. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2011.60263085

44. Zhang Y, Huang QH, Chen HJ, Xie J. The mixed blessing of supervisor bottom-line mentality: examining the moderating role of gender. Leadersh Organ Dev. 2021;42(8):1153–1167. doi:10.1108/LODJ-11-2020-0491

45. Miao Q, Newman A, Yu J, Xu L. The relationship between ethical leadership and unethical pro-organizational behavior: linear or curvilinear effects. J Bus Ethics. 2013;116:641–653. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1504-2

46. Wolfe DM. Is there integrity in the bottom line: managing obstacles to executive integrity. In: Srivastva S, editor. Executive Integrity: The Search for High Human Values in Organizational Life. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1988:140–171.

47. Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol. 2002;57(9):705–717. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.57.9.705

48. Griffin MA, Clarke S. Stress and well-being at work. In: Zedeck S, editor. APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011:359–397.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.