Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Relationship Between Perceptions of Leader Hypocrisy and Employees’ Knowledge Hiding Behaviors: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model

Authors Wang J, Tian S , Wang Y, Guo Y , Wei X, Zhou X , Zhang Y

Received 7 August 2022

Accepted for publication 29 December 2022

Published 15 January 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 133—147

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S381364

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Jiping Wang,1 Shuhui Tian,1 Yu Wang,2 Yujie Guo,1 Xiaoyang Wei,3 Xingchi Zhou,1 Yishi Zhang4,5

1School of Management, Wuhan Textile University, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China; 2School of International Business and Management, Sichuan International Studies University, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China; 3School of Foreign Studies, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China; 4School of Management, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China; 5School of Management, Jinan University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Yu Wang, School of International Business and Management, Sichuan International Studies University, 33 Zhuangzhi Road, Shapingba District, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China, 400031, Tel +86 13500320024, Fax +86 02365380035, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Knowledge-sharing is critical for the survival and development of today’s organization, but employees are not always willing to share their knowledge and sometimes even hide it intentionally or unintentionally. Taken from the leadership perspective, this paper aims to investigate the influence of leader hypocrisy on employees’ knowledge-hiding behaviors. Drawing on the self-determination theory (SDT), this paper explores the mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction, as well as the moderating effect of employees’ interdependent self-construal on the relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge-hiding behaviors. The moderated mediation effect is also tested.

Methods: The data were collected from companies located in mainland China. The data sample for analysis consists of 336 employees. Hierarchical regression analysis was adopted to test the hypotheses of our proposed model.

Results: Leader hypocrisy are positively related to knowledge-hiding behaviors (b = 0.490, p < 0.01). Basic psychological needs satisfaction plays a partial mediating role in such relationship (b =0.118, [0.056, 0.210]). The interdependent self-construal moderates the relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge-hiding behaviors (b = 0.134, p < 0.01), as well as the moderated mediation effect (BootSE = 0.018, [− 0.083, − 0.009]).

Conclusion: The results show that leader hypocrisy is positively related to knowledge-hiding behaviors, and basic psychological needs satisfaction partially mediates such relationship. The interdependent self-construal weakens the negative relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding.

Keywords: leader hypocrisy, basic psychological needs satisfaction, knowledge hiding, interdependent self-construal

Introduction

In today’s organizations, the extensive exchange and utilization of knowledge can effectively improve organizational innovation performance and increase an organization’s competitive advantages.1 However, existing shreds of evidence show that knowledge hiding behavior often occurs in organizations. For example, it is found that employees in China, America, and Pakistan have a high knowledge hiding rate in the organization.2 Most of the existing research focuses on the analysis of knowledge-sharing behaviors, but recently scholars are calling for more research on knowledge-hiding behaviors.3

Previous studies on antecedents of knowledge hiding have mainly focused on individual characteristics,4–6 interpersonal relationships,7–9 and organizational factors.10 In recent years, scholars have gradually begun to pay attention to the influence of the leader and explored the influencing mechanisms between leader behaviors and employee knowledge hiding. For example, scholars found that abusive supervision can cause employees’ knowledge hiding through psychological contract violation and interpersonal justice,3,11 Altruistic leadership is negatively related to knowledge hiding.12 When employees encounter ethical leaders, increased psychological safety may prompt them to reduce knowledge-hiding behaviors.13 And some scholars have found that ethical leadership weakens knowledge hiding among service industry employees through meaningful work perception.14 In general, most of the existing studies only focus on the positive or negative aspects of leadership styles, and few scholars discuss how a leader’s word-deed misalignment influences employee’s knowledge hiding behaviors. Scholars use the term “leader hypocrisy” to capture the perceptions of a leader’s word-deed misalignment.15,16 For instance, a leader has been promoting a culture of empowerment and risk-tolerant, but he/she still make most decisions and the employees who only “play-safe” get promoted more easily.

Studies show that hypocritical behaviors can help individuals, especially leaders, gain more moral benefits in the first place by misleading others, but those behaviors are likely to bring negative impact and perception to others.17 Due to implicit leadership theory, leaders are often placed on high expectations by followers. When followers perceive the inconsistency between leaders’ words and deeds, their relationship with the leader, as well as identification and positive affect will be harmed, and then result in negative work outcomes. At present, few studies have discussed the influence of leader hypocrisy on employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors and the underlying mediating mechanism. To address this issue, the current study draws on self-determination theory (SDT) to build a theoretical model and investigate the relationships between these concepts.

The purpose of this paper includes three main aspects: First, we try to explore the relationship between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Second, drawing on SDT, we try to explore the meditating mechanism between leader hypocrisy and knowledge hiding. According to SDT, people have three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. We argue that when employees perceive an inconsistency between a leader’s words and behaviors, their basic psychological needs will be harmed, leading to negative behaviors such as knowledge hiding. Third, we consider followers’ interdependent self-construal as a boundary condition, in other words, it moderates the relationship between employees’ basic psychological needs satisfaction and employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. The high interdependent self-construal individuals pay more attention to harmonious interpersonal relationships with others.18–20 They are more likely to maintain good relationship with the team, and therefore are more reactive and helpful to others’ knowledge requests. Thus, we argue that even if employees are not quite unsatisfied with their basic psychological needs because of leader hypocrisy, they may also be willing to share knowledge and information with their colleagues in the workplace.

Our research makes three main contributions: (i) Drawing on SDT, this paper extends our understanding of leader hypocrisy and its influence on employee behaviors such as knowledge hiding, which also enriches the research on the antecedents of knowledge hiding; (ii) this paper explores the mediation mechanism between leader hypocrisy and knowledge hiding behaviors. We specifically chose basic psychological needs satisfaction as a mediator according to SDT, to extend the literature on explaining underlying mechanisms between leader hypocritic behaviors and follower sequent knowledge hiding behaviors; (iii) We extend the leadership and knowledge hiding literature by discussing the moderating effect of follower’s interdependent self-construal, as well as the moderated mediation effect.

The structure of our paper is organized as follows: First, we review the literature and propose our hypotheses, then construct the theoretical model; Secondly, we explain the data collecting process and measures of variables used in our model; Thirdly, we examine the reliability and validity of the data and correlations of variables; Fourthly, we test the mediating effect and moderating effect through hierarchical multiple regression analysis, and test the moderating mediation effect through PROCESS. Fifthly, we discuss the conclusions and implications of our conclusions, and we also indicate the limitations and future directions of our research; Finally, we conclude our findings and reflect on the theoretical and practical implications.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Leader Hypocrisy and Knowledge Hiding

Leader hypocrisy generally refers to the inconsistencies in leaders’ words and deeds.15 In most studies, it is used as a subjective perception of the way leaders behave, and an explanation for the deviation of leaders’ words and deeds.21 Even though some leaders present a positive image in the organization, they could also be regarded as hypocritical because of noticing the conflict between behaviors they later exhibit and the image they have already presented. For example, charismatic leaders have been found to inspire employees to work by establishing strong organizational values, which are initially recognized and admired by employees. But some charismatic leaders may turn out to be inconsistent in their later behaviors with the values they normally advocate, and be perceived as hypocritical by others.22 Scholars found that hypocrisy can cause an individual’s negative emotions.23 In an organization, it could be manifested in employees’ despise, disappointment, and anger towards leaders, which will further reduce employees’ trust in their leaders and lead to employees’ negative work behaviors.16,22

Knowledge hiding refers to the situation in which an employee deliberately conceals or hides the knowledge and information requested by others in the workplace.7 Knowledge hiding usually appears in three forms, which also are the three dimensions of the corresponding construct: playing dumb, evasive hiding, and rationalized hiding.7 Playing dumb refers to the behavior that the “knowledge hider” possesses the knowledge required by others but claims not. Evasive hiding refers to a “knowledge hider” who gives the requester information that is not what they ask for, or promises to give them an answer later, but with no intention of doing so. Rationalized hiding means that the “knowledge hider” implies to the inquirer that he/she cannot tell them for some reason, or simply accuses others.7 Studies have shown that knowledge hiding has many negative effects on individuals and teams. At the individual level, knowledge hiding is negatively related to employees’ creativity and affects employees’ work innovation behavior and thriving at work.10,24–26 At the team level, there is also a negative correlation between knowledge hiding and team viability, and team project performance.27,28

According to the perspective of SDT, people mainly pursue the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The need for autonomy refers to the need that a person can make choices in workplace activities based on self-intention and self-perception; The need for competence refers to an individual’s perception of the validity of his abilities in the workplace environment; The need for relatedness refers to the needs that a person feel trusted and related with others.29 When employees perceive that the leaders’ words and deeds are inconsistent, they may consider their leaders as untrustworthy and lack integrity, thus falling into a distrust spiral with their leaders.30 On the other hand, When employees think their leaders lack integrity, they will perceive less interpersonal justice in the workplace.31 The distrust of the leaders and perceived injustice will hinder the timely communication between the employees and the leaders, thus preventing employees from making full use of the existing resources in the organization. This may cause employees to fail to perform tasks with optimal efficiency, and their autonomy needs and competence needs will be undermined. At the same time, the relationship between employees and leaders is usually weak, and the relatedness needs of employees also cannot be fully met. The weak ties between leader and follower may cause the latter to doubt the effectiveness of the leaders’ management,32 and they may lower their expectations for the organization, their organizational identity may be harmed, and then lead to knowledge hiding behaviors.8 Moreover, when employees perceive unfairness in the workplace, they are also more likely to engage in knowledge hiding in response to a negative leader’s behavior.11 Therefore, we expect that employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy are positively related to their knowledge hiding behaviors.

To sum up, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant positive correlation between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and knowledge hiding.

The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction

According to SDT, the internal motivations of individual behavior are affected by their basic psychological needs. Basic psychological needs refer to the psychological nutrition necessary to maintain people’s psychological growth, integrity, and well-being.33 It is mainly composed of three parts: autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

For the impact of basic psychological needs, studies have shown that leadership styles such as authentic leadership can affect the basic needs of subordinates.34 Thus, contrary to being authentic, we argue that leader hypocrisy can also affect employees’ basic psychological needs. In general, when employees perceive that their leaders’ hypocrisy, all three of their basic psychological needs will be destroyed. According to SDT, the satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs is associated with individual behavioral motivation. Therefore, we expect that employees’ perceptions of their leaders’ hypocrisy will affect their knowledge exchange behaviors.

On the one hand, leader hypocrisy perceptions will reduce the communication frequency between employees and leaders. A lack of timely communication will make employees unable to get timely guidance from leaders, and be forced to use their limited resources and technologies to complete work tasks. Without enough resources and support, it is difficult for employees to work independently, which will diminish employees’ autonomy need satisfaction.

On the other hand, when the leaders’ words and deeds are inconsistent, followers cannot understand the real intention of the leaders, and they may always feel confused. In this situation, employees usually do not know how to behave themselves, and even have a vague cognition of their role in the workplace. The ambiguous work environment can be confusing to employees and reduce their confidence in their competence.35 Employees may not be able to complete work tasks in the best way and with the best efficiency, which will also affect their satisfaction needs for competence.

Considering the need for relatedness, when employees perceive their leaders’ hypocrisy, they may question whether the caring and support shown by leaders are genuine, and tend to believe that leaders are unlikely to truly care about them and their career development, thus jeopardizing the relationships between them as well as the relatedness need of employees.

In summary, due to the limitation of resources, employees’ confusion about expectations and questioning of their leaders’ concern, their autonomy need, competence need and relatedness need can not be met. Employees may reduce expectations for the organization and organizational identity. In this situation, when a colleague requests for knowledge, they may be reluctant to spend extra time and energy on work. The unsatisfied employees are unwilling to act prosocial or proactive, which may further lead to knowledge hiding behaviors. In conclusion, we propose:

Hypothesis 2: Basic psychological needs satisfaction mediates the relationship between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and knowledge hiding. In other words, employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy reduce their satisfaction of basic psychological needs, thereby positively related to employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors.

The Moderating Role of Interdependent Self-Construal

According to Markus and Kitayama,20 individual self-construal includes the content of two dimensions: interdependent self-construal and independent self-construal, and everyone has a bias on a different dimension.36 Scholars have found that self-construal exhibits an important influence on individual behaviors. Studies show that interdependent self-construal moderates the relationship between mindfulness and prosocial behavior.37 Scholars also found that interdependent self-construal moderates the relationship between occupational adaptability on performance is achieved through work-oriented initiatives.38 Different from high independent self-construal employees who may be considered egoistic,39 employees with high interdependent self-construal pay more attention to the sense of connection with others and prefer to get along well with others.20,40 Therefore, in this paper, we specifically focus on interdependent self-construal, as a potential moderator for the relationship between employees’ basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding behaviors.

Employees with high interdependent self-construal tend to pay more attention to group interests. They feel a strong sense of responsibility to members of the group. Even though they perceived the hypocrisy of leaders and their basic psychological needs cannot be fully met, they still believe that members should actively cooperate and make full use of the existing material and knowledge resources to maximize the benefits of the interests of the group. According to Hu et al, individuals with high interdependent self-construal are more likely to show altruistic tendencies.41 Therefore, even if their basic psychological needs are not satisfied, they may try their best to help colleagues when faced with knowledge requests, thus weakening the negative correlation between basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding. To sum up, we propose:

Hypothesis 3a: Interdependent self-construal moderates the negative correlation between employees’ basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding behaviors. In particular, when interdependent self-construal is high, the negative relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding is weaker, and vice versa.

Since the interdependent self-construal moderates the relationship between employees’ basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding, and basic psychological needs satisfaction mediates the relationship between leader hypocrisy perceptions and knowledge hiding. We expect that the interdependent self-construal can moderate the indirect effect between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and knowledge hiding. Because when individual interdependent self-construal is high, their satisfaction of basic psychological needs, especially the need for relatedness will not only depend on leaders but also on colleagues. This may influence the proposed mediation mechanism.

Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 3b: The interdependent self-construal moderates the indirect effect between employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy and their knowledge hiding behaviors through basic psychological needs satisfaction.

According to the assumptions in this paper, the theoretical model is shown in Figure 1 below:

|

Figure 1 Theoretical model. |

Methods

Procedure and Participants

The data were collected from various companies located in major cities in mainland China. To increase the generalizability of our results, the companies included in our survey belong to different industries, such as manufacturing, finance, IT, real estate, and biotechnology. We collaborated with human resources managers or directors of these companies to send out the questionnaires. The HR managers/directors randomly selected the employees of various departments to participate in the survey. The method of on-site distribution and filling of questionnaires was adopted. We explained the academic use of the survey results and the confidentiality of the questionnaire and encouraged employees to fill it out according to their truthful feeling and situation. A total of 499 out of 500 questionnaires distributed were returned. After excluding the invalid samples (e g missing demographic information, too many incomplete items or items with same score, failed with bogus items), a total of 336 valid samples were obtained, yielding an effective response rate of 67%.

The final sample used in this study comprises 58% male and 42% female employees. The average age of employees was 30, with 83% between 24 and 36 years old, 65% had a junior college degree or below, and 35% had a bachelor’s degree or above. And 61% of employees were from joint ventures. In addition, the average tenure of employees was 4 years.

Measures

All the scales used in this paper were adapted from existing research in English, and all the variables were measured on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree, 7= strongly agree. As the empirical study was conducted in a Chinese context, we adopted the “Translation and back-translation procedure” to all the scales used in the questionnaires following previous suggestions on cross-cultural use of scales.42

Perceptions of Leader Hypocrisy (PLH)

Employee’s perception of leader hypocrisy was measured with the scale from Dineen et al43 which included four items, sample items such as “My supervisor tells us to follow the rules but don’t follow them him/herself”, “My supervisor asks me to do things he or she won’t do himself or herself”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient value is 0.895.

Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction (BPN)

We measured this variable using the nine-item scale from Sheldon et al.44 The scale includes three dimensions of needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The sample item of the needs for autonomy dimension was “I feel that my choices are based on my true interests and values”. The sample item of the needs for competence dimension was “I feel that I am successfully completing difficult tasks and projects”. The sample item of the needs for relatedness dimension was “I feel a strong sense of intimacy with the people I spend time with”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient value is 0.942.

Interdependent Self-Construal (ISC)

Employee’s interdependent self-construal was measured using Qi et al’s adjusted four-item scale. Singelis developed a self-construal scale in 1994, which had a total of 24 items, including 12 items of interdependent self-construal and 12 items of independent self-construal.45 Later, Qi et al simplified the scale and demonstrated its applicability in the Chinese context.46 There were seven items on the scale of Qi, including four items of interdependent self-construal and three items of independent self-construal. In this paper, four items adapted by Qi et al were used to measure employees’ interdependent self-construal. Sample items such as “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of the group I am in”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient value is 0.848.

Knowledge Hiding (KH)

We used the twelve-item scale developed by Connelly et al to measure knowledge hiding.7 The scale measured three dimensions of knowledge hiding: playing dumb, evasive hiding, and rationalized hiding. The sample item of playing dumb dimension was “When a colleague asks me for knowledge, I pretend that I do not know the information”. The sample item of evasive hiding dimension was “When a colleague asks me for knowledge, I agree to help him/her but instead gave him/her information different from what he/she wanted”. The sample item of rationalized hiding dimension was “When a colleague asks me for knowledge, I explain that the information is confidential and only available to people on a particular project”. The Cronbach’s α coefficient value is 0.966.

Control Variables

The demographic variables such as gender, age, education, enterprise nature, and tenure were controlled in the analysis following previous studies in this field.8

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

We used AMOS 26.0 to conduct the confirmatory factor analysis on the constructed model, and the test results were shown in the following table As can be seen from Table 1, the one factor model results: X2 = 3636.571, df = 377, X2/df = 9.646, NFI = 0.606, CFI = 0.630, RMSEA = 0.161; the two factor model results: X2 =1941.218, df = 376, X2/df = 5.163, NFI = 0.789, CFI = 0.822, RMSEA = 0.111; The three-factor model results: X2 = 1654.561, df = 374, X2/df = 4.424, NFI = 0.821, CFI = 0.855, RMSEA = 0.101.The four-factor model results: X2 = 939.364, df = 371, X2/df = 2.532, NFI = 0.898, CFI = 0.936, RMSEA = 0.068. It suggests that the four-factor model has the best fitting result, and the fitting indexes are better than other alternative models, indicating a decent validity and availability for further analysis. The results also show that the fitting indexes of the one-factor model are significantly worse than the four-factor model, suggesting that there is no serious common method variance in our data.

|

Table 1 Comparison of Measurement Models |

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

We used SPSS 25.0 to carry on the correlation analysis and used the Pearson Correlation Coefficient to carry on the test. The results were shown in Table 2:

|

Table 2 Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations |

According to Table 2, there is a significant negative correlation between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and basic psychological needs satisfaction (b = −0.427, p < 0.01). Perceptions of leader hypocrisy are positively related to knowledge hiding (b = 0.563, p < 0.01). And employees’ basic psychological needs satisfaction is negatively correlated with their knowledge hiding behaviors (b = −0.480, p < 0.01). Besides, there is a significant negative correlation between interdependent self-construal and knowledge hiding (b = −0.389, p < 0.01).

Hypothesis Testing

Mediating Effect Tests

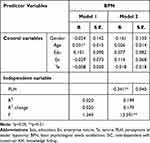

In this paper, we used the hierarchical multiple regression analysis to test the mediation effect and the moderating effect of the model, and then adopted the bootstrapping and regression method developed by Hayes to provide further analysis.47 The results were shown in Tables 3 and 4

|

Table 3 Regression Results of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction |

|

Table 4 Regression Results of Knowledge Hiding |

Model 1 was used as a baseline regression to control for gender, age, education, enterprise nature, and tenure with basic psychological needs satisfaction as dependent variables. Based on model 1, perceptions of leader hypocrisy are added into the regression equation to obtain model 2. Then in model 3, knowledge hiding was set as the dependent variable and controlling gender, age, education, enterprise nature, and tenure. The perceptions of leader hypocrisy were added to the regression equation to get model 4. In model 5, the basic psychological needs satisfaction was added to the regression model as the mediator. The moderator interdependent self-construal was added to the regression equation to obtain model 6. In model 7, the basic psychological needs satisfaction, and interdependent self-construal were centralized, and their interaction term was calculated and added to the regression model.

According to model 2, there is a significant negative correlation between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and basic psychological needs satisfaction (b = −0.341, p < 0.01). As can be seen from model 4, perceptions of leader hypocrisy are positively related to employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors (b = 0.490, p < 0.01), indicating that there is a significant direct effect between the employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy and their knowledge hiding behaviors. Hypothesis 1 is supported. According to model 5, when the basic psychological needs satisfaction is added as the mediation variable, perceptions of leader hypocrisy are still significantly positive related to knowledge hiding (b = 0.372, p < 0.01), and there is a significant negative correlation between basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding (b = −0.345, p < 0.01). According to the conditions of mediating effects,48 the influence factor between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and knowledge hiding behaviors changes from b = 0.490 to b = 0.372 after the mediation variable of basic psychological needs satisfaction is added, indicating that basic psychological needs satisfaction plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Hypothesis 2 is likely to be supported, further evidence is provided using the analysis suggested by Hayes.47

Moderating Effect Tests

In model 6, the interdependent self-construal is negatively related to knowledge hiding (b = −0.135, p < 0.05). According to model 7, the interaction item of basic psychological needs satisfaction and interdependent self-construal is positively related to knowledge hiding (b = 0.134, p < 0.01). The simple slope analysis result of moderating effect is shown in Figure 2:

|

Figure 2 The moderating effect of interdependent self-construal on basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding. |

As can be seen from Figure 2, compared with employees with low interdependent self-construal, employees with high interdependent self-construal have a weaker negative correlation between basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding (the slope is more gentle). In other words, the interdependent self-construal attenuates the negative correlation between employees’ basic psychological needs satisfaction and their knowledge hiding behaviors. Thus, Hypothesis 3a is supported.

Moderating Mediation Effect Tests

To further test our hypothesis, we adopted the PROCESS macro of SPSS and followed Hayes’ suggestion on testing relevant effects.47 A bootstrapping sample was set at 5000 times and the significance of the effect we tested was computed based on 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. To further verify the existence of mediating effect, we adopted Hayes’ approach to run the 4th model in PROCESS macro. The results show that there is a significant mediation effect. (b =0.118, [0.056, 0.210]). Therefore, we believe that basic psychological needs satisfaction plays an intermediary role between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Thus, hypothesis 2 is supported. And the results of moderating mediation effects were shown in Table 5:

|

Table 5 Conditional Indirect Effects of Perceptions of Leader Hypocrisy on Knowledge Hiding via Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction |

According to Table 5, when employees’ interdependent self-construal is low(-SD), since b = 0.129, [0.063, 0.221], 95% confidence interval does not include 0, indicating that employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy have a significant positive impact on their knowledge hiding behaviors through basic psychological needs satisfaction. When employees have a high level of interdependent self-construal(+SD), b = 0.014, [−0.069, 0.136], at this point, employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy have no significant influence on their knowledge hiding behaviors through the basic psychological needs satisfaction. In other words, when interdependent self-construal is low, the indirect effect of employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy and their knowledge hiding behaviors through basic psychological needs satisfaction is significant, and such indirect effect is non-significant when interdependent self-construal is high. Thus, hypothesis 3b is supported.

Discussions

This paper aims to explore the relationship between leader hypocrisy and employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors, as well as the underlying mediation and moderation mechanisms. Through theoretical model building and empirical examination, the following conclusions are obtained:

First, leader hypocrisy can significantly impact knowledge-hiding behaviors. When employees find that the leaders’ words and deeds are inconsistent, they may be disappointed with the leader, have a sense of mistrust and unfairness, and then reduce their sense of organizational identity. These are all the proximal factors to influence employees’ basic psychological needs. While employees’ basic psychological needs are unsatisfied, negative responses may be triggered. The shift attack perspective can also provide support for our conclusion.11 Since leaders usually control the critical resources such as employees’ salary and promotion opportunities, employees will not easily express their dissatisfaction with their leaders,11 but they may take the method of shifting the attack, venting this negative emotion on colleagues. So, when colleagues make knowledge requests, they will respond in a negative way such as knowledge hiding.

Second, basic psychological needs satisfaction plays a mediating role between employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy and their knowledge hiding behaviors. From the perspective of SDT, the satisfaction of people’s autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs are associated with positive work behaviors.49 Perceptions of leader hypocrisy make employees confused, uncertain, and unconfident about their working environment, unable to allocate resources optimally, and alienated from leaders. These will jeopardize the satisfaction of employees’ basic psychological needs, thereby reducing their enthusiasm for work, making employees unwilling to spend extra time and energy dealing with work problems, and eventually unwilling to respond to colleagues’ knowledge requests.

Third, interdependent self-construal alleviates the negative correlation between employees’ basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding behaviors. Individuals with high interdependent self-construal are more inclined to construct harmonious relationships with others.20 And therefore they are more likely to get along well with colleagues, interact positively, and help each other. Even if their basic psychological needs cannot be met, they might also respond to their colleagues’ knowledge requests. Also, individuals with high interdependent self-construal seek the satisfaction of their needs from different social relationships, and that may mitigate the negative impact of leader hypocrisy on basic psychological needs, in other words, diminish the mediating effect of basic psychological needs satisfaction on the relationship between leader hypocrisy and knowledge hiding behaviors.

Implications

Theoretical Implications

The theoretical implications of this paper comprise the following three aspects. First, there is abundant research on knowledge sharing, but relatively insufficient attention has been paid to knowledge hiding. Many scholars have tried to promote knowledge exchange and cooperation among employees by looking for ways to increase knowledge sharing, but some scholars have found that methods of increasing knowledge sharing are less effective in reducing employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors, and knowledge hiding are still here and there.3 Therefore, this paper directly explores the antecedents of knowledge hiding and studies how leader hypocrisy causes subsequent knowledge hiding behaviors. In addition, the interdependent self-construal is discussed as a boundary condition, expanding the knowledge hiding research literature.

Second, at present, relevant researches on the concept of leader hypocrisy are also hard to find. As stated by Ilsev and Aydin, scholars have not paid enough attention to the variable of leader hypocrisy, and there is a large space for the study of its consequences.30 This paper responds to the scholarly call and explores the changes in employees’ basic psychological needs satisfaction and the resulting knowledge hiding behaviors after they perceive their leaders’ hypocrisy.

Finally, since Connelly et al put forward the concept of knowledge hiding,7 scholars’ research on knowledge hiding mainly constructs models from the perspectives of social exchange theory, conservation of resource theory, social cognitive theory, and psychological ownership theory. This paper provides an alternative perspective from self-determination theory to investigate the black box between leader hypocrisy and knowledge-hiding behavior. According to Deci and Ryan,33 when people’s three basic psychological needs are satisfied, the intrinsic motivation of individuals can be driven, which in turn affects individual behaviors. This paper adopts the framework of self-determination theory to construct the model and selects basic psychological needs satisfaction as the mediating variable, which expands the application of SDT in knowledge hiding research.

Practical Implications

The practical implications of this paper are mainly divided into three aspects. First, leaders’ leadership style, words, and deeds will subtly affect employees’ work behaviors. Scholars have found that abusive supervision, altruistic leadership, ethical leadership, and transformational leadership all have an impact on employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors.3,11–14,50 Leaders’ long-term inconsistency in words and deeds will also give employees a wrong signal that their organizational atmosphere is full of dishonesty. This will lead to a sense of distrust in colleagues, and they may be unwilling to share their knowledge and experience with colleagues. But the sustainable competitive advantage of an organization depends on the effective use of existing knowledge to promote the creation of new knowledge.51 Therefore, it is of significance to explore the relationship between employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy and knowledge-hiding behaviors. This will help enterprises attach importance to the consistency of leaders’ words and deeds, restrain leaders’ behaviors, and create an honest team atmosphere for employees. In this way, employees’ psychological safety will also be increased, which will help reduce knowledge hiding behaviors,13 and facilitate the development and innovation of the organization.

Second, according to the research conclusions of this paper, when the basic psychological needs of employees are not satisfied, knowledge hiding behaviors are more likely to occur. Therefore, enterprises need to attach more importance to the satisfaction of employees’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs. Enterprises can implement a rotation system, so that employees can feel the difference among different positions, and then choose the positions they are interested in and suitable for themselves. According to Trepanier et al,52 the unsatisfied need for autonomy is often accompanied by the emotional exhaustion of employees. So, when employees’ autonomy need is met, they will also have a good working mood, thereby increasing their work enthusiasm. Appropriately assign some challenging but effortless tasks to employees. On the one hand, it can exercise employees’ ability. On the other hand, it can also satisfy the employees’ sense of achievement. In terms of meeting relatedness needs, multiple intra-team and inter-team activities can be organized to make employees feel that the team is a whole. Leaders can also organize regular conversations with employees, give employees some work feedback, praise the good parts completed by employees, and gently point out their deficiencies. At the same time, understand the problems encountered by employees in their work and discuss solutions with them. When the three basic psychological needs of employees are satisfied, they will actively cooperate to complete the work and reduce knowledge-hiding behaviors.

Third, since employees with high interdependent self-construal are more likely to reduce knowledge hiding behaviors, enterprises can appropriately assign some tasks related to each other to cultivate their sense of teamwork and shorten the psychological distance among employees. Let employees realize that mutual assistance can significantly improve work efficiency, and strengthen team-building activities to promote communication and cooperation among employees. Moreover, the organization needs to pay attention to selecting the right people to possess critical knowledge and to lead knowledge sharing, people with high interdependent self-construal may be more comfortable with cooperating and sharing.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

There are still some limitations in our work. Since the variables used in our model are all individual self-rated, the results are subjective to some extent. The problem of common method variance cannot be completely solved.53 Although confirmatory factor analysis results show that our results are not much affected by common method variance, we can still consider using multi-timeframe and multi-sources data in future studies.

Besides, in this paper, the mediating variable only focuses on the impact of basic psychological needs satisfaction, while the perceptions of leader hypocrisy may also bring other effects on employees’ emotions and cognition. According to Laurent et al,23 people’s perceptions of leader hypocrisy will lead to negative emotions such as anger and disgust. It is also proved that employees’ perception of leader hypocrisy would cause feelings of disappointment and anger.22 These negative emotions will consume employees’ emotional resources. And leaders’ hypocrisy can also make employees question the fairness of the organization.31 Therefore, future research can consider whether emotional exhaustion and organizational justice play mediating roles between perceptions of leader hypocrisy and knowledge hiding.

In addition, according to Connelly et al,7 knowledge hiding can be divided into three dimensions: playing dumb, evasive hiding, and rationalized hiding. In this study, we only use an aggregated variable of knowledge hiding. In future studies, scholars can consider exploring the different effects of perceptions of leader hypocrisy on employees’ three kinds of knowledge hiding behaviors. What’s more, some scholars believe that knowledge categories can also affect individual knowledge hiding behaviors. For example, it is found that the influence of personal competitiveness on scholars’ explicit and implicit evasive knowledge hiding behavior is different.54 In the future, it can also be considered to explore the difference between explicit and implicit knowledge in knowledge hiding behaviors caused by employees’ perceptions of leader hypocrisy.

Finally, this paper only considers the moderating effect of interdependent self-construal, and future studies could explore different boundary conditions. According to previous studies, employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors are also affected by individual performance-proven goal orientation and task interdependence.6,54,55 To complete work tasks more efficiently, individuals with a high-performance goal orientation or a high degree of interdependence with others’ tasks may be willing to share their experience within a team and cooperate to achieve a win-win result, even if they find that their leaders are inconsistent in their words and deeds. In the future, they can also be considered as boundary conditions.

Conclusions

This paper explores the influence of leader hypocrisy on employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors and its possible mediating mechanism. The results show that the perceptions of leader hypocrisy are positively related to employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors, and basic psychological needs satisfaction partially mediates the relationship. In addition, the interdependent self-construal moderates the negative correlation between basic psychological needs satisfaction and knowledge hiding. We expect that our findings can help companies take steps to reduce employees’ knowledge-hiding behaviors.

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Experimentation of Wuhan Textile University and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Before the survey, the written informed consent form, and an introduction of the purpose of our survey research were provided to all participants together with the questionnaires. Explanations were made to the participators that this research adopts the principle of voluntary participation, and all the collected data would be kept strictly confidential, and the survey is only for research purposes so no individual or organization can access the data except our researchers. Before filling out the survey questionnaires, all participants claimed that they understand the purpose of our survey research and agree to participate voluntarily.

Acknowledgments

All authors would like to gratitude the research fellows who participated in the data collection and analysis of the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the 11th batch of key project “Machine learning Embedded SFC Model Research” of Hubei Provincial Humanities Key Research Base - Enterprise Decision Support Research Center; This study was also supported in part by the Young Scientists Funds of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education of China under Grant 19YJC630236; in part by the Philosophy and social science research project of Hubei Provincial Department of Education under Grant 19Q093; in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 71702066; in part by the National Social Science Foundation of China under Grant 17BGL230; and in part by the Institute of Distribution Research, Dongbei University of Finance and Economics under Grant IDR2021YB004;.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Muhammed S, Zaim H. Peer knowledge sharing and organizational performance: the role of leadership support and knowledge management success. J Knowl Manag. 2020;24(10):2455–2489. doi:10.1108/JKM-03-2020-0227

2. Arain GA, Bhatti ZA, Hameed I, Fang YH. Top-down knowledge hiding and innovative work behavior (IWB): a three-way moderated-mediation analysis of self-efficacy and local/foreign status. J Knowl Manag. 2019;24(2):127–149. doi:10.1108/JKM-11-2018-0687

3. Pradhan S, Srivastava A, Mishra DK. Abusive supervision and knowledge hiding: the mediating role of psychological contract violation and supervisor directed aggression. J Knowl Manag. 2020;24(2):216–234. doi:10.1108/JKM-05-2019-0248

4. Pan W, Zhang Q, Teo TS, Lim VK. The dark triad and knowledge hiding. Int J Inf Manage. 2018;42:36–48. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.05.008

5. Wu J. Impact of personality traits on knowledge hiding: a comparative study on technology-based online and physical education. Front Psychol. 2021;12:791202. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.791202

6. Zhu Y, Chen T, Wang M, Jin Y, Wang Y. Rivals or allies: how performance-prove goal orientation influences knowledge hiding. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(7):849–868. doi:10.1002/job.2372

7. Connelly CE, Zweig D, Webster J, Trougakos JP. Knowledge hiding in organizations. J Organ Behav. 2012;33(1):64–88. doi:10.1002/job.737

8. Yao Z, Zhang X, Luo J, Huang H. Offense is the best defense: the impact of workplace bullying on knowledge hiding. J Knowl Manag. 2020;24(3):675–695. doi:10.1108/JKM-12-2019-0755

9. Zhao H, Xia Q, He P, Sheard G, Wan P. Workplace ostracism and knowledge hiding in service organizations. Int J Hosp Manag. 2016;59:84–94. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.09.009

10. Malik OF, Shahzad A, Raziq MM, Khan MM, Yusaf S, Khan A. Perceptions of organizational politics, knowledge hiding, and employee creativity: the moderating role of professional commitment. Pers Individ Dif. 2019;142(1):232–237. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.005

11. Khalid M, Bashir S, Khan AK, Abbas N. When and how abusive supervision leads to knowledge hiding behaviors: an Islamic work ethics perspective. Leader Organiz Dev J. 2018;39(6):794–806. doi:10.1108/LODJ-05-2017-0140

12. Abdillah MR, Wu W, Anita R. Can altruistic leadership prevent knowledge-hiding behaviour? Testing dual mediation mechanisms. Knowledge Manage ResPract. 2020;2020:1–15.

13. Men C, Fong PS, Huo W, Zhong J, Jia R, Luo J. Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: a moderated mediation model of psychological safety and mastery climate. J Bus Ethics. 2020;166(3):461–472.

14. Anser MK, Ali M, Usman M, Rana MLT, Yousaf Z. Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: an intervening and interactional analysis. Serv Ind J. 2021;41(5–6):307–329. doi:10.1080/02642069.2020.1739657

15. Brunsson N. The Organization of Hypocrisy: Talk, Decisions, and Actions in Organizations. Adler N. UK: Wiley; 1989.

16. Greenbaum RL, Mawritz MB, Piccolo RF. When leaders fail to “walk the talk”: supervisor undermining and perceptions of leader hypocrisy. J Manage. 2015;41(3):929–956. doi:10.1177/0149206312442386

17. O’ Connor K, Effron DA, Lucas BJ. Moral cleansing as hypocrisy: when private acts of charity make you feel better than you deserve. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2020;119(3):540–559. doi:10.1037/pspa0000195

18. Kwan VS, Bond MH, Singelis TM. Pancultural explanations for life satisfaction: adding relationship harmony to self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(5):1038–1051. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1038

19. Oishi S, Diener E. Goals, culture, and subjective well-being. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2001;27(12):1674–1682. doi:10.1177/01461672012712010

20. Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98(2):224–253. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

21. Effron DA, O’Connor K, Leroy H, Lucas BJ. From inconsistency to hypocrisy: when does “saying one thing but doing another” invite condemnation? Res Organ Behav. 2018;38:61–75. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2018.10.003

22. Cha SE, Edmondson AC. When values backfire: leadership, attribution: and disenchantment in a values-driven organization. Leadersh Q. 2006;17(1):57–78. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.10.006

23. Laurent SM, Clark BA, Walker S, Wiseman KD. Punishing hypocrisy: the roles of hypocrisy and moral emotions in deciding culpability and punishment of criminal and civil moral transgressors. Cogn Emot. 2014;28(1):59–83. doi:10.1080/02699931.2013.801339

24. Jahanzeb S, Fatima T, Bouckenooghe D, Bashir F. The knowledge hiding link: a moderated mediation model of how abusive supervision affects employee creativity. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2019;28(6):810–819. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2019.1659245

25. Černe M, Hernaus T, Dysvik A, Škerlavaj M. The role of multilevel synergistic interplay among team mastery climate, knowledge hiding, and job characteristics in stimulating innovative work behavior. Hum Resour Manag J. 2017;27(2):281–299. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12132

26. Jiang Z, Hu X, Wang Z, Jiang X. Knowledge hiding as a barrier to thriving: the mediating role of psychological safety and moderating role of organizational cynicism. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(7):800–818. doi:10.1002/job.2358

27. Wang Y, Han MS, Xiang D, Hampson DP. The double-edged effects of perceived knowledge hiding: empirical evidence from the sales context. J Knowl Manag. 2019;23(2):279–296. doi:10.1108/JKM-04-2018-0245

28. Zhang Z, Min M. The negative consequences of knowledge hiding in NPD project teams: the roles of project work attributes. Int J Project Manage. 2019;37(2):225–238. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.01.006

29. Brenning K, Soenens B. A self-determination theory perspective on postpartum depressive symptoms and early parenting behaviors. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73(12):1729–1743. doi:10.1002/jclp.22480

30. Ilsev A, Aydin EM. Leader Hypocrisy and Its Emotional, Attitudinal, and Behavioral Consequences. In: SELİN MC, Özge TE, editors. Destructive Leadership and Management Hypocrisy. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2021:162–174.

31. Simons T, Friedman R, Liu LA, Parks JM. Racial differences in sensitivity to behavioral integrity: attitudinal consequences, in-group effects, and “trickle down” among Black and non-Black employees. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(3):650–665. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.650

32. Moorman RH, Darnold TC, Priesemuth M. Perceived leader integrity: supporting the construct validity and utility of a multi-dimensional measure in two samples. Leadersh Q. 2013;24(3):427–444. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.02.003

33. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11(4):227–268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

34. Leroy H, Anseel F, Gardner WL, Sels L. Authentic leadership, authentic followership, basic need satisfaction, and work role performance: a cross-level study. J Manage. 2015;41(6):1677–1697. doi:10.1177/0149206312457822

35. Liu L, Jia Y. Guanxi HRM and employee well-being in China. Employee Relation. 2021;43(4):892–910. doi:10.1108/ER-09-2019-0379

36. Yang H, van Rijn MB, Sanders K. Perceived organizational support and knowledge sharing: employees’ self-construal matters. Int J Hum Resour Manage. 2020;31(17):2217–2237. doi:10.1080/09585192.2018.1443956

37. Poulin MJ, Ministero LM, Gabriel S, Morrison CD, Naidu E. Minding your own business? Mindfulness decreases prosocial behavior for people with independent self-construals. Psychol Sci. 2021;32(11):1699–1708. doi:10.1177/09567976211015184

38. Bi Y, Zhang J, Nie Q, Wang M. Do adaptable employees always display high performance? Dual roles of proactive behavior and self-construal. Soc Behav Personal. 2021;49(8):1–16. doi:10.2224/sbp.10464

39. Arnocky S, Stroink M, DeCicco T. Self-construal predicts environmental concern, cooperation, and conservation. J Environ Psychol. 2007;27(4):255–264. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.06.005

40. Chang C. Self-construal and Facebook activities: exploring differences in social interaction orientation. Comput Human Behav. 2015;53:91–101. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.049

41. Hu M, Zhang M, Luo N. Understanding participation on video sharing communities: the role of self-construal and community interactivity. Comput Human Behav. 2016;62:105–115. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.077

42. Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Lonner WJ, Berry JW, editors. Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. Sage Publications, Inc; 1986:137–164.

43. Dineen BR, Lewicki RJ, Tomlinson EC. Supervisory guidance and behavioral integrity: relationships with employee citizenship and deviant behavior. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(3):622–635. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.622

44. Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ, Kim Y, Kasser T. What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80(2):325–339. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.325

45. Singelis TM. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1994;20(5):580–591. doi:10.1177/0146167294205014

46. Qi JY, Qu QX, Zhou YP. How does customer self-construal moderate CRM value creation chain? Electron Commer Res Appl. 2014;13(5):295–304. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2014.06.003

47. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Publications; 2017.

48. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

49. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-Determination Theory. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2017.

50. Ladan S, Nordin NB, Belal HM. Does knowledge based psychological ownership matter? Transformational leadership and knowledge hiding: a proposed framework. J Business Retail Manage Res. 2017;11(4):60–67. doi:10.24052/JBRMR/V11IS04/DKBPOMTLAKHAPF

51. Alavi M, Leidner DE. Review: knowledge management and knowledge management systems: conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterl. 2001;25(1):107–136. doi:10.2307/3250961

52. Trepanier SG, Fernet C, Austin S. Workplace bullying and psychological health at work: the mediating role of satisfaction of needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness. Work Stress. 2013;27(2):123–140. doi:10.1080/02678373.2013.782158

53. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

54. Hernaus T, Cerne M, Connelly C, Vokic NP, Škerlavaj M. Evasive knowledge hiding in academia: when competitive individuals are asked to collaborate. J Knowl Manag. 2019;23(4):597–618. doi:10.1108/JKM-11-2017-0531

55. Huo W, Cai Z, Luo J, Men C, Jia R. Antecedents and intervention mechanisms: a multi-level study of R&D team’s knowledge hiding behavior. J Knowl Manag. 2016;20(5):880–897. doi:10.1108/JKM-11-2015-0451

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.